This chapter introduces the basic concepts involved in the financing of LNG export projects and associated infrastructure. Although some projects, such as Nigeria LNG (1 and 2), and Gorgon in Australia, were financed directly by their sponsors, the more common method of raising capital has been through a staged project finance structure.

- Project Finance Structure

- The Financing Process

- Available Funding Sources

- International commercial banks

- Domestic banks

- Islamic banks

- Export credit agencies

- Development Banks

- The World Bank Group negative pledge clause

- Sponsor co-loans

- Other providers, debt, and equity

- Impact of Market Shifts on Project Finance

This article, therefore, focuses on finance structures followed by a discussion of the finance process, various funding sources, and impact of the current state of the global LNG markets.

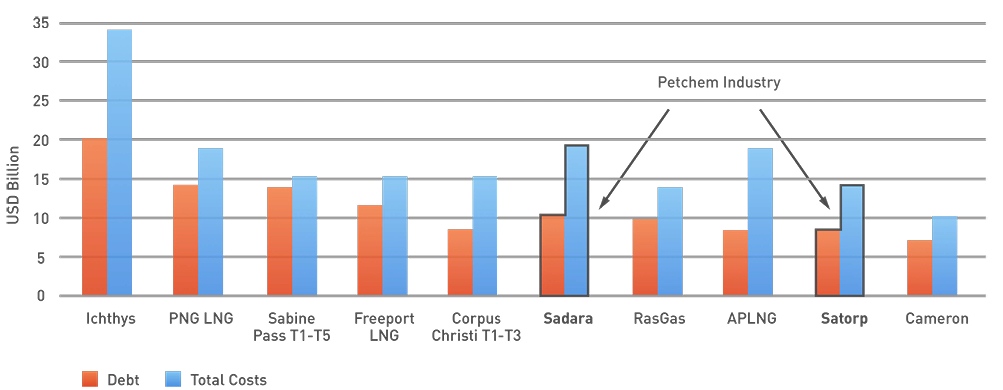

The first project financing transaction in the LNG sector was for Australia’s Northwest Shelf in 1980. Since then its use has become routine and project finance has been used in many different types of large projects. Ranked by debt, LNG projects occupy eight of the top ten slots for all project financing completed globally between 2005 and 2015, as shown in the chart below:

In project finance, all of the development cost, assets, permits and contract rights of the project company are used to support the finance structure. The credit of the project company’s counterparties is used rather than the credit of the project sponsors that create and own the project company. The project lenders rely on the cash generated by the project (e. g. LNG sales contract duration/revenue forecast) to pay back the debt and not on the balance sheets of the project sponsors. For this reason, it is also referred to as “off balance sheet financing” and “limited recourse financing“.

Given the magnitude of the capital required for LNG projects, most are implemented by more than one project sponsor and require multiple funding sources. Government and corporate sponsors are often unable or unwilling to provide sufficient sovereign or corporate credit to finance LNG projects. Project finance structures provide reasonable protection for all parties and contractually protect against the contingent liabilities of partnership.

To implement a project finance transaction, project sponsors establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that allows banks, export credit agencies (ECAs) and other financiers to lend money directly to the project company or specific assets (e. g., LNG Train 3) instead of to the individual project sponsors. Currently, all liquefaction projects require long-term “take-or-pay” LNG sales or tolling contracts to allow them to raise funding through project and equipment finance structures. Because the assets, permits and contract rights of the project company are the sole sources of debt service, international project finance involves careful analysis of the various risks associated with the project. New insurance products such as first loss policies or environmental protection insurance are bringing new sources of funding such as pension funds. The agreements to which the project company is a party must be precisely drafted in order to ensure that these risks are properly identified and allocated among the project company’s counterparties.

