There are a few notable stories about premonitions related to the Titanic disaster. One of the most famous involves a man named Morgan Robertson. He wrote a novella titled «Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan», published in 1898, which featured a fictional ship called the Titan that hits an iceberg and sinks in a manner very similar to what happened with the Titanic. Robertson’s story had numerous similarities to the Titanic disaster, including the size and luxury of the ship, the iceberg collision, and the insufficient number of lifeboats.

Another notable premonition story involves passengers and crew members of the Titanic who reportedly had premonitions or unsettling dreams about the ship’s impending disaster. For example, some passengers had eerie dreams or feelings of dread before the voyage. While these accounts are intriguing, they are often seen through the lens of coincidence or psychological phenomena rather than actual supernatural foresight. The Titanic Building and the Age of the LinerTitanic disaster has generated a lot of myth and speculation over the years, contributing to the fascination with these premonitions.

Perhaps the eeriest aspect of the Titanic disaster was the large number of prophetic tales and premonitions that seemed to foretell its terrible fate. As early as 1886, the famed British journalist W. T. Stead wrote a fictional story entitled «How the Mail Steamer Went Down in Mid-Atlantic» for his newspaper, The Pall Mall Gazette. In the story, a liner sank after colliding with another ship, and most of the people aboard died because of a shortage of lifeboats. At the end of the piece, Stead added: «This is exactly what might take place and will take place if liners are set free short of boats.» Six years later, in Review of Reviews, Stead revisited the theme in another short work of fiction, «From the Old World to the New», in which a clairvoyant aboard White Star’s Majestic helped to guide a rescue of those aboard another ship that had struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic. Uncannily, the name Stead gave to the captain of Majestic was E. J. Smith – the same name as the captain of Titanic. Even stranger, Stead lost his life as a first-class passenger on Titanic.

In 1898, 14 years before the tragedy, the former merchant navy officer Morgan Robertson published the novella The Wreck of the Titan; or, Futility, in which an «unsinkable» British liner named Titan, on a voyage from New York to England, sank with 2 000 people aboard after being tipped on her side in a collision with an iceberg. Not only was the description of Titan unnervingly similar to Titanic – having roughly the same length, displacement, speed, watertight compartments and number of propellers – but the fictional ship also lacked anywhere near the proper number of lifeboats.

