Explore a comprehensive collection of common sailboat rigs, their types and designs. Learn about cats, cat ketches, sloops, cutters, yawls, ketches, schooners, and motor sailers to enhance your understanding of sailboat rigging.

The rig, or sail plan, is a critical factor in any boat’s performance. The most important considerations in selecting the rig are the type of sailing you intend to do and the ease of handling and performance you expect. Following is a brief review of each type of rig, together with the primary factors that should be considered as you approach a decision.

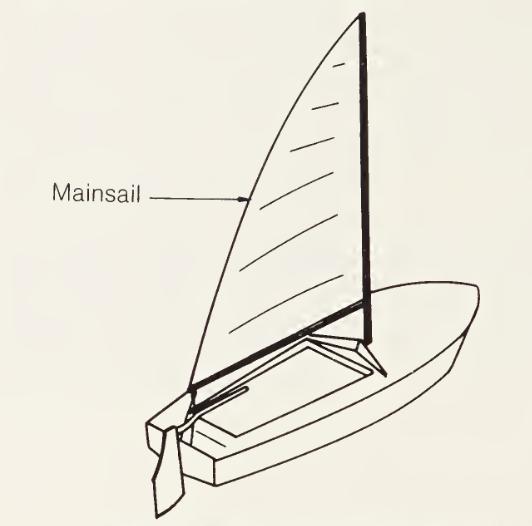

Cats

The cat rig has a single mast stepped quite far forward in the boat, often almost at the bow. A single large sail (main) is carried behind the mast. This sail is usually attached to a long boom that extends almost back to the transom. The main may be gaff or Marconi rigged, although the more efficient Marconi sail now predominates.

The cat sail plan is theoretically the most efficient of all rigs because the sail sets in “clean” air with no turbulence from foresails and also because setting it near the boat’s centerline permits a close tacking angle to the true wind. In light wind conditions, however, the cat has no upwind sails beyond the main, in contrast to boats rigged with foresails, which can set deck-sweeping genoas.

As the cat gets larger, this lack of versatility becomes more of a disadvantage. To support the same sail area as a boat with two or more sails, the aspect ratio (the ratio between a sail’s height and width) of the cat’s main must be higher (in other words, the sail must be narrow and tall).

This results in a more powerful sail with a longer luff, but the stability of the boat also begins to be affected as the mast gets overly high. The main also gets too big for the crew to handle, thus putting a practical limit on the size of a single masted cat-rigged boat (about mid-thirties in feet).

New Design Cats, Cat Ketches, and Cat Schooners

These are popularized developments based on the traditional cat rig, utilizing one or more masts. Foresails are not typically rigged. The working sail area is limited to one or two very large high-aspect ratio sails rigged behind the masts. For running and reaching, spinnakers and staysails can be set. These rigs are currently being combined with a variety of innovative developments. Some builders use a standard boom or no boom (which requires a loose-footed main).

Others have resorted to a wishbone boom, which acts as a permanent vang and, with lazy jacks, self-stows the sail. Unstayed masts are typically used, and some builders are experimenting with rotating wing masts. Sails run the gamut from battenless with roller furling to full battens and even fixed wing sails. The biggest advantage of these new cats is the ease of handling that results from the elimination of foresail changes. The one disadvantage, other than their experimental character, is a lack of good upwind performance in light conditions because of their inability to set genoas in addition to their “working” mains and mizzens.

Sloops

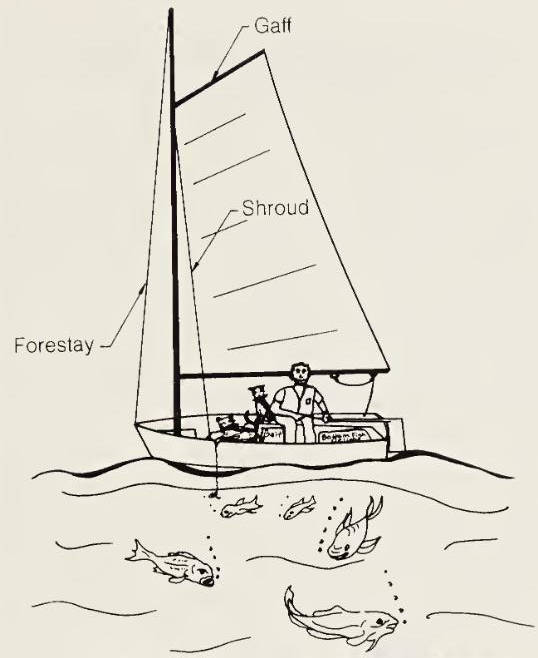

The sloop has a single mast, carried farther aft than on the cat. Most modern sloops have the mast stayed close to the fore-and-aft centerline, permitting larger headsails to be used. The sloop normally sets two sails, a main of small to moderate size behind the mast (usually on a boom) and a jib or genoa in front of the mast from a jibstay (usually also the forestay of the boat). Although the sloop is theoretically less efficient, it is extremely versatile.

