The Piracy Golden Age generally refers to a period from the late 17th century to the early 18th century, roughly from the 1650s to the 1730s. This era is characterized by the proliferation of piracy in the Caribbean Sea, along the American coast, and in the waters around the Indian Ocean and West Africa.

- Defining the Terminology, Early Historical Accounts of Maritime Crime, Outlining the Golden Age Defining the Term «Pirate»

- A Brief History of Piracy

- Outlining the Golden Age of Piracy

- Prelude to the Golden Age: Events in Europe, Early Pirate Bases

- Events in Europe Prior to the Golden Age of Piracy

- Early Pirate Bases

- Rise of Piracy: Prominent Pirates and Their Exploits

- The Buccaneering Period (1650-1680)

- Sir Christopher Myngs

- Henry Morgan

- David Marteen

- Laurens de Graaf

- Nicholas van Hoorn

- François L’Olonnais

- Roche Braziliano

- The Pirate Round Period (the 1690s)

- Thomas Tew

- Henry Every

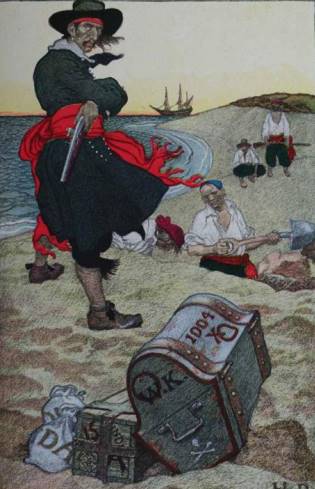

- William Kidd

- Adam Baldridge

- The Interim Period: The War of the Spanish Succession

- Post-Succession Period (1715–1726)

- Benjamin Hornigold

- Charles Vane

- Edward Teach (Blackbeard)

- Stede Bonnet

- Howell Davis

- Calico Jack Rackham

- Anne Bonny

- Mary Read

- John Taylor

- Bartholomew Roberts (Black Bart)

- Abraham Samuel

- James Plantain

- The End of the Golden Age: Woodes Rogers and the End of Prominent Pirate Captains

- Woodes Rogers

- The End of Prominent Sea Captains

- Life at Sea: Typical Activities Aboard the Pirate Ship, the Pirate Look, the Pirate Code, On-Deck Atmosphere

- Typical Activities Aboard the Pirate Ship

- The Pirate Look

- The Pirate Code

- On-Deck Atmosphere

- Myth vs. Fact: The Growth and Expansion of the Romanticized Pirate, Early Written Works on the Subject, Modern Misinterpretations of the Golden Age

- Early Written Works on Piracy

- The Growth and Expansion of the Romanticized Pirate

- After the Golden Age: Piracy and Maritime Law Enforcement

- Conclusion

The Piracy Golden Age has left a lasting legacy in popular culture, inspiring countless books, movies, and folklore. The romanticized image of pirates as swashbuckling adventurers continues to captivate audiences today.

Defining the Terminology, Early Historical Accounts of Maritime Crime, Outlining the Golden Age Defining the Term «Pirate»

Most people have a vague idea of what a pirate is, and if we were to break it down in the simplest terms, the definition would be «an individual who attacks and robs ships at sea». However, this definition is not particularly helpful since it omits more than a few details. The most important detail is who the attacker is. Sir Francis Drake, for example, would routinely attack and rob ships at sea, but if you were his fellow English citizen and you were to call him a pirate back in the day, he would be offended. Of course, if you were Spanish, i. e., Drake’s enemy in combat, and used the same term to describe him, he wouldn’t much care. As an aside, Drake was a prominent privateer who died in 1596, half a century before the beginning of what we call the Golden Age of Piracy. Though he perfectly fits the personalities and experiences of many pirates described in this tome, he was active long before any of them were even born.

Over the years, the sea brigands were referred to by various names interchangeably. Terms like:

- «corsair»;

- «buccaneer»;

- «privateer»;

- and others were bandied around as synonyms to the term «pirate».

However, they are not the same. The confusion becomes even bigger when the terms overlap, as certain people involved with maritime activities would essentially shift from, for instance, being a privateer to being a pirate and vice versa. With that in mind, it is instrumental to define these terms as best as possible. «Pirate» is a universal term for any type of crime that involves a huge body of water and a boat of any size. In other words, you can have sea pirates, lake pirates, river pirates, etc. Furthermore, the crimes don’t even have to happen at sea. If you were a shipowner or a crew member, and you were committing crimes on land:

- looting;

- robbery;

- rape;

- murder;

- gambling;

- smuggling, etc.

you were a pirate. The word itself is Greek in origin, read as πειρατής (peiratḗs) and meaning «brigand».

So, what about the other terms? Let’s start with «corsair». The term itself is French, originally written as corsaire, and it draws its roots from the Latin word cursus, meaning hostile attack or plunder. In other words, it draws roots from an illegal act, so it’s linked to piracy, at least to some extent. However, the French did not use the term «corsair» for illegal activities when related to their own seamen. In fact, the term was specifically related to privateers from the small harbor town of Saint-Malo in the northwestern region of Brittany. Over time, Europeans would also refer to Muslim privateers from the African Barbary Coast as «Barbary corsairs» or «Turkish corsairs», though, in reality, these seafaring folks from Africa would not always be privateers. Sometimes, they were legitimate naval commanders from the Ottoman Empire; other times, they would be regional lords and outlaws, thus making them outright pirates. Furthermore, they were not all Berbers (a term used for the African native groups living in what is today Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia). Since the Ottoman-commissioned Barbary corsairs would often attack Christian ships and wage war against the Christian soldiers, the term «corsair» also gained a bit of a religious undertone.

When we break it down, corsairs are effectively privateers. But what is a privateer? As its name suggests, it refers to a private vessel not owned by the state or the monarch. The term also refers to the officer in charge of the ship. To put it simply, both Sir Francis Drake and his vessel, Golden Hind, are privateers.

A privateer would work outside of the navy as a free agent mainly because there was no real royal navy among any of the seafaring empires during the Late Middle Ages. His job (more than 99 percent of privateers were men at the time) was usually to plunder and attack ships that belonged to nations against which his country was warring. For example, Amaro Pargo, a Spanish corsair/privateer, made a name for himself by attacking mostly English and Dutch ships. Richard Hawkins, one of Drake’s men, also became famous for attacking ships that belonged to the Spanish Armada. But the activity of a privateer was not limited to warfare. In fact, it was expected they would go after merchant ships and other vessels that carried precious cargo. Not only would it provide rich plunder for them and their monarch, but it would also significantly cripple the economic well-being of a rival country. For that reason, a privateer of one country would be a notorious pirate of another. Both Oruç Reis (known as Oruç Barbarossa in Europe due to his ginger beard) and his brother Hayreddin (a later Ottoman navy admiral and beylerbey – «chief governor» – of Ottoman North Africa) were known as fierce pirates among the Western European sailors but were hailed as heroes and loyal subjects in the Ottoman Empire.

Of course, each privateer would be granted full permission from their monarch to plunder ships; these written permissions are called letters of marque, and every Western Christian nation, from Spain, Portugal, and France to England and the Netherlands, issued these permissions. Naturally, the permissions would be null and void the very second the two countries made peace, as doing so was seen as an act of goodwill and a step toward smooth peace negotiations. An immediate annulment of a letter of marque would leave privateers unsatisfied, which is, in fact, one of many contributors to the rise in piracy during the several decades that comprise the Golden Age.

While privateers had permission by the state to do whatever they wanted to an enemy ship, their actions were really no different from those of a common pirate. They would frequently be just as monstrous and brutal as some of the worst outlaws in maritime history. For these reasons and more, people, even back then, would consider privateering nothing more than state-sanctioned piracy. The letter of marque was really the only thing separating a privateer from a life of outright piracy, hence why such a document was incredibly important, legally speaking. Owning a letter of marque could get privateers a lenient sentence in case they went over the line.

Unlike corsairs, privateers were not always religiously motivated, although religion did play a huge part in their activities. For example, most of the privateers would prey on ships from nations with a completely different theological background. England and the Netherlands, two heavily Protestant countries, would wage war with Spain and Portugal, whose majority of people were staunch Catholics. But to a privateer, the target ship merely had to come from a nation with which their homeland was at war. In other words, if England and the Netherlands were skirmishing, Dutch ships would become fair game to privateers and vice versa.

