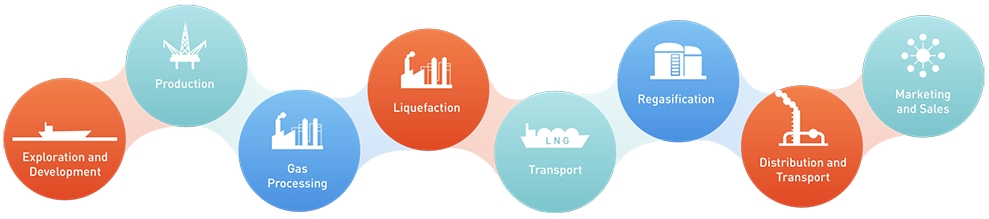

The LNG value chains starts upstream with exploration and production operations. It then proceeds through the midstream stage of processing and transportation, and then the downstream phases of liquefaction to shipping and distribution to the consumer.

Government and private sector partners need to develop trust and firm long-term commitments that enable relationships in each part of the chain to endure. In order to build this trust, compromise, and a cooperative, rather than adversarial, approach to negotiations is important.

The LNG value chain is only as strong as its weakest link. The development of all portions of the chain must be carefully coordinated to avoid project failures that can result from missed connections. Accommodating both LNG exports and local supply (domestic gas) within the available natural gas resource base will be important to maintaining host country support for the production, processing, and export portions of the project. If the gas and LNG value chain does not result in the development of domestic supply infrastructure, it will be difficult to sustain the rest of the value chain, ensure that all parties profit, and promote long-term harmony between the producers (international oil companies or IOCs), exporters or importers (to include both commodities and technology), infrastructure developers, customers and the host country.

LNG Value Chain

Ensuring that LNG projects create value for all participants requires that each link in the chain fully performs its contractual obligations within a framework of trust and commitment. Failure of one link adversely affects other key links. Contracts must set forth integrated rights and responsibilities and must set up the long-term relationships, which require joint planning, coordination, and flexibility. Successful value chain management should help ensure completion within budget, timeliness of start-up, safe and reliable operations within and across links, and the ability to overcome changes in the market and operating conditions.

LNG is not currently a commodity business and continues to be dominated by long-term contracts. A spot market and shorter-term contracts are emerging due to commercial and geopolitical factors. “Base load” sales of LNG are long term, typically 20-25 years with take-or-pay provisions to limit risk. LNG projects are capital intensive and it is currently harder to make the whole value chain appear profitable in the face of lower prices and projected market over-supply. Fully dedicated shipping is often required. Dedicated shipping is capital intensive and project financing depends on creditworthy partners, firm agreements and a reliable LNG value chain.

Market uncertainty caused by increasing supply competition, limited demand growth, and competition from pipeline supplies, are driving shippers and suppliers to attempt to sell cargos allocated to term contracts, or new cargos, on spot markets to cover the capital costs of LNG ships and infrastructure.

Pipelines have point-to-point rigidity and geographic inflexibility making it difficult to supply islands or mountainous countries or regions fragmented by geopolitical issues, trade barriers, or security conflicts. LNG may provide a competitive supply option if pipeline supply cannot profitably surmount long distances and challenging routes. LNG might also be considered if the buyer has security-of-supply concerns, insecure borders, or deep oceans to be crossed.

The above graphic provides a depiction of the LNG value chain.

Exploration Development and Production

The LNG value chain begins with the drilling and production of natural gas from subsurface gas reservoirs. This exploration and production (E&P) and development activity has historically been dominated by national oil company (NOC) partnerships with international oil companies (IOCs). This is particularly the case in less developed countries with stranded reserves far from major markets – due to large capital requirements and the need for experienced operators. Smaller international companies and national oil companies are increasingly involved in exploration and production activities but may lack experience in working with the full value chain.

