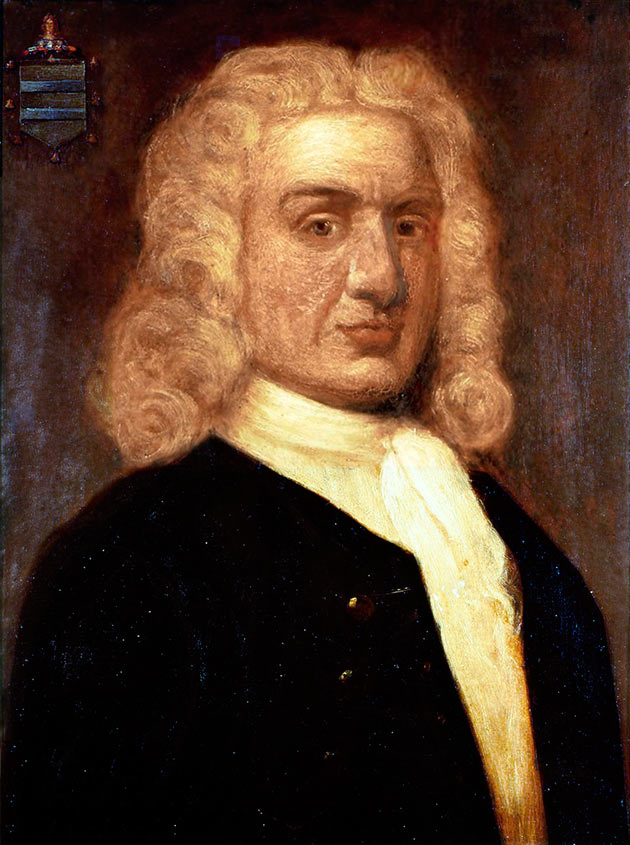

Pirate Captain Kidd, originally a Scottish sailor, began his career as a privateer, a mariner commissioned to target enemy ships on behalf of a government. In 1695, he was granted a privateering commission by the British government to fight pirates in the Indian Ocean. However, Kidd’s mission faltered when he struggled to find legitimate targets and faced discontent among his crew. Turning to piracy himself, he captured various ships, which led to his eventual downfall.

By 1699, Kidd returned to New York with a ship laden with loot, but his fortunes took a drastic turn when he was arrested and charged with piracy and murder. Despite his defense that he had been acting under legitimate orders, he was found guilty and executed in 1701. His trial was highly publicized, and his life story became a notable part of pirate lore, symbolizing the dangerous and unpredictable nature of maritime law and privateering in the late 17th century.

Chesapeake Bay lies on the eastern seaboard of North America and is a vast inland sea surrounded by innumerable creeks and estuaries. In November 1720 the ship Prince Eugene of Bristol entered the bay and headed for the entrance to the York River. Instead of proceeding a few miles upstream to Yorktown, she dropped anchor at the mouth of the river. That night the ship’s longboat was lowered over the side. Six bags filled with silver coins were stowed in the stern sheets of the longboat, and six heavy wooden chests were stowed amidships. The boat was rowed ashore in the darkness. The wooden chests were unloaded and carried up the beach and buried in the sand. When the longboat returned to the anchored ship, Captain Stratton gave the orders to get under way. The anchor was heaved up, the sails were set, and the Prince Eugene slowly made her way up the river, towing the longboat astern.

One of the members of the crew was Morgan Miles, a twenty-year-old Welshman from Swansea. When the ship reached Yorktown, he slipped ashore and informed the authorities that his captain had traded with a pirate in Madagascar. He told them that the Prince Eugene had sailed to the pirate harbor at Sainte Marie in the north of the island and met up with Captain Condell, the commander of the pirate ship Dragon. A boatload of brandy had been sent across to the pirates, followed by other goods from the merchant ship’s cargo. He had observed Stratton drinking with the pirate captain under a tree, and had seen a great quantity of Spanish silver dollars brought on board the Prince Eugene. The ship’s carpenter had been ordered to make some chests to hold the money.

Captain Stratton was arrested in Yorktown, interrogated, and imprisoned. A few weeks later he was sent back to England on board the British warship HMS Rye. Another member of the crew, Joseph Spollet from Devon, told the authorities that he understood that the value of the Spanish silver which Stratton had acquired from the pirates was £9 000 (the equivalent of more than £500 000). There is no record of what happened to the buried chests of silver. Presumably they were recovered by the authorities in Yorktown and confiscated.

