Choosing the right boat is a pivotal decision for any prospective boat owner. It’s essential to consider how you’ll use the boat, whether for leisurely sailing, fishing, or long-distance cruising. Understanding various construction methods and keel types can greatly influence performance and stability. Additionally, the design of the deck and cockpit plays a crucial role in comfort and usability.

- Choosing the Right Boat

- How Will She Be Used?

- The Cost of Owning a Boat

- The Right Boat: Construction

- The Right Boat: Keels

- The Right Boat: Decks

- The Right Boat: Cockpits

- Center Cockpit: Yea or Nay?

- The Right Boat: Belowdecks

- The Right Boat: Main Cabins and Galleys

- The Right Boat: Engines

- The Right Boat: Rigs and Rigging

Don’t forget to evaluate below decks spaces, like main cabins and galleys, to ensure they meet your needs. Ultimately, making an informed choice will enhance your boating experience for years to come.

Choosing the Right Boat

Given the thousands of new and used boats available on the market, the prospective buyer faces a bewildering task. How, amid the conflicting claims, can the average buyer come up with the right boat? A cynic might say that it does not really matter what boat you choose. They are all too expensive, they all break, and you are likely to use her so little anyway that it hardly matters which boat you buy, so just buy one and go sailing.

It is possible, however, to determine needs and abilities, weigh the options carefully, and with a little luck and a lot of perseverance come up with a boat that exactly fills the bill.

The two big questions to be answered when buying a boat are: How will she be used, and what will she cost? Implicit in those two questions is an almost endless array of other questions, some of which are easily answered, and some of which will always remain unanswered.

How Will She Be Used?

When choosing a boat, you must be realistic about what you will do with her. Will you day sail with the family, with occasional day racing? Is weekend cruising high on the list of things you want to do? Are you really going to take that trip to Hawaii or Bermuda, or is that a dream for the distant future?

Obviously, a heavy ocean cruiser is out of place on a lake. Less obviously, she may be out of place in many coastal light-weather areas, too. Choose a boat suitable for most of the sailing you do. You will never find a boat that is perfect for all your sailing. If 90 percent of your sailing is day sailing on summer weekends in protected waters, buy a boat that is at her best in those conditions.

This may require considerable down scaling of your dreams. To some extent, almost all of us consider the boat to be a means of escape from our usual routine. Above and beyond the recreational aspects of the boat, she functions as a psychological cushion between the reality of the 40-hour work week and the dream of escape. Too often, perhaps, the dream dominates reality when the time comes to spend hard-earned dollars. This situation is hardly helped by much of the sailing industry’s advertising, which touts every boat over 25 feet as a blue water cruiser, and every boat under 25 feet as an easily handled trailer-sailer with plenty of room for a family of five and two dogs. The industry also gets great mileage by playing on our dreams, so that we frequently end up with a boat more suitable for the type of sailing we would like to do than the sailing we really do.

The Cost of Owning a Boat

The price tag on any boat is only a percentage of the cost of owning a boat. In addition to the cost of equipping the boat, there is the cost of maintenance, insurance, dockage, and storage. For a boat that is used infrequently or a boat larger than what is really needed, the cost per sailing hour can be staggering. If you are only going to use a boat for a few weekends a year, chances are that it makes far more sense to rent or charter than to own a boat.

A major cost of owning a boat that is not always apparent when you buy is what it is going to cost when you sell the boat. Boats are poor investments, even though you may be able to sell your boat for more than you paid for her. While some boats might retain their value relative to inflation, few boats actually appreciate more rapidly than the rate of inflation.

As hard as it may seem, you must consider the boat’s resale value before making the purchase. A boat is not a lifetime investment, no matter how perfect she seems now. Taste changes, your use of a boat changes, your expectations change. If you are a new sailor, the growth in your experience may lead to the desire for another type of boat very quickly.

There is no way to guarantee a high resale value for any boat, but there are simple rules to follow to protect yourself: Buy a boat that is popular in your sailing area. Buy a boat that has a local dealer with a reputation of giving good service. And buy a boat with a proven track record.

A boat that is popular where you sail is likely to be easier to sell when the time comes, and is likely to sell for a higher percentage of her original cost. The Whumpty Dump 25 may be a better boat than the Wham Bam 26, but if you have the only Whumpty Dump in an area where the Wham Bam is popular, you are likely to take a bath when you sell her.

One reason that a particular brand or model may be more popular than another comparable boat is the quality of the local dealer. Some dealers give excellent after-sale service, organize local racing or cruising, and help to find dockage or storage for the boats they sell. In this way, they develop customer loyalty that is translated into future sales. Another dealer may seem helpful before the sale, but give you the cold shoulder after he has your money in hand. The only way to be sure about a dealer is to ask people who have bought boats from him. It pays to talk to more than one of the dealer’s customers, however. The dealer is not always at fault in a transaction that goes sour. If he has a consistently poor reputation, however, there is likely to be more than a grain of truth to the complaints.

A boat that does not have a local dealer is unlikely to have a substantial local following no matter how good a boat she is. Having the only Blue water 45 within 200 miles of your sailing area may garner you admiration at the local yacht club, but she is likely to return less of her original cost when the time comes to sell her.

Unless you are willing to put up with some headaches, it is better not to buy a brand new model, even if she is built by the most reputable builder in the world. Every brand new boat has some teething problems, and if she is a brand new model as well, the problems are likely to be compounded. Every boat evolves during her production life, and this evolution is almost always for the better. Changes in engines, hardware, components of the interior layout, even rig changes are not uncommon. Independent of the actual condition of the boat or her age, where she falls in the production series is quite important. It may be nice to have the newest model, but that boat-show glow can quickly wear off after a long series of warranty claims and factory retrofixes.

Sail the Boat. It goes without saying that you should try to sail the boat before you buy it. If a boat is popular in your area, chances are good that you can find an owner who will take you for a sail. If you show a serious interest, most owners will take the time to talk to you about their boat, even if they are not selling their own boat.

Sailing the boat is even more important if she is a relatively uncommon boat in your area. A short sail may quickly reveal why a boat is not particularly popular. A single sail is not guaranteed to show the boat’s good and bad points, however.

Finding the right boat is more than a matter of luck. It is more than a matter of visiting boat shows or dealer showrooms, although both of these are important. It is a matter of introspection and self-scrutiny, the patience to do your homework and to wait for the right boat rather than jump at the first one that strikes your fancy.

Buy a boat for the type of sailing you want to do now, not the type that you might do in five or ten years. Your taste may change with the growth in your abilities. Unless you are a remarkably single-minded individual with a goal absolutely incapable of being altered by the vagaries of life, buy for today’s needs, not tomorrow’s.

Dreaming is an important part of sailing, one that cannot and should not be ignored. A dream tempered by a healthy dose of realism has a far greater chance of becoming realized. And the fulfilling of dreams, rather than the act of dreaming, is what being a practical sailor is all about.

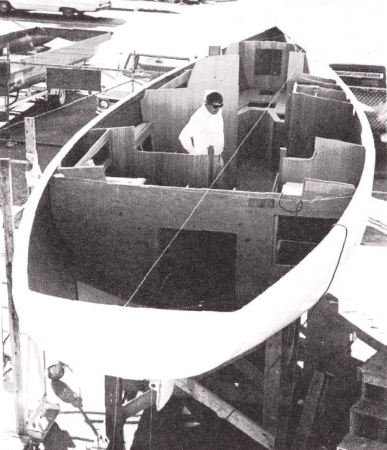

The Right Boat: Construction

About 30 years ago the wonderful chemical technology of fiber-glass made its debut on the production sailboat scene. Fiberglass was touted as «ending maintenance forever», and «indestructible, impervious to worm, rot, and corrosion». Fiberglass was the material that was going to free sailors from the slavery of annual maintenance.

Fiberglass has indeed revolutionized the boat building industry – in ways both good and bad. The low cost of petroleum-derived polyester and the relatively low level of skill involved in using it to build hulls compared to the skill required to build a conventional wooden hull, made the mass-production What size of boat do you need? What hull material?boat-building industry possible. Without fiberglass, it is safe to say that the phenomenal growth in the popularity of sailing in the last 30 years would not have taken place.

As with any new technology, a whole new set of boat building rules had to be created to take advantage of the wonder material. Seat-of-the-pants engineering has been the rule rather than the exception in fiberglass boat building. Part of the problem has been the properties of the material itself. A fiberglass hull layup consisting of layers of mat and roving has a remarkable combination of properties. However, coupled with these positive characteristics is a big negative one. Thin fiberglass panels, for all their strength, have all the rigidity of an inner tube.

