Boat Buying Process involves several critical steps to ensure a successful purchase. First, you’ll need to master the art of negotiating, or «dickering», to make a reasonable offer that reflects the boat’s value. Once an agreement is reached, closing the sale and ensuring all terms are documented is essential; getting everything in writing protects both buyer and seller. Additionally, hiring a marine surveyor can provide crucial insights into the boat’s condition before finalizing the deal.

Financing and marine insurance are also important aspects to consider, as they directly affect ownership costs. Lastly, understanding the new boat warranty and the implications of state registration versus documentation will help you navigate the ownership landscape, including any tax considerations outlined in the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

Making an Offer

For a variety of reasons, fall is usually the best time to buy a boat, whether new or used. One reason is that it affords the time to compare prices, conduct a survey, arrange for financing, transfer registration or documentation, and get repairs arranged without interfering with use of the boat.

If the boat is new, a fall down payment may assure spring delivery, although the boat building industry is notorious for its cavalier attitude toward delivery dates. Still, builders want as much production completed and shipped by late spring as possible so that they can devote the summer to the development of new models for introduction at the fall boat shows.

Boat dealers also want fall sales. By clearing inventory they are in a position to order new models for spring sales. Moreover, the interest and other expenses they pay for a showroom boat through the winter are apt to be a straight loss, not recoverable if the boat is sold six months later.

In fact, the saving a dealer realizes from being able to get out from under the interest and insurance payments may make storing the boat until the spring an offer he can throw in at the original sale price. It is certainly worth a buyer’s bargaining for.

In the used-boat market, the savings may be even greater. Many owners want to sell so they can get a new boat; the cost of storing and maintaining the boat through the winter, as well as the need for cash for a new boat, may make the seller receptive to a lower offer.

For the buyer of a used boat, purchase at decommissioning time has all sorts of advantages. He has the winter to make modifications and repairs, replace sails more cheaply, and shop for new equipment. One example is the overhauling of an auxiliary engine, the most common item needing attention after the purchase of a used boat. Fall purchase gives time to have the engine completely overhauled, removing it for rebuilding if necessary, usually an impossible or expensive task in the middle of spring outfitting. The same principle applies to restoring the topsides with a polyurethane coating, or installing new equipment, new electronics, or increased tankage.

This is one side of the argument for buying in the fall. But what is the down side of a fall purchase? By the time a new owner has paid for insurance, storage, winterizing, and interest on financing, does he come out ahead by owning a boat that sits idle over the winter?

The answer is that he should come out ahead. The insurance premium during layout is but a fraction of that of the premium while the boat is in commission. Thus, the monthly cost of insurance should not be calculated by dividing the total annual premium by 12, but rather by dividing between layup and in-the-water rates.

Storage, too, is a cost that is highly variable. In figuring storage costs, do not lump those flat charges with spring outfitting done by the boatyard, as that work would be paid for by the buyer if he buys during the winter, or passed on by the seller if the purchase is after spring launching.

Obviously, there is no sense in buying a boat in the fall just to buy in the fall. If there is a reasonable chance that a better boat could be found by waiting, or that the price will go down, then, of course, play the waiting game.

The Refined Art of Dickering

When you have decided to make an offer on a boat, regardless of which one, you want to get it for the least money possible. The seller wants to sell it for the most money possible. There is, therefore, a special process involved in arriving at a deal. That process is known as «dickering».

We have a friend who has a simple philosophy of dickering for used boats: «Offer the seller half of what he’s asking», he says. «If the seller says no, tell him to go to hell».

This philosophy is certainly extreme, but it contains the two most important points of successful dickering. The first is: The seller of a used boat never expects to get a hundred percent of his asking price, so you should offer less. The second point is: If you really want a good price, you have to be prepared to walk away from the deal and reject the boat altogether.

There are exceptions to both these essential rules, of course. For example, there are always a number of boats that are not really «on the market», even though they appear in broker’s listings and in classified ads. Typically, an owner lists such a boat at a very high price, just in case some unwary (and not very smart) buyer comes along looking for exactly that boat. The owner does not really expect to sell the boat and would not mind keeping it indefinitely.

How Much Should You Offer? For boats that really are on the market, the key question is just exactly how much less than a hundred percent an owner will take. In classified ads, terms such as «asking» or «near offer» are plain statements that the sale price is not fixed, and terms such as «must sell» or «desperate» are open invitations to much lower offers. Terms like «firm», sometimes means the price is firm, but often the word just indicates that the seller will not take a lot less than his asking price.

It is impossible to know just how much less to offer on any boat. Our friend’s «half what he’s asking» may be generally unrealistic, but the corollary is: «If the owner says ‘yes’ to your first offer, you have offered too much». In the current used-boat market, it would be very easy to make an offer that is higher than what is necessary.

Many people are reluctant to make a very low offer, thinking that such an offer might be an insult to the owner. If you are dealing directly with the owner, however, this is a chance that is worth taking.

It is in this area of buying a used boat that a broker can be most helpful. A good broker will not only have a sense of the current marketplace (what the demand for a particular boat might be and the price range it should sell in), and he will also know or be able to find out the seller’s situation (whether the seller will slash the price to unload the boat or will hold out for top dollar).

Source: wikipedia.org

The broker’s commission, of course, depends on the selling price, so he or she will have a bit of a conflict inherent in the process. But every broker also knows that any sale is better than no sale, and they are almost always ready to make any offer you want, just to get the dickering process underway. For the broker, the first offer – along with the normal 10 percent deposit of earnest money – is the buyer’s first real commitment and the first sign that the buyer is really serious about buying a boat and worth devoting a lot of time to.

Also, the good broker usually will have an advantage in knowing the psychology of the seller – something that is very difficult for the buyer to pick up in the casual and short acquaintance typical of boat buying. For some sellers, it may be best to force the issue – give them 10 minutes to make a decision. For other sellers, that sort of pressure may be the wrong approach – it would be best to let them mull over your offer for two or three days. A good broker will have a better sense than most buyers of when to push and when to pat.

The Second Rule. The second rule, being ready to walk away from the deal, is where most used-boat buyers fail in the dickering process, since there is almost always a strain of irrationality in any boat purchase. If the buyer has fallen in love with a boat and wants it badly, the advantage is to the seller, and the threat of losing the boat can result in the buyer paying too much.

Of course, once the dickering commences, there is a major psychological game going on. If the buyer really wants the boat, he cannot let the seller know how eager he is or he will be easy pickings for the seller. At the same time, the buyer cannot act totally disinterested—he has to be cautious about the psychology of the seller. Most people develop a fondness, sometimes even a love, for their boats, and a seller may just turn adamant if he feels the buyer is not likely to care for his former love.

The key is, first, convincing yourself that you can do without the boat you are negotiating for; and second, convincing the seller that you want the boat, but can do without it unless you can get it for the right price.

When dealing through a broker, a buyer must adopt a slightly different strategy. Although brokers try to be neutral in the dickering process, they inevitably will favor one side or the other. Initially, it is most often the seller’s side, since the seller is the one who is paying the broker’s commission, and the broker will benefit from the highest selling price.

