Delve into the intricacies of below deck sail boat systems with this complete guide. Explore ventilation, marine heads, water systems, stoves and heaters, iceboxes and refrigerators, accommodations, and interiors for a comfortable and efficient sailing experience.

On any boat with accommodations, it is the belowdecks systems that make living aboard (even if only for a weekend) possible. With proper design, installation and maintenance, they can be serviceable and even provide some conveniences and comforts. With poor design, installation or maintenance, they can be an aggravation and can create some interesting character-building situations. In some instances, belowdecks problems can increase the risk of damage to the boat or even personal injury.

Keep in mind when assessing any of these systems that your needs in this area are highly dependent upon how the boat will be used and the size and type of boat that you ultimately select.

For example, the day sailer may only need a bucket for a head, while the marina live-aboard may require a sophisticated sewage treatment system. The weekender on a small pocket cruiser can easily adjust to using a small, single-burner alcohol or kerosene stove, while the serious coastal cruiser on a thirty- to forty-foot boat may find that only a large diesel stove and oven will meet cooking and auxiliary heat requirements.

Ventilation

Every boat should have extensive ventilation. Too much ventilation is rare except in below-freezing weather. In hot weather, adequate ventilation vents heat out of the boat and brings in cool air.

At any temperature, good ventilation helps eliminate the all-pervasive dampness of the marine environment and the moisture created by breathing, cooking, and heating in a closed space. Good air turnover is also important to prevent oxygen depletion and pollutant buildup from unvented or poorly functioning stoves and heaters.

Source: wikipedia.org

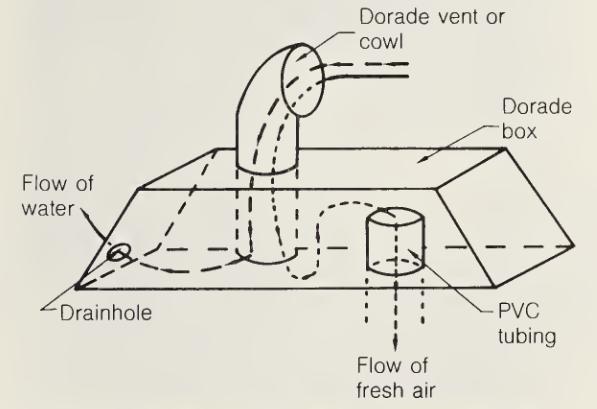

To facilitate ventilation, boats should have a number of opening hatches, opening ports, and dorade vents. Dorade vents should generally be installed on dorade boxes or with water traps, so that rain and seawater will be prevented from coming below.

Vents or dorades in both the bow and the stern greatly improve air circulation since the natural flow of air on a boat is from the stern to the bow. Provision should be made for complete sealing and securing of all hatches, ports, vents, and dorades in heavy weather.

Source: wikipedia.org

Inside the boat, air should be allowed to circulate freely within all the cabins and storage spaces. There should be vent holes and louvers in all drawers, doors, bins, and lockers. When a boat is closed up for any length of time, it is important to open all the drawers, doors, hatches, and icebox lids to ensure good air circulation.

Signs of poor air circulation and ventilation include stale, musty air, mold, drawers and doors that stick, condensation, and rot. Poor ventilation is death to a wooden boat.

Marine Heads

Waste discharge is regulated at the federal level, as well as by some state and local jurisdictions. The following is a brief summary of several options currently available. Compliance with applicable law should be checked when you consider any particular marine head system.

The traditional cedar bucket (or its modern counterpart in plastic) is probably the only practical alternative for a small boat. Its advantages are minimal cost, ease of installation, maintenance-free simplicity, and no through-hull fittings. Its major disadvantage is its low capacity, and emptying it several times a day may be distasteful.

A Porta Potty is a self-contained, no-discharge system.

After learning that this was the alternative used by our local Coast Guard commandant in 1977, we installed a $100 Porta Potty on our boat and used it almost trouble free for five years. Porta Potty advantages are low initial cost, simplicity, reliability, ease of installation, and no through-hull fittings.

