Yacht Performance is a crucial factor for any sailor looking to maximize their experience on the water. It encompasses various elements such as hull speed, stability, and maneuverability, all of which contribute to how a yacht handles in different conditions. A well-designed yacht should perform efficiently, whether sailing to windward or cruising with ease. Understanding the displacement and stiffness of the yacht can also provide insights into its overall seaworthiness.

Safety features are paramount, ensuring that the yacht can withstand the challenges of the sea. Ultimately, a thorough understanding of yacht performance allows sailors to make informed decisions, enhancing their enjoyment and safety while sailing.

The yacht itself

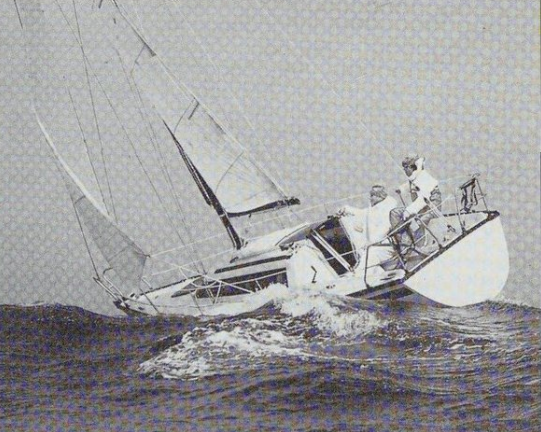

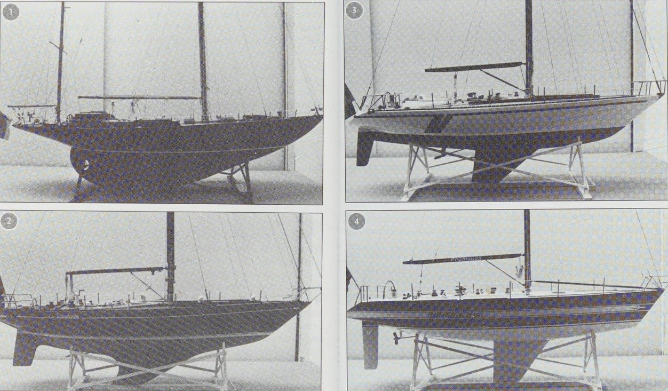

If there is one main criticism of modern glassfibre yachts, it is that their appearance tends to be starkly uniform. However, it can equally be argued that the boat buying public has got exactly what it demanded: an emphasis on domestic niceties. These include double berths, galleys with all the trimmings of double sink, fridge and cooker and, since the design of yacht interiors mimics housing trends, not one WC but two (one en suite!). The boat is also required to look good. These are onerous demands to place upon a yacht that will be expected to sail and motor efficiently, manoeuvre predictably, and be rewarding to handle. In addition, the overloaded beast must not only be selfrighting, but also unsinkable into the bargain. It is a lot to ask, and unfortunately most of these requirements are mutually incompatible.

The lack of individuality of hull, superstructure and rig is further reinforced by the fact that many craft share the same colour scheme: white with a mid-blue trim band. This being the case, it is not difficult to understand why potential buyers are persuaded that in fact the only real difference between the boats is the overall length of the hull. This is a fallacy – though in all fairness, all fibreglass production boats, by the very nature of construction method, do differ from one another less obvious than was the case when each boat was built on a one-off basis (usually to order – and in timber).

Because of the superficial resemblance between yachts, it has become especially important to make direct comparisons if specific qualities are to be recognized. The best (and most pleasant) way of establishing behavioral differences in designs is simply to sail several different examples in the size and price range you have in mind. However, in order to gain a true picture, each would have to be sailed in a wide range of wind strengths and sea states; this would rarely be feasible without the expense of a week’s charter – and in any case, comparable boats may be lying hundreds of miles apart from one another.

However, as this book shows, there is another solution: no matter where the boats in question are based, it is possible to work out a theoretical comparison by calculations that use certain measurements of the boats. There will be some limitations – and there may also be discrepancies between the designer’s measurements and actual measurements – but the theory works well in practice and could save you the wasted time, effort and expense of travelling around to inspect unsuitable yachts.

