Discover the fascinating story of the Titanic building, from its innovative concept and detailed section drawings to the monumental task of building one of the world’s largest ships. Uncover the charm and inner workings of this iconic liner in a comprehensive exploration of her creation and legacy.

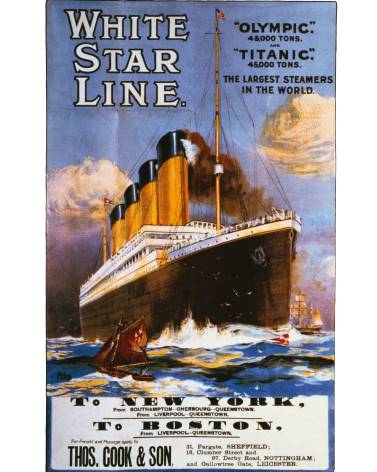

The Royal Mail Ship Titanic was an Olympic-class passenger liner. It was originally conceived as the largest, fastest and safest ship in the world.

The era of Titanic marked the apogee of transatlantic luxury cruising. In a time before air travel, the grand ocean liner was the most impressive and luxurious form of transportation in the world, the embodiment of both opulence and man’s continuing achievement. But the ships that plied the oceans were also the result of competition founded on the burning desire for financial profits.

In 1839, Samuel Cunard won a contract with the British government to provide a fortnightly mail service from Liverpool to Halifax and Boston. Within a year, the Cunard Line had produced Britannia, the first purpose-built ocean liner. Soon afterwards, other new Cunard ships – Acadia, Caledonia and Columbia – joined Britannia in the first regularly scheduled steamship service to North America, taking approximately 14 days for the passage. For the next three decades, the Cunard Line remained virtually unchallenged.

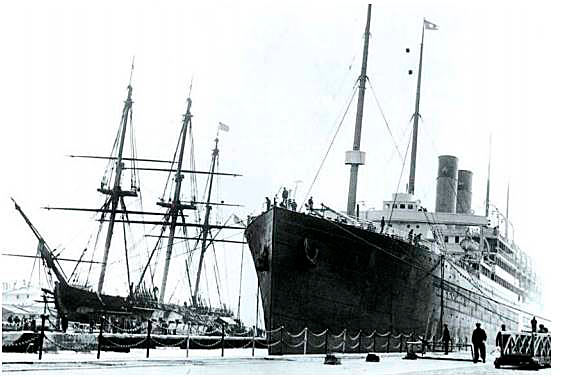

Meanwhile, the White Star Line, which was founded in the 1840s, developed a strong business taking immigrants to Australia. Within a couple of decades, however, White Star had fallen on hard times, and in 1867 it was taken over by Thomas Henry Ismay. It was not long before Ismay and several colleagues had transformed the company, replacing the old wooden clippers with new iron steamers and entering the Atlantic market. They soon formed a business partnership with renowned Belfast shipbuilder Harland & Wolff, which agreed to construct all of White Star’s ships.

The first product of the new alliance, Oceanic, appeared in 1871, complete with numerous design improvements. Within a few years, White Star’s Adriatic, Baltic and Germanic had successively won the Blue Riband, the prize awarded to the ship making the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic, and the journey time had dropped to less than seven and a half days.

For the next 20 years, Cunard and White Star battled for supremacy, each successively making faster and more advanced ships to accommodate the increasing number of passengers crossing the Atlantic. White Star’s challenge to Cunard did not go unnoticed. In 1888, the Inman and International Line launched City of New York and City of Paris. These were not only extremely elegant, but their twin screws eliminated the need for sails while allowing them to be the first ships to cross the Atlantic eastbound at an average of more than 20 knots.

Cunard and White Star quickly responded. White Star emphasized passenger comfort, with Harland & Wolff’s chief designer Alexander Carlisle producing Teutonic and Majestic, the first modern liners. These were ships without sails, with a much greater deck space; accommodation was situated at midships rather than at the stern. Meanwhile, Cunard’s focus was primarily on speed. In 1893, the company introduced two new ships, Campania and Lucania, which promptly won back the Blue Riband.

Largest and Fastest City of New York and City of Paris were stunning achievements because they were the first liners weighing more than 9 072 tonnes (10 000 tons), while also having the speed to gain the Blue Riband. The following ships are those that held the distinction of being the world’s largest liner at the same time as holding the speed record for crossing the Atlantic. NDL = Norddeutscher Lloyd CGT = Compagnie Générale Transatlantique; WB = westbound; EB = eastbound

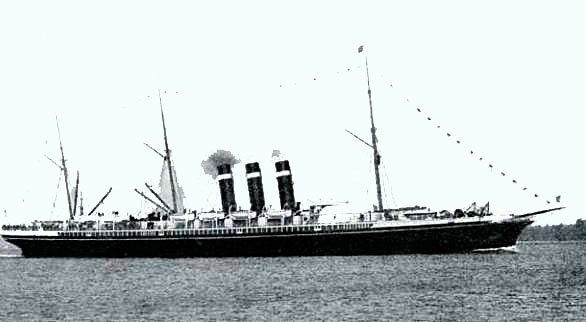

New competition soon appeared from the Germans, highlighted in 1897 when Norddeutscher Lloyd produced Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She was the largest, longest and fastest ship afloat, and one that sported four funnels: a new look that would dominate the years to come.

