Buying a boat is a big deal. It’s important to inspect it thoroughly for any potential hidden defects that could lead to costly repairs down the road. Buyers should have a comprehensive inspection or hire a certified marine inspector to assess the boat’s structural integrity, engine condition, electrical systems, and hull. Issues like hull bulges, engine corrosion, or faulty wiring may not be immediately apparent, but can become serious problems over time. Moreover, checking the boat’s maintenance history can provide insight into past repairs and identify any recurring problems.

However, hidden defects may not always be obvious, even with an expert inspection. Sellers might unknowingly or knowingly withhold information about underlying problems. It’s important to include a contingency for such discoveries in the sales contract, such as a clause allowing for price renegotiation or the option to back out of the deal if defects are found after purchase. Buyers should also be aware of their local consumer protection laws, which can help safeguard against sellers who misrepresent the condition of the boat.

WHEN YOU ARE in the market for a new or replacement boat you will often go around a prospective purchase with the owner or broker in tow. Obviously he/she will be pointing out the good bits while you’ll be looking at it from the point of view of, «will it suit me? what needs doing?» Presumably you’ve done your homework before contacting the broker or private seller and have some idea of the type and make of boat you are after. This would suggest that the boat you are looking at now is close to your requirements and you want to assess its condition before buying it.

An advertisement may say that the boat is in «good condition» but exactly what does «good condition» mean? It may look smart and clean but most sellers tart up their boat before selling it. What you really want to know is: Are there any major problems with this particular boat that may only become apparent after you’ve purchased it?

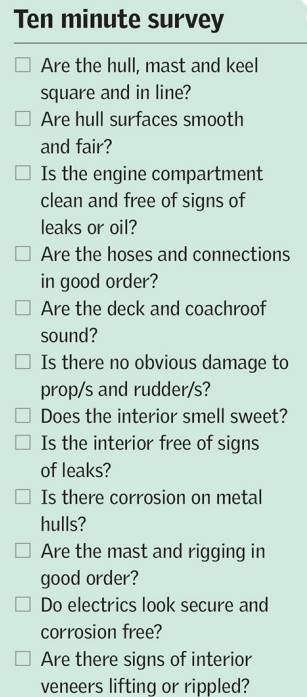

This is where the «ten minute survey» comes in: it gives you some idea of what to look for when you first tour the boat with the broker or seller. Obviously you will be paying attention to all of the good points the broker points out but at the same time you can be making an assessment of the general condition of the boat.

In ten minutes it is possible to get an idea of the Technical Advice on the Boat Inspection Process and Why Survey Your Own Boatcondition of a boat – not in detail of course, but it could be a sort of make or break point in the purchase process. In some ways this is a negative survey, not so much learning what on the boat is in good condition but whether it has suffered damage in the past or has been through a period of neglect. While the ten minute survey won’t give you any sort of guarantee that the boat is in sound condition, it could provide you with enough information to decide whether to look at the boat in more detail and then proceed to paying for a professional surveyor’s report, or walk away.

Before your visit

BEFORE YOU EVEN go to see the boat you’ll need to research the particular class you have in mind; the more you can find out about the boat before you visit it the better because you’ll have a strong foundation for your ten minute survey.

The survey

ALL SURVEYS SHOULD start in the same way, and that is to examine the boat from afar, then walk around it; you’re looking for anything that seems out of place on a well ordered boat. If it’s a sailboat check that the mast is in line with the hull and keel and that everything looks square and in order.

For both sail-and motorboats, check the sides, that the stanchions are upright and in line and everything is «square» and as it should be. Check the navigation lights and antenna.