The Facts

In the case of a Cruising in Comfort on a Sailboatcruising yacht, the requirements must be that it performs well on all points of sailing, remains controllable in all circumstances, and offers comfortable accommodation that is tenable offshore as well as in port. The vessel must be strongly constructed and practically equipped to cope with heavy weather. Of course, size has to be taken into account, and clearly a boat of 6 metres will not offer the comforts to be expected on a vessel twice that length; the differences in accommodation, deck and cockpit space imposed by size, though, are not too hard to assess by eye, whereas the sailing/handling qualities probably will be. Even the experienced may benefit from studying the comparison figures resulting from the use of calculations and coefficients, With practice, there comes a better awareness of hull shapes and their associated characteristics.

When looking at a yacht, the first things likely to come to your attention are the overall length (and, possibly, the displacement), the keel and rudder, and the shape of the stem and stern. Also, you may get a general impression of the section and profile of the under body. Don’t be too dismissive at this stage; it is said that all cruising yachts are a compromise and appearances may be deceptive – that «bathtub» you are looking at might turn in surprising speeds in certain conditions and be beautifully balanced as well.

Of course, each boat must be looked at in context – it is pointless to sneer at a motor sailer for possessing every conceivable on board luxury if your own inclination is towards sheer, brutal performance at any price. Neither, by the same token, should you be unduly critical of a dedicated IOR racer simply because the crew have to rough it in pipe cots!

Regrettably, the way in which boats are actually sold can be misleading: craft with an unrealistic number of berths and domestic utilities crammed in are portrayed as being fast enough to race – if not at the top level, then at least with a fair degree of success – and, baldly, this concept of cruiser/racer does not work well with today’s designs (racer/cruiser is, by definition, a combination with even less going for it).

Sailing Performance

Unfortunately, a yachts performance is usually judged solely by the speed and the degree of ease with which other yachts can be out sailed. Top speeds of conventional ballasted yachts can hardly be improved upon because the speed is determined by the length of the waterline. As soon as it achieves its hull speed, every displacement yacht reaches a kind of barrier that cannot be broken, even if the sail area is increased.

This barrier can possibly be delayed by applying suitable constructive measures. A yacht’s drive through the water is reduced because of resistances that every designer tries to keep to a minimum. His ability to do this is, however, limited because of clients’ demands for certain measures and build features. (You can observe how well the designer has solved this task by observing the pull of the anchor line of a yacht anchored in a current;this is where friction and form resistance are unified into an overall hydrodynamic resistance that has to be overcome by the sail force.) I here sistance due to friction on the underwater parts of a boat (skin friction) and the resistance due to the yacht’s hull shape (form resistance) change with the speed of the water.

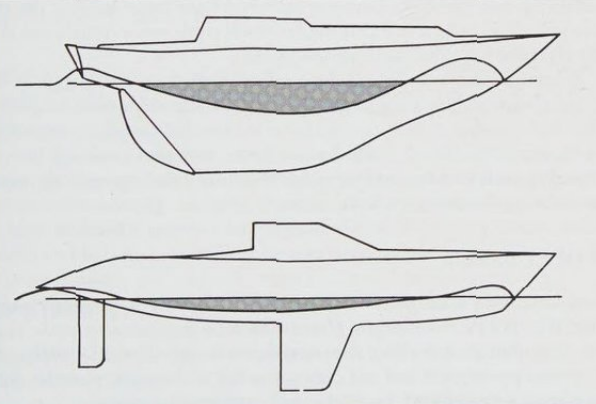

A slow sailing vessel may initially have to overcome more skin friction, but when it sails faster, then form resistance increases. The resistance due to friction also increases with the size of area that is submerged in the water – the wetted surface. A boat designer can influence the wetted surface by reducing the underwater hull, shortening the keel, and designing a sharper midship section. Another speed-reducing factor is the roughness of the hull. This is something that the boatyard will take care of initially, but it is, of course, the owner’s responsibility to keep the bottom of his yacht clean in the future.