To get a good deal on a used boat, you have to swing the broker to your side – working more for you than for the seller. This will inevitably happen at the instant the broker believes you are going to walk away. At that point, the broker will begin using his selling skills on the seller, in an effort to convince the seller to take less, rather than to convince you to offer more.

Of course, unless you are an exceptionally good actor, you have to truly be willing to walk away. Take it or leave it, that’s my final offer.

Buying Through a Broker. When buying through a broker, you initiate an offer by signing a purchase agreement and putting money down—often as much as 10 percent of your offer. The purchase agreements are generally pretty standardized, with just a few variations from company to company.

The purchase agreement usually gives specifications of the boat and equipment, the price offered, and a number of conditions for the sale, such as a boat survey satisfactory to the buyer, and the availability of financing for the purchase.

There is also usually a space for «additional conditions», into which you can put anything you would like. For example, for a boat stored out of the water, you would normally add a provision that a certain amount of money – say $ 1 000 – be held in escrow in case you discover that the electronics or engine do not work when the boat is launched.

The standard agreements are written in «legalese» and can be difficult to understand. Brokers tell us that an amazing number of people sign them without reading them. Nevertheless, a 10-percent deposit is a sizable sum of money that is potentially at risk, so there is no short cut – you simply must understand what you are signing. The specific details of the sales agreement are outlined in more detail below.

At this point, it is also desirable to reread the equipment list, thinking not so much of what is on it, but of what is not on it. Every seller will take some equipment off the boat – maybe a clock that was a gift or winch handles that are usable on the next boat. If you want a piece of equipment that is on the boat, but not on the equipment list, it is best to add it to the list at the time you make the initial offer. Changing the deal is increasingly difficult the further you go in the process.

Usually, once you sign a purchase agreement, the dickering process is carried on by phone and you do not have to sign interim agreements for counteroffers and counter-counteroffers. However, some brokers will ask you to put later offers in writing, often in the form of a telegram or telex to the broker. Once a sales price is finally agreed on, you will be required to sign a final version of the sales agreement and perhaps submit an additional check so that your deposit is equal to 10 percent of the final figure.

Dealing Direct. When dealing directly with an owner, the process is usually more casual. You can make offers and counteroffers face-to-face or by phone. However, at some point in the process, it is necessary to make out a purchase agreement. It can be simple or elaborate, in plain English or in legal language. At the minimum, it should identify the buyer, the seller, the boat, and the equipment in very precise terms; specify the price; and enumerate conditions of the sale, such as a required survey and delivery dates and times.

A deposit of earnest money needs to go to the seller at the time of signing the purchase agreement. The amount needs to be substantial, but nothing like the 10 percent a broker normally requires (brokers always call for 10 percent because that is their commission). Ina private deal, the buyer and seller have to agree on the amount – a reasonable figure would be something like $ 500 on a boat under $ 20 000 and perhaps $ 1 000 on a boat up to $ 50 000, with proportionately more for more expensive boats.

The earnest money, as well as engine and electronics escrow, can be difficult to handle without a middleman, and problems can be created if either buyer or seller backs out of the deal. It is best to state very clearly how this will be handled. You usually specify that you will withhold a certain sum of money until you have seen the engines and the electronics operate, and you need to specify exactly the conditions under which the seller must return the deposit, usually within three days of an unsatisfactory survey or your failure to get financing on the boat.

If you are financing a boat, the finance company will attend to the details of the closing, including the transfer of title and the documentation. If you are paying cash, the transfer and documentation are quite straightforward – a matter of filling out several Coast Guard forms, available free from your nearest documentation office. This process is covered in more detail in the next chapter.

Unfortunately, if you are Buying and Selling Making – a Sound Investment In a New or Used Boatfinancing the boat, the finance company will probably require you to hire a documentation service. This is one of the big rip-offs in the process of buying a used boat, since anyone can complete the process, but it is several hundred dollars you will have to kiss good-bye if you finance through a marine finance company.

Closing the Sale

Get Everything in Writing

The purchase of a boat, whether new or used, requires careful consideration and should be the result of cautious deliberation and not a headlong rush into a boat dealer’s office with money in hand. The contract is all important; prior to the purchase, you must carefully put your entire agreement in writing. Your purchase agreement must clearly state:

- the total price for the boat;

- a firm date for delivery of the boat;

- a description of the condition in which delivery of the boat is to be made (which extras, options and equipment are included);

- whether the boat is to be commissioned or not;

- a statement of the nature and extent of the warranty;

- a written statement of the boat dealer’s obligation to remedy defects and how long the manufacturer will be responsible, and for what.

Your contract to purchase a new boat may be the second most important document you will ever sign. For most boat owners, their boat is second only to their house in value. Very few people would consider purchasing a home without consulting an attorney, yet the vast majority of boat owners run blindly into boat dealers’ offices with ready money to purchase boats. You might even want to have the documents drafted by an attorney rather than the dealer. While most boat dealers are honest and hard-working people, there are a few whose business reversals over the past few years have caused them to play fast and loose with customers’ money. A request for payment in advance for a boat should be looked on with great skepticism. Final payment for your new boat should not be made until you have looked over the boat carefully and had your surveyor inspect it. Hopefully, your dealer will agree to allow sea trials of the boat prior to final your payment.

Whether the boat you are buying is new or used, it is important that you receive clear and unencumbered ownership. You should communicate with your local governmental office in charge of the filing and recording of liens on real and personal property to determine if any liens have been recorded on the boat which you are buying. If you are purchasing a new boat, some of the potential liens which you must investigate are those which were occasioned by the dealer through the use of his floor plan, (the dealer’s financing which allows him to purchase boats), or liens which attach as a result of work that was done on your boat or on other boats owned by the dealer while in his possession, or as a result of either shipping or storage of your new boat.

If you are purchasing a used boat, in addition to all of the aforementioned, you must be satisfied that the person from whom you are purchasing the boat does not have any prior liens from his seller (or his seller’s predecessor). In addition, you must be very careful that your seller (or his predecessor) does not owe any money for work done on the boat, storage of the boat, or any other boatyard fees. Careful investigation prior to purchase may save you much heartache later. While state laws vary, there are mechanisms for ascertaining whether or not liens do exist in almost all instances. Use them!

Talk to a surveyor. Even a new boat should be surveyed prior to its delivery. It is much easier to obtain the cooperation of a dealer before you have paid him. Buyers should provide in the sales contract that a Buying a Boat – The Ten Minute Surveyboat should be surveyed by the surveyor of their choice prior to delivery. It is a small price to pay for the peace of mind.

