The Lusitania sinking was a significant event during World War I. The Lusitania was a British ocean liner that was torpedoed by a German U-boat, U-20, on May 7, 1915. The ship was en route from New York City to Liverpool, England, when it was attacked off the southern coast of Ireland. The attack led to the deaths of 1 198 of the 1 959 people on board, including 128 Americans. The sinking of the Lusitania played a crucial role in shifting public opinion in the United States against Germany, contributing to the U. S. eventually entering the war in 1917. The Germans justified the attack by arguing that the Lusitania was carrying military supplies, which it was, though it was primarily a passenger vessel.

The incident sparked outrage and was used by the Allied powers as propaganda to gain support for the war effort. The Lusitania’s sinking remains a poignant symbol of the dangers of unrestricted submarine warfare and the broader human cost of World War I.

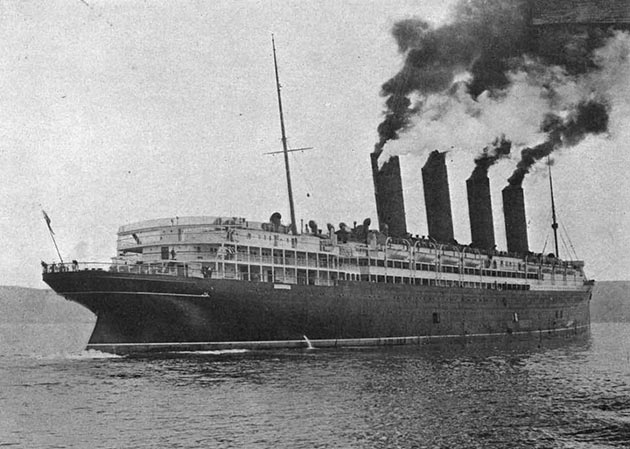

June 7th 1906 was a perfect summer’s day as thousands of visitors streamed into the famous shipyard of John Brown and Company Limited. Anticipation among the crowd was high on that Thursday morning. Situated on the north bank of the River Clyde in Scotland, the shipyard had been a hive of activity for the last two years. Thousands of men had been employed on building a single ship which, as the crowd amassing for today’s launch would witness, was about to take its place as one of the most technologically advanced passenger liners in history, boasting the very best in design and comfort. Christened Lusitania, after the ancient Roman province on the Iberian peninsula, she held the distinction of being the largest ship in the world. The local press were in their element.

Final Voyage

It was just after 12.20 p.m. on 1 May that Lusitania backed into the Hudson River, a moment caught on film by the newsreel cameraman. Passengers waved handkerchiefs and flags as the huge ship was nudged into position by tugs and steamed off towards the open sea. Archie Donald stood on deck and observed proceedings.

We passed down the Hudson in the afternoon and gazed at the wonderful sky line of New York City, passing the Statue of Liberty about 2 o’clock. We were soon out to sea and at the 3 mile limit were stopped by the cruiser Caronia, which took off their mail and papers. In the distance we saw the cruiser Essex and the battleship [sic] Bristol.

Mr Donald would not have been aware that HMS Caronia, previously a Cunard liner but now converted into an armed merchant cruiser, received a more interesting delivery than just mail. A camera, accompanied by an explanatory report written hastily by Captain Turner, was also handed over. This related to three German stowaways who had been found on Lusitania shortly after her departure. It is likely that the men were attempting to find and photograph evidence of the ship being armed, yet had been caught in the act. The three Germans remained on board Lusitania but were kept locked up in a cabin, the intention being that they would be properly interrogated after arrival on British soil.

As for the ship’s legitimate paying passengers, they now had the opportunity to stroll around the decks and make the acquaintance of their fellow travellers. Popular places to frequent were the dining rooms and saloons of the ship, while regular entertainments were arranged by both crew and fellow passengers in order to ensure that the voyage would be as carefree and comfortable as possible, as Archie Donald could attest.

The voyage was the most wonderful and most pleasant I have had, each day was fine with the sun shining, and I never missed a meal, or the time never seemed to hang heavily on our hands. We did not read our New York papers until the afternoon of the first day, and in it we saw the warnings of the German Embassy in large type; however, it was too late to read the warnings when on board ship, and the confidence we had in the speed and carefulness of the Cunard Company allayed any feelings of un-safety.

On board I made the acquaintance of a Mr Thornton Jackson of Heswell, and we found many mutual acquaintances. He was one of the nicest men I have met in recent times, being an acute businessman and a thorough gentleman. Wilson and Jackson played against Mr Gwyer and myself at Auction Bridge, and every morning about 10 o’clock we used to meet in the top lounge and while away the morning. In the afternoon we wrote letters or went and spent the time amongst the ladies, and also in the evening we resumed our games at Bridge. The company was most pleasant and the time sped quicker than ever I have found it to do so at sea.

Stewardess May Bird had been serving on Lusitania since the ship’s maiden voyage, and was therefore already more than familiar with the ship’s opulent facilities. The size of the vessel and the number of passengers milling about meant that it almost resembled a small town.

The Lusitania, that was my first ship. She was in those days the biggest ship in England. The accommodation, of course, was wonderful. I’d never seen anything like it before. There were:

- big;

- airy;

- well-ventilated;

- well-heated;

- beautifully furnished and big rooms and little rooms;

- both kinds.

And it took a long, long time to walk from one end of the ship to the other, I should say nearly 20 minutes.

Children had the finest times of their lives, there were all sorts of deck games, Quoits, they had fancy dress parades for them, and if a child happened to be on board and it had a birthday, there was always a birthday cake made with their name on and they used to give them a little private party. They had the time of their lives and the run of the ship.

The comfortable surroundings and calmness experienced once the ship was under way encouraged many passengers to forget about the war completely. While the submarine threat was ever-present, it seemed increasingly unreal to think that such a danger could threaten this remarkable vessel. First-class passenger Ambrose Cross shared such an optimistic attitude.

Of course, I thought there was a sporting chance that we might not get to Liverpool, but one must take chances nowadays. However, I was astounded to find the ship full of rank, fashion and wealth, and big crowds in the second and third. From the very first the ship’s people asserted that we ran no danger, that we should run right away from any submarine, or ram her, and so on, so that the idea came to be regarded as a mild joke for lunch and dinner tables. There was a lot of money on the ship, in the saloon as well as in the hold. The pool on the ship’s run used to average £105, and on our last night on the ship there was a brilliant gathering (seems ghastly to think of it now) at a concert when £123 were collected for the Liverpool Seamen’s Orphanage.

The weather during the next few days at sea caused a small amount of seasickness among some passengers, but the vast majority soon made themselves at home. Passengers played cards or read books in the various lounges, composed letters home, or took afternoon tea in the garden-like cafe filled with shrubs and hanging baskets of flowers. One of the most common pastimes was to sit in a deck chair, wrapped in a warm rug, and watch the Atlantic as it swept past. The other chief interest for passengers was food and drink, with a massive variety of high-quality food available. First-class passengers in particular experienced a world-class dining experience, while the amount of alcohol and tobacco on board was plentiful to say the least. It was not uncommon for wealthy businessmen to spend the majority of the voyage in the ship’s first-class smoking room.

The second-class cabin allocated to Preston Prichard was D90, situated on the port side towards the stern of the vessel. His cabin was a short walk from the Second Cabin dining saloon and adjacent to the ship’s barber shop. Every time that he left or entered his room over the next few days, Preston would greet the barber, Jonathan Denton, and they would often share a chat. Denton himself had only joined the ship’s crew at the last minute, taking the place of another man who happened to have fallen ill.

As the voyage progressed, Preston participated in many of the activities arranged in order to keep the ship’s passengers entertained, frequenting the music room and being particularly active in organising whist drives and betting pools. Thomas Sumner, the fellow amateur photographer whom he met shortly before the ship left New York, described Preston as … such another fellow as myself. As we were both travelling alone we met practically every day … He always seemed very pleasant and enjoyed himself in a very quiet manner – you will understand what I mean, he didn’t go about in a rowdy fashion like lots of fellows do when having a time. He took part in the sports, I remember him in the obstacle race and the tug o’war.

