Marine plumbing refers to the systems and components responsible for the movement, storage, and management of water and other fluids on a boat or ship. This system includes water supply lines, pumps, valves, hoses, and tanks, which ensure the delivery of potable water, the removal of wastewater, and the efficient operation of onboard systems such as toilets, showers, and sinks. Marine plumbing must withstand the unique challenges of a marine environment, including exposure to saltwater, constant motion, and potential corrosion. Therefore, materials used in marine plumbing, such as marine-grade stainless steel, corrosion-resistant plastics, and flexible hoses, are chosen for their durability and ability to perform reliably under these conditions.

Proper maintenance and installation are crucial to the effectiveness and longevity of a marine plumbing system. Regular inspections are necessary to detect leaks, blockages, or signs of wear that could lead to system failure. In addition, ensuring that the plumbing system is designed with appropriate ventilation, backflow prevention, and waste management components is essential for both environmental protection and the safety of the vessel’s occupants. Given the confined spaces on many boats, marine plumbing systems are often compact and require careful planning to optimize space while maintaining functionality and ease of access for repairs and maintenance.

THERE CAN BE a whole range of plumbing inside a modern boat:

- from the engine cooling system (see Engines and Their Systems“Determining the Condition of the Engines and Their Systems”), to domestic fresh water and toilet supplies;

- flushing, fire-fighting and bilge pumping systems;

- drains;

- and anchor wash,

so that if you dig around under the floors and in the bilges you’re likely to find pipes of every description. Smaller and older boats may not be so well endowed, but you’ll still perhaps see pipes for a cold water supply and bilge pumps tucked away, mostly out of sight and possibly out of mind. Even the smallest boat should have pipework for a bilge pump at the very least.

It can add up to a lot of pipework, and leaks or failures could lead to water in the bilges, corrosion of fittings and, in a worst-case scenario, the boat sinking. So, the first thing you need to do when surveying a boat’s plumbing is to differentiate between those parts of the system that are critical to safety, which obviously need a very careful check, and those which will lead to mere inconvenience or nasty smells if something goes wrong.

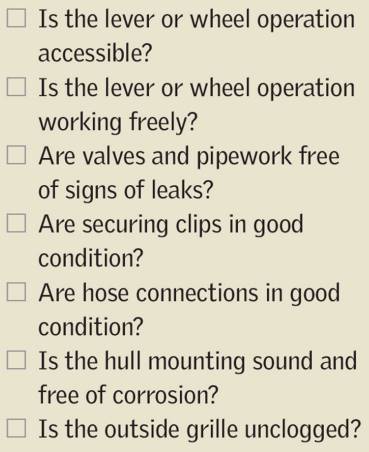

Some systems are connected to the outside sea by means of through-hull fittings, and these are perhaps the most critical to check during any survey; just because a hull fitting is above the waterline when the boat is at rest, it doesn’t mean the hull is immune from flooding if there is a failure here.

Ideally, you’d want to check the entire plumbing system, but you may struggle to access many parts of the system without serious dismantling since it is usually installed before the deck or inner mouldings. Even critical fittings such as the seacocks, which you may need to find and operate in a hurry if a pipe or joint fails at sea, can be hidden from view.

Add incoming water and a submerged seacock and you can see how panic might set in quickly! Therefore if you can, try to get hold of the plumbing system for the boat, which makes it easier to trace the various pipes. If you’re surveying your own boat, label the pipes as you discover what they do and where they lead.

Fresh water systems

THE FRESH WATER system usually comprises a tank, a pump and the piping to the taps/showers. On more sophisticated installations you may also find a separate hot Complete Guide to Below Deck Sailboat Systems: Ventilation, Marine Heads, Water Systems and morewater system connected to the engine via a heat exchanger or calorifier, in which engine heat is used to heat the domestic water. Alternatively an electric immersion heater may be present or, more rarely, a diesel-fired heater.

Modern yachts have quite sophisticated systems for supplying all the bathrooms and the galley, while on older boats there may be just one or two outlets in the galley and the toilet compartment. The pump that circulates the water may be hand or electrically operated and here all you can do is a visual check for corrosion, although you may be able to test that the pump is working.

The best material for pipework is PVC because not only does it stand up well to vibration, it is easy to install and does not corrode. The same copper found in land systems is sometimes used, which isn’t ideal because it doesn’t stand up well to vibrations. Polyurethane flexible piping is the easiest to install, but this can harden over time and may crack with age.