Not everyone was enamoured of such rivalry, however, as fierce competition did not lead to the greatest revenue. One man determined to put profit first was American financier John Pierpont Morgan. Morgan’s goal was to set up an alliance of shipping companies under one banner, allowing them to set rates and eliminate expensive advertising and other competitive costs, thus increasing profits. Between 1900 and 1902, Morgan’s investment house and several of his business associates orchestrated a series of mergers and share sales that allowed what became the International Mercantile Marine Company (IMMC) to take control of a number of American and British shipping lines.

The jewel in Morgan’s new shipping crown was the White Star Line. Shortly thereafter, a cooperative pact was established with the main German shipping lines. The only major player that now stood in the way of the IMMC having complete domination of the Atlantic passenger trade was Cunard.

The Concept

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Cunard, the last major transatlantic shipping line with strictly British ownership, was under threat of takeover by J P Morgan’s IMMC, which had already acquired the Dominion Line, Red Star Line, Holland-Amerika Line and, in 1902, the White Star Line. In addition, Cunard ships were being outperformed by Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and a new, even faster ship: Deutschland of the Hamburg-Amerika Line.

It was clear that Cunard needed faster, more lavish ships to compete with the Germans and the IMMC, but the company did not have the funding, so Lord Inverclyde, Cunard’s chairman, turned to the British government for help. Set against a backdrop of British unease with growing German power, he negotiated a multimillion-pound loan and an annual subsidy. In return, Inverclyde guaranteed that he would keep Cunard under British control, that the two new ships Cunard built would bring back the Blue Riband and that they would be able to be turned into armed cruisers in case of war.

In mid-1907, the first of these two new liners, Lusitania, came into service and, although at 28 622 tonnes (31 550 tons) she was the largest ship in the world, her power was so enormous that she quickly regained the Blue Riband in both directions. Before the end of the year, however, her sister, Mauretania, replaced her as largest at 28 974 tonnes (31 938 tons), and also earned the Blue Riband for eastbound travel, proving so fast that she held on to the title for the next 22 years.

The IMMC responded to Cunard’s challenge that very year. On the death of his father in 1899, J Bruce Ismay had become chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. He had kept his position when the company had been taken over, then in 1904 had become president of the IMMC, although J P Morgan maintained the ultimate power.

In 1907 Ismay and Lord Pirrie, chairman of Belfast shipbuilder Harland & Wolff, decided on a revolutionary course of action that they hoped would regain the initiative from Cunard. Their grand concept was to build two huge liners, with a third to follow later.

The Competition In order that Cunard could put both new ships into service as quickly as possible, Lusitania and Mauretania were built at separate shipyards. This resulted in a competitive spirit that saw the shipbuilders incorporate every innovation they thought might make their respective ship the best. Although they appeared similar on the outside, the interiors contrasted starkly with one another: Lusitania’s gold leaf on plaster gave it an open, airy feeling, while the oak, mahogany and other dark wood of Mauretania produced a more sober, subdued atmosphere. Although Mauretania was faster, Lusitania ultimately proved more popular with passengers.

These would dwarf the Cunard ships, being about 30 metres (100 feet) longer and, at 41 730 tonnes (46 000 tons), half as large again. Rather than attempting to equal the speed of Mauretania, the new ships would concentrate on elegance, luxury, comfort and safety, while also still being able to complete the Atlantic passage within a week. Even the lower speed would be beneficial, as it would reduce the engine noise and vibration that plagued Lusitania and Mauretania. Moreover, the new ships would be so large that they would benefit from economy of scale, their unrivalled lavishness appealing to large numbers of first-class passengers, and second- and third-class passengers also finding larger and better facilities than on any other ship.

«…We are in a state of war in the Mediterranean trade, in the Atlantic trade both passengers and freight (the Provision rate being 3/- per ton), and much fear from my latest advices that we are in for a serious upheaval in Australia and New Zealand, but shall do everything possible to avert the latter… Well, I have undertaken a big job, and look to you to help me all you can, and feel sure I can rely on your loyal and hearty help and support. Again thanking you for your kind cable, and trusting Mrs. Pirrie and you are well, and with my kindest remembrances to both…» – J Bruce Ismay

The only weakness in the plan seemed to be that there was no shipyard in the world with the facilities to produce such mammoths. That did not stop Pirrie, who simply converted three of Harland & Wolff’s largest berths into two specially strengthened and lengthened slipways. Over them, William Arrol and Company, builder of the famous Forth Rail Bridge, constructed a gantry that rose 69,5 metres (228 feet) to the upper crane. Measuring 256 by 82,3 metres (840 by 270 feet) and weighing more than 5 443 tonnes (6 000 tons), the gantry was the largest such structure in the world. At the same time, Ismay began discussions with the New York Harbor Board about lengthening the White Star piers. He was initially refused, but when J P Morgan began pulling strings, the desired permissions eventually came through.