Fellow passenger Olive North was returning home to Yorkshire after having spent time visiting her married sister in Canada. She recalled seeing Preston many times on deck, and on one particular occasion he took advantage of his experience on the Canadian ranches in order to entertain his fellow passengers.

A party of us used to have a game of skipping every day. One of the boys tried to lasso me […] but did not manage to do it very well, so this young gentleman had been watching us, came forward and said, «I will show you how to do it». He seemed to be an expert on lassoing and caught quite a few in the rope. When he handed me the rope back he remarked that he had lassoed before.

On the second day out from New York, third-class passenger George Hook also encountered Preston. Hook’s wife had passed away some eighteen months before, and George had decided to take his family, consisting of daughter Elsie and son Frank, to relocate to a new life back in his native England.

I had took my daughter up on to the second class deck and she went to sleep there and [Preston] came along and said, «Your little girl looks very ill», and asked if I had a rug to put over her as she ought to be covered up. I told him mine was at the other end of the ship, so he went and fetched his and wrote on an envelope his name and number of his cabin so as I could take it to his cabin when I had finished with it. I can remember what a job I had to find his cabin when I took it back.

During each day of the voyage Captain Turner ordered fire drills and tests of the ship’s watertight bulkhead doors. In addition, every passenger was allocated their own lifejacket, usually stored in their cabin. All passengers were expected to attend a lifeboat drill, in which the ship’s crew demonstrated the procedures to follow in case of an emergency but, as Jane Lewis recalled, such drills were rudimentary to say the least and only really intended to reassure the passengers. They were certainly of little value as a training exercise for the crew. But such things proved an amusing diversion to pass the time.

Oh yes, we had to go through a practice, put lifebelts on, that’s all – stand all on the deck so many at a time. That’s how we got to know how to put [the lifejackets] on. Oh yes, they were all put out just after we left [New York]. It was well looked after, that was, very well looked after.

Stewardess May Bird had already experienced submarine scares during earlier voyages in Lusitania.

On the way home from New York [on a previous trip] we were stopped just outside Queenstown. Rumours got around all about why we were stopped, and so forth. The war was on. And eventually we were taken into Queenstown and not allowed home or [to] write letters and we were under strict orders. We were kept there for a week. And the reason was that at that time they had torpedoed a pilot boat off the bar and the pilots were drowned, and they were there waiting for us. And that’s why they didn’t let us go up to Liverpool, they turned us into Queenstown.

For this particular voyage, an added precaution was put into operation.

The only difference from any other voyage was that we had to be very particular, no lights shown on deck. Not even a match struck. And all the windows, port holes and everything had to be covered, which of course was done. We’d had the normal lifeboat drill, but we always did have that, so that wasn’t special, that’s the usual thing – everybody on board knew which was their lifeboat. The number and which side of the deck they had to go to.

The attitude of many people towards the possibility of a submarine attack was perhaps best summed-up by Ambrose Cross, whose pragmatic attitude would stand him in good stead in the days to come: «I had formulated no plan of campaign except a vague notion that if anything happened I would go right out and not wait to pick up anything; this I did, and it probably saved my life».

Lusitania was full to capacity with second-class passengers and Preston Prichard shared his cabin with three other men, including Arthur Gadsden, a British civil engineer from Northamptonshire who had been living in Chicago. The subject of the war, and in particular German submarines and the inherent dangers present during their voyage, often came up as a topic for discussion.

I can assure you he was most anxious to be home again and was counting the time when he would arrive … [Preston] was quite aware we were in the danger zone because we were talking about submarines and wondering if we should see one at all, never having the least fear but that we should get away from them.

Preston also befriended the ship’s wireless operator, Robert Leith.

We had several long conversations during the trip, and [I] found him very interesting indeed. If I remember correctly our topic was that of the war, and once or twice of submarine attacks. […] His health at that time as far as I could perceive was excellent, and in high spirits (no doubt at the thought of returning home).

Unknown to those on board Lusitania, events were already in motion which would lead to a fateful encounter. The German submarine U-20 had sailed on Friday 30 April from the naval base at Wilhelmshaven, captained by the 29-year-old Walther Schwieger. Having joined the Imperial German Navy in 1903, Schwieger had served in U-boats since 1911 and by 1915 was therefore something of an experienced submariner. His orders on departure were to follow a route north around Scotland before reaching his target patrol area in the Irish Sea around Liverpool. He was to look out for:

- British troop transports;

- merchant vessels and warships;

- holding his position for as long as fuel and supplies permitted.

Instead of following the fastest route, which would have taken U-20 along the Scottish coast and then down towards the Irish Sea, Schwieger chose to sail around the west coast of Ireland, this being the safer course. The U-boat dodged patrolling British destroyers, while an attempt to sink a steamer on 3 May was thwarted due to the torpedo remaining wedged in its tube. A further attack the following evening was abandoned when Schwieger was able to identify his potential target as the Swedish cargo ship Hibernia, displaying neutral markings.

As U-20 had progressed around the northern coasts of Scotland and Ireland, no fewer than fourteen separate transmissions had been intercepted by the Admiralty’s Room 40, in which Schwieger established his position. By the Wednesday morning the submarine was therefore identified as heading south along the western coast of Ireland, towards Fastnet, the most southerly point of land. Also present off Fastnet was the cruiser HMS Juno, intended as the escort ship to Lusitania, which was expected in two days’ time. The obvious threat of a U-boat attack on a lone ship led the Admiralty to recall the cruiser to Queenstown immediately. Crucially, no message was sent to Lusitania, either to warn the crew of the submarine approaching the danger zone through which they were scheduled to sail or to inform them that their escort was no longer available.

Arriving off the south-west coast of Ireland on the afternoon of Wednesday 5 May, U-20 sighted a new potential target, as described in Captain Schwieger’s log.

16.50 hrs: I head for a sailing vessel which appears to be of large size. On approaching I find that it is only a small three-master. As there is no danger of any kind to U-20 I bear away aft of the sailing vessel. The crew consisting of five men are ordered to abandon ship and to come alongside in order to hand over the flag and the ship’s papers. The vessel is the Earl of Latham. It was on a voyage from Liverpool to Limerick carrying a cargo of stone. We sink it by means of twelve shells from the rapid-fire cannon. The crew ply their oars in the direction of the coast despite the fact that there is a fishing boat in the vicinity.

This occurred just off the Old Head of Kinsale, a notable headland in County Cork which was the first and last landmark traditionally seen by transatlantic ships. U-20 then proceeded eastwards along the coast, and towards midnight attacked the British steamer Cayo Romano off Queenstown.

20.10 hrs: I attack a steamer of around 3 000 tons with a bronze torpedo. The steamer stops, alters course and continues at full steam ahead as soon as it sees the air bubbles of the torpedo wake. The torpedo grazes him aft. I was really under the impression that towards the end the torpedo became maladjusted and was no longer advancing. The steamer does not stop zigzagging in order to escape from a second torpedo and I desist from making a further attack.

Once news of both attacks reached the Admiralty, they ordered a signal to be sent to all ships warning «Submarines active off south coast of Ireland». This signal was surprisingly vague, considering that the attempt on Cayo Romano had given them a specific location only a few hours out of date.

By the next morning, that of Thursday 6 May, Schwieger had reached the vicinity of the Coningbeg Lightship which marked the entrance to St George’s Channel and the final approach to Liverpool. There, U-20 encountered the British steamer Candidate.

07.40 hrs: Intermittent thick fog. Emptied the water ballasts in view of brighter weather and continue course on surface. A large steamer reported ahead to starboard. I run in for a surface attack. No danger to us of being rammed or fired on in poor visibility conditions such as these. The steamer puts about after sighting U-20. To continue on the surface does not appear to me to be dangerous in this fog. I maintain the helm dead on the steamer and attack with cannon fire. The steamer flees at full speed. After having been hit twice it disappears in the fog for some time. When the target again becomes visible I resume my cannon fire. The steamer does not cease pointing its stern towards us in order not to be torpedoed. Not until having been hit several times (once by a full hit on the bridge) does he stop and lower his boats to the water. One of the boats fills with water and sinks as soon as it is released by the tackle. The three others depart heavily overloaded.

