Uncover the world of modern satellites in our in-depth article. Learn about the latest trends, technologies, and applications shaping the satellite industry. From satellite orbits and transmission bands to market opportunities and the future of fiber optic technology, explore how modern satellites are revolutionizing communication and connectivity.

- Background

- Industry Issues and Opportunities: Evolving Trends

- Issues and Opportunities

- Evolving Trends

- Basic Satellite Primer

- Satellite Orbits

- Satellite Transmission Bands

- Satellite Signal Regeneration

- Satellite Communication Transmission Chain

- Satellite Applications

- Satellite Market View

- Where is Fiber Optic Technology Going?

- Innovation Needed

Satellite services, spanning the commercial arena, the military arena, and the earth sensing arena (including weather tacking), offer critical global connectivity and observation capabilities, which are perceived to be indispensable in the modern world. Whether supporting mobility in the form of Internet access and real-time telemetry from airplanes or ships on oceanic routes, or distribution of high-quality entertainment video to dispersed areas in emerging markets without significant infrastructure, or emergency communications in adverse conditions or in remote areas, or earth mapping, or military theater applications with unmanned aerial vehicles, satellites fill a void that cannot be met by other forms of communication mechanisms, including fiber optic links.

Over 900 satellites were orbiting the earth as of press time. However, due to the continued rapid deployment of fiber and Internet Protocol (IP) services in major metropolitan areas where the paying customers are, including those in North America, Europe, Asia, South America, and even in Africa, tech-savvy and marketing-sophisticated approaches that organically integrate IP into the end-to-end solution are critically needed by the satellite operators to sustain growth.

Progressive satellite operators will undoubtedly opt to implement, at various degrees, some of the concepts presented here, concepts, frankly, not per se surprisingly novel or esoteric, since the idea of making satellites behave more than just microwave repeaters (microwave repeaters with operative functionally equivalent to the repeaters being deployed in the 1950s in the Bell System in the United States), in order to sustain market growth with vertically integrated user-impetrated applications, was already advocated by industry observers in the late 1970s and by the early industry savants.

Background

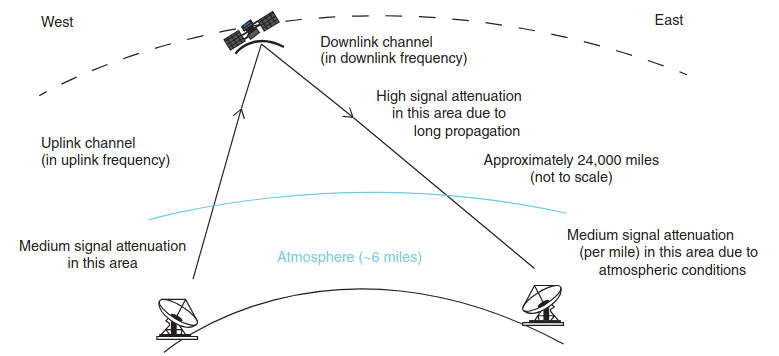

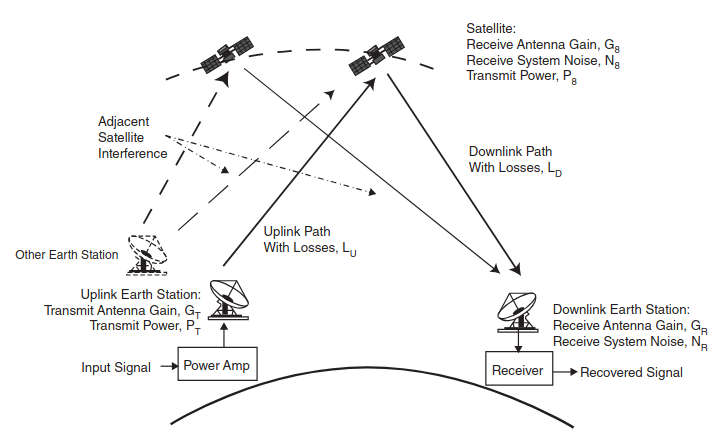

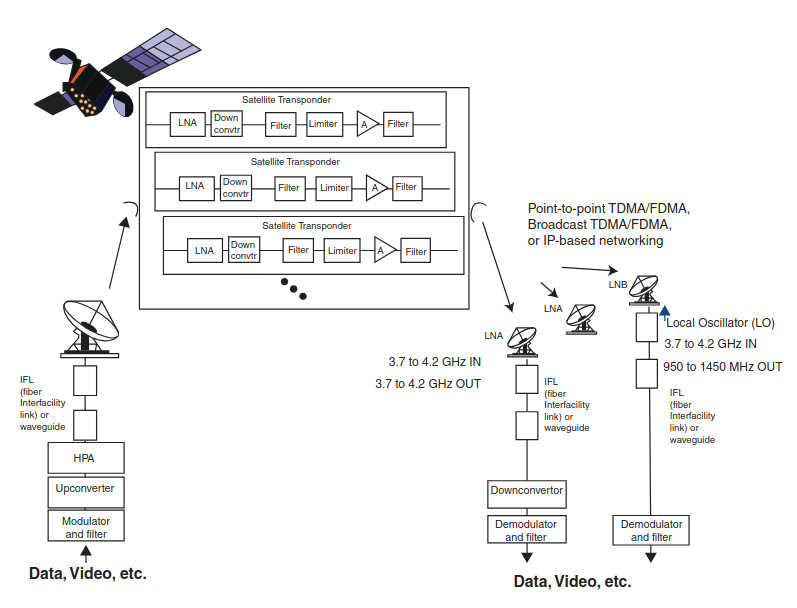

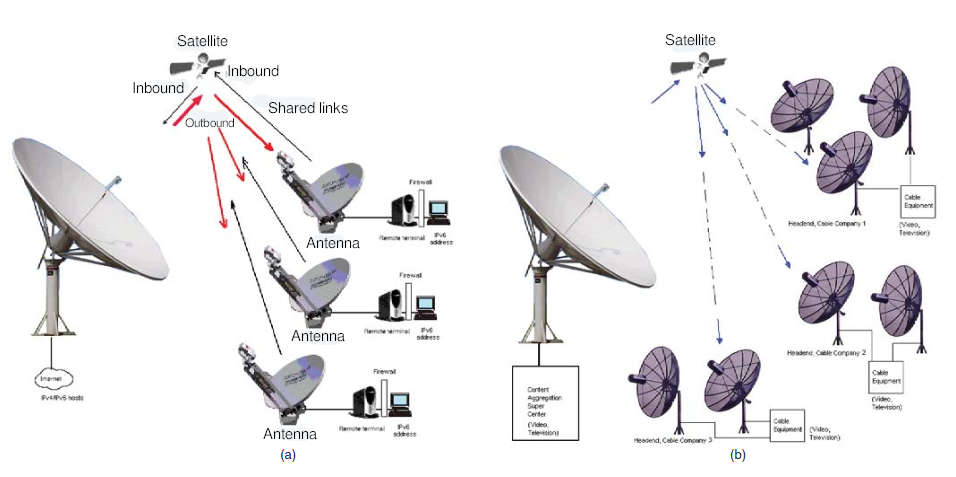

Satellite communication is based on a line-of-sight (LOS) one-way or two-way radio frequency (RF) transmission system that comprises a transmitting station utilizing an uplink channel, a space-borne satellite system acting as a signal regeneration node, and one or more receiving stations monitoring a downlink channel to receive information. In a two-way case, both endpoint stations have the transmitting and the receiving functionality (see Figure 1).

Satellites can reside in a number of near-earth orbits. The geostationary orbit (GSO) is a concentric circular orbit in the plane of the earth’s equator at 35 786 km (22 236 miles) of altitude from the earth’s surface (42 164 km from the earth’s center – the earth’s radius being 6 378 km). A geosynchronous (GEO) satellite In this category whenever we use the term satellite we mean a geostationary communications satellite, unless noted otherwise by the context.x circles the earth in the GSO at the earth’s rotational speed and in the same direction as the rotation.

When the satellite is in this equatorial plane it effectively appears to be permanently stationary when observed at the earth’s surface, so that an antenna pointed to it will not require tracking or (major) positional adjustments at periodic intervals of time In practice, the term geosynchronous and geostationary are used interchangeably. A GSO is a circular prograde orbit (prograde is an orbital motion in the same direction as the primary rotation) in the equatorial plane, with an orbital period equal to that of the earth.x. Other orbits are possible, such as the medium Earth orbit (MEO) and the low Earth orbit (LEO).

Traditionally, satellite services have been officially classified into the following

categories:

- Fixed Satellite Service (FSS): This is a satellite service between satellite terminals at specific fixed points using one or more satellites. Typically, FSS is used for the transmission of video, voice, and IP data over long distances from fixed sites. FSS makes use of geostationary satellites with fixed ground stations. Signals are transmitted from one point on the globe either to a single point (point-to-point) or from one transmitter to multiple receivers (point-to-multipoint). FSS may include satellite-to-satellite links (not commercially common) or feeder links for other satellite services such as the Mobile Satellite Service or the Broadcast Satellite Service.

- Broadcast Satellite Service (BSS): This is a satellite service that supports the transmission and reception via satellite of signals that are intended for direct reception by the general public. The best example is Direct Broadcast Service (DBS), which supports direct broadcast of TV and audio channels to homes or business directly from satellites at a defined frequency band. BSS/DBS makes use of geostationary satellites. Unlike FSS, which has both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint communications, BSS is only a point-to-multipoint service. Therefore, a smaller number of satellites are required to service a market.

- Mobile Satellite Service (MSS): This is a satellite service intended to provide wireless communication to any point on the globe. With the broad penetration of the cellular telephone, users have started to take for granted the ability to use the telephone anywhere in the world, including rural areas in developed countries. MSS is a satellite service that enhances this capability. For telephony applications, a specially configured handset is needed. MSS typically uses satellite systems in MEOs or LEOs.

- Maritime Mobile Satellite Service (MMSS): This is a satellite service between mobile satellite earth stations and one or more satellites.

- While not formally a service in the regulatory sense, one can add Global Positioning (Service/) System (GPS) to this list; this service uses an array of satellites to provide global positioning information to properly equipped terminals.

A number of technical and service advances affecting commercial satellite communications have been seen in the past few years; these advances are the focus of this textbook. Spectral efficiencies are being vigorously sought by end-users in order to sustain the business case for content distribution as well as interactive voice (VoIP) and Internet traffic. At the same time, to sustain sales growth, operators need to focus on delivering IP services (enterprise and Internet access), on next-generation video (hybrid distribution, caching, nonlinear/time shifting, higher resolution), and on mobility.

Some of the recent technical/service advances include the following:

- Business factors impacting the industry at press time included the desire for higher overall satellite channel and system throughput. Improved modulation schemes allow users to increase channel throughput: advanced modulation and coding (modcod) techniques being introduced as standardized solutions embedded in next-generation modems provide more bits per second per unit of spectrum, and adaptive coding enables more efficient use of the higher frequency bands that are intrinsically susceptible to rain fade; extensions to the well-established baseline DVB-S2 standard are now being introduced.