Disadvantages include low capacity (usually three to six gallons), the difficulty of finding a dumping station (marinas aren’t enthusiastic about dumping in their toilets), the distastefulness of emptying them, and possible odors.

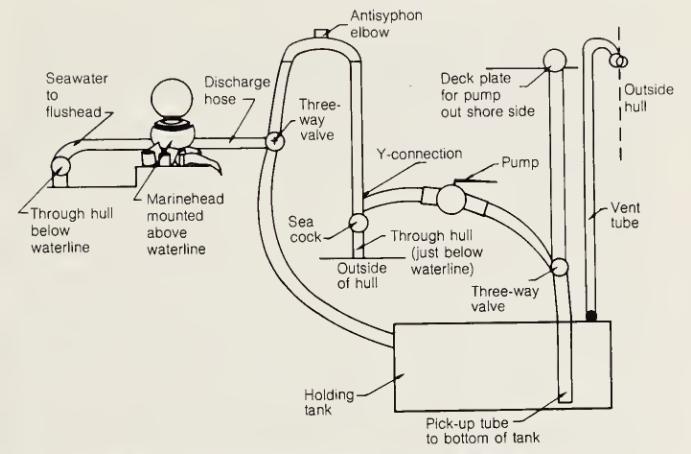

A standard marine head with a “Y” valve to either a holding tank or a through-hull for discharge offshore is a common installation. A deck pipe to the holding tank should also be included for pumping out at a shore station. Advantages include a larger capacity holding tank, a much less onerous emptying process, and the flexibility for direct discharge when offshore or in an allowed discharge area.

The disadvantages are that:

- it is a more costly and complicated system to install and maintain;

- extra space is taken up by the holding tank; there are holding-tank odors;

- and there is the risk of a leak or rupture in the holding tank or a line.

This is the preferred option for many owners of larger boats.

Another alternative is a standard marine head with a Coast Guard approved sewage treatment system, routed to a through-hull for discharge. Its advantage is the ability to discharge effluent in allowed areas without holding it for later pump-out or disposal at a discharge station.

Disadvantages include a complicated installation, large space requirements, odors, potential electrolysis problems, and the risk of a system failure. This system also involves higher cost, electrical demand, and maintenance. It is probably the least attractive alternative for most sailors, but in some jurisdictions it may be the only viable one.

All marine heads with overboard discharge systems should loop the discharge line high above the waterline through an antisiphon elbow. This is to prevent back-siphoning of water into the head, which can sink the boat. Heads, buckets, and Porta Potties should also be securely fastened down to avoid coming loose in a knockdown or at extreme angles of heel.

Whatever system you select, please respect the shellfish and your neighboring boats and don’t discharge in any marinas or small harbors with a slow water changeover.

Water Systems

A good rule of thumb for required water capacity for all purposes is one gallon per day per person. This assumes a conscientious effort to conserve. Water requirements can be reduced by using seawater for everything but drinking and the final rinse after a sponge bath or seawater shower and by supplying a large part of your liquid intake with canned drinks. If you keep track of water consumption for a few trips, you can develop a consumption figure that fits your sailing style.

The water supply should be divided into two or more tanks. An easy and inexpensive way to do this on a boat with one main tank is to carry enough jerry jugs of water to serve as both the extra and the emergency supply. Permanent tanks should be baffled with inspection ports for each section and should be securely fastened within the boat. The tanks should be vented inside the boat with 9/16-inch hose looped high under the deck. The freshwater deck fill plate should be sealed tight against saltwater intrusion.

Pressure water systems are convenient at the dock when water is in almost unlimited supply but can lead to use of an extravagant amount of water at sea. They make it particularly easy for guests to drain your tanks. If a pressure system is installed, there should be at least one manual freshwater pump in case the pressure system goes on the fritz. The best solution is to have a completely parallel manual system that can be used when you leave the dock.

Foot pumps greatly increase the convenience of a manual system, and if recessed, they can avoid being toe stubbers. Saltwater taps are another way to reduce reliance on fresh water, and if the tap is below the waterline, no pump is necessary.