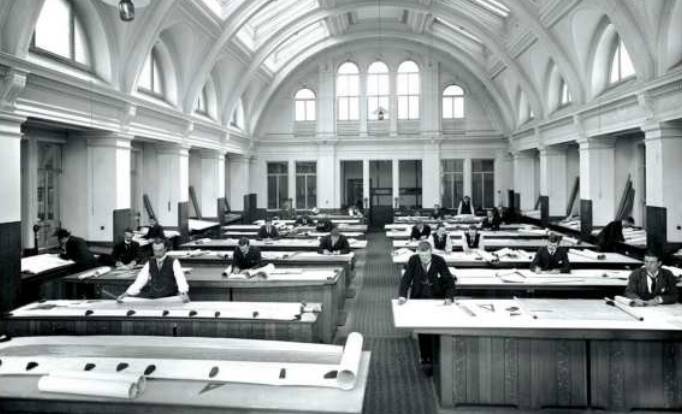

Meanwhile, plans for the first two ships were drawn up by a team at Harland & Wolff, under the guidance of the general manager for design, Alexander Carlisle, Pirrie’s brother-in-law. In July 1908, Ismay travelled to Belfast, where he approved the design plans. The building of the largest ships in the world could now commence.

What Kind of Engine? One of the key questions for shipbuilders at the start of the twentieth century was whether to power ships with traditional, piston-based reciprocating engines or with the more recent steam turbine. Cunard tested this in sister ships brought into service in 1905. Carmania’s steam turbine proved faster and more economical than Caronia’s reciprocating engine, leading Cunard to put turbines in both Lusitania and Mauretania. Similarly, White Star’s Megantic used reciprocating engines and her sister Laurentic a combination of the two engines. Based on Laurentic’s success, combination engines were designed for Olympic and Titanic.

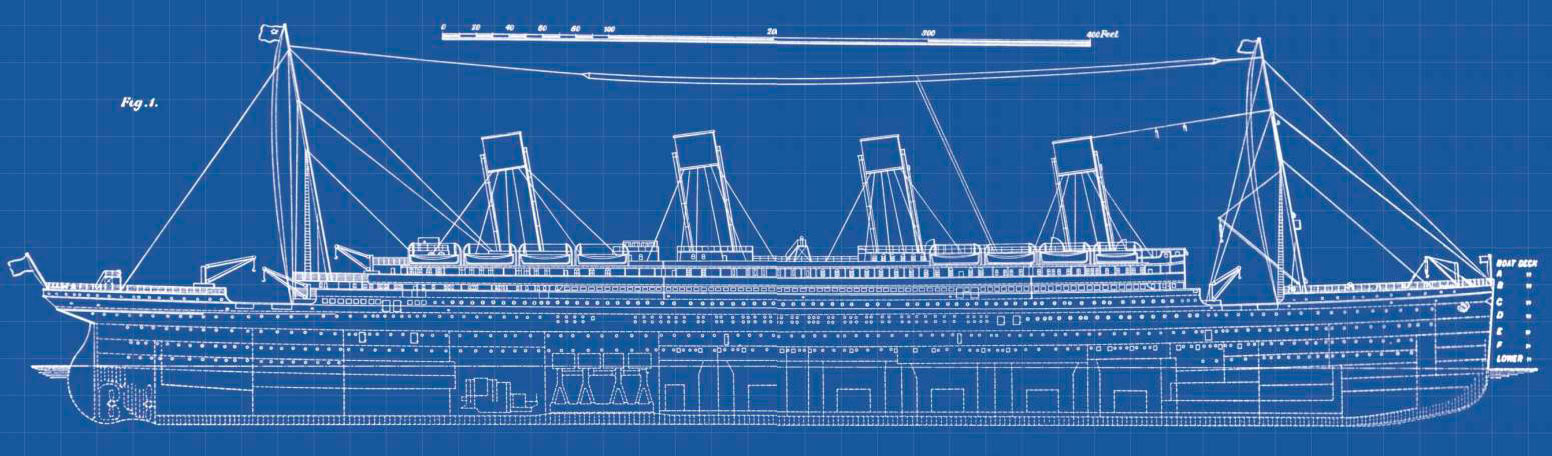

A Section Drawing of The Giant Liner Titanic

Previous Great Shipping Disasters. Following are some of the principal disasters at sea that have occurred in recent years:

| Lives Lost | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | September 20: Olympic (captain Smith in command) in collision with H. M. S. Cruiser Hawke in Cowes Road | – |

| 1910 | February 9: french steamer General Chanzy wrecked off Minorca | 200 |

| 1909 | January 23: Italian steamer Florida in collision with the White Star liner Republic, about 170 miles east of New York, during fog. Large numbers of lives saved by the arrival of the Baltic, which received a distress signal sent up by wireless from the Republic. The Republic sank while being towed. | – |

| 1908 | March 23: Japanese steamer Mutsu Maru sank in collision near Hakodate | 300 |

| 1907 | February 2: G. E. R. steamer Berlin wrecked off Hook of Holland during gale | 141 |

| 1906 | August 4: Italian emigrant ship Sirio, bound for South America, struck a rock off Cape Palos | 350 |

| 1905 | November 19: L. S. W. R. steamer Hilda struck on a rock near S. Malo and became a total loss | 130 |

| 1904 | June 15: General Slocum, American excursion steamer, caught fire at Long Island Sound | 1 000 |