Any problems are likely to be found in the pipework, so check that it is adequately secured in place (unsecured pipes could cause trouble when the boat is at sea) and free of leaks (in copper piping, leaks show in the tell-tale green signs of corrosion). Also check that the tank, which can be quite a weight, is securely fastened if it is a stand-alone unit. Any signs of movement will be evident in chafe or wear at the same securing points as the fuel tank (see Engines and Their Systems“Determining the Condition of the Engines and Their Systems”).

The fresh water system pumps water into a sink, wash basin or the shower tray, but it of course has to drain away after use. Water may drain into a grey water tank and then be pumped overboard or there may be a direct drain. The pipework for such a drainage system is not particularly critical except of course that the pipe eventually connects with an overboard drain, meaning it can be open to the sea. Therefore it should meet the highest standards and be secured with clips on the flexible sections and the outlet fitted with a seacock (many boats don’t have the seacock on the basis that it is only a drain, but that is a false economy if the internal pipe gives way).

Toilet systems

THE TOILET SYSTEM is much more critical both as far as the safety of the boat is concerned and your comfort on board. However, it is yet another difficult system to examine in detail: today’s modern systems are usually supplied as a complete system to ensure reliability, but on older toilets you’ll usually need to poke around behind or below the toilet to get access to the pipework. For a full check it would probably be necessary to remove the toilet completely.

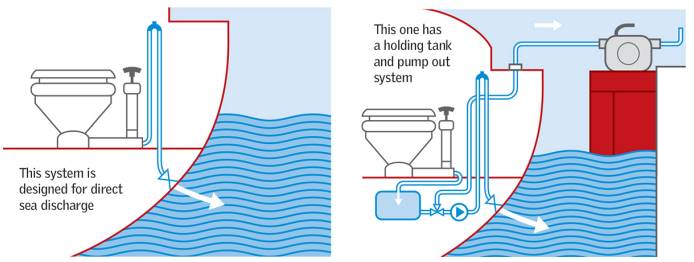

Systems can vary considerably in terms of installation and sophistication, with the old – and basic – system being a toilet bowl with a pump that sucks water in from outside before the mix in the bowl is pumped out overboard. These toilets are usually installed at or below the waterline, so the integrity of the water systems is vital since a failure can let water into the boat.

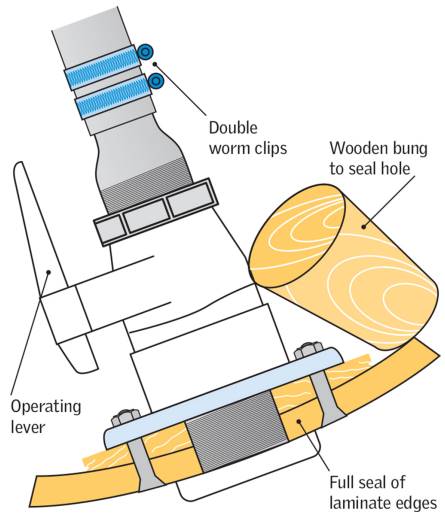

The inlet pipe – a small diameter flexible pipe connecting a seacock to the toilet pump – is usually fitted at a lower level than the exit pipe. The exit pipe is larger in diameter to allow solids to pass through, and the usual exit for this pipe is just below the waterline when the boat is upright. Again, a seacock is fitted at the outlet. We will take a closer look at seacocks later in the chapter, but for now check that high quality piping is used for the whole installation and it is secured at each connection by double worm drive hose clips (it may be good practice to close these toilet seacocks when at sea, since there are higher stresses on the pipework when the boat is pounding into waves, but then, of course, the toilet is out of action).

The type of flexible piping used is also important and at the very least this should be wire reinforced plastic, and the plastic should be of a grade that does not harden with age, which would create the possibility of cracking. If you’re surveying your own boat, it would be worth replacing the hose, say, every five years.

