Women pirates have often been overshadowed by their male counterparts, but their impact on maritime history is significant. Figures such as Anne Bonny and Mary Read defied societal norms in the 18th century Caribbean, becoming infamous for their daring exploits. Both women disguised themselves as men and joined pirate crews, where they quickly gained notoriety for their bravery and ruthlessness. Their stories highlight not only their individual courage but also the broader role of women in pirate societies, which were often more egalitarian than contemporary land-based societies.

In addition to Bonny and Read, other notable women like Jeanne de Clisson and Ching Shih made their mark on pirate lore. Jeanne de Clisson, a French woman, turned to piracy after her husband was executed by the French government, leading a ruthless campaign against her enemies. Ching Shih, a Chinese pirate, commanded a vast fleet in the South China Sea, establishing a strict code of conduct for her crew and successfully negotiating a pardon that allowed her to retire comfortably. These women, among others, broke free from traditional gender roles, demonstrating that piracy offered opportunities for women to exercise power and influence in ways that were otherwise unavailable to them in their contemporary societies.

The harbor at Nassau is a long stretch of shimmering blue water which lies between the wharves lining the town’s waterfront and a low offshore island of sandy beaches and palm trees. Today the harbor welcomes cruise ships and visiting yachts, but in the eighteenth century it provided a sheltered anchorage for small trading vessels and the occasional man-of-war. It was also a well-known refuge and meeting place for pirates. On August 22, 1720, a dozen pirates rowed out to a single-masted sailing vessel which was anchored in the middle of the channel. The vessel was a twelve-ton sloop called the William, which was owned by a local man, Captain John Ham. She had four guns on her broad, sun-bleached decks, and two swivel guns mounted on her rails. She was well equipped with ammunition and spare gear, and had a canoe lying alongside which was used as a tender. The pirates climbed on board, heaved up the anchor, and set the sails. They were soon clear of the other vessels in the anchorage and heading out to sea in the stolen sloop. Thefts of this type were not uncommon in the Caribbean, but a keen-eyed observer might have noticed something about the pirate crew which was unusual. Although they were dressed in men’s jackets and long seamen’s trousers, two of the Review of Pirate Tactics in Ship Combatpirates were women.

The leader of the pirates was John Rackam, a bold and somewhat reckless character whose colorful clothes had earned him the nickname of Calico Jack. He was fond of women, and it was said that he kept a harem of mistresses on the coast of Cuba. He had been quartermaster in Captain Vane’s pirate company, but in November 1718 he had challenged his captain’s decision not to attack a French frigate in the Windward Passage. The crew branded Vane a coward and elected Rackam as captain in his place. Taking command of Vane’s ship, he proceeded to plunder a succession of small vessels in the seas around Jamaica. There is no record of Calico Jack using torture or murder, and he seems to have gone out of his way to treat his victims with restraint. When he had finished looting a Madeira ship, he returned the vessel to her master and arranged for Hosea Tisdale, a Jamaican tavern keeper, to be given a passage home. Compared to Bartholomew Roberts and Blackbeard, who commanded forty-gun warships and sailed into action with a flotilla of supporting vessels, Calico Jack was a small-time pirate. He preferred to operate with a modest sloop, and he restricted his attacks to small fishing boats and local trading ships. His chief claim to fame lay not in his exploits during his two years as a pirate captain but in his association with the female pirates Mary Read and Anne Bonny, whose lives were considerably more adventurous and interesting than his own.

Calico Jack met Anne Bonny in New Providence. He had sailed to the island in May 1719 to take advantage of the amnesty being offered by the Governor of the Bahamas. He accepted the royal pardon and for a while abandoned his life as a pirate. While frequenting the taverns on the waterfront at Nassau, he came across Anne Bonny and proceeded to court her in the same direct manner he used when attacking a ship: «no time wasted, straight up alongside, every gun brought to play, and the prize boarded». He persuaded her to abandon her sailor husband and took her to sea with him. When she became pregnant, he took her to his friends in Cuba, and there she had their child. As soon as she was up and about, Calico Jack sent for her and she rejoined his crew, dressed as usual in men’s clothes. He had taken up piracy again, and it was around this time that Mary Read joined his crew. She too was dressed as a man, and had been sailing on a merchant ship which he had captured. Anne Bonny found herself strongly attracted to the new member of the pirate crew, and in a quiet moment when they were alone she revealed herself as a woman. Mary Read, «knowing what she would be at, and being sensible of her own capacity in that way, was forced to come to a right understanding with her, and so to the great disappointment of Anne Bonny, she let her know that she was a woman also». To avoid any further misunderstandings, Calico Jack was let into the secret.

By the summer of 1720 they were all back in New Providence, and were evidently well known to the authorities there. When they stole the sloop William from Nassau harbor, the Governor had no doubt about their identities. On September 5 he issued a proclamation which set out the details of the sloop and gave the names of Rackam and his associates. The list included «two women, by name, Ann Fulford alias Bonny and Mary Read». The proclamation declared that «the said John Rackum and his said Company are hereby proclaimed Pirates and Enemies to the Crown of Great Britain, and are to be so treated and Deem’d by all his Majesty’s subjects».

The Governor of the Bahamas at this time was Captain Woodes Rogers, a tough and resolute seaman who had commanded a successful privateering voyage around the world from 1708 to 1711. He had come out to the West Indies in 1718 with a commission from the British government to rid the Bahamas of the pirate colony which was based on New Providence. He sailed into Nassau harbor with three warships and had made strenuous efforts to reestablish law and order. He had authority from King George to issue pardons to pirates who agreed to abandon their trade, and Calico Jack was one of many who did so. The new Governor was prepared to use harsh measures if the pardons failed to produce results. When some of the pardoned pirates returned to their old ways, he had them rounded up and hanged on the waterfront at Nassau beneath the ramparts of the fort.

