How to buy first boat and make the right choice requires careful preparation and consideration of various factors.

The first step is to determine your budget. Besides the cost of the boat itself, it’s important to consider additional expenses such as insurance, maintenance, docking fees, fuel, and necessary equipment. This will help you avoid unexpected financial difficulties.

Next, you need to decide what type of boat you need. This depends on how you plan to use it. For example, a fishing boat is different from a sailing boat, and a boat for leisurely lake trips is different from one designed for ocean adventures. Consider the size, features, and capabilities that match your intended use.

Research is crucial. Look into different models and brands, read reviews, and talk to experienced boat owners. Visiting boat shows and dealerships can provide hands-on experience and help you get a feel for what’s available.

Once you have a good understanding of what you want, it’s time to inspect potential boats. Whether you’re buying new or used, a thorough inspection is essential. For used boats, hiring a marine surveyor can be a wise investment to identify any hidden issues.

After finding the right boat, take it for a test drive. This will help you ensure it handles well and meets your expectations on the water.

Finally, complete the purchase by handling all the necessary paperwork, including registration and title transfer. Don’t forget to arrange for insurance and secure a safe docking or storage space.

By carefully considering these steps, you can make a well-informed decision and enjoy your new boat with confidence.

Buying a New Boat Step by Step

In the point «Step-by-Step Guide to Choose the Boat for YouCase History» you read about how the Smiths bought a boat. It has always seemed to me that they went about finding a boat in a good way. They had a size and price range in mind when they started. Of course, it turned out that they wanted more in a boat than the initial size would allow, but they did start with something definite in mind to give their search direction.

So, take some sort of starting point yourself, either size or cost, and start visiting the places where boats are on display. In the New York area, all the boat dealers advertise in the sports section of the Sunday New York Times. Initially, it might be best to look for a dealer who seems to have more than one boat to look at on a given boat-hunting day, since you should try to see as much as you reasonably can to give yourself as wide a range of choices as possible. Browse around and, at first, don’t get too deeply involved in the process outlined in this article.

Like a person, a boat is an amalgam ofmany different characteristics. Find several boats that appeal to you for whatever reason and then run through the evaluation process given in the point «Manufacturing of Fiberglass Boats and Design FeaturesClues». You will probably then be able to narrow the choice down to two or three boats. At this juncture you will have a general idea of the price of the boats. The thing to do next is to sit down and price the boats with the same equipment (suggestions on this are given in the point «Step-by-Step Guide to Choose the Boat for YouChecklist for New Boats»).

Let’s say you have finally come down to a choice between two boats A and B. Here is how a detailed comparison between them might look:

| Boat A | Boat B | |

| Length overall | 32′ | 33′ 5″ |

| Load waterline length | 25′ | 27′ |

| Draft | 5′ 6″ | 5′ 6″ |

| Beam | 10′ 3″ | 10′ 6″ |

| Displacement | 9 500 pounds | 11 500 pounds |

| Sail area | 465 square feet | 505 square feet |

| Retail base price | $60 000,00 | $54 000,00 |

| 4-inch-thick mattress | Standard | 163,00 |

| Jib halyard winch | Standard | 130,00 |

| Boom vang | 250,00 | 260,00 |

| Ladder | 350,00 | Standard |

| Gate | 190,00 | Standard |

| Extra battery | 125,00 | 125,00 |

| Lower lifelines | 275,00 | 305,00 |

| Sheet winches | Standard | 84,00 |

| Genoa gear | Standard | 88,00 |

| Vent hatch | 225,00 | 205,00 |

| Boottop and bottom paint | 375,00 | 411,00 |

| Cradle | 425,00 | 455,00 |

| Freight, commissioning | 1 925,00 | 1 535,00 |

| Total | $64 140,00 | $57 761,00 |

| Three sails, sail cover | 3 865,00 | 3 995,00 |

| Total | $68 005,00 | $61 756,00 |

| Knotmeter, depth finder, VHF, Loran | 4 650,00 | 4 650,00 |

| Total | $72 655,00 | $66 406,00 |

| Cost per pound | $7,64 | $5,77 |

Now, at this point you have satisfied yourself that the two boats are pretty nearly equal, as far as fundamental structure goes. Thus, on the face of it, you might immediately pick Boat B because it will offer you close to a $6 000 savings. You figure this $6 000 will cover the cost of the additional items you are going to need or want – such things as anchors, fire extinguishers, life preservers, and a sailing dinghy.