Finally, there’s the term «buccaneer» to consider. If corsairs were linked to the Mediterranean Sea and privateers to the Protestant nations of the Atlantic and Western Europe, buccaneers found their place in the Caribbean, more specifically in the islands of Hispaniola (divided into the Dominican Republic and Haiti today) and Tortuga (just north of Haiti). The name itself derives from the French (or rather Caribbean Arawak) word «buccan». A buccan was a type of wooden framework that hunters would use to either slow-roast or smoke meat. Interestingly, buccaneers were originally nothing more than French-born hunters who settled in Hispaniola and made their living from hunting wild game.

With the Spanish efforts to cleanse most of their West Indies’ territories from French interlopers, the early buccaneers moved to Tortuga, a far smaller isle than Hispaniola with fewer natural resources. This course of events pushed them further into piracy, and soon enough, they would be attacking Spanish galleons with alarming frequency, prompting other nations such as the Dutch and the English to provide them with letters of marque and employ them as privateers. Some of the biggest names among the buccaneers, including Daniel Montbars and François L’Olonnais, would be active during the very early days of the Golden Age of Piracy. While they are often counted among some of the most famed pirates of their time, they were effectively privateers or regular seafarers (or not even seafarers at all) who were pushed into effective piracy by the Spanish.

As you can see, there are so many overlapping themes that we can almost forgive people for conflating all of these terms. And to make matters worse, it is sometimes incredibly difficult to pin down what these men exactly were, despite how other contemporary people described them or even despite how these men described themselves. The famous (or rather infamous) Captain William Kidd, as we will see later in this volume, vehemently denied that he was a pirate, constantly proclaiming that he was hired as a buccaneer, which was not false. However, he did commit acts (or rather, some acts were attributed to him) that would undeniably be linked to piratical activity. In addition, former pirates like Benjamin Hornigold would turn to become pirate hunters, privateers, or regular merchants with a proper pardon from the monarch. Therefore, legally speaking, they would not be referred to as pirates, at least not until they broke the conditions of their pardons and struck a merchant ship again. In addition, false accusations of piracy were common during those years, especially among seamen who felt unsatisfied with the conditions on their ships or who simply felt mutinous for one reason or another. Despite all of that confusion regarding terminology, the undeniable fact remains that pirates did, indeed, exist, and their exploits are just as complicated as anything else in society can be.

A Brief History of Piracy

Most of the terms related to piracy that we’ve listed above stem from either the Middle Ages or modern times. However, the very act of piracy itself is quite old. To put it in the simplest terms possible, maritime crime is as old as seafaring itself. In antiquity, Tyrrhenians, Phoenicians, and Illyrians all frequently dabbled in piracy, while in ancient Greece, it was considered a legal and morally justified venture (though this changed in later years). In fact, a rather famous anecdote from antiquity regarding pirates involves none other than the most famous Roman ruler ever, Gaius Julius Caesar. On his voyage across the Aegean Sea, the former priest-turned-military commander Caesar was captured by a group of Cilician pirates. They reportedly ransomed him for a sum of twenty talents of silver. For reference, one talent roughly corresponds to 33 kilograms of raw metal, so in today’s currency, that would be around $25 040 per talent, making the ransom $500 080. Caesar, however, felt insulted by this ransom, demanding that they raise it to fifty talents, or $1 252 000 in today’s money. During Caesar’s captivity at the island of Pharmacusa (modern-day Pharmakonisi), a small section of the Dodecanese Islands off the coast of modern-day Turkey, he promised that he would crucify each and every one of his pirate captors, which they took as a joke. As soon as his ransom was paid and he was back in Rome, Caesar raised a massive fleet, hunted down his former captors, and captured them. True to his word, he crucified them all, but he did show a bit of leniency by having their throats cut so they could die quickly.

The Early Middle Ages also saw lots of pirate activity. Vikings of Scandinavia were constantly raiding the European coast with plenty of success, and their seafaring warriors would frequently go after the British Isles as well, which even led to early Scandinavian settlements in what would later become England. Off the coast of modern-day Netherlands, the Frisian sea brigands would often attack the Holy Roman Empire’s ships, with the most prominent commanders being Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijerd Jelckama. The south Mediterranean coast of Europe was under constant assault by the so-called Moorish pirates, while the Slavic tribe known as the Narentines would frequently raid the Adriatic coast. People across Europe had their own brand of pirate attackers to worry about, and brigands would vary in nationality, culture, and efficacy. Anyone, from the Baltic Slavs and Cossacks to the Arabians and Greek Maniots, could be atop a ship’s deck and raiding the nearest seaborne merchant vessel. And while there were exceptions to the rule in every century of European history, pirates were considered a threat to society and criminals who deserved brutal punishment.

Of course, piracy is by no means limited to Europe. In fact, entire armadas of pirates could be found in ancient and medieval:

- China;

- Japan;

- Vietnam;

- and the many Indian states.

There were even pirates off both the east and west coasts of Africa. In fact, many of these ships would actually come across European vessels, and depending on the relations between the countries, there would either be plundering or a peaceful departure. In fact, if a piratical act were to take place between, for example, the English and the Mughal Empire of India, it would amount to a political scandal, and we intend to cover one such event later in this book.

Every single navigable ocean has seen its fair share of piracy throughout the entirety of human history, and each culture would have differing views on piracy as a phenomenon. As you will see later, despite the act being highly illegal and condemned by society, there were even contemporary citizens that found the lifestyle fascinating. Millions of people would willingly abandon their regular lives and sail the seven seas looking for plunder.

Outlining the Golden Age of Piracy

Defining what exactly the Golden Age of Piracy was can be a bit daunting, especially considering the whole issue of defining the terms such as «pirate» or «privateer». Most experts would agree that there were roughly three periods that marked the so-called Golden Age, and they use several different factors when considering this issue. Firstly, in order for a time span to be the Golden Age of anything, there has to be an increase in frequency. Next, there has to be an exact cut-away point, i. e., a point in time where a certain activity starts to significantly wane or stop altogether. Finally, a Golden Age has to show certain trends in society, trends that would set the stage for the Golden Age to take place and thrive.

In relation to piracy itself, there are a few issue-specific factors to consider. Firstly, a Golden Age of piracy has to have prominent personalities that marked the age, so much so that they became the very stuff of legends. Next, for pirates to thrive, they need safe ports and places to congregate, i. e., semipermanent or permanent pirate settlements. Lastly, the extent of piracy has to be so significant that it actually leads to changes in legal proceedings and gain attention from the very top of the state.

When we take every single factor listed above into consideration, we can more or less connect the dots and draw a concrete timeline of the Golden Age of Piracy. Most experts (though not all) would divide the Golden Age into three separate time periods, all perfectly leading one into the other. Those three would be:

- The buccaneering period (roughly between the early 1650s and 1680).

- The Pirate Round period (throughout the 1690s).

- The period immediately following the War of the Spanish Succession (between 1715 and 1726).

Before we move on, we should address a few discrepancies. Namely, despite the fact that the Golden Age, as outlined above, lasted around seventy-five or more years, it is by no means the only period with massive surges and resurgences in piracy. Typical Activities Aboard the Pirate Ship, the Pirate CodePiratical activities in the Mediterranean and in Southeast and East Asia were well underway for centuries before the buccaneers took up arms against the Spanish. On top of this, the piratical attacks did not necessarily decrease after the deaths of the most prominent pirates of the Caribbean in the late 1720s. In fact, some of the fiercest pirates in the world actually rose to prominence an entire century later, including one of the most successful female pirates to date, a former Chinese prostitute and pirate leader named Zheng Yi Sao. However, that topic is widely outside of the scope of this book.

Furthermore, these facts don’t take away from the historical and cultural importance of the Golden Age of Piracy. It would, indeed, be this particular period that would push the pirates into the global mainstream, and some of the most prominent images we have of pirates today, complete with misconceptions and false attributions, will come from this exact timespan. Events in this particular age would directly influence the creation and standardization of national navies and the improvement of conditions of a common sailor. As odd as it might seem, the pirates that operated during these three-fourths of a century had a far more profound influence on the world than historians and everyday people give them credit for.

Prelude to the Golden Age: Events in Europe, Early Pirate Bases

Events in Europe Prior to the Golden Age of Piracy

In the early 17th century and beyond, Europe was a colossal battlefield due to a series of skirmishes known collectively as the European wars of religion. Nearly every single major European power was involved, including:

- England;

- France;

- the Netherlands;

- Spain;

- Portugal;

- the Holy Roman Empire;

- the Italian lands;

- and the Scandinavian kingdoms.