Although buried treasure has been a favorite theme in the pirate stories of fiction, there are very few documented examples of real pirates burying their loot. Most pirates preferred to spend their plunder in an orgy of drinking, gambling, and whoring when they returned to port. The case of Captain Stratton described above is one of the rare instances of treasure being buried, and although the treasure in question was looted by pirates, Stratton himself was a dishonest sea captain rather than a pirate. Another case which is well documented took place 150 years earlier. Following his attack on the mule train at Nombre de Dios, Francis Drake and his men made their way to the coast and found that their ships had been forced to sail down the coast to avoid a Spanish flotilla. Drake ordered his men to bury their huge haul of gold and silver, and while some of his crew stayed behind to guard the buried hoard, Drake and the others set off in a makeshift raft to contact his ships. After six hours’ sailing they sighted the ships and were picked up. That night they returned to the spot where the treasure had been buried, retrieved it, and set sail for England. While Drake’s raid at Nombre de Dios made his name and his fortune, the incident of the buried treasure never attracted much attention.

Source: wikipedia.оrg

The pirate who seems to have been largely responsible for the legends of buried treasure was Captain Kidd. The story got around that Kidd had buried gold and silver from the plundered ship Quedah Merchant on Gardiners Island near New York before he was arrested. Because of the extraordinary attention given to Kidd’s exploits in the Indian Ocean and his subsequent trial and execution, he became one of the most famous pirates of history and the matter of the buried treasure received more attention than it ever deserved. The irony of it all is that Kidd never intended Review of Pirate Tactics in Ship Combatto become a pirate and to the end maintained his innocence of all wrongdoing. It was his misfortune to became a pawn in a political game involving players in London, New York, and India.

Kidd was a victim of circumstance, but he was also the victim of defects in his character. He seems to have had some of the same traits as Captain Bligh of the Bounty. He was a good seaman, but he had a violent temper and a fatal inability to earn the respect of his crew. Unlike Bligh, who was a small man, Kidd was large and powerful and bullied his men. He was constantly engaged in arguments and quarrels. A local agent who met him at the Indian port of Carwar described him as a «very lusty man, fighting with his men on any occasion, often calling for his pistols and threatening any one that durst speak anything contrary to his mind to knock out their brains, causing them to dread him…» He annoyed dockworkers and sea captains by his arrogant manner and his habit of boasting about his grand connections. He deluded himself about his motives and his actions when he turned pirate in the Indian Ocean, and no doubt deserved the biting comment which was made by a Member of Parliament at the time of his trial: «I thought him only a knave. I now know him to be a fool as well».

William Kidd was born about 1645 at Greenock, the Scottish port on the Firth of Clyde. His father was a Presbyterian minister. Nothing is known of his early years except that he went to sea, and by 1689 had become the captain of a privateer in the Caribbean. While in command of the ship Blessed William, he joined a squadron led by Captain Hewetson of the Royal Navy which raided the French island of Marie Galante and then fought a pitched battle with five French warships off the island of St. Martin. Unfortunately, Kidd’s crew were more interested in buccaneering than in fighting for their country, and soon after they dropped anchor at Nevis, they seized Kidd’s ship and sailed away without him. However, the Governor of Nevis was grateful for Kidd’s actions against the French and presented him with a recently captured French vessel, which was renamed the Antigua.

In 1691 Kidd arrived in New York in command of his new vessel. On May 16 he married a wealthy widow, Sarah Oort, and in due course they moved into a fine house in Pearl Street at the southern end of Manhattan Island, near the quays of the old harbor. For the next four years Kidd developed business interests, cultivated friendships with politicians and merchants, and did some occasional privateering. He seems to have become bored with this life, and in 1695 he sailed for England, hoping to make his fortune from privateering.