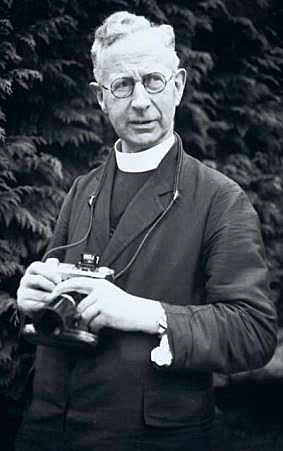

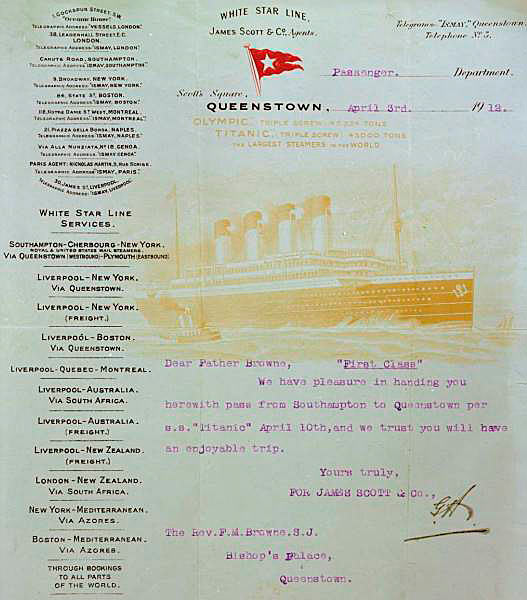

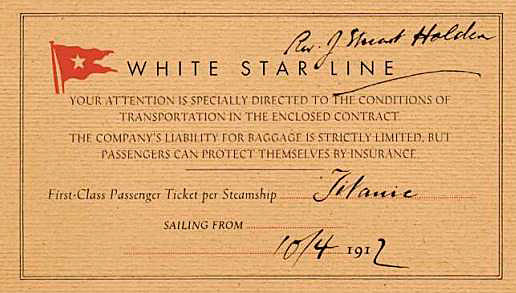

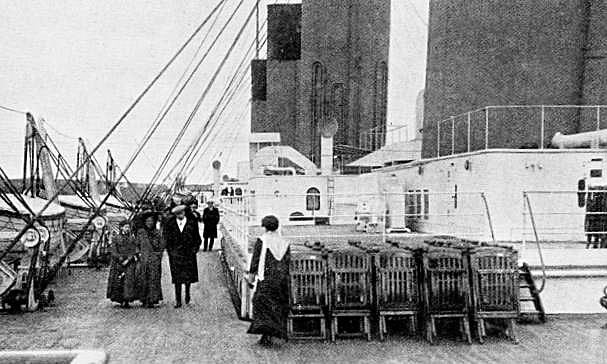

Equally as bizarre were the numerous portentous events surrounding people sailing on Titanic. One of the most fortunate of those to embark was Father Frank Browne, a theology student in Dublin. On 4 April 1912, he received an unexpected present from his uncle, the Bishop of Cloyne: a first-class ticket for the initial two stops on Titanic’s maiden voyage, from Southampton to Cherbourg to Queenstown, Ireland. While aboard, Browne was befriended by a wealthy American, who offered to pay his passage to New York. When Browne asked his Jesuit superiors for permission, he received the no-nonsense reply: «Get off that ship.» Browne followed his concerned supervisor’s instruction, and within just a few days found that the numerous photographs he had taken aboard Titanic became famous as the last ones of the doomed ship.

No Pope Although many consider one story that originated during the building of Titanic to be a myth, it remains one of the most often-repeated tales. It is said that the number 3 909 04 was scrawled on the hull as an addition to its official hull number, 401. When this was seen one day as a mirror image, it was noted with horror that it read «NO POPE». Many of the workers in Belfast were Catholic, and it is rumoured that there was great anxiety and concern among them, which later turned to certainty that the ship was destined for disaster.

Others with apprehensive relatives or friends were not so fortunate. John Hume, the Scottish violinist who was one of Titanic’s eight-man orchestra, had been aboard Olympic during the collision with HMS Hawke. This had unnerved his mother terribly, and she begged her 28-year– old son not to sail on Titanic after a dream told her of terrible consequences. Such a decision could have made gaining future employment with White Star difficult, so Hume boarded with the other musicians at Southampton – and all of them lost their lives. Similarly, Broadway producer Henry B. Harris ignored the impassioned pleas of his business associate William Klein not to sail on Titanic, and he and his wife embarked in Southampton. Four days later, Mrs. Harris was able to enter a lifeboat, but her husband paid the ultimate price.

There were numerous other confirmed instances of foreboding about a tragedy, which were or were not heeded by those scheduled to board. The latest addition to the litany of premonitions was made public only as recently as March 2007, when it was revealed that Alfred Rowe, a Liverpudlian businessman who also owned a ranch in Texas, posted a letter to his wife from Queenstown. Citing the near-collision with New York during the departure from Southampton, he told her that Titanic was too large, that she was a «positive danger», and that, were he still able to change, he would rather be on Mauretania or Lusitania. Rowe died in the disaster.

JOHN PIERPONT MORGAN – SURVIVOR Perhaps the most mysterious cancellation for Titanic was made by none other than J. P. Morgan. At one point Morgan was scheduled to occupy the glamorous port promenade suite on B. Deck. However, he cancelled his reservation, claiming, according to some sources, that his business interests required him to remain in Europe. Others indicated that Morgan backed out owing to ill health. However, two days after the tragedy, a reporter found him in a French spa town in the company of his mistress.

