Explore the fascinating history of the first boats with outboard motors. Discover how these innovative vessels revolutionized boating and transformed marine travel and recreation.

To understand and judge boats knowingly, a person must have a good understanding of how they have developed down through the years. No boat type “just happens”. New types come into being over a period of time as experience and technical progress accumulate and lead, over a period of time, to the gradual perfection of an idea.

Consider the aluminum canoe as a readily-understood example. If we gave a Tibetan mountaneer a pair of tin snips, a rivet gun and a pile of sheet aluminum and told him to go ahead and construct his notion of a craft intended for moving over the water, he surely would not come up with anything we’d recognize as a canoe. Before the aluminum canoe there had to be cedar-and-canvas ones, and before those, there had to be birch bark ones.

And the birch bark canoe, in its final form, no doubt developed over a period of many Indian generations from the day some long-dead Indian got the notion that an oversized birch bark basket would float him across a river, built himself one and discovered its shortcomings in the handling and paddling departments.

This leads up to the observation that, by golly, a distinct new form of fishing boat has been developing right under our noses and is now well established as a useful if unnamed type.

Now we must go back into outboard history to trace a story of development. The first outboard motors were low-powered mills designed to push the common rowboat, which had a low-speed displacement hull easily driven by oars. As outboard motors became more common in the mid-1920’s, boats designed especially to be propelled by outboard motors came into being. They had wider, flatter sterns and flatter bottoms aft to support the weight of motor and operator. This change, it was soon discovered, enabled them to rise in the water, as they gained speed, and skim switftly along over its surface, unencumbered by the displacement hull’s wave-making tendencies that put a limit to its speed potential.

By the beginning of World War II, the planing-type outboard hull was commonplace. When a lone occupant was aboard, he had to sit in the stern to grasp the motor’s steering handle. As this concentration of weight aft put the stern down and Boat Performance Factors Explained: Key Metrics and Analysis Guidehurt performance, occasionally a speedster was equipped with a steering wheel and a bowden-wire control for its throttle so that the driver could move forward a little farther and improve balance. This idea was sometimes applied to larger, general-purpose outboard boats, but it wasn’t too convenient or safe; it required some fast stepping to start the motor and scramble forward to the controls in time to keep from ramming something when the direct-drive motor caught and started pushing.

Shortly after World War II, the first gearshift motors were introduced to a fascinated public. This brought onto the market tailered-to-fit, easily installed, dependable remote controls that made forward seating for the driver really feasible. Soon everyone was sitting up forward just like in an automobile, with hood-like deck and wrap-around windshield to heighten the impression of motoring on the water.

While this new forward seating positiion had things in its favor, it had other things against it. Seated up forward, the driver of a comparatively light boat that skims over the water’s surface gets a shaking-up when he seeks to maintain normal high speed over choppy water. While the forward deck and windshield offer protection from wind and spray, they are also rather in the way when the time comes to handle an anchor line or go ashore on the beach, or stand up to cast forward. While fending off spray and water, a foredeck does render useless, for any purpose other than storage, about one-fourth to one-third of a hull’s length.

Also, when two or three persons are riding well forward, and the boat is slowed down to negotiate rough water, the bow tends to settle in the water, and there is an ever present possibility of “submarining” into a steep, oncoming wave. And it was always difficult to decide on a really happy location for extra-capacity fuel tanks.

Locating a tank under the foredeck parts it in the section of the boat subject to the most severe up-and-down action on rough water, with consequent strain on tank supports and the hull bottom. Location in the stern poses problems of hull balance, what with a motor and battery there already. Location under the seats amidships, or under the side decks, brings on tough problems of space and mechanical details.

For example, it is often hard to find a tank that will fit inside the base of a stock back-to-back seat; it may be hard to neatly fit a filler cap on a narrower side deck; a built-in fuel quantity gauge may be out of sight when its tank is under a seat – and so on.

We can safely assume that these assorted deficiencies were noted by the serious fishermen who wanted an outboard boat made just so for fishing, with no frills or nonsense in its makeup. In recent years, the publicity spotlight has been on deep-vee and cathedral hulls, and this perhaps has dimmed widespread realization of the fact that a new type of fishing boat has been developing. But take a good look around today, and you’ll realize all of a sudden that a new style of boat is in fact becoming more popular in leaps and bounds. Like so many things afloat, it has come out of the heads and small shops of men who got their ideas out on the ocean and not out of the tips of artists airbrushes.

