Get an overview of simple wood, aluminum, and John boats. Learn about their features, benefits, and ideal uses. Perfect for boating enthusiasts looking to choose the right boat for fishing, leisure, or other activities.

When our country was younger, people in widely separated areas developed a number of specialized and distinctive small boats to suit local requirements.

The Ugly Duckling

Everyone knows of the New England dory, and most outdoorsmen have at least heard of the Barnegat Bay sneakbox. Then there was the Adirondack guide boat, the Chesapeake Bay sharpie, the Louisiana pirogue, the Ozarks john boat and a whole catalog of others.

Of them all, about the only one to be in common and practical use today is the john boat. In fact, it is beginning to be evident that this homely design is rapidly becoming a nationally-distributed, all-purpose, low-cost type.

Maybe you have read nothing elsewhere about any such trend and wonder if the above statement is on the level. Sure it is – just take a look around you. At sporting goods and department stores, at roadside marine emporiums and discount houses all over the place you will see john boats stacked like nested dories, waiting to be taken home by the boating public.

The more you look around, the more apparent it becomes that the john boat is pushing aside the familiar plywood pram as an all-purpose economy boat – the sort of boat people use for puttering around on small bodies of water, for getting back and forth around the waterfront, for the kids to play with and so on. And this may be a good thing, for the pram was being used for a lot of purposes for which it was neither intended nor suited and as a result caused everything from dissatisfaction to serious trouble.

In case you’re uncertain as to what a john boat is, well, it might be described as a waterborne mortar bed fitted with thwarts! Kidding aside, it is a type of fishing boat native to the rivers of the Ozarks region of the lower midwest. I don’t know how it came to be called a “john boat” but then, neither are the foremost authorities on small boat history completely sure of how the dory got its name! I can affirm, though, that the john boat was developed specifically for “float trips” on the rivers that meander out of the Ozarks.

In a float trip, the fishing party launches the boat someplace upstream, loads fishing, eating and camping gear aboard, and drifts leisurely downstream with the current in search of likely looking spots. Most of the work is done by the river current, so no real amount of thought ever had to be given to rowing qualities. You might camp out on the riverbank for a night or two, or you could get ambitious and make a whole week’s trip out of it. Then, by prearrangement, there’d be somebody waiting at some downstream town to pick you up and take you home. It got to be quite a thing, with guide services and all that.

The requirement of low cost led to a boxlike shape – no fancy bends or bevels that would give a workman with no seafaring blood in his vein a bad time. This boxlike shape resulted in a square stern, so quite without realizing it the men who developed the type assured that it would have a very long life. When the outboard motor came along, it was a simple matter to pop one in place and use it to shove the boat downstream past unproductive stretches of water. The square stern wasn’t found on most of the specialized boats mentioned at the beginning of this article, for they were meant to be propelled by oars and were given easily-driven hull shapes tending toward pointed sterns. It was hard to put an outboard on them, and when outboards came to be standard equipment they went the way of the farm horse.

Originally, john boats were made from two long side boards which formed the sides, with cross planking on the bottom. When plywood came along it was a natural for the bottoms. After World War II, firms in the lower midwest who were getting into the aluminum boat business started making john boats of this material in addition to runabouts of more boatlike shape.

Early purchasers of the new aluminum john boats were impressed with the combination of noticeable lightness, durability and moderate price. Factories began to send john boats to retail outlets farther and farther from the Ozarks. All of a sudden they are everywhere!

Now, I am absolutely and positively not boosting john boats as being a coming thing in fishing boats for use on the open ocean. That they are not. But, they can reasonably and legitimately be considered as being often rather better for the kind of jobs that plywood prams have been doing (or trying to do) for the last 20 years. They are light and handy, able to carry good loads, cheap yet durable and safe for sheltered waters when used with some sense. As they have buoyancy material under their seats, they won’t sink to the bottom if they do fill with water. Oh, very definitely, they won’t do things some other aluminum boats will do for the salt water sportsman – but they are worth a look on the part of those who are not looking for rough water ability but rather for low cost and high utility.

