Keel Types Comparison is essential for understanding the various options available to sailors. Different keel designs, such as full keels, fin keels, and winged keels, offer unique advantages and disadvantages. Full keels provide improved stability and tracking, making them ideal for long-distance cruising.

In contrast, fin keels allow for better maneuverability and speed, which is beneficial for racing. Winged keels offer a compromise, providing lift and stability with reduced draft. By examining these differences, sailors can make informed decisions that best suit their sailing needs.

The Full Keel Versus the Fin Keel

«I don’t want a boat with a fin; I want one that will steer. You know, one with a full keel».

It is remarkable how often this comment or the equivalent punctuates conversations and letters from buyers in the market for a boat. Many seem to reject a hull form without a full-length keel as directionally unstable, all but impossible to steer off the wind. Similarly, any boat with a rudder separated from the after end of the keel is a «racing boat».

It seems odd in this day and age that the myth about the relationship between keel length and steering ease continues to flourish. Keel length is only one of a lot of factors that affect the balance and directional stability of a boat. Beam, angle of heel, sail plan, rudder size, propeller size and location, sail trim, as well as wind strength and sea condition are also major factors. The memory still lingers of a first «big boat» we sailed, at age 12 or so, with a tiller two inches in diameter and enough weather helm to be so painful that for years afterward we regarded all big boats as beasts and stuck to sailing small stuff. That hard steering boat had a long traditional keel, this being years before the likes of the Cal 40 in the 1960s when the separation of keel and rudder became fashionable.

Secondly, «full keel» is a relative term. By the time designers began in earnest to separate the rudder from the keel, «full keels» had become remarkably short, so short that the rudder attached to the after end began to lose efficiency. Remember the Columbia 50? Her keel got so short that her designer, Bill Tripp, moved the rudder to the after end of the waterline and made it a spade rudder. It is now typical for the profile of a more or less «modern» underwater hull configuration to feature the rudder on a skeg aft but with most of the original full keel intact. The modern version responds more quickly to her helm than the original and tracks at least as well.

Several factors led to the demise of the fondly regarded traditional long keel. One is that designers sought to produce better performance in lighter winds by reducing wetted surface. Since wetted surface is the primary source of resistance in lighter winds, keels became shorter and shorter, with the result that their attached rudders were moved forward to the point of inefficiency. At the same time, designers found that shorter and deeper keels produced better windward performance.

Another factor has been the trend toward lighter displacement. For a variety of reasons, including cost and the high strength-to-weight characteristics of modern boat building materials, the weight of modern boats has tended to decrease compared to older designs. This reduction has decreased the immersed hull volume, hence the size of keels.

A third factor is the elimination of the need for the fore and aft structural stiffness that full length keels once provided. With smaller sail plans (to go with lighter displacement) and inherently stiffer materials, modern hull shapes can be adequately stiff without the full-length support of the deep vertical beam represented by full-length keel forms.

It is true that extreme examples of cutaway underwater profiles can result in steering problems on any point of sail. That is indeed one price racing sailors pay for minimal wetted surface and close windward angles, all in the name of ultimate performance. The keel form, however, does not carry all the blame. The problem is compounded by the wide, shallow hull forms with sharp ends encouraged by rating rules; by tall, narrow rigs; and by the sacrifice of seamanship for speed – three factors that have nothing to do with keel configuration.

A word about spade rudders is appropriate here, in view of tendency to lump the faults of the spade with those of the fin. Almost as soon as rudders were separated from the keel, designers hit upon the semi-balanced spade rudder (no skeg) for maneuverability. The problem with the spade rudder is that steering became too «busy» under sail and more so under auxiliary power. The lingering irony is that fin keels, and not the spade rudders behind them, earned the criticism for lack of directional stability. The answer was to mount the rudder behind a skeg, settling the helm appreciably and coincidentally improving the hydrodynamic shape of the hull aft.

Arguing about the relative merits of full keel versus fin keel is thus much like arguing politics or religion. Those dogmatic enough to argue are probably too dogmatic to consider changing their beliefs. Suffice it to say, there are good Instant Naval Architecture of Sailboatsfull-keel boats and good fin-keel boats, just as there are bad boats with both configurations. Admiring or dismissing a boat merely on what is likely to be an ambiguous perception of the effects of her keel configuration seems hardly worthwhile.

Winged Keels

The newest notion to take flight with advertising hype are wings (or wing lets) on keels. Wings on keels are intended to perform two different functions: to increase the hydrodynamic efficiency of the keel as lateral resistance upwind, and to lower the weight of the ballast. End plates to improve efficiency and a thickened keel bottom have both been played with for years, and designer Henry Scheel long ago patented a variation, his Scheel keel. However, wings on keels rarely attracted attention until 1983 when designer Ben Lexcen (in conjunction with Dutch hydrodynamicists) put them on Australia II and won the America’s Cup. Wings instantly became the hottest new item in boat design.

But let’s put them in perspective. First of all, the keel of a 12-Meter has always been basically inefficient. The draft, hence keel efficiency, of a Twelve is effectively limited by its class measurement rule, a situation compounded by a Twelve’s heavy displacement, also dictated by the rule. These two factors make it difficult to achieve effective lateral area, one reason why 12-Meters also typically incorporate a trim tab at the after end of their keels. Moreover, stability is crucial; the relatively shallow draft of a conventional 12-Meter prevents getting weight as low as possible. The wings may indeed have improved the efficiency of the Australian keel (which, even apart from the wings, was highly innovative) and improved the stability, but to what extent they did either is still a matter for debate.

Keel wings are not legal under the IOR. For PHRF, they are a modification that must be reported to the handicap committee and for which there should be a rating penalty, although no one seems to know how much since it is so difficult to assess their influence on keel effectiveness and stability. Remember too that wings are essentially only a possible improvement to windward; off the wind they represent drag.

Perhaps the most serious question of all is their practicality when there is a chance of bouncing off a rock or snagging a line or net. Wings are far more fragile than the solid mass of a streamlined keel. A grounding could do serious – and expensive – damage. Add to this the possible difficulty in hauling a boat with wings on the keel by conventional methods. (Twelves are lifted and lowered straight up and down with hardware attached inside on the top of the keel).