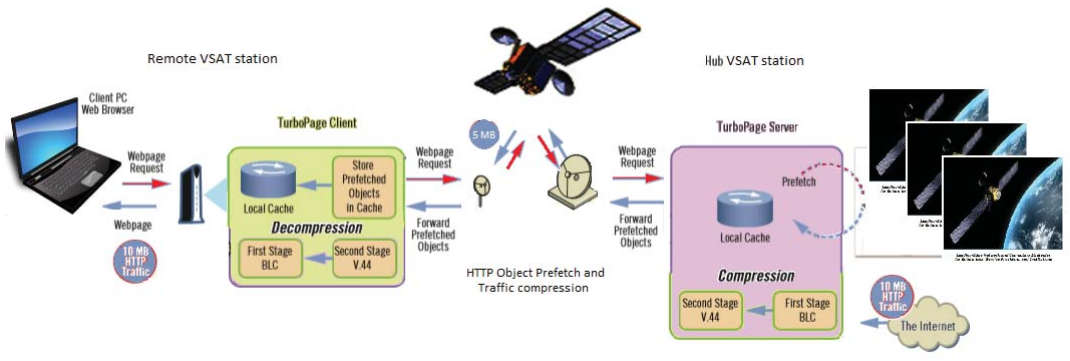

- High throughput is also achieved via the use of spotbeams on High Throughput Satellites (HTSs), typically (but not always) operating at Ka-band (18,3–20,2 GHz for downlink frequencies and 28,1–30 GHz for uplink frequencies), and via the reduction of transmission latency utilizing MEO satellites. HTSs are capable of supporting over 100 Gbps of raw aggregate capacity and, thus, significantly reducing the overall per-bit costs by using high-power, focused spot beams. HTS systems and capabilities can be leveraged by service providers to extend the portfolio of satcom service offerings. HTSs differ from traditional satellites in a number of ways, including the utilization of high-capacity beams/transponders of 100 MHz or more; the use of gateway earth stations supporting one or two dozen beams (typically with 5 Gbps capacity requirement); high per-station throughputs for all the remote stations; and advanced techniques to address rain attenuation, especially for Ka-band systems.

- Providing connectivity services to people on-the-move, for example, for people traveling on ships or airplanes, where terrestrial connectivity is lacking, is now both technically feasible and financially advantageous to the service providers. When that is desired on fast-flying planes, special antenna design considerations (e. g., tracking antennas) have to be taken into account.

- M2M (machine-to-machine) connectivity, whether for trucks on transcontinental trips, or aircraft real-time-telemetry aggregation, or mercantile ship data tracking, opens up new opportunities to extend the Internet of Things (IoT) to broadly distributed entities, particularly in oceanic environments. With the increase in global commerce, some see increasing demands on maritime communication networks supported by satellite connectivity; sea-going communications requirements can vary by the type of vessel, type of operating company, data volumes, crew and passenger needs, and application (including the GMDSS [Global Maritime Distress and Safety System]), so that a number of solutions may be required or applicable.

- Emerging Ultra High Definition Television (UHDTV) (also known as Ultra HD or UHD) provides video quality that is equivalent to 8-to-16 HDTV screens; clearly, this requires a lot more bandwidth per channel than currently used in video transmission. So-called 4 K and 8 K versions are emerging, based on the vertical resolution of the video. Satellite operators are planning to position themselves in this market segment, with generally-available broadcast services planned for 2020, and more targeted transmission starting as of press time. UHDTV will require a bandwidth of approximately 60 Mbps for distribution services and 100 Mbps for contribution services. The use of DVB-S2 extensions (and possibly wider transponders, e. g., 72 MHz) will be a general requirement. The newly emerging H.265/HEVC (High Efficiency Video Coding) video compression standard (algorithm) provides up to 2x better compression efficiency compared with that of the baseline H.264/AVC (Advanced Video Coding) algorithm; however, it also has increased computational complexity requiring more advanced chip sets. Many demonstrations and simulations were developed in recent years, especially in 2013, and commercial-grade products were expected in the 2014–2015 time frame, just in time for Ultra HD applications (both terrestrial and satellite based). Even in the context of Standard Definition (SD)/High Definition (HD) video, upgrading ground encoding equipment by content providers to H.264 HEVC reduces the bandwidth requirements (and, hence, recurring expenditures) by up to 50 %. Upgrading from DVB-S2 to DVB-S2 extensions (DVB-S2X) can reduce bandwidth by an additional 10–60 %.

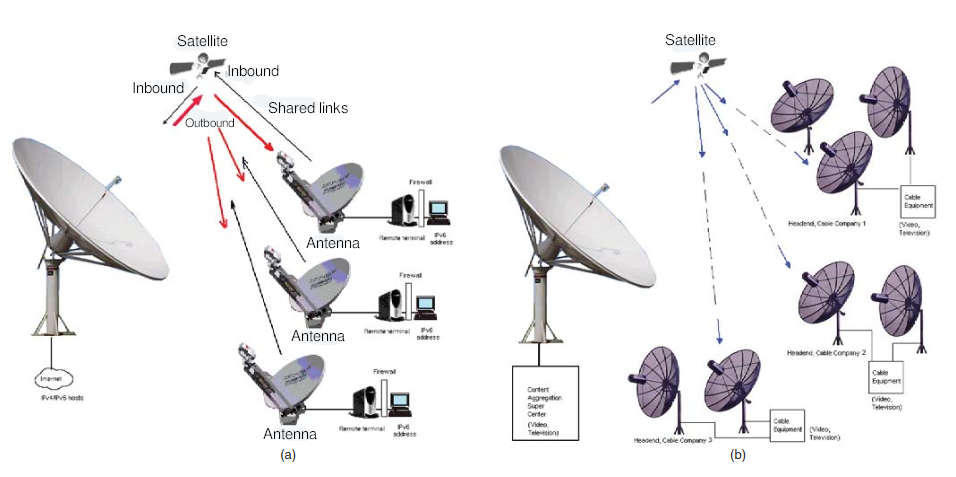

- Hybrid networks combining satellite and terrestrial (especially IP) connectivity have an important role to play in the near future. The widespread introduction of IP-based services, including IP-based television (IPTV) and over-the-top (OTT) video, driven by continued deployment of fiber connectivity, will ultimately reshape the industry. In particular, IP version 6 (IPv6) is a technology now being deployed in various parts of the world that will allow true explicit end-to-end device addressability. The integration of satellite communication and IPv6 capabilities promises to provide a networking hybrid infrastructure that can serve the evolving needs of government, military, IPTV, and mobile video stakeholders, to name just a few.

- At the core technology level, electric (instead of chemical) propulsion is being investigated and, in fact, being deployed; such propulsion approaches can reduce spacecraft weight (and so launch cost) and possibly extend the spacecraft life. According to proponents, the use of electric propulsion for satellite station-keeping has already changed the global satellite industry, and now, with orbit-topping and orbit-raising, it is poised to transform it.

- In addition, new launch platforms are being brought to the market, again with the goal of lowering launch cost via increased competition.

It is thus self-evident that satellite communications play and will continue to play a key role in commercial, TV/media, government, and military communications because of its intrinsic multicast/broadcast capabilities, mobility aspects, global reach, reliability, and ability to quickly support connectivity in open-space and/or hostile environments. This text surveys some of these new key advances and what the implications and/or opportunities for end-users and service providers might be. The text is intended to be generally self-contained; hence, some background technical material is included in this article.

Industry Issues and Opportunities: Evolving Trends

Issues and Opportunities

Expanding on the observations made in the introductory section, it is instructive to assess some of the general industry trends as of the mid-decade, 2010s. Observations such as these partially characterize the environment and the trends:

“ … a change of the economics of the industry [is] key to the satellite sector’s long-term growth … We have to be more relevant, more efficient, we have to push the boundaries … the industry needs to both drive down costs and expand the market through innovation … ”.

“ … the satellite market is seeing dramatic change from the launch of new high-throughput satellites, to the dramatic drop in launch costs brought on by gutsy new entrants … more affordable and reliable launch options [are becoming available] … ”.

“ … it is an open question as to who will see the fastest rate of growth. Will the top four continue to score the big deals and push further consolidation, or will the pendulum swing to the regional players with their closer relationships to the domestic/national client bases and launch of new “national flag” satellites? … ”.

“ … to combine with its wireless, phone and high-speed broadband Internet services as competition ramps up; the pool of pay-TV customers is peaking in the US [and in Europe] because viewers are increasingly watching video online … ”.

“ … The TV and video market is experiencing a dramatic shift in the way content is accessed and consumed, that should see no turning back. Technical innovation and the packaging of new services multiply the … interactions between content and viewers … Four major drivers are impacting the way content is managed from its production to its distribution and monetization.

They are:

- Delinearization of content consumption, and multiplication of screens and networks to access content;

- Faster increase in competition than in overall revenues; new sources of content, intermediaries and distributors challenge the value chain;

- Shorter innovation and investment cycles to meet customer expectations, and;

- Fast growth in emerging regions opening new growth opportunities at the expense of an increasing customization to local needs … ”.

“ … seeking innovative satellite and launcher configurations is an absolute must for the satellite industry if it expects to remain competitive against terrestrial technologies … the cost of the satellite plus the cost of the launcher will … deliver a 36-megahertz-equivalent transponder into orbit for $1,75 million … ”.

“ … Many factors can disrupt the market and have an impact on competition, demand, or pricing … FSS cannibalization of MSS, emergence of new competitors in the earth observation arena, changes to the US Government’s behavior as a customer, growing competition from emerging markets, growth of government (globally) as a source for satellite financing, and adoption of a 4 K standard for DBS … ”.

“Innovation and satellite manufacturing are not always words that end up in the same sentence … Due to the expensive nature, risk aversion and technical complexity, innovation has been fairly slow in satellite communications … ”.

“ … After the immediate, high-return investments have been done, new growth initiatives are either higher risk or lower return … Is industry maturity itself a disruptor, forcing experiments that fall beyond the risk frontier? … ”.

“Higher speeds, more efficient satellite communication technology and wider transponders are required to support the exchange of large and increasing volumes in data, video and voice over satellite. Moreover, end-users expect to receive connectivity anywhere anytime they travel, live or work. The biggest demand for the extensions to the DVB-S2 standard comes from video contribution and high-speed IP services, as these services are affected the most by the increased data rates … ”.

“The latest market figures confirm that broadband satellites or so-called high-throughput satellite systems are on the rise. As the total cumulative capital expenditures in high-throughput satellites climbs to $12 billion, an important question must be raised: How will these new systems impact the mindset of our industry? … The large influx of this capacity to the market has created some concerns about the risk of oversupply in regions such as Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, and Asia Pacific … ”.