| 1902 | May 6: Govermorta lost in cyclone, Bay of Benga | 739 |

| 1991 | April 1: Aslan, Turkish Transport, wrecked in the Red Sea | 180 |

| 1899 | March 30: Stella, wrecked off Casquets | 105 |

| 1898 | October 14: Mohegan, Atlantic Transport Co. steamer, wrecked on the Manacles | 107 |

| 1896 | December 7: Salier, North German Lloyd steamer, wrecked off Cape Corrubebo, N. Spain June 16: Drummond Castle, wrecked off Ushant | 281 247 |

| 1895 | January 30: Elbe, North German Lloyd steamer, from Bremen to New York, sunk in collision with the Crathie, of Aberdeen, off Lowestoft | 334 |

| 1893 | June 22: H. M. S. Victoria, sunk after collision with H. M. S. Camperdown | 359 |

| 1878 | March 24: H. M. S. Eurydice, wrecked off Dunnose Headland, Isle of Wight | 300 |

| 1852 | February 26: Troopship Birkenhead struck upon a rock off Simon’s Bay, South Africa. The heroism displayed by the men on board has earned them undying renoun | 454 |

| The Titanic’s Larder The Titanic took on board at Southampton just before she sailed: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Meat (lbs) | 75 000 | Potatoes (tons) | 40 |

| Poultry (lbs) | 25 000 | Ale and Stout (bottles) | 15 000 |

| Fresh Eggs | 35 000 | Minerals (bottles) | 12 000 |

| Cereals (lbs) | 10 000 | Wines (bottles) | 1 000 |

| Flour (barrels) | 250 | Electroplate (pieces) | 26 000 |

| Tea (lbs) | 1 000 | Chinaware (pieces) | 25 000 |

| Fresh Milk (gals.) | 1 500 | Plates and Dishes (pieces.) | 21 000 |

| Fresh Cream (qts) | 1 200 | Glass (pieces) | 7 000 |

| Sugar (tons) | 5 | Cutlery (pieces) | 5 000 |

| The World’s Largest Ships The Titanic took on board at Southampton just before she sailed: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Tonnage | Length, feet | Breadth, feet | Speed, knots | |

| *GIGANTIC | 50 000 | 1 000 | 110 | – |

| *AQUITANIA | 50 000 | 910 | 95 | 23 |

| *IMPERATOR | 50 000 | 910 | 95 1/2 | 22 |

| TITANIC | 46 328 | 883 | 92,6 | 22 1/2 |

| OLYMPIC | 45 324 | 883 | 92,6 | 22 1/2 |

| MAUETANIA | 31 938 | 762 | 88 | 25 |

| LUSITANIA | 31 550 | 762 | 87 | 25 |

| * Building or projected | ||||

Building the Biggest Ships in the World

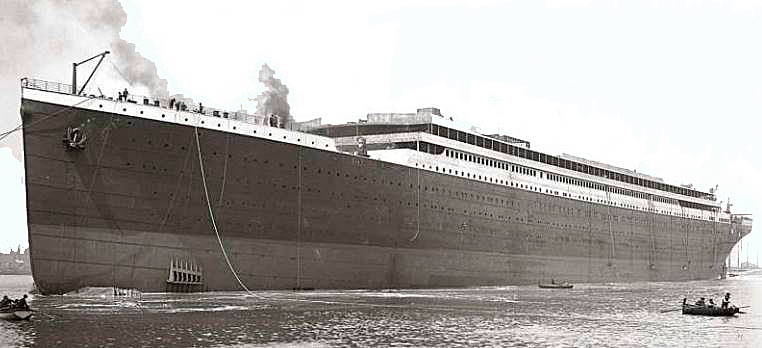

The first task that now faced Harland & Wolff was to develop the infrastructure that would allow the monster ships to be built. Throughout the latter half of 1908, the two new giant slipways were prepared and the gantry constructed high above them. Finally, on 16 December 1908 at Slip Two, the first keel plate was laid for what would become Olympic. Then, on 31 March 1909, next door at Slip Three, a similar keel began to be laid. It was Harland & Wolff’s keel number 401, and the ship that would rise from it would become known as Titanic.

The two ships were virtually identical in their initial construction. Up from the keel rose powerful frames that were set from 0,6-1 metre (2-3 feet) apart and were held in place by a series of steel beams and girders. Steel plates up to 11 metres (36 feet) long were riveted on the outside of the frames. Each ship had a double bottom, comprising an outer skin of 2,5-centimetres – (1-inch-) thick steel plates and a slightly less heavy inner skin. This was a safety measure designed to keep the ship afloat if the outer skin was punctured. So massive was the double bottom that a man could walk upright in the area between the skins. To hold all this together, more than half a million iron rivets were used on these lower reaches of Titanic, some areas even being quadruple-riveted. By time the ship was complete, more than three million rivets had been used.

The original plans produced by the design group under Alexander Carlisle reflected the latest thinking in marine architecture. The hull, for example, was divided into 16 compartments formed by 15 watertight transverse bulkheads. It was believed these made the ships essentially unsinkable, as it was claimed they could float with any two of these compartments flooded. However, the bulkheads were built as a protection against the kind of accident that had occurred in 1879, when the Guion Line’s Arizona had rammed an iceberg in the fog. Although the bow of Arizona was virtually destroyed, the collision bulkheads had prevented her from sinking and she had been able to steam back to St John’s, Newfoundland, stern-first. Thus, to many, Titanic seemed invincible because her extensive bulkhead system protected her from similar damage; unfortunately, however, it did little to protect the enormously long sides that proved to be the ship’s most vulnerable region.

