Thinking “I want a boat”? Discover how to choose the perfect sailboat with tips on selection, ownership options, financial considerations, and alternative ways to access a sailboat, including crewing, sailing clubs, chartering, and more.

- Sailboat Selection Prerequisites

- General Considerations

- Financial Constraints

- How Will You Use the Boat?

- Personal Values

- Alternative Ways to Access a Sailboat

- Crewing on Other People’s Boats

- Sailing Clubs

- Chartering

- Shared Ownership

- Building Your Own Boat

- The Used Boat

- The New Boat

- Own Your Own and Charter It to Others

The single most important step in selecting a sailboat is to delineate clearly your personal and financial constraints, the type of sailing you hope to do immediately and in the future, and your initial expectations of a boat.

Sailboat Selection Prerequisites

If you take this first step seriously, you will dramatically increase the probability of a good match between your boat and you. Unfortunately, many potential owners fail to pursue this analysis except on a superficial level.

Consequently, they have unsatisfactory ownership experiences. The mismatches vary:

- a blue-water round-the-world cruiser being sailed or weekended on a lake;

- an underrigged heavy boat being sailed in a light wind area;

- a floating condominium being sailed offshore; a boat of questionable construction and design being sailed around the world.

Whatever the mismatch, the results are often unfortunate:

- termination of a live-aboard experiment because of cramped quarters;

- an aborted cruise because of an unseaworthy boat;

- too many days spent working on the boat and too few days sailing;

- more motoring than sailing on a poor performing boat;

- and at the extreme end, injuries and lost lives.

To increase your odds of avoiding these perils, think about your prerequisites. Be tough and honest with yourself. Ask yourself whether your assumptions are realistic, conservative, or optimistic. Put all of your requirements in writing and then Expert Tips for Negotiating a Boat Purchasediscuss and/or negotiate them with everyone who will be using the boat, involved in its maintenance and financial support, or seriously affected by your involvement.

The following represents a “starter” set of questions and issues from which you can develop your own list of prerequisites for selecting a sailboat.

General Considerations

What is your experience level in boating, sailing, and mechanical systems? What are your current and potential skills in both sailing and maintenance? What are your athletic inclinations? Would you enjoy hiking out over the waves all day? Who will go forward on a pitching foredeck in 20-knot winds to take down a No. 1 genoa that’s been kept up too long?

What are the trade-offs to owning a boat and sailing? Will you feel forced to use the boat because of your investment? Will you tire of eating macaroni and cheese to help pay for it? Will you miss those weekends in the mountains or on the tennis courts?

Financial Constraints

What is the maximum down payment or outright purchase cost you can afford? How much money is available from your take-home income for monthly payments? How stable is your income?

Did you remember to set aside money for equipping your boat? This can run from 20 to 50 percent of the “sail away” price on a new boat and may be comparable on a used boat that is poorly equipped or requires extensive modifications or repairs. Twenty to 30 percent for outfitting is a good rule of thumb. How desperately will you want that new spinnaker in a year or two? Have you budgeted for those items that seem optional now but may quickly become necessities?

Source: unsplash.com

What about insurance? A good marine policy can cost up to 1,5 percent of the insured value of your boat per year. What about maintenance, moorage, and unforeseen accidents such as that fouled anchor left behind in Port Blakely or that winch handle knocked overboard on your first sail?

How long before you resell the boat? Will this be a learner boat, your last boat, or a stepping-stone boat? The shorter your planned ownership, the more important local resale value and marketability will be.

How Will You Use the Boat?

Will the boat be raced, cruised, or chartered? Do you plan to sail in lakes and rivers, coastal or offshore? Are you a dockside, fair- or heavy-weather sailor?

How many days per year will you use the boat, and in which seasons? Will the boat be used primarily for day sailing or overnight cruises? How many nights per year do you expect to sleep on the boat, and in which seasons? What is the length of the maximum cruise you expect to take with this boat? How many people do you expect the boat to comfortably handle on a day sail and on overnight cruises?

How much motoring do you intend or will you have to do? Are you easily frustrated when the wind is light or the tide adverse? Do you typically have commitments on Monday mornings that can’t be missed because of fluky winds?

Personal Values

How important are the aesthetics of the boat to you? How important is quality of design and construction? Do you enjoy “roughing it” or do you prefer more of the creature comforts?

Do you like a responsive helm? How important is ability to point and boat speed? How many boats can pass you before you reach your frustration level?

Will you enjoy maintaining a boat? Will you maintain it at all? What will you enjoy more — working on the boat or sailing it?