“ … [high-throughput satellite] are designed to transform the economics and quality of service for satellite broadband … satellites can serve the accelerating growth in bandwidth demand for multimedia Internet access over the next decade … Current satellite systems are not designed for the high bandwidth applications that people want, such as video, photo sharing, VoIP, and peer-to-peer networking. The solution is to increase the capacity and speed of the satellite. Improving satellite service is not just about faster speeds, but about increasing the bandwidth capacity available to each customer on the network to reduce network contention … ”.

“Procurement of commercial GEO communications satellites will remain stable over the next 10 years. While the industry will experience a short term decline from a high in 2013 … it will remain driven by replacements and some extensions primarily in Ku-band and HTS. However, a number of trends will affect the growth curve and considerably change the trade-off environment for satellite manufacturing:

- New propulsion types increasingly used;

- More platforms proposed by an increasing number of suppliers;

- Multi-beam architectures becoming more frequent;

- Launch services capabilities evolve toward higher masses.

The whole industry is shaping-up; including both satellite manufacturers and launch services providers … Market shares evolved significantly in the last few years and after years of complacency, certain players were bordering on insignificance in this important space … ”.

“ … We live in a smart, connected world. The number of things connected to the Internet now exceeds the total number of humans on the planet, and we’re accelerating to as many as 50 billion connected devices by the end of the decade … the implications of this emerging “Internet of Things (IoT)” are huge. According to a recent McKinsey Global Institute report, the IoT has the potential to unleash as much as $6,2 trillion in new global economic value annually by 2025. The firm also projects that 80 to 100 percent of all manufacturers will be using IoT applications by then, leading to potential economic impact of as much as $2,3 trillion for the global manufacturing industry alone … ”.

“ … The report has the following key findings:

- The wireless M2M market will account for nearly $196 Billion in annual revenue by the end of 2020, following a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 21 % during the six year period between 2014 and 2020;

- The installed base of M2M connections (wireless and wireline) will grow at a CAGR of 25% between 2014 and 2020, eventually accounting for nearly 9 Billion connections worldwide;

- The growing presence of wireless M2M solutions within the sensitive critical infrastructure industry is having a profound impact on M2M network security solutions, a market estimated to reach nearly $1,5 Billion in annual spending by the end of 2020;

- Driven by demands for device management, cloud based data analytics and diagnostic tools, M2M/IoT platforms (including Connected Device Platforms [CDP], Application Enablement Platforms [AEP], and Application Development Platforms [ADP]) are expected to account for $11 Billion in annual spending by the end of 2020 … ;”.

Kevin Ashton known for coining the term “The Internet of Things” to describe a system where the Internet is connected to the physical world via ubiquitous sensors, recently made these very cogent observations, which given the depth are quoted here (nearly) in full:

“Yesterday [April 27, 2014], the aerial search for floating debris from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 was called off, and an underwater search based on possible locator beacon signals was completed without success … The more than 50-day operation, which the Australian prime minister, Tony Abbott, calls “probably the most difficult search in human history,” highlights a big technology gap. We live in the age of what I once called “the Internet of Things,” where everything from cars to bathroom scales to Crock-Pots can be connected to the Internet, but somehow, airplane data systems are barely connected to anything … the plane’s Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS), which was invented in the 1970s and is based on telex, an almost century-old ancestor of text messaging made essentially obsolete by fax machines … When so much is connected to the Internet, why is the aerospace industry using technology that predates fax machines to look for flash drives in the sea?

Because, while technology for communicating from the ground has advanced rapidly in the last 40 years, technology for communicating from the sky has been stuck in the 1970s. The problem starts not with planes, but with the satellites that track them. The Sentinel-1A satellite, for example, weighs two and a half tons, costs around $400 million, and was launched on a rocket designed in Soviet Russia in the 1960s. The Sentinel can store the same amount of data as seven iPhones. When was this relic from the age of mainframe computers sent into orbit? On April 3. Huge, expensive, rocket-launched satellites with little computing power may make sense for broadcasting, where one satellite sends one signal to lots of things (such as television sets) but they are generally too expensive and not intelligent enough to be part of the Internet, where lots of things (such as airplanes) would send lots of signals to one satellite. This is why most satellites reflect TV signals, take pictures of the earth, or send the signals that drive GPS systems. It is also the reason airplanes can’t stream flight and location data like they stream vapor trails: cellphone and Wi-Fi signals don’t reach the ground from 30 000 feet, so airplanes need to be able to send information to satellites — satellites that, as well as being unable to handle network data economically, are designed to talk to rotating, dish-shaped antennas that would be impossible to retrofit to airplanes.

The solution to these problems is simple: We need new satellite technology. And it’s arriving. Wealthy private investors and brilliant young engineers are dragging satellites into the 21st century with inventions including “flocks” of “nanosatellites” that weigh as little as three pounds; flat, thin antennas built from advanced substances called “metamaterials”; and “beamforming,” which steers radio signals using software. On January 9, 2014a San Francisco-based start-up called Planet Labs sent a flock of 28 nanosatellites into space. The first application for this type of technology is taking pictures of the Earth, but it could also be used to receive data streaming from aircraft retrofitted with those new, flat “metamaterial” antennas. There are many other possible systems. Dozens of new satellite technologies are emerging, with countless ways to combine them. Streaming data from planes is about to become cheap and easy”.

Evolving Trends

The satellite Services, service options, and service providers change over time (new ones are added and existing ones may drop out as time goes by); as such, any service, service option, or service provider mentioned in this article is mentioned strictly as illustrative examples of possible examples of emerging technologies, trends, or approaches. As such, the mention is intended to provide pedagogical value. No recommendations are implicitly or explicitly implied by the mention of any vendor or any product (or lack thereof).x industry comprises spacecraft manufacturers, launch entities, satellite operators, and system equipment developers. Major operators include Eutelsat, Intelsat, SES, and Telesat; a cadre of national-based providers (particularly in the context of the BRICA countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and Africa) also exist. The industry’s combined revenue had a growth at around 3–4 % in 2013; emerging markets and emerging applications will be a driver for continued and/or improved growth: industry observers state that 80 % of future growth in satellite services demand will be in the southern hemisphere, although the “quality” of the revenues in those areas does not compare with that of the developed countries. Generally, operators worldwide launch about two dozen commercial communications satellites a year.

As hinted above, mobility for commercial users represents a major business opportunity for satellite operators. Some industry observers see a practical convergence of what were officially MSS and FSS. Many of the evolving mobility services are based on satellites supporting principally (or in part) FSS. Many airlines are planning to retrofit their airplanes to offer in-flight connectivity services. As an illustrative example, El Al Israel Airlines announced in 2014 that it was outfitting its Boeing 737 aircraft fleet to provide in-flight satellite broadband using ViaSat’s Exede in the Air service enabled by Eutelsat’s KA-SAT Ka-band satellite starting in 2015. (Eutelsat’s KA-SAT satellite covers almost all of Europe, the Middle East, parts of Russia, Central Asia, and the Eastern Atlantic.) Passengers will be offered several Internet service options, including one free service, to connect their laptops, tablets, or smartphones to the Internet; Exede in the Air is reportedly able to deliver 12 Mbps capacity to each passenger, a rate the company says is irrespective of the number of users on a given plane. To provide a complete in-flight Internet service to the aircraft, airline companies need to add airborne terminals, tracking antennas, and radomes to the aircraft, and also subscribe to satellite-provided channel bandwidth (air time) on selected satellites.

New architectures related to how satellites are designed are also emerging. It is true that until recently satellite operators have shown tepid interest for an all-electric propulsion satellite, principally because with this type of propulsion technology it takes months, rather than weeks, for a newly launched spacecraft to reach the final GSO operating position; satellite operators have indicated they are also concerned that, when they wish to move their in-orbit satellites from one slot to another during the satellite’s 15- to 20-year service lifecycle, such maneuvers will take much longer (these drifts are very common, enabling the operator to address bandwidth needs in various parts of the world, as these needs arise – in some cases up to 25 % of an operator’s fleet may be in some sort of drift state).

However, there are ostensibly certain economic advantages to electronic-propulsion spacecraft, which can bring transponder bandwidth costs down, thereby opening up new markets and applications. Some key operators have recently announced renewed interest in the technology. A large, complex spacecraft can weigh more than 6 000 kilograms; a reduction in weight will significantly reduce launch costs; electric propulsion can result in a spacecraft that weigh around 50 % of what it would weigh at launch with full chemical propellant. Some industry observers expect to see the emergence of a hybrid solution that saves some of the launch mass of a satellite through electric propulsion, but retains conventional chemical propellant to speed the arrival of the satellite to final operating position.

At the end-user level, there have been a number of technological developments, including the extensions for DVB-S2, tighter filter rolloffs in modems, adaptive pre-correction for transmission equipment nonlinearity as well as for group delay. These modem developments increase the bandwidth achievable in a channel (augmenting the application’s scope) or reduce the amount of analog spectrum needed to support a certain datarate (thus, reducing the cost of the application).

An area of possible new business and technical opportunities entails the “hosted payload” concept. NASA and the US Department of Defense (DoD) have begun to look at the commercial space sector for more cost-effective solutions compared with that of proprietary approaches, including the use of hosted payloads. Spacecraft constructed for commercial services can be designed for additional payload capacity in the area of mass, volume, and power. This capacity can be used to host additional (government) payloads, such as communications transponders, earth observation cameras, or technology demonstrations. These “hosted payloads” can provide government agencies with capabilities at a fraction of the cost of a dedicated satellite and also provide satellite operators with an additional source of revenue. A handful of GEO communications spacecraft launched in recent years incorporated hosted payloads, and there are indications that hosted payloads are gaining broader acceptance as government agencies are increasingly challenged to do more with reduced funding.

Recently the US Air Force’s Space and Missiles Systems Center (SMC) formed a Hosted Payload Office to better coordinate hosted payload opportunities across the government. The Air Force previously launched the Commercially Hosted InfraRed Payload (CHIRP) as a hosted payload on a communications satellite to test a new infrared sensor for use by future missile warning systems. The Air Force is reportedly planning to build on the success of CHIRP with a follow-on program called CHIRP+, again using hosted payloads to test infrared sensors. In another example, the Australian Defense Force placed a hosted payload on a commercial satellite, Intelsat 22, to provide UHF communications for military forces. The government reportedly saved over $150 million over alternative approaches, and the hosted payload approach was 50 % more effective economically than flying the payload as its own satellite, and it was 180 % more efficient than leasing the capacity. Some other examples of hosted applications include EMC-Arabsat and GeoMetWatch-Asiasat. The benefits of hosted payloads are measurable, although there may be institutional challenges for both satellite operators and potential government customers to work through the procurement and integration issues.

There is a new category of space technology developing called logistics in space. Services include life extension, tug, inclination removal, hosted payloads, and perhaps fuel transfer. ViviSat is an example of a company seeking to provide on-orbit servicing for GSO satellites.