It can set a wide variety of foresails, from storm jibs for survival conditions to decksweeping genoas for light air. It also permits splitting the sail plan to balance the boat properly and to reduce the sail area of each single sail to more manageable proportions. Because of these attributes, the modern Marconi-rigged sloop with a large foretriangle is the most popular sail plan on cruising and racing sailboats.

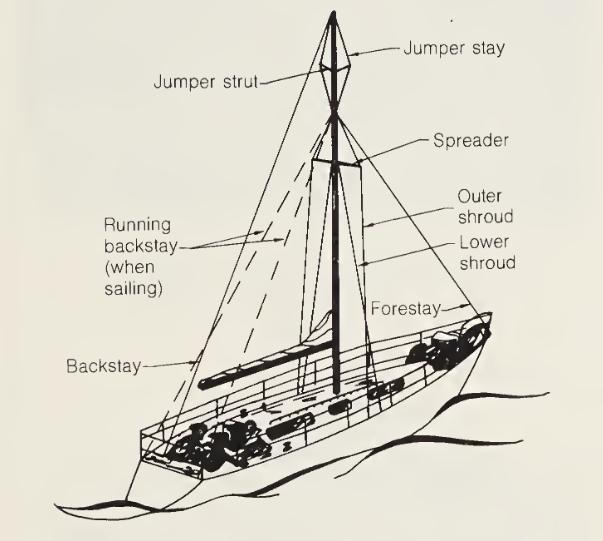

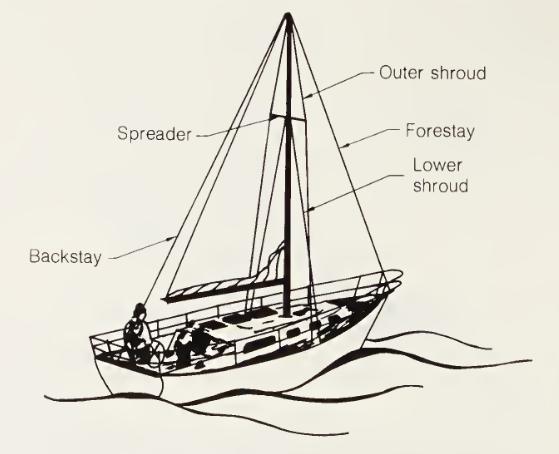

There are two basic types of sloops, fractional and masthead. On a fractional sloop, the forestay is attached to the mast at some point below the masthead. A fraction is used to describe how high off the deck the forestay is attached, with the normal range running from 3/4 to 15/16.

Read also: Characteristics of Different Types of Construction Materials

As a result of the fractional attachment, jibs and genoas are smaller and the main a proportionally larger part of the drive of the boat. Rig tuning is more versatile, with extensive fore-and-aft bending of the mast possible. Tuning is also more complicated, however, and the rig often requires running backstays to support the mast where the forestay attaches.

On a masthead sloop, the forestay attaches to the top of the mast. This rig supports larger jibs and genoas. Carried to an extreme, the main is little more than a stabilizing or balancing sail. Since this sail plan will support much larger genoas, the total potential sail area is greater than with the fractional sloop, an advantage in light wind conditions. Mast tuning is also easier with this rig.

