Among the Titanic survivors, one of the most notable figures was Molly Brown, famously dubbed the «Unsinkable Molly Brown». A wealthy American socialite, she played a crucial role during the chaos of the sinking by helping other passengers into lifeboats and encouraging the crew to return to search for survivors. Despite her efforts, she was unable to save everyone, but her bravery and resilience made her a symbol of courage in the face of disaster. Brown survived in Lifeboat 6 and later became an enduring symbol of strength and resourcefulness.

Another remarkable survivor was Violet Jessop, a stewardess and nurse who not only survived the Titanic disaster but also faced two other maritime tragedies. Jessop was aboard the Britannic when it sank in 1916, and she had previously survived the sinking of the Olympic, a sister ship of the Titanic. Her experiences offer a unique perspective on the era’s maritime challenges, and her survival through three major shipwrecks underscores her extraordinary endurance and fortitude. Jessop’s life and experiences provide a compelling glimpse into the resilience of those who faced such unprecedented crises.

According to Captain Rostron, there were now 705 extra people aboard Carpathia: 705 individuals thankful to be alive, but 705 confused souls, mourning for lost family, friends and colleagues. Many were also physically injured, mentally exhausted and distressed about lost possessions. Their emotions were in a whirl, while for four hours Rostron made his way through the treacherous ice fields about which Titanic had been warned.

There were, of course, those who had, beyond hope, found loved ones they had thought lost. Ruth Dodge and her 4-year-old son had been in Lifeboat 5, the second one sent out. It was not until her son said that he had seen his daddy aboard Carpathia but had been playing a game by hiding from him, that she discovered her husband had reached safety in Lifeboat 13.

Equally fortunate was Nellie Becker, who was travelling with her three children. When Lifeboat 11 was loaded, 4-year-old Marion and 1-year-old Richard were placed in it, and it was declared full. Nellie screamed that she needed to be with her children, and she was allowed in, but her daughter Ruth, aged 12, was not. Ruth eventually went into Lifeboat 13, and, like the Dodges, was unexpectedly but luckily reunited with her family aboard Carpathia.

Leah Aks, a third-class passenger born in Poland and travelling to join her husband, had one of the more traumatic ordeals of those in the lifeboats. As she waited for Lifeboat 11, one of the stewards suddenly grabbed her 10-month-old baby, Frank, and literally tossed him into the boat. When Leah tried to retrieve him, she was restrained by other stewards, who thought she was attempting to push her way onto the boat. Soon thereafter, the now-distraught woman was seated in Lifeboat 13, where Selena Rogers Cook and Ruth Becker tried to comfort her. Hours later, aboard Carpathia, Leah and Selena passed a woman holding a baby, whom Leah recognized as Frank, but the woman – supposedly either Elizabeth Nye or Argene del Carlo – claimed the baby as her own. Leah and Selena went to Captain Rostron, and after Leah described a birthmark on Frank’s chest, he was returned to her.

THE TALE OF J BRUCE ISMAY No survivor was treated more harshly by the American press than J Bruce Ismay, who became the tragedy’s scapegoat. He was lambasted in editorials and cartoons for having saved himself when so many died, and William Randolph Hearst’s New York American surrounded his photo with pictures of widows of those lost, referring to him as «J Brute Ismay». The British were kinder, the inquiry finding him free of any fault, and many praising him for helping load women into boats before his own departure. Nonetheless, he remained guilt-ridden for the rest of his life.

Two children not so easily reunited with their parents were Michel and Edmond Navratil, aged three and two. As increasingly desperate people had crushed around Collapsible D in the moments before it was launched, second-class passenger Michel Hoffman had passed the two children through the stewards to the boat. But Hoffman went down with Titanic, and after Carpathia arrived in New York, the story of the two orphans was carried in newspapers around the world. Only then did it transpire that Hoffman, whose real name was Navratil, had stolen his sons from their mother – from whom he was unhappily separated – hoping she would join them all in the United States. In May, White Star Line arranged Marcelle Navratil’s passage to New York, and she was able to take her two boys back to France.