Then there is cost. A keel with wings as added ballast is difficult to mold and mechanical attachment of the heavy wings is not a simple matter, either. Designer David Pedrick recently had a complete steel frame welded up to support the wings on a keel for a custom 50-footer.

Just affixing wings for the sake of wings does not seem to be an answer. Their addition to the 12-Meter Courageous made no discernible difference in performance. Winged keel Six-Meters have not distinguished themselves against conventional keels in head-to-head racing. To use wings to increase keel effectiveness requires a calculated and tested design which takes advantage of the particular characteristics of wings that contribute to performance. To date we can see little evidence of such effort despite the advertising claims.

We have nothing against design progress, and winged keels may yet prove to be progress. Nevertheless, don’t confuse advertising hype with progress, and weigh possible progress against uncited drawbacks.

Shoal Draft

Everyone knows that shoal draft makes a boat slower, but few people can tell you exactly how much slower. Even naval architects have difficulty measuring the effect of shoal draft precisely. An architect who works for a highly respected design firm says his customers commonly ask what will happen to performance if they opt for reduced draft on their new boats. His office will estimate the effect of shoal draft, but he admits that they really cannot predict for sure how the boat will sail.

The question of shoal draft versus deep draft is an important one, though, especially to readers whose sailing is restricted by shallow water. Shoal draft literally opens up new horizons to their sailing. To try to pin down the real effects of shoal draft, we analyzed the PHRF ratings of some of the most popular boats which are offered in both shoal draft and deep draft versions. We also took a look at two boats that have been measured under the MHS rule. Comparing the ratings indicates that, for the most part, shoal draft does not deserve the bad reputation it has. The difference in performance is surprisingly small.

The Compromise of Shoal Draft

Shoal draft compromises upwind performance more than any other point of sail. As you reach farther off the wind, the effect is less and less, and on a broad reach or dead downwind, shoal draft is usually a bit faster. The effect depends largely on how shoal draft is achieved. Each method of reducing draft has its own particular drawbacks.

If you simply cut off the bottom of the keel, the reduced ballast causes the boat to lose stability and heel more easily. This causes the boat to make more leeway when sliding to windward. In addition, the more you heel the more weather helm you will have to fight, a problem which is accentuated on be amy boats.

If you reduce the depth of the keel without reducing ballast (by making the keel longer or thicker), it will still be slower than a deep keel. First, the keel will be less efficient hydrodynamically. Second, a thicker or longer keel will create more drag. Third, there will still be more weather helm, even if the boat does not heel excessively. This is because the rig acts as a lever arm, in the fore and aft plane, and is resisted better by a deeper keel acting as a lever arm in the opposite direction than by a shorter keel. The way to prevent this is to shorten the rig, which also hurts upwind performance.

Many shoal draft designs house a centerboard inside a shallow keel, which helps solve the problems of weather helm and excessive leeway. However, it increases the problems of drag due to the thick keel that houses the centerboard, the exposed slot in the bottom of the keel, and the pendant used to raise and lower the board.

A swing keel is a weighted centerboard without a centerboard trunk; it swings back flush with the bottom of the hull. Properly engineered, this system can offer superior performance, averaged over all points of sail, to a deep fixed keel, if the swing keel extends to a much greater depth than the fixed keel.

The Catalina 22’s swing keel version, for example, draws 5 feet with the keel down; the fixed keel version only draws 3 feet 6 inches. PHRF ratings show the swing keel version to be slightly faster, even though the keel is a rough iron casting. The Chrysler 22, however, also offered with a swing keel, is faster in the fixed keel version, because the difference in draft between fixed keel and extended swing keel is less; the fixed keel draws 3 feet 9 inches while the swing keel draws only 4 feet 6 inches.

What the Rules Say About the Difference

The PHRF rule is a handicapping system based on observed performance. Instead of measuring a boat in order to mathematically estimate how it will perform, actual on-the-water performance is used. The longer a boat has been racing, and the greater the number of observations made of design’s performance, the more accurate the rating will be.

The MHS rule is a complex handicapping system based on a tremendous number of measurements. Although there are still bugs being worked out of the MHS, it is generally regarded as a “fair” rule for most boats. Predictably, MHS and PHRF ratings are relatively close for popular production boats. With the MHS, however, you can get a computer printout of a boat’s potential performance on all points of sail and in any wind velocity. The PHRF does not distinguish between wind velocities and assumes performance on a course with equal amounts of beating, reaching and running.

MHS. Only two production boats measured for MHS are offered in comparable deep keel and shoal draft versions: the C&C 36 and the C&C 40. There are many comparable designs rated under PHRF. By looking at the C&C 36 and 40 we can arrive at some general conclusions about the performance of all shoal draft designs.

According to the MHS rule, the deep draft versions of the C&C 40 and the C&C 36 are faster around a race course than their centerboard counterparts. The C&C 40 is, on the average, 6,1 seconds per mile slower with a centerboard, while the C&C 36 is only 3,3 seconds slower. The reason that the C&C 40 is «more» slow is that the difference between its two configurations is proportionally greater. The C&C 40 draws 7,4 feet in the deep draft version, and 4,8 feet to 8,5 feet in the centerboard version; the deep draft C&C 36 draws 6 feet, while the centerboard model draws 4,4 feet to 7,8 feet. Therefore, the shoal draft C&C 40 is more of a compromise.

The difference in seconds per mile is deceptively small for the two boats under MHS. That is because the rating is for a «linear random» course, which assumes that a boat sails a straight line while the wind shifts around it through 360 degrees so that equal amounts of time are spent on all points of sail. When you consider only upwind performance, the seconds per mile difference is 2 to 3 times greater.

For example, on a one-mile upwind leg in a 14-knot breeze, a C&C 36 is 11,4 seconds faster in the deep keel version, while on a linear random course it is only 1,8 seconds per mile faster. This means that a deep keel C&C 36 will have gained 86 more feet directly to weather after a one-mile beat in 14 knots of wind. In 20 knots of wind, the gain is only 70 feet to windward, but in 8 knots the deep draft version will be 138 feet upwind of the shoal draft boat after one mile.