Satellite-based M2M technology and services are receiving increased attention of late. As mentioned in the previous section, there is an urgent need, for example, to modernize the global airplane fleet to reliably support multifaceted, reliable, seamless tracking of aircraft function, status, and location. It would be expected that such basic safety features would be affirmatively mandated in the future by global aeronautical regulators (e. g., International Civil Aviation Organization [ICAO]). A satellite-based M2M antenna and modem cost around $125. While a terrestrial cellular system typically costs only $50, such a system does not have the full reach of a satellite-based solution, especially on a global scale. Work is underway to reduce the satellite-based system to $90.

Providers include Understanding Inmarsat SafetyNET: A Vital Tool for Maritime SafetyInmarsat, Iridium, Orbcomm, and Globalstar. The current satellite share of the global M2M market has been estimated at 5 % (each percentage point representing about 100 000 installed units); the expectation is for the growth in this segment in the near future. For example, satellite M2M messaging services provider Orbcomm launched a second-generation satellite constellation of 17 spacecraft on two Falcon 9 rockets operated by Space Exploration Technologies Corporation in 2014. The new-generation satellites will be backward compatible with existing Orbcomm modems and antennas, used to track the status of fixed and mobile assets, but the new satellites have six times more receivers on board than do the current spacecraft, and offer twice the message delivery speed (the second-generation constellation will have about 100 times the overall capacity of the existing satellites). Satellite M2M expands the connections enabled by terrestrial cellular networks not only domestically but also over land and sea.

Small special-purpose satellites (called smallsats and also called microsatellites or nanosatellites) are being assessed as an option by some operators. These satellites weigh in the range of 1–10 kg. Smallsats offer mission flexibility, lower costs, lower risk, faster time to orbit, and reduced operational and technical complexity. These satellites can be used for Geographic Information Systems, space science, satellite communication, satellite imagery, remote sensing, scientific research, and reconnaissance. Further along this continuum, one finds what are called picosatellites (e. g., CubeSats) that can perform a variety of scientific research and explore new technologies in space. Advances in all areas of smallsat technologies will enable such satellites to function within constellations or fractionated systems and to make cooperative measurements. Constellations of satellites enable whole new classes of missions for navigation, communications, remote sensing, and scientific research for both civilian and military purposes. The scope and affordability of such multispace-craft missions are closely tied to the capabilities, manufacturability, and technical readiness of their components, as well as the diverse launch opportunities available today. Earth observations and remote sensing are expected to account for largest market share by 2019; their use in commercial communication applications is also being investigated.

In 2014, Google announced plans to deploy 180 small LEO satellites to provide Internet access to underserved regions of the globe. Google had previously invested in the O3b Networks initiative, but apparently it has been looking for another entry mechanism into the satellite space. The project may require several billion dollars to complete. Google has been seeking ways to provide Internet access to developing regions without investing in expensive ground-based infrastructure; for example, they unveiled Project Loon to deliver Internet via solar-powered, remote-controlled air balloon. Details of the project were not generally available at press time, but the satellites under discussion may be of the smallsat type or just a notch above these.

New antenna designs are also emerging. For example, Panasonics uses a phased array antenna for in-flight Internet connectivity. As another example, in general, some MEO–HTS systems require two tracking antennas; however, some manufacturers (e. g., Kymeta) are developing a flat panel metamaterials antenna that is capable of tracking and instantaneously switching between satellites. As of press time Kymeta demonstrated the receive capability, and next the plan was to demonstrate a transmit capability. This antenna is currently Ka-band, but the vendor was reportedly planning a Ku-band version.

Some developers are assessing the opportunities of what has been called “cognitive satellite communication systems” (also known as “CoRaSat” [Cognitive Radio for Satellite Communications]). These systems are planned to have the ability to automatically detect and respond to impairments of the transmission channel, such as, but not limited to Adjacent Satellite Interference (ASI), Adjacent Channel Interference (ACI), rain fade, and terminal RF performance variations due to a number of causes. These advancements build on the more general concept of “cognitive radios”, where dynamic spectrum management is employed to deal with the scarcity of the overall transmission spectrum.

Since the allocated satellite spectrum is becoming scarce in various parts of the world due to growing demand for broadcast, multimedia, terrestrial mobility services, and interactive Internet services, applying efficient spectrum sharing techniques for enhancing spectral efficiency in satellite communication has become an important topic of late. Cognitive techniques such as Spectrum Sensing (SS), interference modeling, beamforming, interference alignment, and cognitive beamhopping are being assessed with the goal of possible implementation in the near future.

Satellite backhauling of regional 2G, 2.5G, 3G, and 4G/LTE services in under-developed areas (such as Africa and South America) is an emerging and evolving application. Satellite is also being utilized as the primary links in Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) core backbones and for restoration services where fiber and cable are used as the core. The goal is to enable MNOs mobile to reach more users while lowering overall cost to deliver these services. The addition of tower-based caching from satellite distribution can also support some video-on-demand services to smartphones in these regions of the world.

Another critical area for operators is the availability of spectrum; this relates to permits to transmit at specific frequency bands from specific orbital slots, as well as “landing rights,” which are provisions for authorizing the use of signals of foreign satellite services in specified countries. A key area of discussion at the 2015 World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC) is the wireless terrestrial operators effort to try to obtain C-band spectrum for evolving 4G/5G applications. Studies have shown that International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT) services interfere with fixed service satellites, which accounts for 38 % of the satellite mix (not counting HTS).

Satellite networks cannot continue to exist as stand-alone islands in a web of (required) anytime/anywhere/any media/any device connectivity. It follows that hybrid networks have an important role to play. The widespread introduction of IP-based services, including IP-based content distribution, will necessarily drive major changes in the industry during the next 10 years. The integration of satellite communication and IP capabilities (particularly IPv6) promises to provide a more symbiotic networking infrastructure that can better serve the evolving needs of the traveling public, the business enterprise, the government and military, and the IPTV/OTT/Content Delivery Network (CDN) players. Operators will need to become much more knowledgeable of IP to remain relevant.

At the business level, industry consolidation continues unabated. Two major consolidations in recent memory include AT&T’s purchase of DirectTV and Comcast purchase of Time Warner Cable. The claim is made that the acquiring companies were trying to get ahead of key business trends: rising content costs, the need for scale, the growing importance of broadband, and the growing use of video on mobile platforms were the driving forces behind these deals. While AT&T has focused on Internet services, they view “the future [as being] about delivering video at scale,” including satellite-based video and internet, all-of-the-above OTT video, and mobility.

The goals of these mergers relate to “synergies”: more efficiency in delivering services at a lower internal cost. In the United States, Comcast’s purchase of Time Warner Cable and AT&T’s purchase of DirectTV are seen as a “reordering of the video landscape that would seem to set both companies in motion toward more significant competition.” Other players have a need to reduce costs by re-engineering a number of functions, including nonrevenue producing ground assets, which are often excessively redundant in functionality and well beyond what would be needed to maintain business continuity. The expectation is that similar trends will affect other satellite/video operators worldwide in the next few years.

From a regulatory perspective, on May 13, 2014, the US State Department and the US Commerce Department published final rules transferring certain satellites and components from the US Munitions Import List (USMIL) to the Commerce Control List (CCL). These rules are the product of work between the Administration and Congress, in consultation with industry, to reform the regulations governing the export of satellites and related items. These changes will more appropriately calibrate controls to improve the competitiveness of American industry while ensuring that sensitive technology continues to be protected to preserve national security. The changes to the controls on radiation-hardened microelectronic microcircuits take effect 45 days after publication of the rule, while the remainder of the changes takes effect 180 days after publication. Earlier in the year, the Department of Justice published a Final Rule that revises the USMIL as part of the President’s Export Control Reform (ECR) Initiative. These changes remove defense articles that were on the USMIL but no longer warrant import control under the Arms Export Control Act, allowing enforcement agencies to focus their efforts where they are most needed. This important reform modernizes the USMIL and will promote greater security.

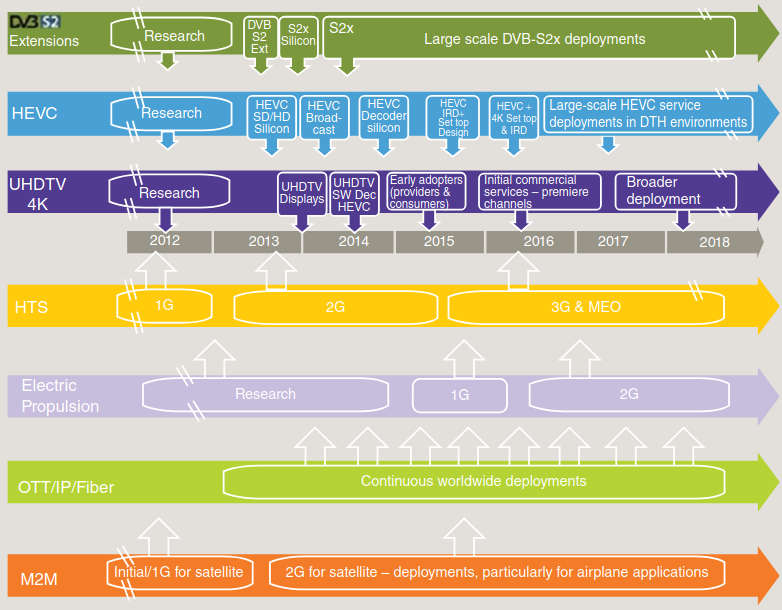

Figure 2 depicts a general timeline for some of the key advances impacting the industry.

Advances and innovation in satellite communications and satellite are not limited to the topics listed earlier, although these are the more visible initiatives at this juncture. The topics discussed in these introductory overview and trends sections will be assessed in greater details in the chapters that follow. The rest of this chapter provides a primer on satellite communications.

Basic Satellite Primer

This section covers some basic concepts in satellite communications; to make this treatise relatively self-contained.