Project Finance Structure

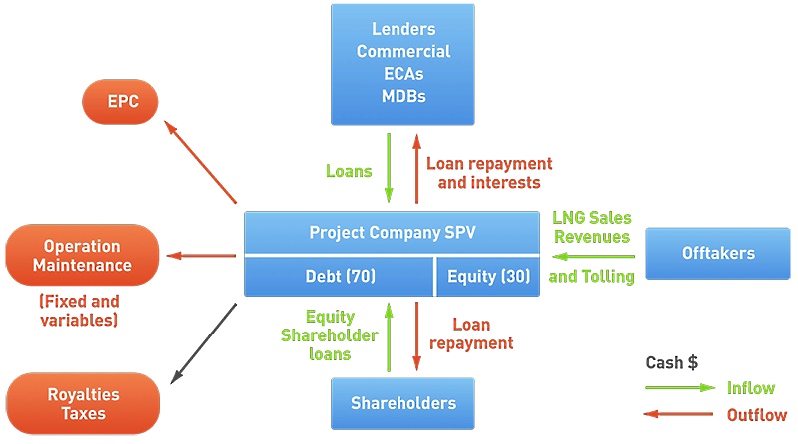

The following diagram depicts the relationships between the project sponsors and the financiers and the cash flows:

Debt to equity ratio

As a result of the large cost of LNG projects, they are typically highly leveraged. A target of 70:30 debt to equity ratio is the norm. The project partners will provide the equity and sometimes bring in other financiers to provide equity. The debt is typically provided by banks and other lenders. Consequently, a large proportion of project sponsors look at generating large amounts of debt, but in project finance, this is located off balance sheet. So using project finance will allow sponsors to maintain their corporate debt/equity ratio.

Limited recourse to project sponsors

LNG project finance is essentially based on “limited recourse” finance, which means that the loan is given to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) instead of the project sponsors. As a result, lenders rather than sponsors assume the lion’s share of risk associated with the project. However, during the development phase of the project, the sponsors (or shareholders) usually provide financial cover to the lenders until startup and completion tests are met. This is provided via a completion guarantee.

Read also: Liquefied Natural Gas Carrier Market Insights

Equally, shareholders would try to pass on some of the risks to the engineering procurement and construction (EPC) contractors. EPC contractors provide the shareholders with security via a lump sum turnkey contract, which means that the contractors have to shoulder the risk if there are problems with plant performance during startup leading to delays. When production starts and targets are met with proper completion tests, financial recourse to sponsors is canceled. This differs greatly from traditional balance sheet based loans.

Public-Private Partnerships in higher-risk countries

LNG projects always require government support, this is for political reasons, risk mitigation, regulatory framework matters, interactions with communities, and contract stability and enforcement. Often the government (national or regional) is a shareholder in the project. The government may not be in a position to access finance to contribute equity or other development costs, and equally, investors may not be willing to cover the government’s development costs. The role of project finance is to ring-fence the project and enable the project company to borrow money under its own name, accessing terms more favorable than the government would obtain, thereby reducing the impact of the low credit rating of the host country.

Special Purpose Vehicle

In order to successfully implement a project finance transaction, project sponsors typically establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that allows banks, export credit agencies (ECAs) and other entities to lend money directly to the project company instead of to the individual project sponsors. By comparison, if corporate finance was used, each sponsor would be required to finance its portion of the project, using a combination of capital on hand and individual loans, which would limit the amount of debt that can be raised by entities with lower credit ratings.

Offshore ventures

In some instances, the project developers also create an offshore account that will receive cash inflows from lenders, equity from shareholders, and LNG sales revenues. Debt will be serviced from this offshore account. While this does not mean that the SPV is exempt from tax in the host country – which is usually regulated by law and negotiated contractually – this serves to mitigate country exposure both political and economic, as well as facilitating cash flows that could be compromised by host country banking system performance. Offshore ventures are regulated and negotiated contractually to enforce international law and US Foreign Corrupt Practices act agreements and equivalent.