Source: wikipedia.оrg

Woodes Rogers was equally decisive when he learned that the sloop William had been stolen from the harbor. As well as issuing the proclamation, he immediately dispatched a sloop with forty-five men to catch the pirates, and on September 2 he dispatched a second sloop armed with twelve guns and a crew of fifty-four men to join the chase. Calico Jack must have learned that vessels were out looking for him. After attacking seven fishing boats off Harbour Island in the Bahamas, he headed south. He intercepted two merchant sloops off the coast of Hispaniola on October 1, and two weeks later he took a schooner near Port Maria on the north coast of Jamaica. During the next three weeks the William cruised slowly westward, past the coves and sandy beaches of Ocho Rios, Falmouth, and Montego Bay, until she came to Negril Point at the extreme western tip of the island. There Calico Jack’s luck ran out.

Sailing in the vicinity was a heavily armed privateer sloop commanded by Captain Jonathan Barnet, «a brisk fellow», with a commission from the Governor of Jamaica to take pirates. Hearing a gun fired from Rackam’s anchored vessel, Barnet changed course to investigate. Alarmed by the appearance of Barnet’s powerful-looking vessel, Rackam hurriedly got under way. Barnet gave chase and caught up with the pirates at ten o’clock at night. He hailed them and received the reply «John Rackam from Cuba». Barnet thereupon ordered him to surrender, but the pirates shouted defiance and fired a swivel gun at Barnet’s ship. In the darkness it was difficult for either side to see its opponents clearly, but Barnet immediately retaliated with a broadside and a volley of small shot. The blast carried away the pirates’ boom, effectively disabling their vessel, and Barnet came alongside and boarded the pirate sloop. The only resistance came from Mary Read and Anne Bonny. They were armed with pistols and cutlasses and shouted and swore at everyone in sight, but they failed to rally their shipmates, who tamely surrendered. The next morning the pirates were put ashore at Davis’s Cove, a tiny inlet halfway between Negril and Lucea. They were delivered to Major Richard James, a militia officer, who assembled a guard and escorted them across the island to Spanish Town jail. On November 16, Calico Jack and the ten male members of his crew were tried for piracy; a few days later, on November 28, the Admiralty Court assembled again for the trial of the two female members of the pirate crew.

Mary Read and Anne Bonny never acquired the notoriety of Henry Morgan, Captain Kidd, or Blackbeard, but they have attracted more attention than many of the most successful and formidable pirate captains of history. This is partly due to the vivid description of their lives in Johnson’s General History of the Pirates, and partly due to the fact that they were the only women pirates of the great age of piracy that we know anything about. This has given them a mythic quality which has inspired several books, plays, and films, and has led to their inclusion in the writings of feminist historians as well as in books on transvestism and cross-dressing.

The problem with their story is the lack of documentation for their early lives. The printed record of their trial and brief references in the colonial documents and contemporary newspapers provide information about the last year or two of their lives, but for the rest we have to rely on Captain Johnson, who is usually accurate but rarely indicates the source of his information. And the story that he tells is almost too amazing to be true. As he himself says, their history is full of surprising turns and adventures, and «the odd incidents of their rambling lives are such, that some may be tempted to think the whole story no better than a novel or romance».

According to Johnson, Mary Read was born in England, the second child of a young mother whose husband went away to sea and never returned. Following her husband’s disappearance the young woman had an affair with another man and became pregnant, but she was so ashamed at the idea of giving birth to a bastard child that she went away into the country to stay with friends. Shortly before Mary was born, the elder child, who was a boy, died. The mother soon ran out of money and decided to approach her mother-in-law for help in providing for the child. She dressed Mary up as a boy so that she could pass her off as her son, and traveled up to London. The mother-in-law duly agreed to provide a Crown a week for the child’s maintenance.

Mary Read was brought up as a boy, and at the age of thirteen her mother secured her a post not as chambermaid but as a young footman to a French lady. She soon tired of this menial life, and «growing bold and strong, and having also a roving mind, she entered herself on board a man-of-war». She then went to Flanders and enlisted as a cadet in the army. She distinguished herself by her bravery in several military engagements, but fell in love with a Flemish soldier in her regiment. The soldier was delighted to find himself sharing a tent with a young woman, but Mary Read was not prepared to continue indefinitely as his mistress. When the campaign was over, the two lovers got married. They left the army and set up as proprietors of a public house near Breda called The Three Horse Shoes.

Unhappily, Mary’s husband died not long after the marriage, and when the Peace of Ryswick was signed in 1697, the soldiers went elsewhere and The Three Horse Shoes lost most of its trade. Mary Read had no option but to seek her fortune elsewhere. She dressed up as a man again, and after a spell in a foot regiment, she embarked on a ship bound for the West Indies. The ship was captured by pirates, and after further adventures she found herself on the ship commanded by Rackam with Anne Bonny among the crew.

Anne Bonny had also been brought up as a boy. She was born near Cork in Ireland, and was the illegitimate daughter of a lawyer. Her father separated from his wife following a quarrel: the wife was upset because she had discovered that her husband had been having an affair with the maid of the household; the husband was enraged when his wife accused the maid of stealing some silver spoons and had her sent to prison. The husband was so fond of the girl he had by the maid that he decided that she must come and live with him. To avoid a scandal, he dressed her up as a boy and pretended that he was training her up as a lawyer’s clerk.