You know, however, that Boat B has an iron keel, whereas A has a lead keel. At the current prices of lead, the keel in A is worth about $3 000 more than the cast iron in B. So, the difference in the price has shrunk to about half. Not much when you are going to be investing $72 000. In addition, Boat A has natural teaksurfaced bulkheads, while B uses a teak-grained Formica, which is cheaper and, while quite nice, not as nice as the real thing. Figuring that the teak is probably worth $2 000 more than the Formica, the price differential is insignificant. How are you going to choose? Well, consider these factors.

Boat B is 2 feet longer at the waterline than A. As you will see in the article «Instant Naval Architecture», this means that B has a higher speed potential. In 8 to 12 knots of breeze, B should travel at about 5,6 knots and A at about 5,4. This may not sound too significant, but in ten hours of sailing it would put B about a half-hour ahead of A. The difference would be slightly greater as the wind blew harder and less as the wind decreased.

The assumption is being made here that these two are similar types and, in my example, they are. Both are modern, light-displacement boats with fin keels and freestanding spade rudders. Also, B is a full ton heavier than A and, so, would have an easier motion in a seaway and be more comfortable to be on.

It will be interesting: Self-Survey Criteria for the Basic Boat

An interesting test can be made at this point by dividing the weight of each boat into its total cost. For Boat A, this gives a cost per pound of $7,64 and, for Boat B, $5,77. Boat A is, therefore, 32 percent more expensive per pound than B. Now what do you do?

Well, if you’ve already decided that the boats are equal structurally and if what you want is the most boat for the money, B is your choice. You could equally well decide, though, that you like the better interior finish and generally better detailing on A and figure you would rather have the smaller, «nicer» boat. The point is that you can now make a rational choice based on concrete aspects of the two boats, aspects which you have evaluated using your own eyes, hands, and judgment.

My personal choice, by the way, would have been the larger, heavier Boat B, but I would surely understand anyone who decided on A. The point is that you need to analyze a boat down to the point that you can decide what it is, specifically, you are buying. In this case, it came down to a choice between interiors in what were, basically, equally well-made boats.

The trade-off was between a larger, plainer boat and a smaller, more nicely appointed boat. The cost-per-pound analysis helped to reveal this basic fact. As the man says, there is no free lunch – you get what you pay for, and the techniques of point «Clues», plus the cost-per-pound analysis, help reveal what it is you are paying for. If the choice was A, you were paying for the interior; if B, the greater size of the boat.

So far we have been talking mainly about new boats in and of themselves, but boats are not built in a vacuum, nor are they sold in one. In order to look at boats, you have to go to a place where they are on display – the boat dealer’s place of business, which is normally at a boatyard.

Many people do not realize this, but the boats that are on display are not there on consignment from the builder. They belong to the dealer and have been paid for by him, either directly out of pocket or by what is called «floor planning». This is an arrangement with a bank or other financial institution in which the dealer puts up 10 percent or so of the required cash, the bank puts up the rest, and the dealer pays interest and repays the bank as the boats are sold. Fair amounts of money are involved in this. A dealer with three major lines may need to stock twenty-four separate boats in order to display one of each model manufactured by the three separate companies. This can easily run to a million dollars sitting on the showroom floor.

I am making a point of this because it is another factor you may want to consider. You are going to be expected to leave a substantial sum of money with the dealer when you order your boat, and you may feel more confident when you do this if you can see some evidence of financial solidity on his part. Another obvious test of this nature is to find out how long the particular dealer has been in business at that spot.