Loan tenor/payback period

Debt is provided by a syndicate of lenders (such as commercial banks, pension funds, investors in the public bond market, export credit agencies and government-backed lending institutions), who differ in terms of the amounts they lend, lending conditions as well as the ranking in the order of repayment. A typical loan tenor (meaning the time left for loan repayment) commercial banks would accept for LNG projects would be 10 years for high-risk countries. The tenor terms are based on a debt service coverage ratio which can be determined using financial models. The loans are priced at a margin applied above the base rate, which is often the London interbank offered rate.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

The loan pricing or margin will depend on an assessment of a project’s risk and on the cost of funding. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), regional development banks, and European Investment Bank (EIB), have specific loan products that can offer more favorable tenor terms though they usually constitute a small proportion of the total debt amount. Because of the time necessary to recover the capital investment costs – typically around 7 years – longer tenor terms are favored by project developers.

Long-term sales-and-purchase agreements

Firm long-term agreements among LNG exporters and importers are generally required for up to 80 % of the project’s capacity. They typically cover contract periods of about 15 to 25 years, thus exceeding the anticipated loan payback period – normally in the range of 7 to 15 years. However, shorter term contracts are becoming more prevalent (see section below).

Inputs from ECAs and MDBs

The lengthy and thorough due diligence process involved in a project finance transaction, together with the economic development implications and the importance of the political environment, is well suited to ECA and MDB involvement. Since the mid-1990s, MDBs and ECAs have played a growing role in structuring LNG projects. They can finance them through direct loans, political risk coverage or loan guarantees (see the section on “Available Funding Sources” below).

Risk mitigation

A key advantage of project finance is that it allows developers to mitigate the risks associated with politically or economically unstable environments. Such projects face a risk of expropriation, political turmoil, labor strikes, land rights issues, and other unforeseen disruptions.

Debt recovery and default rates

Experience has proven that the use of project finance for liquefaction projects has resulted in remarkably low default levels.

Project financing can have its drawbacks. Because banks lend to a project company, with limited recourse to the actual project sponsors, the due diligence requirements take time and money. While these drawbacks are significant, liquefaction project sponsors have historically found project finance advantages outweigh its drawbacks. But they tend to use it only when it allows them to finance projects with weaker credit partners or at the behest of national oil companies.

The Financing Process

The time taken to arrange project finance will depend on the development processes, project cost, the risks associated with the project and the host country, and number and type of financiers needed. Also, external market conditions such as commodity prices and the amount of liquidity in financial markets and foreign currency fluctuations will have an impact on timing. The size, complexity, and scope of major LNG projects require a wide range of advisors both on the side of the investors and the host government, together with the commitment of substantial resources throughout the financing process by both the government of the host country and the project sponsors.

This process, from initial discussions to finalizing the financing (financial close), can take as long as two years. In countries with little experience in the sector, or without appropriate policy and regulatory frameworks, the financing process can take much longer. Companies typically appoint a financial advisor to help structure the deal. The financial advisor will be appointed at the same time, usually, as the legal and technical advisors. The financial advisor is often selected from a group of advisors known by the commercial bank community. In addition, development banks, such as the IFC and regional development banks, can also be appointed at an early stage to provide advice on financial structuring.

Reserves will be delineated, the project company will be formed and will obtain its permits and licenses, and the project agreements will be structured, negotiated and executed by the stakeholders, including the government. Each of these tasks will require commercial, technical and legal resources. The financing discussions will start concurrently with FEED studies and tenders for EPC contractors. Often companies and their advisors will hold initial talks with the banks – known as “soundings” – in order to gauge their interest in participating in the project financing and to pinpoint any impediments to fund-raising.

Early in the process, the financial advisor will consider equity as a source of finance. Assessing the amount of equity available for the project will determine the “gearing” ratio and the amount of debt that the project needs to raise. The project will reach out to potential interested shareholders, typically parties with a specific interest in the project, such as off-takers, tolling counterparties, or EPC contractors and/or entities that have a large amount of liquidity available and looking for long-term stable returns with limited risks. These entities could include pension funds.

On the debt side, the financial advisor, with input from the project sponsors and their advisors, will produce an information memorandum and financing request for proposal (RFP) which will be sent to banks. This will contain all the pertinent details that are needed by potential financiers to assess the project. It will include details on the LNG offtake or tolling contracts, as encompassed in the sales and purchase agreements or tolling agreements.