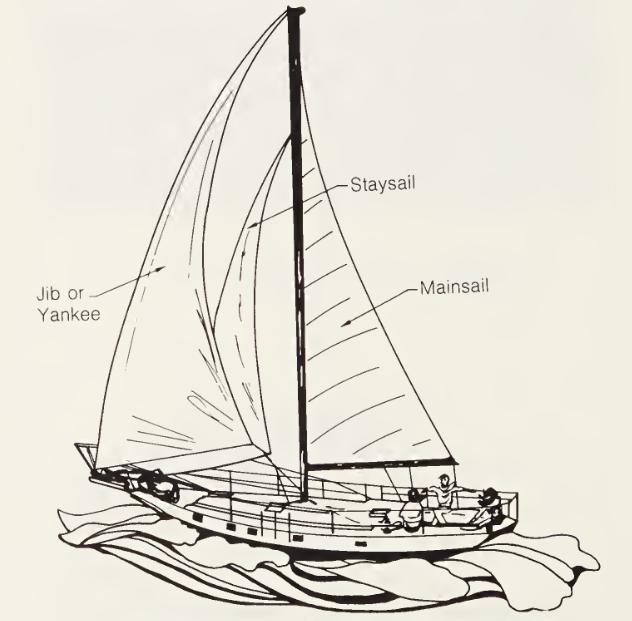

Cutters

The cutter also has a single mast and a main, but it has two foresails – a staysail on an inner stay and a jib or yankee on the forestay. Many cutters can be sailed as sloops by detaching the inner stay and replacing the jib with a large genoa. Conversely, staysail sloops can set up an inner stay and carry a staysail. This rig won’t point as high into the wind as the sloop or cat, but it offers another level of versatility since the sails are broken down into smaller increments (as a rule of thumb, the average sailor can handle a single sail in the range of three hundred to six hundred square feet).

This eases sail handling and permits a wider variety of sail combinations as wind and weather conditions change. The cutter rig usually starts getting serious consideration as a boat approaches forty feet LOA or if the crew is shorthanded.

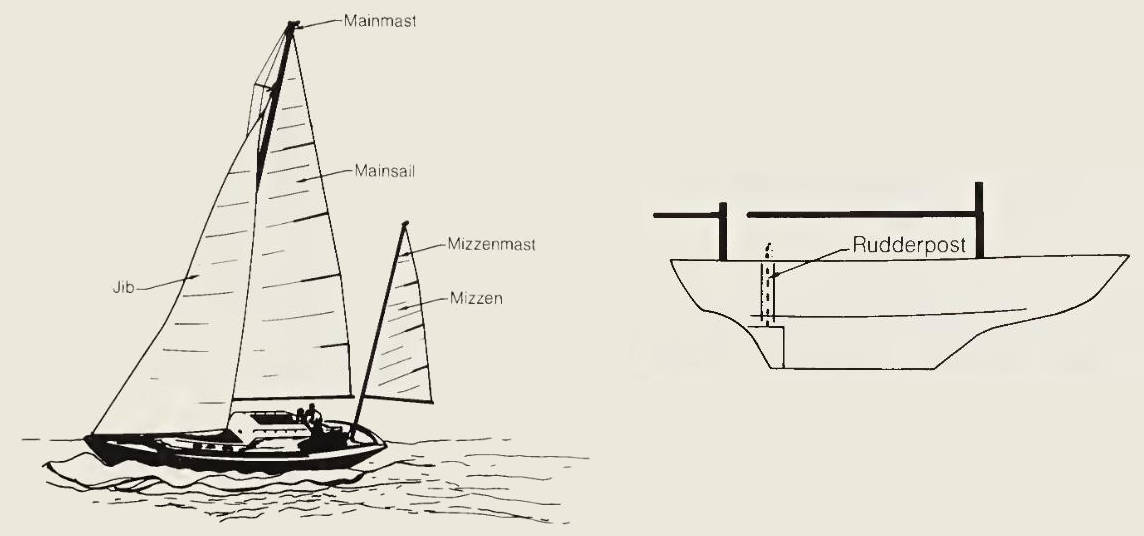

Yawls

The yawl has two masts, with the mizzen or stern mast being much smaller than the main mast and located aft of the rudder post. The yawl will not point as high as the cutter if it is rigged and sailed double-headed (as a cutter with staysail and jib).

The mizzen is often backwinded when beating and when running, the mizzen can blanket either the main or one of the foresails. Because of these characteristics, knowledgeable owners of yawls often beat and run with the mizzen furled.

Designers only credit mizzen sails at 50 percent of their area when doing performance calculations. The mizzen performs best when the boat is on a reach, particularly if a mizzen staysail or spinnaker is set.

It also makes a great anchor sail by keeping the boat weather-vaned into the wind and chop. The two masts and sets of rigging make a yawl a more costly and complex alternative compared with another boat of equal sail area with a single mast.