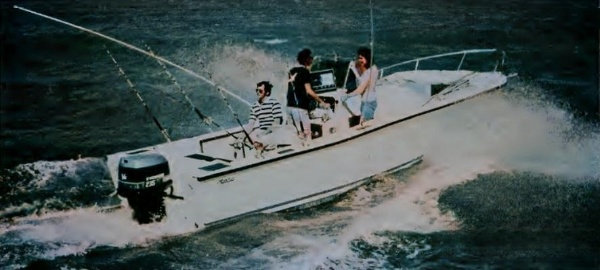

Everywhere you go along the coasts these days, you are seeing big and able outboard boats from 18 to about 22 feet long, and similar stern drive boats up to about 24 or 25 feet, that all follow a similar pattern. They are unmistabably boat-shaped outside, and clearly laid out for business inside. They’re as open as the old time fishing skiff – although many times roomier and more stable by reason of being larger – and they have a control console located in the middle of the open cockpit at more or less amidships.

The operator can sit or stand at the steering wheel as he prefers. You’ve probably seen enough boats like this already, so you are familiar with their appearance and layout – even if it hasn’t struck you that they do indeed represent a distinct new type of fishing craft.

To appreciate that this is, in fact, the case, one must understand the reasons behind their features. Ideas from various phases of boating were used in their development – well-proven ideas from the field. Drivers of fast ocean racing speedboats long ago abandoned seats in favor of the standing position, so that their flexed knees could absorb the jolts of connecting with big waves at high speed. The amidships control station would have been impossible a score of years ago; it is feasible today thanks to highly-developed and reliable motor and steering remote controls based on enclosed push-pull cables.

Read also: Characteristics of Different Types of Construction Materials

The comfortable upholstered seats, often in the form of full-swivel fishing chairs with gimbals for rod butts, would be prohibitively expensive if specially made in small volume for one boatbuilder. But the size of today’s marine industry is such that seats of this kind are now available to boatbuilders as stock items from firms which have found it possible to make a viable business of specializing in marine seating. The same can be said of the metal hand rails, seen in various locations on these boats which make standing up safe.

When separate fuel tanks averaging six gallons capacity were introduced some years ago, outboard motors were fitted with pumps to draw fuel from these tanks to the carburetor. This opened the door to the manufacture of long-range tanks of 18 and 24 gallon capacity – which was a vast improvement both in convenience and safety over the early practice of carrying spare gas in tin containers and pouring it messily into an on-the-motor tank, while one’s boat pitched and rocked on the ocean’s waves. Some of these new boats have stern drive engines, and it occurs to you that it wasn’t until stern drives became popular and readily available that it was feasible to have both a control console and gas tanks located in the approximate center of the cockpit.

So you see, things like the foregoing had to come along and be evaluated by practical boatmen before the kind of boat we are discussing could take shape. The type (at least in the size range we are discussing) seems to have been developed in Florida although it has to be admitted that open craft with mid-cockpit control consoles have been seen for a number of years in more northerly climes. It’d probably take some researching to determine who actually thought up the basic idea. Anyway, the boats we are discussing represent a collection of ideas put together to create the whole.

At present the best-known names in the field are Aquasport, SeaCraft and Mako, all hailing from Florida and producing Manufacturing of Fiberglass Boats and Design Featuresfiberglass craft. These boats run from about 19 to 22 feet in length. Aluminum versions of the same general layout, usually on the smaller side in the 16 to 19 foot range, are being made in the midwest by firms such as Mirro, Starcraft and Lund, and are finding their way to coastal areas. Other makers are getting into the act these days, and ere long, a man should have quite an array of makes and models from which to choose.

The Florida specimens, and others as well, are definitely open-water craft, and the aluminum ones, while without doubt capable of taking care of themselves and their occupants on rough water, appear to be directed more toward the new and growing legion of Great Lakes coho fishermen. But those lakes can become extremely rough at times, and what can survive there can be taken to sea without sweating gum drops.

In the 19 to 22 foot outboard and 20 to 25 foot stern drive versions, all these boats are definitely meant for ambitious trips well offshore after game fish. For all practical purposes they are completely open boats, which at first creates some apprehension about venturing many miles out on the ocean. But when you analyze how things shape up, your confidence comes back.