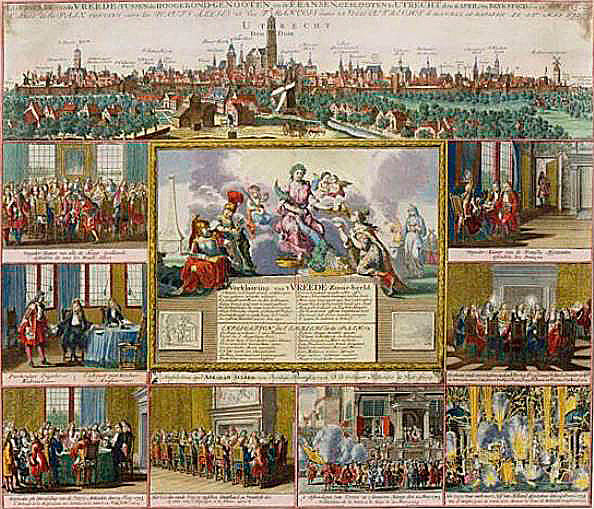

While religion was one of the main motivators behind these conflicts, with the rise of Protestant factions in Christianity and the waning Catholic influence over much of Western Europe, they were far from the only factor. Oftentimes, two Catholic or Protestant nations would clash against one another while allied with a country that would be deemed an enemy. Some of the bloodiest wars took place during these times, including the Thirty Years’ War within the Holy Roman Empire (1618-1648), The Eighty Years’ War, also known as the Dutch War of Independence (1568-1648), and the War of the Three Kingdoms that involved England, Scotland, and Ireland (1639-1651). Moreover, the wars in England would directly lead to Oliver Cromwell overthrowing the king and establishing himself as Lord Protector of the Realm, effectively making England a republic for the first and, so far, final time in its existence.

Also, during this turbulent period, European maritime forces started colonizing other corners of the globe, creating new trade routes and importing brand-new products and raw materials. The English East India Company was still in its infancy, and both the French and the Portuguese were already active in the Indian Ocean. Of course, the future colonizers also sought good fortune across the Atlantic, with both Americas seeing a lot of activity.

The most prominent scrambles for supremacy in the region, however, happened in the so-called West Indies or the Caribbean. The many islands that comprise the region would serve as bases for several great European powers, with Spain holding sway until the waning years of the 17th century. Many seafarers of French, Dutch, and English origin found their calling here either as plantation owners, hunters, sailors, or outright pirates. As the decades went by, more and more territories were ceded from Spain to the other European powers. For instance, Jamaica was held by the Spanish until 1655, when Admiral William Penn conquered it and subjugated it to English rule. In addition, the western part of Hispaniola was Spanish, though the French managed to establish a settlement there in 1670, with the western half of the island officially being ceded to France nine years later. This region would eventually become Haiti.

The ethnic makeup of these islands was interesting, to say the least. Each island had its own native population of various people groups, and interbreeding with Europeans was common at the time. However, most invading powers also imported thousands of slaves from Africa to the region, therefore further diluting the native population. Because of so many various people groups essentially being forced to work side by side with one another on a daily basis, they had to find a way to interact, which led to the creation of early Creole languages.

Interestingly, the trade route from the Caribbean to Europe was not the busiest, as most Europeans still frequently traded with East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The powerful Mughal Empire was still the dominant force, both on land and at sea, having reached its peak during the reigns of two rulers known as the Great Moghuls colloquially – Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658) and especially Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707). The empire’s influence was so vast that it could wipe out any of the European trading companies in an instant. The English East India Company, in particular, was essentially forced into keeping good relations with the empire, considering they only had a few factories on the subcontinent at the time. More importantly, the region was known for its spices and other materials, of which the European elites were incredibly fond. Foreign ships had to maintain their strenuous relationships with the Mughal Empire as best as they knew how, and that meant preventing any piratical activity from targeting Indian merchant ships. With the wars in Europe draining the court treasuries and the colonies growing increasingly restless, violent, and – most importantly – lawless, the seeds were sown for the first prominent pirates to emerge.

Early Pirate Bases

One common myth, which we will delve into deeper a bit later, was that the pirates during the Golden Age were so prominent that they essentially established a «Pirate Republic», which was free from all European powers and responsible only to itself and its maritime citizens. However, nothing can be further from the truth. Throughout the Golden Age, there was no such thing as a pirate utopia. However, pirates did often congregate in specific areas, be they small islands or port towns. Unsurprisingly, they were all prominent spots on major trade routes, and even less surprisingly, they were all spots where illegal trade was allowed and where officials turned a blind eye to contraband retail.

Before we move onto the prominent pirate bases themselves, we should discuss the legal activities of maritime empires at the time. It is no secret that the law had little to no effect in certain corners of huge seafaring empires. However, the laws regarding trade were not that different from our own in the 21st century. For example, if a person came into possession of a huge sum of wealth overnight, the matter would be investigated thoroughly. Seafarers, in particular, were subject to these investigations, considering the prominence of piracy and the insecurity of contemporary ocean trade. Moreover, if pirates from one country attacked ships that belonged to an ally nation, the matter would become an international incident, and unless the native authorities dealt with the issue, the matter could easily lead to war.

These matters became exceptionally difficult during times when peace treaties were signed between two nations. Back in the day, news traveled slow, especially across the ocean. So, if, for instance, Spain and England signed a treaty that demanded an end to all hostilities, privateers on either side would have to cease attacking ships from their former enemies. Since said news would sometimes take months to reach people outside of Europe, a privateer could easily attack a ship, thinking they were doing so fully protected by the law. In reality, though, the attack would be considered an act of aggression and a breach of the treaty, resulting in another potential war or monetary compensation. It was a vicious circle and a legal nightmare for everyone involved.

Of course, these factors were not the only ones that played a major role in forming regular pirate bases. In fact, everyday seafaring might have been far more influential in that regard. Generally speaking, if you were a sailor in the mid- to late 17th century and early 18th century, no matter what country you were living in, you would be living a miserable life. Average wages of common sailors were incredibly low, and most people who held high positions, such as admirals or captains, didn’t fare much better during a typical nautical voyage. More importantly, as a sailor, your chances of advancing to a ranked position were almost impossible. You would essentially be risking life and limb to import some fabric, spices, wood, and other raw materials, and those risks would seemingly come from everywhere. You might die from malnutrition, drown at sea due to a storm, be killed by locals in any number of non-European ports, get stranded somewhere for even the slightest insubordination, contract and succumb to one of countless diseases, be murdered by the local wildlife, end up being sold into slavery if you had the misfortune of being attacked by a slave-selling nation, and, of course, be killed by pirates. And to make matters worse, you would be at the mercy of your commanding officer, and your amenities were practically non-existent. The job essentially trapped you into a life of utter misery.

Compared to these conditions, the life of piracy was almost seen as a blessing, although working aboard a pirate ship was no better than being on an ordinary vessel in terms of simple living and working conditions. Many young men turned to piracy for the same reason they would become factory workers in the ever-growing East India Company – it was a position that would, at the very least, offer them new wealth and a chance to be, to a certain extent, their own bosses. The main difference, of course, was the social attitude toward the men who chose these career paths. East India Company employees, be they ordinary workers, factors (mercantile fiduciaries of the EIC), writers, etc., were usually disliked by the English upper classes, but their work was not illegal or even particularly unethical for the time. Piracy, on the other hand, was an out-and-out crime, and few men actually confessed to being pirates openly. In fact, the punishments for acts of piracy were severe, usually consisting of hanging, beheading, being drawn and quartered, or a combination of these acts. Furthermore, a pirate’s body would usually be coated in tar or hung in chains above a prominent port as a reminder to other seafarers what awaited them if they turned to piracy. Despite all of that, thousands of men, usually those in their twenties, would opt to sail under the black flag and, if necessary, die under it.

An average successful pirate ship could haul in massive booty. And considering their targets were usually massive galleons that transported tons of goods and valuables, a typical pirate could earn himself a wage that was hundreds of times larger than a regular sailor’s daily salary. Naturally, a pirate ship would need a safe place to deposit all of the riches stolen from a ship, mainly because the authorities would certainly get suspicious if a small, ill-fit vessel entered a harbor and its sailors, all poorly dressed and lacking in basic manners, were in possession of exotic goods worth tens of thousands of pounds. Not only would pirates need a port at which to resell all of their stolen goods quickly, but they also required an area where they might rest, eat, drink, enjoy a woman or two, and repair their ships. Such ports already existed in the Mediterranean, with the Barbary Corsairs using them prominently, but as the decades progressed, a few new key areas arose as potential pirate bases, one of which would serve as the potential inspiration for a fictional pirate utopia.