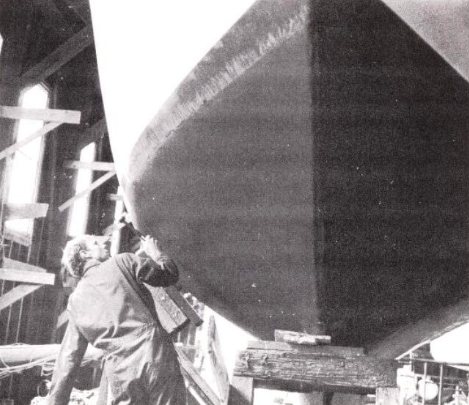

Most boat manufacturers attempt to build a good and work-manlike product. In some instances, a purchaser can hire a surveyor to follow the boat through its production and either supervise or observe significant aspects of construction such as hull layup, mating of the hull and deck, and the installation of bulkheads and machinery. Even if a manufacturer will not permit a surveyor on the premises because of the potential disruption of his work force, all is not lost. Your contract can provide that a core sample of the hull may be taken and analyzed prior to delivery to assure a quality of construction in accordance with designer specifications. Such specifications are often available from the manufacturer.

The safest course for any purchaser is to have his boat built under survey. Many marine surveyors have experience with supervising the production of sail and power boats. Lloyd’s Register of Shipping in England regularly supervises the construction of boats to their own standards of quality. In this country, most often the specifications originate with the designer or naval architect. A surveyor can physically observe the production of a boat to assure compliance with those standards.

Sea trials are an effective way of finding those little problems that can be so irritating during a new boat’s first year. Many dealers provide them, some manufacturers require that the dealers provide them, and any smart purchaser should insist on a sea trial in his contract.

Insist on a written copy of the manufacturer’s warranty. Ask the dealer for copies of any warranties which he offers, or warranties provided by the manufacturers of equipment installed on the boat. If, after seeing your boat, you have questions about any installations or questions about the quality of the boat’s production, by all means insist that an independent marine surveyor investigate.

The easiest way to remedy defects is to avoid them. The judicious use of a contract which clearly and unequivocally states the rights and obligations of each party should provide the protection that we all seek when buying a boat.

Finding a Marine Surveyor

Most likely, you will have to get a survey before you can complete the purchase of a used boat. Finance companies generally require a survey before they will lend you money. If not, they usually require insurance, and insurance companies require a survey before they will underwrite a boat more than two or three years old. Even if a survey is not required, it makes good sense to get a second opinion on any boat for which you are about to spend a large sum of money.

Costs for a survey will vary with the season and the area where the boat is located, running from about $ 6 per foot of boat in some areas during the off-season to as high as $ 15 per foot in the peak season in other areas. Surveyors also normally charge for car mileage beyond the local area and for expenses such as phone calls.

A survey for a typical 30-footer could run anywhere between $ 200 and $ 500. If the boat is in the water, a survey means that it will be hauled, with that cost normally paid for in advance by the prospective buyer. While this can all add up to a substantial sum, it is generally still a reasonable price to pay for safeguarding your investment.

Finding a Surveyor. Surveyors are not licensed or regulated in any way, and there is quite a diversity in competence and skill, When we had our own used boat surveyed, we were able to choose a local surveyor whom we knew was expert, with a good track record on work he had done for half a dozen friends and acquaintances. But on an earlier boat further away, we hired a distant surveyor based on the phone recommendation by the yard where the boat in question was stored.

Though the distant surveyor had been in business a long while and advertised extensively, he was patently incompetent at dealing with sailboats. Among other things, he missed a number of minor structural flaws, did not look at the rig, and failed to recognize that the boat had been painted. We later learned that the surveyor was primarily a powerboat man, but neither he nor the yard gave us any indication of that in advance.

The best way to choose a surveyor is on the experience of people you trust, and the mistake we made was to rely on a single recommendation from someone we did not know. Based on that experience, we developed a plan for finding a surveyor.

If you are dealing through a broker, first ask him for two or more recommendations. Most people are understandably a little skeptical of a single recommendation, since a broker is obviously in a position to throw a lot of business towards a surveyor who does well by the broker. The broker should easily be able to give you two names.

Next, call up another used-boat dealer in the area. Explain that you are buying a boat from another dealer and want a disinterested recommendation on the two best surveyors in the area. If you do not get any matching names or if you have some other reason to be sceptical, call another dealer or two.

We tried this process four times and were pleasantly surprised. All the brokers we talked with understood our position and were willing to spend a few minutes on the phone, even though they were going to make no money by helping us. For one dealer, a secretary even had a list that they apparently gave to all their used-boat customers.

After talking with six brokers in an area where we knew no one in the business, we had a list of seven surveyors whom we could easily rank from «best» to «less than best».

The next step is to engage the surveyor. It is best to do this yourself, rather than to let your broker do it. The surveyor should understand very clearly that you—not the dealer or the finance company – are the client and that the survey is undertaken for you and should be delivered to you.

When you talk to the surveyor, you should ask about more than price and schedules. A general question like «what will you look at in this boat?» will probably not give you much useful specific information, but the surveyor’s answer should indicate what kind of person you are dealing with – whether he is orderly or disorganized, knowledgeable or ignorant, thoughtful or merely glib, and so on. You can ask for references from previous customers or people in the boating industry if you are still concerned about the surveyor’s competence.

The Survey Itself. To understand exactly what goes on during a survey of a typical fiberglass boat, we accompanied Anthony Knowles of Newport Marine Survey on two trips, one to the used boat that we eventually bought. Incidentally, though most surveyors understandably do not like the client tagging after them, if you can observe the survey of your own boat it will be an enlightening experience, as the surveyor points out all the reasons why you should not buy the boat you have fallen in love with.

The procedures of surveyors vary somewhat, but the details are always directed at the same goal, assessing the value and condition of the boat (this type of survey is sometimes called a «value and condition survey»).

In the two surveys we witnessed, surveyor Knowles followed an extensive checklist, but gave very different emphasis to specific items on the list, reacting to the two boats in different ways based on what he found during the process.

The survey itself begins before the boat is even seen – in the surveyor’’s files where he keeps brochures, new-boat articles from old magazines, BUC price books, broker listings, previous surveys, as well as his own notes and other information he has gathered over the years.

The visit to the boat begins with a stop at the broker’s and boatyard offices, to pick up the list of equipment being sold, the combination to the boat lock, and the location of the mast or other equipment not stored on the boat.

At the boats, Knowles began with a quick once over, which was similar to what you would do going through boats at a boat show. The quick look provides the surveyor both a general impression, relevant mostly to the value of the boat, and a guide toward which parts of the boat need detailed attention and which can be disposed of more rapidly.

The next stage is normally an examination of the cosmetics and structural integrity of the hull. First the surveyor «eyes» the hull outside, looking for fairness, evidence of previous repairs, and existing problems like dents in the keel or dings and scratches in the gelcoat. Although we are experienced in looking at boats, our first comeuppance occurred when Knowles immediately identified an area of the topsides that had apparently been holed and repaired. We had totally missed this in our own look at the hull, even though it seemed obvious after the surveyor pointed it out. Locating the spot on the outside of the hull, of course, dictated a very thorough examination of the repair inside the hull at a later stage of the survey.

The next step is «sounding» the hull. Sounding involves tapping on the hull with a hard plastic hammer, listening to the sound each blow gives off. Interpreting the sound is a skill that requires experience; a good surveyor can supposedly tell not only the difference between a perfect and a badly delaminated section, but also many levels and nuances in between. Being able to interrupt and talk with Knowles during the two surveys, we were able to get a glimmer of the differences in sound, but this is clearly an area where an amateur would be wasting his time, even though «hull thumping» is a common activity among Buying a Used Boat: What to Look for, Tips for the Buyerused-boat buyers.