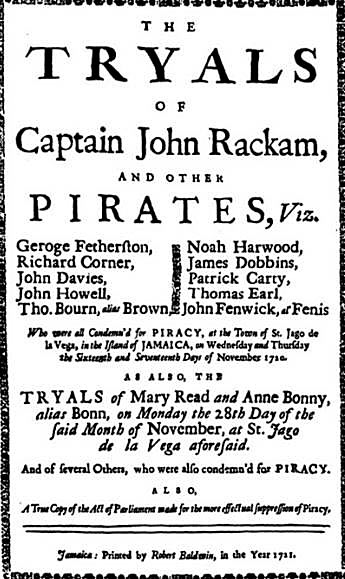

The lawyer’s wife discovered what was going on and stopped the allowance she had been giving him. The scandal affected his practice and he decided to go abroad. Taking the maid and their daughter, Anne, he sailed to Carolina, where he made enough money as a merchant to be able to purchase a plantation. Anne disappointed her father by falling for a penniless young seaman called Bonny and marrying him. Turned out of the house by her father, she and Bonny sailed to the island of Providence, where, as we have seen, she met Calico Jack, became a pirate, and after two adventurous years ended up in the courthouse in Jamaica alongside Mary Read. The printed transcript of the trial at Spanish Town provides firsthand information about some of Calico Jack’s exploits as well as descriptions of the appearance and behavior of Mary Read and Anne Bonny. The Admiralty Court that assembled on November 16 was presided over by Sir Nicholas Lawes, the Governor of Jamaica. There were twelve commissioners, two of whom were Royal Navy captains. The men on trial were Rackam himself, described as:

- «John Rackam, late of the island of Providence in America, mariner, late master and commander of a certain Pirate Sloop»;

- George Fetherston, also of Providence, «late Master of the said Sloop»;

- Richard Corner, the quartermaster;

- and John Davies, John Howell, Thomas Bourn, Noah Harwood, James Dobbins, Patrick Carty, Thomas Earl, and John Fenwick.

There were four charges against the prisoners:

1 That they «did piratically, feloniously, and in an hostile manner, attack, engage and take, seven certain fishing boats» and that they assaulted the fishermen and stole their fish and fishing tackle.

2 That they did «upon the high sea, in a certain place, distance about three leagues from the island of Hispaniola … set upon, shoot at, and take, two certain merchant sloops», and did assault James Dobbin and other mariners.

3 That on the high sea about five leagues from Port Maria Bay in the island of Jamaica they did shoot at and take a schooner commanded by Thomas Spenlow and put Spenlow and other mariners «in corporeal fear of their lives».

4 That about one league from Dry Harbour Bay, Jamaica, they did board and enter a merchant sloop called Mary, commanded by Thomas Dillon, and did steal and carry away the sloop and her tackle.

There were two witnesses for the prosecution. Thomas Spenlow of Port Royal, Jamaica, described how his schooner was fired on by the sloop manned by the prisoners at the bar. He said they «boarded him, and took him; and took out of the said schooner, fifty rolls of tobacco, and nine bags of piemento and kept him in their custody about forty-eight hours, and then let him and his schooner depart». The second witness was James Spatchears, mariner of Port Royal, who gave a detailed description of the action between the pirate sloop and the trading sloop commanded by Jonathan Barnet.

The prisoners pleaded not guilty to the charges, but all were found guilty and sentenced to death. Five were hanged the next day at Gallows Point, a windswept and featureless promontory on the narrow spit of land which leads out to Port Royal; the other six were hanged the next day in Kingston. Calico Jack’s body was put into an iron cage and hung from a gibbet on Deadman’s Cay, a small island within sight of Port Royal which is today called Rackam’s Cay.

The trial of Mary Read and Anne Bonny followed similar lines. The charges were exactly the same, but there were some additional witnesses for the prosecution, all of whom stressed that the female pirates were willing members of Rackam’s crew and took an active part in the attacks on merchant vessels. The most graphic description of their appearance was provided by Dorothy Thomas, who was in a canoe on the north coast of Jamaica when she was attacked by the pirate sloop:

… the two women, prisoners at the bar, were then on board the said sloop, and wore mens jackets, and long trousers, and handkerchiefs tied about their heads; and that each of them had a machet and pistol in their hands, and cursed and swore at the men, to murder the deponent; and that they should kill her, to prevent her coming against them; and the deponent further said, that the reason of her knowing and believing them to be women then was by the largeness of their breasts.

Two Frenchmen who were present when Rackam attacked Spenlow’s schooner explained with the aid of an interpreter how the women were very active on board, and that Anne Bonny handed gunpowder to the men; also, «that when they saw any vessel, gave chase, or attacked, they wore men’s clothes; and at other times, they wore women’s clothes».

Thomas Dillon, master of the sloop Mary, confirmed that both women were on board Rackam’s sloop when they made their attack. He said that «Ann Bonny, one of the prisoners at the bar, had a gun in her hand, that they were both very profligate, cursing and swearing much, and very ready and willing to do any thing on board».

When the women were asked whether they had anything to say in their defense, they both said they had no witnesses, nor did they have any questions to ask. The prisoners and all the onlookers were ordered to withdraw from the courtroom while Sir Nicholas Lawes and the twelve commissioners considered the evidence. It was unanimously agreed that the two women were guilty of the piracies and robberies in the third and fourth charges brought against them. They were brought back to the bar and told that they had both been found guilty. They could offer no reason why sentence of death should not be passed upon them, and so Sir Nicholas, in his role as president of the court, sentenced them with the time-honored words:

You Mary Read, and Anne Bonny, alias Bonn, are to go from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution; where you shall be severally hanged by the neck till you are severally dead. And God of his infinite mercy be merciful to both your souls.