With the help of Robert Livingstone, a New York entrepreneur who arrived in London around the same time, Kidd set about looking for sponsors who would put up the money for a privateering voyage. After much lobbying they gained the support of Lord Bellomont, a Member of Parliament and a staunch supporter of the ruling Whig party. Bellomont was in need of money and was to play a key role in the story because he had recently been nominated Governor of Massachusetts Bay. The three men devised an unusual scheme for making money: they would form a syndicate, buy a powerful ship, and dispatch it to the Indian Ocean to capture the pirates who were plundering shipping and selling the stolen goods to merchants in New York. Bellomont agreed to find financial backers for the venture, while Kidd undertook to command the ship and to recruit the crew under the usual privateering system of «no purchase, no pay».

Bellomont persuaded four other Whig peers to become financial backers:

- the Lords Somers;

- Orford;

- Romney;

- and Shrewsbury.

Edmund Harrison, a wealthy City merchant and a director of the East India Company, also agreed to participate, and they approached the Admiralty for a privateering commission. At this date England was still at war with France, so there was no problem about obtaining a letter of marque which authorized the capture of French ships. This did not extend to the capture of Typical Activities Aboard the Pirate Ship, the Pirate Codepirate ships, but the shortcoming was overcome by issuing a patent under the Great Seal signed by the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, who happened to be Lord Somers. This second commission authorized Kidd to hunt down «Pirates, Freebooters, and Sea Rovers» and in particular four pirates who were named in the document:

- Captain Thomas Tew;

- John Ireland;

- Thomas Wake;

- and William Maze, or Mace.

The most surprising part of the whole deal was that the King himself was persuaded to take part in the venture. William III gave formal approval to the scheme and signed a warrant which authorized the partners to keep all the profits from Kidd’s captures, thus bypassing the usual arrangement whereby all prizes must be declared in the Admiralty Courts. The King was induced to agree to this unusual arrangement because Lord Shrewsbury arranged for him to reserve a share of 10 percent.

The vessel selected for the privateering voyage was the thirty-four-gun Adventure Galley. On April 10, 1696, the Adventure Galley anchored in the Downs, and the Thames pilot was dropped off. After a brief stop at Plymouth they set off across the Atlantic to New York, where Kidd hoped to make up the crew numbers needed. News of the privateering voyage rapidly circulated on the waterfront, and he had no problem in recruiting 90 more men. When he left New York on September 6, 1696, there were 152 men in his crew. Governor Fletcher of New York described them as «men of desperate fortunes and necessitous of getting vast treasure».

They spent a day at Madeira to collect freshwater and provisions, then headed south. On January 27, 1697, they dropped anchor at Tulear (Toliara), a small port on the west coast of Madagascar. Kidd stayed here a month to give his men time to recover from the voyage. Several were sick with scurvy. He then sailed north to Johanna in the Comoros Islands and from there to the nearby island of Mohilla, where he careened his ship. While there he lost thirty men to tropical disease. The survivors were now becoming restless. He had taken on more men during his various stops in the Indian Ocean, and a number of former pirates had now joined the crew. The «no purchase, no pay» arrangement meant that they must capture a prize soon or go home penniless.

Kidd decided to head for the Red Sea and see whether he could intercept one of the ships of the pilgrim fleet. He told his crew he was heading for Mocha at the mouth of the Red Sea: «Come boys, I will make money enough out of that fleet». This was not part of his brief and was not covered by either of the privateering commissions which he carried, and so would be difficult to justify to his backers. The pilgrim fleet left Mocha on August 11, 1697, under the protection of three European ships, one of them, the thirty-six-gun Sceptre, commanded by Edward Barlow, recently promoted from first mate following the death of the captain. Barlow is much revered today among maritime historians for the vivid journal which he wrote and illustrated describing his life at sea. Early on the morning of August 14, Barlow spotted the Adventure Galley closing with the convoy. Ominously, she was flying the red flag of piracy at her masthead. Barlow fired his guns in warning and raised the flag of the East India Company. The wind was light, so Kidd used his oars, steered toward a Malabar ship, and fired a broadside. Barlow was not prepared to lose one of his convoy. He lowered his boats and had his crew tow the Sceptre toward Kidd’s ship. He ordered his men aloft to yell threats and fired off his guns. Kidd lost his nerve. He retreated out of range and after a while abandoned all hope of capturing a prize and sailed away.

