Learn about portable boats and how to transport them. Discover the types of portable boats available, their benefits, and tips for easy and safe transportation. Ideal for adventurers and boating enthusiasts looking for convenience and mobility.

You’ve heard the old saying that travel is broadening. In my opinion there’s much truth to it. For example, a recent trip I made did in fact broaden my outlook on one aspect of the vast boating world – small, portable boats.

We were driving to New York City to attend the boat show held there. As we cruised along Rt. 95 through the Pelhams on the city’s northern outskirts, we noticed more and more new high-rise apartment houses – and from there on all the way into the city we saw more and more apartments.

Being country boys, we were appalled by this jamming-together of humanity. Surely, we said to one another, we’d go nuts if we had to live in one of those buildings. No basement in which to store outboard motors and tinker with surf rods. No backyards in which to park and hose off trailered boats. Yechhhh!

We arrived at the boat show before it was ready to open to the public and, using our press passes, we went in to watch the bustle of activity attendant to getting things ready. On the ground floor I watched truckers and riggers straining and coaxing to get big boats off of flatbed trailers and into position on the floor. Then taking the elevator to the fourth floor, I became aware of the fact that assorted exhibitors of inflatable boats were also bringing in and setting up their displays.

Matter-of-factly and quite without any fuss, they came out of elevators, walked to their booths with large bags in hand, and opened them. Out came floppy masses of orange and gray fabric. Plugging in electric air pumps, they stood unconcernedly by while their assorted boats took shape before my surprised eyes.

By golly, I mused, what with all these apartments and condominiums springing up and inflatable boats coming into boat shows with all the matter-of-fact ease of a pelican swallowing a small fish, it’s about time I paid some attention to the portable boat field!

It’s obvious that despite the rapidly growing popularity of large, seagoing fishing boats, many fellows who love the sea and fishing dearly just cannot become owners of them because of where they happen to live – no place to keep one when it’s not in use. And, of course, even people who find it possible to own a larger craft often also own smaller craft, for the valid reason that the little ones can go into shallow and confined places in quest of fish where the big boys dare not poke their bows.

Boaters who frequent marinas and boatyards tend to look down their noses at inflatable boats.

“Who wants to spend all his time pumping one up or folding it down?” they snort.

They do have a point there and it is proven by how often one sees inflatables being transported in inflated condition on the tops of passing automobiles. But one has to admit, on looking around, that inflatables are in fact becoming more common and people are doing surprising things with them.

They originated in Europe, where housing has always been much smaller and more crowded than in America. Over there, where people travel in busses and trains or on small motorcycles so often, the inflatables make as much sense as folding beds make to the dweller in a smaller American apartment. And now, as the small family farms go out of business and more people move to the city, the inflatable boat is really beginning to catch on here. Even the big-boat people are beginning to look at them closely.

Anyone who has tried to stow a dinghy aboard a smaller powerboat, or to tow one behind a fast boat, is ripe to see the sense in using an inflatable as a tender. It can be stowed in a locker, under a seat or in some other such place where it is out of the way and no nuisance at all – but it’s there and ready for use in a short time when needed. Back when space in natural mooring sites was easy to find, people used tenders all the time to row out to their moored boats. Now such space is as scarce as farm tractors in Manhattan. More and more boats are kept at marina docks and tenders are used only for going ashore occasionally when out cruising. Here, the inflatable walks off with the handiness trophy.

The type comes in an amazing range of sizes and styles, and you can no longer refer to them as “rubber boats.” A variety of tough and durable modern materials are being used by various makers. Stories are endless of their exploits under widely varying and often difficult conditions – in the arctic and tropics, on the open sea and on the wild rapids of western rivers.

Cousins to the inflatables are the folding boats. They live under a handicap, so to speak, in that they do not have such a big, ready-made market in America to keep production thriving and so make them a viable business proposition. The folding or collapsible boats that are made in Europe tend to be long, narrow, kayak-type craft meant for river cruises. You need a clear, flat space a little bigger than the boat itself to lay out and fit together the frame members and “skin,” so this inhibits their use as yacht tenders. The inflatables are easier to “put together” aboard a yacht, so they sell widely instead of just in river country.