10.00 hrs: The three lifeboats turn away slowly from the steamer. I fire from the forward tube (bronze torpedo set for two and a half metres) at a range of 500 m. The torpedo strikes at the height of the engines without great effectiveness. The steamer sinks a little at the stern but stays afloat. Seeing this I approach and give the order for fire to be opened onto the load water line with the rapid fire cannon. The name painted on the stern and covered by a layer of paint is Candidate of Liverpool. The steamer is of 5 000 gross tons. It had no flag hoisted.

10.25 hrs: It dips lower and lower and then sinks whilst see-sawing with the stern largely above the water line.

Only ten minutes later, the White Star Line passenger ship Arabic was sighted and U-20 dived and raced into a position for firing. Unfortunately for Schwieger, the liner was moving at full speed and still too far away for him to target a torpedo properly. He therefore let the ship get away, no doubt frustrated that such a large and impressive vessel had escaped him. However, barely an hour later, U-20 sighted another potential target and intercepted Candidate’s sister-ship, Centurion. Acting cautiously on the fair assumption that the merchant vessel was armed in the same manner as her sister, Schwieger fired two torpedoes and sank her. U-20 could now boast three definite victories, but their fuel was running low and they had yet to reach the intended target zone off Liverpool. By the Thursday afternoon, Schwieger had therefore decided on a revised course of action.

14.15 hrs: Thick fog. Submerge to 24 m and follow course 240 degrees in order to keep to the open sea. I forgo approaching Liverpool any nearer – despite the fact that the landfalls here are indicated to be operational bases – for the following reasons:

- Because of the fog which has been in evidence throughout these two days of calm and because the barometer reading does not permit me to predict an early brightening up.

- Because during the time of fog it is impossible to make out in time the numerous enemy surveillance ships in the St George’s Channel and the Irish Sea, i. e. trawlers and destroyers. In these circumstances and having to navigate submerged all the time.

It would be out of the question during nights with little visibility to await the passage of convoys coming out from Liverpool for it would be impossible to find out whether they are or are not escorted by destroyers. Moreover it is to be expected that they are always escorted, particularly at night.

Source: wikipedia.оrg

In the course of the outward-bound voyage from Emden to the St George’s Channel the consumption of fuel has already been so great that a return journey from Liverpool doubling the south of Ireland would no longer be feasible, and I want to avoid at all cost a return journey through the North Channel because of the well established surveillance at the height of the Firth of Clyde, the effectiveness of which U-20 has already had the opportunity of experiencing on an earlier cruise.

And finally, I have only three torpedoes left at my disposal. Of these I want to keep two for the journey home.

Therefore I have taken the decision to cruise to the south of the Bristol Channel and there to attack steamers until two-fifths of my fuel supply is used up. In that area there will be no lack of opportunities for carrying out attacks and there will be less danger of reprisals.

Meanwhile, Lusitania was sailing on towards her destination. Throughout the voyage the war had manifested itself in various ways, some unexpectedly so. A concert held on 3 May had led to some controversy when passengers complained in a very public manner about the choice of «unpatriotic» music by Johann Strauss. Captain Turner had also had to deal with some disquiet among passengers who were expressing concern over the brevity of lifejacket and lifeboat drills, leading him to address such criticisms directly via a question and answer session in the first class dining saloon. By this time, on the evening of Thursday 6 May, the ship was nearing the danger zone. As the liner approached the waters off the southern coast of Ireland where U-boats might be lurking, Archie Donald recalled how the ship’s crew implemented additional safety procedures.

On the Thursday night we ran into a bank of fog and our log showed we were approximately 200 miles from the coast of Ireland; the fog horn went all night, and I believe a boat drill was given to the men who swung out the lifeboats on the «A» deck. However, they did not tear off the cover of canvas on the collapsible boats, which were piled on the aft saloon decks in groups of three, there being four groups or twelve of these collapsible rafts in all. In the morning when we got up we noticed the boats were out but thought it was just a precaution, and no fear was felt.

Alice Lines also remembered how the Thursday evening saw safety measures instigated. This may have been a direct result of Captain Turner responding to the signal sent by the Admiralty, warning in general terms about submarines being active, or could equally have been just a sensible precaution in time of war.

That evening before, they did come and close the port holes. The steward came and said that he’d had his orders to close them. Until then I mean there was no thought of war or anything. As far as I, a young girl, I was enjoying myself. I was going to the dancing, I’ll be quite honest I was having a good time. War was … well, you don’t understand it until you get into it.

Shortly after midnight, Lusitania received a further Admiralty message, addressed to all British ships: «Take Liverpool Pilot at bar and avoid headlands. Pass harbours at full speed. Steer mid-channel course. Submarines off Fastnet». To Captain Turner, this meant that he was allowed to take Lusitania straight into Liverpool without having to wait outside for a pilot, which would have left his ship in a dangerous, predictable position. The best time to arrive at Liverpool would be 4.00 a.m. on the morning of Saturday 8 May, as this would be high tide while coinciding with his schedule of making port at dawn. A new course was therefore set, avoiding the danger zone off Fastnet by at least 20 miles while sailing in complete darkness.

The next morning, the Friday, passengers on board Lusitania awoke to find the ship surrounded by a bank of dense fog. Visibility was reduced to 30 yards. While this was good news for Captain Turner, since any U-boat would struggle to find a target in such conditions, it also posed a problem – he was supposed to meet up with his escort cruiser HMS Juno, yet the fog made this very difficult indeed. Turner was still unaware that Juno had been recalled to Queenstown. He therefore ordered that their speed was to be reduced to 15 knots and the foghorn sounded regularly. Meanwhile, as its log attests, U-20 was lurking outside Queenstown.

09.00 hrs: As the fog has not lifted I decide to start on the home journey with the purpose of engaging myself in good time in the North Channel.

10.00 hrs: Bright spell. A trawler (patrol boat?) sailing towards me from the direction of the land. He is still far away.

10.05 hrs: Have submerged to 11 m and observed steamer. Suddenly visibility excellent. Steamer’s speed is low. Nevertheless I submerge to 24 m and bear off from him. I shall rise again to 11 m towards 1 300 hrs in order to examine the vicinity.

11.50 hrs: Visibility very good. A ship with very powerful engines passes above us. When I rise to 11 m again I establish that the ship which passed above us ten minutes earlier is none other than a British man-of-war, an old small cruiser (of the Pelorus class) with two masts and two funnels.

This was in fact Lusitania’s escort, HMS Juno, following her orders to return to port.

12.15 hrs: I chase the destroyer in order to try to attack her when she alters course. But she does not cease zigzagging in every kind of way and at all speeds and, finally, disappears in the direction of Queenstown.

12.45 hrs: Visibility very good; very fine weather. Therefore I have emptied my water-ballasts and have continued on my course. It seems useless to be waiting in the offing of Queenstown.

As the submarine rose to the surface and headed west on its journey back around the Irish coast, Lusitania was nearing the same location. Once the fog had cleared just before 11.00 a.m., the liner had increased her cruising speed to a steady 18 knots so as to arrive at Liverpool at the expected time, while Turner ordered that the ship’s steam pressure should be kept high in case he required an extra burst of speed in the event of sighting a submarine. To port, the coast of Ireland could be seen in the hazy distance.

Unknown to those aboard the Lusitania, the loss of the two steamers Candidate and Centurion was giving those on land particular cause for worry. Just as Lusitania cleared the fog bank, a signal was received which warned that there was a «Submarine active in southern part of Irish Channel, last heard of twenty miles south of Coningbeg Light Vessel. Make certain Lusitania gets this». This signal is likely to have been the direct result of a plea from Alfred Booth, the Chairman of Cunard, who rushed to the naval authorities on the Friday morning in order to ask them to send a particular warning to Lusitania, alerting her of U-boats operating on her intended course.