Satellite Orbits

Communications satellites travel around the earth (“fly” in the jargon) in the well-defined orbits. Table 1 lists some key concepts related to orbits, expanding on the brief introduction to orbits provided earlier.

| Table 1. Key Concepts Related to Orbits | |

|---|---|

| Circular orbit | A satellite orbit where the distance between the center of mass of the satellite and of the earth is constant. |

| Clarke belt | The circular orbit (geostationary orbit) at approximately 35 786 km above the equator, where the satellites travel at the same speed as the earth’s rotation and thus appear to be stationary to an observer on earth (named after Arthur C. Clarke who was the first to describe the concept of geostationary communication satellites). |

| Collocated satellites | Two or more satellites occupying approximately the same geostationary orbital position such that the angular separation between them is effectively zero when viewed from the ground. To a small receiving antenna, the satellites appear to be exactly collocated; in reality, the satellites are kept several kilometers apart in space to avoid collisions. Different operating frequencies and/or polarizations are used. |

| Dawn-to-dusk orbit | A special sun-synchronous (SS) orbit where the satellite trails the earth’s shadow. Because the satellite never moves into this shadow, the sun’s light is always on it. These satellites can, therefore, rely mostly on solar power and not on batteries; they are useful for agriculture, oceanography, forestry, hydrology, geology, cartography, and meteorology. |

| Geostationary orbit (GSO) | Geostationary orbits are circular orbits that are orientated in the plane of the earth’s equator. A geostationary satellite completes one orbit revolution around the earth every 24 h; hence, given that the satellite spacecraft is rotating at the same angular velocity as the earth, it overflies the same point on the globe on a permanent basis (unless the satellite is repositioned by the operator). In a geostationary orbit, the satellite appears stationary, that is, in a fixed position, to an observer on the ground. The maximum footprint (service area) of a geostationary satellite covers almost one-third of the earth’s surface; in practice, however, except for the oceanic satellites, most satellites have a footprint optimized for a continent and/or a portion of a continent (e. g., North America or even continental Unites States). |

| Geostationary satellite | A satellite orbiting the earth at such speed that it permanently appears to remain stationary with respect to the earth’s surface. |

| Highly elliptical orbits (HEO) | HEOs typically have a perigee (point in each orbit that is closest to the earth) at about 500 km above the surface of the earth and an apogee (the point in its orbit that is farthest from the earth) as high as 50 000 km. The orbits are inclined at 63,4° in order to provide communications services to locations at high northern latitudes. Orbit period varies from 8 to 24 h. Owing to the high eccentricity of the orbit, a satellite spends about two-thirds of the orbital period near apogee, and during that time it appears to be almost stationary for an observer on the earth (this is referred to as apogee dwell). A well-designed HEO system places each apogee to correspond to a service area of interest. After the apogee period of orbit, a switchover needs to occur to another satellite in the same orbit in order to avoid loss of communications. Due to the relatively large movement of a satellite in HEO with respect to an observer on the earth, satellite systems using this type of orbit need to be able to cope with Doppler shifts. An example of HEO system is the Russian Molnya system; it employs three satellites in three 12-h orbits separated by 120° around the earth, with apogee distance at 39 354 km and perigee at 1 000 km. |

| Inclination | The angle between the plane of the orbit of a satellite and the earth’s equatorial plane. An orbit of a perfectly geostationary satellite has an inclination of 0. |

| Inclined orbit | An orbit that approximates the geostationary orbit but whose plane is tilted slightly with respect to the equatorial plane. The satellite appears to move about its nominal position in a daily “figure-of-eight” motion when viewed from the ground. Spacecrafts (satellites) are often allowed to drift into an inclined orbit near the end of their nominal lifetime in order to conserve onboard fuel, which would otherwise be used to correct this natural drift caused by the gravitational pull of the sun and moon. North–south maneuvers are not conducted, allowing the orbit to become highly inclined. |

| Low earth orbit (LEO) | LEOs are either elliptical or (more commonly) circular orbits that are at a height of 2 000 km or less above the surface of the earth. The orbit period at these altitudes varies between 90 min and 2 h and the maximum time during which a satellite in LEO orbit is above the local horizon for an observer on the earth is up to 20 min. With LEOs there are long periods during which a given satellite is out of view of a particular ground station; this may be acceptable for some applications, for example, for earth monitoring. Coverage can be extended by deploying more than one satellite and using multiple orbital planes. A complete global coverage system using LEOs requires a large number of satellites (40–80) in multiple orbital planes and in various inclined orbits. Most small LEO systems employ polar or near-polar orbits. Due to the relatively large movement of a satellite in LEO with respect to an observer on the earth, satellite systems using this type of orbit need to be able to cope with Doppler shifts. Satellites in LEOs are also affected by atmospheric drag that causes the orbit to deteriorate (the typical life of a LEO satellite is 5–8 years, while the typical life of a GEO satellite is 14–18 years). However, launches into LEO are less costly than to the GEO orbit and due to their much lighter weight, multiple LEO satellites can be launched at one time. |

| Medium earth orbits/intermediate circular orbit (MEO/ICO) | These are circular orbits at an altitude of around 10 000 km. Their orbit period is in the range of 6 h. The maximum time during which a satellite in MEO orbit is above the local horizon for an observer on the earth is in the order of a couple of hours. A global communications system using this type of orbit requires a small number of satellites in two or three orbital planes to achieve global coverage. The US GPS is an example of a MEO system. |

| Molniya orbits | See highly elliptical orbits (HEO). A Molniya orbit (named after a series of Soviet/Russian Molniya communications satellites, which have been using this type of orbit since the mid-1960s) is a type of HEO with an inclination of 63,4°, an argument of perigee of −90°, and an orbital period of one half of a sidereal day. |

| Orbit | The path described by the center of mass of a satellite in space, subjected to natural forces, principally gravitational attraction, but occasional low-energy corrective forces exerted by a propulsive device in order to achieve and maintain the desired path. |

| Orbital plane | The plane containing the center of mass of the earth and the velocity vector (direction of motion) of a satellite. |

| Polar orbit | Polar orbits are LEO orbits that are in a plane of the two poles. Their applications include the ability to view only the poles (e. g., to fill in gaps of GEO coverage) or to view the same place on earth at the same time each 24-h day. By placing a satellite at an altitude of about 850 km, a polar orbit period of about 100 min can be achieved (for more continuous coverage, more than one polar orbiting satellite is employed). |

| Sun-synchronous (SS) orbit | A special polar orbit that crosses the equator and each latitude at the same time each day is called a sun-synchronous orbit; this orbit can make data collection a convenient task. Satellites in polar orbits are mostly used for earth-sensing applications. Typically, such a satellite moves at an altitude of 1 000 km. In an SS orbit, the angle between the orbital plane and sun remains constant. This orbit can be achieved by an appropriate selection of orbital height, eccentricity, and inclination that produces a precession of the orbit (node rotation) of approximately 1° eastward each day, equal to the apparent motion of the sun; this condition can only be achieved for a satellite in a retrograde orbit. As noted, SS low-altitude polar orbit is widely used for monitoring the earth because each day, as the earth rotates below it, the entire surface is covered and the satellite views the same earth location at the same time each 24-h period. All SS orbits are polar orbits, but not all polar orbits are sun-synchronous orbits. |

Figure 3 illustrates graphically the various satellite orbits that are in common use. Most of the commercial satellites discussed in this text reside in the GSO.

At the practical level, the GSO has small nonzero inclination and eccentricity, which causes the satellite to trace out a small but manageable “figure eight” in the sky. During normal operations, satellites are “station-kept” within a defined “box” around the assigned orbital slot; eventually (around the end-of-life event of a satellite – usually 15–18 years after launch) the satellite is “allowed” to enter an inclined orbit in the proximity of the assigned orbital slot (unless moved to some other maintenance position): north–south maneuvers to keep the spacecraft at the center box are not undertaken (to save fuel), but east–west maneuvers are maintained to keep the orbital slot.

Orbital positions are defined by international regulation and are defined as longitude values on the “geosynchronous circle,” for example, 101° W, 129° W, and so on. Satellites are (now) spaced at 2° (or 9° for DBS) to allow sufficient separation to support frequency reuse, although in some applications a group of satellites can be (nearly) collocated (but each using a different frequency spectrum). In actuality, an orbital position is a “box” of about 150 km by 150 km, within which the satellite is maintained by ground control. Non-GSO satellites are used for applications such as Satellite radio services, GPS earth sensing, and military applications; however, commercial communication services are also emerging; satellites that operate in Molniya, or MEO, or LEO will add to the bandwidth supply, drive cost down, and in combination with smarter antennas on the ground provide continuous service (in fact, there is an argument to make that multiple satellites provide the ability to reconstitute quickly in the event of an anomaly).

The major consequence of the GSO position is that signals experience a propagation delay of no less than 119 ms on an uplink (longer for earth stations at northern latitudes or for earth stations looking at satellites that are significantly offset longitudinally compared with the earth station itself Depending on the location of the earth station and the target satellite (which determines the look angle), the path length (and so the propagation delay) can vary by several thousand kilometers (e.g., for a satellite at 101° W and an antenna in Denver Co., the “slant” range is 37 571,99 km; for an antenna in Van Buren, ME, the range is 38 959,54 km).x), and no less than 238 ms for an uplink and a downlink or a one-way, end-to-end transmission path. A two-way interactive session with a typical communications protocol, such as Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), will experience this roundabout delay twice (no less than 476 ms) since the information is making two round trips to the satellite and back.

One-way or broadcast (video or data) applications easily deal with this issue since the delay is not noticeable to the video viewer or the receive data user. However, interactive data applications and voice backhaul applications typically have to accept (and adjust) to this predicament imposed by the limitations of the speed of light, which is the speed that radio waves travel. Satellite delay compensation units and “spoofing” technology have successfully been used to compensate for these delays in data circuits. Voice transmission via satellite presently accounts for only a small fraction of overall transponder capacity, and users are left to deal with the satellite delay individually, only a few find it to be objectionable.