For some reason the prisoners delayed their trump card until this moment; perhaps they did not believe they would be found guilty until they heard the president’s doom-laden words. But immediately after the judgment was pronounced, they informed the court that they were both pregnant. Unfortunately we do not know how this news was received by those present, but it must have caused something of a sensation. All we do know from the printed transcript of the trial is that the court ordered that «the said Sentence should be respited, and then an inspection should be made».

An examination proved that both women were indeed pregnant and they were reprieved. Unhappily, Mary Read contracted fever soon after the trial and died in prison. The Parish Register for the district of St. Catherine in Jamaica records her burial on April 28, 1721. It is not known for certain what happened to Anne Bonny or her child.

A separate trial was held on January 24, 1721, for nine unfortunate Englishmen who happened to be on board Rackam’s ship when it was captured by Jonathan Barnet. A few hours earlier they had been in a canoe looking for turtles, and had been persuaded to join the pirates for a bowl of punch. On the basis that they were armed and apparently helped Rackam to row his sloop, the court convicted them of piracy. Six of them were hanged, «which everybody must allow proved somewhat unlucky to the poor fellows», as Captain Johnson noted.

The story of Mary Read and Anne Bonny raises a number of questions. Was it so unusual for women to go to sea, and if so, why? Were there other women pirates? Was it essential for a woman to dress as a man if she wanted to join the crew of a ship? How was it possible for a woman to pass herself off as a man in the cramped and primitive conditions on board an eighteenth-century ship?

During recent years an increasing number of women have taken up sailing and have proved themselves able to handle large and small yachts in all weathers. Several women have sailed single-handed across the Atlantic and around the world, and all-women crews have competed successfully in ocean races. But for hundreds of years seafaring was an almost exclusively male preserve. While the fishermen heaved in their nets and lines in the icy waters off Cape Cod or the Dogger Bank, their wives and daughters remained behind to look after the young children, to make and mend the nets, and to pray that the men survived the storms. All too often there were tragedies. In 1848 a gale blew up during the night of August 18 and swept across the seas off Scotland. The fishing fleets from the various harbors around the coast had put to sea that afternoon and were caught unawares. As the wind built up into a raging southeasterly gale, the men hauled up their nets and ran for shelter. At Wick the fishermen’s families hurried down to the harbor and watched aghast as the boats battled against the foaming seas sweeping across the harbor entrance. Some boats were swamped and foundered on the harbor bar, some were smashed against the piers, and some were overwhelmed by the waves and sank offshore. Forty-one boats were lost, twenty-five men were drowned before the eyes of their relatives, and twelve were lost at sea. Seventeen widows and sixty children were left destitute. At Peterhead thirty-one men perished, and nineteen men from Stonehaven lost their lives in that summer gale.

Life in the navy and the merchant service was equally dangerous. Their larger ships were better able to ride out storms than the open fishing boats, but they were at the mercy of uncharted shoals, poor navigation, and death from scurvy and tropical diseases. Apart from the dangers of life at sea, there were the long absences from home: it was not unusual for a seaman to say good-bye to his family and not see them again for months and sometimes years. When Edward Barlow sailed from England in the Cadiz Merchant in September 1678 on a routine trading voyage to the Mediterranean, it was fifteen months before he returned to London.16 In the 1770s Nicholas Pocock made several voyages to the West Indies as captain of a small merchant ship; his trips from Bristol to the island of Dominica and back home took on average nine months. A seaman in the Royal Navy whose ship was sent to patrol the seas off Boston or the west coast of Africa might not see his home port for two years.

The dangers, the privations, and the absences from home did not discourage young men from going to sea, but in the days of sail it was unthinkable that women should be subjected to the physical demands of life on deck, and the wet, cramped, and foul-smelling conditions below. There was a widespread belief that a woman on board was likely to provoke jealousies and conflicts among the crew, and there was a tradition among seamen that a woman on a ship brought bad luck. In spite of all this, a surprising number of women did go to sea. Many traveled as passengers, of course, a few captains took their wives to sea with them, and there were instances when captains and officers smuggled their mistresses aboard. But there are also well-documented cases of women going to sea as sailors. Indeed, the history of the Royal Navy and the merchant service is littered with examples of women who successfully dressed as men and worked alongside them for years on end without being discovered. The life of Mary Anne Talbot has a number of parallels with that of Mary Read: she was illegitimate, she was dressed as a boy when she was young, and she spent part of her life as a soldier and part as a sailor. She was born on February 2, 1778, one of the sixteen bastard children of Lord William Talbot. She was seduced by her guardian, Captain Essex Bowen, who enlisted her as a young footman in his regiment. She sailed with him from Falmouth on the ship called Crown bound for Santo Domingo. She was present at the British capture of Valenciennes in July 1793, and some months later joined the crew of HMS Brunswick, where she served as cabin boy to her commander, Captain John Harvey. She was present at the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794, and was one of the few to survive the murderous action against the French ship Vengeur. She was, however, wounded by grapeshot and was sent to the naval hospital at Haslar. By 1800 she had left the navy and spent some time on the stage at Drury Lane before becoming a servant to a London publisher, R. S. Kirby, who wrote an account of her life which was published in 1804.

Hannah Snell went to sea in 1745 to look for her husband, a Dutch sailor called James Summs who had abandoned her when she was six months pregnant. She served for a time on the British sloop HMS Swallow, commanded by Captain Rosier, and took part in the siege of Pondicherry in 1748. Marianne Rebecca Johnson served four years in a British collier Mayflower without her sex being detected, and her mother spent seven years in the Royal Navy before being mortally wounded at the Battle of Copenhagen.