Rather than helping Lusitania, this message simply raised questions in the mind of Captain Turner. The previous message he had received advised him to «steer mid-channel course», yet this new warning indicated that the submarine threat was exactly in that position, in the middle of St George’s Channel. He therefore decided on a new plan of action – he would enter the narrowest northerly portion of the Channel, albeit contravening Admiralty instructions, yet ensuring that he avoided the spot where submarines were reported to be waiting. A new course needed to be set. At about 1.30 p.m Turner altered Lusitania’s heading by 20 degrees to port, in a manner so sudden that some passengers lost their balance, and headed towards land. His intention was to establish the ship’s exact position by sighting landmarks, and ten minutes later the Old Head of Kinsale could be seen in the distance. Now that he had his bearings, a safe course could be plotted through the minefields to avoid the submarine danger zone. What Captain Turner had no way of knowing was that U-20 was actually heading west towards him on a direct course, only twenty minutes away.

For Lusitania’s passengers, lunchtime on that Friday was like any other. Preston Prichard had proved an entertaining dinner companion throughout the voyage, with his good humour and handsome features attracting a number of young ladies including the shy 25-year-old Alice Middleton who sat near him every day in the Dining Saloon («if I happened to be looking that way, he would nod to me, but we never got a chance to speak somehow»). There was also Grace French, with whom Preston appears to have struck up a definite friendship. He shared a table with her at mealtimes and as such saw her regularly, at least three times each day. Grace, originally from Scotland, had spent the last four years staying with her brother in New York City.

I can see his face so clearly in my mind, so sunburned and full of life and ambition. He kept us in good spirits relating different experiences he had during his travels and was very nice to everybody. I appreciated his efforts as I was very sick during the whole journey and [he] was especially nice to me.

Grace and Preston would share a final encounter together at the first lunch sitting on 7 May. With the coastline of Ireland just emerging into view, the end of their voyage was fast approaching. For both passengers, lunch together would prove to be the last touch of normality on board the ship before chaos erupted.

Sinking

Braced against the conning tower of U-20 where he was likely appreciating the novelty of fresh air and sunshine, Captain Schwieger would have been close enough to see the Irish coast as his submarine sped on its course. Suddenly a potential target appeared on the horizon.

13.00 hrs: Dead ahead there appear four funnels and two masts of a steamer on a course perpendicular to ours (he had been coming from the south-south-west and heading for Galley Head). Ship is made out to be a large passenger liner.

13.05 hrs: I submerge to 11 m and make full speed in order to cut off the steamer’s route in the hope that he would cast to starboard with the intention of hugging the Irish coast.

13.07 hrs: The steamer turns to starboard and takes a course heading for Queenstown which makes my attack feasible. I was forced to make great speed up to 1 400 hrs so as to reach a propitious position right ahead of him.

14.10 hrs: Fire from tube at range of 700 m (G torpedo adjusted to 3 m). Angle of incidence 90 degrees. Probable speed 22 knots.

On board Lusitania, eighteen-year-old Leslie Morton was on duty as a lookout. Leslie had worked at sea since the age of thirteen but now, keen to serve his country in the war, had decided to return home to Britain with his brother, Cliff. Both young men were working their passage home in Lusitania. Wartime precautions had led to the introduction of an increased watch when in danger zones, in order to give as much advance warning as possible of a potential attack. Morton had just begun one of these extra 2 hour shifts that afternoon, at 2.00.

My position was in the eyes of the ship. My particular section was the starboard bow, from right ahead to abeam. There were four of us on the lookout, altogether, covering the whole area. It was a beautiful day, the sea was like glass. And as we were going to be in Liverpool the next day everybody felt very happy. We hadn’t paid a great deal of attention to the threat to sink her because we didn’t think it was possible. The first ten minutes I walked up and down, keeping a keen lookout, and 10 past 2 I saw a disturbance in the water, obviously the air coming up from a torpedo tube, and I saw two torpedoes running towards the ship, fired diagonally across the course, and the Lucy was making about 16 knots at the time. I reported them to the bridge with a megaphone we had, to say «Torpedoes are coming on the starboard side». And by the time I’d had the time to turn round and have another look they hit her amidships between number 2 and 3 funnels. Unfortunately the torpedo, one of them, went through the luggage room where the whole of the starboard watch who’d left 15 minutes before were working, getting out luggage. So in that one foul swoop we lost the whole of the starboard watch of seamen for the necessary work that had to follow soon on the boat.

Leslie Morton remained certain that he had witnessed the wake of two torpedoes, but only one had actually been fired. This erroneous observation, shared by a number of others who witnessed events that day, was most likely influenced by the two explosions that subsequently occurred:

- one caused by the immediate impact of the torpedo;

- with a second explosion happening almost immediately afterwards.

Other crew witnessed the torpedo heading towards the liner and tried to raise the alarm. Steward Robert Chisholm happened to be on the starboard side of the ship’s «B» deck at 2.10 p.m.

I was looking over the side. I saw the wake of the torpedo as it approached the ship. The torpedo was about one hundred yards away when I first saw it. I immediately ran and told the Chief Steward that there was a torpedo coming. Just as I was telling him, the explosion took place. When the explosion occurred water was thrown up over the deck. «B» deck is about 30 feet over the water line.

As the 350 pounds of explosive detonated against the hull of Lusitania, Schwieger witnessed the effect of his attack through the periscope of U-20.

The torpedo hits on starboard side just aft of bridge. It produces an exceptionally strong detonation followed by a cloud of smoke (at great height above the first funnel). To the explosion of the torpedo there must have been added a second explosion (boiler, coal or powder?). The superstructure and the deck above the point hit are cut to bits. A fire breaks out. The upper bridge is encompassed with smoke. The ship stops immediately and lists strongly to starboard while settling dangerously in the bows. It looks quite as if in a state of capsizing at any moment.

At the time of the attack, the second sitting for lunch was just coming to an end. Many passengers had therefore just finished their meals and were strolling about on deck taking the air, or perhaps finishing their desserts down below in one of the large dining saloons. First-class passenger Wallace Phillips had just risen from the dining table.

I left the dining saloon about ten minutes past two, and should judge that at that time there were possibly one hundred people still at luncheon. Two or three children and one woman came rushing in the open doorway shouting «Torpedo!» and in possibly five to ten seconds it struck. The sound of the explosion, while loud, was not especially terrifying, but the shock was considerable. Almost instantly the boat took a decided list.

Alice Lines, the young nurse entrusted with the Pearl family children, was down below in her cabin when the torpedo hit. Up until this point, the voyage had been a calm and pleasant one for the Pearls and their two nurses, although the fog of earlier that morning had noticeably slowed the ship’s progress. At lunchtime, the twelve-week-old Audrey had been left in their cabin while Alice had taken the other children to the dining saloon. Following their meal, Alice returned down below to feed Audrey, accompanied by five-year-old Stuart. The remaining two children were left upstairs in the care of the other family nurse.

While I was feeding the baby there was a terrific bang. My instinct told me what it was. The boy was lying on the bunk bed and I just picked the shawl up, as she was lying on the shawl, wrapped her in it and tied the corners round her neck. I never thought but just did it. And I crossed over to Stuart and he was crying «I don’t want to be drowned, I don’t want to be drowned», he was just old enough to understand that there was something wrong. I said to him, «Now darling you are going to be alright. Do as I tell you. Hang on to me, never mind what happens. If I fall down, don’t let go». I said, «If you obey me, you won’t drown».

Jane Lewis was at lunch with her family in the second-class saloon on «D» deck, having chosen their table carefully. The saloon was 60 feet in length and ran the whole width of the ship. The tables, which were arranged facing forward and aft in a refectory style, were able to seat some 260 people at a time and at the moment when the initial explosion occurred the room would certainly have been full of the hustle and bustle of chatting diners and busy waiters.