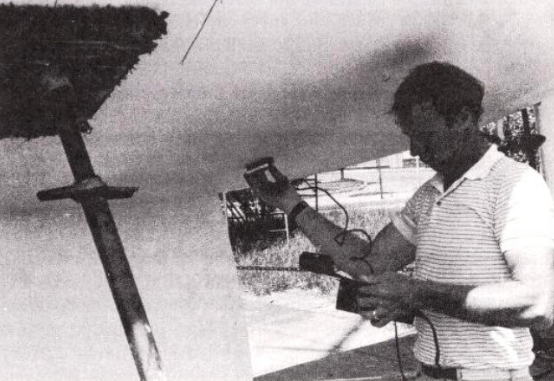

Still on the outside of the hull, the next step for Knowles was an electronic sounding of the hull, using a little machine called the Moisture Master, an English device only recently being imported into this country. Originally developed to measure the moisture content in cement construction work, the instrument found its way into marine surveying almost by accident, when English surveyors were searching for a method of identifying potential blistering in fiberglass.

The machine electrically measures the presence of moisture inside of any substance that its radio-frequency waves can penetrate, including fiberglass laminates and core material such as balsa or Airex foam. In essence, the instrument sends out a radio signal which responds differently to every substance it penetrates, depending on the electrical conductivity of the substance. Since water is much more electrically conductive than air or fiberglass, the radio signal will react differently when water is present. The moisture meter assesses the change in electrical capacitance and displays its results on a dial, showing low (or no) readings when the material is dry and increasingly high readings when moisture is present.

Since other substances (like steel or carbon fiber) react similarly to water and since even water acts differently at different times (like when it is freezing or in an acidic solution) there is considerable skill in interpreting the moisture meter. But after a year and a half of experience, Knowles finds the meter invaluable in examining cored hulls and very useful in solid glass hulls. He feels he is close to being able to predict whether a boat’s laminate is «wet» enough to be a likely candidate for blistering.

While an increasing number of surveyors are employing the moisture meter, its use is not yet universal by any means. Based on our quick look at it, we would be inclined to demand its use if we were buying a cored hull. If we had a choice between a surveyor who used the machine and one who did not, we would definitely opt for the one who was up to date on the technology.

The final steps outside the hull involve a check of the rudder and engine shaft and prop, looking for wear and play in the systems. This was followed by a close examination of the through-hulls and other fittings, and scrutiny of the topsides finish for any bad flaws.

On board the boat, the first check is the deck which was sounded for delamination or voids much as the hull was, except that the hammering is gentler, more a tapping than the whacking that goes on below the waterline. Since minor spots of delamination are common on balsa-cored decks, the surveyor is usually looking for more extensive soft spots that can cause concern for the structure.

Everything else on deck – fittings, hardware, hatches – is then checked over. We found it typical of the procedure that the surveyor checked everything very rapidly, then returned to potential problem areas. On the first boat, Knowles spent more time checking the deck hardware than everything else on deck (much of it was loose and leaking); while on the second boat, he spent most of his time looking over the teak decking and stanchion fastenings, potential problems areas to which he finally gave a clean bill.

Next came the inside of the boat. There, the process was somewhat slower, since the surveyor checked not only the structural integrity of the hull, deck, bulkheads, and floors; but also the cabinetry, plumbing and electrical systems, including everything from head to stove; and the equipment, from fire extinguishers to winch handles. Once finished with the hull and contents, the surveyor will inspect the rig if possible and any other readily available equipment.

Undoubtedly, different surveyors work differently. Knowles began at the forepeak and worked back to the lazarette, checking off items for each section of the boat on a structural/conditions checklist, a legal requirements/safety equipment list, and on a list of gear and equipment being sold with the boat.

Although the details and procedures vary with the boat, the most surprising thing to us was the greater proportion of time spent on basic structural aspects, and the relatively cursory attention to much of the equipment. For example, Knowles seemed to spend a great deal of time poking at a fiberglass covering of the ballast keel on one of the boats, but then dismissed four rusty, beat up snatch blocks with the comment «typical wear».

Generally speaking, it is the tendency of the buyer to look for virtues in a boat, but the tendency of the surveyor to look for problems. The buyer needs to keep this in mind when receiving the surveyor’s report.

The Report. Once the inspection is completed, the surveyor prepares a report, usually following a standardized, fill-in-the-blanks format. The report is an abbreviated version of the surveyor’s findings during his inspection. Here are some samples, with comments, from the survey we attended:

The underbody and topsides of the yacht were carefully inspected. The rudder appears to have been repaired and faired-in before painting. It is quite possible that further work may be necessary in the future, dependent upon the type of use this boat is subject to.

Uniform average readings were recorded on a moisture meter applied to the hull surface below the boot-top, indicating that no osmosis problem exists.

It is interesting that the rudder is singled out, because it is a problem area. In the actual survey, Knowles spent perhaps two minutes sounding and examining the rudder and nearly an hour on the rest of the bottom, which he scarcely mentions.

A thorough inspection of the hull interior was made, and apart from areas not visible or accessible because of cabinet work, tanks, machinery, etc., there was no sign of damage, repairs, or delamination, cracks, or notable corrosion except for the following:

The tabbing on the cabin sole-to-hull joint has let go which is quite common on a boat of this age, and a section of non-structural fiberglass in the bottom of the bilge has become loose.

The passage beginning «apart from areas not visible» is typical of survey reports and quite often bothersome to used boat buyers. It sounds like the surveyor is covering himself, which, of course, he is; and sometimes it sounds as if the surveyor has not done the job you have hired him to do.

There are a number of things the surveyor normally can not or will not do (like tearing apart joinery or going up the mast of a boat stored with the rig up), and these things left undone are always reported. These necessary omissions often take a prominent position in the report and seem to overwhelm the other parts, sometimes making it difficult for the buyer to feel confident in the conclusions of the survey.

The other areas that surveyors are generally reluctant to take on are the electronics, the engine and related machinery, and the sails – primarily because there is not a lot that a brief inspection can tell about them, especially when the boat is out of the water. As another surveyor said to us, «Show me a sail stored in a bag and I can tell you that it’s white and used, and not much else».

Near the end of the report, a section is usually given a subtitle something like «Recommendations». For one of the two boats surveyed, the list was long, including 15 items that the surveyor thought should be done before the boat was launched – such things as «replace the keel bolt load plates», «replace the galley sink drain hose and double hose clamps», and «replace the fuel tank filler hose».

For the other boat, the list was brief:

Deterioration due to age was observed concerning the following items – the alcohol stove and tank, the hot-water heater, teak-cockpit grating, port hole trim, slight delamination in the lazarette hatch, cabin sole-to-hull tabbing—but little major work must be done to make this yacht safe and seaworthy.

This yacht will only be considered a good marine and fire risk after the following repairs have been made: all the hose clamps throughout the boat must be replaced and doubled where they are below the waterline. The jacketed section of the exhaust from the manifold to the muffler must be replaced. I consider a short passage to a shipyard to repair this exhaust safe, if a good watch is kept for leaks.