These and other women were able to survive in a man’s world by proving themselves as capable as the men in battle and in their duties as seamen. Mary Anne Arnold worked as an able seaman on the ship Robert Small until she was unmasked by Captain Scott, who became suspicious of her during the ritual shaving ceremony when crossing the line. He later declared that she was the best sailor on his ship and wrote, «I have seen Miss Arnold among the first aloft to reef the mizen-top-gallant sail during a heavy gale in the Bay of Biscay». Whenever Hannah Snell was challenged for not being sufficiently masculine, she always retaliated by offering to beat her challenger at any shipboard task. Mary Anne Talbot adopted male habits and in later life was accused of having «masculine propensities more than became a female such as smoking, drinking grog, etc.»

But how did these women manage to disguise their physical appearance and prevent their shipmates’ discovering their sex? Clearly the determination and ingenuity of the women who succeeded in fooling their shipmates was extraordinary. There was little privacy on board ship in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, though there were many dark corners in the badly lit areas belowdecks where a woman might have hidden her nakedness when necessary. Conditions on a ship in those days were very different from those on a modern vessel. Most people who travel on ships today expect them to be clean and shiny, with stainless steel fittings, running water in the taps, flush toilets, and comfortable bunk beds. An oceangoing merchantman in the eighteenth century was almost entirely constructed of wood, and was a confusing jumble of:

- tarred rope;

- mildewed sails;

- spare masts and spars;

- muddy anchor cable, hen coops;

- hammocks;

- seamen’s chests;

- wooden crates of various sizes;

- and numerous barrels containing water, beer, salt pork, and gunpowder.

In order to provide fresh meat and milk during the voyage, an assorted collection of cows, goats, ducks, geese, and chickens were kept in pens belowdecks. In fine weather the goats were often allowed to wander around on deck. Many of the seamen kept pets: dogs and cats were common, and so were parrots and monkeys.

In addition to the domestic animals and pets, merchant ships and naval ships often had a number of small boys on board who had been sent to sea to learn the ropes, and many of the most active members of the crew were boys in their teens. Dressed in the loose trousers, loose shirts, and jackets of the seamen, with a scarf or handkerchief around her neck, a strong young woman with a good head for heights would not have found it difficult to pass as a teenage boy when working on deck or up among the rigging. Belowdecks, amid the cargo and the animals and the smells of bilge water, manure, decaying wood, and tarred hemp, it would have been more difficult but not impossible for a woman to hide her sex, although she would have had to use some ingenuity to cope with the toilet facilities, which on most ships were extremely primitive. The seamen either climbed onto the leeward channels (platforms along the ship’s side for spreading the rigging) and urinated into the sea, or went forward to the beakhead or «heads». On the wooden structure overhanging the bows of the ship would be two or three boxes with holes in them. The seamen sat on the boxes, or «seats of easement» as they were called, and defecated through the hole into the water below. On smaller ships without a beakhead, the heads were inboard and the waste was discharged through a pipe in the ship’s side.

Life on a pirate ship was similar to life on a merchantman, partly because most pirate ships were former merchant ships with a few more guns added, and partly because the majority of pirates were former merchant seamen. Pirate ships usually had bigger crews and the men adopted a more relaxed regime, but their habits and prejudices were similar, and most pirates had the seaman’s traditional prejudice against taking women to sea. Article Three of the pirate code drawn up by Bartholomew Roberts and his crew stated that no boy or woman was to be allowed among them. «If any man were found seducing any of the latter sex, and carry’d her to sea, disguised, he was to suffer death». Captain Johnson’s explanation of this rule was that it was to prevent divisions and quarrels among the crew.

Many Typical Activities Aboard the Pirate Ship, the Pirate Codepirate captains preferred to take on men who were unmarried. It is difficult to obtain hard evidence on the numbers of pirates who were married, but one study of the Anglo-American pirates active in the years 1716 to 1726 shows that 23 pirates out of a sample of 521 are known to have married. That is around 4 percent, a remarkably small proportion of the total until one remembers that most pirates were young men in their twenties and therefore had not reached an age when they wanted to settle down. When Sam Bellamy’s pirate ship and her consorts were wrecked on the coast of Cape Cod, there were eight survivors. They were interrogated on the orders of the Governor of Massachusetts in May 1717, and their confessions indicate that married men were not welcome on Bellamy’s ships. Thomas Baker said that when he and nine other men were taken by the pirates off Cape François, the other men «were sent away being married men». Peter Hoof stated that «No married men were forced», which means they were not compelled to sign the pirates’ articles and join the crew. Thomas South confirmed that when his ship was captured, «The pirates forced such as were unmarried, being four in number».

When Philip Ashton was captured by pirates in the harbor of Port Rossaway in June 1722, the first ordeal he had to face was an interrogation by Edward Low, the pirate captain. Brandishing a pistol, Low demanded to know whether Ashton, and the five men captured with him, were married men. None of them replied, which so enraged Low that he came up to Ashton, clapped a pistol to his head, and cried out, «You Dog! Why don’t you answer me?» and swore vehemently that he would shoot Ashton through the head if he did not tell him immediately whether he was married or not. When he learned that none of them were married, Low calmed down. Ashton subsequently learned that Low’s wife had died shortly before he became a pirate. She had left a young child in Boston that Low was so fond of that he would sometimes sit down and weep at the thought of it. It was Ashton’s conclusion that this was the reason why Low would only take unmarried men, «that he might have none with him under the influence of such powerful attractives as a wife and children, lest they should grow uneasy in his service, and have an inclination to desert him, and return home for the sake of their families».