As soon as a man moves up to a larger boat – by which is meant anything bigger than what he started out with – he discovers that for all its merits, his new and larger boat won’t do some things a little one will. The realization comes that now he needs a second boat. Something small and handy that can be moved around by car, that can be towed or carried by the larger boat … and that costs so little that he can swing it without pain, in spite of the monthly payments on the big boat.

Thirty or 40 years ago, a common waterfront sight was the dinghy, which name is derived from dingi, a small East Indian boat. Such boats were made with traditional steamed oak ribs and planked carvel or lapstrake like any other wooden boat. Some were made of canvas covered canoe style construction. They ranged in size from as small as six feet to around ten feet. Many of them were frankly designed to fit into some particular place on the deck or cabin roof of a yacht, which explains why some as short as six feet were built.

Then along came plywood, the most common stock size of which is four by eight feet. This led to the design and construction of countless thousands of “prams,” a vee-bottom dinghy type that is understood to have originated in the Low Countries of Europe. Their length of just under eight feet was determined by the length of the plywood material from which they were made, not by any operational or functional circumstances.

The result was a cheap and hence widely-used boat. Twenty years ago, the boating magazines were full of advertisements for prams in kit and completed form, and you still see them, often in unpainted form, leaning against buildings and trees at all kinds of retail places. In spite of their commonness, I can’t bring myself to say they were well-thought-out boats with which a man could be happy.

The typical eight foot pram has a central thwart or seat and two more squeezed in far forward and far aft. It can be rowed only from the central thwart. With one man aboard and sitting amidships, balance is good and all is well, but trouble comes when it is desired to carry two persons. The second man has to sit either in the bow or in the stern, where his weight puts the short hull very much out of trim. There is a rocker in a typical pram’s bottom, put there to minimize as much as possible the drag of a very short and wide hull when being rowed, and to permit it to readily pivot to the oars when being used in crowded quarters. This puts most of the working volume under the middle seat, rather little under the end seats, and out of trim she goes!

If the passenger has selected the stern seat, which is usual, he has to straighten his legs and shove his feet under the center thwart to drop his knees far enough so the oarsman’s hands don’t bump them on every recovery. When three are aboard, the forward man has to spread his knees and lean forward so the oarsman has enough room to lean forward on each stroke. Sometimes it’s so darned cramped that the oarsman gives up on trying to do long, strong strokes and rows with short arm motion only, his body bolt upright. This is no way to put drive into a hardpulling hull. And with three aboard, hull volume is hardly adequate for the approximately 450 or 500 pounds that three men will weigh.

When a small outboard motor is put onto the craft, there are problems too. The stern seat is so close to the transom that the operator is practically sitting on top of the motor. Balance is terrible and comfort poor. Only when a second person sits in the bow and holds it down are things reasonably happy. When a third man plunks onto the amidships thwart, the motor’s weight is added to the human overload. With an outboard to do the work there is a temptation to set out on jaunts more ambitious than the dock-to-yacht jaunts for which the craft was originally intended. On such journeys, there is more likelihood of encountering rough water.

The pram was sired by the yacht tender, which of necessity had to be small to fit somewhere aboard a larger craft regardless of the disadvantages brought about by the small size. Its size became standardized in people’s minds through being made in vast numbers from eight-foot plywood. Its cheapness enabled it to be sold widely, often to landlubbers with a hankering to go to sea on a shoestring budget. Its size was copied by many small fiberglass outfits whose managers had no real on-the-water-under-all-conditions boating experience. Its commonness led it to be used for all kinds of purposes for which its parent was never in¬ tended. Prams have been death traps for hundreds of people.

If only the thing were a couple of feet longer, the occupants would be far enough apart for comfort and convenience, and the extra two feet would add enough volume so the craft would have a reasonable chance of coping with the weight of three persons. Or if there were two, the forward part of the hull would be long enough to keep from going down under the weight of a passenger on the thwart ahead of the oarsman.