For those who think this difference in upwind performance is insignificant, you must remember that the two versions of the C&C 36 represent the average amount of compromise that occurs with shoal draft. The C&C 40’s compromise is more than average. In an 8-knot breeze, a C&C 40 with shoal draft will be 236 feet to leeward of a deep draft C&C 40 after one mile of sailing upwind. This figure drops to 192 feet in a 14-knot breeze, but jumps to a whopping 261 feet in 20 knots of wind.

You must also consider that the compromise of shoal draft quickly disappears as you bear off. By the time you are broad reaching, the effect is insignificant. When running, shoal draft is almost always slightly faster. The advantage when running is not something to get excited about – with the C&C 40 and C&C 36, it is usually less than 0,4 knots.

PHRF. For popular production boats, a PHRF rating is a good measure of potential performance. The popular boats, offered in both deep keel and shoal draft versions, which have been extensively raced under PHRF are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1. Deep Draft Versus Shoal Draft | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Keel vs. Swing Keel | Deep Draft Rating | Shoal Draft Rating |

| Catalina 22 – deep draft version is 1,1 seconds per mile faster | 270,4 | 271,5 |

| Chrysler 22 – deep draft version is 11,5 seconds per mile faster | 256,5 | 268,0 |

| Balboa 26 – deep draft version is 3,2 seconds per mile faster | 214,9 | 218,1 |

| Deep Keel vs. Shoal Keel | ||

| Hunter 25 – deep draft version is 2,9 seconds per mile faster | 223,6 | 226,5 |

| Islander 28 – deep draft version is 5,3 seconds per mile faster | 197,3 | 202,0 |

| Hunter 30 – deep draft version is 3,1 seconds per mile faster | 182,1 | 185,2 |

| Islander 36 – deep draft version is 10,3 seconds per mile faster | 142,0 | 153,2 |

| Deep Keel vs. Centerboard | ||

| Tanzer 22 – deep draft version is 2,6 seconds per mile faster | 237,0 | 239,6 |

| Ericson 25 – deep draft version is 9 seconds per mile faster | 232,8 | 233,7 |

| O’Day 30 – deep draft version is 3 seconds per mile faster | 176,4 | 176,7 |

| C&C 34 – deep draft version is 6,6 seconds per mile faster | 143,1 | 149,7 |

| C&C 36 – deep draft version is 4,9 seconds per mile faster | 128,0 | 132,9 |

PHRF is an acronym for Performance Handicap Racing Fleet. It also refers to a handicapping rule based on the observation of a boat’s performance, rather than on measurements (like IOR or MHS). PHRF ratings are usually based on a equal amount of reaching, running and beating, as most races start and finish at the same point. For this reason, PHRF ratings give a good indication of the differences in overall performance of deep draft versus shoal draft boats of the same design. Because shoal draft hinders performance upwind but not running, the difference between shoal draft and deep draft versions of the same boat, shown in the table below, would be greater than the rating indicates if only upwind performance is considered.

For the most part, MHS ratings for production boats are similar to their PHRF ratings. Because the PHRF ratings are based on a course that has a greater percentage of windward work, the difference between the shoal draft and the deep draft versions is slightly higher. For example, under MHS the C&C 36 is 3,3 seconds faster with a Choosing the Right Boat – Your Ultimate Guide to Selecting the Ideal Vesseldeep keel; under PHRF it is 4,9 seconds faster.

Using the MHS as a basis for determining performance on different points of sail, and taking into account that PHRF will usually give more credit to shoal draft, here is how to determine how much slower a boat will be upwind. Take the difference between the two versions under PHRF and multiply by 2 to 2,5. For example, the Islander 36 is 10,3 seconds per mile slower with shoal draft under PHRF. Upwind, however, it is probably 20 to 25 second per mile slower.

Shoal draft will hurt your boat more upwind than on any other points of sail. When considering performance on all points of sail, the difference is almost insignificant. So what if you are 5 seconds slower per mile on a beam reach? Upwind, however, you will be 10 to 15 seconds slower than you are on a beam reach. Even so, 15 seconds or 100 feet per mile is not going to ruin your day. The difference in performance from one boat to another, or from a well-sailed boat to a poorly sailed boat, is likely to be far more significant.

Heavy Displacement Versus Light Displacement

Although the owners of many boats are primarily concerned with light weight for trailering or high performance for racing, there are sailors who want boats of relatively heavy displacement. Some, but not all, of these sailors want heavy boats for the right reasons.

Unfortunately, heavy displacement is often equated with poor or sluggish performance. To an extent, the relationship is justified. During the last twenty years, while the performance of sailboats has improved as boats have become lighter, a number of production boats have been notable as heavy and slow. Most notable, of course, is the Westsail 32, but the sisterhood includes a host of designs adopted for chartering and many others built in the Orient.

The common denominator of these heavy boats is their so-called traditional or classic character. They have full-bodied, double-ended hull forms with full or long keels. They are rigged as cutters or, worse, ketches with low aspect sail plans that boast bowsprits to increase sail area, yet seldom include overlapping head sails with their greater efficiency. Many further restrict performance by ragging solid, three-blade propellers in large, unfaired apertures.

The disturbing factor about many of these boats, both large and small, is that they seem to flaunt their stodgy performance. Asa result, many sailors have grown up believing that heaviness and slowness in some mystical way guarantee seaworthiness. This is a sad misconception.

Misconceptions about Heavy Boats. There is no reason a heavy boat has to be slow. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in the designs of Ted Hood. Hood has designed a number of superbly performing cruising boats and racers that have remained competitive, despite the trend toward lighter and lighter boats.

The key is, of course, that boats that perform well have well- designed sail plans with adequate sail area, set on spars that are efficient, over a hull that is stable and sea kindly. The underwater surfaces are fair, wind age has been kept to a minimum, and the boats are not overbuilt or loaded down below their designed waterline. Note that there is nothing in these modest standards that in any way impinges on tradition. In this day and age, there is no reason a sail must have the shape of a bag; a mast, the heft of a log; or a rudder, the bluntness of a plank.