His situation was deteriorating fast. His ship was leaking, supplies were short, and his crew were becoming mutinous. When they encountered a small trading ship off the Malabar coast, Kidd fired a shot across her bows and came alongside her. What happened next was the turning point in Kidd’s voyage. The trader was flying English flags, and while Kidd was interviewing Captain Parker, her commander, some of Kidd’s crew tortured Parker’s men to find out where they had hidden their valuables. Several seamen were hoisted up on ropes and beaten with cutlasses. Kidd then seized provisions from Parker’s vessel and forced him to stay on board and act as a pilot.

News of Kidd’s attack on the pilgrim fleet and on the trading vessel began to circulate among the harbors of the region, and two Portuguese warships were sent out by the Viceroy of Goa to look for the Adventure Galley. For once things went Kidd’s way. He was able to cripple the smaller of the two ships with his guns and to escape unscathed. But the lack of discipline and the piratical state of his crew were clearly demonstrated when they called in at the Laccadive Islands. The local boats were seized and chopped up for firewood, the native women were raped, and when their men retaliated by killing the ship’s cooper, the pirates attacked the village and beat up the inhabitants. News of these atrocities reached the mainland and further added to the catalog of Kidd’s misdemeanors.

Two further events sealed Kidd’s fate. On October 30 an argument developed between Kidd and his gunner, William Moore. The men had been grumbling about the lack of prizes, and Kidd rounded on Moore, who was on deck sharpening a chisel, and called him a lousy dog. Moore replied, «If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so; you have brought me to ruin and many more». Kidd was enraged by this remark. He picked up an iron-hooped bucket and thumped it down on the head of the gunner. Moore collapsed on the deck and was heard to say, «Farewell, farewell, Captain Kidd has given me my last». The ship’s surgeon took Moore below but could do nothing for him. His skull was fractured by the blow, and he died the next day. Kidd was unrepentant. He said he had good friends in England who would save him from the consequences.

On January 30, 1698, the Adventure Galley finally came across a prize worth taking. Off the port of Cochin on the Malabar coast of India she intercepted the 400-ton merchant ship Quedah Merchant. She had taken on a cargo of:

- silk;

- calico;

- sugar;

- opium;

- and iron;

at Bengal and was heading north under the command of an English captain, John Wright. Kidd came alongside flying French flags. Most merchant ships on long voyages carried passes of several nationalities to avoid being claimed as a prize by privateers, and when Captain Wright saw Kidd’s French flags he naturally produced a French pass. This played straight into Kidd’s hand, because of course one of his letters of marque authorized him to attack and seize French ships. In fact the Quedah Merchant belonged to Armenian owners, and a considerable part of the ship’s cargo was the property of a senior official at the court of the Mogul of India.

Kidd informed Captain Wright that he was claiming his ship as a prize, and without more ado he escorted her to the nearest port in order to sell some of her cargo and raise much-needed cash. The value of the Quedah Merchant’s cargo was estimated at somewhere between 200 000 and 400 000 rupees. Kidd sold the bulk of the goods at the port of Caliquilon for around £7 000, and then headed out to sea to look for more prizes. He captured a small Portuguese ship, looted her, and kept her as an escort. He chased the East India Company ship Sedgewick for several hours, but she escaped. He then headed back to Madagascar and, in April 1698, the Adventure Galley dropped anchor in the pirate harbor of Sainte Marie. Already at anchor was the pirate ship Resolution under the command of Robert Culliford, who had spent the last year plundering ships in the Indian Ocean. Culliford was one of a group of mutineers who had killed the captain of the East Indiaman Mocha, and taken her over. If Kidd had not already turned pirate, he should have arrested Culliford and seized his ship, because that was exactly what his commission authorized him to do. Instead Kidd assured him he meant him no harm and joined him for a drink.

Kidd remained at Madagascar for several months, recuperating from the weeks at sea and waiting for favorable winds. The men insisted on a final share-out of the plunder, and some deserted and joined Culliford. Kidd decided to abandon the leaking and rotten Adventure Galley and took command of the Quedah Merchant, which he renamed the Adventure Prize. In the early months of 1699 (there is no record of the exact date) he set sail with a very much reduced crew of twenty and a few slaves. He headed for the West Indies and reached the little island of Anguilla in early April. There he learned that the British government, at the request of the East India Company, had declared him a pirate. No pardon was to be extended to him, and he was to be hunted down and brought to justice. He hastily stocked up with food and water and, after a stay of no more than 4 hours, set sail for a safer haven.

