Explore the impact of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and their potential dangers to marine merchant vessels. Learn about the risks posed by drones, including security threats, navigation interference, and privacy concerns.

- The Threat

- The Iranian UAV Threat

- Target Selection

- Attack Methodology

- The Houthi UAV Threat

- Drone Insight

- Incident

- Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

- Single Rotor

- Multi Rotor

- Fixed Wing

- Delta Wing

- Drone Catalogue

- Mitigation

- Immediate Actions

- Safe Muster Point

- Mitigation

- Actions on

- Bridge Manning

- Hardening

- Mitigation

- Routing

- Compliance

- Reporting

Perfect for maritime professionals and enthusiasts interested in the intersection of drone technology and marine safety.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly used in conflict areas as a relatively effective and inexpensive means of attacking a target with precision. In the past year, at least four merchant vessels have been struck by UAVs in the Arabian Sea.

Different types of UAVs exist and loitering munitions and commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) are being increasingly utilised in conflict. UAVs can be:

- fixed-wing;

- delta-wing;

- or rotary-wing.

They are designed as surveillance and/or combat UAVs which can be armed with grenades, aircraft ordnance, or constructed to detonate upon impact.

UAVs have recently been used by state actors and non-state actors alike. In recent months Russia, Ukraine, and Iran have made use of these kinds of UAVs.

Iran has developed a range of domestically produced UAVs ranging from small loitering munitions to larger, more durable UAVs carrying aircraft ordnance. The Iranian-produced UAVs are being exported to various actors, most prominently the Houthis and Russia (Geran-2). Iran additionally supplies a range of its UAVs to non-state actors such as:

- Hezbollah;

- Hamas;

- Iraqi/Syrian Islamist militants (such as Kata’ib Hezbollah);

- and the Houthis.

Whilst the Russia-Ukraine war has seen the use of UAVs on the battlefield and less in the Black Sea maritime domain, with the primary target being port infrastructure, Iran and the Houthis have used them to disrupt merchant shipping in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea.

The Threat

War risk is the principal threat to shipping. The threat currently stems from conflict between Russia-Ukraine and Israel/US-Iran, and the countries’ respective regional proxy and allied forces.

Whilst the Russia-Ukraine war has seen the use of UAVs on the battlefield and less in the Black Sea maritime domain, with the primary target being port infrastructure, Iran and the Houthis have used them to disrupt merchant shipping in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. The war between Russia and Ukraine has not yet led to the targeting of merchant vessels with. However, they are being widely used on the battlefield with Russia importing the Iranian-made delta-wing loitering munition, Shahed-136, known as the Geran-2. The Geran-2 will be able to cause similar damage as the Shahed-136 prominently used in Iranian assaults on merchant shipping in the Arabian Sea. The Shahed-136 and others are known as «loitering munitions», which bridge the gap between missiles and non-lethal UAVs, able to be GPS-programmed and then guided toward a specific target. They carry explosive payloads in the nose, designed to explode upon impact. Alternatively, they can be detonated above the target, with a fragmentation charge disseminating shrapnel. This has been observed in footage of a drone attack on a military parade at Al Anad military base in Yemen in 2019.

Although enmity between Iran and various Gulf states has been apparent for decades, the Iran crisis flared in mid-2019 following the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the US ending of third-party sanctions waivers, and reimposition of bilateral sanctions. The State of Israel targeted several Iranian tankers in the Red Sea and East Mediterranean. War risk escalated through 2019, with limpet mine attacks on tankers in the Gulf of Oman, targeted seizures, and missile strikes on key Saudi infrastructure, all of which fell short of the threshold for war. Since, further vessels have been seized and, in a new form of interference, Iran has utilised UAVs to damage Israel-affiliated merchant shipping in the Arabian Sea. The Houthis for their part have used UAVs to disrupt the export of oil and gas products via Yemen Government-controlled ports in southern Yemen by targeting port infrastructure. Tankers have been present during those incidents and sustained minor collateral damage. It should also be recognised that while the Houthis share interests with Iran, they have independent interests.

The UAVs have been known to detonate and cause damage to superstructure or inside a vessel. Hull breaches have so far been above the waterline and small in diameter, reducing the risk of sinking. If the UAV hits the bridge area, it can destroy navigational equipment. In the worst incident to date, two men lost their lives.