Also, if one starts with a roll of adequate width, the bottom and sides can all be made from a single piece. Start with a sheet of the desired length, put stiffening grooves in it, bend up the sides, cut two gores in one end to allow for turning up the bow and bending in of the sides to form the bow, weld those seams and the transom – and there you have it! The typical john boat has a minimum number of riveted seams, which saves on labor cost and adds to leak resistance. John boats sell for prices so low they startle you once you look into the matter and this simplicity of manufacture is an underlying reason. A john boat can be compared in simplicity to a small boy’s paper dart – start with a flat sheet, fold it just so, and there is your craft!

While the builder is not limited in length, he is limited by the width of rolls of aluminum sheet. To make a one-piece john boat, so many inches of a sheet’s width will be allotted to the bottom, so many inches to the stiffening grooves, and what is left will make the sides. Small john boats tend to be on the moderately narrow side, and when you go up in length from ten to 16 feet, you often find that beam remains constant. This isn’t bad, it’s just worth knowing. There are other boats that are more stable than john boats, which is simply to say that when in one, you have to remember you’re in a boat. But they are quite stable enough for safety.

A safety imparted by this tendency to narrowness when compared to some other boats is that they propel easily. This past summer I have enjoyed using a 14 foot john boat having a gunwale width of 46 inches. We put a four-horsepower single-cylinder outboard motor on it, this being a light economy motor in keeping with the character of the boat. It was no speedster, but we were rather surprised at how smartly it could clip along even with three aboard. It ran smooth and clean, no fuss or struggle. Not bad at all for an investment totalling under $350 ready to go.

The completely flat bottoms of john boats are tops for producing lift, and with enough power any john boat will plane, and plane easily, on moderate power. When a single person is aboard they tend to plane well up on the surface, with a lot of the hull up forward out of the water and easily pushed aside by wind. When going slow with much weight in the stern, they tend to plow along nose-up. But with a pair of fishing buddies aboard trim is all right and reasonable speed can be achieved safely. Mainly, john boats are not big-power craft. In the smaller ones you are apt to find figures like five and 7 1/2 horsepower on the motor capacity plates; in middle-sized ones the figure may be something like 10 or 12 horsepower, and big ones may be rated to take 18 or 20 or sometimes 30 horsepower.

While it is true that many of the low-prices models tend to narrow beam, wider ones are made – they start with wider rolls of aluminum. Where the 14 footer I have been using is 46 inches wide, there are other 14 footers with 60 and 70 inches of beam. Also, many builders offer similar models in two different metal thicknesses. A firm may offer a lightweight john boat made of ,050” thick sheet and a heavy duty model of similar appearance made of ,064” material. So with this variation in beam and material, you can understand why there is some variation in power recommendation despite an overall similarity in appearance and design.

Similarly, weight varies. A lightweight 14-footer may weigh only 80 to 100 pounds, a medium-weight one around 125 to 150 pounds and a heavyweight one from 175 to 200 pounds. You see, the john boat is now so highly developed that you have to shop around and know something about them before selecting a particular one!

If very low cost and handiness is your need, there are 10 and 12 footers that sell for not too much over $50, with $60 to $70 about average, and weigh a mere 60 to 70 pounds. Thanks to the moderate width, such boats will slide into the open rear end of a station wagon easily, where many prams and dinghies are a few inches too wide to fit. With station wagons as common today as they are, it is getting so that boats that fit into station wagons are giving some very stiff competition to boats meant to be carried on sedan roofs. This figures, for it is much easier to lift any small craft to the level of a station wagon’s tailgate than it is to hoist the same thing overhead. A growing safety problem is small craft sticking out behind station wagons, ready to be shoved into the driver’s seat in a rearend collision. You can even push yourself against your steering wheel by forgetting the projecting boat when backing up and turning around in cramped quarters. A good, sturdy checkrope that will deter the boat from going forward against the seat is a wise thing for those who do any appreciable amount of station wagon boat hauling.

At the other end of the size range, big 18 and 20 foot john boats are becoming popular as work boats for all kinds of jobs. They are used by engineers and surveyors, commercial fishermen, resort owners and so on. A big 20-footer will carry upwards of a ton of freight and might have as much as 50 horsepower. This is quite a bit of transportation capability for a price hovering around the middle hundreds. Some john boat makers are even offering models on which are mounted simple cabins.