A number of approaches to this problem have been taken over the years. Early fiberglass hulls were massively built, with hull skins almost as thick as the planking on a wooden boat of the same size. This achieved the required panel stiffness, but at the cost of inordinately heavy hulls and consequently, relatively low ballast-to-displacement ratios.

When oil cost three dollars per barrel, it was not too unreasonable to build a boat this way if you were willing to accept the trade-off of a heavy hull and slightly reduced interior volume. The interior volume of a heavy, solid hull layup was still far greater than a wooden boat with its complicated system of internal framing. In this day and age, however, this approach is a little extravagant.

The other approaches to achieving panel stiffness are:

- coring, either with end-grain balsa or lightweight plastic foam (Airex or Klegecell);

- internal stiffening with stringers or bulkheads;

- or stiffening with an internal molded liner attached to the hull.

All of these methods are used in production sailboats, and all work to achieve panel rigidity. There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages to each method.

Coring provides an insulating barrier between the inner and outer fiberglass skins, greatly reducing the tendency of glass to transmit heat and cold (a cause of condensation inside the hull). For a boat which is used either in the tropics or in a cold climate, a cored hull is highly desirable for its insulating properties.

Cored hulls also deaden the sound transmission of fiberglass and are stiffer for their weight than an uncored hull. They are not, however, without disadvantages. The hull layup is more painstaking and time consuming. Core materials are fairly expensive. In some cases, vacuum bagging must be used to insure a good bond between the core and the surface skins. Quality control in the hull layup is critical. Delamination of cored hulls is rare, but there have been lawsuits against builders alleging this type of structural failure.

The core material is usually cut out where fittings pierce the hull, or where major bulkheads or chain plates are to be bonded. The hours for these jobs add up to increase hull costs. A great deal of debate has centered on whether or not end-grain balsa absorbs water if a hull skin is punctured. For many years Lloyd’s refused to class balsa-cored hulls because of this fear. From our observations, balsa core exposed due to puncture or abrasion of a hull will slowly absorb water, and that water can migrate throughout the core. This means that you must promptly repair damage to a balsa-cored hull, whether the damage is above or below the waterline. It does not mean that balsa coring is unsuited for use below the waterline.

Plastic foam-core materials, notably Airex and Klegecell, are also used in production boat building, although far less frequently than balsa. The polyvinyl-chloride (PVC) foams have excellent structural properties, but are certainly more difficult to handle than a solid glass layup, and they are expensive. The difficulty and extra time spent in laminating the core material further increase the cost of a cored hull. Foam-cored hulls are exceptionally light and stiff, and the core will not absorb water in the event of a puncture of the hull skin.

More common in the US boat building industry in modern times has been the use of a relatively thin fiberglass shell with stiffness provided by a molded hull pan or liner,, or the bonding to the hull of internal components such as bulkheads and berth tops. The body pan or hull liner has been extremely popular. Major furniture components – cabin sole, settee fronts and tops, galley cabinets – can be molded outside the boat, greatly reducing labor costs. Good glass lay up is still faster and easier to do than good joiner work.

The body pan or hull liner is dropped into the hull, and is bonded to the hull shell wherever the liner touches the skin. The liner usually does not touch the hull in many places, and it is not possible to verify the degree of bonding of the liner to the hull. No matter how carefully done, attaching the liner to the hull is still a secondary bond, which develops less strength than a primary bond. (A secondary bond is any fiberglassing that is done to another surface after that first surface has cured.)

Bonding of a built-up interior of plywood panels to the hull has the same weaknesses as bonding a hull liner to the shell. Careful surface preparation – grinding and degreasing – is required to get a good bond between a wood bulkhead, its tabbing, and the hull shell. Local distortions of the hull may occur wherever interior components are bonded to it. These are visible from the outside of the hull in the form of «hard spots», subtle ridges that form along the hull where bulkheads or furniture are glassed in. Hard spots are not necessarily indicative of an excessively thin hull shell, but they are aesthetically displeasing and do not inspire confidence in the builder.

Many boat builders glass every internal component to the hull on the theory that the more you attach to the hull shell, the stiffer it will be. This is fine in theory, but in fact you rarely end up with reinforcement in areas that really need it, such as the broad, flat panels of the topsides aft of the bow.

In addition, calling the way in which much interior joiner-work is attached to the hull «bonding» is a misnomer. After the hull flexes for a few years, the «bond» often fails, increasing the unreinforced panel size, which increases flexing causing other secondary bonds to fail. It is not uncommon, on a five- or ten-year-old boat with this type of construction, to find that half of these secondary bonds have failed, even on lightly used boats from builders with a good reputation.

This type of failure does not mean that the hull is necessarily too weak, but it does imply an undesirable degree of hull flexibility. The classic example is the famous production ocean racer of the late 1960s which evoked the following catechism: Question: «How hard can you drive the boat?» Answer: «Until the berths pop out of the forward cabin».

Since we have heard a number of boats used as the object of this criticism, we will delete the names of the accused, not for fear of insulting the innocent, but for fear of neglecting the guilty.

All of these approaches to hull stiffening can work. The most important input in all cases is the care that the builder puts into construction. This frequently comes down to the degree of experience and the level of supervision of the foreman on the production line. Almost no one likes working with fiberglass, and it is not realistic to expect a $ 5-per-hour glass man to take care that all surfaces are neat and clean, that excess air and resin are rolled or squeegeed out, and that all the other steps are fully implemented to produce a light, monolithic hull.

For maximum strength, the resin-to-glass ratio must be carefully controlled. This means not only full saturation of the reinforcing fibers, but removal of excess uncured resin while the hull is being laid up. It is not possible to tell by looking at a completed hull if the layup is resin-rich or resin-starved, neither of which achieves full strength. Ideally, the plugs cut from the hull where through hull fittings are installed should be saved for the surveyor, who can have them analyzed for resin and glass content. Otherwise, you must rely on the skill of the boat builder, or more specifically, the skill of the men in the molding room. One trip into the molding room of a boat builder is enough to convince most people that hull layup is just about the nastiest job in fiberglass boat building.

Decks. Deck and cabin house surfaces are relatively flat. They are also fairly heavily loaded by being walked on, by the installation of gear for sail and ground tackle handling, and by lifeline stanchions and pulpits. A large percentage of the boats built today therefore have balsa-cored decks and cabin-house tops, which result in light, rigid surfaces. Because decks are nearly flat, construction of cored layup for decks and cockpits is far simpler than molding to the compound curves of the hull.

Balsa coring should be removed from the cabin top in the way of a deck-stepped mast to provide better compression resistance. It is also desirable to put solid coring – either solid glass or plywood – in other heavily loaded sections of the deck such as where cleats and winches are mounted.

It is common to see fairly sharp corners in some deck moldings, particularly in the cockpit. These areas should be well radiused, or the hinge effect of repeated flexing of the deck can cause cracking of the gelcoat.

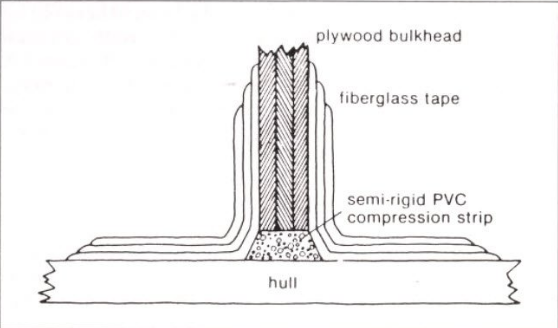

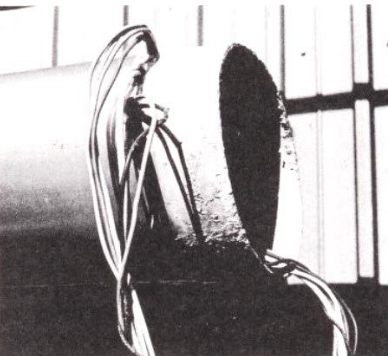

Joining Deck and Hull. Probably no single topic stirs up more partisan response and stubbornness than how the deck molding is attached to the hull molding. In the early years of fiberglass boat building, deck and hull were almost universally fiberglassed together. Although the exact technique varied widely, the general principle was to overlap the hull-to-deck joint with several layers of fiberglass cloth, in effect making the hull and deck one piece. Once again, this is fine in theory, but in practice it is still a secondary bond and therefore suspect. Thousands of hulls and decks have been joined in this manner, and the percentage of failures has probably been very small, but they can occur.

The subsequent variations on chemical bonding are almost infinite. There are inward turning flanges, outward turning flanges, coffee can lid flanges. Some are glassed together with cloth, others use polyester putty between the flanges, some back up the chemical bond with fasteners such as self-tapping screws or through-bolts.

