Discover essential tips for properly and safely storing food on your boat. Learn how to use ice boxes, stoves, and other storage solutions to keep your provisions fresh and secure during your boating adventures. Perfect for ensuring a safe and enjoyable trip.

When you stop to think about it, the realization strikes you that most of the world’s great sea stories in one way or another have something to do with the subject of food. Great voyages, mutinies, shipwrecks… they all tell of how the fortunes and activities of seamen have been directly influenced by the availability or otherwise of food and drinking water.

Everyone has heard of sea biscuits, salted meat, rum and other staples in old-time seagoing diets. The nickname “Limeys” applied to Englishmen actually derives from their practice of issuing lime juice to seamen on old-time sailing ships, as a means of combating the dreaded vitamin-deficiency affliction called scurvy, which before the discovery of the value of limes often incapacitated whole crews on long voyages. Many a remote island or inlet was discovered, named, and sometimes even settled by roving seafarers for no more profound a reason than that one of them happened to put ashore there out of the urgent need to replenish vital supplies of food and water.

Even today, food is important aboard our pleasure craft. Just try taking a group of pals out for a day of fishing without a bit of food or drink aboard! It’s true that nobody will be in danger of expiring from lack of nourishment for one day … but the complaining his guests will do will most certainly give the thoughtless skipper a vivid idea of how an old-time sea captain actually felt deep down inside, when he first realized his crew was actively plotting mutiny!

Most fishing trips are one-day affairs. For this reason, presumably, the average fishing boat owner never does much thinking about marine ice boxes, refrigerators, stoves and seagoing menu planning. So when he does decide to spend a weekend or more aboard his craft, he’s apt to be all adrift in regard to what is what in this corner of the seamanship field. Lacking time to research the subject, he improvises. Every so often the results of doing so are deplorable and in later years the outing will be referred to among his friends as:

“The time we went fishing on Harry’s boat and discovered the hard way that the plastic container we thought held tea actually held pipe tobacco.”

There are many things to know about storing and preparing food aboard pleasure craft. In fact, several excellent cookbooks have been written on the subject, by people who have had a lot of experience in living aboard boats for extended periods. These books are written for yachtsmen and contain a surprising variety of recipes adapted to the peculiar cooking conditions that exist afloat.

Now you understand why recipes for stews abound in seagoing cookbooks; one pot can contain the meal’s meat, potatoes and assorted garden vegetables. This can be simmering on one burner while the other does odd jobs such as heating water for the coffee or making toast by placing buttered bread in a frying pan, or heating rolls in a double boiler. If the subject of culinary artistry afloat interests you, you can find such books in well-stocked marine supply stores located in areas where a lot of yachting is done.

Since these books are available, there’s no need here to go into much detail on the extensive subject of what foods to choose and how to prepare them aboard a boat. But we’ll skim over some highlights to give you a general insight on what it’s all about.

The average smaller, less pretentious pleasure boat’s food storage provisions usually amount to an ice box of somewhat limited size as measured by shoreside standards. One reason for the small size is that the designer doesn’t dare take too much of the available space for an ice box that may not be used all the time. Another reason is, the bigger the box the larger must be the cake of ice put into it, and you get to a point where a block of ice is too large to manhandle into a boat and then into its cabin.

Since the capacity of a typical boat’s ice box is limited in both food-holding and temperature-lowering capability, the member of your party in charge of food has to adjust his or her thinking rather drastically. When shopping for the home kitchen, rather slight heed is normally paid to how a particular food will be stored when it is brought home. There’s room enough in a typical commodious kitchen refrigerator for anything even moderately perishable to be popped into it, including apples, citrus fruit, English muffins, ketchup, tomatoes, some cheeses, carrots, Crisco, ground coffee and so on. Often the family owns a freezer, into which some things can be put to make more room in the refrigerator for the overflow of a shopping expedition.

But when shopping to stock up a boat’s galley for several days afloat, more planning and forethought is needed. There’s going to be room in the ice box only for things that really have to be kept chilled, such as milk and butter, eggs, meat, and vegetables such as lettuce, and celery. The more experienced the seagoing cook becomes, the cleverer he gets at planning menus that rely as much as possible on non-perishable items, thereby enabling the limited ice box space to hold as much as possible of things that must be kept cold.

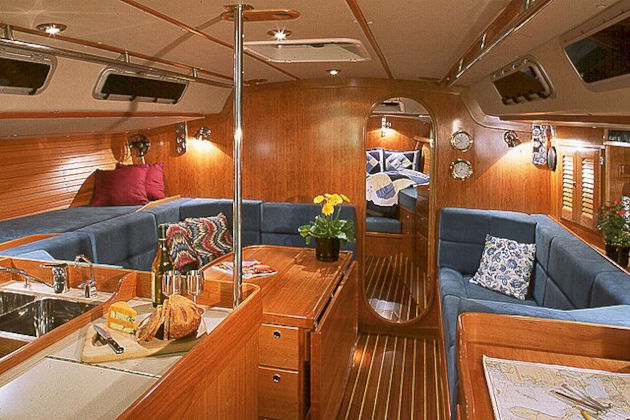

Fact of life No. 1 about a boat’s galley is that out on the bounding main, it can be difficult and even dangerous to stand up and walk around while cooking, as is done in a kitchen. It’s safer to remain seated, or at least standing in one place with hips braced against some nearby cabin member. From this it follows that a boat’s galley has to be small so that ice box, sink, stove and work table are all within arm’s reach.