The Iranian UAV Threat

It is assessed that, as long as the US continues to impose sanctions and Israel continues to frustrate its regional ambitions, Tehran will continue to exploit the maritime domain for diplomatic messaging and power projection, taking full advantage of its 2 815 km coastline flanking the:

- Gulf of Oman;

- Strait of Hormuz;

- and Persian/Arabian Gulf.

Iran continues to pursue a series of deniable attacks, in an asymmetric manner that makes use of both aerial and waterborne drone systems. The Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) maintains a sizeable and sophisticated UAVs fleet, both independently developed, and reverse-engineered.

Commercial shipping has increasingly become a victim of harassment, seizures, and covert attacks as a result of diplomatic tensions between Tehran and its adversaries. However, the UAVs threat overwhelmingly extends to Israel-affiliated shipping. Said affiliation is ascertained through flag, ownership, or management. Iran has mistakenly targeted vessels in the past, striking vessels that had previously been Israel-linked but not anymore at the time of the assault.

Target Selection

A commercial vessel’s exposure is primarily driven by its:

- state affiliations through the flag;

- ownership domicile;

- management;

- and, to a lesser extent cargo origin and destination.

This exposure fluctuates in line with:

- prevailing diplomatic relations;

- disputes;

- and regional developments.

At present, however, the Iranian UAVs threat primarily extends to Israel-affiliated shipping.

To a lesser extent, other interests deemed a legitimate target by Tehran include those affiliated to:

- Belgium;

- Greece;

- Iraq;

- Israel;

- Japan;

- South Korea;

- UK (including Crown dependencies and overseas territories);

- US;

- and Saudi Arabia.

These nations’ assets have been targeted if they are involved in conflicts with Iran or its regional proxies, or if they are in debt to, or have diplomatic disputes with, Iran. One of the largest causes of any potential aggravation has been the financial sanctions imposed by the US upon Iran, which have caused Iraq, Japan, South Korea, and the UK to freeze Iranian accounts in their financial institutions. These disputes have yet to lead to UAVs assaults. These disputes have predominantly resulted in vessel seizures in the Gulf of Oman and Strait of Hormuz.

Attack Methodology

Iranian UAVs variants can be launched from land, either via a stationary launch pad or moving vehicle, and from sea. Iran has repurposed a merchant vessel to function as UAV-carriers comparable to aircraft carriers. UAVs can be launched from most Iranian Navy or IRGC Navy vessels.

Maritime targets have likely been surveilled through the tracking of the Automatic Identification System (AIS), with the UAVs being guided towards the target by a proximate operator. The guidance and control systems of some UAVs feature an auto-pilot function, which is able to transfer data to a ground station over a datalink. However, vessels withholding their AIS signal have been struck as well, indicating that the AIS data alone is not used to target vessels, and withholding it is merely a mitigating factor.

Attacks on maritime targets may be launched from a nearby vessel, which is likely to be in line of sight with the target and transmitting on encrypted satellite communications.

The guidance of some UAVs weapons is TV or optical. The operator is therefore required to get the UAV to a point where it can «see» the target in a narrow field of view, in a high-definition link that has a latency factor. The terminal behaviour of the UAV in flight, is a terminal ballistic dive; the threat axis is vertical. The Iranians have missed moving targets before, clipping vessels, and then sending follow-up UAVs.

The Houthi UAV Threat

The Houthi have launched hundreds of drone attacks into Saudi Arabia over the course of the Yemeni Civil War.

While the majority of these attacks have been aimed at provinces that border Yemen, there have been a number of incidents in which they have deliberately targeted airports, oil plants, and other key infrastructure situated deeper into the Kingdom. Notable attacks include those on Riyadh and the Aramco oil facilities, as well as ports on the western coast such as Jeddah or Jazan. On 30th July 2021, the day after the MERCER STREET attack, a UAVs struck a Bahamas-flagged and Greek-owned LR2/Aframax tanker, the ALBERTA, near Jazan, Saudi Arabia. On the same day, Saudi media condemned an attack by a UAV on a Saudi vessel in the southern Red Sea.