Failure of a chemical bond in the hull-to-deck joint can be catastrophic, with complete failure of the secondary bond resulting. The classic story is of the boat which flexed so badly at sea during a delivery that the hull and deck began to separate. The skipper kept the two halves of the boat together by passing lines around the hull and tightening them with a Spanish windlass. Unfortunately, we have never seen one of those boats – the brand and model varies with the storyteller – that has experienced catastrophic failure in the course of normal use. We have seen hull-to-deck separation as the result of collision with other boats or impact with a dock. In most cases the break has been the result of a fracture of the secondary bond rather than the failure of either the hull or deck molding.

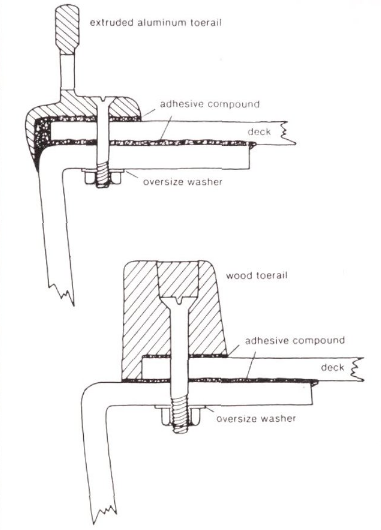

By far the simplest and strongest hull-to-deck joint is the inward-turning hull flange at deck level, with the deck laid over it and the two thoroughly bedded and through-bolted at close intervals. This joint can be covered by a wooden toe rail, whose through fastenings form part of the mechanical hull-to-deck joint, or it can be covered by an aluminum extrusion specifically designed for the purpose.

The use of a powerful adhesive bedding compound such as 3M 5200 gives this joint much of the strength of a chemical bond without its brittleness, and through-bolting at intervals of less than a foot-six inches is reasonable bolt spacing – effectively ties the two moldings together mechanically. Variations on this joint are becoming increasingly popular on everything from the least expensive boats to the most expensive.

It is not reasonable to condemn rigid chemical joints out of hand. Few boats ever find themselves in the position where hull and deck are strained badly enough to cause separation. However, for a boat designed for serious offshore or coastal use, whether racing or cruising, we prefer a through-bolted, flexibly bedded hull-to-deck joint.

Fiberglass hulls have revolutionized the boat building industry in the last 20 years, eliminating many trouble spots, but they are not a complete panacea. Skill and quality control are essential for the production of strong, long-lasting fiberglass hulls. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to judge the quality of the hull simply by looking at it. Builders consider hull layup schedules to be proprietary, and even if he had the schedule in hand, it would mean little to most boat buyers.

It is not normally possible to have a boat surveyed while it is under construction. Usually, you buy the boat off the dealer’s lot. Some builders refuse to have surveyors in their plant. In the case of an expensive custom design, the owner would be foolish not to have a surveyor’s opinion at various stages of construction.

Your best defense as a buyer of a production boat is to educate yourself as much as possible about construction and to ascertain the reputation of a boat or builder by talking to those who own the boats, not just to those who sell them. A survey of the boat at the dealer is always a good idea, before you accept delivery of the boat.

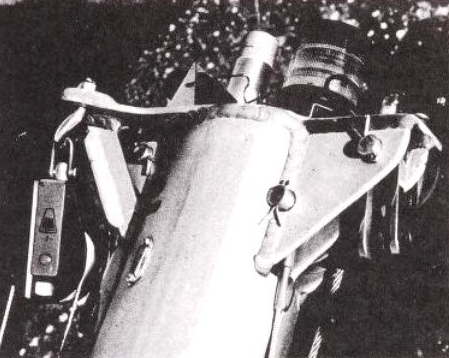

The Right Boat: Keels

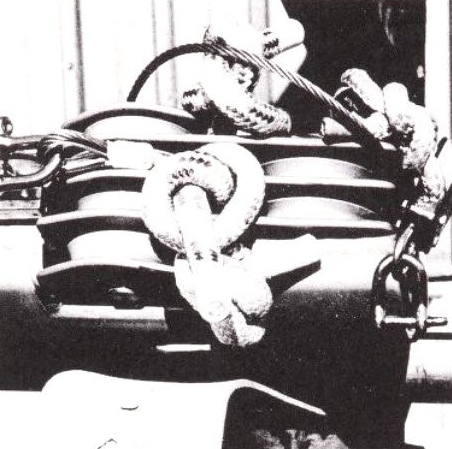

A ballast keel keeps the boat upright under a press of sail, takes the boat’s weight when she is hauled out, and is usually the first part to take the ground when the skipper makes a navigational error. This hard-working appendage has caused nightmares for designers and builders since Nathaniel Herreshoff and George Watson began hanging lead on the outside of their boats in the late 19th century. Attaching the ballast to the boat, and keeping it there, is one of the most basic of boat building problems.

There are two basic approaches to ballasting a Manufacturing of Fiberglass Boats and Design Featuresfiberglass boat. Ballast may be an external casting bolted to the hull, or it may be put inside a hollow keel that is part of the hull molding.

External Lead Keels. For a boat with a tall fin keel, the simplest solution is the external ballast casting bolted directly to the hull molding. In the round-bottom light-displacement boat, unfortunately, attaching the keel directly to the hull completely eliminates the bilges. Any quantity of water inside the boat can make life miserable by migrating to and fro as the boat heels or rolls, always out of reach of the bilge pump.

Some builders of fin-keel boats therefore construct a hollow keel stub, perhaps a foot deep or less, which serves as a sump. A shallow, hollow stub, even a very narrow one, can be laid up without too much difficulty.

Traditionally, bronze keel bolts were used with lead keels. In recent years even Hinckley, the ultimate bastion of conservatism, has gone to the use of stainless steel keel bolts. Stainless steel comes in many alloys which have widely varying properties of corrosion resistance. The fact that your boat has stainless steel keel bolts is not a guarantee that your keel will stay attached forever. Stainless steel is subject to several types of corrosion, some alloys more than others. The most insidious type of corrosion is the result of the steel living in a salt-saturated, low-oxygen environment like the underwater structure of a wooden boat. Theoretically this type of corrosion should not exist in a fiber-glass boat as long as the joint between the external ballast keel and the hull remains tight and both the top of the keel and the keel landing on the hull are well bedded.

If the keel-to-hull joint is cracked open or rust stains weep from the top of a lead keel, the stainless steel keel bolts are suspect. For this reason, when purchasing a new boat, it is a good idea to examine sister ships that have seen several seasons of use to check the condition of the keel joint. Corrosion of stainless steel keel bolts is only likely to be a problem in salt water or in heavily polluted fresh water, or if there is an electrical problem aboard the boat.

Most keel bolts consist of cast-in-place threaded stainless steel rods. In principle, when the lead is poured it fills in the threads, just as if the keel bolts had been tapped into a precast keel. In fact, it is unlikely that all the threads will be perfectly filled. To compensate for this, it is best to cast the bolts in place with nuts and washers on the lower ends of the threaded rod, to take the keel load if the poured-in connection between keel and bolt proves to be inadequate.

The hull should be reinforced in the area of attachment of an external keel due to the wracking forces exerted on the hull by a fin keel. This means a thicker laminate, transverse framing members (floor timbers of wood, fiberglass, or metal), or an internal load-bearing structure such as the Triaxial Force grid in Ericson yachts. A fiberglass hull which shows no obvious internal reinforcement in the way of the ballast keel is a boat to be wary of.

Lead keels are frequently delivered with finishes that are too smooth. A lead keel should be thoroughly sanded before the application of either fairing putty or bottom paint. This will remove surface oxidation and provide adequate tooth for the adhesion of paint and putty.

On a boat with a stub fiberglass keel with the lead attached below, the lead should be perfectly faired into the fiberglass stub. There is no excuse for a ridge or shoulder which will create needless drag.

External Iron Keels. Iron keels have problems all their own. Copper-based bottom paints cannot be used on iron keels without extensive barrier coating, which can break down in a few years. The coating can break down much quicker, of course, if the boat runs aground or grounds out at low tide in her slip, leaving you with a badly pitted, inefficient surface. The lower density of iron also means that an iron-keeled boat must have a larger keel volume – and consequently more wetted surface – in order to provide the same stability as a smaller lead keel.

Galvanized steel keel bolts are usually used with iron keels. These bolts are more susceptible to corrosion than more noble metals. Should the bedding compound between the top of an iron keel and a fiberglass hull fail to keep water out, heavy rust can build up on top of the keel, forcing it away from the hull and sometimes shearing the keel bolts or drawing them through the hull shell. Any heavily rusted iron keel is going to cause trouble as long as you own the boat.

New iron keels can be reasonably protected through the use of barrier coats such as epoxy bitumastic and the use of non-copper anti-fouling paints. It will be very difficult even on a new boat to keep a perfectly smooth racing finish on an iron keel in salt water.