Source: wikipedia.org

Trouble comes when a landlubber tries to make such a galley produce the kind of dishes familiar back home. Happiness comes when the struggling cook realizes the trick is to tailor the menu to the galley.

Fact of life No. 2 about food preparation aboard is that real marine ice boxes open from the top, not from the side. This causes many a spouse to howl about the crazy, awkward, top-opening ice box in the new boat. She has to lift some things out to get at what’s under them, and can’t use the top of the closed ice box as a table. But it’s crazy like a fox!

Read also: How to Buy the Best Boat? Essential Tips

Because, if you have a side-opening ice box and open it while out on the sea, or even in a mooring area when the wake of a passing boat happens to come rolling along, the block of ice and most of the foodstuffs are quite likely to jump right out at ya!

Fact of life No. 3 is that every time the door of a side-opening ice box is opened, all the cold air in it slides down and out and the warm air which flows in to replace it then has to be cooled off by the ice – a process which accelerates the shrinking of the ice block.

It’s useful to have an elementary grasp of the physics of an ice box. All the chill in it comes from the block of ice, whose size is limited. When ice is put into a box that has been standing at room temperature, its first job is to chill the inner surfaces of the box. Then if food at room temperature is put into it, more cold must be extracted from the block of ice to chill it, too. Knowing this, the foxy thing to do is to put an oversize block of ice in the box the day before embarking on a cruise. Bring well-chilled food from home in a picnic ice box that, after being emptied, can be used to hold your supply of cold beverages. If you can bring frozen foods, so much the better – they will have to be used when they thaw but when they’re first put into the ice box their coldness will make life easier for your main ice block. Arriving at the boat, the big block can be cut down as necessary to make room for the food. With both the inside of the ice box and the food going into it pre-chilled, what remains of the ice block has less work to do and will last longer at sea.

Ice inside the block does not melt at the same time that ice on the surface is melting. It’s melting of the surface ice that does the work of chilling – cold that kept the water frozen is given up to the air, chilling it. A block of ice one foot square contains eight times the volume of a block of ice six inches square, instead of twice as much as you might say if you spoke up before thinking it through. Thus, a block of ice twice as big as another one does not take twice as long to melt, it takes somewhat longer. If a block of ice is chopped into several pieces, you still have the same number of pounds of ice, but much more surface area is exposed to the air to speed melting. It will melt faster. This means that to make ice last as long as possible at sea, put the largest possible single block of ice into the ice box that you can manage and still pack the food in.

You can juggle your ice supply this way or that to get the results you want. Crushed ice chills things fastest because it melts fastest. Ice cubes won’t last as long as a block of ice of the same total weight. Champagne is put into buckets of chopped ice to chill it quickly; a block of ice won’t chill food so quickly, but you can pre-chill your food and then rely on the ice block to keep it cool for a considerable period of time. It’s smart ice management to keep food in one ice box and cold drinks in another one. People will be fishing beers and cokes out all day long, the cover will be opened constantly, and the repeated loss of cold air in the box will extract its toll from the ice in the drink box. Let only the cook open the box containing food, and instruct him to open it as little as possible while preparing meals. That way, you might end your weekend afloat sipping warm canned beverages, but at least the food will still be in safe and edible condition.

For this reason, along with the attractive market afforded by the modern huge recreational boating movement, more and more firms have been developing and introducing compact marine refrigerators. These are available to operate on various voltages ranging from 12 to 110, so they can be used in most boats having electrical systems. A variety of designs is available to suit everything from smaller cruising and sportfishing boats up to palatial yachts. The advent of frozen foods has been as much of a blessing to cruising people as it has been to landlubbers, for now it is possible to carry perishable foods on long trips without spoilage problems. So even freezers are now available. Some are styled to fit well into boat galleys, and there are even units that resemble the fish boxes carried in the cockpits of sportsfishermen but which are actually combined freezers and refrigerators. They’ll keep frozen bait and food in good condition, store fish and food too. Prices for things in this field vary … you can get simpler units at prices in line with what you’d expect to pay for chain saws or smaller outboard motors.

The marine stove of necessity is a specialized critter. It has to be safe and function satisfactorily while the boat tosses and rolls under it. The enclosed spaces with poor ventilation created by a boat’s cabin, bilge area and hull creat safety problems not encountered in the home.