Most imported European foldables don’t excite fishermen. A variety of types appear on the market in the U. S., incorporating assorted and often ingenious folding methods. We’ve seen some with quick-acting aluminum frames, we’ve seen three-piece “sectional” craft whose sections clamp together to form rowboat-like craft, we’ve seen folding craft made of plywood and aluminum sections “taped” together so they will fold flat and open much like a paper hat. Many of these boats are clever, and some of them “open and close” with surprising speed and ease.

The fly in their ointment is that it’s hard for a small manufacturer to make a go of producing them. The emphasis in the last 25 years has been on power, speed and styling, so it’s hard to get marine dealers to stock them. Dealers shy away from them because they feel they will sell too slowly. It’s now a chore to design a fold-flat boat that conveniently and economically incorporates the safety flotation wanted by government agencies. For these reasons, collapsible boats are what you could call the runt of the litter in the field of small, portable craft.

In recent years the “john boat” has become extremely popular. It’s not a folding or collapsible boat, but it’s gosh-awful cheap and for that reason widely sold by all kinds of retailers, including discount houses. We’ve seen them priced as low as $69,00 for a ten-footer. You can’t even buy the plywood, screws and paint for an eight-foot pram for that amount of money. The cheapness of these boats has put them into the hands of people who have very little boating knowledge. They just want an inexpensive craft in which to go pan fishing. So, regrettably, the john boats have racked up a poor record that bothers the safety authorities and makes them wonder what to do about the problem.

The john boat originated in the Ozarks, which isn’t what we could call the home of the seamen. It was made narrow for float-fishing trips down quiet rivers. The guide handling it would want to switch his oar from side to side to “rudder” it, much as a canoeist does. You can’t conveniently do that in a boat five or six feet wide. Smaller john boats are seldom any more than about three feet wide across their bottoms. Taking six feet as being the height of the largest men likely to use a john boat often, you have the man’s center of gravity (located approximately at his navel) as about four feet above deck level.

Source: unsplash.com

Between a hull three feet wide under a center of gravity at that level, and one four feet wide, you can figure out mathematically that there’s a substantial increase in stability when a twelve-foot john boat is compared to the wider twelve-foot outboard skiff. These aluminum john boats were not designed, they were just copied somewhat mindlessly from the wooden originals. Used by experienced Ozark river men on quiet waters, they may have been safe. Stacked by the scores on big trailers and shipped to far-flung markets, they got into the hands of people who knew nothing about them to begin with and who then started to use them on lakes, bays and other open waters for which they were not suited, period.

Ever hear of “longitudinal stability?” Just as assorted boats have differing rolling characteristics, depending on their cross-sections and location of their vertical center of gravity, boats will pitch differently depending on their hull length and shape as seen from the side.

But as seen from the side, most of the length of a john boat’s bottom is as flat as the floor under your chair. The bottom up forward is curved upward just enough to let a wave go under it … and start to lift. But all that dead flat bottom from amidships aft strongly resists being pushed down. That being so, the forward section does not want to lift easily. As the chop freshens, you get more and more of a tendency for waves to give up hope of trying to lift that stubborn bow, and they start slopping over the top of it.

The Ozark rivermen don’t need or want the Gloucester schooner man’s banks dory for their float trips. It would be nice if they had kept their john boats home on their placid rivers where they belong. But, because of its powerfully attractive low price, this type of boat did spread and there’s nothing we can do about it, except to do what we individually can to broadcast the word that this type isn’t an open-water craft and must be used with caution. The longer the john-boat, the more its bow is apt to resist lifting.