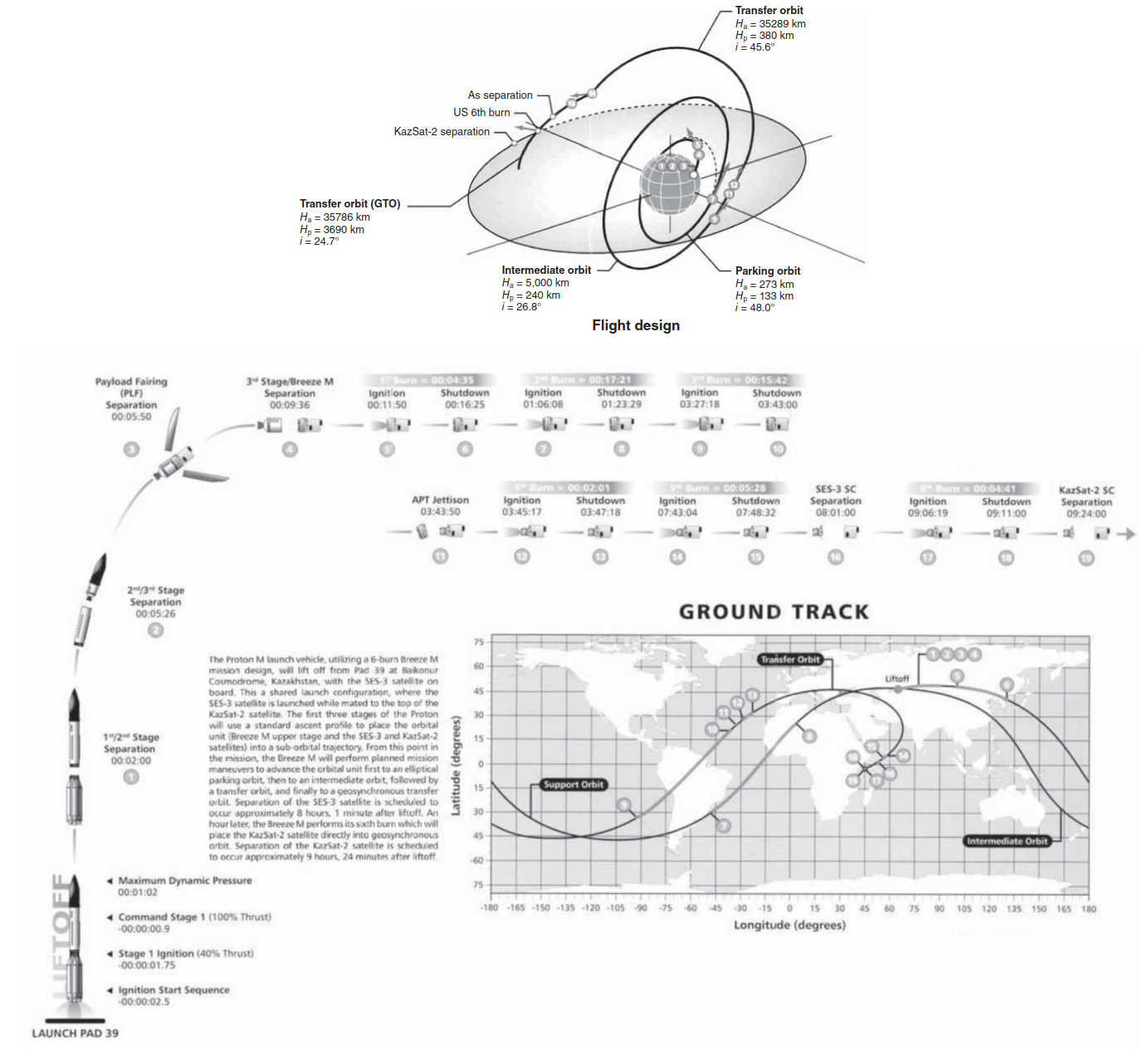

Figure 4 depicts a mission overview for the launching of a mated set of satellites, based on uncopyrighted materials from International Launch Services (ILS); ILS provides mission management and launch services for the global commercial satellite industry using the premier heavy lift vehicle, the Proton Breeze M.

They are one of the three major launching outfits for commercial satellites. The Proton Breeze M launch vehicle launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, operated by the Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos) under the long-term lease from the Republic of Kazakhstan.

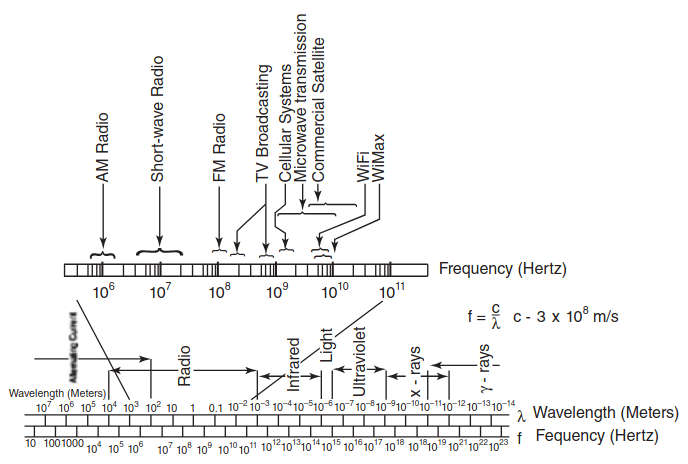

Satellite Transmission Bands

A satellite link is a radio link between a transmitting earth station and a receiving earth station through a communications satellite. A satellite link consists of one uplink and one downlink; the satellite electronics (i. e., the transponder) will remap the uplink frequency to the downlink frequency. The transmission channel of a satellite system is a radio channel using a direct-wave approach, operating in at specific RF bands within the overall electromagnetic spectrum (see table below).

| Electromagnetic spectrum and bands. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Frequency Band | Frequency Range | Propagation Modes | Satellite Frequencies (GHz) | |||

| ELF (Extremely Low Frequency) | Less than 3 kHZ | Surface wave | → | Band | Downlink | Uplink |

| VLF (Very Low Frequency) | 3-30 kHZ | Earth – Ionosphere guided | → | C | 3 700 – 4 200 | 5 925 – 6425 |

| LF (Low Frequency) | 30-300 kHZ | Surface wave | → | X (Military) | 7 250 – 7 745 | 7 900 – 8 395 |

| MF (Medium Frequency) | 300 kHZ – 3 MHz | Surface/sky wave for short/long distances, respectively | → | Ku (Europe) | FS: 10,7 – 11,7 DBS: 11,7 – 12,5 Telecom: 12,5 – 12,7 | FSS: 14,0 – 14,8 DBS: 17,3 – 18,1 Telecom: 14,0 – 14,8 |

| HF (High Frequency) | 3-30 MHz | Sky wave, but very limited, short-distance ground wave also | → | Ku (America) | FSS: 11,7 – 12,2 DBS: 12,2 – 12,7 | FSS: 14,0 – 14,5 DBS: 17,3 – 17,8 |

| VHF (Very High Frequency) | 30-300 MHz | Space wave | → | Ka | ~18 – ~31 GHz | |

| UHF (Ultra High Frequency) | 300 MHz – 3 GHz | → | ||||

| SHF (Super High Frequency) | 3-30 GHz | Space wave. The workhorse microwave band. Line-of-Sight. Terrestrial and satellite relay links | → | V | 36 – 51,4 | |

| EHF (Extremely High Frequency) | 30-300 GHz | Space wave. Line-of-Sight. Space-to-Space links, military and future use | → | |||

Table 2 provides some key physical parameters of relevance to satellite communication. The frequency of operation is in the super high frequency (SHF) range (3–30 GHz). Regulation and practice dictate the frequency of operation, the channel bandwidth, and the bandwidth of the subchannels within the larger channel. Different frequencies are used for the uplink and for the downlink.

| Table 2. Some Key Physical Parameters of Relevance to Satellite Communication | |

|---|---|

| Frequency | The number of times that an electrical or electromagnetic signal repeats itself in a specified time. It is usually expressed in Hertz (Hz) (cycles per second). Satellite transmission frequencies are in the gigahertz (GHz) range. |

| Frequency band | A range of frequencies used for transmission or reception of radio waves (e. g., 3,7–4,2 GHz). |

| Frequency spectrum | A continuous range of frequencies. |

| Frequency spectrum Hertz (Hz) | SI unit of frequency, equivalent to one cycle per second. The frequency of a periodic phenomenon that has a periodic time of 1 s. |

| Kelvin (K) | SI unit of thermodynamic temperature. |

| Msymbol/s | Unit of data transmission rate for a radio link, equal to 1 000 000 symbol/s. Actual channel throughput is related to the modulation scheme employed. |

| Symbol | A unique signal state of a modulation scheme used on a transmission link, which encodes one or more information bits to the receiver. |

| Watt (W) | SI unit of power, equal to 1 J/s. |

| SI = Systeme International d’Unites (International Systems of Units) | |

Frequencies above about 30 MHz can pass through the ionosphere and, therefore, can be utilized for communicating with satellites (frequencies below 30 MHz are reflected by the ionosphere at certain stages of the sunspot cycle; however, commercial satellite services use much higher frequencies. The range 3–30 GHz represents a useful set of frequencies for geostationary satellite communication; these frequencies are also called “microwave frequencies From 30 to 300 GHz, the frequencies are referred to as “millimeter wave”; above 300 GHz optical techniques take over, these frequencies are known as “far infrared” or “quasi optical.”x.” Above about 30 GHz, the attenuation in the atmosphere due to clouds, rain, hydrometeors, sand, and dust makes a ground to satellite link unreliable (such frequencies may still be used for satellite-to-satellite links in space, although these applications have not yet developed commercially Applications are emerging in the military arena: the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) satellite system is a US Government joint service satellite communications system of four satellites (three of which were launched in 2014) that use the EHF spectrum; it is satellite communications system that aims at providing survivable, global, secure, protected, and jam-resistant communications for high-priority military ground, sea, and air assets. According to the US Air Force, AEHF will allow the National Security Council and Unified Combatant Commanders to control their tactical and strategic forces at all levels of conflict through general nuclear war and supports the attainment of information superiority.x).

The actual frequencies of operation of commercial (US) satellites are The international set of microwave bands is as follows: L-band (0,39–1,55 GHz); S-band (1,55–5,20 GHz); C-band (3,70–6,20 GHz); X-band (5,20–10,9 GHz); and K-band (10,99–36 GHz).x:

- C-band: 3,7–4,2 GHz for downlink frequencies and 5,925–6,425 GHz for uplink frequencies;

- Ku-band: 11,7–12,2 GHz for downlink frequencies and 14–14,5 GHz for uplink frequencies;

- BSS: 12,2–12,7 GHz for downlink frequencies and 17,3–17,8 GHz for uplink frequencies;

- Ka-band: 18,3–18,8 GHz and between 19,7 and 20,2 GHz for downlink frequencies and between 28,1–28,6 GHz and 29,5–30 GHz for the uplink frequencies (other specific frequencies are possible as discussed in High Throughput Satellites (HTS) and KA/KU Spot Beam Technologies“Applications and Design Considerations of HTS Satellites” – also, some advanced services at higher frequencies, up to 40 GHz or even higher are possible in the future).

Table 3 depicts in a summarized form, (other) relevant satellite and/or microwave bands (higher frequencies correspond to the millimeter waves, as defined by the absolute value of the wavelength).

| Table 3. Satellite Bands, Generalized View, IEEE Standard 521-1984 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Band Designator | Frequency (GHz) | Wavelength in Free Space (cm) |

| L-band | 1-2 | 30,0-15,0 |

| S-band | 2-4 | 15-7,5 |

| C-band | 4-8 | 7,5-3,8 |

| X-band | 8-12 | 3,8-2,5 |

| Ku-band | 12-18 | 2,5-1,7 |

| K-band | 18-27 | 1,7-1,1 |

| Ka-band | 27-40 | 1,1-0,75 |

| V-band | 40-75 | 0,75-0,40 |

| W-band | 75-100 | 0,40-0,27 |

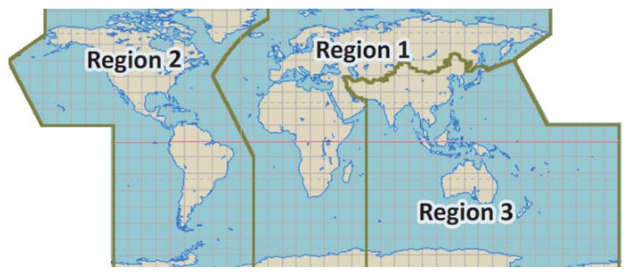

Note that the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) has divided the world into three regions (also see Figure 5):

- Region 1: Europe, Middle East, Russia, and Africa;

- Region 2: The Americas;

- Region 3: Asia, Australia, and Oceania.