Usually this recommendation section is designed to call your attention (and an insurance company’s attention) to the major problems with the condition of the boat. (When we went to insure the boat, the carrier required that all the defects listed in this section be corrected before the boat left the harbor.)

In the final section of the report, the surveyor will usually offer his opinion of the «fair market value» of the boat, based both on his examination of the boat and his estimate of the current market.

Although the survey will primarily be used to satisfy a lender and an insurance company, it should also be useful for the buyer. If any serious defects are discovered which were not apparent, you should consider modifying your offer for the boat, either asking that the defects be corrected by the seller or that the price be lowered an equivalent amount. You have to be reasonable about this if the boat and its equipment are used and not in like-new condition, and you should be careful not to use the survey as an excuse to renegotiate the contract. Nevertheless, the survey and sea trial is your last chance to alter or void the contract before the sale is finalized.

Finally, the survey should provide the first of your «work lists» for your new used boat.

Boat Financing

In many respects a boat loan is similar to a home mortgage, and like a home mortgage, there are a number of different types of boat loans:

- straight interest;

- variable interest;

- equity loans;

- balloon payment loans, and so on.

Still, there are some notable differences between boat loans and home mortgages. First of all, most boat loans are written for a shorter period of time, about half the usual duration for home mortgages, and most have higher interest rates than mortgages. However, the most notable difference is the nature of the equity involved. Unlike a home where the value of the house and land are likely to appreciate at a rate at least equal to the amount of interest paid to finance the purchase, the value of a boat will appreciate little, if at all, and certainly nowhere near to the amount of interest on a boat loan. Boats, unlike homes, are therefore poor investments and at best represent only the equity of the original cash purchase price. The interest on the money used to buy the boat has to be considered part of the annual cost of owning the boat.

Boat finance companies are most interested in loans of $ 25 000 or more, on up to 90 percent of the original purchase price. For the purchase of a smaller boat with a value under $ 30 000 or so, equity loans, second mortgages, or personal loans from lending institutions are sometimes more feasible.

Firms in the marine finance business know that the typical sailboat owner has historically been a good credit risk, and that the chances of his defaulting on his boat loan are slim. Nevertheless, in extending crediton the loan with the boat as collateral, the lender wants to know that, in the event of default, the lending firm can take possession of the boat and sell her for at least the outstanding balance on the loan.

In arranging for financing of a boat, do not put all your available cash into the down payment on the loan. In addition to the purchase price, there will be other costs that go with a new or used boat. These could include:

- sales tax;

- dockage;

- insurance,

and any other equipment or personal items you will want aboard but which will not be included in the sales price. These costs might total an additional five percent over and above the purchase price. With the annual or recurring expenses of owning a boat now running typically in excess of 10 percent of the value of the boat (not including the interest on the financing of the boat), a prospective owner would do well to assess his financial situation carefully before making a commitment on the purchase.

As a final word of warning, a boat is a plaything and thus her purchase and payments, unlike those of necessities such as a home or an automobile, should be made with disposable income. Certainly, ownership of a boat should not create a financial hardship. Remember, too, that the larger the boat, the longer it may take to convert the asset back into cash if you need it.

Marine Insurance

Normally, when contemplating a major purchase, a practical sailor will comb the stores, ads and discount houses for the best price. When buying an insurance policy, however, many of us simply contact a trusted agent and ante up the premium for the required coverage.

If you shop around before buying your insurance, you will find that prices vary greatly on equivalent coverage. If you delve into the policies themselves, you will find that policies with equal face values can have vastly different limitations. The majority of sailors will pay the annual premium and, fortunately, will never need to learn how good their coverage really is. For an unfortunate few, however, filing a claim will produce some disturbing surprises. Here are some of the limitations and exclusions to watch out for:

The Consequential Loss Exclusion. If you were to ask a hundred insurance agents to explain the «consequential loss exclusion» to you, regardless of whether they were employees of an insurance company or an independent agent, you would be fortunate indeed if even five of them knew what you are talking about. Of those who know the answer, few (if any) would voluntarily explain the exclusion to you before you buy a policy.

Most likely, you would get reactions like: «Don’t worry, you are in good hands» or, «Don’t worry, the company never denies this sort of claim».

Exactly what is the consequential loss exclusion, and how does it effect the security of your investment in your boat? In the most simple terms, the consequential loss exclusion (CLE) is an exclusion that says the company will not pay a loss or claim on your boat if it is the result of wear and tear.

We want to make it perfectly clear that we are talking about losses that result from wear and tear. We are not talking about paying for wear and tear as a claim. No policy will pay for a worn out part on your boat. Yet there are many situations where a worn out part on your boat will lead to an insurance claim. Take, for example, your through-hull fittings. They are subject to corrosion and electrolysis to the point that there are times when they simply fail and water enters the boat. With a policy that includes the CLE, you would have no coverage should your boat sink because of the failed through-hull. The scenario may go like this. On arrival at the marina, you find your boat has sunk in eight feet of water. You call your company who sends out an adjustor who in turn reports to the company that the sinking was because a hose clamp or a through-hull fitting rusted through. The result? No coverage.

Or, you and the family are out for a sail and suddenly, the rig goes over the side. Now you need a new mast. However, on investigation, the adjustor determines that the mast came down because a rusted and corroded swage fitting let go. Again, you have no coverage under the terms of the CLE. Of course, you might get lucky and have an adjustor that knows nothing about boats, who may go ahead and approve your claim. But do you trust to luck, or do you buy good coverage to begin with?

Now that you understand what effect the CLE can have on your boat, how do you find out if your policy includes the CLE? In most policies, under «hull exclusions», you will find an exclusion that says the following: «Excluding loss or damage resulting from or in consequence of wear and tear, corrosion, weathering». If you see this or similar wording, you have it. Do not, however, confuse this with the normal exclusion for wear and tear. Remember, no one pays for wear and tear. The key words are resulting from wear and tear.

Watercraft Liability Coverage. A holdover from years gone by is «watercraft liability» coverage. The normal yacht policy uses «protection and indemnity» (P&I), which costs more, but provides more coverage. For example, the normal P&I coverage will pay to remove your wrecked boat from a navigable waterway, whereas watercraft liability will not. P&I includes medical payments that will pay for claims on you and your family – not just for guests. Additionally, P&l attempts to provide legal coverage for matters of maritime law where watercraft liability simply provides coverage for civil liability. P&I then, is broader, addresses maritime law questions, and is designed for ocean-going yachts – especially important if you get into a fracas at the starting line of a race.

Actual Cash Value. Probably the second worse thing you can buy is a policy designed for small boats, such as outboards. These policies are inevitably written on an «actual cash value» (ACV) basis as opposed to the «replacement cost» normal to yacht insurance. ACV is something that most people understand, probably because they are used to it with their automobile insurance. Buy a new car and take it off the showroom floor and you suffer ten-percent depreciation. The same thing applies to a boat. Lose your mast and you may have to pay one-half the cost of replacing the mast. Add a deductible on top of this, and you really come up on the short end of the stick.