Now, while you have been looking and browsing, you will have been talking to a salesperson in the boat business who is generally called a broker. Brokers are commissioned salespeople. In other words, he or she is paid when the sale is closed. You will find, I think, that a How to Choose a Boat Broker: Tips on Yacht Sales, Consignments, Fees, and Trade-Insknowledgeable broker can be a big help to you in the buying process because he can answer many questions and often suggest alternatives that you might not have considered. Basically, a good broker will try to find (from among the boats he sells) the boat he feels best fits your tastes and needs and then show you why.

Once you have found the boat you want, you will have the choice of either buying the boat on display, if it is unsold, or ordering a boat like it to be made for you. In either case, once you have reached this point, there are certain specific things that have to be done.

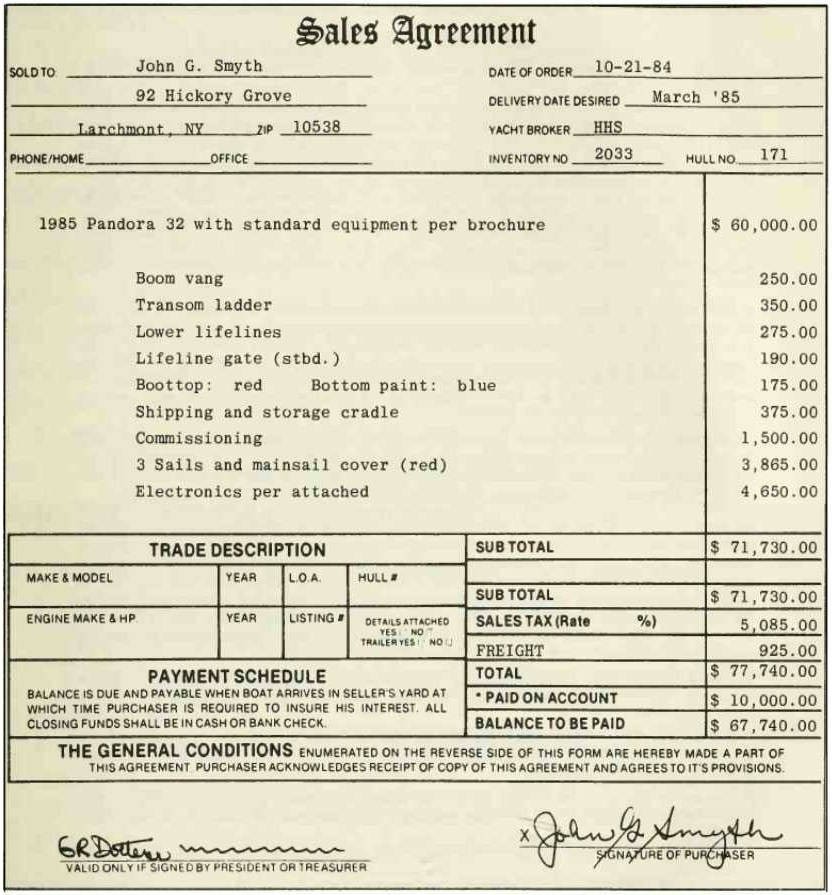

First, you will sit down with the broker and decide on the specifics of your boat – color, equipment, size of winches, and other details. These things will be written out on a sales agreement or contract to be signed by you and an officer of the company.

At this point, a check for 10 to 15 percent of the purchase is normally required from you. After you have written it, you have completed the process of ordering a new boat.

Now there will be a lapse of time of weeks or months until the boat is completed by the factory. When your boat is completed, it is normally shipped by truck to the dealer, who then will launch, rig, and commission it. Once again, your boat is not shipped to the dealer on consignment. The dealer must pay for it before it is unloaded from the truck. Therefore, you will be expected to pay the dealer very soon after the arrival of the boat and this is usually stipulated quite plainly in the sales agreement.

At this point, it might be a good idea to look at a typical sales agreement. The front is filled out to reflect your purchase of Boat A; the back, reproduced below, is fairly standard in its conditions.

- This Sales Agreement shall be valid only as and when accepted in writing by the Seller signed by either its President or Treasurer.