He selected the Danish island of St. Thomas, which was commonly used by pirates as a place to sell their plundered goods, and sailed into the harbor there on April 6. He went to see the Governor of the island and tried to persuade him to offer him protection from the ships of the Royal Navy. Governor Laurents was not prepared to risk a naval blockade of his harbor and refused his request. This encounter was later reported in London with some additions to the story: «Letters from Curassau say that the famous pyrate Captain Kidd in a ship of 30 guns and 250 men offered the Governor of St. Thomas 45 000 pieces of eight in gold and a great present of goods, if he would protect him for a month, which he refused».

Kidd returned to his ship, weighed anchor, and sailed onward. At the eastern end of the island of Hispaniola he sought refuge in the mouth of the Higüey River, where he moored his leaking ship to trees on the riverbank. Here he was joined by Henry Bolton, an unscrupulous trader with a shady past who had no qualms about dealing with the now- notorious pirate. Bolton and an associate agreed to buy the bales of cloth remaining in the hold of the former Quedah Merchant, and then bought the ship as well. Kidd purchased Bolton’s sloop, the Saint Antonio, and moved on board with the remnants of his crew and the profits from his various transactions.

At this stage it became clear to Kidd that his situation was desperate. The British authorities throughout the Caribbean were on the lookout for him. Back in November Admiral Benbow had sent a letter to the governor of every American colony requesting them to «take particular care for apprehending the said Kidd and his accomplices wherever he shall arrive». When the Governor of Nevis learned that Kidd was in the area, he sent HMS Queenborough to Puerto Rico to intercept him. Kidd decided that his only hope was to return to America and negotiate with his business partner Lord Bellomont, who was now Governor of:

- New York;

- Massachusetts Bay;

- and New Hampshire.

He set sail and headed north.

The Saint Antonio reached Long Island in June, and Kidd was reunited with his wife and two daughters after an absence of three years. Negotiations began with Bellomont in Boston, but the Governor was playing a tricky political game, having one eye on his own position and one eye on Kidd’s treasure. Interviewed by Bellomont and subsequently by the Massachusetts Council, Kidd gave a detailed account of the goods and cash he had acquired from his captures. He listed the:

- bales of silks, muslins and calicoes;

- the tons of sugar and iron;

- fifty cannon;

- eighty pounds of silver;

- and a forty-pound bag of gold.

Bellomont was aware that if he handled the situation badly, Kidd was a serious danger to his career. The most satisfactory course of action was to arrest him for piracy, which would clear him of involvement in Kidd’s exploits and enable him to take a portion of Kidd’s treasure in his role as Vice Admiral of the colony. When Kidd arrived for another meeting with the Council at Boston, he found the constable waiting at the door. The constable stepped forward to arrest him and Kidd ran inside the building, yelling for Lord Bellomont. The constable ran after him, seized him, and marched him off to the town jail, with Kidd shouting and protesting as they went. Although he had earlier promised Kidd that he would obtain the King’s Pardon for him, Bellomont was able to justify his change of heart because he had received specific instructions from England to arrest Kidd. Abandoned by the only man who could have saved him, Kidd faced a sealed fate. If he had hidden on one of the Caribbean islands or gone to earth on the mainland of America, he might have survived, as many other pirates managed to do, but he was now the scapegoat for all the acts of piracy committed by a generation of pirates in the Indian Ocean.

The news of Kidd’s exploits had been followed closely in London, which was not surprising as a number of influential people, including the King, the Lord Chancellor, and several Whig politicians, had originally taken a stake in his venture. When it was learned that Kidd had turned pirate, there were many Tory politicians who saw an opportunity to create a major scandal and bring down key members of the government. Interest was heightened by rumors that Kidd’s plunder was valued at more than £400 000. The East India Company demanded a share of the treasure to compensate for its losses in India and to repay some of the victims of Kidd’s raids. In December the whole matter was debated in the House of Commons, and there was a vote of censure for the Whigs’ handling of the affair. The Tories lost the vote, but the Secretary of State, Sir James Vernon, noted ominously, «Parliaments are grown into the habit of finding fault, and some Jonah or other must be thrown overboard if the storm cannot otherwise be laid». Needless to say, it was Kidd who was to be the Jonah.