Some pirates did abandon their roving lives and settle down. When Howell Davis visited the Cape Verde Islands to carry out repairs to his ship, he left five of his crew behind when he sailed because they were so charmed with the women of the place: «one of them, whose name was Charles Franklin, a Monmouthshire man, married and settled himself, and lives there to this day». In the Public Record Office in London is a petition which was sent to Queen Anne in 1709 from the wives and other relations «of the Pirates and Buccaneers of Madagascar and elsewhere in the East and West Indies». It is signed by forty-seven women and is a plea for a royal pardon for all the offenses committed by the pirates. The petition was brought to the attention of the Council of Trade and Plantations. Lord Morton and others were in favor of a royal pardon as the only effective way of breaking up the pirate settlements in Madagascar, but it was not till 1717 that the pardon, or «Act of Grace», was issued, and by that time the pirate colony on Madagascar was in decline.

As far as can be gleaned from the meager information on the subject, very few of the pirate captains had wives and families. Henry Morgan was married but had no children. Captain Kidd had a wife and two daughters who lived in New York. Thomas Tew was married and also had two daughters. According to Captain Johnson, Blackbeard married a young girl of sixteen in North Carolina; she was reputed to be his fourteenth wife and apparently it was his custom after he had lain with her all night «to invite five or six of his brutal companions to come ashore, and he would force her to prostitute herself to them all, one after another, before his face». While this seems entirely in character, it might equally well be a flight of fancy on the part of Johnson. Reporting one of Blackbeard’s raids in January 1718, Governor Hamilton simply noted that «This Teach it’s said has a wife and children in London». None of the other pirate captains mentioned in Johnson’s History are recorded as being married.

Although a surprising number of women seem to have gone to sea on merchant ships or joined the navy disguised as men, very few women became pirates. Apart from Mary Read and Anne Bonny, the only female pirates mentioned in any of the pirate histories are the Scandinavian pirate Alwilda, the Irishwoman Grace O’Malley, and the Chinese pirate leader Mrs. Cheng.

Very little is known about Alwilda. She was the daughter of a Scandinavian king in the fifth century A. D. Her father had arranged for her to marry Prince Alf, the son of Sygarus, the King of Denmark, but she was so opposed to the marriage that she and some of her female companions dressed up as men, found a suitable vessel, and sailed away. The story goes that they came across a company of pirates who were bemoaning the recent loss of their captain. The pirates were so impressed by the regal air of Alwilda that they unanimously elected her as their leader. Under her command the pirates became such a formidable force in the Baltic that Prince Alf was dispatched to hunt them down. Their ships met in the Gulf of Finland, and a fierce battle took place during which Prince Alf and his men boarded the pirate vessel, killed most of the crew, and took Alwilda prisoner. Full of admiration for the Prince’s fighting qualities, Alwilda changed her mind about him and was persuaded to accept his hand in marriage. They were married on board his ship, and she eventually became Queen of Denmark.

While the story of Alwilda has a legendary air about it, the history of Grace O’Malley is well documented. There are several references to her in the State Papers of Ireland, and recent research has uncovered the main events in her life and shown that behind the heroine of the Irish ballads was a commanding woman, «famous for her stoutness of courage and person, and for sundry exploits done by her at sea». Grace O’Malley was born around 1530 in Connaught on the west coast of Ireland. Her father was a local chieftain and the descendant of an ancient Irish family which for centuries had ruled the area around Clew Bay. The O’Malleys had castles at Belclare and on Clare Island, and maintained a fleet of ships which were used for fishing, trading, and piratical raids on the surrounding territories. It seems likely that Grace went to sea as a girl, and it is said that she acquired her nickname «Granuaille» (which means «bald») because she cut her hair short like the boys she sailed with. In 1546, when she was about sixteen, Grace was married to Donal O’Flaherty and moved to her husband’s castle at Bunowen some 30 miles south along the coast. All that is known about this phase of her life is that Grace had three children and that after a few years of marriage her husband died, possibly murdered in a revenge attack. Grace returned to her father’s domain and took command of the O’Malley fleet. She was by now beginning to build up a reputation as a bold and fearless sea captain. In 1566 she married Richard Burke, another local chieftain, and moved to Rockfleet Castle in County Mayo. This became the base for her seafaring operations and was her home for the remaining 37 years of her life.

Rockfleet Castle still stands today on an inlet overlooking Clew Bay. It is a simple, square structure but is massively built of stone and stands four stories high above the surrounding moors. This wet and windswept stretch of the Irish coast makes a startling contrast with the pirate strongholds in the Bahamas. Both locations have beaches and bays and numerous offshore islands, but instead of palm trees rustling under the tropical sun, Rockfleet Castle stands among rolling hills covered with heather and bracken. While the heat of Nassau is cooled by fresh breezes in the evening, the gray waters of Galway and Connemara are swept by southwesterly gales blowing in from the Atlantic. But Clew Bay provided a secure anchorage for the O’Malley fleet, which in the time of Grace O’Malley consisted of around twenty vessels. All the documentary references indicate that several of these vessels were galleys, apparently the only vessels of this type on the Irish coast. Captain Plessington of HMS Tremontaney described an encounter with one of these vessels in 1601. «This galley comes out of Connaught, and belongs to Grany O’Malley», he wrote. He noted that the vessel «rowed with thirty oars, and had on board, ready to defend her, 100 good shot, which entertained skirmish with my boat at most an hour». Some years earlier Sir Henry Sydney, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, reported to Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s secretary: «There came to me also a most famous feminine sea captain called Grany Imallye, and offered her services unto me, wheresoever I would command her, with three galleys and 200 fighting men». In theory an oared galley, a vessel developed to deal with the calms in the Mediterranean, was wholly unsuitable for the turbulent seas around the British Isles, and presumably the oars were only used in light winds or for raids in sheltered coastal waters. At other times the galleys, like the Viking longships, must have shipped their oars and relied on a single square sail for their motive power.