Occasionally, when asked if the policy is replacement cost, an agent will reply that it is «agreed value». Don’t get confused by this one. Agreed value simply means that if the boat is a total loss, they will pay the face amount of the policy. Replacement cost, on the other hand, will pay the face amount of the policy and will replace parts on a new for old basis. If you lose your mast, the policy will pay the full cost of replacing it; less your deductible, of course.

Other Exclusions. The variety of limitations and exclusions that some companies use in their policies is almost endless. One company might limit you to three miles offshore. Another might give you the Bahamas (which at their closest to the US are about 50 miles) and then turn around and limit you to 25 miles offshore. Some companies do not cover sails and rigs while racing; some will not cover racing at all. With such a variety of things like this, you must be careful to make certain that what you are buying will meet your needs.

For obvious reasons, there have to be exclusions in any policy, be it life insurance or boat insurance. Boats should be seaworthy. The boat owner who intentionally and willfully neglects his boat so that he can turn in an insurance claim, is a drag on insurance companies and on all of us, because he causes rates to go up.

Other items, such as defects in the design of a boat, which is a common exclusion, simply cannot be done away with or the insurance company would find itself in the boat-design business. This is best left to the naval architects who design the boats. This, for example, refers to a boat where a design defect caused it to heel over too much and might be the result of too little ballast being used or designed into the boat.

Help Your Agent Help You. Buying insurance immediately puts many people on the defensive. Constantly wary of saying too little or too much, one may never know what effect the information given has on premiums, and after the purchase, whether a claim against the policy will result in higher rates or cancellation.

The truth is that you do have a certain degree of control over the cost of your insurance and the recovery of losses which insurance is supposed to provide. In fact,a marine underwriter has to develop a feel for a prospective policyholder in order to determine how secure a risk he represents. You can help him with this task and help yourself in the process, by advising your agent of certain factors:

Experience. Go out of your way to inform your agent of passages, local sailing experience, length of experience, professional qualifications you may have, education (suchas US Power Squadron, US Coast Guard, or other courses you may have taken), types of boats with which you are familiar, and any other information you can think of to demonstrate your competence and familiarity with boats.

Seaworthiness of the Boat. Advise the agent of any unusual features of your boat which would contribute to its seaworthiness. If he is not familiar with your type of boat, make him familiar with it. Advise him of any equipment on board which makes the boat safer (fire control systems, radio telephones, depth sounders, Loran or other navigational equipment) or more secure (burglar alarms and locks). If you acquire such equipment, advise your agent; you will want the new equipment covered, and you may influence your rate favorably.

Claims History. Your claims history is reflected in the policy premium in various ways. Some companies award a discount percentage for each loss-free year. Then, if a loss occurs, you pay the full premium the following year, and start building up your discount with the next loss-free year. Thus, before filing a claim, you might check with your agent to see if you will forfeit a discount that amounts to more than your loss.

Some companies will let a single claim go, even a large one if you have a long loss-free history with the company, but will respond to a series of claims. You might be asked to buy a larger deductible, or your premium might be raised outright. A claim for a loss which involves poor seamanship on the part of the policyholder is more likely to elicit a response from the company other than types of claims.

Navigational Limits. Some companies offer lower premiums when a boat will be sailed within a small, specified geographical area, or if the boat is to be out of use for a substantial part of the year.

The Uninsurables. If you are shopping for insurance for an older boat, plan on a more difficult search – and a higher premium. As boatyard labor and materials costs rose dramatically in the 1970s, insurance companies began dropping older boats. To an insurance company, an «old» or «antique» boat is anything built before 1960. Frequently, insurance companies refuse to insure older boats, even those maintained in impeccable condition.

Since banks require insurance on boats used for loan collateral, it is often difficult to borrow money to purchase an older boat – particularly one built of wood. Insurance companies have argued that the high cost of the skilled craftsmanship required for wooden boat repairs causes severe problems for the insurance company.

In the last few years, there has been some easing in the insurance The Boat Market and Possible Force Majeure Situationsmarket for older boats. An increase in the demand for older boats, due to their relatively low cost compared to a new boat, as well as the growth in interest in old boats for their antique value, has created a fairly large insurance market that is not yet fully developed.

Several insurance companies have considered designing insurance programs directed at antique boats. If you go shopping for an older boat, go to a marine insurance agent or underwriter who may be able to offer such a policy. Even then, be prepared for the possibility that many insurance companies show little interest in insuring boats over 20 years old.

You must shop around if you wish to find the best combination of price, expertise, service and coverage. Though we cannot recommend specific companies, we offer this advice on how to find your own best buy:

- Be sure to investigate group rates or special programs, such as the insurance offered through the United Sailing Association, BOAT/US, or the Better Boating Association.

- Don’t be modest; insurance companies are likely to quote their lower rates to sailors with extensive, documentable training and experience, well-equipped and well-maintained boats, and good claims histories.

- When you have collected your quotations, select the two or three you like best and carefully read through the sample policy you have requested. Compare coverage as well as premiums, and make sure you understand the advantages of one policy over another.

- Choose an agent who is familiar with marine insurance, remembering that it is a specialized field, and that the agent you select will act as your advisor in the dealing with the company.

The New Boat Warranty

Your brand new boat has a badly blistered bottom, a delaminating deck, or some other serious defect. You have asked the dealer to repair it and he has either neglected the problem or is not skilled enough to put your flawed, expensive pride and joy right. You request help from the manufacturer and are met with either the classic stonewall or a blunt refusal to do anything to mitigate your woe. You are contemplating legal action, but where do you stand in terms of warranties and the law?

Source: wikipedia.org

In many respects, a boat is no different than anything else a consumer purchases. The law requires that it be manufactured in such a manner that it is merchantable; in other words, built in such a way that it will do the job that it was intended to do. This duty, imposed upon the manufacturer and to some extent on the dealer, flows from a number of different laws. Some of these are state laws and are, therefore, applicable only to persons who reside in a certain state or to contracts which are performed in that state. In addition to state statutes, there are federal laws that apply to yachts wherever they are located within the US.

State Law: The Uniform Commercial Code. At this writing, virtually all states have enacted the Uniform Commercial Code. This is a body of law that applies to the sale of goods, including boats. Under the Uniform Commercial Code, a buyer of a yacht is given numerous remedies against a seller for breach of express and implied warranties of fitness and merchantability.

Ordinarily a customer assumes a warranty is a written document given by a seller which warrants the goods against various problems. This is not necessarily true. There are different types of warranties; some are express, while others are implied by the law itself.

Implied warranties are created under the Uniform Commercial Code. When a boat is purchased from a dealer, it carries an implied warranty that the boat will be of at least average quality within the industry, unless it is specifically excluded or modified in writing. It is further warranted that the boat is suitable for a particular purpose when the dealer knows the purpose for which you intend to use the boat, and provided that you relied on the dealer’s judgment in making your choice.