Displacement

The wave resistance of a displacement yacht also limits speed. This resistance eventually increases to such an extent that even increased drive power will only produce waves. The production of waves follows a physical rule whereby no energy is lost; it is simply transformed into a different form. When the particles of water reach the yacht, irrespective of whether the water is moving or the boat, they possess a certain velocity. The water particles are stopped at the hull; this decreases their movement or kinetic energy. Because the overall energy remains, comprising kinetic and potential energy (lifting energy), the potential energy has to increase, thus the water rises at the bow.

The kinetic energy increases again behind the stern post, which increases the speed of the water particles – thus the water falls (away from sections where the hull is broadest). A wave trough develops, which becomes larger the higher the speed and the bigger the submerged volume. The trough stretches with increased speed and the wave moves further aft. A large displacement midships and a deep midship section that is U– or even V-shaped produce a deeper wave trough than light displacement with flat sections. Slim, well-drawn-out counters, as were once common in conventional long-keeled boats, produce the mount of the wave precisely at the end of their waterline.

In the search for speed, a yacht is affected by form resistance; this is largely determined by the length of the hull, the fineness (or otherwise) of the ends and by the midship section. Together these combine to produce wave resistance, and this the designer can modify by alterations in the section and lengthening and fining the waterlines of the entry and run aft.

As well as these resistances, there is also the induced resistance of the hull, and this particular speed impediment is brought about by such factors as turbulence at the propeller, shaft bracket and rudder. A poorly designed transom is another common cause (or a transom that is too deeply immersed because there is excess weight carried aft). Steep heeling angles increase resistance markedly – especially in the case of those yachts with broad-beamed under bodies, and these should always be sailed upright. Wind age caused by high free board, bulky superstructures and heavy masts with rigging to match – also, external halyards – has been claimed to add as much as 10 percent to the overall adverse resistances.

This can be seen in some wooden boats. Yachts with overhanging and simultaneously flatter stern lines sometimes produce the wave crest behind the transom. If a yacht is sailing at or near ultimate speed, the bow and stern both lie on a wave crest. At this point a displacement yacht has reached the hull speed. In theory, it cannot get any faster because the aft wave will move so far astern that the bows will crash into a trough and the boat therefore has to sail more or less «uphill».

If the Basic Hull, Keel, and Rudder Shapeshull shape is cleverly designed, it might be possible slightly to expand the so-called «wave-generating length», so that a light boat with only a few wave-producing lines can sail faster than its hull length in the water would actually permit. A shallow wave system requires less energy than a deeper one with the same wave length – therefore a yacht generating fewer waves also loses less energy for her drive.

Hull Speed

Every wave has a speed that strictly depends on its length. It cannot move faster than 2,43 √ wave length. Consequently, a displacement yacht that cannot produce a longer wave than its effective waterline permits is trapped in its own wave system and can only sail as fast as the wave; thus the ultimate speed is 2,43 √ LWL (speed in knots and length in metres).

Yachts with modern stern profiles may exceed this speed up to a value of 2,72 if the conditions are favorable; light displacement yachts might even reach speeds of up to 3,62 √ LWL. To be precise, it depends on the effective wave-generating waterline, which can theoretically already be extended either through the boat heeling or by shifting the ballast. This produces the higher values.

Only racing machines, dinghies and light centreboarders can achieve true planing conditions. The speed of a Flying Dutchman (FD, 20 ft International dinghy class), for example, has been measured at 14,5 knots, which results in a speed-to-length ratio of 6,34. A cruising yacht with full tanks and holiday gear will not be able to exceed the value of 2,43.

Stability

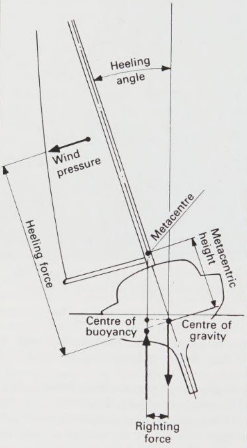

A sailing yacht will only attain ultimate speed if it is in a position to carry the necessary sail area for forward drive. The stability factor plays a vital role in the driving performance. The stability of a yacht is characterised by the ability to return upright from a heeled position. Sufficient stability is also, therefore, a safety factor.