The information memorandum will include details on project construction, EPC contract, and timeline, plans for shipping, and operations and maintenance details. Technologies used will also be detailed. Banks do not have a strong appetite for exposure to new technology risk, so adequate protections, provided by sponsors, need to be in place if anything untried is introduced. This is the case for early floating liquefaction units, but lenders’ concerns can be dealt with by use of a sponsor completion guarantee which is only released once the unit is operating according to parameters specified in the documentation.

The information memorandum will also include Health, Environment and Safety Management for LNG Transportenvironmental protection and remediation. When assessing the environmental and social impact of projects, many financial institutions will use a risk management framework called the Equator Principles. As of the end of 2016, 85 financial institutions across 35 countries had adopted them. They include some of the big commercial banks which can find themselves a target of NGOs if they do not meet social and environmental standards when funding projects.

The financiers will be provided with commercial and financial models in tandem with the information memorandum. They will use various ratios to assess the project’s risk, one of the most important being debt service coverage ratio (DSCR). The company and its advisors may provide indicative pricing in the model for the debt, although this will be decided based on market considerations.

It will interesting: Custody Transfer Measurement System (CTMS) on Liquefied Gas Carriers

Banks will assess the risk of lending to a project and if they decide to go ahead, they will approach their credit committees to get approval. Banks have their own internal rating systems for countries and this will be applied, but a decision to lend to the project is based on a consideration of all of the project’s characteristics. They will determine whether the project structure and the project financing are sufficiently robust. They will take a view on the ability of the EPC contractors and project sponsors to implement the project.

Of special significance to the lenders are the offtake or tolling agreements. These need to be of sufficient duration to allow the debt to be serviced across long repayment horizons. They also need to be with creditworthy counterparties. Banks do not want exposure to market risk. Decisions are made by banks whether to fund projects on a case-by-case basis as no two projects are alike.

A critical element of a lender’s assessment of the project will include thorough legal due diligence to determine whether there is any fatal problem with the project that could jeopardize the project company’s ability to make debt service payments. The scope of legal due diligence should be tailored to the characteristics of each project, but typically will include:

- An analysis of the laws of the host country.

- A contractual alignment review to ensure that the major project agreements have consistent provisions and do not contain any unintended contractual disconnects.

- A review of the project company’s permits and licenses to ensure that they are adequate to construct, own and operate the liquefaction project and were obtained in compliance with all applicable laws.

- An analysis of the project company’s real and personal property rights.

The finance documents, including the mortgage and security documents, will also be carefully reviewed and commented upon by the project lenders and their respective counsel.

Banks will reach a consensus price for the project, expressed in basis points over the London interbank offered rate. Banks also receive other fees for participation, such as up-front fees and commitment fees. When a sufficient number of banks have received credit approval, the financing agreement or term sheet can be signed and the project can move to financial close and the drawdown of funds can begin.

The banks can provide financing as part of a club deal, or there can be a syndication process where a few banks agree to provide funding to the project. They then syndicate this to a wider group of banks. Debt is paid back to the lenders from the project earnings. The loans may be refinanced or repriced to take account of changing market conditions if agreed by the project company and lenders.