- In the event the manufacturer of any item covered by this Sales Agreement shall increase or decrease the selling price thereof to the Seller prior to delivery to the Seller, the price of any item enumerated herein shall be increased or decreased by an amount equal to the percentage of increase or decrease on such item which the Seller shall be obligated to pay to such manufacturer. In the event, however, that the purchaser may be dissatisfied with such price change, he may, within ten days notice of such price change, cancel this order; in which event if a used boat and/or engine has been traded in as part of the consideration herein, such used boat and/or engine shall be returned to the purchaser upon the payment of a reasonable charge for storage and repairs (if any) or, if the used boat and/or engine has been previously sold by the dealer, the amount received therefor, less a selling commission of 10 % and any expense incurred in storing, insuring, conditioning, or advertising said boat and/or engine for sale, shall be returned to the purchaser

- Upon the failure or refusal of the purchaser to complete said purchase within 10 days after delivery by builder and notification to the purchaser, for any reason other than cancellation on account of increase in price, the cash deposit may be retained as liquidated damages; and in the event a used boat and/or engine has been taken in trade, the purchaser hereby authorizes the Seller to sell said used boat and/or engine; and the dealer shall be entitled to reimburse himself out of the proceeds of such sale, for the expenses specified in paragraph 2 above and also for his expenses and losses incurred or suffered as the result of purchaser’s failure to complete said purchase.

- The manufacturer has the right to make any changes in the model or design of any accessories and part of any new boat and/or engine at any time without creating obligation on the part of either the Seller or the Manufacturer to make corresponding changes in the boat and/or engine covered by this Sales Agreement either before or subsequent to the delivery of such boat and/or engine to the purchaser.

- The Seller shall not be liable for any delay or default due to: Acts of God, delays in transportation, inability or delay of manufacturer, supplier or seller to obtain necessary labor, material or equipment to complete delivery of boat in proper working condition; strikes, fires, floods, accidents or other causes beyond the control of the Seller.

- The price of the boat and/or engine quoted herein does not include any tax or taxes imposed by any governmental authority prior to or at the time of delivery of such boat and/or engine unless expressly so stated, but the purchaser assumes and agrees to pay, unless prohibited by law any taxes, except income taxes, imposed on or incidental to the transaction herein, regardless of the person having the primary tax liability.

- The Seller has made no representations nor makes any representations, express or implied, regarding the equipment covered by this order, except that the Seller will deliver to the Purchaser good title to said equipment free from all liens and encumbrances. Warranties by Manufacturers of the equipment covered by this order are limited to such written warranties as may accompany the individual items of equipment ordered hereunder. In all events, the Seller’s warranty is limited to an obligation, subject to performance by the manufacturer of such equipment, to repair or replace any item of equipment sold hereunder, at Seller’s own expense, which proves to be defective in workmanship or material, only to the limits set by the written Manufacturer’s warranty. No officer or other representative or agent of the Seller is authorized to assume any other liability or obligation in connection with the sale of the equipment or materials covered by this order, and no other liability or obligation may be assumed.

- In case the boat and/or engine covered by this Sales Agreement is a used boat and/or engine, no warranty or representation is made regarding said used boat and/or engine, it being sold «as is» in its present condition.

- Title to the goods or boat(s) covered by this Sales Agreement shall remain in the Seller until all sums due and to become due hereunder shall be fully paid in cash by the Purchaser and until Purchaser accepts delivery of the boat at the place he designates for delivery.

- This agreement may not be changed orally in any respect and contains the full and complete understanding between the Seller and the Purchaser regarding the purchase, sale and delivery of the equipment enumerated herein.

The agreement should specify a month of completion, since a good builder will normally meet these dates within five to ten days. Nevertheless, early ordering is a good idea and, in our area (northeastern US), most auxiliaries wanted for spring delivery are ordered by Thanksgiving. Remember that even the largest builders can build no more than about six hundred boats a year.

You may have noticed the area at the bottom of the contract where it says «trade description». Many people are not aware that they can use their present boat as part payment for their new boat. In fact, some dealers will not take trades because of the financial risks involved.