Alternative Ways to Access a Sailboat

Your first decision, once you have decided to start sailing, is how to gain access to a boat. Obviously, most of the readers of this guide will have thought of buying. But is purchasing the right approach for you at this point in your sailing career? There are many sailors who don’t own boats and do a great deal of sailing. Perhaps they are novices who are unsure of their level of commitment or feel they are too green to own. They may be individuals who can’t commit money to a boat. Or they may be experienced sailors who have the means to own a boat but don’t want the responsibility of ownership just yet.

I consider my course in category How to Buy a Boat?“How to Buy the Best Sailboat” successful if several of the students decide NOT to buy. If this is your decision after reading this guide, it doesn’t mean that you won’t ever own a boat but only that the cold realities of ownership don’t fit your circumstances at this time.

The following represent the major ways to go sailing. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. Pick the one that best meets your current circumstances. After you have reviewed the entire guide, reread this chapter and decide whether your opinion of the best alternative has changed.

Crewing on Other People’s Boats

The easiest way to go sailing is with friends who already own boats. Make your sailing interests known to them, but don’t be subtle. Volunteer to help with boat maintenance, indicate your willingness to serve as a committed member of a racing crew, and accept all last-minute sailing invitations. All of these strategies will help get you on a boat. If you don’t have any receptive sailing acquaintances, hang out at the docks and inquire about boats that need crew.

Put up notices indicating your sailing interests at docks, marine stores, and sailing clubs. Or take out a “personals” ad in a sailing magazine. When you do get an invitation to sail, do your best to ensure that it will be repeated. This means adapting yourself to the boat’s routine and the skipper’s preferred methods, being alert to help the rest of the crew with their tasks, being honest with the skipper about your capabilities, and being sensitive to your “compatibility factor” with the skipper and the crew.

Crewing on someone else’s boat is a very inexpensive way to go sailing. With a talented and experienced skipper and crew, you may have a chance to learn a great deal of sailing technique and seamanship in a quasi-apprenticeship. If you are aggressive, you may also have the opportunity to sail on a variety of boats, perhaps in several different geographic areas.

The difficulty with this alternative is that you are completely dependent upon other skippers and their schedules, plans, and sailing habits. You may also become a specialist on the crew – e. g., in navigation, cooking, or foredeck work — and never have a chance to adequately learn and practice the myriad skills that go into sailing a boat. In some instances, your mentors (skipper or crew) may also be poor instructors or have incompatible personalities.

Sailing Clubs

Sailing clubs can be located by attending boat shows or checking the Yellow Pages. The advantages of clubs are several. They are relatively low cost, particularly when usage increases beyond the once-a-month sail. They usually offer more than one type and size of boat for sailing, though access to larger boats may be limited. Clubs often include sailing instruction and provide access to sailing partners and crew. Access to boats is usually quite good in the off season, when the wind is at its best, although this period also overlaps with the storm season. Finally, apart from the normal cleanup and unrigging of the boat, maintenance is usually taken care of by the club.

Source: unsplash.com

One major disadvantage of sailing clubs, at least in the long term, is that there is little incentive to learn how the boat’s equipment works or Prepare the Boat for the New Ownerhow to repair and maintain it. These are important skills for the boat owner and serious cruiser, who must be self-reliant. Further, a sailing club’s boats are usually very basically rigged and equipped for the average novice sailor. As your level of skill increases, this limitation becomes more and more bothersome. Because of the minimal outfitting and the beating the club boat takes from frequent use, even the best designs will usually perform below optimum levels. It may also be difficult to reserve a boat during the peak sailing season or on those exceptionally good days that occur in the off season.

Chartering

Chartering has a number of advantages. The cost of intermittent chartering is usually substantially less than owning a boat of comparable size.

Cost is not the only advantage. Apart from the usual cleanup and minor repairs while under way, outfitting and repairs are usually handled by the charter company. Chartering also provides an opportunity to sail many types and sizes of boats in a variety of cruising areas in this country and overseas.

This can provide the prospective boat owner with the chance to trial sail several or more boats under a wide range of conditions. It also permits sailors who love traveling but have a tight time budget to try out many cruising areas without taking a leave of absence or selling their houses. In terms of both dollar and time commitment, chartering allows more flexibility in pursuing alternate leisure activities, for example, skiing heavily one year instead of sailing.