These days you are only allowed a direct discharge of sewerage into the water when well out at sea and most modern systems and many older ones have had to be upgraded to a system that features a holding tank. Such a tank allows for the sewerage to be held on board when in the marina or in harbour, before it can be pumped out at sea or at one of the dedicated pump-out stations now found in most marinas. Such a system is more complex and involves having a pump and/ or macerator in the system to break up the solids when pumping out. These holding tank systems generally use rigid PVC piping for the outflow from the toilet to the tank, and here again you’re looking for any signs of leaks. The pipe from the pump to the overboard outlet is likely to be flexible and is first routed upwards before turning downwards to the skin fitted with a suction break valve at the top, which prevents water siphoning back into the tank from outside. Many modern boats have electric or vacuum toilets that are designed to use the minimum amount of water, so that the black water holding tank does not fill up rapidly. They usually use fresh water, so at least here you only have one through-hull fitting to examine. Any problems in the toilet system can usually be detected initially by the smell, but don’t wait for that before doing your checks.

Drainage systems

THE DRAINS THAT take water from spray, rain or washing down overboard will also have an overboard discharge, and this should have a seacock fitted. furthermore, many modern boats do not allow any through-hull fittings in the topsides so they have to exit underwater. The most obvious drains are those found in sailboat cockpits and these often have crossover piping so that water does not flow back up the pipe when the boat is heeled under sail. This means that the port drain will exit on the starboard side and vice versa. Again, because these drains are connected to the outside sea the piping needs to be reinforced and of the best quality, and of course a seacock is required.

Deck hatches giving access to the engine compartments, such as those in the cockpit of a motorboat, often have channels fitted outside the hatch seals so that any water collecting here can be drained away and does not find its way below. You may also find drains on the flybridge of a cruiser so that water is collected and drained away below the waterline, meaning it won’t stain the pristine topsides. These various drains are often channelled into one collector and, from there, a pipe leading first to a seacock and then overboard.

For preventing leaks below and sea water entering the hull, there is really no substitute for high quality in such drainage systems and on the final pipe overboard. All pipework should also be secured against movement in order to reduce the chance of the plastic sections of the pipework cracking with age. If you can, perform a water test which will indicate any leakage.

Anchor and deck wash systems

ANCHOR WASH SYSTEMS are a modern development designed to keep any mud that comes up on the anchor chain off the deck, so that the chain is washed clean in the anchor locker. Of course, such a system doesn’t stop some of the mud dropping off as it comes across the deck and into the capstan, but at least it does not wash down the deck. Anchor and deck wash systems can draw in sea water with a pump and distribute it where required. The wash system is essentially a nozzle (or nozzles) that squirts water onto the chain as it drops into the chain locker, so it is largely out of sight. Drains are fitted at the bottom of the locker, usually just above the waterline so that the water/mud mixture can drain away automatically. The whole system is designed to be automatic: just press a switch to start the pump and the water does the rest. A deck wash system works in a similar way and the two may even be combined with a valve to switch the water flow from one to the other.

Once again, here is a system that requires a high quality installation. First you have a suction inlet where the water is drawn in, so any failure here will allow water into the boat. Second, if the delivery hose is leaking, water is being pumped into the boat, possibly into places without an outlet. Once again it is a question of double worm drive clips on the hoses and high quality hoses to ensure reliability and security. You’ll also need to check the outlet drains at the bottom of the chain locker; they need to be clear and large enough to drain the debris coming off the chain. The switch that controls the anchor wash pump will often be found on the dashboard where it could get knocked on accidentally and if the drains are not clear, the chain locker can fill with water and the weight can force the boat to start going down by the head.

Bilge pumps

BILGE PUMPS ARE an essential part of the Equipment of a Sailboat: What You Need to Have on Board While Sailingboat’s equipment and you will usually find one in each compartment when the compartments are isolated and do not drain into a common sump aft or amidships. You can get both hand operated and electric bilge pumps, with the latter being an almost universal fit except on the smallest of boats. As they are designed for a one-way flow taking water out of the boat, there should not be any major problems here. However, bilge pumps tend to be out of sight, out of mind, so during a survey, try introducing some water into the bilges to check they are actually functioning. With the boat up on dry land you might want to check there’s nobody standing under the outlet before you do this!

Apart from the bilge pumps not working in their automatic mode the only other problem you might find with this system is that the hose on the discharge side is coming adrift or isn’t adequately secured, so that any water pumped from the bilge promptly returns there. This won’t be much help if one of the other pipes on board has failed during an emergency.

Electric bilge pumps are usually wired to the boat’s battery so that the connection bypasses the main battery switch in order to allow the pump to continue working when the boat is unattended. Therefore, check that this wiring and its connections are to the highest standards so that failure is not an option.