Internal Ballasting. Given the difficulty of fairing, attachment, and the prevention of leaking, it would appear to make some sense to put the ballast inside the hull shell rather than outside. This is fairly common practice in boats of more traditional design – ones with relatively long, wide, shallow keels, as opposed to the deep, narrow keel of the modern racer-cruiser.

The modern fin keel sailboat would be extremely difficult to build with a molded fiberglass fin and internal ballast. Without wide, gently radiused garboards, the molders simply could not reach down into the keel cavity to lay up the shell. Functionally, if the keel will be much less than a foot wide and extend much more than two feet below the canoe body of the hull, an external keel presents far fewer hull construction problems than an internal keel.

For boats of traditional design with hollow garboards, the use of ballast inside the hull shell is relatively straightforward. A molded keel cavity can be filled with lead shot, lead pigs, a single lead casting, random blocks of lead, or what have you. The «what have you» can cover a multitude of sins:

- boiler punchings in cement;

- steel reinforcing rod;

- scrap iron.

None of these «what have yous» have anything like the density of lead and can therefore offer only a fraction of the stability of a piece of lead of the same volume. It is fairly easy to tell if ferrous material has been used for ballast. A strong magnet passed over the outside of the keel will quickly answer the question.

Whatever material is used for inside ballast it must be thoroughly fixed in position in the keel shell. This is usually accomplished by filling the voids around the ballast with thickened polyester resin, a process which may need to be done in stages to prevent warping of the keel shell from the heat generated as the resin kicks off. If the keel shell yields at all when pressed on firmly, the ballast may not be firmly held in place.

With the ballast bonded in place, the top of the ballast and the garboard area of the hull shell is usually glassed over, in effect creating a double bottom. This should keep water out of the hull should the keel shell be damaged from grounding. Don’t let this lure you into a false sense of security, however. Frequently a deep keel sump is left in the shell behind the ballast, and if this very vulnerable section of the keel molding is torn open by grounding, the fact that the top of the ballast is sealed in does not mean much in terms of keeping water out of the boat.

Damage from grounding is the real danger of internal ballasting, and is one of the most frequent problems with any sailboat. For all its strength, the abrasion resistance of fiberglass is extremely low, and even an inch-thick fiberglass shell can be ground through after a few hours of pounding on rocks or coral. We have seen keel shells so abraded that the internal ballast has fallen through the bottom of the boat. It may take major damage to cause a single lead casting to fall out, but loose shot or lead pigs can fall through a small hole in the bottom. Repair of a damaged keel shell is covered in Chapter One of Volume III, Maintenance and Repairs.

Despite the potential for problems there are advantages to inside ballast:

- Barring serious grounding, the hull should remain watertight with no keel bolts or ballast seam to leak.

- Thickening the hull shell in the garboard area usually provides adequate support for the keel without additional reinforcement.

- A massive, hard-to-handle ballast casting is not necessary.

Some blue water sailors consider it ironic that many boats touted as world cruisers carry the ballast inside a molded keel shell. The long-distance cruiser may operate in poorly charted waters, under all conditions, and far from haul-out facilities. The cruiser is more likely to run aground, and more than any other boat can take advantage of the external lead keel. Nevertheless, we would probably not turn down an otherwise suitable design that was internally ballasted. Good boats are hard to find; the perfect boat is rarer still.

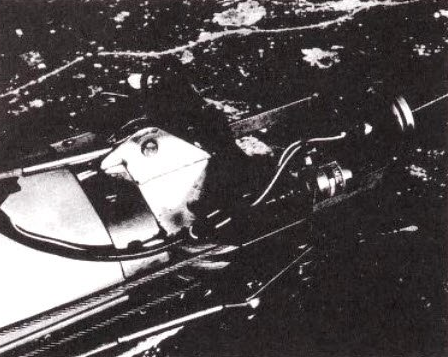

The Right Boat: Decks

The one-piece molded deck, cockpit, and cabin trunk is one of the great revolutions of modern boat building. The owner of a wooden boat learns to accept the inevitability of water coming through both the bottom and the top of his boat. With a molded fiberglass deck, there is little or no excuse for leaks, and the dream of a dry berth should be a reality.

The decks of early fiberglass boats were solid layups, and the broad, flat deck expanses were frequently as bouncy as a trampoline. The advantage of cored deck construction quickly became obvious, and today the majority of deck moldings on boats over twenty feet or so are cored, either with end-grain balsa or with plywood.

There are advantages to balsa coring, notably good stiffness fora given panel weight, the ability of balsa to follow compound curves, and good sound and thermal insulating properties. The only disadvantage to balsa coring is that a balsa sandwich has slightly less flexural and compression strength than a fir plywood sandwich. At the same time, the balsa sandwich is significantly lighter.

Foam coring is rarely seen in decks except in custom boats. Airex, because of a tendency to soften at fairly low temperatures, is not normally used in deck construction even in custom boats.

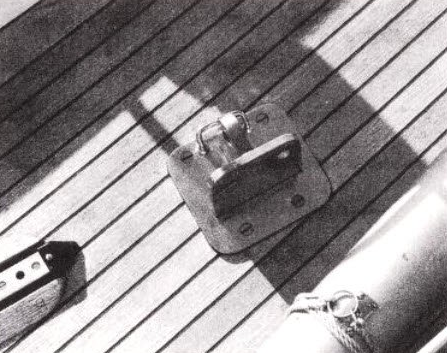

Mounting of Hardware. Since balsa is inferior to plywood in compression strength, it is common practice in balsa-cored decks to core the deck with plywood in areas where heavily loaded deck hardware will be mounted. The only time this presents a problem is when you decide to mount new hardware in portions of the deck that are cored with balsa. In a finished boat, it is simply not practical to recore sections of the deck. If large load-distributing plates are used, it is probably reasonably safe to mount hardware on balsa-cored sections of decking. On boats with stainless steel hardware fastenings, these backing plates should be aluminum sheet. On boats with bronze hardware and bronze fastenings, the load-distributing plates would ideally be bronze, although a plate of dense wood such as oak, used with oversized washers, is a reasonable substitute.

When mounting hardware on a deck cored with wood, it is a good practice to drill the bolt holes very slightly oversize, and dribble epoxy or polyester resin through the hole to coat the exposed core. If carefully done, this will help to keep water out of the core in the event of failure of the bedding compound under the hardware.

All deck hardware should be carefully bedded. Too much compound is better than too little. The ideal bedding compound would stay flexible indefinitely but not be so tenacious that removal of the hardware is impossible. This requirement precludes the use of polyurethane sealants, which are such powerful adhesives that you can easily damage the deck while trying to pry off a piece of hardware. Silicone and polysulfide sealing compounds are probably best for bedding deck hardware on fiberglass boats, although polysulfide sealant is also a fairly powerful adhesive.

In production boat building, it is common to mount as much hardware as possible on the deck molding before it is attached to the hull. This saves a lot of time on the production line, but it can create problems for the owner. Access must be provided to the back of every piece of through-fastened hardware on either the deck or the hull. If hardware is mounted after the deck, hull, and liner are joined, this is not usually a problem, but it does require foresight. A surprising number of boat-builders overlook this seemingly obvious requirement.

When buying a boat, note the locations of deck hardware, then go below to see if you can get to the back of each piece. If the nuts are inaccessible, someday that is going to mean trouble. Murphy’s law states that the less accessible a piece of hardware is, the more likely it is to leak or need replacement.

Hardware Quality. Most US boats use hardware of good quality. There is probably little difference between Nicro Fico, Schaefer, Merriman, Harken, or the other standard brands seen on production boats, although there are unquestionably specific pieces of gear made by each company that are superior to those of the competition.

While general quality may not vary greatly between brands, the way it is utilized by different boat builders can vary substantially. It is more likely that stock-boat hardware will be on the smaller and weaker side. The tendency to under size gear is particularly pronounced in choosing winches. Almost invariably, if the builder offers a winch package with more powerful gear as an option, the standard winches will be barely adequate for the boat. It is ironic that the racing boat with her gorilla-sized winch grinders will have winches two or three times as powerful as those on the cruising boat sailed by a middle-aged couple.

Deck hardware on imported boats is frequently inferior to that on boats built in this country. Far-Eastern boats in particular have long had a reputation for using hardware of poor quality, and despite a great improvement in recent years, that criticism is still generally valid. It is becoming more common for Far-Eastern boats to offer name-brand hardware as an option, and it is usually worth paying the price.

On the typical production sailboat, the quality of the hard-ware is usually less a problem than where or how the item is installed. For example, properly mounted bow chocks have almost disappeared. The closer the chocks are to the stem of the boat, the better they are likely to function in terms of holding the bow of the boat into the wind at anchor. The purpose of bow chocks is to provide a smooth, fair lead for anchor rodes and mooring lines. Without bow chocks – and a surprising number of boats lack them – a modern boat with high free board forward and relatively light displacement is almost guaranteed to sail around on her anchor.