Chartering does have some disadvantages, some of which echo the sailing club experience. There is little incentive to learn how the equipment works or how to repair or maintain it. Again, these soon become necessary skills for the serious sailor. Even if you have the desire, repairs may be difficult or even impossible because of unfamiliarity with the boat’s systems or lack of spare parts or tools. If the charter fleet has a “chase boat” and a good maintenance program, this will usually not be a problem. If the charter fleet doesn’t provide these services, you may be inconvenienced during your cruise, or worse, have your vacation seriously disrupted.

Another problem with chartering is that the chartered boat is either outfitted and equipped for a specific owner or has been designed and set up for the “average” client. This may be fine for a one-week cruise, but the charter boat will usually not fit your specific needs for long-distance sailing and extended trips.

Shared Ownership

With shared ownership, you split the cost and the maintenance responsibilities. This decreases the financial and time commitment required of the individual partners. In addition, shared ownership may provide you with constant fair-weather/foul-weather sailing companions. The disadvantages of jointly owning a boat can be significant.

Keep in mind that it is much easier to initiate than to change or dissolve a joint ownership arrangement. A good friendship isn’t enough. Even if you are sharing the boat with your mother, prepare a contract that spells out in detail how scheduling, costs, repairs, and improvements will be handled.

“Time-share” arrangements, a commercial version of the partnership, can be subject to a host of additional problems. Be certain to obtain satisfactory answers to the following critical questions before you buy a share.

Read also: Top 7 Secrets to Successfully Sell Your Used Boat

What is the stability of the managing organization? How long have they been in business? What prior experience do they have in this area? What is the current performance record of the managing organization on scheduling, maintenance, improvements, moorage, and so forth? Do you expect them to perform at this same level over the entire life of your time-share ownership? Are their profits made primarily on the initial sale of the boat to the time-share partnership? If so, what is their incentive to stay in business once they have sold a fleet of time-share boats?

What is the mandatory ownership period? Is it longer than the average life expectancy of the boat? Charter companies typically expect to turn over their boats every five to seven years or face making a substantial investment to restore them.

How much are the management and maintenance fees? Are there any variable use fees? Can the fees be raised? If they can’t, are the fees adequate to cover all costs associated with maintenance, since it is clearly in your interest to keep the boat well maintained.

What happens if the managing company doesn’t perform, or goes bankrupt? What are your rights, and what responsibilities might be shifted to you and the other owners? Can you liquidate your investment? What are your financial liabilities?

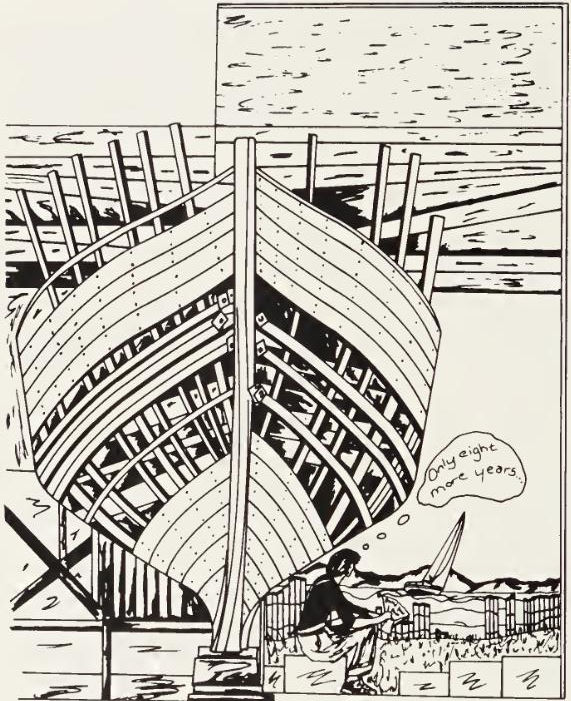

Building Your Own Boat

You may realize savings of from 20 to 30 percent if you build your own boat. You will also have the opportunity to personally control the quality of your boat at every stage of construction.

Boat building is an excellent hobby/avocation if you enjoy working with tools. It offers a chance to learn a wide variety of trades, such as welding and soldering, carpentry, cabinetmaking, fiberglass construction, painting, electrical work, plumbing, mechanics, and so forth. When the boat is finished, you will know exactly how all of its systems function and how to repair them. You will also have the personal satisfaction and pride of seeing your work progress to eventual completion.

Building your own boat does have a number of disadvantages. The labor involved is prodigious and may easily go into the thousands of hours – eight hundred to one thousand hours per ton is a good rule of thumb, and it is not uncommon for large boats to take five to fourteen years to complete. Some are never completed. Construction requires a large covered work space (not always popular with neighbors in a residential area), an assortment of good industrial grade tools (not inexpensive) and, in northern climates, heat.