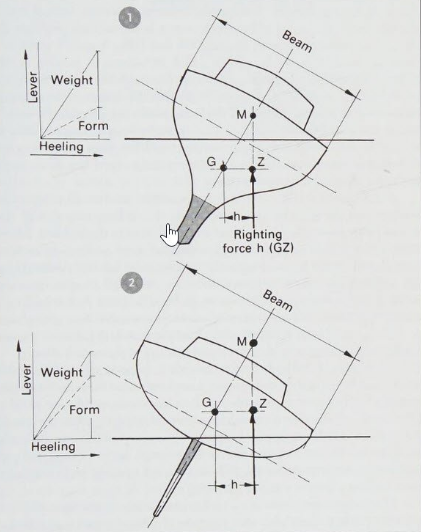

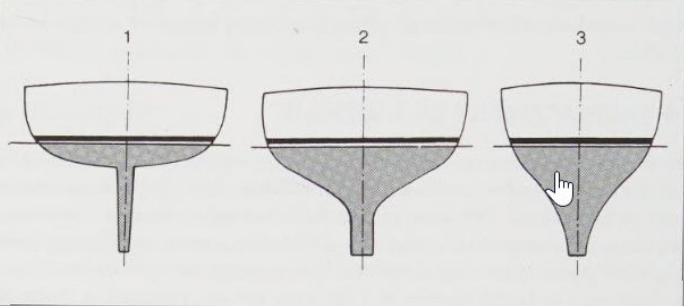

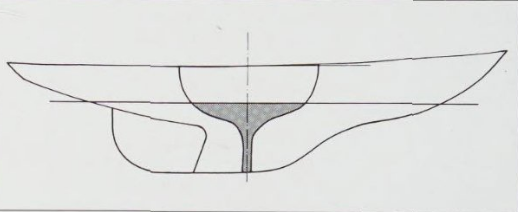

Boats with ballast in their keels should consequently be unable to capsize; that is they should return to the upright position from any situation. A measure of stability is the metacentric height (GM or MG); this is equal to the distance between the yacht’s centre of gravity G (the intersection of the effective line of buoyancy to the heeled central axis of the boat) and the metacentre (M).

For simplification, the centre of gravity (G) and the centre of buoyancy (B) are theoretical points that comprise all weights and all buoyancy.

When the boat is upright, these points are on a theoretical vertical line. If the boat heels, the centre of buoyancy moves to leeward and produces the uprighting momentum with lever h (the line GB). A yachrs stability is therefore dependent on the position of both centres in relation to one another. The stability is made up from the form stability that derives from the hull shape, and the buoyancy scability that depends on the amount of ballast and its position. Modern displacement yachts generally have their ballast positioned so low that they return upright from heeling angles of up to 130 degrees – or more. These boats get stability primarily from a low centre of gravity (large amount of ballast or ballast sited low down in the keel), and the hull shape is secondary.

A wide-beamed hull, with high free board (as most modern yachts are built to provide superior accommodation), has a buoyancy gravity that moves far leeward when heeled and so contributes to the stability. This is why wide-beamed boats with high initial stability are known as «form stable», and narrow-beamed boats that receive most of their stability from the weight of the ballast are known as «buoyancy stable». Despite this, form stability and buoyancy stability always go hand in hand. A slim yacht will always heel more, and consequently cut more smoothly into a rough sea. A wide-beamed boat generally sails much harder and faster at sea and might even provoke seasickness – but the sailing is that much drier.

A boat should therefore only be as wide beamed as required for stability. A good design is apparent from its counterbalanced form and buoyancy stability. Designers have probably put more emphasis on the form stability for coastal cruisers that want to make port every night, while the ocean going yacht will be equipped with more buoyancy stability so that crew and gear will not be stretched too far. Every yacht has to be designed with sufficient stability to enable the sail area required to reach the hull speed to be carried in a force 4 without having to reef.

The designer predetermines a yacht’s characteristics, but you as a buyer should be able to form your own opinion of a boat by looking at its data and build characteristics. This way, you will be able to find the yacht that is best suited to your requirements.

Cruiser or dinghy?