Stern chocks are just as useful as bow chocks, particularly if a boat has wooden toe rails that could be abraded by dock lines. Midships chocks are also handy for spring lines.

Anchor Wells. The fore deck anchor well is one of the great innovations of the modern production boat. While carrying a lot of weight forward will increase a boat’s pitching movement, most boats with moderate forward overhangs can carry a working anchor and rode in a fore deck well without serious problems. Stored in a fore deck well, the working anchor is always close at hand yet out of the way. Spare anchors and rodes can be carried elsewhere, preferably low and toward the middle of the boat.

Large quantities of chain, however, should not be carried-in a fore deck well. While 200 feet of 1/2-inch nylon weighs only 14 pounds, 100 feet of 5/16-inch chain (a reasonable substitute for 200 feet of nylon) weighs 115 pounds.

Foredeck wells should have provision for attachment of the bitter end of the anchor rode. Usually it is not too difficult to mount a heavy eyebolt in the well if the builder has overlooked this item.

Anchor wells should be self-draining with scuppers large enough not to be clogged with mud from the anchor. The well should not drain into the bilge and should be completely sealed off from the interior of the boat. The well’s lid should have strong hinges and a positive provision for latching. Weak hinges and latches are common faults.

Any electrical wiring in the foredeck well – typically for running lights – should be secured under the deck with cable straps to prevent its being damaged when handling ground tackle. Splices and connections should be taped over and sealed with silicone.

While fore deck wells have made ground tackle handling and storage easier, they have complicated the mounting of fore deck cleats. Rather than paired cleats mounted near the centerline, it is more common to see port and starboard bow cleats shifted outboard almost to the rail to clear the lid of the anchor well. This is a reasonable solution, although sometimes leads from the bow chocks will run afoul of the bow pulpit stanchions if cleat placement is not carefully considered.

Pulpits and Lifelines. Bow pulpits are a good place to mount running lights. The simplest running light arrangement is the new international-style bicolor attached to the bow pulpit on the boat’s center line. This minimizes alignment problems, avoiding overlapping port and starboard sectors or blind spots for oncoming vessels. Running lights mounted on the pulpit will, however, be vulnerable to collision damage.

Running lights recessed in the hull are a poor idea. They invariably leak and short out, and their position close to the water almost guarantees that they will be invisible to boats on your leeward side.

Bow and stern pulpits, like lifeline stanchions, should be through-bolted and have substantial backing pads. Frequently, the underside of the deck molding is rough and irregular where stanchion and pulpit fastenings pass through. This creates problems when installing backing plates as it may not be possible to make the backing plate lie flat against the underside of the deck, particularly if the fastenings span the flanges of the hull-to-deck joint. Split plywood backing pads, distorted aluminum plates, and cracked fiberglass backers are frequently seen where an irregular interior surface exists under deck hardware. This can over stress fasteners or unevenly load decks, with gelcoat stress fractures a common result. This particular problem can frequently be remedied by the owner (see pages 134-139 of Volume IV, Do-It-Yourself Improvement Projects).

With boats getting wider, shrouds have moved inboard to keep head sail sheeting angles narrow enough for good upwind performance. This can either complicate or facilitate access to the fore deck. If the shrouds are moved far enough inboard, it is usually easiest to go forward by passing outboard of the shrouds. If, however, the shrouds are close to the lifelines, there may not be enough room outboard to get around that way, but the shrouds may be too far inboard to easily go between the shrouds and the cabin trunk. Easy access to the fore deck is necessary for head sail changing, docking, and the handling of ground tackle.

Handrails. The typical fiberglass sailboat has wood grabrails mounted along the outboard edge of the cabin trunk. These should be more than just an attractive way to visually break up a bleak expanse of white fiberglass. Handrails should be through-bolted to the top of the cabin. Merely screwing up into the rails through the coach roof is not adequate. Screws have relatively little holding power in tension, and the upward and outward pull you put on handrails is largely tension.

While handrails make a convenient lash down point for anchors, boat hooks, or even the dinghy, this is a poor practice. Things lashed to the rail may well interfere with its primary function: something to hang onto in heavy weather.

It is not a bad idea to have handrails running the full length of the cabin trunk. They can then be used as foot braces when working around the base of the mast as well as handholds when moving along the deck.

Head sail Track. Many production boats use an L– or T-shaped aluminum extrusion to serve as both a bolting flange for the hull-to-deck joint and a sheeting location for headsail snatch blocks. The disadvantage of this system is that in order to change headsail leads the snatch block must be unsnapped and shifted to the next hole in the toerail extrusion. With a sliding car on a T-track, headsail leads can be shifted when the block is under load, an important consideration for the racing boat.

A track that follows the sheerline results in a constantly changing sheeting angle relative to the boat’s centerline, making optimum upwind trim difficult to attain. For a cruising boat whose shrouds are at the outboard edge of the deck, this problem is not serious. For the racing boat with shrouds set in from the edge of the deck, an inboard track is a must for good upwind performance. Fortunately, track can frequently be added after construction, provided the deck is strong enough and good load distribution can be attained with oversize backing plates.

Whether you have a toerail-mounted track or an inboard track, be sure that it extends far enough fore and aft to allow effective sheeting of all overlapping headsails. Remember that the height of the jib’s clew off the deck greatly affects the fore and aft sheeting position. By giving your sail maker the length and location of your track, he can design the leech length to accommodate the track for sails of different overlap.

Headsail track must be through-bolted and should have either backing plates or oversize washers. If gelcoat cracks develop around the track, the deck is not strong enough to take the load, and you will either have to put still larger load-distribution pads under the deck or actually reinforce the deck structure. Headsail track fasteners are a common source of deck leaks due to the heavy loads imposed on them. If you develop such a leak, remove the offending bolt and rebed it. If this does not work, the whole track will have to be removed and rebedded. Check the bolts periodically for tightness.

Deck Surface. Secure footing on deck is critical. Most boats have molded-in nonskid, which varies in type and quality. Good nonskid should give secure footing when the decks are wet, be easy to clean, and be reasonably non-abrasive. These demands may be mutually exclusive. The decks of some boats, for example, are just about as nonskid as possible, but they are abrasive enough to wear through foul weather gear or water-softened skin in a short time.

Stark white is not a good color for decks and cabin tops. On sunny days, it is guaranteed to give the helmsman a headache from glare. Light tan, green, or blue are easier on the eyes without absorbing inordinate amounts of heat that might make the cabin below uncomfortable.

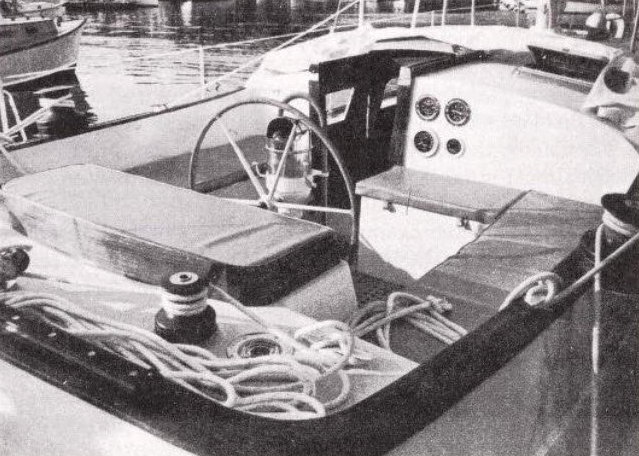

The Right Boat: Cockpits

The average sailor probably spends more hours in the cockpit of his boat than he does below. It is therefore ironic that below decks layout and decor have become the main selling points of most production boats, while the cockpit frequently seems to be considered an afterthought.

Like the interior, the design of the cockpit must meet demands that may be mutually exclusive. The cockpit should be roomy and comfortable in port for lounging and entertaining, yet it must be reasonably small if the boat is to do any offshore sailing. It should be laid out efficiently for the racing crew, yet with winches and sheets arranged so that the helmsman can run the boat when sailing shorthanded.

Given the fact that all these things may not be possible to attain in one boat, you must determine how the boat is to be used before deciding what arrangement works best for you. This may require some painful self-examination. The minuscule footwell with deck-level seating may be the right answer for single-handing in the Roaring Forties, but if you are going to be plugged into the dock most of the time, then a large, comfortable cockpit which accommodates six at the cockpit table may be the answer. At the same time, if long-distance cruising is in your future, a cockpit that seats ten people and is so wide that you cannot brace yourself against the leeward seat from the weather side is not the right answer.