While these shelters will never win any prizes for beauty, they are as practical as the shelters people put up for rural children to stand in while waiting for the school bus to come. They keep supplies dry while being ferried to a camp, and they give good protection against rain and wind while out fishing. Definitely not open-water boats, they are nevertheless worth serious thought by coastal dwellers who like to go out on reasonably protected bays and estuaries for certain kinds of fishing during the chillier months. With a canvas curtain closing off the rear and a portable stove going, the cabin becomes a warming hut into which one can duck after half an hour of bottom fishing or casting from the wide, level forward deck or the after cockpit. Plenty of room, too, for four or six fishing pals in an 18-footer.

The typical john boat will pound when going into a chop, but as speed is moderate this is seldom bad enough to cause complaint. Sometimes the flat of the forward end will butt short, steep waves and throw up a sheet of spray. You can see if moving passengers aft helps matters when this happens. Some john boats have a moderate amount of vee put into the upturned bottom toward the bow, which tends to push water aside rather than beat it down. There is more upturn to the bow in some makes than in others, and one maker puts a blunt vee into the usually flat forward transom. When shopping for a john boat keep an eye on this variation in detail.

Again emphasizing that I am not boosting the john boat as a seagoing craft, it can be said that here is a type of boat that more and more salt water sportsmen will be looking at seriously from now on for certain uses. If offers low original cost, can give good performance with moderate power, is light in weight and easy to manage, needs practically no maintenance, shrugs off rot and corrosion, won’t warp or distort when stored outdoors, carries a heavy load, has shallow draft, beaches easily, rows fairly well, is roomy enough to be a happy fishing platform, is easy to transport and tows well behind larger boats. At this winter’s boat shows, give the homely john boats a close look. You may get some happy ideas and end up with a fine utility boat for use on the more protected parts of the ocean.

Practical Tenders

For over 30 years I have been writing articles for boating magazines. As you can readily understand, the question “What shall I write about next?” is constantly on my mind.

Ideas come from all kinds of places. The many readers who have written kind comments about my efforts have helped me keep in touch with what’s on their minds and thereby to think up appropriate subjects. Sometimes a news release from a marine firm, or a few good publicity photos, gives me an inspiration. And, I pick up ideas in the course of my own boating.

Recently I spent a day at the waterfront and found myself watching people come and go from the dock in their yacht tenders. Some were using rickety old prams that appeared ready to fall apart or open a seam at any moment. I watched them ferry overly heavy loads. I saw them using dinghies without the slightest apparent awareness of proper boat balance and oarsmanship. Despite a state law requiring personal flotation gear in each and every boat, I saw tender after tender come and go with no sign of buoyant cushions or life jackets aboard. All this made an impression on me.

That prams, dinghies, punts, john boats, inflatables and similar tiny craft can get into trouble is attested to by what one reads in the newspapers. Each season we see a number of sad stories that tell how lives were lost when such craft foundered while carrying overloads from ship to shore on dark nights, swamped on blustery days, or when a sudden motion caused occupants to fall overboard. In spite of this we never see boating safety authorities do anything aimed specifically and energetically at this obviously serious problem.

Regulations and design standards dealing with flotation provisions and stability, the carrying of life preservers, capacity labels, exhortations to use common sense afloat, and even decals calling attention to marginal transverse stability in boats such as the narrower john boats, are all well and good as far as the overall small-boat scene is concerned. But all of this does seem to strike at the pram and dinghy problem in a rather roundabout way that does not appear to be getting through to people who chance one day to find themselves using a dinghy and quite unaware of its special collection of quirks. Perhaps if I tell you what I know of them, you can make good use of this information for your own safety, and pass it along to others so that much-needed insight on this class of boat will spread as widely as possible.