While pointed and able to divide waves like a boat should, the bows of most of these boats have a good amount of flare. That means that the higher the water climbs on them, the more powerfully does it lift on them. Fuel, passenger and powerplant weights are concentrated well aft in the hulls, recentuating the built-in ability to climb easily over tossing seas. Most of these boats could easily carry a dozen or a score of people across a pond in safety, such being their hull volume and buoyancy, but the normal load on a serious open-water fishing trip is something between two and four persons. This is a rather light load and leaves the boats with reserve capacity to crawl ably over rough seas.

Also, most of them have cockpits that are self-bailing – at least to a degree – and even when full self-bailing isn’t incorporated, the installation of one of today’s electric bilge pumps assures that water that comes over the sides will be kicked overboard again quite promptly. Here we will digress for several paragraphs into the subject of self-bailing cockpits, for there is more to it than most people realize, and an appreciation of the matter’s diversities is needed to evaluate the boats we are talking about realistically.

When somebody tosses off the phrase “Self-bailing cockpit,” there is a tendency to take it for granted that a boat with such a cockpit is bound to be terrifically safe and able. But alas, it isn’t that way! Some self-bailing cockpits will save you any time, under any circumstances, but sometimes self-bailing cockpits don’t work quite as one imagined and then panic takes over.

People hear or read that some trans-Atlantic sailing yacht, or whatever, has a self-bailing cockpit and exclaim,

“I’m going to have one of those in my next boat too!”

They fall for the first motorboat they find which is said to have such a cockpit. It occurs not to them that there is a gray area in the picture, and one day they are profoundly shocked to find cockpit water creeping steadily up their legs!

Now I am going to make you exclaim: “Why didn’t I think of that before!” The cockpits of medium and large-sized sailing yachts amount to relatively small bathtub-like depressions in decks that otherwise shed rapidly all green water that falls on them. The weight of water that can be contained in such a self-bailing cockpit is relatively small compared to the hull’s overall carrying power, and when green water does land in such a cockpit it won’t put the boat under. Also, such a cockpit is apt to be one or two feet above the waterline and there is ample hydraulic head to make water drain from it at a fairly rapid rate.

Now consider a larger inboard-engined pleasure boat. Its hull is high-sided enough so that the cockpit floor can be located a foot or so above the waterline, without at the same time having it so high in the boat that the cockpit would seem low-sided and easy to fall out of. If the bulkhead and door separating the cabin forward from the cockpit is fitted with several scuppers along its port and starboard edges of fairly generous size, then we have a self-bailing cockpit that will take quite a lot of green water and let it drain out promptly enough to keep things under control.

When a weekend group of perhaps five or six people get aboard, their weight is such a small proportion of the total that it makes the boat settle in the water imperceptibly. If the engines are Complete Guide to Below Deck Sailboat Systems: Ventilation, Marine Heads, Water Systems and morebelow decks and the hatches are snug, the engine compartment will be kept dry, and if the stern tends to settle under a load of water in the cockpit, gunning the engines will push the boat along and hold the stern up long enough for the water to drain.

The problem in boats in the large outboard and small stern drive size range revolves around the matter of what level to have the cockpit floor height. Every additional inch you put it higher will make water drain out faster, and will get you farther away from the Achilles’ heel of having water come in through the drain holes when, because of load or trim, the boat goes down a few inches. But you also put the floor higher, making a shallower, less protective cockpit. Almost always, the floor is only inches above the waterline, and this means we cannot have several generous scuppers at the sides of the cockpit, port and starboard, out of which green water could flow quickly. If we had them, a slight overload or change in hull attitude on rough water would put some of them under and sea water would pour in. It is necessary to settle for a smaller stern drain, out of which water flows with agonizing slowness.

It thus works out to be a matter of each craft in this size range being an individual case. The Ski Barge type of boat popular inland is rather light and wide, and so it draws little water. Its floorboard can be set only inches above the hull bottom and still have enough volume under it for adequate buoyancy in case of filling with water. Some boats have enough foam flotation in their sides so that, when filled with water, they will remain level and tend to rise, making water flow out of the transom drain and eventually they will bail themselves. Put a standard seven – eighths-inch transom drain plug into the outlet of a standard household heating oil tank, fill the tank with water, and settle into a comfortable armchair to record the time it takes for that volume of “cockpit water” to drain out!