Three Departures

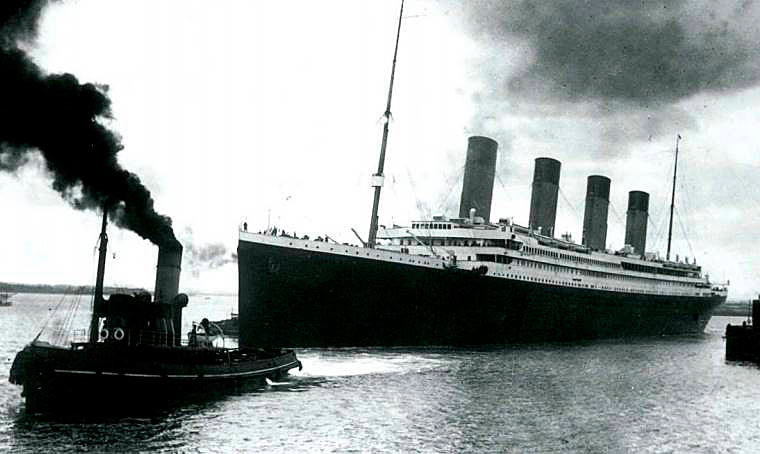

Wednesday, 10 April dawned fair and breezy. Throughout Southampton, hundreds of crew headed for Berth 44 at the dockyard, where at 6 am they were directed to their quarters aboard Titanic prior to general muster. Three and a half hours later, another massive influx occurred as most of the second- and third-class passengers arrived on the boat train from Waterloo Station, and were then guided to their separate entrances to the ship. At 11:30 am, scarcely half an hour before departure, another train arrived, this time holding first-class passengers, who were efficiently escorted to their staterooms. Promptly at noon, with hundreds of family members, well-wishers and spectators waving and cheering from the quayside, three loud blasts announced departure. The sound had hardly stopped reverberating through the air before disaster nearly struck.

Having been pulled out of the enclosed dock area by five tugs, Titanic began to move slowly – and then more rapidly – along the River Test. The turbulence caused by the forward motion of a ship with such incredible size and draft was dissipated harmlessly into the river on her starboard side. But on her port side, the displaced water was trapped between the monstrous ship and the dock’s bulkheads. Tied in tandem at Berth 38 were two liners, Oceanic and New York, that were out of service until they could be coaled.

As Titanic swept near them, the displaced water caused New York to bounce up and down with such violence that all six of her mooring lines snapped. And as Titanic continued, the waves in her wake drew the stern of the now-free New York in an arc towards her. George Bowyer, the pilot, immediately ordered «stop engines» and then «full astern», but a collision seemed inevitable. Fortunately, the alert Captain Gale of the tug Vulcan swung behind New York’s stern and got a wire rope on her port quarter to slow her drift. Danger was averted by no more than a metre or so, and those who had felt ill at ease about coming on the ship must have seen it as another harbinger of bad tidings.

Titanic was now forced to wait an hour while New York was taken out of harm’s way and additional lines were placed on Oceanic. She therefore did not arrive at her first port of call, Cherbourg, until 6:35 pm. Cherbourg’s piers were not large enough to accommodate Titanic, and the two purpose-built White Star tenders, Nomadic and Traffic, ferried arriving and departing passengers and cargo from ship to harbour. Twenty-two passengers disembarked, to be replaced by 274, each of whom had made the six-hour train ride from Paris aboard the Train Transatlantique. Among these were 47-year-old American mining magnate Benjamin Guggenheim; famed English dress designer Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon and her husband, Sir Cosmo; and Denver socialite Mrs. James Brown, known to her friends as «Molly».

The Crewmen who Missed the Ship Most of the crew of Titanic signed on during Saturday, 6 April. But when the ship sank, 24 of the original crew were not aboard. Of those, ten were listed as «failed to join», eight as deserted and the others as «left by consent», discharged, transferred or «left ship sick».

Among the fortunate were the Slade brothers from Southampton – Bertram, Tom and Alfred – each of whom had been signed on as a fireman. They temporarily left the ship for a pint of beer and missed catching it by moments after they were delayed by a slow train in their path.

An hour and a half later, Titanic departed for Queenstown, Ireland, where, at 11 am on 11 April, she anchored 3,2 kilometres (2 miles) offshore, as once again she was too vast to enter the harbour. White Star tenders took off eight passengers – including Frank Browne, whose photographs were the last of the ship – and ferried 120 passengers and 1 385 sacks of mail to the ship. Meanwhile, fireman John Coffee stowed away in the offgoing post and disappeared into his native Queenstown. Onboard, an unknown fireman disturbed passengers when his soot-covered face was seen coming out of the hindmost of the ship’s four funnels. It was the dummy funnel used as a ventilator rather than a chimney, as the prankster knew full well, but to some of the squeamish aboard, it was an evil omen.

All was now ready for the transatlantic voyage to New York, so at 1:30 pm the American flag was raised and those aboard watched the green of Ireland fade into the distance. For many of them, it was the last time they would ever see land.