When we think of tenders, we’re apt to visualize the kind of craft seen behind and aboard larger yachts. What does this have to do with using boats for salt water fishing? Plenty! Yachtsmen are not the only people who use tenders. Plenty of fishing enthusiasts use them too. Often sport fishing boats are kept at moorings well away from yacht basins and marinas, and their owners depend on beached tenders to get to and from them – often encountering rough water due to the exposed locations of many such mooring sites.

Often enough, too, we see tender-type boats being used for actual fishing. Some sportsmen buy them because they can readily and easily be transported in station wagons. Some own them because they can’t afford a larger craft, don’t use one often enough to warrant keeping one, or have no place to keep one. Prams and dinghies have been used for all kinds of unusual purposes, having served their owners as drink cooling tubs at parties, for wash tubs while cruising, for working on larger boats at such tasks as cleaning marine growths from around the waterline, for exploring strange coves before entering with larger craft, for carrying anchors away from grounded boats to pull them free, and you-name-it. There isn’t a fisherman around who at one time or another does not find himself making use of a tender!

To understand boats in this class, it’s useful and interesting to look into the origin and history of common types like the dinghy and pram. The word “dinghy” is derived from the Bengali dingi, which is described as “a kind of East Indian rowing boat, a light rowboat or skiff, often a tender.” In times past a dinghy could be anything up to a rather large rowboat able to hold several persons and used as a sailing vessel’s tender. In modern practice, it usually implies a smallish rowboat, normally only six to eight feet long, and typically of round-bottom and often handsome design.

Our word “pram” has no connection with the British colloquial word “pram” applied to a baby’s perambulator. Rather, it is derived from the old German pram and the Dutch praam, both referring to “a small lightweight nearly flat-bottomed boat with a broad transom and squared-off bow.” In modern American usage it generally means a row-boat of dinghy size, but with hardchine hull and either flat or vee bottom.

Small boats of conventional wood plank construction have to be soaked in the water for a while so their planks will swell and close the seams tightly. But, normal tender service calls for constantly popping a craft into and out of the water. Before World War II most dinghies were either of lapstrake or canvas-covered, canoe-type construction, both methods providing a hull that is watertight at all times and does not need soaking-up.

Because steam-bent ribs are used in these constructions, such boats of necessity were round bottomed. It is natural and quite understandable that round bottomed boats as small as the average dinghy should be unsteady and often quite cranky in the water. Before World War II your average yachtsman was the studious and dedicated sort of soul who worshipped seamanship; he had the knowledge and feel for boats necessary to handle a dinghy capably. But today every Joe Landlubber is apt to take a fancy to a boat he sees on display. He buys it, grabs whatever is in sight that looks as if it’ll serve as a tender, and starts his boating career with about as much insight on the nature of the beast as a New Guinea tribesman has of racing cars.

A more experienced and knowledgeable boatbuilder could point out that any short, wide boat is poorly proportioned for easy rowing and that a nice round bottom can improve matters in this regard. All right, in the hands of a capable oarsman such a boat can be safe! But today imitation and copying are rife in the boatbuilding business and often johnny-come-lately boatbuilders who have no insight on small boat history start making round-bottom dinghies of fiberglass. They don’t know oldtimers were forced to use round bottoms because they built over steam-bent ribs. They think their round-bottomed fiberglass versions look nice, and they do in fact sell well to other newcomers.

But, if you look around you will notice that where round-bottomed fiberglass outboard hulls patterned after older wooden ones were commonplace a score of years ago, nobody today active in the highly competitive, rapidly-changing outboard boat manufacturing field makes round-bottomed fiberglass outboard boats today! Fortunately, the versatility of fiberglass is encouraging dinghy and pram builders to venture into other hull shapes, some of them quite meritorious. Anyone who feels he likes and wants a round-bottomed dinghy is entitled to have one, but it is in the public interest for today’s average pleasure boat enthusiast to be aware of the anachronistic aspects of round-bottom dinghies made of fiberglass.