In further contradiction to apparent popular belief, heavy displacement does not ensure a more comfortable motion than a light boat in a seaway. It can, however, help. Some heavy-displacement boats roll mercilessly in certain conditions, a discomfort compounded by tedium if the boat is slow or poorly balanced. Nevertheless, heavy-displacement boats are not generally subject to the snappy motion that afflicts light boats, nor do the better ones require the attention to the helm or to sail trim.

Even better news is that weight does not automatically mean poor performance in light air, an argument often lost amid the ecstatic outbursts from sailors on light boats as they plane by heavy boats in a strong breeze. Once having gained momentum, a heavy boat with adequate sail area may leave its lighter and short-canvassed cousins in its wake in light air.

Conceptions and misconceptions aside, the chief advantage of heavy displacement, especially in smaller boats, is that for the same overall length, the heavy boat can be more roomy and carry a larger payload than a light boat without affecting performance.

To illustrate this point, take the installation of an inboard auxiliary engine in a small boat, for example. Install a 160-lb diesel engine plus a fuel tank in a 26-foot boat with a modest displacement of 3 600 pounds, and her displacement increases by almost eight percent – more than the weight of an additional crew member. The same engine, still adequate for propulsion in a 8 000-pound boat, is a comparatively insignificant increase – less than three percent.

For this greater displacement there is a price. Displacement means a greater amount of materials plus the labor to assemble them. Coincidentally, heavy boats have more sail area, which, in turn, means Masts and Rigging Systems for Sailing Shipsheavier rigging and fittings. They may also need larger engines, more tank age, and more complicated systems, all costly. Ironically, heavier displacement may not mean more ballast, but, then, ballast is relatively cheap compared to the rest of the structure of a boat.

The Trend Toward Lighter Boats. Now that modern materials and building techniques are producing lighter boats, and cost is often the major factor in boat selection, it is no wonder that there are fewer and fewer heavy boats on the market. Builders of heavy boats have suffered; Westsail has disappeared, CSY folded, and so has Allied. Now the most common source for heavier boats is the Far East where low labor costs help keep heavy boats competitively priced.

Whereas livability (space, carrying capacity, sea kindly motion, etc.) is the major advantage of a boat with heavy displacement, the top priority for the light boat is performance (speed, liveliness, and so forth). In general, these two priorities tend to conflict; heavy means roomy and light means fast. Neither relationship is guaranteed, but there is certainly no reason to pay the price in performance of a heavy boat and be cramped, nor to have a light boat and be slow.

A boat is considered heavy when her displacement-to-waterline length ratio is about 300 or more, and ultralight when it is under 100. Few modern yachts exceed 400 (a notable exception is the Westsail 32 with a ratio of 425); the trend has been away from exceedingly high ratios. At the other end of the scale, lower and lower ratios have been sought by several builders. The Santa Cruz 27, the boat that has attracted the most attention to the «fast is fun» light-displacement concept, has a ratio of 95; the Olson 30 has a ratio of 77; and the skinny Fast 40, with a displacement of just 4 160 pounds on a 36-foot waterline, has a ratio of 40.

Comfort and Construction. While the popular notion is that heavy displacement means more comfort at sea and better overall construction, it is hardly axiomatic that light displacement results in the opposite. Comfort ts a relative term. The corkiness of a light boat may make for a bumpy ride, especially to windward, and awkward steering off the wind, but it also means that with the wind from abeam aft, the ride will be fast.

Aficionados of lightness point out that on a passage of 2 000 miles, the heavier boat may take 20 days and a light boat half that time, particularly when she can surf or plane. While the crew of the heavy boat spend the 10 added days in relative comfort, the crew of the light boat enjoy complete dockside comfort after their exciting 10 days of sailing.

Construction quality is less subjective but no less controversial. One characteristic of the heavy boat is that she must be built strongly to carry the rig to move her weight. With greater rig size comes greater loads. Conversely, because a smaller sail plan and smaller rig is needed to move the light boat, construction can be lighter. In addition, the heavy boat tends to sail through seas while the lighter boat sails over them, a motion harder perhaps on the crew, but easier on the hull and rig.

In this day of technological developments, strong does not have to mean heavy. The aircraft industry has produced a whole line of exceptionally strong lightweight materials that can be applied to boat construction. F-Board, aluminum honeycomb faced with an epoxy-fiberglass laminate, is stronger, at a fraction of the weight, than the plywood normally used for bulkheads, cabin sole, and structural cabinetry.

Similarly, carbon fibers, vinylester resins, Kevlar fabrics, and balsa and foam coring materials are now regularly used to build lighter hull and deck structures with superb strength. Even present-day plywoods are lighter and more attractive than the plywoods used a few years ago.

For lightness, however, there may be a price. It is common knowledge that heavy boats generally cost more than boats of average displacement because there is more material and labor in their hulls, and because they have larger, more costly rigs, hardware, and engines. Only in the largest and heaviest boats built of materials such as ferrocement and steel does the relation-ship between cost and weight begin to level off.

At the other end of the weight scale, the labor and materials to produce lightness are also expensive (although the cost is coming down). If in the interest of saving weight, the builder uses state-of-the-art materials and techniques, that pushes the cost upward dramatically.

Where the builder of the modern light boat can save on production cost is in the vestigial interior accommodations often provided in these boats. Joiner work is the single most expensive component in the boat building process. Keeping joiner work, hence accommodations and amenities, to a minimum saves weight and cost.

Untrimmed plywood cabinetry, extensive use of vinyl and other fabrics for overheads and ceilings, curtains rather than doors, scuttles rather than drawers and lockers are all cost-cutting techniques which balance the expense of lighter, stiffer hull laminates, a stronger keel attachment, and beefier rudder assemblies. Only when the buyer insists on first-class accommodations and the performance of ultralight weight does the cost rise precipitously.

The Issue of Stability. Contrary to popular belief, there is no reason why a light boat should have appreciably less stability than a heavy boat. Stability (stiffness) is only partly a function of weight. Stability is also a function of ballast, hull form, and the height of the center of gravity (affected by a number of factors including rig weight, hull construction, and the location of tank age, stores, engine, and crew).