We were just inside the dining room, just inside the door so we could get out quick, because we’d heard rumours something like that might happen. And then when the awful noise came we could just get round the door and on to the landing and down the staircase.

The most vivid scene was when it all first started, when the first explosion came. That was the most real, when people were natural. Everybody was frightened then and panicked. The people came pouring through the dining room from the other part of the ship. People fell down, people walked over them … you couldn’t do anything because the boat was going sideways. And we got out, luckily because we were near the door. Had we not been by that door we would never have got out, because the stream of people that came down the dining room – there were others following at the back – and the people were stepped on and walked on. That was the most terrible thing to me. It was a long time before I could get over that. They just couldn’t help themselves. The crowd was too strong. And I don’t know why we got that seat. Like as if it was fate, just fate. It had to be. Oh, to get out of that dining room was terrible. Well of course it was only a natural thing, wasn’t it, really. Every man for themselves.

Then we went down the stairs. Instead of going up they went down [because of the heavy list to the ship]. And I fell down. [Somebody fell] on top of me on the staircase, and I would never have got down it if my husband hadn’t got hold of me and he had the sense given to him to pull me out.

This sudden rush of passengers, intent on reaching the boat decks where the lifeboats were situated or their individual cabins in order to locate lifejackets, led to attempts by others to maintain order, as passenger Archie Donald recalled. He had just finished lunch in the second-class dining room.

Mr Gwyer, who is 6′ 4″ tall, touched me on the shoulder and said, «Let us quieten the people», so we both rushed up to the door and yelled at the top of our voices that everything would be all right, and that there would be no need of hurrying. The people filed out of that dining room like a regiment of soldiers; there was no trampling, everybody moved quickly, but nobody pushed or shoved. A woman in front of me fainted but luckily her husband was with her, so he took her head and I took her feet, and we managed to get her up the stairs.

Almost instantly after the initial bang, a second explosion had occurred, much larger and more noticeable than the first. Depending on their position within the ship, many passengers and crew found difficulty in distinguishing between the two explosions, with some hardly noticing the first impact of the torpedo. The American passenger Wallace Phillips had just experienced the first torpedo strike when … In a very short space of time … a second one [sic] hit the vessel. I have heard a number of persons say that it was possibly thirty seconds later, but it appeared to be considerably less. The shock of the second explosion was very great indeed, and possibly thirty seconds after it had occurred an immense column of water, carrying with it all kinds of debris, shot up from the side of the vessel.

Meanwhile, Alice Lines and her two charges had just emerged from their cabin when the second explosion happened.

We got up one flight of stairs and there was a terrific bang, the second torpedo [sic]. The nurse was up the top and she called down to me, «What shall I do?» and I said to her «Where is Bunny?» She said a stewardess had taken her to a lifeboat. Now I said, «Well we are all for ourselves, you look after Suzy and don’t worry about anything else – just save the child and yourself».

Following the second, larger explosion on her starboard side, Lusitania began to list dramatically in that direction. Still in motion, the ship was also dipping forward, making the list even more noticeable. Captain Turner immediately ordered the ship to be steered hard to starboard in order to turn them more definitely towards land, the Irish coast being clearly visible in the distance some 14 miles away. It was clear that Lusitania was going to sink and Turner therefore gave the order to abandon ship, yet he had every reason to believe that the liner would remain afloat for some time to allow her passengers and crew the opportunity to escape. In comparison, after striking an iceberg, Titanic had remained afloat for over two and a half hours and Captain Turner had no reason to think that the damage inflicted to his ship would be any worse than that. A minute after the torpedo had hit, Lusitania’s Marconi operator Robert Leith began transmitting an S.O.S. message: «Come at once. Big list. 10 miles south Old Kinsale».

James Baker, a director of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers Company of Newgate Street in London, had been in his cabin on the starboard side of «B» deck at the time of the attack.

I heard a sharp report and cracking sound and the next moment black smoke poured in through the porthole, then a muffled report and very violent vibration, port to starboard, and a list which grew rapidly. I left my cabin, walked to the main staircase and on to the boat deck, port side. The deck was crowded with people and the boats were being got ready. I walked to the end of the deck, under the bridge, and saw that the ship had dipped very considerably and with a list of at least 15 degrees to starboard. I made up my mind that we were doomed, advised people to get life belts and went down for mine. On my return I helped people to put them on.

Within a short space of time, passengers began to assemble on deck and fasten their lifejackets. Lusitania carried 2 325 lifejackets in total, including 125 specially designed for children, along with 35 lifebuoys. The crew, including Steward Robert Chisholm, went into action by ensuring that every passenger had their own life preserver and would be ready to evacuate the ship once the order had been received to launch the boats. Everything appeared to be done in an orderly fashion.

We told all the passengers at once to go to their rooms and get their lifebelts. In every berth there is a lifebelt. There are notes and diagrams in every room showing how these lifebelts are worn. As far as I could see the passengers obeyed our instructions. The stewardesses also gave similar instructions to the passengers. There was no panic. I then went to my own room and got my lifebelt on.

Stewardess Fannie Morecroft also followed her instructions.

There were many of the second cabin gentlemen passengers doing their best to get lifebelts for the women. I myself took some of them into rooms and pointed out where they were, though I think in those few terrible moments few of us recognised one another. Any of the men I saw during that time were just splendid and seemed to have no thought for themselves.

Many passengers had to return below decks in order to retrieve lifejackets from their cabins. With the ship listing to one side and many of the corridors and rooms being in complete darkness due to power failure of the electrical systems, this caused problems for some such as Canadian passenger Robert Williams.

I was on deck when the vessel was struck and my wife was below. I went down stairs, brought her up and made two more trips down below again. I found one lifebelt which my wife used and I went down with the vessel without one and thus lost hold of our little girl. On my last trip down below to look for a second belt I had to climb the stairs on hands and knees as the ship was over at such an angle. There were sufficient belts if one could get down to them. Unfortunately they were all in the cabins and as the ship was so big, difficult to get hold of promptly. I knew many men who were coming over to join up in the war and only know one who survived, and have no doubt that many men gave up their belts to women as some of these men were strong healthy fellows with every prospect of being able to swim clear without a belt on. Many brave unrecorded deeds were done on that afternoon.

Ambrose Cross confirmed the general lack of initial panic.

It was shortly after lunch and there were few people in the big rooms, and anyhow most people were waiting to pick up this, that and the other, no doubt thinking too that there was plenty of time (vide the case of the Titanic). There was hardly any row. The few stewards about were quietly saying that it was «all right», a vague assertion which I found myself repeating to one or two ladies who appeared flustered.

However, from his observation point on the bridge, Captain Turner would have been able to see the immense problems involved in trying to launch his ship’s lifeboats. With the boats already swung out on each side of the vessel, the ship’s dramatic list to starboard meant that those lifeboats situated on the port side had now swung inwards against the hull, making them virtually impossible to launch. The ship was also still moving at a fair speed, making the launch of any boat a dangerous endeavour. In order to allow them to be launched safely, Turner therefore ordered Lusitania’s engines to be put into reverse in order to slow the ship down as quickly as possible. Yet, presumably due to internal damage caused by the explosions, her engines failed to respond. On account of the speed at which the ship’s momentum was still carrying her forward, Turner therefore judged it best to avoid launching the lifeboats for the time being and issued an order to stop any being prepared. For a few minutes, most passengers accepted this and it was not until the list became more noticeable that they began to question the wisdom of simply standing around in readiness. Few realised the danger involved in launching a lifeboat while the ship was still in motion.

Wallace Phillips had proceeded to the boat deck, above which the lifeboats were suspended.

On reaching there I found a large number of people standing around quietly and the officers shouting that no boats were to be lowered and that the vessel was not in danger of sinking. A few of the boats were partially filled with people, but I did not see any others getting into them.