Read also: Essential Tips for Boat Maintenance

Canoes for the last several years have been growing steadily in popularity. Their “home waters” are of course the nation’s thousands of small lakes and rivers. Presumably, their ascending popularity has its roots in the same back-to-nature-and-simplicity trend that is responsible for the boom in bicycling and back-packing. Their increasing availability is bound to lead more and more people to try using them for salt water fishing, if only on the spur of the moment such as when one is casting from a beach in the evening, spots fish feeding a bit beyond casting range, and rushes to launch Sister’s canoe that is laying handy nearby.

Propelled by arm power or an electric trolling motor, a canoe certainly can enable a salt water fisherman to slip up on the haunts of certain species without spooking them, especially inside bays, coves and inlets. Shaped to propel easily under low power (a man can develop about one-quarter horsepower for brief spurts), a canoe will slide along somewhat faster under electric power than will the typical planing-hull outboard boat with its broad, drag-creating transom.

All that I can say is, if you have the notion that a canoe could help your fishing efforts, learn something about canoes. The Boy Scouts of America print a merit badge pamphlet on canoeing that covers the basics quite well, and the American Red Cross has a much thicker paperback book called “Canoeing” that goes into a lot more detail. Canoe dealers who really know and love these boats usually have these publications in stock, otherwise contact your nearest Boy Scout or Red Cross office to get on the trail of a copy.

Here’s an example of the nuances of canoes and canoeing. Aiming at the mass market, some pioneers in the aluminum canoe business felt they would be wise to produce a more stable craft than those offered by the traditional old-time wood and canvas canoe makers, who aimed at the canoe enthusiast market. So they designed their canoes to have bottoms a little flatter across the bottom amidships, and a little wider in the beam in the region just below the seats. This inconspicuous change in shape made their canoes noticeably more stable, at the expense of making them propel a little slower under arm power. Put one of these canoes alongside a fine old wood and canvas model and this difference will be easy to see – once you know what you are looking for.

With many small firms popping out fiberglass canoes, you find that they take an assortment of metal and wooden models as their patterns. Often they are fiberglass men first and boatmen a distant second and know nothing about the fine points of canoe shape. So, especially in the fiberglass canoe field, you will find everything from admirable copies to abominable abortions being offered by dealers. Only by knowing something of canoes can you make a happy choice.

Boat Outboard MotorsOutboard motors have been used on canoes since well before World War II. In an old book on outboard motors I was browsing through recently, I came upon an interesting table of performance capabilities of various boats powered with assorted motors. Back in those days there were tiny, flyweight outboard motors such as the half-horsepower and one-horsepower Evinrude “Pal” and “Mate.” Would you believe, this table shows that when propelled with such motors a typical canoe could do up to 27 miles per gallon of gas! You would be surprised to see how a modern two-horsepower outboard can make a sleek canoe scoot along.

No doubt about it, a man can do a lot of fishing inside a bay or in the channels of a tidal marsh on a gallon of gasoline, if he uses one of these rigs. And, lashed on top of a car, a canoe causes remarkably small wind resistance, to the benefit of the car’s miles-per-gallon figure. After all, bush pilots in the north woods often lash canoes to the float struts of seaplanes and haul them to distant lakes at a hundred miles an hour.

There are two ways of attaching small motors to canoes, side bracket and stern mounting. The side bracket tends to give the willies to powerboat men, who imagine the offcenter thrust line will make the canoe cruise in circles. But thanks to the length of the canoe’s hull and its long keel, there is surprisingly little effect on course keeping ability. Try it and see! Motor weight is balanced simply by the helmsman’s sitting a trifle to the other side of the centerline. Too heavy a motor will make the canoe flop over when empty, and too powerful a one will spring a surprise on you the first time you turn it too much and too abruptly with its steering handle – the deflected propeller thrust line will make the craft roll wildly.

When it is anticipated that a small motor will be used on the canoe most of the time, it’s common to clip off the pointed stern and fit a small transom. This affords centerline motor installation, but there are still quirks. Motor weight so far aft tends to depress the stern of the canoe, which has little buoyancy under the motor. Controls may be more awkward to reach. When a lone occupant rides in the stern, his plus the motor’s weight can put the stern down and bow up. Because the hull is narrow under the stern seat and motor, stability is marginal. Putting a passenger up forward brings it back into good balance. You deduce from this that square-stern canoes are as a rule chosen for long trips on chains of lakes, where a companion in the forward seat and a load of duffel amidships will normally be present. For intermittent solo fishing, the bracket and side-mounted motor might be your choice.