Sinks should be deep and installed near the centerline. They should discharge slightly above the waterline. Showers should not drain directly into the bilge but should be routed to a sump and then pumped overboard. The head sink can drain into the same sump, thereby eliminating another through-hull fitting.

Stoves and Heaters

The type of fuel is the most important factor in selecting a stove or heater since it directly affects safety, cost, efficiency, and ease of use. After the fuel has been selected, the quality of the equipment and installation are important considerations.

Wood is cheap, readily available, and adds very little moisture to the interior of the cabin. Woodburning stoves are also inexpensive and require little maintenance other than cleaning. The disadvantages of using wood include the bulkiness of the fuel, the constant attention required to stoke the fire, the lack of control over the heat output, and the mess from ashes and soot both inside and outside the boat.

Read also: How to Choose the Perfect Sailboat: Tips on Selection, Ownership, and Alternatives

Coal, with many similarities to wood, can usually be used in the same stove. In contrast to wood, coal is less bulky for storage, has a higher heat output, and is messier before and after being burned. Since fewer homes and businesses now burn coal, it may also be hard to locate.

Alcohol is probably the most common fuel used on small boats in the United States. A large variety of stoves, ovens, and heaters are available. The advantages of alcohol include a clean flame when burning and a moderate flash point.

If on fire, alcohol can be controlled using water.

Its disadvantages are its high price, the difficulty in finding it in bulk outside the United States, a lingering sweet smell, and creation of a substantial amount of water vapor as it burns. In addition, alcohol has only about half the BTUs of other fuels. Consequently, it takes much longer for heating and cooking.

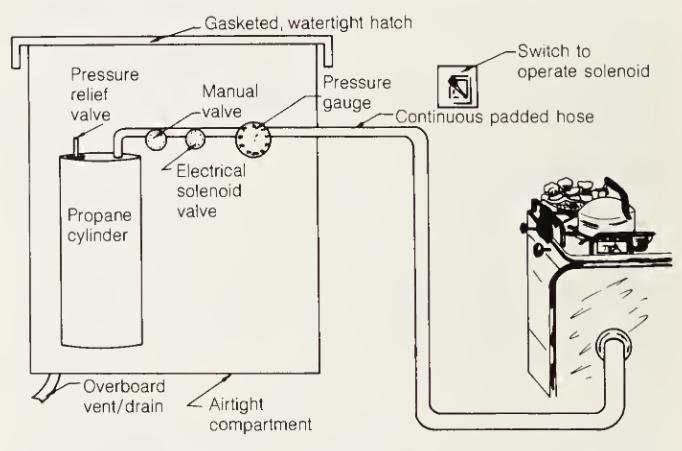

Propane and butane are now very popular on larger boats. Depending upon the amount of care you are willing to devote to the installation and maintenance of a propane or butane system and the degree of risk you are willing to accept, either may be a viable option. The advantages are a high heat output, ease of operation (no priming is required), infinite heat adjustment from simmer to high, and a clean flame.

It is also widely available, although a metric pigtail is needed outside the United States to fill the tanks. The complexity of the installation is a disadvantage. Also, the risk of an explosion from a fuel leak is high since both propane and butane are heavier than air and will settle in the bilge like gasoline fumes.

To maintain a safe installation, I strongly suggest the following for a propane or butane system. There should be no corrosion evident on any fitting or on the remote tank(s). The remote tank(s) must be stored in a watertight box or compartment that is vented overboard. It should be located as close as possible to the stove or heater. There should be a manual cutoff valve both at the tank and at the stove or heater.

Both valves should be easily accessible. In addition, there should be a second tank valve operable from the cabin via a solenoid with a warning light to indicate when the valve is open. The stove or heater should always be turned off at the tank first and the remaining gas in the line allowed to burn off. The tank should be fitted with a pressure gauge. The line from the tank to the stove or heater should be one continuous piece, supported at frequent intervals by padded brackets.

Compressed natural gas has similar characteristics to propane or butane, except that it is lighter than air and therefore creates less risk of an accidental explosion. It is bulkier than propane or butane and may be more difficult to find.