Hoses

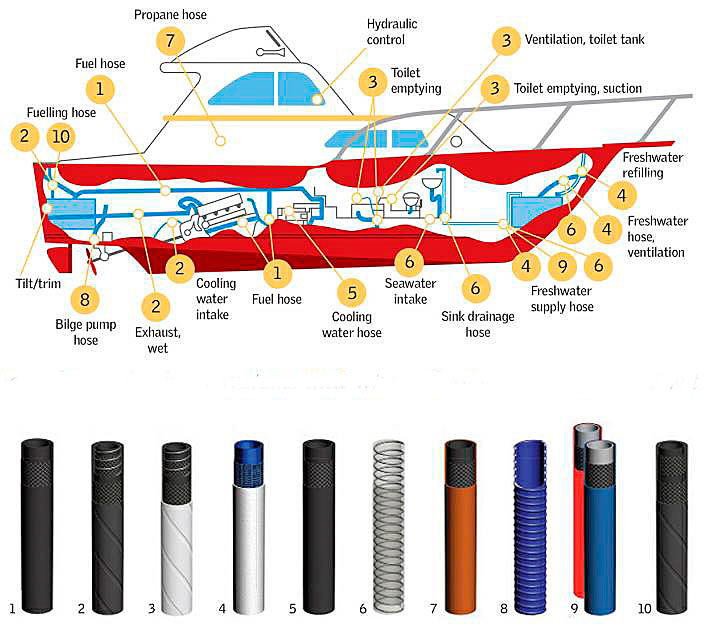

THE QUALITY OF the hoses used for the various systems on board is vital to ensure safety. You may find around ten different types of hose on board a boat, including the specialised types used for:

- fresh water;

- sanitation;

- propane;

- engine exhausts;

- pump suction;

- fuel;

- hydraulics;

- and engine cooling water.

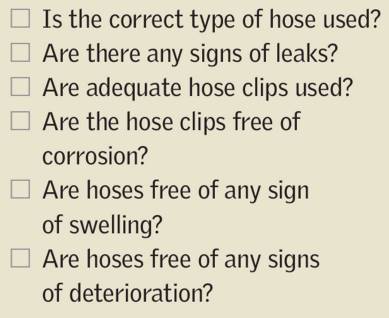

It is essential that when checking hoses you ensure they are of the right quality for the particular application. Of course, it’s not always easy to identify whether a hose is of the right type just by looking at it, but most hoses have some sort of reinforcement material incorporated into their makeup, usually a steel spiral, synthetic textile or combination of the two, and this may give you a clue about the quality.

The steel spirals are found on exhaust hoses, some fuel pipes and those required for sanitation and suction. The steel spiral will often be combined with a synthetic fabric reinforcement.

While you may not be able to assess the quality of hoses that are in place during the survey, at least you can ensure the correct type of hose is used when any replacement is carried out. You may see cheaper hose alternatives in use, but there is no substitute for good quality hose when you’re trying to avoid an unnecessary risk of failure. Check for corrosion, leaks and swelling and make a note to replace any that fall below the required quality.

Seacocks

NOW WE COME to the seacocks, which could be considered the safety net for all of these systems taking water from outside the hull into the boat or allowing water to drain overboard. There are a surprising number of these inlets on any boat, especially when you include the engine connections too, and most of these connections should incorporate a seacock so that the hole in the hull can be closed off if there is any problem with the internal system.

You will find that exceptions can be made on those pipes or systems in which the outlet is above the waterline, but if a boat is operating in rough seas or it is a sailboat that will heel over, those above-water outlets can find themselves submerged (the only pipe that doesn’t have a seacock fitted is the engine exhaust pipe).

Having a seacock fitted is one thing but that seacock won’t be much use if:

- a) it is not in working order;

- and b) it is not easily accessible.

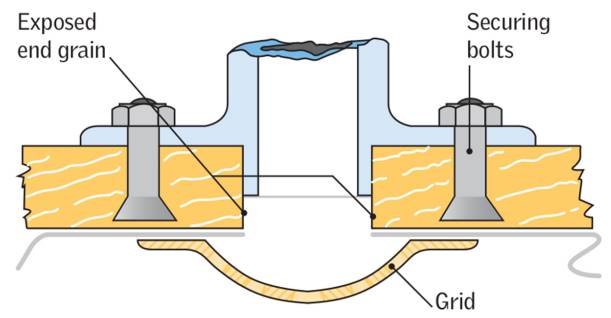

Good quality seacocks are made from non-corroding bronze and comprise a plate (the attachment point to the hull), the valve itself and its operating lever/handle, and a spigot (the attachment point for the hose). The attachment plate usually sits on the inside of the hull with the attachment bolts passing through the hull.