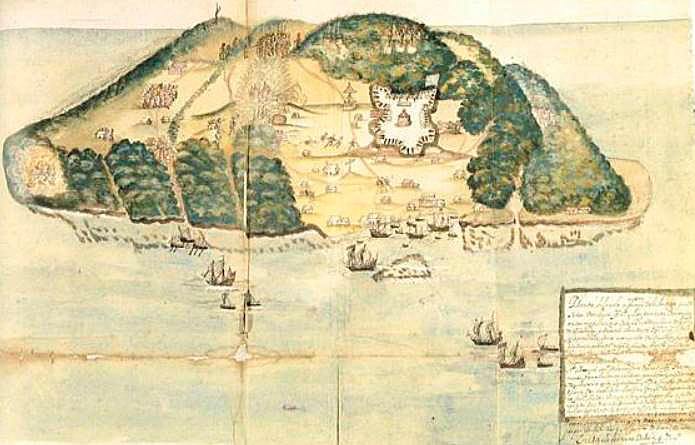

One of these ports was Tortuga, a small island north of Hispaniola. Originally settled by the Spanish in 1625, it would be the home base of French buccaneers, as well as both English and Dutch pirates, for many decades, with the Spanish retaking and losing the island several times. By 1640, the French eventually built a permanent fortress on the island called Fort de Rocher, allowing them to fend off Spanish attacks in the coming years. And even as the piratical activity moved to different islands in the region, some of the most Review of Pirate Tactics in Ship Combatfamed pirates of the time, including Henry Morgan, frequented Tortuga. Morgan would be an instrumental member of the so-called Brethren of the Coast, a very loosely connected group of seafaring outlaws mostly of French Huguenot and British Protestant descent. This brotherhood was, to an extent, responsible for making the Caribbean an economic hub thanks to their illegal trade, and many of the pirates would try to retire on the islands as farmers or plantation owners with varying success.

West of the Caribbean, within Mexico, we find another early pirate base, the town of Campeche. Originally a trading town formed in the 1540s, the place would become a hotbed of piracy, with the Spanish government unable to quench the problem for at least a century and a half. Sir Francis Drake was one of the first privateers to sail the waters near Campeche, but the city itself would host, in one way or another, a vast array of famous pirates, buccaneers, privateers, and other men of the sea. Possibly the most famed men to be in or near the city were the brutal French buccaneer Jean David Nau (better known as François L’Olonnais), Dutch mercenary and pirate Laurens de Graaf, and the renowned Welsh pirate and later lieutenant governor of Jamaica, Sir Henry Morgan. In fact, Morgan would be one of many seafaring bandits that would sack Campeche and rob it of its riches.

Staying within the Caribbean, we move onto possibly the most famous bases for any pirate during the Golden Age, namely Nassau on the island of New Providence (the Bahamas) and Port Royal in Jamaica. Port Royal was inhabited as early as 1494 by the Spanish, but it officially became an English territory in 1655 after a successful invasion. Around the same time, the Bahamas were being settled, with New Providence getting its first settlement in 1666. Charles Town, the fort (and later the town), was founded in 1670 and served as a privateering base for the British, who renamed it Nassau in 1695, a year after it was raided by the Spanish. Both Nassau and Port Royal were infamous pirate dens even during their early days, with contemporary reports mentioning drunkards, illegal traders, prostitutes, and general lawlessness. The situation would improve slightly in the early years of the 18th century when the local governors and other officials started to crack down on piracy, with business slowly turning to:

- slavery;

- plantation maintenance;

- legal trade;

- and other venues.

Interestingly, no less than three early pirate bases were founded thousands of miles away from the Caribbean off the southeastern coast of Africa — more specifically, on the island of Madagascar. The northeastern part of the island housed two such bases, those being Ranter Bay (modern-day Rantabe) and the island of Île Sainte-Marie, while the third base, the former Fort Dauphin (modern-day Tôlanaro), was located in the southeast. Madagascar’s pirate bases were strategically located thanks to the continuous trade between the Europeans and the South and Southeast Asians. All sea routes had to go around the south of Africa, and aside from Madagascar, there were few landmasses within the Indian Ocean where traders could dock their ships. Furthermore, ships from the Middle East and the Mughal Empire would often trade in the waters of the Red Sea, which was right between Africa and Asia and north of Madagascar. These routes proved to be a wealthy source of potential booty for pirates, and indeed more than a few famous pirate raids took place in these waters.

However, Madagascar is also important in pirate lore for a different set of reasons. Namely, despite not having its own Brethren of the Coast like the Caribbean, it did house a few territories that would inspire the existence of the so-called Libertatia, or the Republic of Pirates. As we will see, some of the pirates who made their stay on Madagascar did go on to influence the local people into engaging in skirmishes and even full-on wars, with a few of the seafarers even going as far as to declare themselves kings. However, these events did not last long, and the influence of piracy more or less waned on the island within a few decades after the Golden Age.

Rise of Piracy: Prominent Pirates and Their Exploits

With the Golden Age encompassing three-fourths of a century, it had no shortage of well-known pirates, and their exploits would become legendary even in their own time. However, historians run into a few problems when it comes to exploring the subject of piracy. First and foremost, the contemporary records on these brigands are scarce; they are often quite barren and lacking in substance, and more often than not, they would be one-sided or even full of fiction. We will focus on the mythical image of the pirate in the later chapters, but for now, let’s focus on the problem of «pinning down» the prominent sea bandits of the era. As stated, most of what we know from these pirates comes from criminal records of the era, as well as local news sources, naval reports, and the scant diaries and journals found aboard some of these vessels. In addition, locating the remains of these men is often an exercise in futility considering how many of them died at sea. Furthermore, it’s difficult to locate some of their original ships due to the same problem; if a ship was decommissioned at the time, it would either be broken down for scrap parts or sunk to the bottom of the ocean. A rather large number of such pirate ships was actually located and extracted from the ocean for research, but such efforts are rare, expensive, and still don’t provide a complete picture of what pirates might have been like.

In order to best cover the entire Golden Age, it’s best to break it down period by period, covering some of the most prominent names that sailed the high seas and robbed wealthy ships of their precious cargo. The list will overwhelmingly deal with English pirates since they were the most prominent brigands at sea during this period. However, it will also go over several key individuals from contemporary France and the Netherlands, mostly ones active during the earliest part of the Golden Age.

The Buccaneering Period (1650-1680)

The 1650s were a time of turmoil and unease for Europe. While the major maritime powers were at peace, there was still a lot of friction between Catholic Spain and the increasingly Protestant countries like England, France, and the Netherlands. Eager to deal with the local non-Hispanic populace, the Spanish began to invade many islands in the Caribbean in an attempt to force the foreigners out. Hispaniola’s French population of hunters, who were at the time called buccaneers, had to flee and establish a base on the small island of Tortuga. By the time the 1650s rolled in, these former hunters and meat smokers were already actively attacking Spanish galleons and making life a living hell for them, with the first supposed attacker to do this being a French sailor called Pierre le Grand. The adjective «supposed» needs to be stressed, as only a single source mentions this pirate by name, and he is not found anywhere else in historical records of the time. Consequently, the man who would reference this buccaneer was a buccaneer and a seafarer himself, one Alexandre Exquemelin. Though he is extremely important for this particular period of the Golden Age of Piracy, we will be covering him in a later chapter.

Up until the 1680s rolled in, the buccaneers were not only raising hell in the Caribbean, but they also found themselves invading and plundering the coastal and continental cities in Central and South America. In fact, they would often invade the same cities multiple times, often with brutal and bloody results. The number of buccaneers only increased with the English capture of Jamaica in 1655. Interestingly enough, the original mission that Oliver Cromwell gave the two English commanders, Admiral William Penn and General Robert Venables, was to lead a surprise attack on the Spanish territories in the Caribbean, which the two men failed at spectacularly. Them capturing Jamaica was, in reality, more of an afterthought, and when the two men returned to England to report on their failures, Cromwell had them both imprisoned. However, the capture of Jamaica proved to be a step in the right direction; fifteen years later, Spain would officially cede the island to the English Crown, thus allowing both legal and illegal enterprises on the island to flourish.