Diesel has always been very popular in the Pacific North-west and Alaska, particularly on fishing boats. The fuel is readily available worldwide, and if diesel-powered, the boat only requires one type of fuel. Diesel is relatively cheap and has a high BTU rating and high flash point (making it less likely to explode or catch on fire).

It can also be used with a wide range of burners. Unless it is burned correctly, however, diesel can be a dirty and sooty fuel. Diesel stoves also tend to be bulky and heavy, and cooking on them in the summer or in tropical climates can be insufferably hot.

Kerosene was traditionally the fuel of world cruisers, although pressurized gas is now more popular. Kerosene has a high BTU content and flash point and is generally available worldwide. The Primus/Optimus burners used in most of the kerosene stoves and heaters are generally interchangeable and are also available worldwide. The disadvantages of kerosene include a smoky flame if the burner isn’t clean or properly preheated and a difficult-to-adjust flame (hot or hotter). Also, each burner has to be primed before each lighting.

At colder latitudes, stoves with tops that resemble old-time cookstoves are useful. When the iron or steel top heats up during cooking, it can put out enough heat on a cool summer morning or evening to make lighting the fireplace or heater unnecessary. Since boat cooking is often very simple, an oven may not be necessary for your boat. A pressure cooker, stove-top oven, or Dutch oven will often save the space and expense of the full stove-oven combination.

When surveying the installation of any stove or oven, several criteria should be considered. The stove top should have sea rails and pot holders. If the stove or oven is gim-baled, it should be heavily counterweighted and have a lock to keep it from swinging.

Source: wikipedia.org

There should be a crash bar in front of the oven to keep the cook and crew from being thrown directly onto a hot surface. Areas behind the stove or oven should be accessible during cooking without risking a burn. Curtains should not hang over the stove or oven. The stove or oven should be securely fastened and bolted so that it will stay in place during a knockdown or rollover.

When selecting a heater for your boat, consider the latitude and season in which you will be sailing, your personal warmth level, and the total amount of time you are likely to use it. For occasional use, small fireplaces, wood stoves, or single burner pressurized heaters are probably the best choice.

For higher and longer heat requirements, diesel stoves or propane, kerosene, or diesel forced-air furnaces are probably a better choice. Live-aboards in northern climates and winter sailors should probably select two separate heaters, at least one of which is not dependent upon electricity (12 volts or 110 volts) to operate.

All heaters should be installed so that the crew can’t be thrown against them and burned. Convection heaters should be positioned as low and aft as possible for good heat distribution. Never use an unvented nonelectric heater in the boat without a number of hatches and ports open to vent the fumes.

- The fuel should always have a remote cutoff.

- The stove, oven, or heater should be insulated as much as is practical from adjacent flammable materials.

- Any insulation used should be covered by stainless steel.

- Stacks should be tall enough for a proper draft and should be capped with a Charley Noble (keeps the rain and spray out of the stack while letting the smoke out).

- The stack should not be near any flammable materials, and it should be insulated where it passes through the deck.

- Lastly, fully-charged fire extinguishers should be located close to each of these appliances.

Iceboxes and Refrigerators

An icebox is the simplest and cheapest approach to keeping food cold. It also has the advantage of being almost maintenance free. The obvious difficulty with ice is its limited longevity. Once the ice has melted at sea, you won’t be able to cool perishables or drinks until you can replenish your supply. This can be a constant hassle for the live-aboard, particularly in a hot climate.

When offshore, most sailors with iceboxes learn to adjust to the fact that the “cold” will only last one to two weeks. While coastal cruisers can usually find ice at marinas, lugging it to the boat may not be a favorite task. Iceboxes cannot maintain even temperatures as well as a refrigeration system, and they have no freezing capability.

The primary advantage of marine refrigerators and freezers is that they do not require ice to stay cold. They offer consistent “cold”, subject only to the reliability of the system and the availability of fuel. They are significantly more expensive to buy, install, and maintain than an icebox. When not plugged into shore power, the engine must be run a minimum amount each day to keep the refrigerator and/or freezer at the proper temperature.