Source: wikipedia.оrg

In September the news that Lord Bellomont had arrested Kidd reached London, and the Admiralty ordered a warship to be sent to Boston to bring him back to England. HMS Advice arrived at Boston in February 1 700 during a spell of bitterly cold weather. Kidd was escorted on board, and together with thirty-one other prisoners, he began the voyage back to England. By the time the Advice anchored in the Thames he was very ill. However, he managed to write a letter to Lord Orford, one of the sponsors of the voyage, and gave a selective and flagrantly biased account of his actions in the Indian Ocean. He maintained that he had only taken two ships, both of which had flown French flags. He claimed that his crew had forced him to commit piracy and had robbed him and destroyed his logbook and all his records. He concluded: «I am in hopes that your lordship and the rest of the Honourable gentlemen my owners will so far vindicate me I may have no injustice».

While the politicians, the lords of the Admiralty, the lawyers, and the merchants assembled their evidence and interviewed witnesses, Kidd was transferred from HMS Advice to the royal yacht Katharine at Greenwich. Worn down by months of solitary confinement and illness, and allowed no legal representation or even access to any relevant papers, he gave way to despair and contemplated suicide. Dreading the thought of death by hanging, he asked for a knife so that he could end his life. He was not to be allowed such a quick end to his troubles. On April 14 the Admiralty sent its barge down to Greenwich and Kidd was rowed upstream to Whitehall. That afternoon he was led into the Admiralty building in Whitehall and cross-examined by Sir Charles Hedges, the Chief Judge of the Admiralty, in the presence of Admiral Sir George Rooke, the Earl of Bridgewater, and other dignitaries. He repeated the arguments he had presented in his letter to Lord Orford. After seven hours of questioning, Kidd was led away to Newgate Prison, where he was to remain a prisoner for the next 11 months.

Even by eighteenth-century standards, Newgate was a nightmarish place in which to be confined. Situated on the corner of Holborn and Newgate Street, it was a forbidding stone building designed to house the criminal underworld of London while they awaited trial and death by hanging at Tyburn. Petty thieves and prostitutes rubbed shoulders with cutthroats and highwaymen. Wives and children were allowed to visit, and there was a relaxed attitude toward gambling, drinking, sex, and the keeping of pets and poultry, but this was offset by the severe overcrowding, the stinking smells, and the shrieks and shouts of the inmates. In 1719 Captain Alexander Smith described Newgate as a habitation of misery, «a bottomless pit of violence, a Tower of Babel where all are speakers and no hearers».

On March 27, 1701, Kidd was allowed a brief respite from this hellhole. He was marched through the streets to Whitehall in order to be examined at the bar of the House of Commons, the first and only pirate in British history to have to explain his actions before the assembled Members of Parliament. He was hardly in a fit state to do so. Depressed, disheveled, and suffering the ill effects of more than two years of imprisonment in horrendous conditions, he must have been a pathetic sight. No records of the session have survived, and all we know is that an attempt to use the occasion to impeach Lord Somers and Lord Orford failed. A second examination by Members of Parliament followed on March 31, and Kidd was returned once again to Newgate.

By this time the lawyers had prepared their case. Henry Bolton, who had bought the Quedah Merchant from Kidd in Hispaniola, had been tracked down and brought to England for questioning. Coji Babba, an Armenian merchant who had been on board the Quedah Merchant during Kidd’s attack and had lost all his goods, was sent from India by the East India Company so that he could give evidence for the prosecution. Kidd’s two slaves Dundee and Ventura had been questioned, and piles of papers had been assembled from Lord Bellomont and everyone connected with the case. All that remained was the trial, which was scheduled to take place on May 8 and 9 at the Old Bailey.

Kidd had two weeks to prepare his defense. He asked for his papers to be sent to him, and in particular requested his two privateering commissions, his original orders from the Admiralty, and the two French passes he had been given by the captains of the Quedah Merchant and one of the other ships he had taken. Some documents were brought to him, but mysteriously missing were the French passes.