As early as the 1660s, both the English governors of Jamaica at Port Royal and the French governors at Tortuga would provide letters of marque to both ex- and current buccaneers. With this documentation, the seafarers had legal backing when it came to raiding Spanish ships, though this didn’t necessarily prevent them from raiding crafts of their country or its allies. The buccaneers of the time had set certain trends that would become common practice with the pirates who followed, and in terms of sheer gruesomeness or boldness, it’s incredibly difficult to differentiate which generation of pirates was worse. So, it would be instructive to take a look at some of these pirates and what made them stand out.

Sir Christopher Myngs

A vice admiral with a successful career, Sir Christopher Myngs was a complex individual with an incredible life. As early as the 1650s, he was already in the Caribbean, attacking Spanish vessels and raking in a decent amount of booty. Even in these early days, Myngs was earning his infamy as a cruel, brutal commander who encouraged his men to rape and pillage as often as possible during each raid. But more importantly, Myngs had developed a questionable yet undeniably effective practice of hiring buccaneers and commanding large fleets of ships. With these men of ill-repute as his allies, Myngs successfully sacked several important cities on the South American continent, including regions of New Granada (modern-day Colombia), such as:

- Tolú and Santa Maria;

- and the cities of Cumaná;

- Puerto Cabello;

- and Coro.

He conducted this last series of raids in 1659.

The Spanish urged Cromwell’s government to do something about Myngs, and while the English paid no heed to the Spanish pleas, Myngs would see some form of justice the same year he managed to sack three key Spanish settlements. Namely, the Jamaican governor at the time, Edward D’Oyley, urged the captain not to share his loot from the raids with the buccaneers, which Myngs ignored. Over a quarter of a million pounds went to the pirates who helped Myngs with his efforts, a hefty sum that the officials deemed worthy of an embezzlement charge. Myngs was arrested and sent to England for trial, but with Cromwell dead and the Restoration taking place, he was pardoned and offered a position as a naval officer again. Late 1662 saw him back in the Caribbean, and while the English and the Spanish were no longer at war, he was still allowed to plunder Spanish ships, which he intended to do on a grander scale than before.

Thanks to the efforts and encouragement of the new governor of Jamaica, Thomas Hickman-Windsor, 1st Earl of Plymouth (better known as Lord Windsor), Myngs was employing buccaneers left and right, promising them infinite Spanish plunder. With his new seafaring soldiers, he sacked Santiago de Cuba, the biggest city of Cuba, and took control of it. And while this was a feat worthy of praise, especially considering how strong the Spanish defenses were, it would be his next feat the following year (1663) that would cement his name as a legend among buccaneers. During that year, Myngs assembled a massive fleet of 14 ships, which collectively held over 1 400 buccaneers of various national origins. At the time, this was easily the biggest pirate fleet ever assembled, and Myngs did it with an express purpose. In February of 1663, his fleet attacked and sacked Campeche, leaving behind a massive trail of devastation and ruin. Myngs himself was badly wounded during the attack, so he left the command to the Dutch corsair Edward Mansvelt as he retreated for a much-needed recovery. By 1664, Myngs was already back in England, his wounds healing.

The last two years of Myngs’s life actually saw him receive the position of vice admiral and a subsequent knighthood for his services in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Sadly, he would not see the end of this war, as he died in action during the Four Days’ Battle, which took place between June 1st and June 4th, 1666.

Myngs’s story is admittedly astounding, though it pales in comparisons to the vast majority of the other pirates represented in the passages that follow. However, his life is vital for the story of the Golden Age of Piracy for two important reasons. First and foremost, the fact that he was knighted and received a high naval position shows that pirates could sometimes manage to leave their past behind and continue their lives as, more or less, law-abiding citizens. In that regard, however, Myngs is a rarity, considering that the average pirate’s fate was death. The other major reason behind Myngs’s importance is his willingness to employ and encourage buccaneers. During his more famous raids, sacks, plunders, and attacks, some of the most famous pirate captains and buccaneers came to prominence, and he was arguably the biggest influence on the early Golden Age pirates to increase their area of operations.

Henry Morgan

To anyone who has tasted the famous Captain Morgan rum, the naming of this beverage should be no surprise, nor should the rather flamboyant and larger-than-life image of a pirate adorning the drink. This rum was, after all, named in honor of one of the most famous buccaneers of the early Golden Age of Piracy. Arguably, the man known as Henry Morgan might be the first-ever archetypal pirate «superstar» and the first person in the illegal trade to achieve both instant infamy and widespread popularity, even during his own time.

Henry Morgan was a Welsh sailor born sometime in 1635. It’s still not known how he made it to the Caribbean, but early accounts suggest that he served under Sir Christopher Myngs shortly before the sack of Campeche. He would also serve under Edward Mansfield, a seasoned privateer who had the backing of Sir Thomas Modyford, the governor of Jamaica in 1664 and the man who would provide Morgan with the letter of marque and instructions to attack Spanish settlements. (Ironically, Modyford was appointed governor with the task of reining in piratical, privateering, and buccaneering activity, and initially, he was incredibly strict and brutal in this practice but more or less completely flipped on the issue soon after.) Of course, Modyford would not be the first governor to support Morgan in his endeavors. In fact, Modyford’s predecessor was none other than Edward Morgan, Henry’s uncle and the father of Henry’s cousin and future wife, Mary. These connections gave Henry Morgan unlimited access to local resources and support in his future privateering endeavors. Interestingly enough, Edward Morgan would go on to conquer the Dutch-held islands of Sint Eustatius and Saba in 1665; he would die in December of that same year. The control of these two islands went to yet another Morgan; this time, it was Henry’s cousin and Edward’s other nephew, Thomas.

Henry Morgan made use of these connections well. His first major successes were the invasions of Puerto Principe and Porto Bello, modern-day Cuba and Panama, respectively. His letter of marque, however, did not allow him to attack people on land, only at sea. He circumvented this rule by letting Modyford know that the Spanish were planning a future invasion of English lands in the Caribbean and that his own attacks were preemptive in nature. The 1668 invasion of Porto Bello, in particular, was a stunning affair. Morgan achieved this feat by having his men paddle several miles on twenty-three small canoes and invade the city at dawn. While there were some casualties, Porto Bello was taken rather quickly, and Morgan immediately held it for ransom, demanding 350 000 pesos from the president of Panama, Don Agustin. The president tried to recapture the city, but having failed in his endeavor, he resorted to bargaining with Morgan and renegotiating the ransom down to 100 000 pesos. Of course, Morgan had plundered the city dry by that point, taking anywhere between £75 000 and £100 000 of both money and goods to Modyford in Port Royal. Having overstepped the boundaries of his letter of marque, Morgan was reprimanded by Modyford, with the governor even writing to King Charles II letting him know of Morgan’s disreputable ways. However, the English public, both in Jamaica and back home in London, hailed Morgan as a hero.

Morgan would go on to attack two settlements on Lake Maracaibo in modern-day Venezuela, those being the towns of Maracaibo and La Ceiba (modern-day Gibraltar, not to be confused with Gibraltar in Europe). The events at both Maracaibo and Gibraltar saw Morgan and his men enter and ransack an empty city, invade another city, retreat due to the Spanish counterattack back at Maracaibo, negotiate a retreat with no result, and then attack and utterly beat the Spanish. And to add insult to injury, he escaped back to Port Royal with the loot from both cities and the ravaged Spanish fleet. Unfortunately, King Charles II’s government would move on with a pro-Spanish stance in the late 1660s, which prompted Modyford to admonish Morgan for his acts but not arrest him outright.

What followed was probably Henry Morgan’s most infamous sacking of a city: the partially successful sack of Panama, which took place between 1669 and 1672. Once again, Morgan proved himself a master tactician, using guerilla methods and the element of surprise to invade the city. In order to leave no corner unturned, Morgan assembled as many as thirty ships and one thousand men – a massive fleet that outdid even his former employer, Sir Christopher Myngs. The result was a massive rout, with only about fifteen privateers dying compared to at least four hundred Spanish men. However, Morgan would not enjoy the spoils of war as he intended. Following the orders of Panama’s governor, most of the city’s wealth was burned in a massive fire caused by an explosion from hidden caches of gunpowder. A huge portion of wealth was also hauled away by ships out of the city. Morgan took off with what was left, which was still not a small sum at the time, but it was far lower than what the privateers had been expecting from a city as big as Panama.

As was the case with his previous raids, Morgan was accused of torture and other crimes, as well as retaining most of the loot and not providing the allotted share to the Crown. He was arrested alongside Modyford and sent to England in 1672, but as soon as he touched English soil, he was hailed as a hero and even knighted. Morgan would go back to Jamaica in 1675 and live out his days as a plantation owner until his death on August 25th, 1688. He would be actively involved in Jamaican politics, even serving as the governor of the island on three separate occasions.