Table below provides some additional information on frequency bands.

| (a) Satellite transmission factors and bands. (b) Additional frequency band details for Region 2. | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Band | Characteristics | Considerations |

| C-Band (6 GHz uplink and 4 GHz downlink) | Relatively immune to atmospheric effects | Requires large antennas (3,8-4,5 meters or larger, especially on the transmit side) |

| Popular band, but on occasion it is congested on the ground (see note at right) | Large footprints | |

| Bandwidth (~500 MHz/36 MHz transponders) allows video and high data rates | Best performing band in the context of rain attenuation | |

| Provides good performance for video transmission | Potential interference due to terrestrial microwave systems | |

| Proven technology with long heritage & good track record | ||

| Common in heavy rain zones | ||

| Ku-Band (14-14,5 GHz uplink and 11,7-12,2 GHZ downlink) | Moderate to low cost hardware | Attenuated by rain and other atmospheric moisture |

| Highly suited to VSAT networks | Spot beams generally focused on land masses | |

| Spot beam footprint permits use of smaller earth terminals, 1-3 m wide in moderate rain zones | Not ideal in heavy rain zones | |

| DBS-Band (17,3-17,8 GHz uplink and 12,2-12,7 GHz downlink) | Simplex | Attenuated by rain and other atmospheric moisture |

| Multiple feeds for access to satellite neighborhoods | ||

| Small RO antennas | ||

| TV Video transmission to consumers | ||

| Ka-Band (18,3-18,8 GHz and 19,7-20,2 GHz downlink 28,1-28,6 GHz and 29,5-30,0 GHz uplink) | Micro-spot footprint | Rain attenuation |

| Very small terminals, much less than 1 m | Obstruction interference due to heavily rainfall (Black Out) | |

| High data rates are possible 500-1 000 Mbps | ||

| High Throughput Satellites | ||

The Table of Frequency Allocations contained in Article 5 of the Radio Regulations (RR) allocates frequency bands in each of the three ITU regions to radiocommunication services based on various service categories as defined in the RR. There are some differences worldwide; however, the C-band and Ku-band are generally comparable.

| General Purposes Frequencies | Channel ITU Region 2 GEO Satellite Spectrum.x | Downlink Channel (GHz) | Description | Antenna Size (typical) | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C FSS (standard) | 4,2 | Mainstay of satellite communications | 3-4,5 m for cable headens | 99,95 | |

| Low rain fade | |||||

| 3,7 | High reliability w/ large antennas | ||||

| Application example: Cable TV | |||||

| X-Band | 7,75 | Military Band | Various | 99,95 | |

| 7,25 | |||||

| Extended Ku | 11,45 | 1 GHz split in two allocations | |||

| 10,7 | Not in use due to medium power, regulatory restrictions & terrestrial interference 2 degree separation | 75-95 cm | 99,9 | ||

| Ku FSS standard | 12,2 | Smaller antenna VSAT applications | |||

| 11,7 | 500 MHz used by DTV/Echo for niche (int’l) services | ||||

| 2 degree separation | |||||

| Specific Purposes Frequencies | Ku BSS | 12,7 | DTH applications (high power) | 45-55 cm | 99,85-99,9 |

| 500 MHz by 2nd Gen | |||||

| US DBS | 12,2 | Moderate rain attenuation | |||

| Wider spacing 4,5-9 degree separation | |||||

| Ka BSS | 17,8 | Additional Ka-band available to supplement Ku BSS for DTH applications (D/L 17,3-17,8 Ghz U/L 24,75-25,25 GHz) | 50-60 cm | 99,85-99,9 | |

| Most countries in the Americas have this band available (no FS in the band) for DTH (uplink requires large antenna) | |||||

| US RDBS | 17,3 | Moderate rain attenuation | 4 degree spacing and high power: 50 cm | ||

| ~4 degree separation to enable easier coordination with small receive dishes (FCC) | |||||

| Ka BSS satellites cannot operated co-located with Ku BSS satellites (transmit band same as receive band of a Ku BSS (at least 0,3 degrees of spacing is required to eliminate interference) | 2-3 degree spacing: 60 cm and larger | ||||

| Ka FSS lower band | 1 GHz split into two allocations: 18,3-18,8 GHz | DIRECTV uses lower band | 70-80 cm | 99,8-99,9 | |

| 2 degree separation | |||||

| Ka FSS upper band | 19,7-20,2 GHz (Main) | High rain attenuation | |||

| Small contiguous spot beams of 0,4-1 degree, covering 250-600 km with frequency reuse the capacity increase about 20-fold compared with Ku or Ka widebeam architecture supports high capacity, “bandwidth-on-demand” , Internet access and also point-to-point applications 2-way use, 70 cm dishes when s/c are 2 degrees apart (user beams connected via satellite-associated gateways) large margins needed to address rain attenuation | |||||

| Future Frequencies | Q-band | 50-33 | Future applications | TBD | |

| V-band | 75-50 | ||||

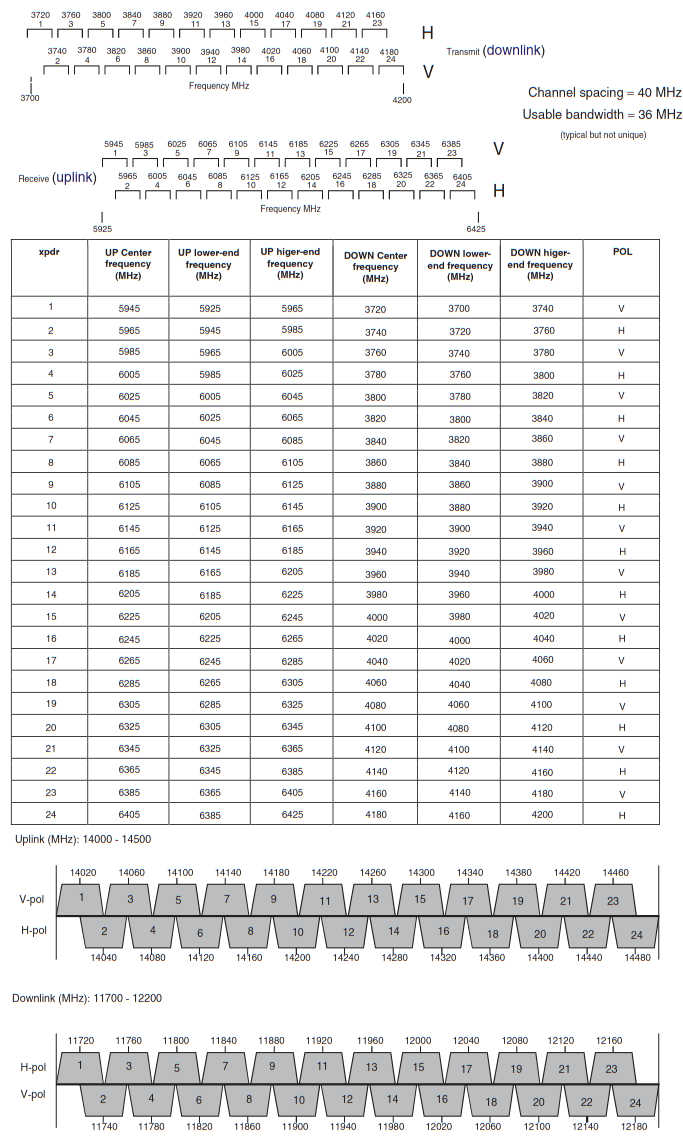

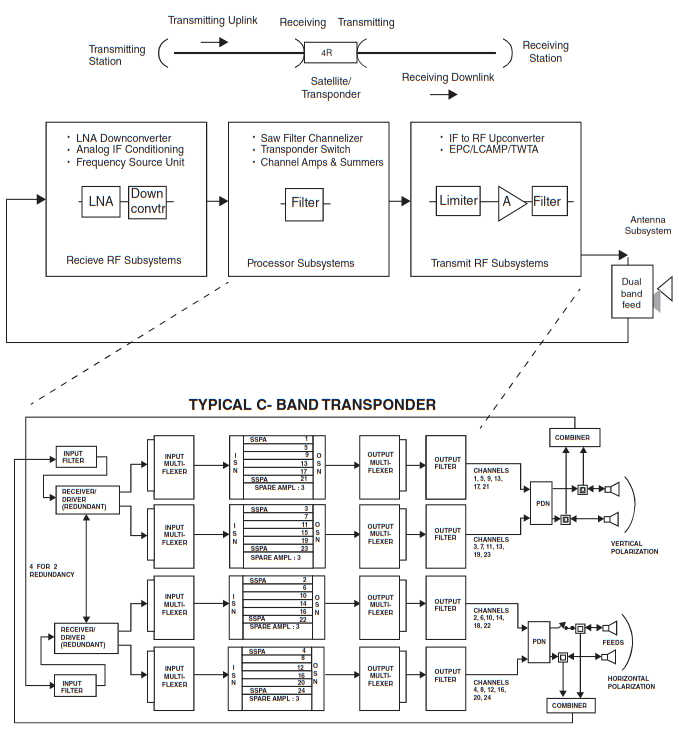

The frequency bands are further subdivided into smaller channels that can be independently used for a variety of applications. Figure 6 depicts a typical subdivision of the C-band into these channels, which are also called colloquially as “transponders” (transponder as a proper term is defined later in the section). The nominal subchannel bandwidth is (typically) 40 MHz with a usable (typical) bandwidth of 36 MHz. Similar frequency allocations have been established for the Ku and Ka bands.

Many satellites simultaneously support a C-band and a Ku-band infrastructure (they have dedicated feeds and transponders for each band). Most communications systems fall into one of three categories: bandwidth efficient, power efficient, or cost efficient. Bandwidth efficiency describes the ability of a modulation scheme to accommodate data within a limited bandwidth. Power efficiency describes the ability of the system to reliably send information at the lowest practical power level. In satellite communications, both bandwidth efficiency and power efficiency are important.