«How lucky we were to be alive and even fed. But many were very fussy & annoying & stealing was really bad. Seemed everyone lost things both the regular passengers & any who brought anything with them. Mother made dresses for Margery Collyer & me out of a blue blanket and #50 thread sewing them by hand. Kept us warm but we sure looked funny, now as I look back…The things I saw are as plain in my mind as if they were printed on my brain. Guess I was very lucky having the kind of mother I had, for she was a tower of strength to lots who were sort of falling apart and a most practical psychologist in her own way». – Bertha Watt

Another son who lost his father was 21-year-old R Norris Williams. When Premonitions of Titanic Disaster – Historical Facts of the TragedyTitanic began to go down, he and his father tried to swim away from the ship. To his amazement, Williams came face to face with Gamon de Pycombe, the awardwinning bulldog of first-class passenger Robert W Daniels, which was doing likewise. Williams’ father died when a funnel collapsed on him, but the subsequent wave helped push the son towards Collapsible A, onto which he was pulled. On Carpathia, one of the doctors recommended amputating Williams’ legs, which had been severely damaged by the cold water. Williams ignored the advice, and eventually was able to resume his tennis career.

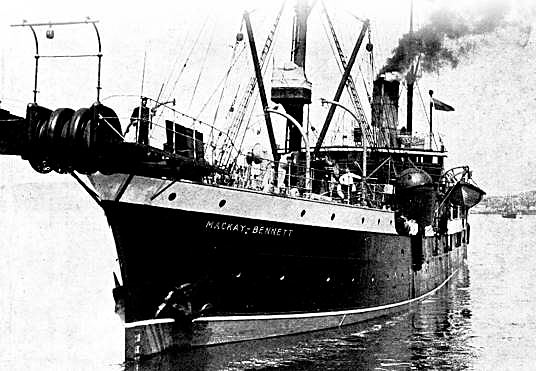

COFFINS AND CORPSES Within hours of Titanic sinking, White Star initiated an attempt to recover the bodies of those who died. On 17 April, the cable ship Mackay-Bennett left Halifax, Nova Scotia, with more than 100 coffins and several tons of ice for preserving. In a week-long search, 306 bodies were found: 116 so totally unrecognizable that they were buried at sea and 190 that were brought back to Halifax. In the following weeks three other ships found another 22 bodies. In total, 150 victims were buried in cemeteries in Halifax and 59 were claimed by relatives and buried elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the hundreds of survivors travelling aboard Carpathia endured thunderstorms, heavy rain and thick fog on the painfully slow, woeful voyage to New York. There, on 18 April, before some 30 000 onlookers, Rostron eased his ship up to the Cunard pier. From here, it was the first step for the former Titanic passengers in making a very different entrance to the New World to the one they expected.

«…soon after that, about five o’clock we saw the mast lights of the Carpathia on the horizon – & then the headlights – & then the portholes & then we knew we should be saved. We had to go up on a rope ladder on the side of the Carpathia (I don’t know how I did it), and then we were taken on board & given coffee & brandy – but as our boat was about the sixteenth or eighteenth to arrive all the berths were given away before I reached there & so I had to stay in the Library for the four days & nights before we reached New York – & there were no brushes or combs to be had – nor toothbrushes as these were all sold in a minute.» – Mary Hewlett

«At eight o’clock in the morning, a life-boat from the Titanic came to rescue us and took us on board the Carpathia where we were wonderfully taken care of. I found everyone on the dock. I find it difficult to walk, my feet being slightly bruised. Here I am settled at Harry’s place and I think that a few day’s rest will do me a lot of good. I admit that I am a little tired and you must excuse me if I end this letter here, a little abruptly.» – George Rheims

Covering an International Sensation

The loss of Titanic was one of the greatest news events of all time. Well before the survivors were even rescued, rumours about it had flashed over the wireless throughout the world. By the time Harold Cottam and Harold Bride began transmitting the list of survivors (information not immediately made available to the public), most newspaper editors had already made the assessment that any damage to the «unsinkable ship» would be an inconvenience rather than a tragedy. The Daily Mirror of London, for example, produced a headline stating «EVERYONE SAFE», while proclaiming «Helpless Giant Being Towed to Port by Allan Liner».