It is widely accepted that Iran covertly supplies UAVs parts and designs to the Houthis, as reported by the UN Panel of Experts (PoE). In 2019, the Houthis claimed that they have the capability to manufacture their own UAVs. Given the simple designs of the Qasef-1 and Samad-3 amongst others, it is likely that claims of indigenous production are true. It is possible to identify some differences over time in the capabilities of the Houthi UAV arsenal.

Before 2018, their UAVs were limited to an approximate 150 km range, meaning their attacks were confined to border regions and targets within Yemen. However, the UN uncovered a new model in mid-2018, the Samad-3, which could operate at a range of between 1 200 km to 1 500 km, greatly enhancing the capability of the fleet.

Since the non-renewal of the ceasefire in late 2022, the Houthis have prominently used UAVs to target south Yemeni port facilities in a successful bid to halt oil and gas exports by the Yemeni government. These incidents have led to collateral vessel damage and injured crew. However, no vessel was specifically targeted. The Houthis also remain to prove their capability to target moving vessels at sea. Given the Houthi’s ability to target vessels by other means and the resemblance of the Iranian and Houthi arsenal, it is assessed highly likely the Houthi possess this capability and their range enhancement was confirmed by the Houthi’s targeting of Eilat, Israel with a «large number» of ballistic missiles and drones launched in October 2023.

Drone Insight

Ambrey Analytics assesses that Shahed-136, Qasef-1, and Samad-3 are the three most likely UAVs to be used against merchant vessels, with the latter two being predominately operated by the Houthis.

The US Navy’s report on the attack on MERCER STREET in July 2021 states to a high degree of certainty that the drone used in the attack was a delta-winged Shahed-136.

See Shahed-136 reference see below.

Incident

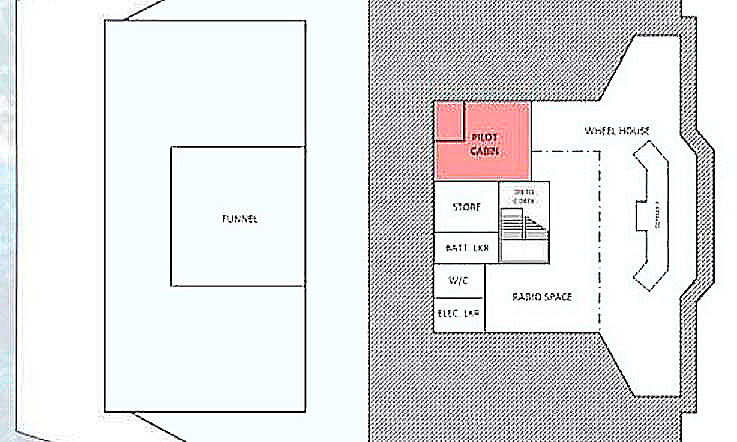

On the 19th of July 2021, the MERCER STREET’s pilot cabin was struck by a Shahed-136 while transiting northbound through the Arabian Sea, bound to enter the Gulf of Oman.

The impact of the UAVs killed the master and the team leader of a Private Armed Security Team onboard. The shockwaves of the impact could cause further injuries to crew in the vicinity. The vessel was Israel-affiliated and to date, only Israel-affiliated vessels have been targeted by Iran-launched UAVs, typically in a tit-for-tat style interaction following Israel damage to Iranian vessels or infrastructure.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

Single Rotor

Single rotor – these have a single main rotor and typically a smaller tail rotor. These have a large fuselage with a relatively narrow tail and have a helicopter-shaped silhouette.

Rotary wing systems can have one main rotor that sits on top of the fuselage and rotates on a horizontal plane, and usually have a smaller rotor fixed to the tail that rotates on a vertical plane. This is a typical helicopter-shape when seen from below.

Multi Rotor

Multi-rotor – the number of rotors can vary on these. The silhouette varies depending on number of rotors but essentially, they have a central fuselage with rotor arms protruding and the rotors on the end of each arm.

Rotary systems can also be multi-rotor, also known as multi-copter. They typically have 4, 6, or 8 rotors, but can have many more. The shape on these will vary depending on the size and number of rotors but they typically appear insect-like in shape as the rotors sit on the end of extended rotor arms that stick out from the fuselage and they have skids on the bottom for landing on hard surfaces.