«We had a very near collision with the American line boat New York which delayed us over an hour, & instead of arriving at Cherbourg at 5 o’c we did not get there till 7 o’c & consequently shall be late all through. I am told we shall probably get into New York, provided all goes well, late Tuesday night which means we shall land early Wednesday morning. It is lovely on the water, & except for the smell of new paint, everything is very comfortable on board.» – Marion Wright

Already some aboard were disturbed by what they considered evil omens

Thomas Hart: Dead or Alive? Among the crew officially lost on Titanic was a fireman whose discharge book named him as Thomas Hart of 51 College Street, Southampton. So one can imagine his mother’s shock when, a month later, her son showed up at the door. It turned out that he had never boarded the ship because the night before joining, he had lost his discharge book in a pub. He was then afraid to admit his story immediately after the disaster. No one has ever determined who signed on in Hart’s name – and died for his deception.

Ice Ahead

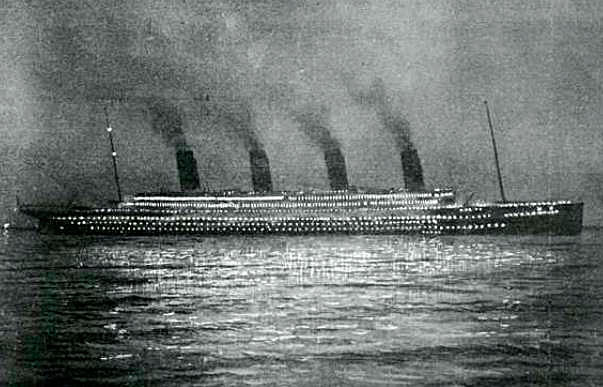

For three days after leaving Queenstown, Titanic raced across the Atlantic, accompanied by conditions most passengers loved – blue skies, light winds and calm seas. Yet that state of affairs belied the fact that almost all vessels in the North Atlantic shipping lanes were facing problems of a serious nature. In the far north, the winter had been the mildest in three decades, causing many more icebergs than normal to calve off the Greenland ice shelves. A little farther south, however, temperatures had been cold enough so that as the vast fields of ice drifted south, they did not melt as quickly as usual. The result, as shown by reports of ships during the week beginning 7 April, was that an immense band of ice, extending from 46° North to near 41° 30’ North and from about 46° 18’ to 40° 40’ West, was moving slowly southwest. Since Titanic was heading towards «the corner» – a point at 42° North, 47° West at which ships usually set a new course, depending on whether they were going to New York, Boston or other locations – she was aiming directly for this ice.

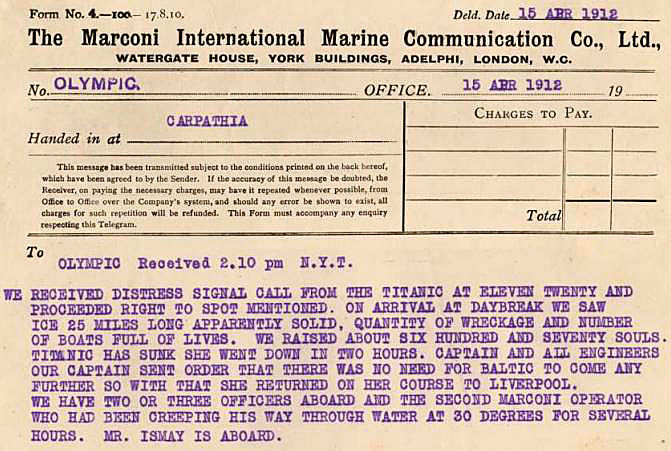

Sunday was normally a special day aboard ship, and the morning of 14 April was like most others, with Captain Smith conducting the Church of England service in the first-class dining saloon, the assistant purser leading another in the second-class saloon and Father Thomas Byles overseeing the Catholic Mass, first in the second-class lounge, then in the third-class areas. But in the wireless room, the domain of Marconi senior wireless operator Jack Phillips and junior operator Harold Bride, a series of messages began to come through that would soon take on unimagined significance.

In the preceding days, at least a dozen messages had arrived from other ships informing Titanic of icebergs ahead. At 9 am on the 14th, Phillips received another, from Cunard’s Caronia, reporting icebergs, «growlers» (smaller but still dangerous pieces of ice) and an extensive field of ice at 42° North, 49-51° West. Phillips immediately took it to Captain Smith, who had it posted on the bridge for his officers. Ice warnings continued to arrive, including some from the Dutch Noordam at 11:40 am and then, at 1:42 pm, from the Greek steamship Athinai via White Star’s Baltic, a message that, rather than post on the bridge, Smith strangely handed to Ismay, who put it in his pocket. Almost simultaneously, another report of ice – at 41° 27’ North, 50° 8’ West – was received by Phillips from the German ship Amerika, but the chief wireless man, according to Bride, failed to notify any officers.