Because crew weight makes up a larger proportion of the sailing displacement on a light boat than it does on a heavy boat, the location of that weight is more important to trim and stability. That is why, when the crew sits along the weather rail in a breeze upwind, the conditions when stability is most a factor, there is a greater effect on performance in a light boat than in a heavier boat.

Then there are the questions of ultimate and inverted stability: How easily can a lighter boat be rolled over by seas and, once capsized, how readily will she roll back upright? The low free-board, wide shallow hull, and low cabin house of the typical light boat do encourage rolling over. So too does her relative lack of weight and mass; the light boat may be better able to withstand the impact of a wave on hull, deck, and cabin structure, but be less able to withstand the tendency of the wave to roll or to pitch-pole the boat. This is treated in more detail later in this chapter.

Source: wikipedia.org

Although the weight of the ballast under a light boat may be less than or equal to that under a heavy boat of the same waterline length, the proportion of ballast to displacement is usually greater. The most popular modern heavy-displacement boat, the Westsail 32, has a ballast-to-displacement ratio of 36 percent, whereas the Olson 30 has a ratio of 50 percent as does the Santa Cruz 50.

Combined with a lighter rig and hull structure, the higher ratio means that the effectiveness of the ballast may be greater for the light boat than for the heavy. However, the light boat rapidly loses performance as the angle of heel increases. Light boats are meant to be sailed as nearly upright as possible. Whereas a heavy displacement boat may sail well with her rail close to the water, the light boat at even moderate heel angles becomes increasingly unmanageable, leeway increases, and speed drops.

Add to this drawback the fact that the light boat seldom has a powerful enough rig to move her through sloppy seas, and it is easy to understand why most of the lightest boats perform at their best in a relatively narrow range of conditions upwind. Moreover, in heavier winds and seas their motion can be snappy and exhausting.

Downwind Is the Way to Go. Downwind is a different story. Virtually any boat but the heaviest can surf down the face of a following sea given sufficient wave height and distance between crests. The lighter the boat, the quicker and farther she will surf, and she will do so on smaller and shorter waves. Boats with displacement-to-length ratios below about 100 can also plane when their speed is no longer restricted by the wave formation of their hull. This ability to surf and plane in even moderate conditions is a big part of the appeal of light boats, and one of the major reasons for their fast downwind passages.

The concept of the very light boat offends many purists and traditionalists, while the boat’s speed and rating characteristics often drive rating-rule makers to distraction. However, the «fast is fun» phenomenon is clearly here to stay. Light boats offer something many modern sailors crave. They are not for the blue water cruising sailor nor are they for the coastal cruising family. Yet for the lowest price per foot, and the lowest price per knot, they cannot be ignored.

Displacement-to-Length Ratio

The displacement of a boat is equal to the weight of the water displaced by the boat as it floats upright in the water. Thus the displacement of a boat is the weight of the boat. Traditionally, displacement is simply an application of Archimedes’ Principle that a body immersed in water displaces a volume of water equal in weight to that of the immersed body.

Traditionally, displacement is used as the measure of the weight of a vessel because the volume of a hull below its designed waterline (DWL) can be calculated more easily than actually weighing the boat. The volume in cubic feet is multiplied by the weight of water per cubic foot (usually sea water at 64 pounds) to give the displacement.

Another formula for the area of a boat hull at her waterline gives a figure for the additional displacement needed to «sink» the boat an inch below her DWL. This permits the difference in displacement to be calculated if the boat does not float on her designed waterline.

The important factor in determining whether a boat is «heavy» or «light» is the ratio of displacement to waterline length. The formula for the displacement-to-length ratio is the displacement in long tons (2 240 pounds) divided by one hundredth of the waterline length cubed:

For example, according to the builder, the Ericson 30 has displacement of 9 000 pounds (4,02 long tons) and a waterline length of 25 feet, 4-1/2 inches:

Smaller boats tend to have higher displacement-to-length ratios than larger boats. The traditional average ratio for boats with a 20-foot DWL is about 300; for a 25-foot DWL, 275; and for a 30-foot DWL, 250. If the displacement-to-length ratio of a boat is within 20 percent or so of the average on either the heavy or light side, her displacement is considered moderate. Higher than that, the displacement is heavy (the Westsail 32 is 425); lower, it is light (the Cal 9.2 is 190). Light planing boats have a ratio closer to 100 or even below (the Olson 30 is 77).

In recent years the average displacement-to-length ratio for sailboats has been getting lower and lower as boats get lighter and lighter. Three major factors are at work causing this trend. Waterlines have been getting longer in proportion to overall length. This combined with the use of modern building materials has permitted hulls and rigs to become lighter. Finally, the marketplace has been highly sensitive to price and price is a function of weight.

For the modern fiberglass production boat with a DWL of about 25 feet or less, the average ratio is now closer to 250. The Flicka with a displacement-length ratio of 334 is heavy even by traditional standards. For comparison, note the ratios for a number of other popular small production boats in Table 2.

| Table 2. Displacement-to-Length Ratios of Common Boats | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy | Light | Moderate | Ultralight |

| Westsail 32 – 425 | O’Day 22 – 173 | Nor’Sea 27 – 292 | Santa Cruz 27 – 96 |

| Flicka – 334 | Tanzer 22 – 168 | Int’l. Folkboat – 290 | Moore 24 – 89 |

| Stone Horse – 325 | MacGregor 22 – 147 | Columbia 76 – 223 | Ohlson 30 – 77 |

| Cape Dory 25 – 307 | J/24 – 139 | Ericson 25 – 214 | Hobie 33 – 60 |

In calculating a displacement-to-length ratio there are some important factors to keep in mind. First, the figures supplied by builders for the displacement of their products are seldom precise. Some are little better than estimates. Few spell out under what conditions the boat will displace the stated amount, whether loaded on a trailer as she leaves the factory, or fully loaded ready for cruising. The manufacturer’s displacement figure usually does not take into consideration the added weight of food, sails, clothing, or spare parts; nor does it include crew members. Obviously, the addition of this weight affects the displacement of a small boat the most. The addition of 600 pounds of crew and stores to the light MacGregor 22, for example, increases that boat’s displacement more than 20 percent; the addition of the same modest amount increases the much heavier Flicka’s displacement by less than 10 percent.