Fixed Wing

Straight wing – the wings clearly protrude from the fuselage (body) of the craft. This forms a cross-shaped silhouette when viewed from below.

Fixed wings can be found with a relatively straight wing in which there’s clearly two main wings sticking out of the fuselage (or body), one on each side, supported by smaller wings usually at the tail but sometimes closer to the nose of the fuselage. When viewed from below, the wings are prominent, and they form a kind of cross-shape with the fuselage.

Delta Wing

«Delta» wing – the wings are not as distinguishable from the fuselage. This forms more of a triangle-shaped silhouette when viewed from below.

Fixed wings can also be found in a «delta» wing form. This looks more like one large wing rather than two that are clearly defined. The wing is usually identified from below as looking triangular in shape with the fuselage in the middle. Smaller alerions or vertical stabiliser wings can usually be seen at each end of the wing.

Drone Catalogue

Ambrey Intelligence assesses that «Wa’aed», Qasef-1, and Samad-3 are the three most likely UAV to be used against merchant vessels, with the latter two being predominately operated by the Houthis.

The US Navy’s report on the attack on MERCER STREET in July 2021 states to a high degree of certainty that the drone used in the attack was a delta-winged Shahed-136 referenced, below.

| SHAHED-136 – «KAMIMAZE DELTA WING» | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | up to 2 400 km, depending upon the engine used within the drone. A jet-powered version, Shahed-238, has been introduced, but not yet utilised. |

| PAYLOAD | 30/50 kg – however, MERCER STREET incident left traces of the nitrate based explosive RDX. Moreover, the blast and speed at impact was able to cause the damage to steel that is shown in the images below. |

| SIZE | 2,5 m wingspan and 3,5 m length. It caused an approximately 6ft hole in the pilot’s cabin of the MERCER STREET. |

| SOUND | Single engine and propellor. |

| PROFILE | Large nose carrying the explosive payload. Triangular-shaped body, two vertical fins attached next to rear ailerons. Engine and propellor fixed to the rear of the UAV. |

| PREVALENCE | This type of drone (or a version of it) is known to have been used in the 2019 attack on Aramco oil facilities in Saudi Arabia. The delta-wing body profile was first observed in Iranian military use within footage of military exercises undertaken in August 2020, January 2021, and again in May of that year. The US Navy have reported that this type of drone struck the MERCER STREET in July 2021. The Houthis unveiled the «Wa’aed» in March 2021, with this bearing very strong similarities to the Iranian drones and the descriptions given by the MERCER STREET report. |

| QASEF-1/ABABIL-T | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 150 km -200 km. |

| SPEED | 200 kph. |

| GUIDANCE | Pre-programmed GPS. Debris shows that this drone carries data link equipment. |

| PAYLOAD | 30 kg warhead, loitering munition. Known to be able to be detonated above targets while in flight. |

| SIZE | 2 m wingspan, launched by ground-assistance, be that a catapult or jet-assisted. |

| LAUNCH SITE | Can be both ground and sea-based. |

| SOUND | Single Chinese-made two-cylinder engine, powering sail propellor blades. Video footage of a Houthi attack upon a Yemeni military parade shows that the incoming drone became obviously audible from a minimum of 5 seconds before impact. |

| PROFILE | Virtually identical to the Ababil-2 (Ababil-T) UAV, containing parts known to have been shipped into Iran. Smaller horizontal stabilising wings near the nose of the drone and larger rear wings towards the rear of the drone. Two vertical stabilising fins attached to rear wings, with engine and propellor at the rear of the fuselage. Payload carried in the nose of the drone. |

| PREVALENCE | A UN PoE report to the Security Council stated that this drone has been used in Yemen from 2016. CAR reported in 2017 that these UAV were being built in Iran and then transported to the Houthis. |

| «GAZA» SHAHED-149 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 2 000 km, 35 hrs, 35 000 ft, 350 km/h. |

| PAYLOAD | Up to 13 explosive ordinances. |

| SIZE | 11 m long, 20 m wingspan, launching from a hard runway. |

| SOUND | Single engine. |

| PROFILE | Largest known UAV operated by Iran. V-shaped tail fins with air intake in-between. Nose and wings of similar profile to that of a US Predator. |