Second Officer Charles Lightoller One of the key figures in the chaotic last hours of Titanic was 38-year-old Second Officer Charles Lightoller, who had also commanded the last four-hour watch (6-10 pm) prior to the collision. Lightoller had gone to sea at 13, joined White Star Line in 1900 and been promoted to first officer before being temporarily dropped back to second officer when Chief Officer Henry Wilde joined Titanic late. Throughout the evening, Lightoller expressed concerns about the falling temperature and urged his lookouts to keep their eyes peeled for icebergs despite a calm sea that made spotting them exceptionally difficult.

All told, seven ice warnings were received during the day. One, at 7:30 pm, came from the Leyland ship Californian, which reported three large icebergs a short distance north of Titanic’s route. Bride took it to the bridge, but the message did not reach the captain because he was in the à la carte restaurant at a dinner party given in his honour by the wealthy George and Eleanor Widener of Philadelphia. Yet another message, which confirmed heavy pack ice and icebergs, came at 9:40 pm from Mesaba, but because Bride was sleeping, Phillips was unable to leave his post to take it to the bridge. Meanwhile, the temperature outside began to drop, decreasing from 6,1 °C (43 °F) at 7 pm to 0,5 °C (33 °F) 2 hours later.

«I was on watch on the poop in the First Watch (8 PM till midnight) on the night of April 14, 1912. The night was pitch black, very calm and starry, around about 11 pm I noticed that the weather was becoming colder and [there were] very minute splinters of ice like myriads of coloured lights… [A]bout 11:40 pm I was struck by a curious movement of the ship it was similar to going alongside a dock wall rather heavy… as we passed by it I saw it was an iceberg.» – George J Rowe, quatermaster on board Titanic

The final ice warning – as it turned out, Titanic’s last chance – was sent out at 11 pm by Cyril Evans of Californian. But the message was not taken by Phillips, who was busy sending and receiving passengers’ messages via the Cape Race station in Newfoundland, a task normally carried out at night, when the wireless transmitting range trebled from 650 kilometres (400 miles) during the day to 1 950 kilometres (1 200 miles) at night. Thus, for a variety of reasons, only one of the messages had reached both the captain and the bridge in a timely fashion. In a time of desperate danger, the officers on watch were unaware of the extent of the peril into which they were steaming.

Californian on the Air As well as monitoring traffic for general messages and specific warnings, wireless officers sent and received messages for passengers. At 11 pm on 14 April, Jack Phillips was in contact with Cape Race station, when a message burst in from a nearby ship. «Say, old man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice», transmitted Cyril Evans from Californian. But before Evans could give his location, Phillips heatedly responded, «Shut up! Shut up! I am busy. I am working Cape Race.» Evans, hoping to pass on important information, monitored Titanic for 25 minutes, but since Phillips continued to transmit, he finally shut down and went to bed.

«[I]t was 11:25 pm, 14th April when there was a heavy thud and grinding tearing sound. The telegraph in each section signalled down Stop. We had a full head of steam and were doing about 23 knots per hour… We had orders to ‘box up’ all boilers and put on dampeners to stop steam rising and lifting safety valves. Well, the trimmer came back… and he said «Blimme we’ve struck an iceberg». We thought that a joke.» – George Kemish, assistant in No. 5 Boiler Room

«I was on deck in the afternoon of April 14 between 5-6 o’clock and Mr. Ismay came and… thrust a Marconigram at me, saying, we were among the icebergs. Something was said about speed and he said that the ship had not been going fast now that they were to start up extra boilers. The telegram also spoke of the Deutschland, a ship out of coal and asking for a tow and when I asked him what we were going to do about that he said they had no time for such matters, our ship wanted to do her best and something was said about getting in Tuesday night.» – Emily Borie Ryerson

The Collision

Despite the repeated warnings of ice throughout the day, by 11:30 pm on 14 April, Titanic was still racing along at nearly 22 knots. The ship was well supplied with specialist lookouts, and in such clear conditions, Captain Smith assumed any ice would be seen far ahead. However, not only was the night moonless, thereby eliminating the sheen off the surface of any ice, but the conditions were so calm, with no waves and no breeze, that normal wave action, which would form a lighter ring around the base of any icebergs, was absent.