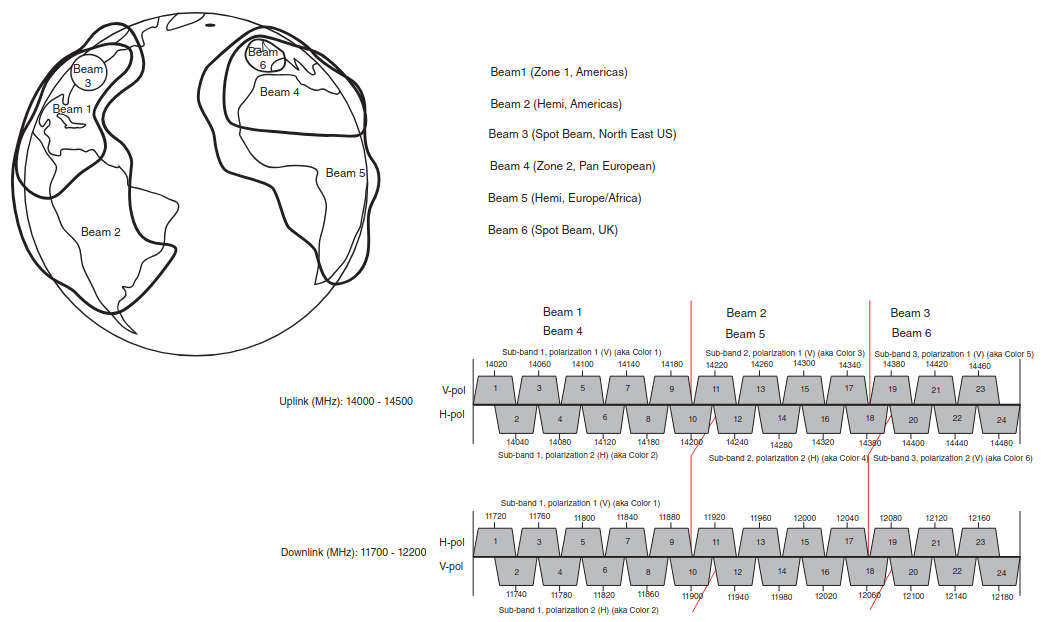

Satellites usually support a number of beams, making use of frequency reuse; the use of a half-a-dozen to a dozen beams if fairly typical. These beams are implemented using different antennas and/or distinct feeds on a single antenna. Each spot beam reuses available frequencies (and/or polarizations), so that a single satellite can provide increased bandwidth. In nonoverlapping regions, the frequencies can be fully reused; in overlapping regions, nonconflicting frequencies have to be employed (see Figure 7 for an example). HTS support up to 100 beams in nonoverlapping geographic areas, thus greatly increasing the total usable throughput.

Figure 8 depicts a two-way satellite link. The end-to-end (remote-to-central point) link makes use of a radio channel, as described earlier, for the transmitting station uplink side to the satellite; in addition, it uses a downlink radio channel to the receiving station (this is also generally called the inbound link). The outbound link, from the central point to a remote, also makes use a radio channel that comprises an uplink and a downlink.

From an application’s perspective, the link may be point-to-point (effectively where both ends of the link are peers) or it may be point-to-aggregation-point, for example, for handoff to a corporate network or to the Internet. Some applications are simplex, typically making use of an outbound link; other applications are duplex, using both an inbound and an outbound link.

Satellite communications now almost exclusively make use of digital modulation. Modulation is the processes of overlaying intelligence (say a bit stream) over an underlying carrier so that the information can be relayed at a distance. Demodulation is the recovery, from a modulated carrier, of a signal having the same characteristics as the original modulating signal. The underlying analog carrier is superimposed with a digital signal, typically using 4-, or 8-point Phase Shift Keying (PSK) techniques, or 16-point Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM). In addition, the original signal is fairly routinely encrypted and, invariably, protected with Forward Error Correction (FEC) techniques.

As noted, different frequencies are used for the uplink and downlink to avoid self-interference, following the terrestrial microwave transmission architecture developed by the Bell System in the 1940s and 1950s. In systems using the C-band, the basic parameters are 4 GHz in the downlink, 6 GHz in the uplink, 500 MHz bandwidth over 24 transponders using vertical and horizontal polarization (a form of frequency reuse discussed later on), resulting in a transponder capacity of 36 MHz or 45–75 Mbps or more of usable throughput – depending on modulation and FEC scheme. C-band has been used for several decades and has good transmission characteristics, particularly in the presence of rain, which typically affects high-frequency transmission.

Read also: Empowering Global Communication with INMARSAT Satellites in shipping

Generally C-band links are used for TV video distribution to headends and for military applications, among others. A number of antenna types are utilized in satellite communication, but the most commonly used narrow beam antenna type is the parabolic dish reflector antenna. C-band receive-dishes for broadcast-quality video reception are typically 3,8–4,5 m in diameter. The size is selected to optimize reception under normal (clear sky) or medium-to-severe rain conditions; however, smaller antennas of 1,5–2,4 m can also be used, depending on the intended application, service availability goals, and satellite footprint. For a two-way transmission, the same size and considerations apply (although larger antennas can also be used in some applications, especially at a major earth station); availability, acceptable bit error rate, satellite radiated power, and rain mitigation goals drive the design/size of the antenna and ground transmission power.

Enterprise applications tend to make use of the Ku-band because of the fact that smaller antennas can be employed, typically in the 0,6–2,4 m (depending on application, desired availability, rain zone, and throughput). Newer applications, typically for DBS/Direct to Home (DTH) video distribution look to make use of the Ka-band, where antenna size can range from 0,3 to 1,2 m (see Table 4).

| Table 1.4. Frequency and Wavelength of Satellite Bands | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (GHz) | Wavelength (m) | Typical Antenna Size (m) |

| 3,7 | 0,081081081 | 1,2-4,8 |

| 4,2 | 0,071428571 | |

| 5,925 | 0,050632911 | |

| 6,425 | 0,046692607 | |

| 11,7 | 0,025641026 | 0,6-2,4 |

| 12,2 | 0,024590164 | |

| 12,7 | 0,023622047 | |

| 18,3 | 0,016393443 | 0,3-1,2 |

| 18,8 | 0,015957447 | |

| 19,7 | 0,015228426 | |

| 20,2 | 0,014851485 | |

| 27,5 | 0,010909091 | |

Spread spectrum techniques and other digital signal processing are being used in some applications to reduce the antenna size by reducing unwanted signals (either in the uplink, e. g., with spread spectrum, or in the downlink with adjacent satellite signal cancellation using digital signal processing).

Related to the issue of orbits note, as stated, that there are multiple satellites in the geostationary orbit: typically every 2° on the arc, and even collocated at the “same” location, when different operating frequencies are used. Effectively, satellite systems may employ cross-satellite frequency reuse via space-division multiplexing; this implies that a large number of satellites (even neighbors) make use of the same frequency operating bands, as long as the antennas are highly directional. Some applications (e. g., direct broadcast to homes) or some (non-US) jurisdictions allow spacing at 3°; higher separation reduces the technical requirements on the antenna system but results in fewer satellites in space. DBS satellites are usually 9° apart on the orbital arc.

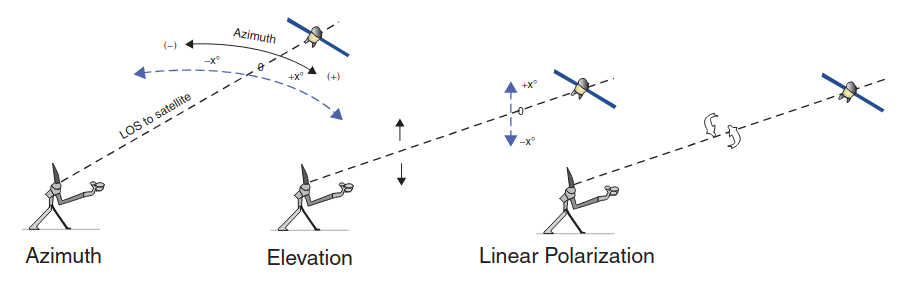

Unfortunately, unless the system is properly “tuned” by following all applicable regulation and technical guidelines, ASI can occur. A transmit earth station can inadvertently direct a proportion of its radiated power toward satellites that are operating at orbital positions adjacent to that of the wanted satellite. This can occur because the transmit antenna is incorrectly pointed toward the wanted satellite, or because the earth station antenna beam is not sufficiently concentrated in the direction of the satellite of interest (e. g., the antenna being too small). This unintended radiation can interfere with services that use the same frequency on the adjacent satellites. Interference into adjacent satellite systems is controlled to an acceptable level by ensuring that the transmit earth station antenna is accurately pointed toward the satellite, and that its performance (radiation pattern) is sufficient to suppress radiation toward the adjacent satellites. In general, a larger uplink antenna will have less potential for causing adjacent satellite interference, but will generally be more expensive and may require a satellite tracking system.

Similarly, a receive earth station can inadvertently receive transmissions from adjacent satellite systems, which then interfere with the wanted signal. This happens because the receive antenna, although being very sensitive to signals coming from the direction of the wanted satellite, is also sensitive to transmissions coming from other directions. In general, this sensitivity reduces as the antenna size increases. As for a transmit earth station, it is also very important to accurately point the antenna toward the satellite in order to minimize ASI effects. As noted, spread spectrum techniques and other digital signal processing are being used in some advanced (but not typical) applications to reduce unwanted signals (e. g., with spread spectrum or with ASI cancellation by using digital signal processing). An industry push is afoot to add an identifying ID to the signal by the modem, called Carrier ID. The Carrier ID allows one to identify the source of the transmission, and, thus, enables one to be better equipped to rectify any spurious signal reaching an (unintended) satellite.

The sharing of a channel (colloquially, a “transponder”) is achieved, at this juncture, using Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), random access techniques, Demand Access Multiple Access (DAMA), or Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) (spread spectrum). Increasingly, the information being carried, whether voice, video, or data, is IP-based.

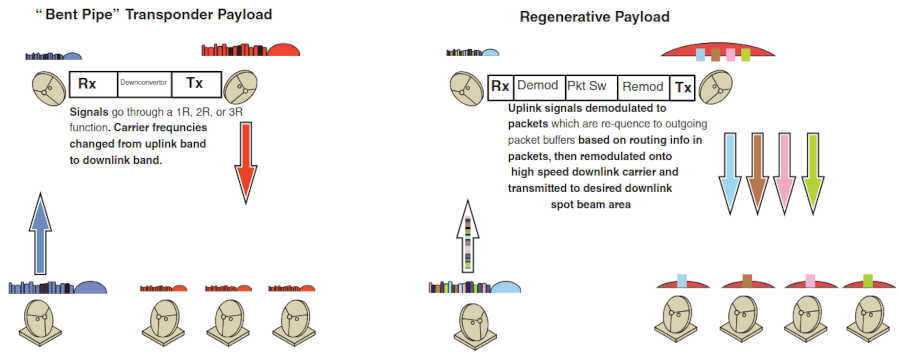

Satellite Signal Regeneration

In general, the information transfer function entails the bit transmission across a channel (medium). Since there is a variety of media in use in communication, many of the transmission techniques are specific to the medium at hand. In the context of this book, the transmission channel is a radio channel.

Typical transmission problems include the following:

- Signal attenuation (e. g., free space loss or attenuation due to “rain fade”);

- Signal dispersion;

- Signal nonlinearities (due, for example, to amplification or propagation phenomena);

- Internal or external noise;

- Crosstalk (e. g., spectral regrowth), intersymbol interference, and intermodulation, and;