Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation Weakens: What It Means for Our Climate

A significant network of ocean currents known as the “great global ocean conveyor belt” is experiencing a slowdown, which poses a problem as this system is essential for redistributing heat globally, affecting temperatures and rainfall patterns.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is responsible for transporting heat northward through the Atlantic Ocean and plays a crucial role in regulating climate and marine ecosystems. Currently, it is weaker than it has been in the last 1 000 years, potentially due to global warming. Climate models have struggled to accurately reflect these changes until now.

Recent modeling indicates that the recent weakening of ocean circulation can be explained by considering the meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Canadian glaciers. The findings suggest that at a global warming level of 2°C, the Atlantic overturning circulation could be about one-third weaker than it was 70 years ago. This would lead to significant climate changes, including accelerated warming in the Southern Hemisphere, harsher winters in Europe, and weakened tropical monsoons in the Northern Hemisphere. Additionally, these changes may occur sooner than previously anticipated.

The Atlantic ocean circulation has been continuously monitored since 2004, but a longer-term perspective is necessary to understand potential changes and their causes. Sediment analysis techniques indicate that the Atlantic meridional circulation is currently at its weakest in a millennium, approximately 20 % weaker since the mid-20th century.

Evidence shows that the Earth has warmed by 1,5°C since the industrial revolution, with the Arctic warming nearly four times faster in recent decades. The melting of Arctic sea ice, glaciers, and the Greenland ice sheet is contributing to this issue. Since 2002, Greenland has lost 5 900 billion tonnes of ice, which is equivalent to an 8-meter thick layer of ice covering the entire state of New South Wales.

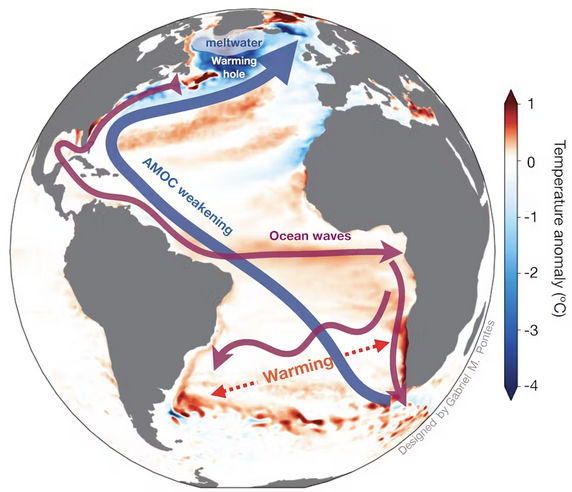

The influx of fresh meltwater into the subarctic ocean is less dense than salty seawater, preventing it from sinking and reducing the southward flow of cold, deep waters from the Atlantic. This also weakens the Gulf Stream, which is responsible for the milder winters in Britain compared to other regions at similar latitudes.

The new research highlights that meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Arctic glaciers is a crucial factor in understanding climate changes. When included in simulations, the slowing of oceanic circulation aligns with observed realities.

Source: nature.com

Furthermore, the study reveals that the North and South Atlantic oceans are more interconnected than previously believed. The recent weakening of the overturning circulation has masked the warming effects in the North Atlantic, creating a “warming hole.” As the oceanic circulation weakens, the surface waters south of Greenland have warmed less than other areas.

The research indicates that changes in the North Atlantic can impact the South Atlantic within two decades, providing new evidence for the slowdown of the Atlantic overturning circulation over the past century. The introduction of meltwater in the North Atlantic results in localized cooling in the subpolar region and warming in the South Atlantic.

Future climate projections suggest that the Atlantic overturning circulation could weaken by about 30 % by 2060, but this does not account for the meltwater entering the subarctic ocean. Continued melting of the Greenland ice sheet could raise global sea levels by approximately 10 cm over the next century. If this meltwater is factored into climate models, the circulation could weaken by 30% as early as 2040, 20 years sooner than previously estimated.

Such a rapid decline in the overturning circulation will disrupt climate and ecosystems, leading to harsher winters in Europe and drier conditions in the northern tropics, while the Southern Hemisphere may experience warmer and wetter summers. The climate has already changed significantly in the past 20 years, and accelerated ice sheet melting will further disrupt the climate system, emphasizing the urgent need for humanity to reduce emissions swiftly.