The Offshore Cockpit. For serious offshore sailing, the cockpit should meet the standards in the Special Regulations of the Offshore Racing Council for Category 1 racing.

Category 1 racing is defined as: «…races of long distance and well offshore, where yachts must be completely self-sufficient for extended periods of time, capable of withstanding heavy storms and prepared to meet serious emergencies without the expectation of outside assistance». If you substitute the word cruises for races, that sentence is an excellent definition of off-shore cruising.

Seaworthiness is the prime consideration of the offshore cockpit. The concept is to minimize the amount of water that the cockpit could hold in heavy weather, keep that water from getting below decks, and facilitate its return to the sea.

The volume in cubic feet of the cockpit of the ocean-going yacht should be no more than 06L × B × FA according to the Offshore Racing Council. While «L», «B», and «FA» are hull dimensions measured under the IOR, a reasonable approximation for the cruising boat can be derived by substituting your boat’s waterline length for L, her beam for B, and the freeboard at the corners of the transom for FA.

As an example, take a modern cruiser 36 feet on deck with a 29-foot waterline, a beam of 11,5 feet, and freeboard aft of three feet. The formula yields an allowable cockpit volume of 60 cubic feet. Note that this is the volume of the cockpit below the lowest coamings. A cockpit with side coamings but no coaming aft has considerably less volume than the same cockpit which is enclosed by a coaming across its after end.

For coastal or lakes sailing, the ORC-allowable cockpit volume is 50 percent greater. In all cases, the cockpit sole should be at least 02L above the waterline. This amounts to seven inches in our hypothetical 36-footer.

Cockpit Scuppers. Proper cockpit drains are a critical requirement. As a minimum, a cockpit meeting the ORC volume requirements should have two drains with no less than 1-1/4 inches inside diameter each. Grates or screens over drains greatly decrease the water flow, so the size of the drains must be increased if there is any restriction over the opening.

Cockpit scuppers should drain at any angle of heel. Surprisingly, many do not. This problem is most acute where the cockpit extends aft almost to the transom – a typical arrangement in the modern racer-cruiser with little or no after deck. In such boats, the cockpit sole should pitch down toward its forward end, and the drains should be moved to the forward corners of the cockpit.

Since cockpit scuppers inevitably are near the waterline, they should be fitted with sea cocks. Double-clamped, non-collapsing flexible hose is the best material for cockpit drain plumbing. The flexing of hull and cockpit could fracture rigid plastic or fiberglass piping.

The Bridge deck. In an attempt to maximize cockpit size and below decks accessibility, many boat builders have eliminated the bridge deck. Frequently the companionway sill is raised a few inches above the cockpit sole to keep water in the cockpit from getting below. This is a poor arrangement for any boat which contemplates serious cruising. A bridge deck reduces cockpit volume, serves to increase below decks space (usually over galley counters), and is invaluable in keeping water out of the cabin. With a deep companionway, the temptation to leave lower drop boards out for the sake of convenience is simply too great and is an un seaman like practice.

For all categories of racing – coast wise, as well as offshore-the Special Regulations require that companionways extending below the level of the main deck be blocked and secured to at least that level. In many production boats, this means leaving half the drop boards in place when sailing.

Another questionable practice is the use of wide companion-ways with sharply tapered sides. While tapering the sides of the companionway makes it easier to remove and insert drop boards and facilitates getting below, it also makes the boards more likely to fall out in a severe knockdown. In any case, drop boards must be fitted with latching devices such as barrel bolts or slide bolts to positively secure them.

The use of hinged doors rather than drop boards is a poor practice in small boats. Doors require the companionway to be completely opened to get on deck or below, and they are easily torn from their hinges.

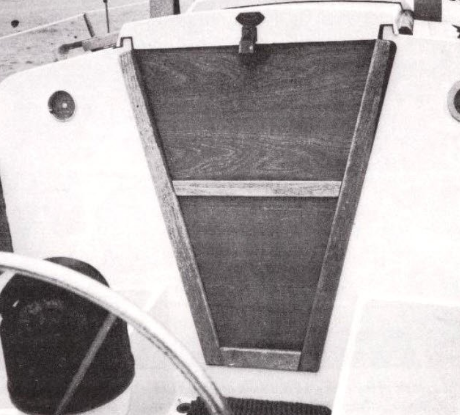

Protecting the Companionway. For offshore sailing, a companionway sea hood – basically a box protecting the front of the companionway slide – is a must. Water driving under the forward edge of an unprotected slide can make below decks a rain forest in short order. A serious cruiser, whether sailing coastwise or offshore, will find the sea hood worth its weight in gold.

Sea hoods frequently incorporate a molded spray rail which may extend across the top of the deckhouse to form a dodger coaming. Without some form of coaming, a cockpit or companionway dodger’s efficiency is severely limited. Even if it is pierced for sheets and halyards leading aft along the coachroof, a properly designed coaming will go a long way toward keeping water from driving under the lower edge of the dodger.

Cockpit dodgers are rapidly becoming standard items on boats used in cooler climates. While a dodger limits visibility and adds windage, the trade-off in protection of the forward end of the cockpit may well be worth it. If a boat tends to be wet, has low coamings, and a low cabin trunk, a dodger can make the difference between comfort and misery in bad weather. In a boat whose cabin bulkhead slopes forward, the dodger also makes it possible to leave the companionway open for ventilation when it is raining.

Dodgers should be custom-fitted to the boat to be sure that they do not interfere with winches, sheets, halyards, the main boom, and seating at the forward end of the cockpit.

Cockpit Lockers. Improperly designed cockpit lockers are a common problem. Cavernous, undivided space under the cockpit is practically useless. In boats with a quarterberth, there is frequently a shallow cockpit locker over that berth. This is handy for small items such as spare blocks and sail ties. Usually, the other side of the cockpit will have a huge locker euphemistically dubbed a sail locker. Unless the locker lid is also huge, chances are that nothing larger than a carefully folded storm jib will go through the opening. Chances are also good that screws, exposed bolt heads, and cables lurk inside the locker to rip holes in your new triradial spinnaker.

The cavernous locker may hold large quantities of junk, but whatever item you want is guaranteed to be at the bottom of the heap under the barbecue and the storm anchor. You can make a big locker more useful by subdividing it with plywood or net partitions, installing hooks for spare sheets, generally organizing so that nothing must be piled in. If the cockpit locker provides access to the steering gear or stuffing box, make sure that your partitions are easily removable in an emergency.

An amazing amount of water can get below through leaking cockpit locker lids. The lids should be gasketed, have positive dogs, and have scuppers that will allow water to drain from the leeward cockpit seat with the boat heeled over 30 degrees.

Seating. It is unfortunate that people do not increase and decrease in size depending on the size of their boats. If you want cockpit seats on which you can lie down, they must be six feet long whether your boat is a 25-footer or a 45-footer. The cockpit on a small boat invariably takes up a greater percentage of the boat’s total volume than the cockpit of a larger boat. Seating simply does not scale down.

In order to have coamings high enough to offer any real back support, the cockpit seats must be sunk below the main deck level. The footwell must be lowered correspondingly. This, of course, increases the cockpit volume.

Ideally, the cockpit seats should slope downward outboard, and the coamings should angle outward. This provides more comfortable seating, but it makes it more difficult to use the seats for sleeping, and renders it impossible to have the bridge deck at the same level as the cockpit seats. Therefore, what is gained in comfort is lost in convenience. In any case, a gutter or scupper must be provided at the outboard edge of the seat, or those seated to leeward will suffer from wet-seat syndrome.

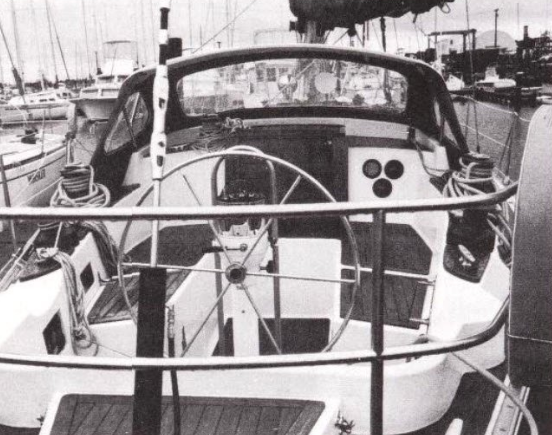

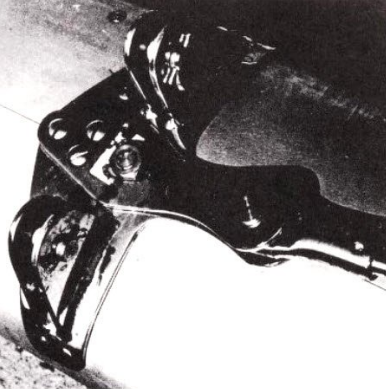

Steering. The pedestal-type wheel has become almost universal in boats over 30 feet. Although this steering system generally creates more room in the cockpit, it is more expensive, less rugged, and more prone to failure than a strong, simple tiller. While a tiller takes up cockpit space, it is generally preferred for its sensitivity by racing sailors graduating up from small boats.