Sail Area-to-Displacement Ratio

One factor that can be used to predict the performance of almost any boat is the relationship between sail area and displacement. If displacement represents what must be moved, then sail area represents the power to move it.

The ratio of sail area to displacement is best indicative of relative performance in moderate winds – how quickly the speed of the boat can be expected to increase as the wind strength increases. The same ratio gives a fair indication of how quickly the boat may accelerate after tacking or after being slowed by a large wave.

The formula for determining the sail area-to-displacement ratio is the nominal (or rated) sail area in square feet divided by the displacement in cubic feet to the two-thirds power:

To determine the displacement in cubic feet, divide the displacement in pounds by 64, the weight of a cubic foot of sea water.

Since the head sail overlap or the setting of multiple head sails (i. e.,a stay sail and jib topsail) are not taken into account, the ratio is not a direct indicator. However, as a general parameter for predicting performance from available specifications, the sail area-to-displacement ratio should be added to such equally calculable parameters as the displacement-to-length, ballast-to-displacement, and speed-to-waterline length ratios.

A sail area-to-displacement ratio of about 15 or less is likely to indicate a boat that is underpowered for her weight. The average for a cruising boat is between 15 and 17. Some ultralight boats have comparatively high ratings. These figures may be misleading unless one realizes that the usual figure for displacement does not take into consideration the crew weight and stores. These will increase the actual sailing displacement of a light boat by a much greater proportion than the same additional weight on a heavier boat.

Using published figures (which are subject to some suspicion), we calculated the sail area-to-displacement ratios for a number of familiar boats. These figures are shown in Table 3.

| Table 3. Sail Area-to-Displacement Ratios of Common Boats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DWL | DISPL. | SAIL AREA | SAIL AREA/DISPL. | |

| Southern Cross 31 | 25′ | 13 600 | 447 | 12,5 |

| Nicholson 32 | 24′ 2” | 14 750 | 497 | 13,2 |

| Westsail 32 | 27′ 6″ | 19 500 | 631 | 13,9 |

| CSY 32 | 25″ | 15 200 | 538 | 14,0 |

| Endeavour 32 | 25′ 6″ | 11 700 | 470 | 14,6 |

| Seawind II | 25’6″ | 14 900 | 555 | 14,7 |

| Catalina 30 | 25′ | 10 200 | 444 | 15,1 |

| Hunter 30 | 25’9″ | 9 700 | 473 | 16,6 |

| Sabre 30 | 24′ | 8 400 | 432 | 16,7 |

| Ericson 30 | 25′ 4-1/2″ | 9 000 | 470 | 17,4 |

| Cal 31 | 25′ 8″ | 9 170 | 490 | 17,5 |

| J/30 | 25′ | 7 000 | 453 | 19,8 |

| Santa Cruz 27 | 24′ | 3 000 | 396 | 30,4 |

Will She Capsize in Heavy Weather?

As marvelously technical and theoretical as the sport of sailing is, basic Choosing the Right Boat: A Guide Based on Your Experience and Budgetresearch into sailboat performance and safety has remained remarkably informal over the years. Recently, however, that situation has been changing. Since the mid-1970s, a great deal of research has been going into the design of sailing yachts. Much of that research has been done in conjunction with formulating various rating rules and designing boats to race within those rules. In turn, much, if not most, of what is done for rulemakers and designers eventually trickles down into the production boat market and to the sailors who buy production boats, including those to be used exclusively for cruising.

Read also: Technical Recommendations for Choosing Engines for a Boats

One of the major pieces of research into making boats safer was the product of the 1979 Fastnet Race when, during a storm, a disconcerting number of boats rolled over, capsized, sank or were abandoned. What happened to the Fastnet fleet begged for a study of what forces cause boats to be rolled over by heavy seas, what characteristics of boats contribute to their being rolled, and what can cause a boat to remain inverted long enough to pose the threat of sinking the boat and drowning her crew.

Two groups joined forces for the capsizing study: members of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME) and the US Yacht Racing Union (USYRU) formed the Joint Committee on Safety from Capsizing. Members of that four-man committee were:

- Olin Stephens;

- Karl Kirkman;

- Dan Strohmeier;

- and Richard McCurdy.

What the Joint Committee Learned. The study by the Joint Committee found that, while smaller boats are more vulnerable to capsize than larger boats, any boat can be capsized if rolled over by a wave big enough. Thus the Committee focused on two issues: what design parameters resist capsize, and what parameters reduce inverted stability.

The three factors the study determined as most significant are beam, Buying and Selling Making – a Sound Investment In a New or Used Boatballast location, and mast weight. Narrow boats, research found, are more resistant to capsize and less prone to remain inverted if rolled over than beamy boats. Similarly, boats whose ballast is deeper and hence have a lower center of gravity are more resistant. Third, since a heavier mast imparts greater inertial resistance to rolling than a lighter mast, mast weight contributes significantly to capsize resistance. Moreover, if sealed to prevent water entering in the event of being rolled under, the mast can reduce negative stability. The importance of the mast in resisting capsize suggests that the rig must be strong enough to withstand dismasting; a capsize that dismasts a boat leaves that boat even more vulnerable to being rolled over with subsequent seas.

Note that the committee was not dealing with the quickness a boat heels initially to a gust of wind, or the «stiffness» a boat may have at normal sailing angles. A multihull or a beamy monohull especially with her crew seated on her windward rail may be extraordinarily stable (stiff) at relatively small angles of heel. However, at larger angles, both can quickly lose stability and be vulnerable to capsize, even to «turning turtle».

Source: wikipedia.org

As a boat is rolled over by wind, waves or a combination of both forces, she increasingly loses positive stability as the roll angle approaches 90 degrees. By the time the masthead reaches the water, the angle will be close to 100 degrees. When a boat is rolled beyond the angle at which she has positive stability, she will continue to roll over. The wider the boat and/or the higher her center of gravity, the less the angle is at which she loses positive stability.

The greater the angle at which a boat retains positive stability, the more resistant that boat is to capsize. Moreover, the greater that angle, the less is the angle of negative stability and the shorter the duration she is likely to remain inverted in the event she is rolled over. The committee’s findings suggest that a minimum angle of about 120 degrees of positive stability is desirable for offshore boats.