| PREVALENCE | Unveiled 21 May 2021 by the IRGC. |

| FOTROS | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 2 000 km, 25 000 ft, 30 hrs. |

| PAYLOAD | 4 Sadid air-surface missiles, laser-designator. |

| SIZE | 9 m long, launched by ground-assistance, be that a catapult or jet-assisted. |

| PROFILE | Bulged nose, long wingspan and twin rear wing. |

| PRELEVANCE | Unveiled in 2013, however, it is not known whether it has ever been operational. In 2020 it was announced that the IGRC would receive Fotros drones. |

| SHAHED-129 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 1 700 km, 24 hrs, 24 000 ft, 150 km/h. |

| PAYLOAD | Up to 8 explosive ordinances. |

| SIZE | 8 m long, 16 m wingspan, launching from a hard runway. |

| SOUND | Single engine and propellor. |

| PROFILE | Large V-shaped tail fins with a small air intake at the rear. The profile was recently updated to include the bulged nose, which was claimed to add improved navigation systems. |

| PREVELANCE | Since 2012. (Shahed 129 «Simorgh» is the naval version of this UAV, seen in blue below. This model was unveiled at Konarak, Iran). |

| MOHAJER-6 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 200 km, 12 hrs, 18 000 ft, 200 km/h. |

| PAYLOAD | 2 guided missiles. |

| SIZE | 5,4 m long, 10 m wingspan. Launched from a 400 m runway. |

| SOUND | Single engine and propellor. |

| PROFILE | Rectangular fuselage, upward sloping nose, twin tail booms and central propellor. |

| PREVALENCE | Believed to be operated by Iran from 2020. |

| «KIAN» KAMIKAZE | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 4 000 km. |

| PAYLOAD | Drone is the warhead itself. Believed to carry Tiam 1 400 anti-surveillance technology, aiming to jam radar signals. |

| SIZE | Approximately 2 m length. |

| SOUND | Jet sound on take-off, uses propellor in-flight. |

| PROFILE | «Missile» shaped with wings and tail fin. |

| PREVALENCE | «Kamikaze» drones first operated in Iranian military exercises in January 2021. |

| SAEGHEH-2 (SHAHED-191) | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 1 000 km, 300 km/h, 4,5 hrs, 25 000 ft. |

| PAYLOAD | 50 kg of explosive ordinance claimed. Has been seen armed with four Sadid-1 missiles, or just single bombs. |

| SIZE | Approximately 8-10 m wingspan, length of about 2 m. |

| SOUND | Jet-powered. |

| PROFILE | A smaller, reverse-engineered, copy of the delta-winged American RQ-170 Sentinel. |

| PREVALENCE | Believed to have been used in the attacks on the Abu Kamal region of Syria in 2018 and operated from the Shahid Karimi base near Kashan, Iran. |

| ABABIL-3 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 150 km. |

| PAYLOAD | Pictured carrying Ghaem guided munitions. |

| SIZE | 7 m wingspan. |

| SOUND | Propellor engine |

| PROFILE | Twin tail boom and tail fins, engine in the middle. |

| PREVALENCE | Revealed as an armed UAVs on 18 April 2020. Had previously been used as an unarmed surveillance drone. They are known to have been based at Bander Abbas, Iran, in the past. |

| SAMAD-3 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 1 200-1 500 km, 200-250 km/h. |

| GUIDANCE | Pre-programmed GPS. |

| PAYLOAD | 18 kg explosives mixed with ball bearings. |

| SIZE | 2,8 m length, 4,5 wingspan. |

| SOUND | Single 3W-110i B2 engine, manufactured in Germany then illegally shipped from Athens to Iran with the serial number removed. |

| PROFILE | One set of wings, central to the body of the drone with a wingspan nearly double the length of the fuselage. V-shaped tail fins mounted to the rear of the drone’s body. Payload carried in the nose of the UAV. |

| PREVALENCE | CAR reported in 2017 that these UAV were built in Iran and then transported to the Houthi. |

| SAMAD-4 | |

|---|---|

| RANGE | 2 000 km |

| PAYLOAD | 2 bombs weighing up to 25 kg each. |

| SIZE | 5 m wingspan, 3 m length. |

| SOUND | Propellor engine. |

| PROFILE | V-shaped tail fins with a third, vertical fin in the centre of the tail. Antenna attached to the nose. |

| PREVALENCE | Unveiled by the Houthis in March 2021, believed to have been supplied by Iran. |

Mitigation

AMBREY GUARDIAN is a best-in-class digitally supported Watchkeeper Service, designed to deliver operational support requirements and provide clients with an optimised and dynamic risk assessment, to keep risk at the lowest acceptable level wherever and whenever it is most needed.