You see, if a dealer takes your boat in trade and has not sold it by the time your new boat arrives, he has to come up with whatever amount of cash he has allowed you in order to pay the manufacturer for the How to Choose Your First Boat?new boat. Some dealers do take trades; the advantages to you are often considerable.

The biggest advantage is the fact that sales tax is figured on the difference between the price of the new boat and the amount allowed for the trade. Thus, if you were buying a $60 000 new boat and your trade was valued at $20 000, instead of paying, say, 5 percent of $60 000, or $3 000, in sales tax, you would pay $2 000, thus saving $1 000.

In addition, if you don’t have the time or inclination to find a buyer for your boat, you aren’t going to have to pay a broker to find one for you. The company that takes your boat in trade will have to do that. In those parts of the country where boating is seasonal, if you trade your boat at the end of the season you will be spared the costs of winterizing and storing the boat until the next season.

Generally speaking, the reasons for the purchase of a new, rather than a used, boat can be summed up as follows:

- The boat may be a new model not previously available.

- You can have the boat the way you want it in terms of equipment, colors, and so forth.

- Everything is brand-new and at its greatest strength and longest useful life.

- The problem of what to do with your present boat can be solved.

- You get a warranty.

- Because there is a warranty, certain problems can be expected to be taken care of by the builder.

In connection with this last point, what follows is the wording of a fairly typical warranty certificate issued by (in my opinion) one of the better manufacturers of stock, fiberglass auxiliary sailboats.

The most important thing to know about a warranty is who is going to carry out the work if any is needed under the terms of the warranty. It is important for you to find out if the dealer you are buying from has a boatyard which is directly under his control or if he simply «farms out» any service work.

Obviously, if he has his own yard, you, as a customer, have much more clout. This also holds true for the commissioning (making ready) of your boat when it arrives from the factory. Ask the broker about these things and, when you leave the sales office, take a look around outside to see if there is, indeed, a waterfront and whether or not the operation looks well run or otherwise.

Again, these are not absolutes. Compare as you go from dealer to dealer. Use your eyes and common sense. Find out if there is a year-round, full-time employee solely responsible for yard operations or if the operation is strictly seasonal: you may want something done on your boat in the middle of winter.

1 What Is Covered and for How Long. XYZ Yachts warrants all boats and parts manufactured by it to be free from defects in material and workmanship under normal use and circumstances and with normal care and maintenance for a period of 12 months from the date of delivery to the original consumer.

2 What Is Not Covered. This warranty does not apply to:

a Paints, varnishes, gel coats, chrome-plated or anodized finishes, and other surface coatings.

b All installed equipment and accessories not manufactured by XYZ, including, but not limited to, engines, pumps, batteries, heating, refrigeration and plumbing equipment, and stereo equipment.

Where possible, however, all warranties furnished by these component part manufacturers will be passed on to the consumer.

3 Under What Circumstances Will the Warranty Not Apply. There will be no warranties whatever:

a Where the boat is altered or repaired by persons unauthorized by XYZ.

b Where a hydraulic backstay adjuster is installed.

c Where rigging changes are made, unless first approved, in writing, by XYZ or made at the XYZ factory.

4 Where and How Are Warranty Claims Made. All warranty claim notifications must be made through an authorized XYZ dealer within 30 days after discovery of the defect. An inspection may be made within a reasonable time by an authorized representative after receipt of the claim notification. When a warranty claim is valid, XYZ or its authorized representative shall have the option of either replacing and installing, or having installed, the defective component part or requiring that the part be returned for repair or replacement to XYZ. Claims for reimbursement, if any, must be submitted upon their completion on the standard XYZ Warranty Service Claim form, available either from the dealer or from XYZ Yachts.

5 Limitation on the Length of Implied Warranties. The implied warranties of merchantability and/or fitness for a particular purpose are limited in duration to the period of 12 months from the date of delivery to the original consumer.