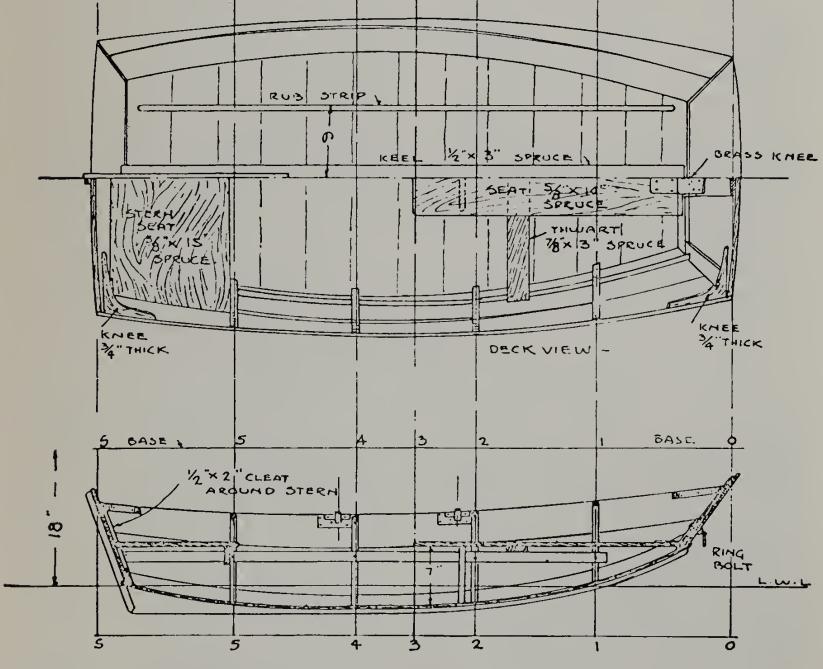

As it originally appeared in this country, the pram was a flat-bottomed boat with cross-planked bottom. American yachtsmen presumably saw native prams in northwestern Europe, liked their merits of low cost and compactness, and brought some home with them. Accompanying this article is a drawing of what could be called an Americanized version of such prams. It was designed in the 1930’s by the late William Atkin, a naval architect of great skill and a profound student of the art of small-boat design. You will be amazed at how much we today can learn from a study of this little pram which Atkin named Rinky Dink!

Waterproof plywood appeared on the scene in the years just before and after World War II. Pram builders eagerly adopted it because it lent itself to a quickly-built, inexpensive, watertight hull. It has always been common to outfit dinghies with simple sailing rigs so the children of cruising families could use them for fun while their parents relaxed aboard yachts. Presumably to make the new plywood prams duplicate as nearly as possible the underwater hull shapes and sailing characteristics of the round-bottom dinghies whose sailing rigs they adopted, prams began to appear that had a substantial amount of vee in their bottoms. Good for sailing, perhaps, but not for stability and steadiness when used as oar-propelled tenders!

Quick and cheap to make, thousands upon thousands of this type were produced by kit-boat manufacturers, small boat yards and mill-work shops – and they’re still about the most common type of tender to be seen on the waterfront.

Sometimes, some vee in the bottom of a tender is desirable to help make it tow better behind a large boat. A truly flat bottom tends to slither along over the water and can get to yawing badly. But even a little vee in a bottom makes it tend more to “plow a groove” in the water and this makes it want to go straighter and steadier. This can be a useful feature on a tender that is going to spend a lot of time at the end of a towline.

However, using vee isn’t the only way of making a tender tow well. Refer to the drawing of Rinky Dink and note the generous skeg and rub strips on her bottom. The former will work to keep her pointing straight when under tow and the latter afford resistance to skidding or slithering about. Note also how low on the bow the ring bolt is. A leading reason why some tenders yaw badly when being towed is because the tow line is attached too high on the bow. It tends to pull the bow down into the water, resistance builds up on the forward part of the hull, overpowers the guiding effect of the skeg, and the tender begins yawing.

As you can see on the Rinky Dink drawing, a towrope angling down from the top of a towing boat’s transom will tend to lift Rinky’s forward parts. The bow can bob and rise over waves in the towboat’s wake and the skeg is kept well down in the water so it can work well.