Available Funding Sources

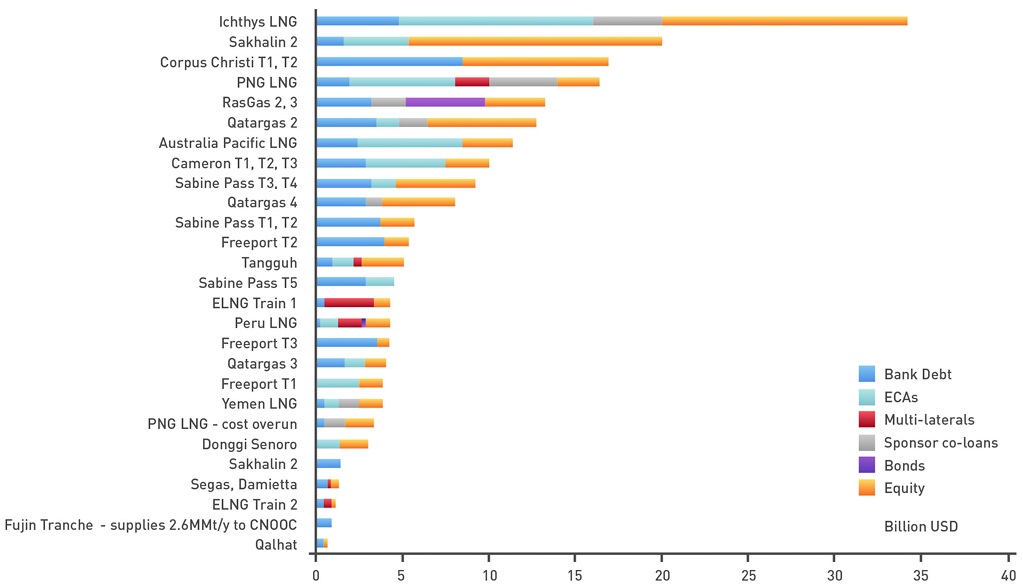

LNG projects raise funding from a variety of private and public funding sources as illustrated in the following diagram:

International commercial banks

Commercial banks have historically been the main providers of funding to liquefaction projects. As projects grew in size due to the need for economies of scale, and thus became more expensive to construct, banks were unable to provide all of the debt required. As a result, more funding sources were tapped. The need for access to other types of funding also became more urgent in the immediate aftermath of the 2008-09 global financial crisis as banks became more constrained due to their increasing internal funding costs. Initially, the problem was the erosion of confidence in banking counterparties – banks stopped lending to each other. Thereafter, constraints arose as a result of tightening legislation enacted to prevent a repetition of the events that triggered the crisis.

The implementation of stricter guidelines has continued. For example, under so-called Basel III guidelines, which are to come into full force by the end of the first quarter of 2019, banks are directed to apply more capital to long-term loans. Project finance loans fall into this category because their tenor typically extends out beyond the Basel III threshold. This is much longer than corporate loans. And it appears that successive revisions of the guidelines, which are published by the Bank of International Settlements, could require the application of more capital against long-tenored loans and loans that are assessed as being of higher risk. A wide range of international commercial banks will invest in LNG project finance transactions, although globally dominant players tend to come from Europe and Asia. But in LNG project finance it is not uncommon to have over 20 banks from several countries lending to a project. Increasingly, banks are selective and will make a decision on whether to provide loans based on whether they see the borrower as a key client who could possibly provide them with further business in the future or ancillary business related to the transaction, such as foreign exchange and interest rate hedging.

International commercial banks will typically provide loans to liquefaction projects in dollars because LNG cargoes are priced in dollars. This minimizes exposure of both lenders and the project entity to foreign exchange risk.

A bank will determine the risk of a project based on its own internally determined country classifications, but it will also take into account many other characteristics of that project. The project will possibly have a lower risk than the country in which it sits if it is being implemented by creditworthy sponsors, has brought in an experienced engineering, procurement and construction contractor, and, crucially, if it has long term offtake or tolling contractors with creditworthy counterparties.

Domestic banks

Domestic banks can be a lot smaller than the international commercial banks which appear frequently on global LNG project finance transactions. They may also have limited access to dollars. However, in some project finance transactions, a separate tranche of loans can be provided in the local currency to allow local lenders to supply funding to the project.

Islamic banks

These banks are governed by Shari’a law and can also provide funding to LNG projects. The Islamic bank funding would be in a separate tranche, which would have its own Shari’a compliant structure. These funds would still sit within the debt side of the project financing structure. Islamic banks are mostly, but not exclusively, tapped for funding in countries where common law is Shari’a-based.

Export credit agencies

Export credit agencies (ECAs) became important providers of funding as liquefaction projects grew in size and cost and more sources of funding were required. But after the global financial crisis (see “International commercial banks” above) they took on an even greater role. ECAs are bilateral lenders and their primary role is to support exports from their host countries. Most of the ECAs supporting projects are from OECD countries.