Placement of a wheel steerer can be problematic. Some prefer the forward end of the cockpit for shelter under the dodger and accessibility to sail controls. Others prefer the aft location to free up the forward end of the cockpit for sail trimmers and guests. For shorthanded cruising, the forward location is better. For racing, an aft position is probably preferable.

While you rarely sit directly behind the wheel when sailing, most boats with the wheel aft have a seat across the rear of the cockpit for the helmsman. This seat should be either concave or convex to provide a secure seat with the boat heeled 20 degrees. If the boat has a high cabin trunk, a convex seat may help a short helmsman see forward. With a flat seat, the helmsman invariably slides to leeward.

If you like to steer from the windward or leeward rail, be sure that the wheel is large enough in diameter to be easily reached from the rail. This may require notching out the cockpit sole for the wheel on larger or exceptionally wide boats. Obviously, a wheel well must not extend below the waterline, and must be scuppered overboard.

Unless the cockpit coamings are wide and flat on top, the helmsman may not be able to sit outboard. The best solution to this problem is found on the Tillotson-Pearson Alden 44, which has a concave area in the top of each coaming for the helmsman’s rear end.

Sheet Leads and Sailhandling. Efficiency in sailhandling must be a major consideration of cockpit design. Winches must be placed so that handles can be cranked through 360 degrees without striking the dodger, life-lines, stanchions or pulpit. If the coamings contain molded-in winch islands, be sure they are large enough to accommodate bigger winches. We have never seen winches that were too large for the short-handed sailor.

The placement of the main sheet traveler invariably causes problems. If you put the traveler on the bridge deck, it limits access below. Put it behind the helmsman, and the main sheet loses efficiency by pulling aft as well as down unless the boom is very long. An aft location for the traveler also tends to decapitate the helmsman, and requires putting the main sheet trimmer in the end of the boat, where his weight does the least good.

Put the traveler on a bridge over the companionway, and you may render it impossible to fit the boat with a dodger. Move it forward of the companionway and the sheeting becomes inefficient unless the boom is very short. All things considered, that location on the bridge deck starts to look pretty good.

Engine Controls. With pedestal steering, engine controls should be mounted directly on the pedestal. With a tiller or worm-gear wheel, mounting them on the side of the cockpit makes sense. Since most people are right-handed, the right side of the cockpit is usually the best location.

Throttle and clutch controls are notorious sheet catchers. Some boats therefore move these controls inside a cockpit locker. This can create problems operating under power in rain or heavy weather, compromising the watertight integrity of the cockpit if the locker must be kept open to operate the engine.

The instrument panel should be within sight of the helms-man when seated at the normal under-power steering position. An excellent idea is recessing the panel into the face of the bridge deck. All panels, despite claims of watertightness, should have protection from heavy spray. The panel should not be so close to the cockpit sole that it can be shorted out by a few inches of water in the cockpit.

Sailing Instruments. The aft cabin bulkhead makes a reasonable place to mount instruments, although it means that loungers at the forward end of the cockpit will probably block the instruments just when you need them most. Unless the steering position is very far aft, the ideal location for instruments is in a pod mounted atop the companionway sea hood. The instruments will be just about at eye level, so that the helmsman can see them without having to glance down and no unsightly holes will have to be cut in the main bulkhead.

Center Cockpit: Yea or Nay?

Center cockpits were a highly popular fashion of the early 1970s epitomized by the Morgan Out Island 41 although larger boats, especially those called motorsailers with cockpits well forward, had a measure of popularity for many years before that. Having a cockpit forward offered three claimed advantages over the aft cockpit:

- more appealing interior space, notably the privacy of fully separated cabins;

- a larger engine compartment;

- and a drier, more comfortable location for the crew under sail with better visibility forward under power.

The last argument cites the height of the cockpit above the water for dryness, and its closeness to the center of the boat for less motion as the boat pitches.

Partially offsetting these claimed advantages are several drawbacks of the center cockpit. The weight of both the deck structure and the crew is located comparatively high:

- raising the boat’s center of gravity and reducing stability;

- the broken-up accommodation plan may reduce interior space;

- the need for interior access to the after cabin to avoid having to use the exposed cockpit;

- the lack of visibility under sail;

- and the impression that the high top hamper does indeed make the boat appear top heavy.

It is, of course, an axiom of yacht design that interior space can only be achieved at the expense of sailing performance and traditional aesthetics. Yet virtually since the start of the boom in auxiliary sailboats in the early 1960s it has been the customers’ desire for livability that has dictated the design of production boats. It may or may not be true that designers have first drawn the interior, then wrapped that interior with a hull shape regard-less of what shape that wrap becomes. Certainly headroom, numbers of berths, ample stowage space, a functional galley, an enclosed head (or two) often with a shower, and an eating facility with the proportions of a dining room have all been priorities among buyers enjoying – and supporting – that boom.

Eventually, the demand for center cockpit boats fell off, to some extent paralleling the decline in the threat of an energy crisis that had made sailboats with the amenities of powerboats so popular. By the early 1980s, there were few being built, and of those, almost none that were not optional variations on boats offered with the traditional aft cockpit layout.

There is no better example of the fundamental compromise between sailing qualities and living qualities than the center cockpit boats, at least those below 40 feet or so. Over that size, the compromises can become less, increasingly so with added length. At 50 feet or so, a center cockpit can be incorporated with few of its inherent drawbacks. The cockpit can actually be at or below deck level, the engine needs the space it gets, and fore and aft access below is not a factor. At the same time, though, there are many ways to obtain privacy in larger boats, so the complete division of sleeping units with a divided layout may not be the most feasible answer.

No cockpit layout can solve all the problems of the racer, cruiser, and day sailor. Nonetheless, the needs for safety, comfort, and functionality are universal. The next time you look at a boat, consciously resist the urge to plunge below into the world of teak and plush upholstery; sit for a while in the cockpit. Imagine the boat rail-down going to weather in a fresh breeze. Imagine half a dozen friends gathered in the cockpit for a party. Imagine yourself and your spouse alone on a thousand-mile passage. Forget the interior decor until you find out if the cockpit works for your kind of sailing.

The Right Boat: Belowdecks

In the last 30 years, few aspects of the small cruising boat have changed more than the interior volume. When the Triton first appeared in the late 1950s, the fact that a 28-footer could have full headroom was seen as a major breakthrough. The Paul Coble-designed Corsair of a few years later brought full headroom to 24-footers. Ever since, interior design has loomed larger in importance in boat building and design.

Part of the gain in interior volume is due to the change from wooden construction to fiberglass. A wooden boat with a beam of 10 feet will sacrifice at least six inches of interior beam to the thickness of her planking, frames, and ceiling. A fiberglass boat of the same beam could lose less than an inch. Considering the small volume of the interior of a boat, those few inches add up to an amazing amount of space.

The same analogy applies to headroom. The wooden boat, with its deep floor timbers and deck beams overhead, sacrifices a lot of headroom to accommodate the basic components of the boat’s structure.

In addition, for a given overall length, sailboats have grown wider and longer on the waterline. For example, take the Bristol 27, a popular small cruiser of the late 1960s. On a length overall of 27 feet, two inches, the Bristol has a beam of eight feet and a waterline length of 19 feet, nine inches. Displacement is about 6 500 pounds.

While those dimensions were pretty reasonable 15 years ago, they look pretty skimpy today. Compare the Bristol 27 to the Tanzer 27, a typical small racer-cruiser of today. On a length overall of 26 feet, seven inches, the Tanzer has a beam of nine feet, six inches and a water line length of 22 feet, 6 inches. Her displacement is about the same as that of the Bristol.

The Tanzer is a dramatically larger boat in interior volume, and typifies what has happened to boat design since the 1970s. For a boat of the same length, today’s buyer demands—and gets – more interior volume. Despite the gain in volume, the interior layout has changed relatively little. In boats from 25 to 40 feet, the most common interior arrangement still consists of a double cabin forward, the head next aft with lockers opposite, a main cabin with settees parallel to the center line, a galley, and perhaps a quarterberth aft.

Obviously, the amount of headroom, elbow room, and leg room varies dramatically when you have the same general arrangement on boats that range from as little as 5 000 pounds to to as much as 20 000 pounds of displacement.