Riding along in bow-up, stern-down attitude, Rinky’s “center of lateral area” is well aft of amidships and the skeg has a strong effect in keeping her pointed straight. More often than not, a tender that tows poorly can be made to behave by this simple trick of attaching the towline lower on the bow.

A towed tender can become a nuisance or even a menace when the sea is rough. Eventually enough water can splash into one to weigh it down considerably. The water will slosh to one side, put the gunwale down, and sea water will spill aboard. Then the tender will corkscrew and dive deep. The tow line may part, or it may rip the bow out of the tender. Or if things hold fast, the submerged tender’s drag can decelerate the tow boat appreciably. If it happens to be a sailboat running fast with the wind, a mast backstay could snap or the sail blow out. If it’s a powerboat negotiating rough seas, pooping or broaching could result.

So sometimes it is necessary to take the tender aboard and lash it down where it can do no mischief. To facilitate this, they are sometimes made as small as ingenuity can manage so that they can be stowed in any available space. The man who needs a tender to row out to a moored boat does not need one of these abnormally small tenders.

Both when making one of these dwarf tenders and when making one of more generous size to carry a load out to a moored boat, a designer will strive to get as many cubic feet of hull volume as he can into the smallest possible overall dimensions. Suppose we wish to make a tender eight feet long, four feet in beam and eighteen inches deep. Within these limits, one shaped like a box will have the greatest possible volume and will carry the heaviest possible load – but it’ll row and handle abominably.

We therefore rework the box to give it a pointed bow. That makes it row better – but some volume has been taken away and it will not have as much buoyancy. Trying to make it sail better to please the kids, we rework it more to give it a vee bottom. That takes away more hull volume. Now look at the top view of Rinky Dink. That wide, blunt bow is a workable way to retain as much volume as possible within given length and breadth limits. It also gives more room inside, compared to a pointed bow, to carry people or duffel bags. Yet William Atkin’s keen eye for shape has produced a craft that coaxes our eyes into believing that Rinky Dink is not as boxy-looking a boat at all! He did it by incorporating a lively, jaunty sheer line.

Notice that the bottom is dead flat in the transverse sense. This retains as many precious cubic inches of hull volume as possible, for good buoyancy. As a bonus, the flat bottom gives a craft that, considering its smallness, is reasonably steady underfoot when one is clambering in or out of it.

Round-and-vee-bottom tenders are wide enough so they’re not too apt to dump you by rolling completely over; but their apparent wideness is a subtle trap for the unwary. Often overlooked is the fact that such bottoms will let a tender roll quickly through the first several degrees of heel. Eventually they “stiffen up” when the low side goes deep enough in the water, which is why they are not likely to actually capsize. But, it’s that first short, quick roll that does the dirty work. It catches people by surprise, makes them lose their balance and fall overboard. Then the boat pops itself upright and drifts quickly away from them – carrying the life preservers with it!

Another advantage of having pronounced “rocker” in the bottom of a tender as seen from the side, is that it makes the boat very easy to pivot quickly with the oars when maneuvering to come alongside a motorboat or dock, or dodging mooring lines. But, boat design is basically a matter of making compromises. We cannot have everything in a boat. Although the rocker in Rinky Dink’s bottom contributes to easy rowing and good maneuverability, it contains a booby trap. If someone should step quickly or even jump into either the bow or stern end of this or any other tender like it, that end will promptly go down. In so doing it will force water out from underneath. The opposite reaction to thus accelerating several gallons of water in one direction is that the tender will be pushed in the other direction!

So, much to the lubber’s surprise, the tender will shoot forward or backward under his feet, they’ll go out from under him, and he will join the statistics with a loud kersplash! In general, you get into any tender with as much caution as you use when lowering yourself onto a bronco at the rodeo.

Once aboard, the matter of rowing comes up. If you’re alone, you naturally sit on the amidships thwart. If you’ve got two companions, and provided the tender is buoyant enough and the water acceptably calm, you can have them lower themselves into the bow and stern seats. Either way, you have a well-balanced boat that floats level and handles as nature intended.