The amount of engine time required will depend upon outside air temperatures, use and size of the refrigerator, amount of insulation, and efficiency of the compressor. A range of one to four hours per day is not atypical. “Cold” is acquired at the expense of fuel and your tolerance for Self-Survey Criteria for the Engine and Electrical Systemsengine noise, smell, and vibration.

An icebox for extended cruising should be able to hold seventy to one hundred pounds (approximately eight to twelve gallons) or more of ice and still have sufficient room for all the perishable stores. Our icebox, with only slightly above-average insulation, will hold 80 to 110 pounds of ice, plus perishable food. This typically lasts two weeks, generally permitting us to be independent of ice machines when coastal cruising.

Both iceboxes and refrigerators should have drains leading to sumps that can be pumped overboard. An even better solution for an icebox is a pickup tube to its bottom that is routed into the galley freshwater pump through a valve. The ice-melt water can then be used as a supplement to the freshwater supply (for other than drinking).

For maximum efficiency, an icebox, refrigerator, or freezer should open from the top and be insulated with four inches of foam, including the lid. Lids should be secured with hinges and hasps so they will not fly around. Be wary of iceboxes located where the top will receive direct sun, such as near a companionway. Small cockpit iceboxes are a nice convenience, but they must be sealed off from the rest of the boat or, like a good cockpit locker, be secured and have gaskets and deep scuppers.

Accommodations and Interiors

When evaluating the interior and the accommodation plan, you must consider the boat in two states: level with little or no motion, and under way with heeling and pitching motions. A sailboat that is used principally at the dock and in fair weather doesn’t need the interior of a blue-water sea boat. The most important criterion will be whether the boat is functional when not in motion. In contrast, the interior of a sailboat intended for offshore and heavy-weather sailing must meet much more stringent requirements.

A stylish interior that looks great when viewed at the dock or in the security of a cradle at a boat show may be dysfunctional, unlivable, or even dangerous in a heavy sea.

The following criteria will help you assess the practicality of a boat’s interior and how functional it will be at sea.

The companionway ladder should be easy to use and provide secure footing both going up and coming down, even if the boat is heeling or pitching. Handholds should be accessible along the entire length of the ladder. There also should be a way (for even weak individuals) to exit through a forward hatch in an emergency.

The cabin sole should have some type of nonskid surface, preferably one that is attractive and easy to clean. Teak and holly, used for the traditional sole, are nonskid, easy to clean, and very expensive. Teak-plywood veneers are common on newer boats. They are cheaper and fairly nonskid but don’t stand up well to wear and tear. Fiberglass soles with molded nonskid patterns are even less expensive but are usually unattractive and somewhat hard to clean.

Nonskid tape or matting, or a nonskid paint, may also be used. While effective, these are hard to keep clean and uncomfortable for bare feet. Rugs are the worst choice for a permanent cover, although builders often use them on new boats to cover an unfinished or unattractive sole.

Rugs slide around on the sole and get wet and moldy in the marine environment. If you want the advantages of a rug (warmth, foot comfort, and sound insulation) without the disadvantages, use one only at the dock or when anchored, and air it out frequently. When the rug is rolled up, it should reveal an attractive and functional nonskid sole.

There should be a wet locker for foul-weather gear. It should drain into the bilge and should be located as close as possible to the main companionway to avoid dripping water through the boat.

The boat’s interior should be organized so that crew members always have support against the boat’s motion as they move through the interior. Living-room-size expanses are dangerous at sea since supports are much farther apart. There should be plenty of easy-to-reach, through-bolted handholds in the passageways, galley and head, and above the settees. Grab poles at appropriate corners can do double duty as support for the cabin roof and as handholds.

There should be:

- plenty of storage space for food;

- extra water and fuel;

- clothes;

- tools;

- spare parts;

- fishing gear;

- sails;

- extra anchors;

- and other gear and equipment.

One rule of sailboat storage is that you never have enough. Many boats that appear spacious inside have created that openness at the expense of lockers, bins, shelves, drawers, and other forms of usable storage. A portion of the storage should be immediately accessible, with another part accessible without hours of searching and reorganization. Part of the storage space should be dry storage that will be reasonably watertight in severe conditions. Storage areas for heavy items should be available below the waterline.