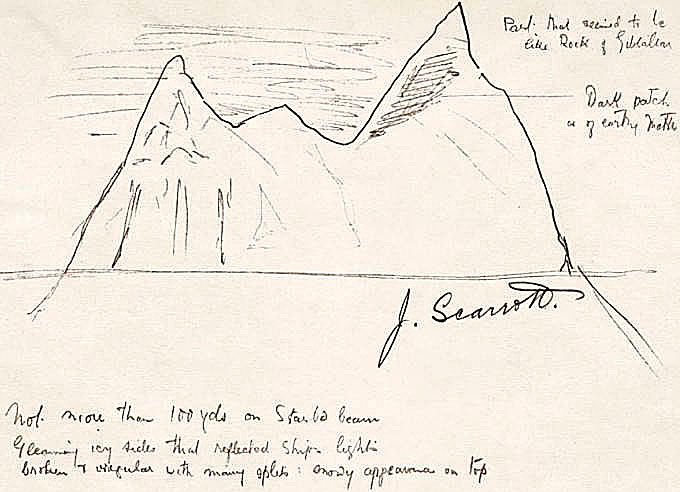

About 15 metres (50 feet) above the forecastle deck, lookouts Fred Fleet and Reginald Lee stared out of the crow’s nest into the darkness. At 11:30 pm they spied a misty haze on the horizon but could not make out anything definite, in part because the binoculars for the lookouts had disappeared before the ship reached Queenstown. They could only strain with the naked eye to see through the darkness.

Suddenly, at 11:40 pm, Fleet spotted a dark object dead ahead. He immediately rang the 41-centimetre (16-inch) brass bell that hung above him and picked up the phone to the bridge, which was answered by Sixth Officer James Moody. «Iceberg right ahead», Fleet stated. Within moments, First Officer William Murdoch ordered «Hard a-starboard» (dictating that the ship’s bow would swing to port), telegraphed the engine room «Stop. Full speed astern» and closed the ship’s watertight doors.

Titanic began to swing to port away from the iceberg – one point, then two – but it was not enough. The iceberg had been spotted at less than 450 metres (500 yards), and although the top of the ship did not collide with it, deep below the waterline some 90 metres (300 feet) of the hull scraped and bumped against the ice. The intense pressure caused the plates to buckle and the rivets to pop, opening a long, intermittent gash that penetrated the first five compartments, including the forward boiler room.

«When we were clean of the ship I said what’s the best thing to do Mr. Ismay he replied you’re in charge we could see nothing only this white light so I told them to pull away. Mr. Ismay on one oar Mr. Carter on another and the 4 of the crew one each and one I steered with 7 oars. We had been pulling for about 10 minutes when we heard a noise like an immense heap of gravel being tipped from a height then she disappeared. We pulled on but seemed to make no headway gradually dawn came and soon we could make out some boats and more ice.» – George R. Rowe

«Mr. Phillips now told me that apparently we had struck something, as previous to my turning out he had felt the ship tremble and stop, and expressed an opinion that we should have to return to Belfast. I took over the Telephone from him and he was preparing to retire when Captain Smith entered the cabin and told us to get assistance immediately. Mr. Phillips then resumed the phones, after asking the Captain if he should use the regulation distress call CQD. The Captain said «Yes» and Mr. Phillips started in with CQD, having obtained the Latitude and Longitude of the Titanic.» – Harold Bride

Within a minute, Captain Smith had raced to the bridge, and he quickly sent Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall to ascertain the extent of the damage. Most of the passengers were not aware of the severity of the impact, although some were intrigued that large fragments of ice had come cascading down on the forward well deck, while others claimed to have felt anything from a slight shock or trembling to a strong jar accompanied by a grinding noise.

North Atlantic Icebergs It is likely that the iceberg with which Titanic collided calved from a major glacier in West Greenland. Each year, some 10 000-15 000 large icebergs or smaller chunks of ice known as «growlers» float south to the region in which Titanic sank. Icebergs are composed of fresh water, with approximately seveneighths of their mass below the water line; mass does not refer to height out of the water, which can vary greatly in proportion. The iceberg that Titanic hit was estimated to be 15-30 metres (50-100 feet) high above the water and 60-120 metres (200-400 feet) long.

It was considerably worse than that in boiler room No. 6, where Second Engineer James Hesketh and Frederick Barrett, a leading stoker, heard a terrible rending sound and water suddenly exploded through a gash about 60 centimetres (2 feet) above the floor. They dived into the next room as the watertight door closed, only to find another tear in the steel plates and another jet of water shooting towards them. By the time they climbed to a higher deck, the water in No. 6 boiler room had already risen 2,4 metres (8 feet).