We oversee every stage of the voyage – your vessel, its route and its proximity will be constanty monitored as it joins the largest risk managed fleet in the world.

AMBREY combines the world’s largest maritime team of operations managers, watchkeepers, in house thematic and geographical analysts with our 24/7-365 Global Operations Centre to deliver this unique service.

GUARDIAN proactively identifies your risk, informs you of optimal mitigation, and supports your operations to reduce risk.

Guardian Responds to Sentinel Alerts:

- SENTINEL Alerts visibility – global coverage of crime, war, activism, militancy, and migration.

- All alerts are sourced, verified, and streamed in real-time.

Pre-Voyage Service:

- Transit & Port Risk Assessments.

- Vessel Advised Routing.

- Dynamic BMP Checklist.

Live Voyage Monitoring:

- Global Operational Tracking.

- Over the Horizon Scanning.

- Real time Re-Routing.

- SENTINEL – Global Alerts Service.

- Crisis Management.

Immediate Actions

Update and test emergency practices. UAV can travel at incredible speeds, which is why readiness and posture, reaction times and reporting drills are absolutely vital to keeping crew safe.

- Do not let a UAV sighting go unreported.

- In the event of a UAV sighting, an alarm should be sounded.

- The alarm should be distinct from other types, and familiar to all crew members.

- In the event the UAV alarm is sounded, and the UAV is on a direct trajectory with the vessel, crew should take hard cover.

Where permitting, and if in doubt as to the UAV intention, crew should move directly to the UAV Safe Muster Point (SMP). The Master or OOW should activate the SSAS and either cut the engines or put the vessel into a permanent turn – this action needs to be decided by the Master as there are safety implications. Once at the SMP, communications must be established with UKMTO, the CSO, and any appointed intelligence partner.

Crew should stay at the SMP until instructed otherwise.

Safe Muster Point

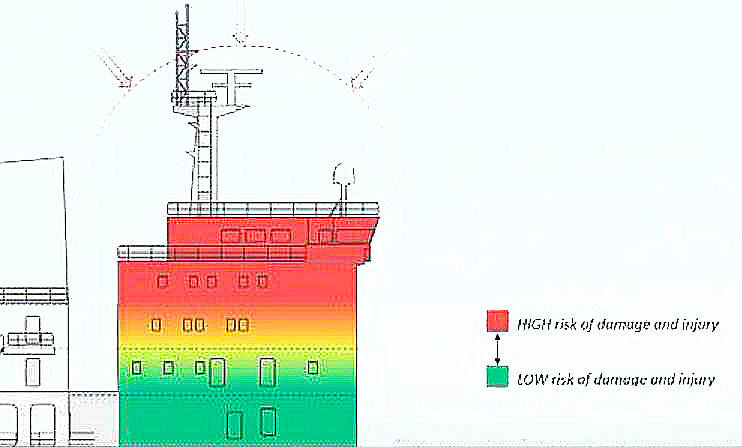

Careful consideration must be given to location of a UAV SMP.

- The UAV SMP location must be low-down in the superstructure, but above the waterline in case the vessel receives damage to the hull and takes on water.

- The closer to the potential point of impact, the higher the risk of significant damage and injury as a direct result of the explosion.

- As you increase the distance and the number of layers of protection between the potential point of impact and the muster point, the risk decreases.

This is illustrated in the coloured overlay on the diagram, above.

Mitigation

Actions on

If at any time a member of the security team or crew discover a UAV on the vessel, or an item dropped by a UAV, it should be treated as a suspected Improvised Explosive Device (IED). The team should implement and coordinate the «5 Cs», namely:

1 CONFIRM

From a safe distance (as far away as practicable), look for IED indicators and gather as much detail as possible about the device. NB if the device is on the deck and you are viewing from an elevated position, remember that the blast from an explosion will be directed upwards as well as outwards to the sides.