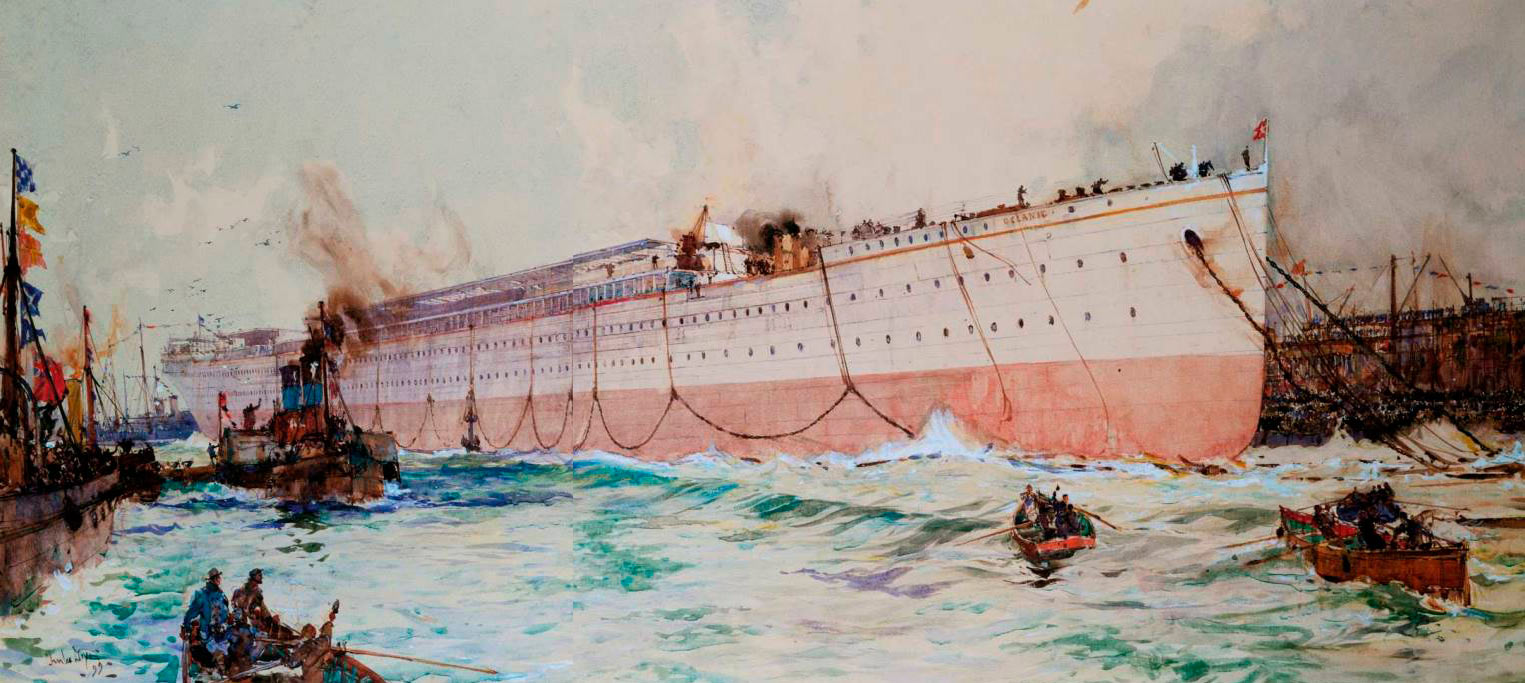

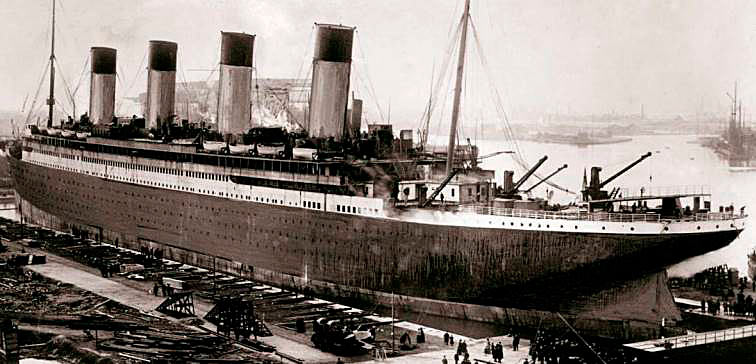

Throughout 1909 and into 1910, more than 4 000 employees of Harland & Wolff worked on Olympic and Titanic . When Carlisle retired in 1910, he was succeeded by Pirrie’s nephew, Thomas Andrews. Finally, in October 1910, Olympic was launched and towed to her fitting our basin to be completed. Work also continued on Titanic, and on 31 May 1911, the same day Olympic was handed over to the White Star Line, the hull of Titanic was launched. Her dimensions were staggering. If placed on end, she would have been taller than any building in the world at the time: 269,1 metres (882 feet) – about four New York City blocks. Even sitting upright she would be as high as an 11-storey building.