Henry Needham, a British subject returning home with the intention of enlisting, like so many other of the young male passengers, could also testify to the general feeling that there was no immediate urgency to abandon ship. By this time, the ship was listing to starboard by some 15 degrees. The order not to launch any lifeboats had been followed, yet in many cases this meant trying to coax passengers out of boats which were already being filled. With each of the twenty-two lifeboats accommodating up to sixty-eight persons, this involved a good deal of organisation and persuasion.

As to people realising this danger, I think they did not, especially as I heard someone who came from the direction of the Captain’s bridge say, «The Captain says the boat will not sink». The remark was greeted with cheers and I noticed many people who had been endeavouring to get a place in the boats turn away in apparent contentment.

The worst situation was on the port side of the ship, where the list had caused all the suspended lifeboats to swing dangerously inboard. Unfortunately anxious passengers coupled with the general confusion led to the captain’s orders not being followed, and lifeboats 2 and 4 on this side of the ship were released. Both boats swung sharply and impacted on the side of Lusitania, crushing those passengers and crew who happened to be standing on the boat deck before sliding down the deck and smashing into the area immediately under the bridge. This tragic and wholly unnecessary incident killed and maimed many passengers and crew, including most likely a good number of women and children who would have been waiting patiently for a place in the boats.

Further chaos ensued on both sides of the ship, as the officers tried desperately to stop passengers getting into lifeboats or attempting to launch them themselves. Despite the crew’s best efforts, they were overwhelmed by desperate and angry people anxious to escape the sinking ship and lifeboats 6, 8 and 10 on the port side all suffered the same fate as the earlier ones, smashing against the side of Lusitania before sliding down the deck to add to the splintered debris and loss of life.

Passenger James Baker recalled the confusion over launching the boats on the port side of the ship, and the unclear instructions being received from the bridge.

The boat opposite the main entrance was being lowered, an officer in her. I noticed one man at the bow fall, paying out in jerks when a bigger jerk started a run, this he could not stop. I ran to the side and saw the boat’s bows in the water, her stern high in the air, not a soul in the boat, the officer holding on to the bow trying to get in. The stern stem had been wrenched away from the planks on both sides.

I went to the boat opposite the reading room and saw one of the crew clearing the couplings. While at work, two men (3rd class) got in. The main in charge (without uniform or cap) attacked them with a hatchet; they got out and we then filled the boat with women and children and, the word being given, a number of passengers pushed her out to clear the side. Owing to the list this was done by swinging her. Just as we had got her moving came a sharp order from the Staff Captain on the bridge – «Stop lowering the boats, there is no danger, clear out the boats». This order was obeyed. I helped out a number of ladies and advised those who had not got belts to get them at once.

By this time I noticed that though very much down by the bows, the list was hardly noticeable and I wondered why we were not allowed to lower the boats; we could have done so. A few minutes must have passed, when without orders the boat was again filled and we swung her clear and she was lowered to the level of the deck and then to B deck. But as she went down, her clinker sides caught bolt heads and projections and not having enough men to keep her off, she must have got damaged. Then again she started running and scraping down the side and just crumpled up like a match box; the men at both falls not having been able to hold her. A third boat on the port side had the same fate, crumpling up because there were not men enough in the boat to ward her off and because she went down too fast. In my opinion this was due to lack of supervision and the incompetence of the men at the falls. In one of these boats was Ambrose Cross.

A steward or someone told me to jump in and I did. There was no crush on deck at all. Then the boat wouldn’t move. Someone asked where the hatchet was, and no one knew. Then there was a slight rush from within and I remember helping in a lady in a violet costume. Then a big man with a lifebelt on precipitated himself on to me with great force, and that tore it. Down went the boat, but we had such a big list to starboard by that time that she struck against the ship and I think she must have smashed, for, after spending a brief time under water and being kicked and buffeted by fellow victims, I came up among what looked like the remnants of a boat. Although I am a strong swimmer, I thought to husband my strength and as the mast of the boat (I believe) fell to my share I took it and was drifted to stern (there was still a slight way on the ship) for a quarter of a mile, or possibly more, as distances at sea are deceptive.

Realising that no lifeboats were likely to be launched properly from the port side of the ship, James Baker looked elsewhere for a way to escape.

I then thought of the collapsible boats. No preparation was being made to clear them. With a penknife I released one opposite the smoking room, cut the lacing to the canvas covering and started on a second. [I] had cut away one of the straps and part of the lacing when I saw the water pouring over the bulwark under the Captain’s Bridge. I realised that the ship was pitching forward, so ran to the end of the deck, got over the side and slipped down to the «B» deck, then to the «C» deck; as I steadied myself the water ran over my boots and when it had got to my knees I sprang away and swam as hard as I could.

With the list now amounting to 20 degrees or more, those on board became more desperate. In one particularly unfortunate incident, an American first-class passenger, Isaac Lehmann, pulled a revolver out and threatened the crew stationed at lifeboat 18, ordering them to launch the boat full of passengers. Once released, the lifeboat smashed into the side of the ship’s hull and suffered the same disastrous fate as the other port-side boats. Wesley Frost, the American Consul at Queenstown and a later commentator on the Lusitania sinking, felt that the confusion, chaos and disorder evident were forgivable under the circumstances.

Unskilled persons in attempting to handle the falls or pulleys which lowered the lifeboats made awful failures; and several boats were released at one end only, spilling their occupants out into the sea. Other boats were never freed from the davits at all, and were therefore dragged down with their occupants when the ship sank. Still other boats were broken by lurching inboard or against the side of the vessel. For example, the second port boat swung in against the deck-wall of the smoking-room, and crushed to death or hopelessly crippled some thirty or forty passengers who were huddled together waiting for its preparation. In none of these accidents can strong blame be imputed to the persons on board the Lusitania. Probably instances did occur in which better judgement might have saved lives; but on the whole the standard of conduct not only as to courage but as to self-possession and resourcefulness was amazingly high.

By now the list had increased to a dramatic 25 degrees, yet the crew were experiencing some small success in launching lifeboats on the starboard side of the ship. Wallace Phillips was fortunate in this regard.

I saw several boats filled with people being lowered, and then walked along the extreme end of «A» deck. By this time the boat had taken such a decided list that I thought she was going over every second, so I climbed over the side and dropped into the lifeboat which had been lowered below me, this being one of the very few lifeboats that were properly launched from the ship, and it was in charge of First Officer Jones. I landed on the gunwale of the boat, but for an instant I was undecided whether to stay on or dive overboard, as the ship was coming on top of us. I should judge that our boat had the most advantageous position of the three or four others that were launched at the same time, and I rather imagine as the ship went down it must have crushed under it several of the boats.

After this there appeared to be another explosion in the engine room, as the most terrific quantity of water and soot shot out from one of the funnels, the funnels at this time being just submerged, and hit the people in our boat directly in the face at the same time blowing one woman out of the funnel who had been sucked in an instant before.

Some boats were lowered too quickly and smashed to pieces when hitting the water, while others were lowered unequally, resulting in their passengers being tipped out into the sea below. In the anxious haste and general confusion, many disastrous mistakes were made, as Archie Donald attested.

With my life belt in my hand I crossed over into the first class portion and went down on the lowest side and helped to load the second boat from the end. The stokers tried to get into it, and I can vouch that the crew were stationed at this boat in a proper manner. Some first class passengers and myself kept the men back and shouted that the women should be put in first. We eventually loaded all the women in sight to the number of about twenty, and when the boat started to be lowered the men were the only ones standing on the side. They began to lower away but unfortunately the forward fall began to run out too quickly while the rear fall seemed to stick in the block, the result being that the boat was hanging perpendicularly, all the passengers being thrown into the sea. They cut the hanging rope and the boat went into the water, but of course was water logged. The passengers seemed to be crawling up on a rope netting on the lower deck, climbing higher as the water reached them.

Nurse Alice Lines, carrying the three-month-old baby Audrey in her arms and with the five-year-old Stuart clinging tightly to her, had made her way up the stairway to the outside deck: «Just as I got outside on the stairway, there were men, the husbands of the wives I take it, who were throwing money and things of importance to their wives, into the lifeboats».