While no boat can be made immune to rolling over, some boats are better at resisting – and surviving – capsize than others. Although in general bigger boats are more resistant than smaller boats, even boats of the same size may be markedly different in their capsize capabilities.

To account for these differences, the committee developed a formula that determines «capsize length». The greater her capsize length the more resistant the boat will be to capsize. A typical modern yacht of moderate displacement and beam has a capsize length approximately equal to her waterline length. Heavier and narrower boats have a longer capsize length whereas wider, shallower, and lighter boats may have a capsize length only half of their waterline length.

A look at actual reports of capsizes suggests that a capsize length of 30 feet or more offers acceptable resistance to capsize, especially if the rig is heavy to provide roll inertia that further resists rolling over.

How can you tell which boats are better?

Calculated Answers. The most precise method available is to get an International Measurement System (IMS) rating certificate for the boat (or a sistership). That certificate, from actual measurement of the hull and rig of the boat, calculates the range of stability for that boat. If IMS calculations indicate an angle of less than 120 degrees as the limit of positive stability for his boat, a prospective owner may want to get a more definitive assessment of the boat’s capsize resistance.

A second way to determine the resistance of a boat to capsize is to use the «screening formula». While this formula was originally formulated to help race committees «screen out» boats whose low resistance to capsize makes them unsuitable for offshore races, it can also tell whether any boat is acceptably or unacceptably resistant to being rolled over. Note, however, that the formula only addresses the issue of a boat’s vulnerability to capsize; it says nothing about whether a boat may be unsuitable in other ways – through flimsy construction, a violent motion that fatigues the crew, inadequate rigging, and so on.

Although the screening formula was originally designed to use the data from rating certificates, any prospective owner with the specifications for a boat can reasonably determine her capsize resistance with his own calculations. Parts of the formula are quite simple, but they have to be used with caution and with an understanding of exactly what the terms mean.

The first and most usable stage of the screening formula reads: In order to be eligible to participate in a race of Category one, a yacht must have a capsize screen value less than or equal to 2,00, as given by the following formula:

The terms are taken from the International Offshore Rule (IOR) and refer to complex measurements made of an IOR racing yacht to give it a handicap rating. If your boat has an IOR certificate, you can simply take the figures off the certificate and plug them in. (If a sister-ship has an IOR certificate, you can order a copy from USYRU for $ 3, which should give you figures that are close enough for you to make a personal judgment about capsize resistance of your own boat.)

Lacking an IOR certificate, a person can approximate their terms – provided sufficient care is taken – and come up with usable figures to plug into the formula, for a boat under consideration for offshore sailing. («Offshore» is defined here as «long distance and well offshore, where yachts must be completely self-sufficient for extended periods of time, capable of with-standing heavy storm and prepared to meet serious emergencies without the expectation of outside assistance».)

«B Max» is fairly simple – you can simply use maximum beam in feet. Measure it yourself, or if you use the manufacturer’s figures, remember that the published figures are rarely very precise.

«Displ» is more complicated. Under the IOR rule, it is a «calculated displacement» which averages somewhere in the neighborhood of 10 percent lighter than the actual sailing weight of the boat. Arriving at a displacement number for a boat that has never been measured or weighed is difficult. The displacement that is quoted by a manufacturer may be the «design displacement» (what the designer wanted the boat to weigh), or the «as-built displacement» (ready to roll out of the builder’s yard), or the «sailing displacement» (ready for racing or cruising), or maybe even wishful thinking. The fact is, most boat manufacturers cannot usually tell you what their boats actually displace in sailing trim.

We have come up with a rough but usable way of estimating a displacement for the screening formula by comparing published statements of weight with actual or calculated weights. The figure needs to be used with caution, however, especially if the screen value comes out near 2,00, which is the point at which a yacht would be deemed unacceptably resistant to capsize.

Without a known weight for your boat, you can only begin with the displacement figure published by the manufacturer as it appears in owner’s manuals, sales literature, and sailing magazines. You will have to assume that this is probably a «partially loaded» weight and you will have to add the weight of some equipment to arrive at a displacement figure comparable to the one in the formula.

In your calculations, the following equipment can be considered part of the sailing weight:

- anchors;

- chain;

- anchor rode;

- batteries;

- navigational equipment;

- cooking equipment;

- mattresses and cushions;

- safety equipment (life jackets, man-over-board poles, etc.) sheets;

- guys;

- blocks;

- winch handles;

- and all sails.

Not considered part of the sailing weight are personal gear, dinghies and life rafts, food, and other miscellaneous gear.

You should not count tankage (water and fuel) in your calculation. Obviously, how much all this gear weighs depends in part on the size of the boat: a 26-footer’s ground tackle and sails will not be nearly as heavy as a 40-footer’s (though it may be a much higher percentage of the total weight). If you want an extremely crude figure, try adding four percent for boats weighing up to 5 000 pounds; three percent for boats weighing 5 000 to 10 000 pounds; and two percent for boats weighing over 10 000 pounds, to account for the difference between published displacement and the sailing displacement.

So our new, rougher calculation is:

(The 1/3 means «cube root». You will need a good calculator to figure that out.)

For a specific example, we will use the $ 27,9. The manufacturer lists the displacement at 4 250 pounds. We weighed the boat in sailing trim (for a MORC certificate) and found the actual figure to be 4 487 pounds. The beam was measured at nine feet exactly. Our calculation then is:

Or, a screening value of 2,18. That is, the S 27,9 would not pass the screen and would not be allowed to race in an offshore event that used the formula; the boat would be considered too liable to capsize in the event of severe conditions.

For the 7,9’s next larger sister, the 10,3, we calculated sailing weights of three boats from the MHS certificates, at an average of 11 164 (compared to the manufacturer’s list of 10 500). Plugging that weight in, we arrive at 2,03 – closer but still unsuitable.

For racing, the screening formula allows a boat which fails the first calculation to go on to a second level – using a more precisely determined displacement figure. If a boat also fails that level – as did all three S2s – then a third, more precise formula could be used.