6 Other Important Information:

a XYZ does not, under any circumstances, assume responsibility for the loss of time, inconvenience, or other consequential damages, including, but not limited to, expenses for transportation and travel, telephone, lodging, loss or damage to personal property, or loss of revenue.

b Cracks in finishes which might appear at the hull-to-keel ballast joint are normal and should not be considered as evidence of defective workmanship or material.

c Leaks at stanchions and chain plates resulting from day-to-day operation of the boat are normal and considered part of consumer maintenance.

d XYZ reserves the right to make changes in the design and material of its boats and component parts without incurring any obligations to incorporate such changes in units already completed or in the hands of Dealers or consumers.

e The entire obligation of XYZ regarding the sale or rental of its boats is stated within this written warranty. XYZ does not authorize its Dealers or any other person to assume for it any other liability in connection with the sale or rental of its boats.

f Section 15 of the Federal Boat Safety Act requires boat manufacturers to obtain certain data from the purchasers of its products. We cannot fulfill our obligation under this important Act without your cooperation. Would you, therefore, please complete the Warranty Registration Certificate accompanying this warranty and return it to us as soon as possible. If you need assistance in completing the card, please check with your XYZ Dealer or contact us directly and we will be glad to assist you.

In 1975 the US Congress passed a law to help consumers – all consumers, even the boat buyer. It is known officially as the Consumer Product Warranties Law, although it is also known by the name Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, after the men who sponsored it. Its purpose is to regulate consumer product warranty practices; thus, it applies almost exclusively to new boats. The Federal Trade Commission has the responsibility for enacting rules under the law and enforcing compliance. Its first rules were issued at the end of 1975 and became effective during 1976.

What warranties does the manufacturer give when purchasing a boat?

As we are all aware, manufacturers have utilized many different varieties of warranties over the years, some good and some bad. Some were so complicated that consumers couldn’t understand them, some required specific affirmative behavior by the consumer to avoid forfeiture of his rights, and others just started out worthless.

Reputable manufacturers usually gave fair warranties and honored them. Others wrote beautiful warranties and never intended to honor them; the warranty was simply a sales tool. The new law hopes to end the abuses.

However, its requirements are strict and could cause even the best manufacturers to cut back on their warranties. If that happens, at least you’ll know before you buy that your new boat has a weak warranty. Of course, if something not covered occurs, the reputable builder may fix it free anyway if it’s clearly his fault, but the decision will be entirely his, not yours.

Here are details. There are two basic types of warranties, those called «full» and those called «limited». A written warranty must be either one or the other. The designation should appear prominently as a title, set apart from any text at the top of the warranty document. Most warranties are limited, because a full warranty must meet tough minimum standards under the law. It’s also possible for a complex product like a boat to carry both full and limited warranties, each applicable to different features of the boat.

Basically, under a full warranty, the manufacturer must promptly repair or, if that isn’t feasible, replace any item covered. All the consumer has to do is notify the manufacturer, and the warranty must tell him how to do this. There can be no charge to the buyer.

The warranty must state its duration, which must be «reasonable», taking into account the nature of the product. In addition, using reasonableness as a guide, a full warranty has a provision to force replacement or even refund of a «lemon». One reason why manufacturers will probably avoid issuing full warranties is that there can be no limitation on the duration of an «implied warranty» under a full warranty.

Read also: How to Purchase the Perfect Boat: Evaluation to Final Sale

An implied warranty, for those of you who didn’t bother to become lawyers, is based essentially on the assumption that a product is suitable for the purpose for which it is sold. For instance, regardless of whether or not you get a written warranty – or even a promise from a salesperson – there is an implied warranty that your new boat will float, that it won’t leak huge quantities of water through its deck, and that its chain plates won’t pull out under normal use in a light breeze.

But, because sooner or later anything wears out, a manufacturer isn’t unreasonable if he issues a limited warranty, because he then can limit the duration of any implied warranties to the duration of the limited warranty. That duration, though, must be reasonable.

The new law requires that a limited warranty clearly spell out what is covered and what is not. The manufacturer, however, cannot disclaim basic implied warranties because a provision of the law restricts limitations to those which are «conscionable».