They will be able to participate in a project financing if the project includes content from their host countries. Local content can include equipment, services, expertise and equity participation. They broadly follow similar rules in assessing whether to provide funding and at what level of pricing.

The minimum pricing level for all ECAs is determined by looking at commercial interest reference rates and country risk classifications, which are published by the OECD. However, ECAs will also apply discretion when looking at projects. Each project will be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

So if the country risk classification is of a certain level, but the project features strong sponsors, engineering, procurement and construction contractors, and most importantly, long-term offtake or tolling by creditworthy companies, the project will have a higher rating than the country in which it sits.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

ECAs can support a project in a number of ways. They can provide direct loans, but they can also provide commercial and political risk cover (sometimes up to 100 %) for loans to which the banks supply the underlying funding. For loans that are covered by ECAs, the risk to banks then becomes that of the ECA’s host country rather than the risk of the country in which the project is located. This has important ramifications for the pricing of the loan since it would be priced based on the ECA’s own country credit risk. It should be noted that most ECAs that participate on LNG projects are from OECD countries with high credit ratings. Banks will have to apply less capital, under banking guidelines, to higher rated loans and so ECA cover can help attract more banks to the deal.

ECAs have provided a considerable amount of funding to LNG projects. The Export-Import Bank of the US, for example, provided almost $10 billion in direct loans to seven Project Management of the Large-Scale Liquefied Natural Gas Facilitiesliquefaction projects between 2003 and 2015. These comprise Nigeria LNG, Qatargas II and Qatargas III, Peru LNG, Papua New Guinea LNG, and Australia’s Australia Pacific LNG and Queensland Curtis LNG. Most of this funding was provided to projects that were using project finance structures, with the exception of QC LNG.

The Japanese Bank for International Cooperation has been a big supporter of LNG projects. Japan is natural resource poor and as it has sought access to LNG, its domestic utilities have participated as offtakers or tolling counterparties or as EPC contractors on projects. For example, JBIC provided a direct loan of $2,5 billion to the Cameroon LNG project and sister agency, Nippon Export and Investment Insurance also provided $1,57 billion of cover to the project. China’s ECA, Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim) is increasingly providing funds and cover to LNG projects.

China Exim and China Development Bank agreed to provide direct loans of €9,3 billion ($10,54 billion) and RMB 9,8 billion ($1,51 billion) in April 2016 to Russia’s Arctic 16,5 MMt/y Yamal LNG project. As a result of sanctions implemented against Russia by the EU and US, this is one of the few LNG project financing transactions to receive loans in currencies other than dollars.

Given the large amounts of both cover and funding that can be provided by ECAs, the desire to unlock that support can drive the selection of EPC contractors.

Development Banks

Some development banks come in early to structure projects – such as the IFC, regional development banks or the EIB. Their roles can include equity participation, due diligence, benchmarking against international best practices (using thorough social and environmental safeguards), lending and syndication, as well as offering risk coverage guarantees. In addition, because development banks usually have long-standing relationships with host governments, which may include access to lawmakers and government officials, their participation in the project can provide added confidence to lenders as a risk mitigation factor.

The World Bank Group negative pledge clause

When providing loans for infrastructure development projects, instead of taking a lien over the state’s assets, the World Bank protects its interests via a broadly-worded negative pledge clause. This clause ensures that any lien created on any public assets as security for external debt that results in a priority for a third-party creditor will also secure all amounts payable by the borrowing state. In short, should such a lien be granted, the World Bank shares in the amounts paid out to the third-party creditor, thus preventing the creditor from enjoying senior creditor status and undermining the value of any later granted lien. As a consequence, the clause undermines the state’s ability to engage with other creditors and can end up preventing the state from attracting commercial investment for project financing. This needs to be carefully examined when considering raising debt from the World Bank Group, given the cons might outweigh the pros in assembling the overall debt package for the project.