But if you have just one companion – a common situation – you’ve got a problem. Put him or her in the stern seat and that section of the tender goes down until there are two, maybe three, inches of freeboard. Shift him forward and you get the same awkward situation at the other end. Look now at the drawing of Rinky Dink. Notice how the oarsman sits on a seat that runs fore and aft in the boat instead of athwartships. That’s the difference between a copycat boat and a boat thought out and designed by a man who knows his onions!

Atkin’s “ironing board” seat solves that problem beautifully. Plenty of room to either side of it for you to position your legs comfortably and with knees low to clear the oars, regardless of how long your pins might be. With one passenger aboard, you slide yourself forward a short distance, keep your legs in the same low, comfortable position, shift the oarlocks to the forward set of sockets, and go happily rowing off with your tender well balanced and riding level.

All this is not to say that Rinky Dink is the best tender in the world; I have just used it as a good example with which to illustrate the features that make for a good one. The insight on tender quirks you have learned from studying Rinky Dink, you can apply to any other tender you contemplate buying or are forced to use.

It’d be nice if some company would mass-produce and widely distribute a really outstanding tender. Trouble is, no one boat will serve all the various purposes under the “tender” classification. The man who uses one to row from he beach to a moored boat doesn’t need an abbreviated one; he’s better off with an able craft of ten or twelve feet. It’s one thing to tow a tender behind a sailing yacht that cruises at five or six knots, but modern powerboats with planing hulls cruise at twenty or thirty knots and a towed tender would get such a banging around that in such cases the prudent skipper ends up carrying his tender aboard the big boat. He, of course, shops around to find one that will fit any available space. Sometimes he can find no space where a rigid dinghy will fit, so ends up settling for an inflatable rubber boat that can be rolled up and put in any available space. So the market for tenders remains very fragmented and it’s hard for any manufacturer to sell enough of one particular type in enough volume to justify creating a really outstanding design.

“John boat” types made of aluminum are now being sold by discount houses at prices comfortably under $100. As these are cheap and durable, many people are adapting them to use as tenders. Sometimes they work out well, sometimes not. Note again the rocker in Rinky Dink’s bottom. When she is propelled by a small outboard, water pushes up on the forward part of her bottom and, above rowing speed, sucks down on the after part. This will make her “squat,” or plow along bow-up and stern down. The deat flat bottom characteristic of the john boat resists squatting and helps carry outboard power.

On the other hand, john boats’ flat, rockerless bottoms make them hard to pivot under oars and so they can be awkward to maneuver. And, they are not rough-water boats. Visualize one on choppy water, when it is in the trough between two waves, the amidships section isn’t deeply immersed, but the bow and stern ends are well down in the water of the waves ahead and behind. A hull with lots of rocker like Rinky Dink keeps her ends high and dry when the boat is in the trough between two waves, so foundering is less likely. You really have to shop around and do some thinking to choose a tender that will serve your particular needs to best advantage.

Many craft offered the tender buyer today are built to a price. By the time a man has bought his boat and major accessories, he’s apt to feel like economizing. You find cheap fiberglass dinghies with oarlocks held on with a couple of pop rivets or small machine screws that soon pull loose under the pressure of oars. You find vacuum-molded polyethylene craft with no gunwale padding at all and they can be hard to repair. All I can do is drag out two timeworn cliches:

“One man’s meat is another’s poison” and “You pays your money and takes your choice.”

A vital point to bear in mind is, when you have three men in an eight-foot pram, you have a very heavy load in a very small boat and the plain truth is that in such a situation, good seamanship and a feel for boats is as vital – if not even more so – as it is when you’re skippering a forty-footer. The tragedy of it all is, it’s often the people who are abysmally ignorant of boats and seamanship that are often found in prams and dinghies.

Never buy a tender without actually trying it out on the water. When sides are low, such as on john boats, oarlocks also sit low and oars can be hard to manipulate without fouling your knees. Or with three aboard some prams, you can’t work the oars without banging the knees of the person just aft of the oarsman’s position. Insist on a water trial so you will be sure the craft you get is really rowable and manageable.