Interestingly, Henry Morgan, though being the epitome of a pirate in the early Golden Age, vehemently refused to be addressed as such. He was a privateer, and according to his own words, he vehemently hated pirates, buccaneers, and the like. He even publicly refuted most of the accusations that were levied against him, especially ones that referred to his supposed torture of locals, misuse of nuns and other religious figures during his raid of Porto Bello, and embezzling money after each raid. In fact, Alexandre Exquemelin, who wrote about the Welsh privateer, lost a very public lawsuit, and publishers were forced to retract some of the information from future printings of Exquemelin’s works. But no matter what Henry Morgan called himself, he was far from a clean privateer who stuck to his letter of marque.

David Marteen

David Marteen was a Dutch privateer, and he was known as one of the people who willingly joined Henry Morgan in his raid of Spanish settlements in Central and South America, collectively known as the Spanish Main. Taking a contingent of men in 1664, Marteen sacked Villa Hermosa (modern Villahermosa) in the Tabasco province in a surprise raid after having marched fifty miles inland to do so. Upon his return, he had to face the Spanish patrol and retake the ships they had captured. His raids continued in Central America after this incident, with the sack of the city of Granada, Nicaragua, being the last one before Marteen departed in 1665. In the coming years, he would serve Governor Modyford as a privateer, a career he continued even under Modyford’s successor, Governor Thomas Lynch.

Marteen is not particularly famous for his raids, brutality, or eccentricity, unlike many of the other pirates covered in this volume. However, he is significant to overall pirate lore and history as being one of the first men at sea who was rumored to have buried his valuables, thus creating the legend of the so-called «buried pirate treasure». Supposedly, Marteen set up camp near Salmon Brook in modern-day Connecticut, United States, sometime in 1655, a little after raiding the Spanish galleon Neptune. However, the locals did not appreciate the pirate’s presence there, so he and his crew sailed away, burying vast amounts of their wealth at the spot. Other sources even claim that Marteen’s men established a full-fledged settlement that was wiped out more than two decades later. However, nothing in the historical records suggests an event like this happened, and Marteen probably never even sailed anywhere close to Connecticut.

Laurens de Graaf

Laurens de Graaf was a Dutch privateer who spent most of his life in the service of the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). His early life is somewhat obscure, with the most likely account being that he was sold into slavery and worked on a plantation in the Canary Islands. He somehow escaped his capture, married his French-born wife in 1674, then moved to the Caribbean and started as a privateer in the service of the French soon after. In fact, there are even some records of him helping a raid of Campeche in 1672, two years before his marriage and well before he made the Caribbean his permanent place of residence. During the late 1670s, he managed to capture a large number of ships, each larger than the last, and converted all of their crews to piracy. His biggest early success was capturing a Spanish frigate from the imposing Armada de Barlovento (a huge Spanish force of fifty ships that had the task of overseeing Spanish American territories and protecting them from advances of other nations) in 1679. By the early 1680s, he had become so prominent that Henry Morgan himself, during one of his stints as a governor, sent a pirate-hunting frigate after him.

De Graaf’s career in piracy, however, had only just begun. The Spanish decided to take vengeance for their armada’s defeat and the loss of a ship, but de Graaf took them head-on and defeated them after a prolonged sea battle. Soon enough, he would ally himself, albeit reluctantly, with another Dutch privateer, Nicholas van Hoorn. The two men forged a plan to sack the city of Veracruz (in modern-day Mexico). Their plan came to fruition on May 17th, 1683. However, the two men would end up in a massive quarrel not long after. With the Spanish fleet appearing to help the people of Veracruz, de Graaf and van Hoorn retreated to a nearby island called Isla de Sacrificios with the hostages. There, they shared the spoils and waited for the ransom on the hostages to be paid out. However, van Hoorn grew impatient and executed multiple hostages, sending their heads to the Spanish as a consequence of not receiving the ransom on time. This act infuriated de Graaf, who was by no means an angel (in fact, the Spanish would see de Graaf as the Devil incarnate), but he was firmly against the mistreatment of hostages. The two supposedly fought a duel over the matter, and while no man died, van Hoorn was wounded. His wound would soon fester and grow gangrenous, and he died not long after.

This willingness to treat the hostages well was not new behavior for de Graaf, and he would exhibit it again when his men wanted to tear into their prisoners during the Dutch privateer’s second sack of Campeche in 1685. He would go on to fight the Spanish for a few more years, leading attacks in Cuba, but at some point, he also started going after English ships. He remarried, in the meantime, to a female buccaneer called Anne Dieu-le-Veut. Around 1695, the English launched counter-offensives on de Graaf, beating his fleet and capturing his family after an attack on Port-de-Paix in Saint-Domingue. De Graaf’s later whereabouts are a mystery to historians, with one plausible outcome being that he died in Louisiana while helping to establish a French colony there.

De Graaf’s life, much like Marteen’s, doesn’t seem too important on the face of it when we compare it to other pirates who came after him. However, his naval battle against the Spanish would inspire the long-standing trope of massive pirate naval battles with swords, musket fire, and huge cannonades. Like most things regarding the subject of pirates, the idea of naval battles was blown out of proportion, and de Graaf’s skirmish with the armada was the exception, not the rule. But de Graaf also inspired another pirate myth, that of honorable pirate duels. While dueling was generally seen as a way to settle the score, it was nowhere near as dramatic or impressive as the one between de Graaf and van Hoorn. In fact, it was rare for two pirate captains to go at it; the majority of said pirate duels happened between regular sailors, mostly over sharing the spoils of a raid.

Nicholas van Hoorn

As we saw earlier, Nicholas van Hoorn would inevitably die due to the consequences of his duel with Laurens de Graaf. And indeed, the previous attack on Veracruz was the highlight of his career. However, it was merely the crowning moment of what were decades of successful seafaring notoriety, both as a privateer and as an outright pirate.

Van Hoorn was, at first, enlisted in the service of France, attacking both Dutch and Spanish ships, but he would soon turn on his own masters and go after French ships as well. In fact, van Hoorn was so infamous yet so effective that all three countries would employ his services at one point or another. During the early 1680s, he was known for plundering the west coast of African in search of slaves. His escapades became well known in the Caribbean, and the English were on his tail, though nothing came of their pursuits. Van Hoorn would soon reach the French part of Hispaniola and gain a letter of marque from its governor, enabling him to go after the Spanish settlements – an endeavor that ultimately led to the sacking of Veracruz and his famous episode with Laurens de Graaf.

In terms of infamy, van Hoorn was far from benevolent. Considering that he was capable of turning against his employers if a better opportunity arose, he was one of those contemporary pirates who perfectly fit the stereotypical depiction of a buccaneer. He was, however, far from being one of the worst to emerge during this era.

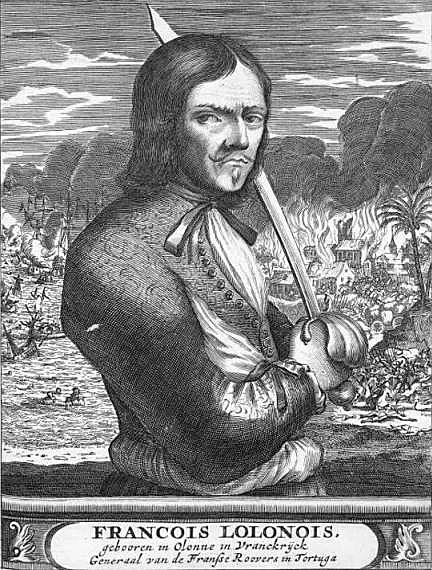

François L’Olonnais

Millions of people worldwide are aware of a particular Japanese manga called One Piece. Since its inception, this story of Monkey D. Luffy and his fellow pirates has sold close to five hundred million volumes, and it’s still an ongoing series and a huge media empire. Sharp-eyed fans will, of course, know about one particular member of the One Piece cast, a particularly rugged, manly, dangerous sword-wielder named Roronoa Zoro. What most fans probably don’t know is that he was the only member of Luffy’s crew who was named after a real-life pirate, a buccaneer who is arguably far more gruesome and deadly than his manga counterpart.