There may be a wooden pad between the seacock plate and the hull to help spread the local loading, while there should be a spigot that extends from the plate to the outside of the hull to help seal the cut edges of the hull laminate or planking. This is important, as it prevents water from entering the exposed internals of the laminate or wood, which could set off delamination or rot in the exposed sections.

A grille is usually fitted outside when the pipe is an inlet in order to reduce the chance of solid matter entering the seacock and blocking the pipe. On metal hulls the seacock may be bolted or even welded directly onto the metal plating. In aluminium hulls, stainless steel seacocks may be specified to reduce the chance of electrolytic corrosion.

Seacock Types

There are three main types of seacock:

- the gate valve;

- the ball valve and the tapered valve.

The gate valve makes its seal with a vertical plate that moves up and down inside the valve. It is controlled by a screw handle so it may require several turns to open and shut the valve.

On modern boats, it is the ball valve that is widely used and this requires just a quarter of a turn on the operating lever to open or close the valve, which makes operation quick and simplifies things in an emergency. Here there are seals inside the valve to ensure the whole thing is watertight when closed.

More likely to be found on older boats, the tapered valve is similar in its operating lever system, requiring just the quarter turn to operate it, but here the moveable part of the valve is a tapered cone that operates inside a matching tapered hole. The adjustment in the valve may require tightening to form the seal in the moveable tapered part. Tapered valves may require stripping down every so often in order to grease the moving and fixed parts and to reset the valve adjustment, or the adjustment may be spring loaded to draw the taper in tightly to its seating.

Seacock condition is a bit like a barometer for the condition of the rest of the boat, both in the original standard of construction and the level of maintenance that has taken place since the boat was new.

The seacock that doesn’t need maintenance has not yet been invented: all seacocks need regular maintenance, even if that only means opening and closing the valve a few times and perhaps lubricating it to ensure it works. It is quite easy to see whether a seacock has been operated in this way because the handle will be clean and shiny and there should be no signs of corrosion.

However, the chances are you’ll find the seacocks in a neglected condition during your inspection and in this case you’d need to examine them a lot more closely. It is not unusual to find evidence of corrosion on the outside, and if you struggle to operate the valve by hand, it will need stripping down to free things up. If you see salt crystals around the seacock, it is probably leaking. Any signs of neglect should raise alarm bells: chances are, if the valve hasn’t been properly maintained or operated regularly, the attached pipework and securing clips may have suffered from comparable neglect. Any through-hull seacock should have at least double worm drive clips securing the flexible pipe to it and any signs of swelling in the rubber or plastic at the attachment point should be a warning sign that replacement is required. Pipework should also be checked for surface cracking, which can indicate ageing. Again, you may find that the seacocks on the engine cooling water intakes show signs of having been maintained or at least operated, since they are reasonably accessible, but those tucked away in other less accessible parts of the boat may have been neglected.

Read also: Step-by-Step Guide to Choose the Boat for You

On above water outlets you will often find skin fittings made from plastic that simply have a contoured outside flange held tightly in place with a washer and nut in matching material on the inside. It’s a simple solution to providing a pipe outlet and it can work for bilge pump and similar outlets that are mounted well above the waterline. These Technical Advice on the Boat Inspection Process and Why Survey Your Own Boatskin fittings do not have a seacock incorporated into the system and they are simply a termination to the pipe. Plastic will generally harden after ten years or more, particularly where it is exposed to sunlight, so fittings of this type should be viewed with a degree of caution on older boats where they may have become brittle; if they have turned yellow, it might be a good idea to replace them. Plastic fittings of this type are not recommended at or below the waterline where every connection should have a metal seacock built in.

Because of their importance to the safety and security of the boat, you would think that seacocks would have been designed to be more accessible in case of emergency. Even the various authorities don’t seem to be concerned with accessibility, only requiring that seacocks are fitted to underwater inlets and outlets. Some form of external or extension means of operation would certainly help, since in the event of a failure of any of these systems, the operating lever of the seacock is likely to be the first thing that goes underwater.

Hello, How about TruDesign Seacock ball valves ?