The nature of Grace O’Malley’s piracy was determined by local circumstances. Although all Ireland was then part of the British kingdom ruled by Queen Elizabeth I, the government of each province was in the hands of a Governor appointed by the Queen. These Governors were usually English aristocrats or soldiers, and in Connaught they exerted an oppressive regime which led to constant rebellions from the local chieftains. Sometimes Grace led punitive raids against other chieftains, and sometimes she attacked and plundered passing merchant ships. In the 1570s her attacks provoked a storm of protest from the merchants of Galway and compelled Sir Edward Fitton, the Governor, to send an expedition against her. In March 1574 a fleet led by Captain William Martin sailed into Clew Bay and laid siege to Rockfleet Castle. Grace marshaled her forces and within a few days turned the tables on Martin and forced him to beat a retreat. But in 1577, during a plundering raid on the lands of the Earl of Desmond, she was captured and imprisoned in Limerick jail for eighteen months. She was described by Lord Justice Drury as «a woman that hath … been a great spoiler, and chief commander and director of thieves and murderers at sea to spoil this province».

Source: wikipedia.оrg

When Grace O’Malley’s husband died in 1583, she found herself in a precarious position. She was vulnerable to raids from neighboring chieftains, and in financial hardship because, according to Irish custom, a widow had no right to her husband’s lands. Believing that the best means of defense was attack, she launched a number of raids on the surrounding territories but incurred the hostility of Sir Richard Bingham, who had succeeded Fitton as Governor of the province. Bingham regarded her as a rebel and a traitor and sent a powerful force to Clew Bay which impounded her fleet. She felt her only recourse was to appeal to the Queen of England. In July 1593 a letter was received in London addressed to the Queen from «your loyal and faithful subject Grany Ne Mailly of Connaught in your Highness realm of Ireland». Grace explained that she had been forced to conduct a warlike campaign on land and sea to defend her territory from aggressive neighbors. She asked the Queen «to grant her some reasonable maintenance for the little time she has to live» and promised that in return she would «invade with sword and fire all your highness enemies, wheresoever they are or shall be». While the Queen’s advisers were looking into the matter, Grace O’Malley’s son was arrested by Bingham on charges of inciting rebellion. Grace decided that she must go to London and make a personal appeal to the Queen.

The Irish ballads have made much of her voyage across the Irish Sea and her audience with Queen Elizabeth:

«Twas not her garb that caught the gazer’s eye Tho’ strange, ’twas rich, and after its fashion, good But the wild grandeur of her mien erect and high Before the English Queen she dauntless stood And none her bearing there could scorn as rude She seemed well used to power, as one that hath Dominion over men of savage mood And dared the tempest in its midnight wrath And thro’ opposing billows cleft her fearless path».

In fact no details exist of the voyage or what was said at their meeting. All we know is that they met at Greenwich Palace in September 1593, and a few days later the Queen sent a letter to Sir Richard Bingham ordering him to sort out «some maintenance for the rest of her living of her old years». Bingham released her son from prison but continued to detain her ships and to harass her territories. However, in 1597 Bingham was succeeded by Sir Conyers Clifford and the O’Malley fleet was able to put to sea again. Grace was now nearly seventy years old and seems to have left it to her sons to run her fleet and defend the O’Malley lands. She died around 1603 at Rockfleet. Her son Tibbot proved a loyal subject and carried out Grace’s promise to fight the Queen’s enemies. In 1627 he was created Viscount Mayo.

Read also: Review of Traditional Pirates Food and Drinks

Grace O’Malley stands out as an isolated example in her time of a woman who took command of ships and armed forces, and proved able to survive as a leader in a hostile environment ruled by warlike men. Aside from military commanders such as Boadicea and Joan of Arc, one of the few women to match her achievement was the Chinese pirate Mrs. Cheng, whose fleets of junks ruled the South China Sea in the early years of the nineteenth century. Her full name was Cheng I Sao, which means «wife of Cheng I», but she is often referred to as Ching Yih Saou, or Ching Shih.

The customs, traditions, and way of life of the Chinese have for centuries been very different from those in the West. In the ports and along the rivers of southern China, entire communities lived and worked on the boats. In these floating villages the women played an active role in handling the sailing junks and small boats, and worked alongside the men when fishing and trading. The same conditions prevailed in the pirate communities. English observers such as Lieutenant Glasspoole noted that the pirates had no settled residences onshore but lived constantly on their vessels, which «are filled with their families, men, women and children». It was not unusual for women to command the junks and to sail them into battle. The Chinese historian Yuan Yung-lun described a pirate action which took place in 1809: «There was a pirate’s wife in one of the boats, holding so fast by the helm that she could scarcely be taken away. Having two cutlasses, she desperately defended herself, and wounded some soldiers; but on being wounded by a musket- ball, she fell back into the vessel and was taken prisoner».