François L’Olonnais, whose real name is Jean-David Nau, was most likely born in the small French town of Les Sables-d’Olonne (hence his nom de guerre, «the Frenchman of Olonne») and was sold as an indentured servant in the Caribbean early in his life. After his servitude expired in 1660, he began sailing around the Caribbean islands until finally settling in Saint-Domingue, where he became a buccaneer. The most fateful event of this period was when L’Olonnais shipwrecked near Campeche around 1661 or 1662, which was followed by the Spanish massacring his entire crew. He survived by supposedly covering himself in blood and hiding among the dead. Once he managed to depart Campeche, he settled in Tortuga. Not long after, he held a Spanish town hostage with a group of other buccaneers. Once the Spanish sent out a ship to deal with him, he ordered every single crew member to be beheaded save for one. That one man was to relay a message to the Spanish authorities, which more than explained L’Olonnais’s raison d’être from that point forward – «I shall never henceforward give quarter to any Spaniard whatsoever».

True to his word, L’Olonnais would go on many raiding parties against the Spanish in the Caribbean and the surrounding continental lands. His most famed raid was the ransacking of Maracaibo, modern-day Venezuela, in 1666. The rape of this city took place over a few months, with L’Olonnais and his men torturing, raping, and killing its inhabitants with cruel and brutal proficiency. His next target was Gibraltar, and despite the city’s protection by a Spanish force that greatly outnumbered the buccaneers, L’Olonnais managed to beat them and hold the city for ransom. Despite getting said ransom, the French pirate still looted the city, and the inhabitants were left in a state of utter chaos. News of L’Olonnais’s brutality quickly spread throughout the Caribbean, and he was aptly dubbed the «Bane of Spain».

However, his most brutal reported act (if it really happened since there’s only one source mentioning it) came to pass when L’Olonnais and his men were pillaging through what is now modern-day Honduras. After raiding the city of Puerto Cavallo and moving onto San Pedro, the buccaneers were ambushed by the Spanish and only barely managed to escape. L’Olonnais took two Spanish prisoners with him, and while he was interrogating them for a safe, clear route to San Pedro, he cut open one of them, tore his heart out, and gnawed at it right in front of everyone’s eyes.

His subsequent exploits saw him attacking other Spanish-held cities, such as Campeche, Guatemala, and San Pedro Sula, and he even managed to sail to Jamaica and sell one of his old ships to a fellow buccaneer. Interestingly, L’Olonnais’s death came not at the hands of the Spanish but of native tribes that lived in Central America. Somewhere in modern-day Panama, L’Olonnais and his men were captured by the Darién in 1669, and those natives were, in turn, captured by the Kuna. The Kuna actually killed L’Olonnais and, according to scarce sources, dismembered his body and burned the remains.

Few men were as feared as François L’Olonnais, and if there’s one thing that his life proves without a shadow of a doubt, it’s that an effective pirate captain who wanted to maintain his position needed to have either immense charisma, perfect leadership skills, or the ability to terrify everyone on board beyond belief. This point will become relevant later when we cover the everyday life of pirates during the Golden Age.

Roche Braziliano

As stated earlier, François L’Olonnais managed to sail all the way to Jamaica and sell one of his old ships to a fellow buccaneer. It just so happened that this buccaneer, a Dutchman whose real name is still a matter of historical debate, shared a lot of the same traits as his French counterpart, and though his career is not as well-known as that of L’Olonnais, he has nonetheless remained one of the most brutal Dutch pirates of the early Golden Age.

The man known as Roche Braziliano (with many alternative spellings; consequently, the lack of a single proper spelling for pirate names was common during the Golden Age, nor was taking up pseudonyms) was an exile living in Brazil, parts of which were controlled by the Dutch at the time.

Braziliano started his privateering career there, soon moving to the Caribbean and capturing scores of ships. During his activities in the West Indies, he was captured, arrested, and sent to Spain. Upon his escape, he swore that he would end his enemies, sharing the same burning hatred for the Spanish as the man from whom he would later buy a ship.

With his new ship, Braziliano was ready to do some raiding, and throughout the 1660s, he would sail under the command of none other than Henry Morgan during one of his many raids into the Spanish Main. Much like L’Olonnais, Braziliano enjoyed torturing his captives, with one brutal example being him roasting Spaniards alive over an open fire. Braziliano was also known to be a loud, obnoxious drunk who was willing to kill a man who wouldn’t drink with him. His booming buccaneering career, however, ended somewhat abruptly after 1671, as all traces of his activities disappear. Braziliano shared his cruelty with L’Olonnais, and that’s what initially made him infamous. However, his real claim to legacy is his drunkenness. It is a well-known stereotype that pirates love to get drunk both on and off duty, and indeed, it was one stereotype that held true in the vast majority of cases, with some notable exceptions. Of all the recorded pirates in the early Golden Age, Braziliano was certainly the biggest drunkard and quite possibly even the proudest of that fact.

The Pirate Round Period (the 1690s)

As the 17th century was nearing its end, the major maritime forces increased their efforts in reducing piracy in the Caribbean. Furthermore, with the Glorious Revolution of 1688 taking place and William of Orange taking the throne of England, the country renewed its hostilities with France and its eccentric king, Louis XIV. And while that topic is fascinating in and of itself, it’s merely the backdrop behind the first collapse of the buccaneering period of the Golden Age. Namely, the Brethren of the Coast was an international crew of people, and once hostilities between England and France reignited, the men simply refused to collaborate with one another. In other words, gone were the days when Henry Morgan could lead a raid with dozens of ships sailing under many different colors. Furthermore, the cities in the Spanish Main and on the islands were drained of their resources. Piracy did continue, but the sea brigands needed a new, fresh pool of resources. And they did, indeed, find one, hundreds of miles away, near the eastern shores of Africa.

There was no better time to sail the Indian Ocean than the 1690s. The Indian subcontinent and the surrounding lands were laden with resources that Europeans craved at the time, such as:

- silk;

- calico;

- tea;

- spices;

- and even art.

Furthermore, South and Southeast Asia housed several dozens of factories from a few East India companies from Europe, and the ships coming and going to these factories would often carry valuables on board and even years’ worth of wages for each factory worker. And considering how thinly the European maritime forces were spread at the time, policing these waters was a task doomed to fail, as everyone, from a small fishing boat to a huge trading galleon, was a target for pirates. And it didn’t just stop with European ships. Vessels sent out by the Great Moghul would also find themselves on the pirates’ radar, and considering the vast wealth of the Moghuls, plundering their vessels would be quite lucrative. That’s why European pirates also found themselves in the Red Sea, which was a popular trading spot for both the Mughal Empire and the local Muslim merchants (either Arabian or Ottoman).

The lengthy route that the pirates would take from either the Caribbean or Europe to the Indian subcontinent had a fitting name: the Pirate Round. And while the period of the Pirate Round was the briefest of all three that encompass the Golden Age, it was probably more significant than the buccaneering period. After all, it was the pirates who made up this period that showed the world just how alluring, engaging, and profitable the pirate trade could be. But more importantly, it helped put piracy on the map as an issue the major powers could no longer ignore.

Thomas Tew

Thomas Tew, an English seafarer born somewhere in the American colonies, might not have had a career that involved countless voyages and city sackings like his buccaneering predecessors did. In fact, he only made two significant pirate cruises in his entire life. However, not only was he successful in being a pirate, but he was also arguably the progenitor of the Pirate Round, as he was the first pirate to show the immense possibilities of sailing east rather than west.

Tew began his career in the early 1690s in Bermuda, where he had obtained a letter of marque to go after French settlements in the current-day Republic of The Gambia in West Africa. However, shortly after sailing on this journey, Tew openly declared to his crew that he wanted to turn to piracy. According to reports, his crew accepted this change of pace with open arms, and his ship, the Amity, set sail for the Red Sea.

Once there, Tew and his men attacked a rather large dhow (a type of single or multiple mast ship common in that region; the particular dhow that Tew went after was a ghanjah), and he did so with no casualties on either side; the dhow crew simply surrendered. Tew’s plunder was massive, with his own share of the loot being valued at anywhere between £5 000 and £8 000 in contemporary currency. He and his men divided the plunder when they docked at Madagascar to careen the ship (flip it on the side during the low tide for necessary repairs) before sailing onward to New York. Interestingly, they docked in Île Sainte-Marie, where Adam Baldridge (another pirate who will be covered later on) had built a sturdy fort and hosted numerous pirates over the years.