When the trial began before Lord Chief Baron Ward and four other judges, Kidd found himself facing a formidable list of charges. He was accused of the murder of William Moore, the man he had killed with the iron-hooped bucket; of piracy and robbery of the Quedah Merchant; and of piratically attacking and taking four other vessels and stealing their cargoes. On the matter of the murder charge, Kidd maintained that his crew was on the verge of mutiny at the time, that he was provoked by Moore, and that he had never intended to kill him. On the piracy charges, Kidd argued that he had a commission to take French ships, and insisted that if the French passes could be found, his innocence would be proved. However, the evidence assembled by the prosecution was formidable, and the witnesses for the prosecution were well briefed. Kidd blustered his way through the proceedings, but the verdict was inevitable. The jury found him guilty on all the charges, and the judge sentenced him to death by hanging. When he heard the sentence, Kidd said, «My lord, it is a very hard sentence. For my part, I am the innocentest person of them all, only I have been sworn against by perjured persons».

But what of Kidd’s plunder and the rumors of buried treasure? Kidd traded some of his cargo at a port in the Indian Ocean, and much of the rest he sold to Henry Bolton in Hispaniola. He bought the Saint Antonio for 3 000 pieces of eight, and acquired 4 200 pieces of eight in bills of exchange and 4 000 in gold bars and gold dust. He therefore sailed north with 8 200 pieces of eight in portable form, along with an unknown amount of goods and treasure loaded on his newly acquired sloop. When he arrived in New York, he may have handed some of his fortune to Mrs. Kidd and his friend Emott.

While preliminary negotiations were taking place with Lord Bellomont, Kidd moved his ship from New York harbor to the eastern end of Long Island, where he sailed back and forth near Gardiners Island. For some weeks the ship lingered between Gardiners Island and Block Island, and during this time three sloops came alongside to take off some of Kidd’s crew, together with their sea chests and their share of the cargo. We know that Kidd sent Lady Bellomont an enameled box with four jewels in it. We also know that Mrs. Kidd sent a six-pound bag of pieces of eight to Thomas Way, and that Kidd sent several pounds of gold, believed to be worth £10 000, to Major Selleck in Connecticut. But the greatest amount came into the hands of John Gardiner, the proprietor of Gardiners Island, and it was this which was to lead to the legend of Kidd’s buried treasure. On two occasions Kidd landed on the island; he bought food from Gardiner, and left: behind five bales of cloth, a chest of fine goods, and a box containing fifty-two pounds of gold. This was probably his security in case things went wrong.

As soon as Kidd was safely locked up in Boston jail, Lord Bellomont made strenuous efforts to locate and retrieve the treasure, which was now scattered in various locations around New York, Boston, and the West Indies. Mr. Campbell’s house in Boston was searched, and 463 ounces of gold and 203 ounces of silver were removed. John Gardiner sent Bellomont eleven bags of gold and silver. In the end 1 111 ounces of gold, 2 353 ounces of silver, forty-one bales of goods, bags of silver pieces, and various jewels were collected and sent on board HMS Advice for dispatch to England. The total value of this was reckoned to be £14 000, a handsome sum, but nothing like the £40 000 Kidd had led Bellomont to expect, and a tiny fraction of the £400,000 Kidd was rumored to have plundered in the Indian Ocean. Although Henry Bolton had been arrested by the captain of HMS Fowey, there was no sign of the goods he had acquired from Kidd in the West Indies. The Quedah Merchant, abandoned in Hispaniola, was set on fire, and the burned-out hulk was left to rot on the shore of the river estuary. Over the years people have tried to find the remnants of Kidd’s treasure and have carried out searches on Gardiners Island and many other locations, but without success.

Read also: Historical Facts About Famous Women Pirates

We know more about Kidd’s treasure than about any of the other pirates of his day simply because of the public interest surrounding his capture and trial. Other pirates of his day may have amassed more plunder than he did, but the evidence is fragmentary. Bartholomew Roberts’ biggest haul was probably the cargo of the Portuguese ship he looted in his first year of piracy. Blackbeard plundered around twenty ships during his two years as a pirate, but none of his prizes were spectacular in terms of treasure. After the battle at Ocracoke Inlet the loot recovered from his vessels and ashore in a tent was:

- «25 hogsheads of sugar;

- 11 tierces;

- and 145 bags of cocoa;

- a barrel of indigo;

- and a bale of cotton».

This, together with the sale of Blackbeard’s sloop, came to £2 500 – not a very impressive sum to have amassed during such a famous piratical career.