OFF BOARD

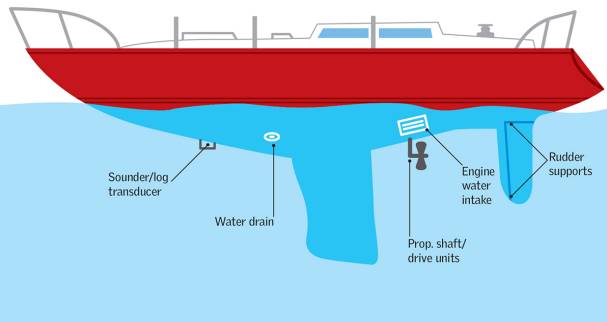

Now move closer for a more detailed look at the hull. If you’re Stern Gear – Technical Recommendations for Inspection and Maintenanceinspecting a motorboat it may be possible to get up close and personal with the topsides but the underwater parts may be concealed. With a sailboat it is often the reverse, with the topsides high above you but the keel area in clear view. In both cases, you can at least check the state of the hull finish – if it is dull, give it a rub to see if there is gloss underneath the surface grime. If not, you may find that a powder comes off on your hand when you rub the surface, which could mean that the gel coat is deteriorating and it may be time for a paint job.

If the hull is a composite look for any signs of the gel coat cracking, which could indicate a heavy coming alongside in the past or even a collision. With wooden boats be alert to signs that the seams between the planking are pushing out; while not a serious problem in itself, if it is accompanied by staining or rust streaks there could be something going on inside, such as corrosion of the fastenings. Look for signs of unevenness in the wood surface or cracks in the gloss finish, which may indicate wood rot beneath the paint. Ideally you’d want to test this with a pricker or tap with a hammer, but if neither is possible try tapping with a knuckle and if you hear a soft sound it could indicate soft wood. However, keep in mind that this is a quick test and not always fail-safe. If the hull is steel, be alert to the giveaway rust streaks of corrosion and if you come across them, take a closer look to see if there is any raising of the surface, which could indicate that the corrosion has set in to a greater depth. With an aluminium hull there shouldn’t be any signs of corrosion, but this softer metal can dent easily so look for fairness in the hull lines.

With any hull material you want to place your head as close to the surface as you can and look along the hull. Here you are checking that the hull remains fair and there are no giveaway signs of repair work, which may show as being slightly out of line with the rest of the hull. On a composite, look at the join between the hull and the deck mouldings to check for any signs of movement between the two or staining emanating from the join. On a sailboat check the join between the hull and the keel for any signs or corrosion or opening up, which should be viewed with suspicion: corrosion here could indicate that the keel bolts, if they are made of steel, are deteriorating, or it could just be corrosion on a cast iron keel. If the gap between the two has opened up slightly it’s time to drop the keel and take a closer look. On a motorboat you might have a steel keel band to examine and, again, you’re looking for corrosion between the hull and the band. Loose securing bolts may suggest a replacement band is in order; if the boat has a keel band it may indicate that the boat has been lying at a drying out mooring. Check along the edges of the spray rails and chines on a planing hull, since these are often gel coat-rich areas that are easily chipped.

At the stern try to move the rudder(s) to see if there is any play in the bearings and lift the propeller to check for the same in the shaft bearings. On both fittings you may be able to see whether the bearing holes are elongated through wear (if these parts are visible). Sailboat rudders take a lot of strain so look closely at the rudder surface for signs of cracks or deterioration.

ON BOARD

Now you have used up perhaps three or four minutes of your ten, so it’s time to move on board. Walk around the deck looking as closely as you can at the fittings and fixtures. This will particularly apply to sailboats where the fittings can come under a lot of stress, while on motorboats you’ll want to focus on the rails and the mooring fitting at bow and stern. Here you are looking for any spider-like dark cracks in the gel coat around the fittings and the mounting, which would indicate that they have been under stress at some point.

This is quite common with guard rails but if you see it around high stress fittings, such as chain plate anchorages, block tracks and winch or davit bases, it could indicate that there may be some form of trouble lurking within the mounting point of the fitting, which will need serious attention.

If the boat has a wooden deck look for any undue compression of the wood around fittings and any signs such as discolouration, which may indicate that there has been deterioration in that area. A fully laid wooden deck can be a sign of quality but be sure to check along the seams to ensure the sealing is intact.