US markets have introduced new upstream dynamics. Large gas reserves were developed by a variety of suppliers that are able to connect to and ship gas through existing infrastructure to large markets. This has somewhat mitigated the high capital costs and risks and helped to ensure a high return on investment, though it would be difficult to replicate this in other countries.

Production optimization methodologies can help to manage costs and help to understand the key value drivers and risks across upstream production processes. Thorough and detailed strategic planning is key to success at this stage. Asset plans and strategies identify the long-term requirements for physical assets and match production levels at all phases of the project with planned supply to local and export markets.

These stages provide direction and guidance to enable the creation of investment and maintenance plans – essential to putting in place the resources (including finance) to manage the assets consistent with achieving desired outcomes. Agreements must be in place so that the other links are proceeding apace to accept the gas and begin supplying consumers.

Natural Gas Conversion

| To Convert | ||||||

| billion cubic metrs NG | billion cubic feet NG | million tonnes oil equivalent | million tonnes LNG | trillion British thermal units | million barrels oil equivalent | |

| From | Multiply by | |||||

| 1 billion cubic metrs NG | 1 | 35,3 | 0,90 | 0,74 | 35,7 | 6,60 |

| 1 billion cubic feet NG | 0,028 | 1 | 0,025 | 0,021 | 1,01 | 0,19 |

| 1 million tonnes oil equivalent | 1,11 | 39,2 | 1 | 0,82 | 39,7 | 7,33 |

| 1 million tonnes LNG | 1,36 | 48,0 | 1,22 | 1 | 48,6 | 8,97 |

| 1 trillion British thermal units | 0,028 | 0,99 | 0,025 | 0,021 | 1 | 0,18 |

| 1 million barrels oil equivalent | 0,15 | 5,35 | 0,14 | 0,11 | 5,41 | 1 |

Processing and Liquefaction

The gas supply that comes from the production field is called “feed” gas and this feed gas must be sent to a processing facility for treatment prior to liquefaction. While natural gas used by consumers is almost entirely methane, natural gas is associated with a variety of other compounds and gases such as ethane, propane, butane, carbon dioxide, sulfur, mercury, water, and other substances. Sometimes gas is also produced in association with oil and sometimes liquids are produced in association with gas. Most of these compounds must be removed prior to the liquefaction process.

Once the impurities and liquids are removed, the natural gas is ready to be liquefied. At the liquefaction plant, the natural gas is chilled into a liquid at atmospheric pressure by cooling it to -162 °C (-260 °F). In its liquefied form, LNG takes up about 1/600th of the space of the gaseous form, which makes it more efficient to transport.

Liquefaction plants are typically set up as a number of parallel processing units, called trains. Each train is a complete stand-alone processing unit but typically there are multiple trains built side by side. Liquefaction is the most expensive part of the value chain.

Read also: Manual for Engineers to Calculate Amount of Gas in Reservoirs

Some countries are considering floating liquefaction solutions due to environmental issues and the remote location of resources offshore. In floating liquefaction, all processes occur on the vessel at sea. The same liquefaction principles apply but the marine environment and limited space for equipment on the vessel require slightly different technology solutions.

Source: Freeimages.com

From a commercial standpoint, liquefaction is historically dominated by NOC/IOC partnerships and specialized contractors are required for the construction of liquefaction facilities. High capital costs are typically financed across a long development cycle of several decades. The LNG development project team must finalize bankable commercial structures for LNG projects, possibly including both onshore and floating solutions.

Careful project management and assurances that the local authorities are supportive of the project are required to bring in the costly design and execution service companies. It is critical that agreements are in place to allow for shipments to credit worthy offtakers (customers) so that the government and companies can begin to recover costs and generate revenues.

Planned supplies to the domestic market also need to be productively allocated and relevant processing and transportation need to be in place so that the local authorities and citizens will see more direct benefit from the project.

Shipping

Once the natural gas is liquefied, it is ready to be transported via specialized LNG ships/carriers to the regasification facility. LNG carriers are double-hulled ships specially designed to contain the LNG cargo at or near -162 °C.