Any canoe used in coastal waters can expect to meet waves, either the chop blown up by wind, the swell coming in from seaward, or the wakes of larger powerboats. The long, sharp forebody of a canoe does not lift to larger waves as well as does the flared bow of a powerboat, especially when it is held down by the weight of an occupant in the forward seat. When bucking into waves, use good seamanship – have your bow passenger move aft a bit so the bow will rise quickly and easily to the waves. If the wind springs up or you must run broadside to waves, all hands should slip off the seats and sit on the craft’s floor. You’ll be amazed at how much more stable the canoe will become with this lowering of its center of gravity. Tricks like these have enabled experienced men to make remarkable voyages in canoes.

Aluminum boats with wide transoms for outboard motors continue to be popular, despite the craze for “bass boats” in the hinterlands having pushed them off of magazine pages. Growing interest in coho fishing on the Great Lakes has prompted several aluminum boat makers to come out with big, deep models in the 16 foot range which many an economy-minded salt water sportsman might look at with a gleam in his eye.

Growing interest in small automobiles makes many a would-be boat owner wonder about their ability to haul trailered boats. The rule-of-thumb commonly used to gauge a car’s trailer towing ability is that total weight of the trailer and its load should not be much over 50 % of the loaded weight of the car. It’s partly a matter of safety – a too-heavy, brakeless trailer can “take charge” of a too-light tow car when a sudden stop is necessary. Four-speed transmissions common on small cars seem to take care of the pulling and accelerating matter well enough. We are seeing more and more of new materials that hold out the promise of lighter trailer boats.

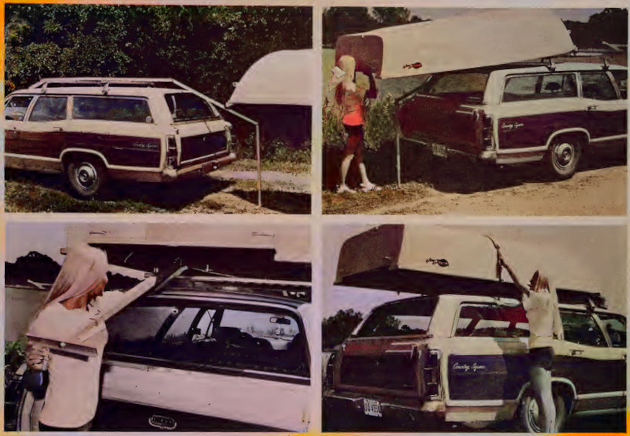

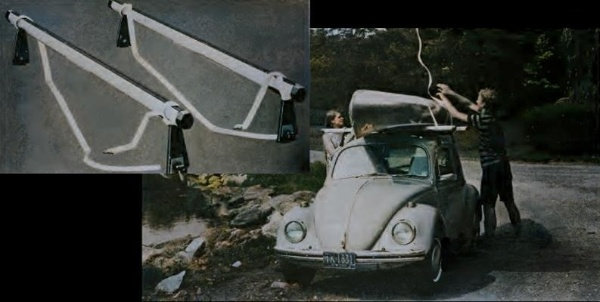

Many firms make cartop carrying racks, easy-load devices and trailer hitches designed to fit quickly and securely onto all popular makes of boats. Few marine supply stores carry a full line of this type of equipment, partly because the cartons are big and take up storage room, partly because demand tends to be scattered and sporadic.

Whether you live in an apartment or mobile home park, drive a midget car or have little spending money left after paying your offspring’s college tuition, there is a little boat somewhere that you can manage and which will enable you to get out on salt water under reasonable conditions to enjoy a bit of fun and put some tasty fish on the table. Good luck and good fishing!