Many boats today have a plastic imitation wooden deck which will generally remain intact, but look for any signs of lifting or poor bonding around the edges where water could get in below.

Try out the bounce test on the deck and coachroof so you can confirm their rigidity or otherwise. Any feeling of excessive movement may signal that the sandwich construction of the panels is breaking down, but it is difficult to specify what exactly is excessive movement: a normal deck should have very little to no movement.

Do the same test in the cockpit of both sail- and motorboats and if you find any movement, look for gel coat cracking in the corners or angles of the moulding.

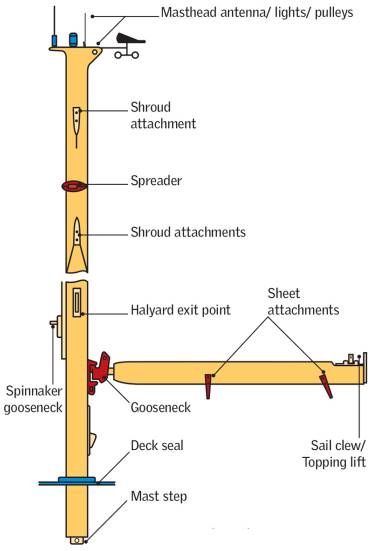

Next turn your attention to the mast and its fittings. Are there any signs of corrosion where the shroud or other fittings attach to the mast? As far as you can, inspect the attachment points of any high stress fittings and the attachment plate to ensure they are secure and intact. With the rigging screws, is there enough span left on the threads for further tightening and are both port and starboard screws adjusted to about the same position? If not, you may be faced with renewing the rigging or perhaps there is a problem with the mast step which has allowed the mast to drop down slightly.

These could all be warning signs of more serious trouble but it will be hard to be specific without much closer examination. Check the condition of the ropes that control the sails for signs of chafe or wear. Even replacing ropes can be an expensive proposition once you have 10 Steps Guide – How To Buy A Sailboatpurchased a boat.

The state of the engine compartment is perhaps your best guide for the standard of general maintenance around the boat. Here the need for maintenance and order is concentrated, and it should not take more than a quick look around to confirm the general state of the wiring, the cooling system and the engine and other machinery. Poor quality or badly maintained wiring will show in draped or loose wires (which may also indicate that there have been modifications to the wiring over the years) and corrosion around terminal areas.

All wiring should be tidily secured in place. If you can view the batteries, check they are firmly secured and clean and free of corrosion. Check the worm drive securing clips in the cooling system for corrosion; if it is present, it’s likely the hoses that the clips secure have not been renewed for some time. You should be able to see the seacocks at the water intakes in the hull bottom and if they too show signs of corrosion, it can signal that general maintenance has not been all it should have been. What is the condition of the exhaust pipe(s) and the engine itself? Is the engine clean and oil free and does it look as though it has had loving care and attention?

Use up any remaining time in your ten minute survey to inspect the boat’s interior. Look for signs of discolouration and/or staining around windows, hatches and the deck head covering, which could suggest leaks. It’s worth opening up a few of the lockers or floor hatches to get a view of the inside of the hull. On a sailboat, prioritise those in the bottom of the boat in order to get a look at what is happening to the keel.

Finally, if you can, try to inspect the steering system for signs of wear and tear or poor maintenance. If you can’t get to it easily at least turn the steering wheel or tiller to test if there is any play in the system; a small amount is okay but anything more than a quarter turn should be viewed with suspicion.

Now that you’ve spent ten minutes touring the boat, it’s time to come to a conclusion. What potential defects did you uncover and how does this affect the overall picture? There’s bound to be at least a few minor issues on a second hand boat, but if you come across a catalogue of potential faults you have two options: you can walk away and continue your search, or you can try to renegotiate the price, provided of course you have the means to resolve the issues once you’ve purchased the boat.