The launching of Titanic was a momentous occasion, with an estimated 100 000 people – one-third of Belfast – turning out to watch. J P Morgan, who had come from New York for the occasion, arrived on the chartered steamer Duke of Argyll, along with more than 100 reporters from England. Shortly before 12:15 pm, Lord Pirrie ordered the last timber supports to be knocked away. Moving under her own weight, in 62 seconds the 21 772-tonne (24 000-ton) hull slid down a slipway greased with 20 tonnes (22 tons) of tallow, soap and train oil. As thousands cheered, the hull slipped into the water until being halted by special anchors.

After the launch, the hull of Titanic was towed to a deep-water wharf, where, during the following months, a giant floating crane was used to load:

- engines;

- boilers;

- electrical generators;

- refrigeration equipment and all of the other heavy machinery needed to run what would effectively become a small town.

She received three anchors totalling 28 tonnes (31 tons), eight electric cargo cranes and, far above, four funnels – the three front ones were connected to the boiler rooms, with a dummy aft funnel positioned over the turbine room, to which it supplied ventilation. Carlisle’s original plans included only three funnels, but the fourth had been added to enhance the lines of the ship. Each was so vast that a train could be driven through it. With the basic equipment in place, many more months were spent outfitting and detailing, producing what was widely considered the most impressive ship in the world.

| Titanic’s Specifications | |

|---|---|

| LENGTH: | 269,06 metres (882 feet, 9 inches) |

| BEAM: | 28,19 metres (92 feet, 6 inches) |

| MOULDED: | 18,13 metres |

| DEPTH: | (59 feet, 6 inches) |

| TONNAGE: | 46 329 gross; 21 831 net |

| PASSENGER DECKS: | 7 |

| BOILERS: | 29 |

| FURNACES: | 162 |

| ENGINES: | Two four-cylinder, triple expansion reciprocating of 15 000 hp apiece, one low-pressure steam turbine of 16 000 hp |

| SPEED: | Service, 21 knots; max, approximately 23-24 knots |

| MAX PASSENGERS AND CREW: | 2 603 passengers, 944 crew |

| LIFEBOATS: | 16 + 4 collapsible (1 178 capacity) |

«For months and months, in that monstrous iron enclosure there was nothing that had the faintest likeness to a ship, only something that might have been the iron scaffolding for the naves of half a dozen cathedrals laid end to end. At last a skeleton within the scaffolding began to take shape, at the sight of which men held their breaths. It was the shape of a ship, a ship so monstrous and unthinkable that it towered over the buildings and dwarfed the very mountains by the water.» – A Belfast observer

Building the Biggest Ships in the World

«I was on the Titanic from [when] they laid the keel ‘til she left Belfast… Well, I loved it, I loved it, and I loved my work and I loved the men, and I got on well with them all… If you had seen or known the extra work that went into that ship, you’d say it was impossible to sink her.» – Jim Thompson, a Harland & Wolff caulker

The Glamour of Titanic

By the end of her outfitting, Titanic had become the most luxurious and elegant ship in the world, and one that could not fail to impress. The designers had even learned from the early voyages of Olympic, following which Titanic received several alterations before going into service. The major change to the exterior was the addition of a glass canopy with sliding windows along the first-class promenade on A deck, so that the passengers would be protected from bad weather and sea spray.

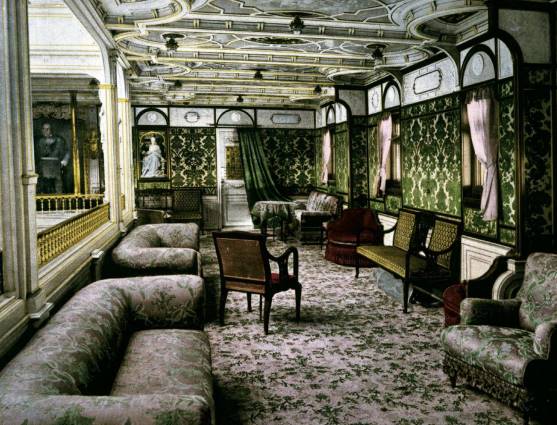

The interior was extravagantly grand, and first-class passengers were treated to staterooms, public rooms, fittings and furnishings, and food that could be expected from the finest hotels and restaurants in the world. Yet although the ship was strictly segregated by class, it was as impressive for those in second- and third-class as for the wealthier passengers. In fact, second-class bettered that of first-class on most other liners, while third-class surpassed the accommodation and amenities of second-class on other ships.

Each class had its own dining saloons, smoking rooms, lounges or libraries, stairways and promenades. In addition to three first-class elevators, there was one for second-class: a first on any ship. Nothing was more spectacular than the forward grand staircase (there was also a similar one aft), which was covered by a massive glass dome and extended downwards for five levels, from the first-class entrance on the boat deck to E deck, the lowest level on which there were first-class cabins. Accommodation on A, B and C decks was reserved for first-class passengers, who were also able to enjoy:

- luxurious reading rooms;

- a palm court;

- gymnasium;

- swimming pool;

- squash court;

- Turkish baths;

- their own barber shop and even ivy growing on trellised walls.