One newspaper, however, did not make such assumptions. It was 1:20 am on 15 April when a bulletin reporting that Titanic had struck an iceberg and was sinking at the bow reached the newsroom of The New York Times. Carr Van Anda, the managing editor, immediately made calls to correspondents in Halifax, a wireless station in Montreal that had received the news via the steamer Virginian, and officials of the White Star Line. The last had not received an update since the first wireless report. Unlike other editors, Van Anda reasoned that the terrible silence meant only one thing: it had not been possible to send more messages. He immediately reorganized the first page of the late edition, with articles about the famous people aboard, previous times ships had collided with icebergs, other vessels that had reported ice in the region, and, in a bold box, the latest news as it had come through on the wireless.

Interviewing Harold Bride Van Anda’s greatest coup was gaining an exclusive interview with Harold Bride. Wireless inventor Guglielmo Marconi planned to speak to Bride and Harold Cottam; Van Anda, who was Marconi’s good friend, persuaded him to do it aboard Carpathia and to take The New York Times reporter Jim Speers with him. Backed by a little bluster, Speers was able to board the ship with Marconi long before any other reporters. At Marconi’s request, Bride gave Speers an extended account of the disaster. The next day it appeared verbatim over five columns of the front page, and it is still considered one of the most gripping stories in newspaper history.

When the paper went to press at 3:30 am, not only did it give more background than any other newspaper, it was the only major daily newspaper to report flatly that Titanic had gone down. By the next day, businessmen, families of those aboard Titanic and the curious public all crowded outside newspaper offices, Lloyd’s at the Royal Exchange and White Star’s headquarters in London, Southampton and New York, waiting for information.

Many of the newspapers being sold on the streets still claimed that all the passengers had been saved. But the headline of The New York Times stated: «TITANIC SINKS FOUR HOURS AFTER HITTING ICEBERG; 866 RESCUED BY CARPATHIA, PROBABLY 1250 PERISH; ISMAY SAFE, MRS. ASTOR MAYBE, NOTED NAMES MISSING». By 17 April, the thorough coverage by Van Anda’s team had led to newspapers around the world lifting their material straight from The New York Times.

But Van Anda’s greatest success was still to come. With Carpathia scheduled to arrive at 9:30 pm on 18 April, this gave him only three hours to cover the biggest story in the world before the first edition went to press at 12:30 am. He hired an entire floor of a hotel near Cunard’s pier, fully staffed it with editors and installed four telephone lines directly to the rewrite desk of The New York Times. He also sent 16 reporters to cover every aspect of the story, although it had already been determined that no newspaper could have more than four passes to the pier and no one would be allowed on the ship until all survivors had left. The reporters and accompanying photographers were assigned in advance to almost every imaginable angle of the story.

Van Anda’s careful organization paid off. Friday morning’s first edition contained 15 pages (out of 24) Titanic Building and the Age of the Linerabout Titanic, including an interview with Bride that was the journalistic highlight of the entire tragedy. Almost a century later that edition is still considered a masterpiece of newspaper history. More importantly, The New York Times coverage of the disaster helped greatly to secure the reputation and financial position of a newspaper that had been struggling, and to establish it as one of the world’s key centres of journalistic innovation and excellence. Years later, when Van Anda was visiting the British press baron Lord Northcliffe, his host pulled a copy of The New York Times from 19 April 1912 out of his desk. «We keep this», he said, «as an example of the greatest accomplishment in news reporting».

«The terrible news of the sinking of the Titanic reached New York at about eleven o’clock last night and the scene on Broadway was awful. Crowds of people were coming out of the theatres, cafés were going full tilt, and autos whizzing everywhere, when the newsboys began to cry «Extra! Extra Paper! Titanic sunk with 1 800 on board!» … Nobody could realize what had happened, and when they did begin to understand, the excitement was almost enough to cause a panic in the theatres. … The scene in front of the steamship office was a tragedy in itself». – Alexander Macomb