Against this background it was not so surprising that a woman should assume leadership of a pirate community, particularly as there was a long tradition in China of women rising to power through marriage. Mrs. Cheng was a former prostitute from Canton who married the pirate leader Cheng I in 1801. Between them they created a confederation which at its height included some fifty thousand pirates. By 1805 the pirates totally dominated the coastal waters of southern China. They attacked fishing craft and cargo vessels as well as the oceangoing junks returning from Batavia and Malaysia. They lived off the provisions and equipment which they plundered at sea, and when these supplies proved insufficient they went ashore and looted coastal villages. They frequently ransomed the ships which they captured, and they ran a protection racket in the area around Canton and the delta of the Pearl River.

When Cheng I died in 1807, his wife moved adroitly to take over command. She secured the support of the most influential of her husband’s relatives, and she appointed Chang Pao as commander of the Red Flag Fleet, which was the most powerful of the various fleets in the confederation. This was a particularly shrewd move. Chang Pao was a fisherman’s son who had been captured by her husband and proved himself a brilliant pirate leader. He commanded respect among the ranks of the pirates and had become the adopted son of Cheng I. Within weeks of her husband’s death, Mrs. Cheng had also initiated a sexual relationship with Chang Pao, and several years later she married him. Henceforth Mrs. Cheng acted as commander in chief of the pirate confederation, with Chang Pao in charge of day-to-day operations. Between them they laid down a strict code of conduct, with punishments even harsher than the codes adopted by the pirates who operated in the West Indies in the 1720s. The punishment for disobeying an order or for stealing from the common treasure or public fund was death by beheading. For deserting or going absent without leave a man would have his ears cut off. For concealing or holding back plundered goods the offender would be whipped. If the offense was repeated, he would suffer death. The rules were equally strict over the treatment of women prisoners. The rape of a female captive was punishable by death. If it was found that the woman had agreed to have sex with her captor, the man was beheaded and the woman was thrown overboard with a weight attached to her legs.

For three years Mrs. Cheng and Chang Pao fought off all attempts by government forces to destroy the pirate fleets. In January 1808 General Li-Ch’ang-keng, the provincial commander in chief of Chekiang, led an attack on the pirates in Kwangtung waters. A fierce and bloody action took place during the night, and at one point Li sent in fire vessels. The result was an overwhelming victory for the pirates. Li was killed by pirate gunfire which tore out his throat. Fifteen of his junks were destroyed and most of the remainder were captured. Later that year Chang Pao advanced up the Pearl River and threatened the city of Canton. Attempts were made to starve out the pirates by cutting their supply lines, but this simply led to the pirates going ashore and looting the villages. Every naval force sent out to intercept the pirates was defeated, and by the end of 1808 the authorities had lost sixty-three vessels. Some of the local communities constructed barricades and formed militia units which managed to repel pirate raids: they would lure pirates into ambushes and pelt them with tiles and stones and buckets of lime. All too often the pirates swept aside the amateur forces and took a terrible revenge. At the village of Sanshan in August 1809 the pirates burned the place to the ground, beheaded eighty villagers, and hung their heads on a banyan tree near the shore. The women and children who had been hiding in the village temple were carried off by the pirates. When Chang Pao attacked the island of Tao-chiao in September 1809, his pirates killed a thousand of the islanders and abducted twenty of the women.

The sheer numbers involved in some of these pirate attacks make the activities of the pirates in the West Indies pale into insignificance. Sometimes Mrs. Cheng’s forces went into action with several hundred vessels and up to two thousand pirates. At the height of its power in 1809 the confederation’s fleet was larger than the navy of many countries. There were some two hundred oceangoing junks, each armed with twenty to thirty cannon and able to carry up to four hundred pirates. There were between six and eight hundred coastal vessels armed with twelve to twenty-five guns and carrying two hundred men. And there were dozens of small river junks which were manned by crews of twenty to thirty men. These vessels had sails and up to twenty oars, and were used for going up shallow rivers to plunder villages or to destroy farms when local communities had failed to pay protection money.

Mrs. Cheng’s reign as a pirate leader came to an end in 1810. Chinese officials had enlisted the assistance of Portuguese and British warships, and increasingly large forces were being assembled to counter the pirates. When the Chinese government offered an amnesty to the pirates, Mrs. Cheng resolved to take the initiative and secure the best possible terms. She decided to go unarmed to the Governor-General in Canton, and on April 18, 1810, she arrived at his residence with a delegation of seventeen women and children. It was a bold move and proved entirely successful. She was negotiating from a position of strength because the Governor-General and his advisers were only too aware of the terrible damage and casualties which her pirate squadrons were capable of inflicting. It was agreed that the pirates would surrender their junks and their weapons, but in return they would be able to keep their plunder and those who were willing were allowed to join the army. Mrs. Cheng also negotiated that her lieutenant and lover, Chang Pao, be given the rank of lieutenant and allowed to keep a private fleet of twenty junks. On April 20 no less than 17,318 pirates formally surrendered and 226 junks were handed over to the authorities. Not all the pirates got off scot-free: 60 were banished for two years, 151 were permanently exiled, and 126 were executed.

Mrs. Cheng and Chang Pao settled in Canton but later moved to Fukien, where they had a son. Chang Pao eventually rose to the rank of colonel and died in 1822 at the age of thirty-six. Mrs. Cheng, who was a wealthy woman, returned to Canton. She kept a gambling house but led a peaceful life and died in 1844 at the age of sixty-nine. It is a pity that there are no authentic descriptions of Mrs. Cheng’s appearance or character. The exploits and battles of the pirate confederation are recorded in detail in Chinese documents, but she herself remains a shadowy figure. She was evidently a resourceful and powerful woman. Whether she justifies the claim of one historian that she was «the greatest pirate, male or female, in all history» is questionable, but for three years she controlled and masterminded the activities of one of the largest pirate communities there has ever been.