The first-class staterooms were decorated in the style of different design periods, including:

- Italian Renaissance;

- Louis XIV;

- Georgian;

- Queen Anne and current Empire.

They varied from one to three berths, and some incorporated an adjoining or nearby cabin for a personal servant.

Many of the first-class staterooms were en suite, but some of the less expensive ones (they varied between £ 263 and £ 25 11s 9d) shared a washroom. The 207 second-class cabins, located on decks D, E, F and G, were serviced by their own splendid staircase, and consisted of mahogany furniture in two-, three- or four-berth cabins set off oak-panelled corridors that were carpeted in red or green. Many ships housed third-class immigrants in open berths in large, dormitory-style rooms; although Titanic did have some of these (the least expensive fare was less than £ 7), there were also 222 third-class cabins with pine panelling and attractive floor coverings. For those who were housed in the dormitories, single men and women were kept well separated – men in the bow and women in the stern.

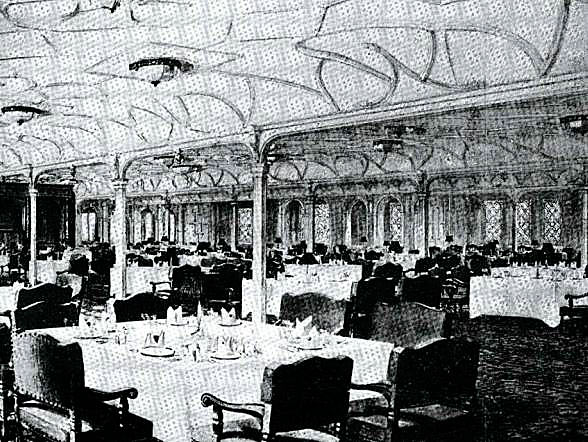

The first-class dining saloon was the largest room on Titanic, extending 34,7 metres (114 feet) for the entire width of the ship, and catering for 550 people at a time. First-class passengers could also enjoy an à la carte restaurant, the Verandah Café at the palm court or the Café Parisien, which quickly became a favourite with the younger set.

First-Class-Suites There were numerous first-class suites on Titanic, but the most expensive were the four parlour suites on decks B and C. Each of these had a sitting room, two bedrooms, two wardrobe rooms and a private bath and lavatory. Thomas Drake Cardeza and his mother Charlotte occupied the suite on the starboard side of B deck, paying £ 512 6s 7d, the most for any passengers aboard; this price also included cabins for their two servants. On the port side, opposite the Cardezas, J Bruce Ismay’s suite included its own private 15,2-metre (50-foot) promenade.

On D deck, the second-class dining saloon, which could seat 394 people, was panelled in oak, like the second-class smoking room, whereas the large second-class lounge featured sycamore panelling and upholstered mahogany chairs.

For third-class dining, there was a 30,5-metre – (100-feet-) long saloon on F deck. Seating 473 passengers, it was relatively basic, and was divided in two by a watertight bulkhead. However, compared with the dining arrangements on other ships, where long, bolted-down benches and crowded quarters were the order of the day, it was vastly superior, featuring smaller tables as well as the luxury of separate chairs.

This remarkable venue could seat 550 people and included Jacobean-style alcoves along the sides

«We can’t describe the table it’s like a floating town. I can tell you we do swank we shall miss it on the trains as we go third on them. You would not imagine you were on a ship. There is hardly any motion she is so large we have not felt sick yet we expect to get to Queenstown today so thought I would drop this with the mails. We had a fine send off from Southampton and Mrs S and the boys with others saw us off. We will post again at New York then when we get to Payette.» – Harvey Collyer

| Food Loaded Aboard Titanic The food loaded aboard Titanic in Southampton prior to departure for the week-long trip included: | |

|---|---|

| Food | Weight |

| Fresh meat | 34 000 kg (75 000 lb) |

| Poultry & game | 11 350 kg (25 000 lb) |

| Fresh fish | 5 000 kg (11 000 lb) |

| Bacon & ham | 3 400 kg (7 500 lb) |

| Salt & dried fish | 1 815 kg (4 000 lb) |

| Sausages | 1 135 kg (2 500 lb) |

| Eggs | 40 000 |

| Potatoes | 35,7 tonnes (40 tons) |

| Rice & dried beans | 4 540 kg (10 000 lb) |

| Cereals | 4 540 kg (10 000 lb) |

| Sugar | 4 540 kg (10 000 lb) |

| Flour | 200 barrels |

| Fresh butter | 2 725 kg (6 000 lb) |

| Fresh milk | 5 678 litres (1 500 gallons) |

| Condensed milk | 2 271 litres (600 gallons) |

| Onions | 1 600 kg (3 500 lb) |

| Oranges | 36 000 |

| Lemons | 16 000 |

| Lettuce | 7 000 heads |

| Tomatoes | 2,4 tonnes (2,75 tons) |

| Green peas | 1 020 kg (2 250 lb) |

| Asparagus | 800 bundles |

| Coffee | 1 000 kg (2 200 lb) |

| Tea | 360 kg (800 lb) |

| Beer | 20 000 bottles |

| Wine | 1 500 bottles |

«But what a ship! So huge and magnificently appointed. Our rooms are furnished in the best of taste and most luxuriously and they are really rooms not cabins. But size seems to bring its troubles – Mr. Straus, who was on deck when the start was made, said that at one time it stroked painfully near to the repetition of the Olympic’s experience on her first trip out of the harbor, but the danger was soon averted and we are now well on to our course across the channel to Cherbourg.» – Mrs Ida Straus