Read also: Equipment of a Sailboat: What You Need to Have on Board While Sailing

Since you’ve only had a ten-minute look round the boat, you won’t be in the strongest position to negotiate; a good broker or owner will already know about any defects you’ve picked up on and may well say that their price already reflects the condition. If this is the case, you could request a closer look at the areas that are worrying you, and this is where the content of this book really comes into play. If you’re still unsure, you could try to negotiate a price «subject to survey» and bring in the experts. At that point you’ll have a better idea of the condition of the boat and can still walk away should the professional opinion put you off the purchase.

Carrying out you own survey can be quite a lot of hard work and you need to be fairly fit and active. It can also be very rewarding and you will feel happier knowing your boat inside out, or if you are buying, you will have a good idea of just what you are going to get your hands on.

After the Survey

SO YOU HAVE spent the afternoon crawling around a boat and looking into all the parts that you do not normally see. Hopefully you have listed all defects and potential fixes, which will become a fantastic resource when you’re judging what steps to take next.

If you have surveyed a boat you’re thinking of purchasing you’ll probably want to adopt much of the negotiating strategy discussed at the end of chapter 13*. You might have quite a comprehensive list of potential defects and it makes sense to try and whittle this down to a more manageable length of the major items you feel detract from the value of the boat. You might include the following:

- The electrical system is showing signs of corrosion in some areas.

- There are gel coat cracks around many of the stanchion bases.

- Abrasion marks on the keel suggest the boat has run aground at some point since the last antifouling.

- There are signs of corrosion around the keel bolts inside the hull and along the keel/hull join.

- The rudder bearings show signs of wear.

- The engine cooling water system appears to be in poor condition.

- There are signs of leaking around the saloon windows.

You may even go back on board to show what you have found, although, short of dismantling the boat, neither you nor the vendor can be certain of just what is required to fix the problems. This is the time to confirm that you will bring in a professional surveyor for a second opinion, which will enable you to agree a «price subject to survey», based on what you have discovered during your inspection. If the vendor is being difficult, he will find it much harder to argue with a professional.

Of course, the alternative (and I strongly suggest you take it if a boat looks sad and uncared for) is to walk away from the deal. Call it a gut reaction, but first impressions are rarely ever wrong. After all, it is worth remembering that out at sea your life depends on the reliability of your craft.

You should also bear this in mind during a survey of your own boat. Some owners can become blinkered to severe problems; I saw one owner rebuilding the interior of an old boat and fixing it to a wooden hull riddled with dry rot, which he chose to ignore, thinking it would fix itself. The only real solution for that particular boat was to set fire to it in order to prevent the rot spreading to other boats in the yard.

If you’re finding it difficult to prioritise work that needs doing on your own boat, try separating the defects into several categories: those affecting the safety of the boat at sea, cosmetic problems, those affecting convenience or comfort on board and routine maintenance. By doing this, you can determine which items need to be completed by a boatyard and those you can handle yourself. The latter depends a great deal on time and your skill-set, but there is a lot to be said for doing the work yourself when you can, since you’ll learn a great deal about your boat.

There could also be items on your list that don’t have an obvious solution – they require further examination and possible stripping of parts to get a closer look. There may be possible corrosion on the keel bolts of a motorboat, or excessive play in the propeller shaft or the rudder bearings.

Whatever the issue, let a boatyard tackle the investigations, since they will view the situation objectively.

Surveying your own boat or a potential purchase is a bit like becoming a detective the day, but as long as you keep good records of everything you uncover, you’re more likely to be able to piece the clues together to arrive at a possible solution. You’re in a much better position to decide what the next step is, and if that means walking away from a boat, do it: next time you’re out at sea and something goes wrong, you won’t regret it.

Acknowledgements and thanks. My grateful thanks are due to Jessica Whitelock for the diagrams in the book and to the many people who helped with photos, in particular Tom’s Yard in Polruan, Berthon Boat Company and Lymington Yacht Haven. Also my thanks to the many owners who have asked me to do surveys on their boats over the years. There is nothing like hands-on experience.