You also have to become a general contractor dealing with hundreds of manufacturers, wholesalers, suppliers, and fabricators for work or equipment you’re unable to make yourself. You won’t have the advantage of a manufacturer who can make improvements with the second or third production units. Much of what you do will be trial and error. Reconstruction of both minor and major components will not be uncommon. In the worst case, you may discover major errors in construction, design, or performance after the boat has been completed. Obviously, you can’t test sail a boat you’re building to find out whether you’re really going to like all of its handling characteristics.

The cost savings from building your own boat may be elusive for several reasons:

- you have to call in experts for advice or assistance;

- you order materials you can’t use or return;

- you make mistakes and have to rebuild and reconstruct;

- you have to rent expensive space or buy tools (or make payments on a divorce settlement because you’ve become a recluse);

- and you may work on the boat during hours you could have been earning income.

The Used Boat

The price of a used boat (“previously owned”, in marketing language) may be substantially lower than a comparably equipped new boat because of depreciation, wear and tear, market conditions, or the seller’s financial situation. A used boat may include a great deal of extra equipment. It may be extensively customized, for example, with running rigging led to the cockpit, cabinetwork, and the like. It may have special character, be one of a kind, or be a unique model that has been discontinued.

The used boat has a history: prior owners are available for interviews, the ship’s log can be reviewed, and other boats of the same design may be available for comparison. If the boat has been seriously sailed, it should have been debugged and improved by the previous owners. Even if no serious flaws have been repaired, they should at least be apparent by now. If the boat has been well maintained, there should be less initial maintenance than there is with a new boat.

There are disadvantages to buying a used boat, of course. There is more “shopping” involved, such as phone calls, visiting marinas, and How to Choose a Boat Broker: Tips on Yacht Sales, Consignments, Fees, and Trade-Insmeeting with brokers and owners. This is because you have many more choices than with a new boat.

You are looking at a package sale that includes customization and extra equipment you may neither want nor need. With a new boat you need only select the basic design and then add or subtract features. More choices and previous customization may make it harder to find the boat that meets your specific needs or dreams. Usually this means that you will have to compromise to a greater degree. You may even be paying for equipment and customizing that either you don’t want or need, or that will interfere with future outfitting and modifications.

Even if the boat has been meticulously maintained, the normal wear and tear of sailing will shorten the life of the various systems. This means that major replacements and repairs, such as for sails, the engine, keel bolts, and so forth, will probably occur earlier. Parts for older boats and their equipment may be difficult to find. This can result in expensive custom fabrication of parts. Lastly, purchasing a used boat usually requires a survey.

The New Boat

Shopping for a new boat is somewhat simplified because you have fewer choices and you can look at groups of boats at dealers or boat shows. You have the potential benefit of the newest designs, materials, and technology. Of course, this is applicable only when the designer and builder incorporate new developments into their work on an ongoing basis. You can even visit the factory and see boats being constructed. Another advantage of buying a new boat is that financing is more readily available and is usually more generous. The new boat can also be equipped and customized to meet your specific needs. After the initial break-in period, maintenance should be less for the first several years.

The major disadvantage of a new boat is that it will cost more. In addition, you are responsible for the decisions, costs, and/or labor involved in outfitting a new boat. This process will be compressed into a relatively short time frame. Also, YOU will be debugging the boat. And every boat, no matter what its quality, will require debugging.

Own Your Own and Charter It to Others

The major advantage of buying and then chartering to others is that the costs of ownership are reduced through the charter fee and any available business tax deductions. In addition, many charter companies will handle all of the scheduling and maintenance of the boat in return for a percentage of the charter fee.

The disadvantages of chartering your own boat are several. To be successfully chartered, the boat shouldn’t be too uniquely equipped or customized. You may have to compromise your own desires in order to attract the average charter sailor. The best boat for chartering will probably resemble one of those designed for and used by the large chartering operations. The boat is usually chartered “in season”, when you will usually want to use it. Charter clients will cause both major and minor damage.

This may be hard to accept on a boat that is near and dear to you. The boat will receive additional wear and tear from increased usage. This means more maintenance for you during the off season and a shorter life span for the boat’s systems. In addition, to maximize tax write-offs, you must restrict owner utilization. Federal tax rules for 1984 require expense allocation between personal and charter uses, and if personal use exceeds the greater of fourteen days or 10 percent of the total days chartered, additional limits apply. Federal tax law — as well as state law if your state has an income tax — should be reviewed each year to determine current impact.