Back after his first successful pirate run, Tew became close friends with Benjamin Fletcher, the governor of New York. He would finance another of Tew’s expeditions in 1694. Tew was back at the mouth of the Red Sea, but this time, he found it swarming with other notable pirates. His story, it seems, had become widespread, so everyone wanted a piece of the new Pirate Round. Tew, among many other captains, decided to sail under another famed seafarer at the time, Henry Every. Tew’s ship actually attacked a vessel from a powerful Mughal convoy, with Tew believing that they were going after the famous Fateh Muhammed, a particularly wealthy ship with bountiful plunder. However, during the skirmish, Tew lost his life. However, the story doesn’t end there. His men, demoralized after his death, surrendered to the Mughal forces, though they would later be rescued by none other than Henry Every during his own successes over the Muslim ships. One of Tew’s crew members, a pirate known as John Ireland, took the Amity to Baldridge’s pirate safe haven to have the ship refitted. Both Thomas Tew and John Ireland had been targets of Capitan Kidd and Buried TreasureCaptain William Kidd, at least according to the commission he had received from King William III.

Thomas Tew was undoubtedly important for pioneering the Pirate Round cruises and plunders, and though he did not enjoy the fruits of his crew’s final plunder, he was nonetheless effective throughout his life. Furthermore, Tew became the source of another famous pirate myth, that of a seafarer getting involved with a native woman of royalty and producing offspring. According to legend, Tew had an affair with a Malagasy princess, and as a result, his son, Ratsimilaho, was born. The boy would use this supposed familial connection to rule over a large region in the island known as the Betsimisaraka confederation. Of course, it’s unknown if Ratsimilaho was actually the son of a pirate and a queen, and even if he was, only the first name of the pirate is given, that being «Thomas». Considering how common of a name that was in contemporary England, his piratical father could have been anyone, Tew included. Of course, pirates and native Malagasy women often intermarried and interbred, so it wasn’t all that rare for their offspring to play prominent roles in Malagasy sociopolitical events.

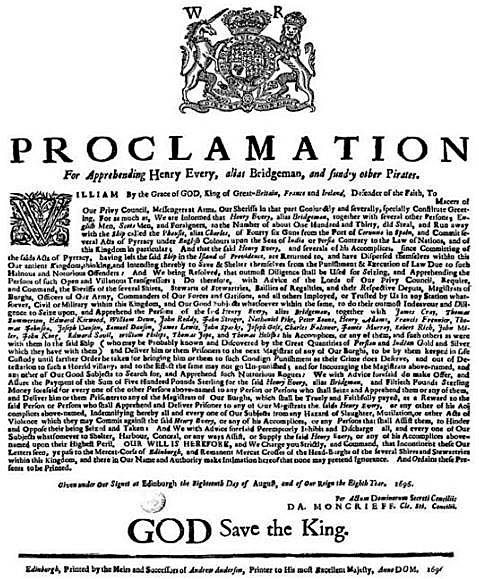

Henry Every

Western history gained its first «Arch Pirate» in 1694. This man would only be an active pirate for roughly two years, but he still achieved the seemingly impossible: he acquired a massive amount of wealth from a huge raid of important Mughal ships and managed to escape justice unscathed. If Thomas Tew inspired people to turn pirate and rob the ships in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, the honor of catapulting piracy into the stuff of legends belonged to none other than a clean-shaven, stocky, pale-faced man of a medium, unimposing height with piercing cold eyes: Henry Every.

Every’s birthplace was most likely a village in England known as Newton Ferrers, some distance away from Plymouth. Based on his skills, it’s likely that he had seafaring experiences at a fairly young age. Some legends claim that he fought in the waters around Algiers and Campeche and around the Caribbean in the 1670s, but none of that can be substantiated by historical evidence. The earliest record we have of Every’s activities was during the Nine Years’ War between France and England. Every was a midshipman on the HMS Rupert in his early thirties; by this time, he was already married with a family to support. In 1690, he participated in various battles, including the infamous Battle of Beachy Head. Soon after, he was discharged from the navy. Following his discharge, Every began his early illegal enterprises, sailing as an interloper (i. e., an unlicensed slaver). He had the sneaky habit of capturing both the slaves and their former slaveowners.

In 1694, Every’s inevitable turn to piracy took place when he was elected as the first mate of Charles II, one of four ships that were part of the so-called Spanish Expedition Shipping venture. The venture’s goal was to expand trade with the Spanish and prey on the French ships in the Caribbean. However, due to a series of misfortunes and due to Charles II’s Captain Gibson being an unreliable drunk, the men soon started to talk about mutiny. Every spearheaded the movement, and the men indeed mutinied and marooned Gibson onshore, taking Charles II and renaming it the Fancy. Unsurprisingly, Every was elected captain of the ship.

Every began his piratical career in Cape Verde, attacking three English merchant ships and recruiting some men to his crew. After a few brief stints on the Guinea coast and at Benin, where he had his ship fitted to sail faster, Every moved to the island of Principe, where he captured two Danish privateers and added more men to his crew. Near the Comoro Islands, specifically the island of Johanna, Every captured a French pirate ship, looted it, and recruited more men, with his force now rounding up to a neat 150 men. But this was all merely preparation for his biggest success to date, if not the single biggest success in the history of the Golden Age of Piracy. Entering the Mandab Strait (modern-day Bab-el-Mandeb) into the Red Sea, Every ran into five other pirate captains:

- Richard Want;

- William Mayes;

- Joseph Faro;

- Thomas Wake;

- and the aforementioned Thomas Tew.

The men agreed to unite their ships into a massive fleet, with Every as the admiral, in order to capture a convoy of twenty-five Mughal ships. The two biggest ships of the empire were part of the convoy, with the 600-ton Fateh Muhammed (the one Tew lost his life and crew to) being the escort to a far larger, far fiercer ship that was the pride and joy of the Great Moghul:

- the 1 600-ton;

- 80-cannon strong Ganj-i-Sawai («exceeding treasure»).

After about five days of pursuit and the loss of the Amity’s crew and captain, Every managed to capture Fateh Muhammed, whose own crew gave up without any resistance. Ganj-i-Sawai, however, put up a massive resistance, which resulted in a fierce battle.

Every was incredibly lucky in at least two instances during the battle. The first instance was during his initial attack when the Fancy struck the broadside of Ganj-i-Sawai’s mainmast, damaging it significantly. His next stroke of luck came from some of the cannons on board the Mughal ship exploding, which killed or seriously injured a huge number of crew members on board. Every reportedly ordered his men to loot, rape, and pillage as ruthlessly as possible, with some of the Muslim women on board who were part of the royal entourage reportedly killing themselves by jumping overboard into the sea to avoid becoming rape victims. An unsubstantiated legend suggests that Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s own granddaughter was on board and that Every had his way with her. While most of these tales of brutality are exaggerated, there was a lot of illicit behavior aboard the captured Ganj-i-Sawai, at least according to the testimonies of Every’s crew members, who were arrested years later.

The spoils from both Ganj-i-Sawai and Fateh Muhammed made Every and his men rich beyond their wildest dreams. However, what ensued was a veritable death sentence to every single one of the pirates involved with this raid. Once the stripped Ganj-i-Sawai made its way to the Indian shores, the local governors immediately briefed Emperor Aurangzeb of the situation, and they imprisoned the English East India Company (EIC) factors in the meantime. Beside himself with absolute rage, Aurangzeb forced the closures of four separate EIC factories and put their officers behind bars. He almost went as far as to attack the English-controlled city of Bombay.

Both British Parliament and the EIC had to find a way to appease the Great Moghul since their East Indian trade quite literally depended on his good spirits. As such, an award of £500, later to be doubled at £1 000, was offered for the capture of Henry Every, thus beginning the first-ever worldwide manhunt in history. And fate would have it that this manhunt ended in failure; after 1696, there are no reliable records of Henry Every’s activities anywhere. There were some rumors that he either spent the rest of his days in Madagascar, lived in England alongside the Great Moghul’s granddaughter, or wasted away in the English countryside, dying destitute. Whatever the case may be, one thing is for sure – Every remains one of the few pirates to have completely escaped facing justice and paying for his crimes, thus cementing him as the «Arch Pirate».

The historical importance of Henry Every cannot be overstated. And like many other pirates, he also pioneered, or rather improved upon, the trend of using false names and aliases. To many crews on the open sea, he was known either as:

- John or Jack Avery;

- Benjamin Bridgeman;

- or Long Ben.

This last alias, in particular, was a favorite of his crew and associates.

William Kidd

Most of the famed pirates became involved with the practice willingly, mostly out of necessity. Of course, as we will see later, a few did so out of a sense of adventure and even took pride in being sea brigands. However, it was (and still is) incredibly difficult to find someone who became a pirate by way of an odd cosmic coincidence. It’s also rare to have an infamous, influential pirate who vehemently refused to be referred to as one.