We eventually managed to get to the top to the lifeboat deck and I was on the port side. To get to the boat it was a climb, the ship was going, the people were falling in on the opposite side and a sailor came and grabbed Stuart and I followed. And he threw Stuart over the rail to a lifeboat and the lifeboat was just ready to go, it was full. Now I went to jump into the lifeboat and the sailor grabbed me back and he said, «It’s full, there’s plenty of room in the next one». I’m afraid I did get a bit hysterical, I yelled and to be quite honest I bit his hand and he let go and I jumped, thinking I was only going to jump quite naturally into the lifeboat but I jumped just as the lifeboat was going down and I went off to the side of it. The lifeboat landed in the water almost as I did and a man who was in the lifeboat leaned forward and grabbed me by the hair and I toppled over into the lifeboat. So I always say that my hair saved my life. And the baby was very tightly tucked up round my neck.

Alice’s dramatic jump into the lifeboat may well have been an elaboration, since she clearly suffered from memory loss after the traumatic sinking and some of her testimony contradicts known events. Yet her escape from the ship is included here for completeness.

In those final moments on board Lusitania, each passenger took what opportunities they could in order to escape the liner and so survive. Jane Lewis, accompanied by her husband and daughter, had made her way to one of the lower decks.

We were standing by a lifeboat on the ship, waiting to see what it could do. There was nobody about where we were hardly. But there was plenty in the water. And then my husband said he’d better go down to the cabin and get lifebelts. I said, «No, you’re not going down … if you go down there you’ll never get up again. If we’re going, we’re all going together». Well we stayed there and then there was a lifeboat, one small boat, in the water. It was tied or fastened to something. Then we got into the boat but you couldn’t get away and not any of the men could find a penknife on them. They seemed to have lost them all. So we got away eventually at last … I was thrown into the boat because we had to be quick.

There was a poor bandsman trying to get out of some of his uniform I think. He was on the deck with us and he couldn’t get out. And, oh, he was so fat. And then nobody could help him. There was nobody there to do anything for him. I don’t know what became of him, and why he got on the deck with that on I don’t know.

May Bird escaped, despite the starboard list still confounding the launch of the boats.

Of course there wasn’t enough lifeboats for everybody because we could only use one side. People were jumping overboard, getting a hold of deck chairs, floats, and that kind of thing. Some of them were jumping over, they didn’t wait for the boats to be lowered. Well the boat I got into was the last boat and I was the last person on deck to get into one.

Only the fact that the officer in charge recognised her as one of the ship’s stewardesses enabled her to escape.

When he saw who it was he said, «Well can you jump?» And it was rather a long jump, and I said I’d try. And I jumped into the middle of the lifeboat. The lifeboat had gone down past the davits and of course it was a very long jump. I should say about 15 feet. But I managed it. The officer was the only other member of the crew in the lifeboat. So he found rowing very difficult and asked, «Is there anybody here that can row?» Well I was the only other person who could row, so I took an oar. Of course I was very fond of rowing, I used to row a lot. I lived near a lake and I used to go and row quite a lot in my young days. So I was able to take an oar and very pleased to do it.

By this time the ship was listing very badly and almost leaning on top of us, so we had to row very, very quickly away. But not before we were showered with soot from the ship’s funnels, it came all over us. But we managed to get away safely. Of course it was a very sad sight to see hundreds and hundreds of people in the water, screaming for help, hanging on to deck chairs, hanging on to anything, begging to be taken into the boat when we dare not do it. Had we taken one more in we should have all been drowned. But it was a terrible sight, there were hundreds of them.

As one of the ship’s lookouts, Leslie Morton had been among the first to give warning of the impending disaster.

I went down the forward scuttle to see if my brother who was in the other watch down below had got out. I met him coming up, using seaman’s language about it, and then I went straight to my boat station on the top deck which was number 11 boat on the starboard side. The ship was heeling over about 35 degrees to starboard by this time and with the in-rush of water, which made all the boats on the port side useless, if our own station didn’t get away. There I met my brother, he was at that boat at one end, he had one end of it and I took the other, we got her full of people by lowering it down to deck level as the ship heeled over and lowered it into the water. The ship was heeling over all the time and with the boat full we tried to push off from the ship’s side but many of the passengers hung on to the ship – they didn’t feel that the big ship should be let go from this little boat they were in – and as the Lucy came further over […] the davit hooked on the near side gunwale of the boat and started to tip it inboard with all the people in it. And I yelled out to my brother, «Where are you going?» He went over the side at one end, I went at the other. I was a little worried because I knew he couldn’t swim, until I hit the water and came to the top. I took an instinctive look over my shoulder and he was doing a marvellous double trudgen stroke for France, apparently, 130 miles away, getting along beautifully.

Then, remembering a collapsible boat that had slipped off the deck a few minutes before, I should say the whole thing was over in 15 minutes, it takes longer to tell, I remember this collapsible boat slipping off the deck and I went back over the course as the Lucy passed me. She was under way all the time, the engines were going all the time, they couldn’t cut them off due to torpedo damage. I found this collapsible boat and ultimately got the sides up and in due course picking up people, everybody helping, we got it full of people. Passenger Archie Donald had delayed his escape until the very last moment.

A fireman by my side took a most beautiful dive from the rail, and I saw him swim in the water to the stern of the ship – it was then that I realised the danger and that the best policy was to leave the ship if possible. I then found an empty beer box which had two handles, and it entered my head that this would help to act as a life preserver. Taking my two watches I put them in my left hand trouser pocket and stripped my coat off, and with my beer box started to climb the stair to the next deck when I was met by a Doctor McCready of Dublin, whom I knew slightly. He wore a life belt and had one in his hand, and I said where did you get the life belts, and he said down in the cabins. I had never thought of life belts until this time, and luckily I discovered that I was on the port side of the same deck on which my cabin was situated, and there was a door which had been shut during the voyage, open. Going through here I found myself in the passage and was soon in my cabin. The deck had listed so much that it was hard to walk. I felt in the locker on one side of my cabin and found the belts gone, and felt on the other side and they seemed to be gone also, but by good chance I tried again at the very back and found the last remaining life belt.

I came out on the surface again, and went up on to the top boat deck. There I saw Mr and Mrs Stroud who had been through the Mexican War; he seemed to know exactly what to do – he had torn the clothing off his wife, and all she had on was her stockings and her life belt; he himself was tearing the cover off a collapsible boat. After helping him to accomplish this I stood and watched the people going into the lifeboat which was hung at that point, but I do not believe they ever managed to float that one, as the ship had listed so much that the boat could not clear the side.

I stood for a moment and immediately considered what was the best thing to do, and I remember wondering why I was not frightened; my brain seemed to be perfectly clear, and the thoughts seemed to crystallise at once […] Looking along the side of the ship with all the boats swung out, I saw the ship was going very quickly down, and that the boat deck rail and the water were rushing as it were towards me. Then I thought that it was time for me to leave the ship so getting a steward to tie on my life belt I put my money, which consisted of about £8 in my sock. I started to take off my shoes but found that there was no time. Jumping down about twelve feet in the water I of course went underneath, but with the buoyancy of the life belt soon came to the surface.

Swimming was the most marvellous revelation to me, the speed with which I seemed to get over the top of the water, my chest and head being high above the water, my legs acting as a good propeller, and swimming seemed to be an easy matter. As I looked behind me I saw the ship – the propellers and rudder were completely in mid air, and then with an explosion and the rattling of all the loose material leaving her deck she began to take the last plunge. Going over sideways I had great fear the mast was going to hit me, and my brain wondered whether the stay ropes were made of hemp and rope or wire – a most absurd thing to think of but details seemed to flash on one’s mind in these times – it missed me by 15 feet. Then a tidal wave, perhaps 3 feet high, picked me up and shot me out into the calm water. The suction or vortex drew me down. I came to the surface and opposite me there shot up an 8 × 8′ post and also a 2 × 6′ plank; if they had hit me they would most probably have killed me or broken a limb. However, I seemed to be guarded, and they missed me by a few feet.