Asian shipyards dominate the market for LNG ship building since this part of the industry also requires specialized expertise and Asian shipyards have the most experience. Ships are often owned by a shipping company and chartered to seller or buyer. In some fully integrated projects, the ships are built and owned by the project consortium. The Qatar projects are a prime example of this. High capital costs and highly leveraged financing often bring low risk to the ship-owner but also sometimes generate a low return on investment. If the ships are not owned by the project consortium, agreements need to be in place to assure that ships arrive when the terminal begins operations. If local supplies are planned, it is also critical that infrastructure to support pipeline deliveries, trucking and/or smaller local maritime shipping is also planned and in place. Local consumers must also be prepared to accept shipments or provisions must be made for allocated gas to be redirected until consumers are prepared to use the gas.

Regasification and Storage

At the regasification stage, LNG is returned to its original gaseous form by increasing its temperature. Regasification usually occurs at an onshore import terminal that includes docking facilities for the LNG carrier, one or more cryogenic storage tanks to hold the LNG until regasification capacity is available, and a regasification plant. The LNG development project team must finalize bankable commercial structures for LNG import projects possibly including both on-shore and floating solutions. Specialized cryogenic expertise is required for import facilities, but the capital costs are much lower relative to upstream and liquefaction. Siting and permitting terminals can be very challenging and will require agreements with local stakeholders.

Agreements must be in place early in the development process to ensure that the regasification capacity is available to accept the LNG when the liquefaction project is completed.

LNG Units Conversion

| Units | |||

| 1 metric tonne | = 2204,62 lb. | = 1,1023 short tons | |

| 1 kiloliter | = 6,2898 barrels | ||

| 1 kiloliter | = 1 cubic meter | ||

| 1 kilocalorie (kcal) | = 4,187 kJ | = 3,968 Btu | |

| 1 kilojoule (kJ) | = 0,239 kcal | = 0,948 Btu | |

| 1 British thermal unit (Btu) | = 0,252 kcal | = 1,055 kJ | |

| 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) | = 860 kcal | = 3 600 kJ | = 3 412 |

Distribution and Transport to Final Market/Sales

Key aspects of these stages include the ability to factor in volume, price, and supply/demand to best position parties to negotiate and satisfy agreements for transportation, distribution, and sales. Buyers and sellers must account for changing (and potential for change in) local and international market conditions. LNG marketing and trading require careful design so that revenues are generated to satisfy all stakeholders and allow for expansion if that is part of the project plan. Countries will need to assure the implementation of infrastructure required to derive maximum domestic benefit from the LNG value chain, including the construction of power and gas infrastructure required for delivery to consumers.

Domestic Gas Value Chain

The domestic gas value chain begins with production, and proceeds to processing and treatment. Processing and treatment remove impurities and petroleum liquids that can be sold separately where available in commercial quantities (for petrochemicals, cooking gas, and so on). The gas can then be compressed into a pipeline for transmission, distribution, and sale to consumers. In many countries, the gas aggregator, which is in many cases the national gas company, markets the gas to customers and operates the infrastructure.

Source: Pixabay.com

Many national governments mandate the allocation of gas to the domestic market as this allows the development of local industries, including use as a feedstock and as fuel for power generation. Small markets will take time to develop and for the initial years of market development the most likely customers for domestic gas are power plants and existing and planned large industries.

Although supplying gas to the domestic market is an aspiration of the government, developing a commercially viable and financeable project plan based on domestic markets requires careful planning and structuring. A thorough economic analysis is required to ensure that the industry consumers are viable and the entire value chain is financially sustainable.

Hand in hand with the development of gas-fired generation, appropriate wholesale and retail market rules and institutions are a critical feature assisting in the formation of a viable domestic gas monetization plan.

Unlike an LNG take-or-pay contract with one or several large customers, the integrity of the systems to collect bill payments from potentially thousands or millions of end-users in the domestic market can be a key challenge for credit risk management.