For a long time, pleasure craft used small coal stoves. They are still being made and come in various sizes and styles, some very cute indeed. The big advantage of coal as a fuel is that it is safe aboard a boat. It won’t leak, it won’t soak things, it does not give off explosive vapor, it won’t burst into angry flame suddenly. A small coal stove can make sense even today aboard boats used a lot in damp and chilly weather, such as in the northern states and from early spring to late fall, as it will serve both for cooking and cabin heating. But it’s not so good for cooking alone; it takes time to bring it up to heat, requires constant adjustment, and is messy.

The alcohol stove is the most commonly used type in smaller cabin pleasure craft. Its prime advantage is that within the field of liquid fuels, alcohol is the safest shipmate. Its vapors do not concentrate in explosive ratios in the air of a boat’s bilge. If spilled, because it mixes with water, any available water can be used to dilute it and wash it away. Kerosene stoves were once common, but good, clear stove kerosene is now as hard to get as buggy whips at an automobile show and, even if available, has a tendency to seep into everything and make food taste bad. Gasoline as a stove fuel aboard boats is terribly dangerous and its use is outlawed.

Not knowing that alcohol stoves are used because their fuel is safe aboard a boat, many newcomers to boating detest their alcohol stoves. They don’t read instructions, don’t understand how the fuel behaves in the burner mechanisms, use any commercial alcohol they happen to pick up rather than refined stove alcohol, and then fuss and complain when the stoves misbehave. It’s too bad that safe boating courses don’t include lectures on “The Care and Feeding of Your Alcohol Stove!” Cared for and used properly, an alcohol stove made by a recognized and reputable marine supply firm can do a good job.

As boat size grows, there’s more room for niceties. Bottled gas is a favorite fuel for stoves in larger pleasure craft. It’s clean and odorless, gives a hot flame, and is quick and easy to turn on. Tanks must be located outside the boat, usually under some sort of well-ventilated cover, and piping must be done carefully to avoid danger of leaks. Properly installed, an approved-type marine bottle gas stove is safe and its fuel is today readily obtainable in almost any port. Wrongly installed or poorly cared for, of course, bottled gas is as dangerous as gasoline. Never use gas stoves or other appliances designed for use ashore, use only makes or models designed for marine use and bearing a label attesting to that fact.

Having had trouble with their alcohol stoves, some newcomers have in recent years taken to using camping-type propane stoves fed by small disposable metal containers. They get away with it because these stoves are usually new and in good condition. But there’s always the chance of a loose connection or a worn fitting allowing gas to escape. Thus far, marine safety officials have not issued any warnings, pronouncements or rulings about the use of such stoves in boats. There’ll probably have to be an accident or two before they wake up to what’s going on. Some boaters have even been using camper-type catalytic heaters in the cabins of their boats. One of the dangers of any kind of stove in a boat, be it coal, alcohol or gas, is that is consumes oxygen in the cabin’s air. If chilly boatmen have the cabin closed up tight to try to get warmed up, they can wake up some morning to find themselves suffocated! Always, always remember to provide good ventilation, both to let fresh air in and combustion products out.

Cooking can be done safely on Sterno stoves; the fuel is safe and trouble-free. The ordinary collapsible sheet metal Sterno stove is not suitable for marine use, as it isn’t fastened down and has no guard rails. On the market are gimbal-supported stoves for Sterno that take little room and are good for occasional quick heating jobs such as making coffee or heating canned soup. There are even barbecue-type stoves that burn charcoal or briquettes and are fitted with brackets that hold them outside the boat’s gunwale so sparks and hot grease will drop harmlessly into the water. Presumably a hibachi could be used for cooking if it was located in a safe place well away from whatever inflammables the boat may contain. A good marine stove is made so it can be fastened down to the galley counter, and is fitted with side rails that will keep hot utensils from sliding off into the cook’s lap when waves make the boat rock. Seagoing stoves have clamp bars that attach to these rails and hold utensils firmly in one place on the stove tops.

At the top of the luxury scale are electric and electronic stoves, usually seen aboard luxury cruisers. As houseboats have become more and more common on inland waters, stove and refrigerator units origin¬ ally designed for use in mobile homes have been adapted to use aboard them. A fairly recent trend in smaller powerboats is to build the stove, sink and water tank into one compact galley unit, installed in the boat as a unit. In the old days it was assumed boatmen would seek shelter from bad weather in the cabins of the boats, so galleys were located in the cabins. The big and spacious cockpits of modern powerboats has en¬ couraged boatbuilders to move the cooking provisions out into the cockpit. It’s now assumed that a lot of cooking will be done in fine weather, so moving the galley into the cockpit makes sense. There’s more head- room and the cook can usually walk about; ventilation is automatic, a malfunctioning stove or burning frying pan can if necessary be heaved directly overboard to stop it from setting the whole boat afire; cabin space is released for sleeping and lounging use, and when the owner isn’t going to do any eating aboard the galley unit can be left ashore, freeing cockpit space for fishing activities.