Berths should be sufficiently high, long, and wide for comfortable sleeping without knocking your head, knees, or elbows when you move. Since few of us fit the dimensions of the “average” person, the best test of a berth is to get in it and try a few rollovers and a change of clothes drill. In particular, check the quarter berths, which should be the most comfortable berths on the boat but through poor design are often the worst. Three to four inches of open cell foam in the cushions is the accepted norm for comfort (this applies to all of the boat’s cushions).

If you can afford the price difference, closed cell foams are better because you can use a thinner foam. Also, they won’t absorb water like the open cell foams, and they provide additional pieces of flotation in an emergency. Leeboards or leecloths should be fitted to all berths that will be used at sea so that those sleeping on the windward side won’t fall to leeward and out of their berths. Many small boats convert the dinette into a double bunk.

This arrangement often works only in the builder’s brochure and should be checked for ease of setup, sturdiness, sleeping comfort, and impact on fore-and-aft passage through the boat. V-berths in the forecastle are another common way of adding additional berths. Unfortunately, the forecastle, a convenient spot to store sails, happens to be the most uncomfortable sleeping area in the boat when it is under way or in an exposed and rough anchorage.

The dinette table should be constructed heavily enough to support the weight of a crew member thrown against it. Take-down and folding tables should be checked carefully, since they are often flimsy.

The chart table should be located near the main companionway so the navigator can easily converse with the helmsperson. This also reduces the length of the trip (and the amount of water dripped) from the chart table to the cockpit position used for sights. The chart table should have a niche to store navigation instruments and tools. There should be extensive chart storage either in the table or nearby. A chart table that faces fore or aft provides a more consistent working angle on both tacks, and the navigator won’t have to fight to keep level with it. This type of table works best with a wraparound bucket seat with a safety belt.

To keep things where they belong as the boat heels and pitches, every countertop, table, shelf, and storage area should have fiddles (raised edges) at least one inch high. Cleaning is easier if the fiddles on the dinette table and galley counters have a few narrow breaks to facilitate wiping up spilled food. Storage areas should be divided with additional fiddles and vertical panels to keep the ship’s stores in place. This is especially useful if a storage area isn’t fully loaded. Drawers and doors should have a positive catch that will remain closed at extreme angles of heel. All corners should be well rounded to reduce the likelihood of injury.

There should be easy internal access for:

- inspection,

- rebedding,

- repair and replacement of all instruments,

- throughhull fittings,

- and deck-mounted equipment.

It is also helpful if a substantial portion of the hull is accessible for inspection and repair. All too often, good access is rare and minor repairs or replacement of equipment may mean dismantling or demolishing substantial pieces of the interior joiner work. Serious hull damage at sea may require taking an ax, saw, and crowbar to your interior to expose the damaged portion of the hull for temporary repairs.

A full inner hull liner is an easy way to stiffen the hull, provides some sound and heat insulation, keeps many of the leaks out of the main cabin, and provides a nice, clean interior. It also makes hull and coach-roof access very difficult and reduces the interior volume of the boat. Typical solutions to improving interior access include hinged doors, zippered or snap-out panels, and velcro closures behind instruments and major pieces of hardware.

At some point, every boat will develop deck leaks. But boats with better quality control will have fewer leaks since they use better sealants and take more care to bed down and seal every fitting and piece of equipment that goes through the cockpit, deck, or cabin roof. On a used boat, a conscientious owner will have fixed any leaks before they get out of control by pulling the offending fitting and rebedding it.

The most common leak areas are:

- the chain plates;

- stanchion bases;

- hatches;

- portholes;

- and windows.

The best test for leaks is to close up the boat and squirt water under pressure at every through-deck fitting, the edges of hatches, and other openings. Then check below for signs of unwanted water. On a used boat, you can also look for water and rust stains beside and under fittings.

The bilge should have a sump to catch and hold seepage from the propeller-shaft bearing, condensation, spills, and small leaks. Many modern boats have such a shallow bilge sump that at extreme or even moderate angles of heel, the bilge water is slopped into storage areas and over the cabin sole, creating a slippery and dirty mess.