Within 15 minutes, Boxhall reported back to Captain Smith, who shortly thereafter received an even grimmer report from Thomas Andrews of Harland & Wolff. Andrews had quickly realized the gravity of the situation. Titanic could float with any two of her watertight compartments flooded; she could even remain afloat if it were the first four compartments that were breached. But five had been opened up, and the fifth – boiler room No. 6 – and those after it did not have watertight bulkheads that extended to the uppermost decks. When boiler room No. 6 finished flooding, the water still pouring in would reach E deck, and would then overflow into the sixth «watertight» compartment from above. As each successive compartment filled and the bow was pulled further under, the next compartment would again start to fill.

Thomas Andrews No one knew Titanic better than 39-year-old Thomas Andrews, managing director for Harland & Wolff in charge of design. Andrews joined the company at the age of 16 as an apprentice and eventually rose to a position of prominence. He boarded Titanic in Belfast to determine if any adjustments were needed, and to oversee the company’s «Guarantee Group» that would effect the changes. After advising Captain Smith that the ship was doomed, he encouraged passengers to make their way to the lifeboats. He was last seen in the first-class smoking room, staring into space with his life-jacket in front of him.

Andrews informed Smith that the «unsinkable» ship was going to do just that. No one knew better than Andrews that they were far short of the necessary lifeboats, meaning many of the passengers, like Titanic herself, had only an hour or two to live.

«I was a bride of 50 days. My husband and I were on our way to America to make it our home. He had been to America before where he had a business. When I first realized that something was wrong, it was 11 o’clock at night and I was fast asleep. Suddenly I heard a tremendous noise and immediately I knew the ship had been hit hard. It almost threw me off the bed. The motor stopped at once. My husband and I jumped up and ran to see what had happened. We went to the engine room and saw the crew trying to repair parts of the ship. We were still wearing our nightclothes.» – Celiney Decker

Man the Lifeboats

As soon as it became obvious that Titanic was mortally wounded, Captain Smith ordered the crew to be mustered, the lifeboats to be uncovered and the passengers brought up to the decks. He then directed Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall to calculate the ship’s position. His estimate – 41° 46’ North, 50° 14’ West, which was off by many miles – was taken to Jack Phillips in the wireless room, who began sending out distress calls.

The inefficiency and confusion brought about by sailing on what was perceived as an «unsinkable» ship quickly became apparent. There was not a consistent plan of action, most of the crew had not received adequate training in launching the lifeboats and the captain had not held the standard passenger lifeboat drill. Moreover, most of the passengers were already in their cabins, there was no public address system and when the stewards informed the passengers of the situation, they gave widely varying instructions. Slowly, however, a number of people made their way to the promenades and boat decks.

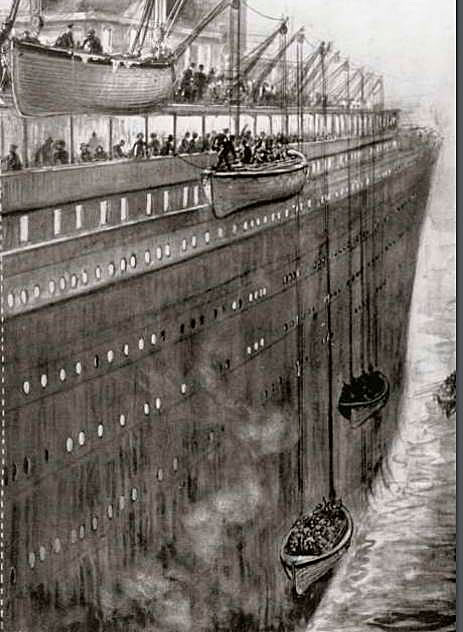

At 12:25 am, Smith ordered the loading of lifeboats, with women and children first. Even this was carried out haphazardly as, on port side, men were denied access to the boats, while on starboard they were allowed in if there were no women waiting. The actual loading of the boats began to bring home the reality of the dangers, and many passengers crowded the pursers’ offices to demand their valuables back.

Several other problems became apparent as the boats were loaded. First, many of the passengers were extremely hesitant and, after looking at the water far below, chose to not leave the comforts of the ship for the tiny, creaking vessels. In addition, the officers were concerned about loading the boats too heavily, evidently unaware that the new Welin davits were able to withstand the full load of 65 adults. One plan was to lower the boats half-full, and then take more passengers from the gangway doors at water level, but the men sent to open the doors disappeared. Boat after boat went down the side with numerous empty spaces on it.