All warranties must be made available to you to read before you commit to buy. This right can be of great value to you if you take advantage of it. Read and compare warranties, just as you compare any other feature of the boat. You’ll get a good idea of which builders talk straight and want to be fair and which ones are concerned only about selling. You’ll also have a standard against which to measure your salesperson’s sales pitch.

If there’s an inconsistency, believe the warranty, although, as I mentioned above, the good manufacturers (encouraged by ethical dealers) in extreme situations may do what’s right regardless of any warranty.

Documentation

Briefly, to document a boat is to register it with the federal government instead of a state government. You do this by filling out specific forms, which are obtainable from the United States Coast Guard. The United States is divided into a number of Coast Guard districts and you normally register your boat with the headquarters of the district in which you live.

The advantage of documenting your boat is that it gives you the clearest possible proof of ownership. This is practically a necessity if you are ever going to sail your boat to another country; its customs officers are going to want to be sure you are not in a stolen boat.

Then, too, when you sell the boat, the buyer can be confident he has clear title because the Coast Guard maintains a file on a documented vessel and anyone who has a lien on the boat, such as the lending institution who financed the boat for you, will be on record. Thus, a buyer merely has to check with the Coast Guard to satisfy himself that he is going to purchase a boat free and clear.

Minor advantages of such documentation are that you do not have to clear US customs if you are leaving for, say, Bermuda or the Virgin Islands. Also, you do not have to paint registration numbers on the bow of How to Choose the Best Selling Price for Your Boatyour boat, something that many people – including me – find objectionable on aesthetic grounds. No matter what you hear to the contrary, documentation, per se, will not allow you to evade sales tax.

If you are buying a new boat, the process is fairly simple and documenting it is probably the thing to do – if the boat qualifies. Anyone lending you money to buy the boat is going to want to have the boat documented as part of the financing arrangement, for the reasons given above.

To qualify for documentation, certain of the measurements of the boat are fed into a formula. The boat can be documented if the formula produces a number of five or larger. The formula is this: overall length of the boat times its greatest beam times depth from deck to top of ballast, if ballast is external (or bottom of keel if ballast is carried inside), times 0,0045.

This yields the theoretical internal cubic volume of the boat in hundreds of cubic feet. To qualify for documentation, the boat must have, by formula, 500 cubic feet of internal space. Each 100 of these cubic feet is called, because of tradition, a ton. A boat whose measurements, when put into the formula, produce a number of, say 9, is said to «measure» 9 net tons.

Now, this obviously has nothing whatever to do with the weight of the boat. These «tons» are cubic feet of air space. So do not think that if, for example, you buy a documented boat measuring 10 net tons she weighs 20 000 pounds. I mention this because it is a very common belief that tonnage measured and expressed in this way does represent the weight, or displacement, of the boat.

The mechanics of documentation are fairly straightforward. The builder of the boat fills out a form called the Master Carpenter’s Certificate. This basically states that the company built the boat and also states for whom the boat was built. In the case of a stock production boat, this will normally be for the dealer from whom you ordered the boat: you ordered the boat from the dealer and the builder constructed the boat for the dealer to sell to you. The Master Carpenter’s Certificate also shows the twelve-digit serial number, which is molded into the transom, and the measurements needed for the formula.

When you have paid for the boat, the dealer gives you two identical, notarized bills of sale on a special Coast Guard form, which states, basically, that he has sold you boat Number So-and-So, as described in the Master Carpenter’s Certificate.

You take the Master Carpenter’s Certificate and the bills of sale and contact the officer in charge of the Coast Guard district in which you are going to register the boat.

You then fill out a form swearing that you are a United States citizen and a form in which you designate a name for the boat; a permanent, unique number is assigned to your boat.

This is her number from then on. It never changes, no matter how many times she is bought or sold or in what other districts she comes to be registered as the result of those sales.

It is your responsibility to see that that number is permanently affixed to the inside of the boat. In a wooden boat, this is normally done by carving the numbers into the main deck beam. In a fiberglass boat, this is normally done by carving the number into a teak board and then screwing and/or gluing the board into the boat.