Captain England captured a number of rich prizes in the Indian Ocean. In 1720 he came across a Portuguese ship of seventy guns at anchor among the Mascarene Islands to the east of Madagascar. She had been badly damaged in a storm and put up no resistance when attacked by the pirates. Among the passengers on board was the Viceroy of Goa. According to Johnson’s General History of the Pirates, the value of the diamonds on the ship was between $3 million and $4 million. He tells how the pirates sailed on to Madagascar, where they careened their ship and shared out the plunder, which worked out at forty-two diamonds a man. Henry Avery’s capture of the Ganj-i-Sawai was in a similar league, and the treasure looted from her was variously estimated at between £200 000 and £350 000. Most pirates had to be content with very much more modest plunder.

Apart from Kidd’s treasure, the best-documented booty from the great age of piracy is that looted by Sam Bellamy. Excavations on Bellamy’s ship the Whydah have brought up from the seabed an impressive quantity of coins, gold bars, and African jewelry. There are 8 397 coins of various denominations, including 8 357 Spanish silver coins and 9 Spanish gold coins, which together add up to 4 131 pieces of eight. There are 17 gold bars, 14 gold nuggets, and 6 174 bits of gold, and a quantity of gold dust. The African gold includes nearly four hundred items of Akan jewelry, mostly gold beads, pendants, and ornaments. No one will put a precise value on this and the press reports that the Whydah treasure is worth $400 million are wildly speculative, but the excavations have shown beyond doubt that some pirates really did lay their hands on large quantities of gold and silver.

The lure of treasure was always one of the most powerful motives for becoming a pirate. With riches like those acquired by Henry Morgan, Henry Avery, Captain Kidd, or Sam Bellamy a man could escape from the harsh life of the sea. He could squander his money on whores or pass his days drinking in some convivial tavern. He need never more risk death from malaria or yellow fever on the coast of Africa while his ship waited for a consignment of slaves. He could feast on fresh meat and good wine instead of moldering ship biscuits, salt pork, and evil-smelling beer.

Sailors were attracted by the tales of pirate kingdoms in Madagascar and the West Indies, where all men were equal, where everyone had a vote in the affairs of the pirate company, and where the plunder was fairly shared out. And for the more adventurous, piracy offered the chance to leave the gray, cold waters of the North Sea or the Newfoundland Banks and explore the warm blue waters of the Caribbean.

Some men were driven to piracy from sheer necessity. Two of the most dramatic increases in pirate activity took place when peace was declared after long periods of naval warfare and large numbers of seamen were out of work. When fifty years of hostilities between England and Spain were finally ended in 1603, hundreds of seamen from the Royal Navy and from privateers were thrown on the streets. Their only skill was in handling a ship, and many turned to piracy. For the next 30 years, shipping in the English Channel, the Thames estuary, and the Mediterranean was ravaged by pirates.

The second surge in piracy took place in the years following the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, which brought peace among England, France, and Spain. The size of the Royal Navy slumped from 53 785 in 1703 to 13 430 in 1715, putting 40 000 seamen out of work. There is no proof that these men joined the ranks of the pirates, and Marcus Rediker has pointed out that most pirates were drawn from the merchant navy, not the Royal Navy; but many contemporary observers believed that the rise in pirate attacks in the years after the Peace of Utrecht was due to the large numbers of unemployed seamen. They particularly blamed the Spanish for driving the logwood cutters out of the bays of Campeche and Honduras after the Treaty of Utrecht, and they also blamed the privateers. Many privateering commissions had been issued in the later years of the seventeenth century, particularly in the West Indies. Peace put an end to this, and the Governor of Jamaica warned London of the likely outcome: «Since the calling in of our privateers, I find already a considerable number of seafaring men at the towns of Port Royal and Kingston that can’t find employment, who I am very apprehensive, for want of occupation in their way, may in a short time desert us and turn pirates».

The speeches of condemned pirates awaiting execution provide a further insight into what induced men to take up piracy. Some blamed the cruelty of captains, but many blamed drink for leading them astray. Before he was hanged at Boston in 1724, William White said that drunkenness had been his ruin, and he had been drunk when he was enticed aboard a pirate ship. John Archer, who was hanged on the same day, admitted that strong drink had hardened him into committing crimes that were more bitter than death to him now. But it was the lure of plunder and riches which was the principal attraction of piracy, just as it has been for every bandit, brigand, and thief throughout history.