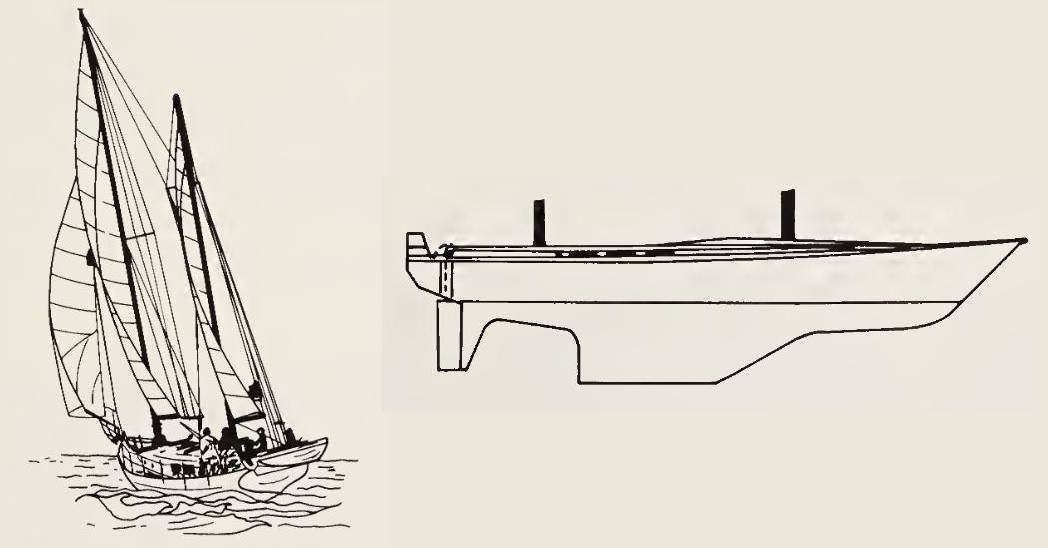

Ketches

The ketch also has two masts, but the mizzen is much larger than on a yawl – from 60 to 80 percent of the height of the main and located forward of the rudder post. Almost everything said about yawls applies to ketches, except that the mizzen is a much larger portion of the ketch’s drive. The foresails are often rigged like a cutter, with a jib and staysail. The biggest advantage of the ketch is that it further divides the sail plan, making sail handling easier and requiring fewer sail changes.

A disadvantage not generally shared with the yawl is that the position of the mizzenmast often confuses the cockpit layout. The shorthanded crew usually begins to get seriously interested in the ketch as a boat approaches fifty feet LOA, though some energetic cruisers and single-handers have sailed cutters and even sloops up to sixty feet and longer.

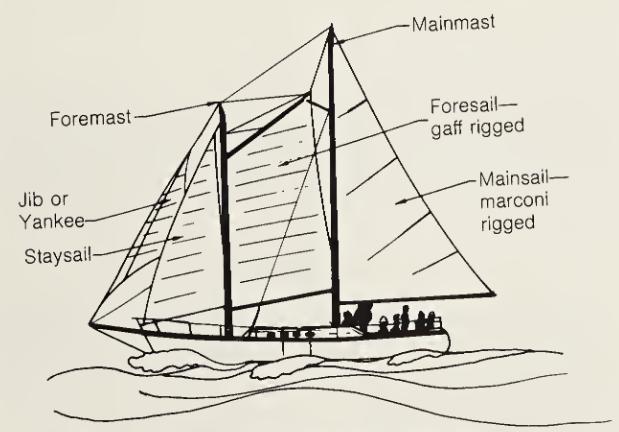

Schooners

The schooner has two or more masts, with the main mast the same height or higher than any of the foremasts. Again, the advantages and disadvantages are similar to those of the ketch and yawl. The schooner goes to windward more poorly than any of the rigs discussed, and the blanketing effect of the main when running is even more pronounced.

The schooner can also be nasty to steer downwind, unless the main is reefed down early to balance the boat and prevent a broach. The schooner is probably the most versatile of the rigs because of the variety of sails that can be set. If only working sails are compared, it is usually superior to the other sail plans on a reach.

Motor Sailers

Motor sailers can have any of the various rig configurations already discussed, but cutter and ketch rigs seem to predominate. The single most important distinction of a motor sailer is the size of its engine and the shape of the hull. Motor sailers are designed to motor more than a sailboat with an auxiliary engine.

Consequently, engine size, fuel tanks, propellers, and hull shape favor motoring. Since less sailing is intended, the sail plan is usually smaller. This, of course, reduces performance under sail and provides a further incentive to motor, a potentially vicious cycle.

Motor sailers can be classified according to their engine power versus their sail power. In one system of classification the spectrum may run from the 20/80 motor sailer (with 20 percent of the characteristics of a motorboat and 80 percent of the characteristics of a sailboat) to the 80/20 motor sailer. A 20/80 motor sailer might have a sailboat hull, a moderate size sail plan, and a large engine. The 80/20 motor sailer might have a motorboat displacement hull with a very large engine (capable of speeds in excess of displacement speed) and a minimal sail plan used only for balancing the boat and helping out downwind. In addition to having less sail area, motor sailers are generally heavier than other sailboats. Their design also usually includes high freeboard, inside steering stations, and pilothouses.

In addition to performing better under power (many sailors actually power more than they sail), the motor sailer usually offers more room and comfort than a true high-performance sailboat. They often make good live-aboard boats for the boater who can’t completely give up sails, and in northern climates offer superior protection from the elements.