Privacy. When there is more than one person aboard a boat, privacy rapidly becomes an issue. Whether it is dressing, using the head, or sleeping, most sailors have the occasional desire to separate themselves physically and psychologically from their fellow crew members. This issue is not critical, of course, in a boat used for day sailing. Most of us are capable of putting up with almost anything for a few hours. Granted, a cedar bucket in the middle of an open boat has little to recommend it when sailing with a mixed crew, but generations have managed with little permanent loss of dignity.

However, when cruising for any period longer than overnight, some privacy is almost essential. When you look at a boat, think what it will be like aboard her for a long weekend or a week’s cruise in the rain. Then think about those six berths in a 30-footer and see if you really want to cruise with them all filled. Then you may find the flaw in the question, «How many does she sleep?»

Down the Hatch. With that in mind, it is time to go below. Is there anything to grab on to when coming down the companionway ladder? Is the ladder so steep that you must go down facing the ladder or can it safely be descended like a stairway?

Steep ladders are not necessarily bad, but they must have provision for something to grab onto in a seaway such as handholds cut into the sides of the ladder, or grab rails on the inside face of the companionway. Needless to say, the ladder should be positively attached to the boat. At the same time, if it is necessary to remove it in order to get to the engine for service, there must be a simple way to unlatch the ladder and move it out of the way.

The Forward Cabin. Having negotiated the companionway, move all the way forward to the forward cabin. Every boat from 22 feet up has a «V-berth in the forward stateroom». Some of the worst travesties of design are foisted on boat buyers in the name of that private forward cabin.

First of all, let it be understood that a V-berth is not a sea berth. If you intend to do sailing that requires sleeping aboard while underway, pretend that the forward berth does not exist; it will be unusable in any weather other than a flat calm. In fact, consider everything forward of the mast to be a bit of a twilight zone at sea, the part of the boat that you don’t venture into unless you have to. The motion in the forward third of any boat much smaller than 50 feet when beating into a head sea has to be experienced to be believed. You quickly learn that only the toughest sailors sleep forward except in port.

For cruising, you may find it better to have storage forward than sleeping accommodations. This will run you right up against the layout of almost every production sailboat. That is why unusual interior arrangements, such as that of the Nonsuch 30, really catch our eye. In a boat designed for two people, you just don’t need to waste that space forward for sleeping. If you want a double berth, it is usually possible to modify a main-cabin settee to serve the purpose.

For occasional cruising with children or another couple, the forward cabin may be the right answer. Most sleeping, after all, is done at anchor or at the dock when the forward location is perfectly acceptable.

Given the reality of the forward V-berth, what should you look for? Inevitably, the berth is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. Lie in it with someone else and see if the two of you can really be comfortable with your legs entwined.

Until a few years ago, there was inevitably a space at the forward end of the V-berth labeled an anchor locker. Unfortunately,in order to use any ground tackle stored there, you had to drag it out over the berth and up the forward hatch, knocking mud all over your cushions. The smell and mess of ground tackle stowed forward did little to make that cabin more comfortable.

Somewhere along the way someone came up with the idea of the fore deck anchor well. Whoever put the first fore deck anchor well on a production sailboat will, if he can be discovered, be awarded The Practical Sailor’s award for «Best Invention of the Last 20 Years».

There is likely to be a large empty space under the V-berth. Since space on any boat is at a premium, something must be done to utilize it. One thing that is frequently done, but which really has little to recommend it, is to install a large water tank in the space. Unfortunately, under the V-berth forward is one of the least desirable locations for a water tank. If a boat pounds in seaway, much of that impact is going to be taken on the section of the hull directly under the V-berth. Any tank mounted there must be absolutely rigidly attached to the hull and must be extraordinarily strong. Many forward water tanks have either split or come adrift when a boat pounds her way to weather. It is most unpleasant to discover that your fresh water supply has been transformed into bilge water.

More serious than the installation difficulty is the effect on the trim and handling of the boat with a large weight far forward. A gallon of fresh water weighs nearly ten pounds. Put even a 20-gallon tank forward on a 30-footer, and the boat’s trim will be noticeably altered. Worse yet, the boat’s pitching moment is likely to be amplified, making her less comfortable in a seaway. To further confuse matters, as the fuel or water in the tank is used up, trim and balance continually change.

Although it may be slightly inconvenient, the space under the V-berths is best given over to dry storage such as bedding and clothing. Although drawers waste space, they are more convenient to use, and eliminate the need to lift the cushions to gain access to the space.

A forward cabin should have ventilation. This is most likely to consist of a hatch over the head of the berth in the deck or top of the cabin trunk. The aluminum-framed translucent hatch is another great modern invention. In all but the smallest boat, there should be a light at the head of each side of the V-berth. (Just remember that with transparent hatches, strollers on the dock can usually stare into your forward cabin if the lights are on at night.)

To improve privacy, some means of shutting off the forward cabin is desirable. In a small boat whose forward cabin merely consists of a V-berth, this could be something as simple as a curtain or a sliding panel. In a larger boat with real standing space in the forward cabin, a sliding or folding doors preferable. Louvers in the door will aid ventilation but at the sacrifice of some privacy. Again, compromise is a way of life in boats.

Storage can be augmented by shelves under the deck head. These are most useful if they have high fiddles and are subdivided into smaller sections. If you mount too many things on the bulkhead at the head of the berth, there may be no comfortable place to lean while reading.

Few things are less attractive than the bare inside of a fiberglass hull. We have never gotten over the insecure feeling of seeing the sun stream through translucent topsides. For both aesthetics and function, some form of hull ceiling is desirable. More and more boats are sealing the interior of the hull with thin wood strips, the rebirth of a practice that makes the inside of a wooden yacht so enjoyable.

Teak is not the wood to use here, being heavy, dark and expensive. A wonderful alternative is eastern white cedar or western red cedar, both of which are highly aromatic and beautiful when varnished. We have not found anyone who enjoys the smell of fiberglass so much that a little aromatic cedar cannot warm his soul. Vinyl and carpet liners, while functional, make the boat look like an airplane or a house trailer. They may also be subject to mildew if they are not kept dry and clean.

Some form of hull liner will also help reduce the condensation that can make the interior of an uncored hull uncomfortable. Ceiling may not be necessary on a foam- or balsa-cored hull, but for pure aesthetics, few things dress up a boat so quickly. Since forward cabins are inevitably cave like, anything you do to brighten the decor is likely to be an improvement.

The Head. Except in very small Cruising in Comfort on a Sailboatcruising boats where the head may be located under the V-berths forward, the head is usually located in a compartment immediately aft of the forward cabin. The degree of privacy attainable in the head is largely a function of the size of the boat.

In boats under 30 feet, it is usually desirable to have a head arrangement that can span the full width of the boat. While a cramped head compartment is hardly the end of the world, if it must be used for dressing and showering, a little extra elbow room is nice.

The primary fixture of any head is the water closet, the basic design of which has not changed in this century. Most stock boats come equipped with the cheapest toilets available, most frequently the Wilcox-Crittenden Head-Mate. While these toilets are readily serviceable, their small cylinders make them harder to pump and more likely to clog than a more expensive unit. Boat builders use cheap toilets simply to keep prices down. A Head-Mate or comparable Jabsco or Raritan toilet sells for about $ 125, while a top of the line head such as the Wilcox-Crittenden Skipper costs three or four times as much.

To clear the air once and for all, unless a boat operates in an enclosed body of fresh water, we do not believe in holding tanks. The well-intentioned but poorly thought-out MSD laws are no more than a Band-Aid on the gaping wound of water pollution. In tidal saltwater areas, we have absolutely no guilt about pumping the toilet directly over the side. We seriously doubt if as many as 20 percent of the boats in existence conscientiously abide by the head regulations.

Manufacturers, of course, must comply, so new boats are invariably equipped with holding tanks. Do yourself a favor; install a diverter valve and forget you even have a holding tank.

The head compartment must have grab rails which give you something to hold onto when using the head underway. There should also be ventilation in the form of opening ports for use in fair weather, and one or two large cowl vents for bad weather. An unventilated head compartment will be a misery forever.

While a sink may not be necessary in the head, it is a useful addition if there is room. Small, round-bottom sinks are less than useless; water runs out of them if the boat is heeled more than a few degrees, and it is impossible to wash your face over one without soaking the counter. The sink need not be as deep as the galley sink, but make sure it is more than a toy.

If the head has a shower, it should drain into a sump, not into the bilge. This is one of the most common faults in production sailboats. Hair, soap, and scum will clog the bilge pump and render the bilges as pleasant as a sewer. The only thing that belongs in the bilge is bilge water – not shower water, not icebox water, and certainly not engine oil.

The head should contain lockers for toiletries. Small cubbyholes or drawers which can be labelled with each crew member’s name are ideal. Linen or hanging lockers, depending on the size of the boat, may be desirable.