The Workings of Titanic

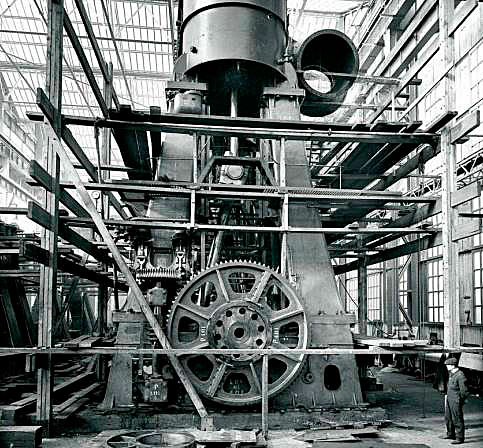

«As magnificent as Titanic was in terms of cabins and public rooms, she was perhaps even more remarkable in areas passengers never saw. Her propulsion came mainly from two four-cylinder, triple-expansion reciprocating engines sending 15 000 horsepower apiece to the massive 34-tonne (38-ton), three-bladed wing propellers. In addition, a 381-tonne (420-ton), low-pressure turbine recycled steam from the other engines, providing 16 000 horsepower to drive the 20 tonne (22-ton), four-bladed, manganese-bronze centre propeller, which had been cast in one piece. This allowed her a projected top speed of approximately 24 knots.»

There were 29 gigantic boilers, most measuring 6,1 metres long by 4,8 metres in diameter (20 feet by 15 feet 9 inches), providing the steam for these engines, at a pressure of 15 kilograms per square centimetre (215 pounds per square inch). The boilers were driven by 162 coal furnaces that were stoked continually by a team of firemen, or stokers, numbering approximately 175.

An average of approximately 544 tonnes (600 tons) of coal was consumed daily from bunkers holding more than 7 257 tonnes (8 000 tons), and an additional 70 «trimmers» were employed to bring it from the bunkers to the firemen at the furnaces.

The figures were just as amazing for the many other technical features housed throughout the colossal ship. The cast-steel rudder was constructed in six pieces, which together measured 24 metres long by 4,6 metres wide (78 feet 8 inches by 15 feet 3 inches), and weighed more than 91 tonnes (100 tons).

Titanic also benefited from electrical power to an extent that was highly unusual at the time. The main generating plant consisted of four 400-kilowatt, steam-powered generators, which produced 16 000 amps at 100 volts: a total that matched many stations in British cities. But such power was absolutely required because there were no fewer than 150 electric motors, complete with hundreds of miles of wire and cable. These serviced:

- 10 000 incandescent lamps;

- 1 500 bells used to call stewards;

- 520 electric heaters;

- a telephone exchange of 50 lines and uncountable passenger signs;

- lifts;

- cranes;

- winches;

- fans;

- workshop tools;

- kitchen and pantry appliances and navigational aids.

The main plant was also the primary power source for the Marconi wireless telegraphy station. With two dedicated operators, the wireless station was located on the boat deck, where it was linked to a double aerial that ran between the two masts more than 61 metres (200 feet) above the water surface. Considered a key safety feature, it had alternative sources of power should the main electricity go down, including storage batteries directly in the operating room.

It was subsequently dismantled and then reassembled aboard Titanic

The generating plant also powered two refrigeration engines, which in turn drove a host of cold rooms. Separate accommodation was provided for different kinds of:

- meat;

- fish;

- vegetables;

- fruit;

- milk and butter;

- beer;

- champagne;

- flowers;

- chocolate and eggs.

Perishable cargo was also housed in cool areas near the main provision stores, and cold pantries and larders, ice-makers and water coolers were placed around the ship, where stewards could meet passengers’ needs easily.

Even the three-part bronze whistles aboard Titanic were something special. Weighing about 340 kilograms (750 pounds) each and standing more than 1,2 metres (4 feet) high, they were the largest whistles ever aboard a ship. They were powered by steam via an automated whistleblowing system that used three chambers with diameters of 38,1, 30,5 and 22,9 centimetres, (15, 12 and 9 inches) for a variation of sound that combined into one sustained blast.

Another design feature that led to Titanic being considered unsinkable was the set of massive watertight doors linking the 15 supposedly watertight compartments. These doors, extending through each bulkhead, were normally held open by a friction clutch. In an emergency, the clutch could, in theory, be released by the captain using a control panel on the bridge. Each door could also be closed individually at its location. Finally, each door was equipped with a float mechanism that would automatically lift and trip a switch to close the door if water entered that compartment.

Because of the size and complexity of the ship, communication throughout it had been carefully considered. The boiler rooms, for example, were linked to the starting platform by a series of illuminated telegraphs, allowing the engineer to communicate with them swiftly and efficiently. Overall, the technological achievements of Titanic were so imposing that, as completion approached, the trade journal The Shipbuilder was able to state she was «practically unsinkable».