Sponsor co-loans

These can be tapped for large projects where the funding needs are considerable. Sponsors, in this case, act as debt providers and receive a margin payment for their loans in the same manner as banks. They typically rank pari passu, on equal footing, with the other debt providers.

Other providers, debt, and equity

Projects can also raise financing via other means, although these are less common. They can issue bonds, which can sit within the debt side of the project finance structure and rank on an equal footing with other lenders in terms of payback. However, bond investors do not relish construction risk exposure, so bonds are often offered post-construction and are mostly used to refinance bank debt. To issue project bonds, project sponsors will employ a bank or group of banks as book runners. They will promote the project via a “roadshow” to countries where they expect investor appetite for the project will be strong.

Private equity companies and pension funds are also stepping up participation on LNG projects. Project sponsors can also raise equity for the project through share offers, although thus far this activity in LNG is prevalent mostly in the US.

Impact of Market Shifts on Project Finance

The global LNG industry is undergoing a transformation as technological advances are uncovering massive new gas reserves. LNG infrastructure is changing rapidly with the advent of new technologies, natural gas prices are becoming increasingly decoupled from oil prices, and US LNG exports are introducing new flexibility into global LNG marketing and trading. The number and type of LNG market participants have increased dramatically as lower prices make imports more affordable, with floating storage and LNG Plant and Regasification Terminal Operationsregasification units also facilitating the opening of new markets. Short term and spot LNG transactions are making up a greater portion of global LNG trade. The current LNG supply imbalance and low oil price environment have also put downward pressure on global LNG prices.

These changes are impacting LNG project finance. Liquefaction projects are less likely to be structured as point-to-point integrated projects with dedicated shipping where the credit of an investment-grade utility buyer provides the financial underpinning for the entire LNG value chain through a long-term take-or-pay LNG SPA indexed to oil prices. LNG project finance in the wake of this market shift will require innovative structuring and project agreements. Tolling structures with creditworthy tolling customers will likely continue to be used to allocate LNG market risks away from LNG project company borrowers. With respect to integrated and merchant structures, although long-term LNG SPAs will likely continue to be required in spite of the growth of short-term and spot LNG trade and price reopener provisions, international oil companies and LNG aggregators and trading companies are developing shipping and portfolio capabilities that may provide solutions to project lenders.

Read also: Top LNG Carrier Builders in Marine Industry

New countries and companies are seeking to develop new LNG supply projects; construct large numbers of LNG ships; and develop new LNG regasification terminals. Patterns of ownership and project structures are changing and the boundaries of risk allocation between buyers and sellers are shifting. This has a direct impact on the ability to finance LNG projects, at a time when the availability of third-party finance could become squeezed with the implementation of Basel III guidelines which determine how much capital banks must set aside for long-term loans. Moreover, these developments are taking place in an environment of reduced gas prices combined with uncertain price projection scenarios.

Limitations in the availability of third-party debt could lead to greater use of shareholder funds, which in itself will limit the number of companies that can invest in the LNG sector. Projects need competitive lending as a means of mitigating debt costs and improving overall economics. Reduced availability of project finance debt may undermine some LNG project developments. It will also encourage the use of alternative financing structures and expand the role of export credit agencies (ECAs), which are already being used by energy consuming governments as a way of seeking a competitive advantage in sourcing LNG.

On the other hand, there are positive signs for the development of LNG and natural gas markets. First, there are an increasing number of LNG importing countries, which provide more opportunities for offtake contracts as well as a diversification of the contracts portfolio to cater for an array of economic and political risks. Second, the reduced LNG price has enabled more customers to access the commodity, which provides for an increase in the overall market size and customer base. Third, new technologies such as floating storage regasification units and smaller scale LNG transport mechanisms allow for a more flexible market that can serve a wider array of customers. Smaller scale LNG also provides a platform for developing the natural gas market in emerging economies.

Natural gas has been recognized as an important part of the clean energy mix, with demonstrated success in lowering emissions. Trends indicate that the LNG market is maturing and will provide more diverse options for both producing and procuring LNG that could serve a variety of institutional and private customers.