Under the Uniform Commercial Code, when you find a problem with your boat, you must give notice to the seller of the breach of warranty, whether the warranty is express or implied. Once that is done, the seller must have the opportunity to attempt to remedy the defect in a reasonable manner. If he is unable to do so, you may have the defect remedied elsewhere and the seller will be responsible. In the most extreme cases, it may be possible to revoke your acceptance of the boat and demand all of your money back.

The Magnuson-Moss Act. The federal government has enacted a law, known as the Magnuson-Moss Act, that is important to the boat owner. Generally, that law is a remedial statute designed to protect consumers from deceptive warranty practices. It authorizes boat purchasers and other consumers to sue warrantors and suppliers for damages and other legal and equitable relief. The Magnuson-Moss Act primarily applies to boat manufacturers and it permits consumers to bring suit in a federal court if the consumer has an individual claim of at least $ 25 and provided the total amount in controversy exceeds or equals $ 50 000.

Under the Magnuson-Moss Act, the consumer is given four separate bases upon which to seek relief from a boat manufacturer for producing a defective product:

- The failure to comply with any obligation created under the law itself.

- The failure to comply with a written warranty given by the boat manufacturer.

- The failure to comply with a warranty that is implied under state law or under the federal law.

- The failure to comply with a service contract.

The statute of limitations under the Magnuson-Moss Act is four years, which is the same as the statute of limitations under the state Uniform Commercial Code. In most cases, this means a boat owner will have to take action within four years of delivery of the boat. However, the statute of limitations is subject to interpretation in terms of duration and the prudent course is to secure good legal counsel.

Under the Magnuson-Moss Act, the manufacturer of a product may give either a full express warranty or a limited express warranty. If the manufacturer gives a limited express warranty, he cannot totally disclaim liability for an implied warranty, but he may reasonably limit the duration of the written warranty. Any such limitations must be clearly disclosed on the written warranty itself. Under the Magnuson-Moss Act, a boat purchaser who brings a claim for breach of warranty, and who is successful in his claim, may also recover his costs, his expenses, and his attorney’s fees.

Federal Boat Safety Act. Another federal law that may apply is the Federal Boat Safety Act. When a boat buyer discovers a manufacturing defect which he believes is safety related, he may call the Boating Safety Division, Standards Branch, of the United States Coast Guard. Under the Federal Boating Safety Act, if the Coast Guard determines that the defect complained of is safety related, the Coast Guard has the power to compel the manufacturer to repair or replace the defect at the manufacturer’s cost.

Read also: Technical Recommendations for Inspecting Your Boat

If, after investigation by the Coast Guard, it is discovered that a manufacturer has produced a number of vessels which contain similar defects, then the manufacturer will be required, by mail, to notify the first purchaser, any subsequent purchasers known by the manufacturer, and any and all dealers and distributors of the defective vessels or equipment. This duty to notify will be imposed for defects found and reported within five years of the date of manufacture. Should the manufacturer fail to comply with the Coast Guard’s order, then it may be held liable to the US government for civil penalties which can total $ 100 000.

So, if persuasion fails and you need to resort to legal action, be aware that there are federal as well as state laws on the books to help protect your investment in your boat.

Whether you are buying a new or used boat, take your time and spell out your entire agreement regarding the purchase of your boat in writing. Remember, memory does not always serve correctly and a written record can save a lot of aggravation and possibly a lot of money.

Documentation Versus State Registration

Each year, more and more pleasure boats are being documented with the federal government rather than registered with a state government. Still, there seems to be a common misconception that the process involves considerable difficulty and frustration. One recent report called it, «a long and wearisome struggle with bureaucratic red tape», and recommended that the process be left to one of the numerous firms that provide the service for fees that average upward of $ 200.

This may be true in some complicated cases, but anyone considering completing the documentation himself should not be put off easily. Documenting can be done fairly easily by anyone with either a new boat, a previously documented boat, or one which has a bill of sale from all previous owners. All it really takes is the scrupulous observance of a few simple instructions, and some time.

The reason why more and more boat owners are opting for federal documentation rather than state registration is more than the small savings in state registration fees. There are three major advantages: The first is security. Unlike most state registration procedures, it is necessary to prove clear title to a boat in order to get it documented. This means that the buyer has an additional measure of protection against purchasing a stolen boat or one with a lien against it. Because of that protection and the fact that a lender can file a «preferred status» mortgageon the vessel with federal authorities, many lending institutions prefer documentation; some require it.

Second, because a documented boat is legally defined as a «vessel of the United States» and does not have to file registration of any kind with a state government, there may be certain tax advantages as well as avoidance of troublesome jurisdictional decisions when boats are moved often.

Third, as a US-registered vessel, there is some additional protection and convenience when cruising foreign waters. Moreover, the theft of a documented vessel is a federal crime regardless of where it occurs. Perhaps more important, however, is that a combination of all three reasons usually adds up to lower insurance rates and higher resale value.

On the other hand, there are a few disadvantages to documentation. Only boats over approximately 25 feet are eligible under a rather complicated qualifying formula; clear title may be difficult to prove on older boats; there are restrictions on the sale to non-citizens of the United States; and the boat is more subject to expropriation in time of war.

If the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and your boat can qualify, there is no reason not to pursue documentation yourself. If you do, there are several precise steps to follow. These steps are neither complicated nor particularly time-consuming. They must, however, be followed precisely.

For any boat not previously documented, you must start by getting a bill of sale from every previous owner right back to the time when it was brand new. There are no exceptions permitted to this rule.

For any boat, you will need to have the builder give you a completed «Master Carpenter’s Certificate» (CG Form 1261). This certifies that the boat meets certain federal requirements and gives some information needed for documentation.

With either of these (sets) of documents in hand, you should contact your local Coast Guard marine inspection office to get the necessary forms. Marine inspection offices are located at every major US port, but if you have difficulty getting an address, ask your local Coast Guard station.

Coast Guard marine inspection offices are most helpful and tolerant of the average boat owner’s ignorance of the documentation procedure. Not only will they provide the appropriate forms, but most likely they will also assist you in filling them out in the proper fashion.

The actual number and type of forms you will need to file will depend upon whether the boat is being documented in an individual’s name, or in the name of a corporation. In either case, you will need to complete forms to designate the official home port of the vessel, to apply for official numbers, and to apply for admeasurement (determination of official size).

If, for tax or other reasons, you wish to document the boat in the name of a corporation, you will also need a copy of the corporation’s «Certificate of Incorporation», a Coast Guard form certifying that you have the authority to sign for the corporation, another form that lists the officers and directors and certifies that all are US citizens, and still another that certifies that the boat is, indeed, owned by the corporation.

The actual requirements vary from situation to situation, but the total number of papers submitted for documentation is usually less than ten. A Coast Guard marine documentation officer will select the specific forms you need. Selection of the actual port of documentation is up to you. It can be any one of the ports around the country in which the Coast Guard maintains a marine inspection office. You do not need a mailing or business address in the documentation city. It is quite appropriate to request assistance from a local marine inspection office to help you fill out and check the appropriate forms, even though you intend to mail them to a inspection office in another city for the actual documentation. Just keep in mind that you must specify which city the documentation will take place in on the forms, and you must have the actual processing done there.