Unfortunately, to use the third level, you need to have figures that are not normally available without an MHS or IOR measurement and virtually impossible to approximate. These figures include the «measured sailing length», a location of the boat’s center of gravity, and a «roll moment of inertia» figure. You use a formula to determine a «capsize length», and the screen requires «a capsize length greater than 30 feet, and a range of stability greater than 160 degrees minus capsize length», to be accepted for Category I races. (For readers interested in this third level, it would be best to get a copy of the full capsize report from USYRU (Box 209; Newport, RI 02840). You will also need the 1984 «interim» report which contains the algorithms for calculating some of the data you will need.

In our analysis, we found that an S2 10,3 did not, in fact, pass the third stage of the screening formula, with a capsize length of 29,73 feet, and so would not be accepted in an offshore race. However, the figure was close enough that we would personally be comfortable taking the boat offshore – especially considering the quality of its construction and rig. We did not have sufficient information on the 7,9 to enter the third level of the screening formula, but it is far enough up the scale at 2,18 that it seems obvious that this is not an «offshore» boat.

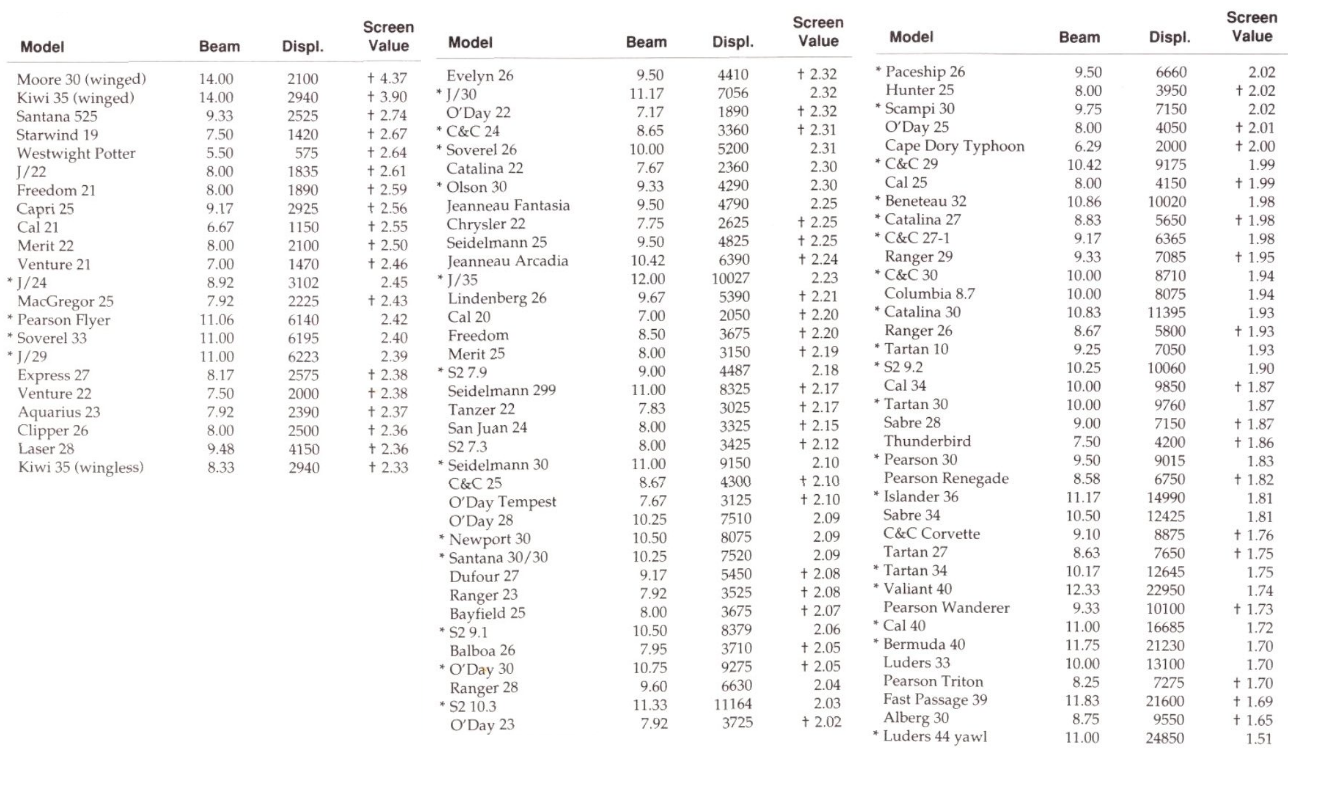

This table lists a selection of boats, arranged in decreasing order (right hand column) from «most vulnerable to capsize» to «least vulnerable». The screening cutoff point for offshore races is 2,00. Boats above 2,00 would have to satisfy more rigorous Measurement formulas to qualify. These boats would probably be regarded as unsuitable for offshore racing, although the larger the boat, the better chance she will have of passing the more complicated screens.

An asterisk (*) next to the model name indicates that those boats have MHS measurements on file which could be used for a more in-depth examination of capsize vulnerability.

A dagger (†) in the Displacement column means that beam and displacement have been estimated, usually from manufacturer’s figures, but occasionally from IOR or MORC certificates.

The point is that it would be wise for anyone looking for an answer to the question: «Will she be safe offshore?» to be very cautious about boats that come out of the first formula with answers near 2,00. Considering the rough nature of the information that will be used for most boats, we would think the careful owner would go beyond level one with a boat which screened between 1,90 and 2,10. And the smaller the boat, the more important it is to check further, since capsize vulnerability is directly related to size. We would want any boat under 30-feet LOA to be well down the scale.

To go to the third level would require an MHS certificate. A small number of boat builders have paid for MHS «standard hull» measurement of their line of boats so the information is available at a modest cost to owners. We chose S2 for our examples because they are one such company; J-Boats and C&C are two of the others.

If you are considering a boat with an MHS «standard hull» measurement, you can buy a copy of the measurement certificate ($ 8 from USYRU). Otherwise, you will have to pay the full cost (about $ 450) for MHS measurement. Still, the cost may be a reasonable investment if you have questions about the safety of a particular boat offshore.