In the case of the new fishing boats under discussion, they are comparatively big, buoyant craft that normally carry a light passenger load. They don’t settle too much when a normal load goes aboard. With their big gas tanks amidships, they tend to settle level instead of by the stern when topped up. Their hulls tend to be reasonably high-sided as compensation for being entirely open, so floors can be set putting occupants so high in the cockpits as to make it easy to fall overboard. Most have cockpit rails that increase effective cockpit depth from the stand-point of falling overboard. I can’t say that all of them are completely self-bailing under all conditions, but as you shop around among them you can evaluate each with the knowledge you inhaled a few paragraphs back, and make your choice with your eyes open.

Most of these new boats have only an average amount of deadrise in their vee bottoms, some a little more than average, and only a few – mostly the aluminum ones—could qualify as deep-vee types. The reason is that, while deep-vee hulls are excellent for leaping from wave to wave at full throttle in deep sea ocean races, their shape naturally makes them more prone to roll when at rest or moving slowly. This does not make for a happy fishing platform. This is not the case with certain modified vee hulls designed to combat this problem. Also, any boat with a deep vee hull will draw more water at low speed, a matter of no consequence to ocean racers, but often a decided shortcoming for fishing where shallow waters are to be negotiated. Also, it takes high power to boost a deep-vee hull onto plane and fishermen tend to be happy with medium power.

A feature so common as to be practically standard is one form or another of “double hull” construction. A separate fiberglass molding forming the inside of the cockpit is set down into the hull molding. Often air spaces or foam material goes between these outer and inner shells, distributed as necessary for upright flotation when awash. A large open fiberglass hull tends to be a pretty rubbery thing when it comes out of a mold, and these inner shells are a good way to stiffen them up while at the same time providing an attractive and very, very easily cleaned interior – a matter of top importance to fishermen.

On looking at the various popular makes, one is struck by the number of well-thought-out details they have for the convenience of the fisherman. Aboard the Mako boats I noticed night lights set into the sides of the control console, where they can cast a soft glow into the cockpit without shining into the eyes of the occupants or being visible (and confusing) to other boats. Wooden rod holders – the usual boards with sawn slots to receive rods – are mounted on hinges so they can be folded against the cockpit side when not in use. Foot steps are molded into the cockpit liner, port and starboard, up forward to facilitate mounting to the short foredeck. The 17-footer offers a 30 gallon fuel tank as optional equipment, and the 22-footer has a 44 gallon tank as standard. Try fitting that capacity into some outboard boats!

On the SeaCraft, I noticed that the fuel tank quantity gauge is clearly visible to the driver. The folding top is white, but has a black liner on its under side which no doubt reduces sun glare in the eyes of people standing under it. In the stern drive version of this boat, the driver’s seat is formed by a storage box, and this box slides fore and aft on tracks to afford both a comfortable seating position, when the operator wishes to drive sitting down, and clear foot room when he wishes to stand up. This make has more vee in its bottom than some others, and the added volume created by deepening the hull enables the boat to float at such a level that self-bailing of the cockpit is feasible.

The Aquasport, too, has its attention-getting features. One I saw had twin gas tanks under its control console, and there’s nothing like twin tanks for keeping track of fuel supply. When the motor or motors quit from fuel starvation, you know definitely and positively that half of the supply has been used up, and you plan your return trip accordingly! The raised floorboard up forward puts one in a good position for casting, and a bow rail makes for adequate safety. Under this deck is a commodious storage space for equipment.

Each manufacturer offers an assortment of extra equipment, including various styles of folding tops which enable a boat of this type to be substantially closed in and covered over when one wishes to camp overnight or operate in miserable weather. Transoms are in most cases wide enough to accept two outboard motors; some of these boats go well out to sea, and the twins give better speed than a small auxiliary motor for getting home over a long distance in the event one fails. These boats are not exactly cheap, although it can truthfully be said that they cost a good deal less than some of the big boats that have been used to seek gamefish many miles offshore!

Beg a ride – or better still a fishing trip – in one of these boats this summer and see for yourself how well it serves the ardent fisherman. The type is well established, and you’re going to see it around for a long time to come. Its development was made possible by the size and versatility of today’s pleasure boat industry.