The completion of the process can take anywhere from one to six months after submission of the paperwork, depending upon that particular inspection office’s paperwork load. Since legally, most boats cannot be put into the water without registration of some type, the wait can be quite annoying.

When the documentation is done, you will first receive a notification of the official number of the vessel and its determined net tonnage. Then, somewhat later, you will receive an official looking piece of paper called, «The Ship’s Document». Henceforth, The Ship’s Document will be to the boat, what your birth certificate is to you.

The document must be kept on the boat at all times and be available for inspection when requested. Any liens or mortgages or attachments must be recorded on it. It must also be renewed by the Coast Guard every time the ownership or the name of the boat changes.

The official number and net tonnage given the boat must be permanently marked on the main beam in three-inch or larger Arabic numerals. In wooden boats this is usually done by carving, in steel boats by welding, and in fiberglass boats by fiberglassing a carved wooden plate to the foremost bulkhead.

Boat Ownership and the Tax Reform Act of 1986

Interest on boat loans is still deductible because a boat qualifies as a second home under the new tax code. But for some sailors, especially those with big, expensive boats, there is a trap in the new tax code. It is hidden in the alternative minimum tax.

When computing your «regular» income tax under the new tax code, a taxpayer can deduct «qualified residence interest». The taxpayer can have two qualified residences – a home, or «principle residence», and a second «dwelling unit» which can be, among other things, a boat. For a boat to be a dwelling unit, it must have «basic living accommodations such as sleeping space, toilet, and cooking facilities». Satisfy these criteria, and the boat becomes a second home.

For a typical, upper-middle class sailor with an income of $ 100 000 or less and a $ 50 000 boat, all he probably has to worry about is the above mentioned regular tax. However, if he or she makes enough money, and has a certain pattern and magnitude of deductions, that taxpayer will fall under the provisions of the alternative minimum tax.

The alternative minimum tax is designed to keep those with a substantial income from paying too little in taxes. If you have tried to reduce your taxable income with hefty deductions and credits, you may become an alternative minimum taxpayer. When computing the alternative minimum tax, you get a $ 40 000 exemption (for joint returns); however, you also lose most of your deductions and credits. The tax rate on your reworked taxable income is 21 percent.

One deduction you do not lose when calculating the 1987 alternative minimum tax is qualified housing interest on a qualified dwelling. In section 56(e) of the new tax code, a qualified dwelling is defined as any «house, apartment, condominium or mobile home not used on a transient basis». No mention of boats anywhere. That means that, even though you can deduct boat loan interest when figuring regular tax, you cannot when figuring the alternative minimum tax.

New Rules for Yacht Management. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 has resulted in major changes in the bare boat charter industry. It eliminated the investment tax credit, and changed the depreciation schedule on charter boats from 5 years to 10 years. If you are an alternative minimum taxpayer, you have to recalculate depreciation on an 18-year schedule. That cuts deep into the owner’s potential write-offs.

Boat mortgage interest is still a potential write-off. Unfortunately, tax reform classifies a bare boat charter operation as a «rental activity under the passive loss rule».

That means that the boat owner cannot deduct expenses that total more than charter income. For example, if you take in $ 8 000 in charter income, you can offset that income with up to $ 8 000 in deductions. But if you have more than $ 8 000 in deductions, which is likely if you have a mortgage and depreciation schedule on the boat, you cannot apply those deductions to income from your primary occupation.

This passive loss rule, as it applies to charter boats, is a significant change, because it is mechanical and automatic. You cannot get around it. Before the Tax Reform Act of 1986, you also were prohibited from deducting losses in excess of income, if you got into bare boat chartering to create a «paper loss» on your tax return. This comes under Section 183, called the «Hobby Loss Rules».

The difference between then and now is that, in the past, people ignored the rules and deducted paper losses anyway. To beat the IRS, they had only to convince the IRS that they expected to make a profit. «Active participation» in the management of the boat helped to demonstrate a profit incentive, and actually making a profit in two out of five years was sufficient proof of a profit incentive.

Now, paper losses on bare boat charter boats are clearly disallowed. However, if you satisfy Sections 183 and 280A, you are allowed to carry forward your paper loss. This means that you accumulate the deductions in excess of the charter income. When you finally sell the boat, you can use those accumulated deductions against income from any other source, including your primary occupation. Taken all at once, these deductions may not have the punch that they would if split up over several years, but it is clearly better than nothing.

Remember, however, that you must satisfy Sections 183 and 280A. Section 280A is effectively unchanged by the new tax code. As before, you must restrict your use of the boat to 14 days, or 10 percent of the total chartered days, whichever is greater. As mentioned above, Section 183 requires you to demonstrate a profit incentive and take active participation in the investment. Before the Tax Reform Act of 1986, making a profit in two out of five years was accepted as proof of a profit incentive. Now it is three out of five years.

To ease the shock of these tax law changes, Section 469 of the new tax code phases in the passive loss restrictions over five years. In 1987, you will be allowed to keep 65 percent of your passive loss; in 1988, 40 percent; down to zero in 1991, But alas, even this is not as good as it sounds. The alternative minimum tax does not phase in passive loss restrictions – if you fall under its jurisdiction, you lose all the deductions right from the start.

The added restrictions of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 will push more investor-owners into crewed charter boats. A crewed charter boat is a «business activity», not a «rental activity». That gets you out of the passive loss restrictions, and allows you to take all of the losses in the year you incur them. However, you still have to show a profit incentive.

Incidental Chartering. For the interest of a boat loan to be deductible for regular tax, the boat has to be a qualified residence. The section of the new tax code describing a qualified residence is Section 280A. It is here that we find the description of a dwelling unit (sleeping space, galley, toilet).

By referring to Section 280A for the description of qualified residence, the authors of the new tax code have placed restrictions on the boat owner who charters his boat incidentally. The same rules that define whether a charter boat is a rental activity also define whether a personal boat is a residence. If it is not a rental activity, it is a residence. You do not want to get your boat classified as a rental activity.

Section 280A says if your personal use of the boat exceeds 14 days, or 10 percent of the total days chartered (whichever is greater), then it is a residence, and you can deduct interest on a boat mortgage (but not under the alternative minimum tax).

On the other hand, suppose you charter the boat for a week, then use it yourself on five other weekends, for 10 days of personal use. Under Section 280A your boat is not a residence, but a rental activity. This means that, if you try to deduct the interest, you are going to create a paper loss on your rental activity. Because it is a rental activity instead of a residence, you now have to satisfy the passive loss rules of Section 189 and the profit incentive requirements of Section 183. That is going to be very difficult for the owner of the incidental charter boat.

The sailor who charters his boat incidentally should make sure he uses the boat himself at least 14 days to keep it classified as a residence. It is true that the IRS is not going to know how many days you use your boat, but if you know the rules before you get backed into a corner in the auditor’s office, there is that much less of a chance that you will get stuck there.

The good news is that the income from incidental chartering remains tax free under the new tax code. Just keep the boat classified as a residence. This makes owner-managed chartering far more attractive than yacht management by a distant company, because with incidental chartering, you can keep the interest deduction (assuming you are not an alternative minimum taxpayer).