Ambrose Cross was also treading water, but had managed to hold on to some debris from the ship along with other struggling passengers.

I found myself in company with a bald headed Jew, an elderly Jewish lady, a Belgian and some other woman. We also had one oar. The Jew groaned and called upon Moses alternately. He had a lifebelt and I told him to pull himself together, but it was no good, just a case of Kismet with him. The old lady was an awful sport; spat the salt water out of her mouth like a good ’un. I bucked her up, telling her she was doing splendidly, and I wished I could have helped to save her. None of these four could swim, so, of course, the mast or whatever it was, was well submerged, as they sprawled all over it instead of hanging on and treading water. For myself, I think I must have been lightheaded or something, for I felt that I didn’t care and generally took charge of my crew and passed the time of day with those on adjacent flotsam or jetsam.

Suddenly, Lusitania’s forward movement ceased.

The ship had seemed to stop her listing and to be stationary, and I thought perhaps we might get back, so told such of my lot as were capable to hold on and kick out, but it wasn’t for long. Suddenly she started again and I really think she must have completed her sinking in a matter of seconds. It was an awful sight and yet it fascinated you, the grace with which the huge thing slithered in, raising its stern on high at the last. So far as I remember, we heard no noises from where we were. Then came the worst part. We were alone. The space a few moments ago occupied by our luxurious home was a ghastly blank of almost still water. The swells caused by the sinkage rolled towards us, and with them came the dead bodies.

Remarkably quickly, the ship was lost beneath the waves, its funnels being the last part to sink out of sight. Treading water, James Baker recalled seeing the ship go down.

After a few strokes I looked over my shoulder, the place where I got over was under water, and from the beginning of the second class deck her stern was up in the air at an angle of about 40 degrees. I could see her keel, rudder and propellers. I swam hard for another few strokes, looked again and she was gone. I next saw washed past me foam and wreckage and, fearing to be hit, I turned to face it; light wreckage flew past me, being driven away from the ship. At the same time what appeared to be about the middle of the white foam rose a huge mound of water, I should say 12 to 15 feet high and 30 to 40 feet long. After a few seconds it subsided.

Jane Lewis had managed to escape in a lifeboat with her husband and young daughter.

The boat was going down. She went down, down, oh down. And I was in the little ship, the little boat on the water. My husband said to me, he said «Look round now, she’s going down now». And I said, «No, I won’t». I didn’t want to see it go down, and neither the children. But I thought I’d better look and I looked, just before – she was just going down, down into the water. The end of it like that was the last I saw of it. It was a ship that we’d had such a nice time on. People had all been happy there. They’re all gone.

The noise and chaos as Lusitania sank was followed by a startling calmness. After the ship had disappeared beneath the waves and the final disturbances of water had subsided, the contrast must have seemed to many as if the last twenty minutes had been but a horrible nightmare. ‘The sea was calm. And all you could see was bodies and wreckage of all furniture and everything that had been in the ship and was floating on the water.

Alice Lines lay in a lifeboat, safe with her two charges, and reflected on the final end of the mighty Cunard vessel. The sea was full of struggling people.

Oh yes, there were quite a lot of them swimming. There was quite a lot of them hanging on to deckchairs and tables and things that were floating. But the horror to me as far as the memories go was to see that beautiful boat, a huge ship supposed to be the largest in the world, disappear under my very eyes and all I could see all over was bodies and wreckage floating. That’s my last memory.

Throughout all of the chaos following the initial torpedo strike, during the many attempts to launch the lifeboats, and while individual passengers and crew attempted desperately to save their lives as Lusitania foundered, U-20 remained submerged close by. Captain Schwieger had a perfect view of events on board the ship as they happened and recorded as much in his log-book entry.

It does not take long for a great confusion to set in on board; the lifeboats are released and a part of them are set down on the water. While engaged on this the sailors must have lost their heads, in several instances the tackle is not uniformly secured and the lifeboats are hurled into the water with their bows or sterns first and sink instantly. Owing to the ship’s list which has got stronger they only succeed in releasing a few boats on the port side. The air pressure causes the decks to splinter. I notice at the bows the name Lusitania in gold letters. The funnels were painted black. No flag hoisted astern. The ship had been sailing at a speed of 20 knots.

14.25 hrs: As it seems to me that the ship no longer has much more time afloat I submerge to 24 m and cast off to the open sea. In any case I could not have launched a second torpedo into the midst of this crowd of humans trying to save themselves.

Once Lusitania had slipped beneath the waves, only seven of her lifeboats were afloat out of a total of twenty-two. Six had been successfully launched from the starboard side, while Number 2 boat had been swept off the ship when she sank. Although Number 14 boat had also been launched, the only one from the port side, it soon became filled with water and proved unusable. Also adrift among the wreckage were a good number of collapsible boats out of the forty-eight in total carried by Lusitania, many of which had also been swept out to sea once the ship sank. Wesley Frost believed that: «The collapsible lifeboats had for the most part been unfastened from their places by the ship’s seamen during the brief moments before the sinking; and this type of boat must have accounted for at least one- third of all the life-saving».

Lusitania finally sank beneath the waves at 2.28 p.m. From the moment that the torpedo hit her, the ship had stayed afloat for only eighteen minutes, and it would be this fact more than anything else which led to the enormous loss of life. Out of a total number of 1 960 passengers and crew, only 763 would survive.

Investigations

News of the sinking travelled fast and as soon as the Prichard family learned of the disaster, their first thought was of Preston. Had he survived? Was he injured? The lack of any immediate news from Preston himself would have been their major concern, and Mostyn therefore departed immediately for Queenstown, where any investigations into Preston’s whereabouts could be best undertaken. While he was away, his mother and sisters remained at the family home on Brockenhurst Road in Ramsgate, desperately scanning each daily newspaper for the latest lists of survivors and eagerly reading the eyewitness stories reported for any slight reference to their «Prets». The tall terraced house provided a fine view down the gently sloping street which ended on Victoria Parade, and one can easily imagine Margaret Prichard gazing across the cold sea of the English Channel in despair, wondering what had happened to her eldest son. One of his last letters home, with reference to his imminent medical exams, had closed with the postscript «Will write later, no news is good news». This phrase likely returned to haunt his family as they waited, hoping for the best but fearing the worst.

Mostyn arrived at Queenstown on Monday 10 May, accompanied by a family friend, Mr Heald. Both men established themselves at the Westbourne Hotel where, at 7.30 that evening, Mostyn first wrote home to his mother and sisters. Commanding a view across the harbour and being adjacent to the post and telegraph offices, the hotel proved to be a perfect base for the men to undertake their investigations.

My Dearest Gwen and all, Darling Mother and Gwladys, You may be sure I am trying to do my utmost. Mr Heald is so good – I don’t know what I should do without him. We arrived here at noon today and have spent half our time in [the] Cunard office and post office and have been to Military Hospital and wired to all the others, but no such person as dear Preston is in same.

The place is alive with miserable creatures like ourselves. The sights and one’s whole aim tends to the same question. Mr Heald and I were unable to see the bodies of those not identified but we saw the personal effects of them and nothing whatsoever lead to Preston’s identification. They were chiefly women and children and a few men whose ages were much above and below Preston’s … we saw their personal effects and nothing whatever helped with Preston.

Mr Heald has to leave tomorrow at 3 o’clock because of Ascension Day. But you need not worry about me, I am quite alright and you will be pleased to hear I asked someone about Preston and as soon as I showed [his] photo the man immediately knew him. He had two others (ladies) with him. He said Preston was perfectly well as far as he knew all the time, and once when he went on deck they asked him to play Quoits but he refused to do so. The women also recognised him. One woman said she lived at Montreal and when she went on board she soon recognised Preston. You need not worry about me for I have them and other very kind friends. Everyone is in the same plight and the universal sympathy of the entire town in simply amazing and splendid. Everyone speaks to everyone.