2 CLEAR

If confirmed as a suspected explosive device, evacuate the immediate area to a safe distance. The distance will be dictated by the layout of the vessel and the position of the potential IED.

3 CORDON

Ensure the area around the potential IED is put out of bounds to all onboard. Where possible, place a physical cordon 360° around the device and at a safe distance above if required.

4 COMMUNICATE

Inform the CSO and your appointed intelligence provider, giving as much information as possible about the device, including photographs.

5 CONTROL

Control the access to the area as much as possible. The crew onboard should all be made aware, and the cordon will help keep them away. If you have other vessels approaching to assist, ensure they are directed away from the device e. g. if the device is located on the main deck on the port side, ensure the approaching vessel is aware and direct them to the starboard side.

Bridge Manning

If the vessel is exposed to an increased level of risk to UAV attack on a particular voyage, or a particular passage of that voyage, manning levels on the bridge should be kept to a minimum for the duration of the increased risk.

Accommodation on the vessel must also be considered carefully. The pilot cabin is located on the Bridge deck on many vessels but if the vessel is exposed to an increased level of risk to UAV attack, it will be advisable to keep this cabin vacant. Anyone accommodated in this cabin is to be considered an additional person on the bridge deck.

Hardening

If the event of a UAV attack, most of the energy will be absorbed on first contact and will reduce significantly on each subsequent layer. Consideration should be given to the construction of each layer between the external wall and the designated UAV SMP – are they steel bulkhead or a lighter, weaker material? What is in the compartments adjacent to the UAV SMP? Is there anything in there that can affect the level of protection i. e. pressurised containers?

Consideration should be given to a side-on approach, and the number of layers of protection between potential point of impact. The principle remains that when you increase the distance and the number of layers of protection between potential point of impact and the UAV muster point, the risk decreases.

Stand-off bar/cage/slat solutions are available and could help mitigate risk to key areas.

Mitigation

Routing

The use of UAVs in direct attack is deliberate and intelligence-led. Avoid predictable routing behaviour. Adjust routing, even by small margins, and avoid contested waters and higher risk areas.

When trading through an at-risk area, consider exploitation of group convoy services and high-density traffic corridors to reduce the asset’s visibility and increase response times in the event of an incident.

The use of traffic separation schemes should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Similarly, exploitation of atmospherics – for example, deciding whether to trade during daylight or at night – should be cognisant of the prevailing threat in a given area.

When underway, consider selective use of AIS details by amending status and destination filters, but do not switch off AIS. Consider the appointment of a specialist tracking provider to exploit restricted SAT-Cservices available to the market. The use of AIS remains entirely at a Master’s discretion, but adjustments should be entered in the deck log. In the event of an incident, AIS should be switched on.

Note some authorities consider turning off AIS to be illegal and will seek to act, or at least board and investigate «non-compliance».

An AIS transmission gap is widely considered to be indicative of deceptive shipping practices, though may be explained by:

- poor satellite coverage;

- overcrowding;

- weather and GPS jamming.

Consider the frequency of AIS gaps is an indicator in differentiating between lost AIS signal and so-called «dark activity».

Note also AIS adjustments are used as an indicator – or red flag – by publicly available sanctions registries and may also result in challenges from charterers prior to fixing trade.

Compliance

Consider counter-party risks. Some sanctions with Iran remain in place. Consideration should be made as to whether the product traded is restricted, including how payments will be made. Recall that a commercial vessel’s exposure is primarily driven by its state affiliations through flag, ownership domicile and, to a lesser extent cargo origin and destination.

Screen for counter-party ownership history, as well as suspicious behaviour, including selected or obscured AIS history.

Reporting

All incidents or sightings, irrespective of whether they mature to hostile action or not, should be reported.

Appoint Ambrey Guardian services to source and secure lines of communication between the vessel and regional authorities best positioned to respond in the event of an incident. An initial report will allow authorities to expedite a response and enhance onward situational awareness. More detail can be added as soon as practicable.

At a minimum, the initial report should include:

- Vessel name and type of incident.

- Time of incident, position, heading, and speed.

- Brief description of damage and casualties (if any).

- What actions the team and crew are taking/have taken.