CQD: THE WIRELESS EFFORTS At 12:15 am, Jack Phillips started tapping out the emergency signal «CQD» (often said to stand for «Come Quick, Danger»), followed by Titanic’s call letters – MGY – and her estimated position. Ten minutes later, Harold Cottam of Carpathia, 94 kilometres (58 miles) away, came onto the frequency to tell Phillips there were numerous messages from Cape Cod for Titanic. Receiving Phillips’ distress signal, the amazed Cottam responded, «Shall I tell my captain? Do you require assistance?» «Yes», Phillips replied. «Come quick.» Cottam raced to the bridge, Captain Arthur Rostron was awoken, and within minutes Carpathia was on her way.

At about 12:45 am, First Officer William Murdoch ordered the first lifeboat – Number 7 on the starboard side – to be lowered away with only 28 people aboard. Near the same time, Boxhall fired off the first of a series of distress rockets. Hope increased when the lights of another ship became visible some 10-16 kilometres (6-10 miles) off the port side.

«I had not heard the Band Playing, but in the distance I could hear people singing ‘For Those in Peril on the Sea’. After a while Mr. Webb got all the Lifeboats to keep together as he said there was a better chance to be seen. We transferred our 58 passengers to the other boats, and then started to search for any survivors after the ship had disappeared. Before she sank we could see her well down at the Fore port and her stern well out of the water. Some lights were still showing and continued to do so till she took the final plunge.» – A. Pugh

Lifeboat 5 was the second boat lowered, with some 40 occupants. In command of it was Third Officer Herbert Pittman, whom Murdoch sent so that he could also look after the other boats when they reached the water. Also in the boat was Quartermaster Alfred Olliver, who, as it descended, desperately tried to find the plug for the hole through which excess water drained when the boat was stored. Confronted by uncooperative passengers, he succeeded in finding and inserting the plug only after the boat had reached the sea and started taking water.

He survived, but suffering the stigma of having been a man in one of the lifeboats for the rest of his life

Meanwhile, on the port side, some 25 women were loaded into Lifeboat 6, with Quartermaster Robert Hichens and lookout Frederick Fleet, who had first seen the iceberg, as the only crew. Second Officer Charles Lightoller ordered Hichens to row the vessel to the ship in the distance and come back for more passengers. As the boat started to descend, Mrs Margaret «Molly» Brown of Denver – who had just persuaded several fearful women to get in and was going to help out elsewhere – was grabbed by two well-meaning acquaintances and dropped 1,2 metres (4 feet) over the side into the boat. She quickly realized there were not enough men to row to the distant light and demanded more. With Lightoller’s blessing, Major Arthur Peuchen, a Canadian yachtsman, swung out 1,8 metres (6 feet) onto the ropes and let himself down hand-over-hand.

DOG THE LIFEBOATS Just as every other whim of Titanic’s first-class passengers was catered to, dog owners were pleased by spotless kennels and crew detailed to walk the dogs daily. There were so many dogs aboard that a show had even been scheduled. Although honeymooning Helen Bishop had insisted her dog Frou Frou reside in her cabin, she left it behind because she acknowledged there was not enough room for all the people. Two dogs did survive, however. Margaret Hays took her Pomeranian into Lifeboat 7, and Henry Harper escaped in Lifeboat 3 with his Pekinese named Sun Yat Sen.

«All the boats were gone by now except No 9 and there was a bit of Trouble there the Chief officer was threatening someone and fired 2 revolver shots shouting now will you get back I was not near enough to see if anyone was shot after No 9 had left the Chief Officer shouted any crew here and about 7-8 stepped forward and he said hurry men up there and put that boat adrift it was a collapsible on Top of the Smokeroom we got it down to the deck but could not overhaul boats fall [sic] as they were hanging down shipside in water.» – Walter Hurst

«The Boat Deck was thronged with people. Many women and children had to be forcibly put in the Boats. They felt much more safe on the Decks of the Big Liner than in the small boats about 90 FT above the water line. Therefore the Boats that got away first did not take half the number of people they could have done, and then later when we realized things were really serious the boats getting away later were very much overloaded. The Band had stopped playing by now, about the last person I took particular notice of was W. T. Stead (novelist) calmly reading in the First Class Smoke room. – George Kemish».

As more boats reached the water below, the anxious people still aboard Titanic began to realize that many of them were not going to survive.