Before looking seriously at Compact Sailing Boats – Key Specifications, Innovative Designsailing yachts, you should know which type of boat you are assessing. To define a sailing yacht and assign it to some sort of class is quite difficult. Although there is a large variety of boats on offer, you will not find a «production-line boatyard» that wants to be placed into one particular category. These days, one can hardly tell the difference between racing yachts and cruiser/racers. This is one reason why cruiser/racers remain popular, although they are undefinable mixtures that are no good for either purpose.

With boats, you have to make similar differentiations to those you would make when choosing a car: between a runaround, everyday or luxury car. In the same way, you can only evaluate a boat correctly when you have determined whether it is a centreboarder or keel boat, coastal cruiser or ocean cruiser. There are specific criteria for each type of boat. For a yacht that does most of its sailing in a sunny climate, the cockpit cannot be too large, while the ocean cruiser’s cockpit should be small for safety reasons (ideally less than 6 percent of the yachts volume).

Similar factors apply to many other areas: double berths, for example, are wonderful for boats that are moored up in harbour every night, but they are useless on ocean cruisers. A racing yacht has adjustable backstays in order to achieve good mast tuning, but on a cruising yacht these complicate the sailing. Every boat must therefore be classified. The starting criteria can be the boat’s type, purpose and sailing area, and from there you can advance to further characteristics. You have to know the purpose for which the boat has been designed, and this question can best be answered by the designer. After all, he designed the boat for a specific purpose.

Although formal classification has not yet been introduced in Britain – and it is not certain quite how it will affect yachts (as opposed to commercial vessels and workboats) – it seems likely that yachts will be divided into these categories:

- Sailing dinghies.

- Cruising dinghies.

- Keel boats (without accommodation).

- Sailing yachts with accommodation.

- Motorsailers.

There is also some argument as to permitted cruising areas, and fittings and equipment required; and also possibly the most worrying point: the question of enforcement. However, at present it is probably fair to say that with very few exceptions, most boats are suitable for the purpose stated by the manufacturer; it is mainly in the matter of details such as:

- hatches;

- windows;

- deck equipment and ground tackle that anomalies occur.

With an older yacht, it would be advisable to consult a surveyor.

What you read in the brochure

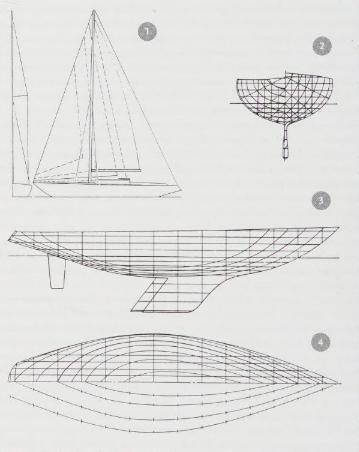

The boat’s measurements define its characteristics: those most easily obtained are the overall length, the beam and the draught. However, the creature is more complex than this: waterline length, displacement and sail area are also specific values, which together form the overall picture.

Length. Surprising though it might seem, the actual overall length of a boat may differ from that given in the manufacturer’s data (and occasionally even from that specified by the designer). The length overall can (and when quoted in brochures, frequently does) include:

- bow platforms;

- pulpits;

- push pits;

- boarding ladders and davits – even transom hung rudders!

This length, though, is defined as the total length, and should not be confused with the overall length upon which calculations such as the enclosed area or volume are made. (Pragmatically though, it is the total length upon which the harbour or marina fees will be levied.) The waterline length is also important, as this will be needed in order to work out the boats maximum theoretical hull speed.

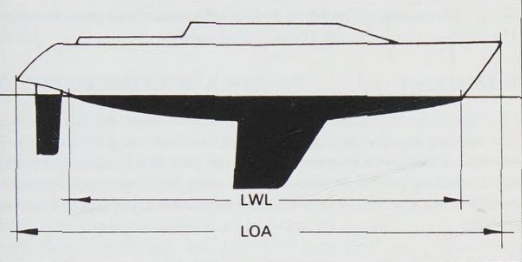

Length overall (LOA). The length overall is taken as the distance from the trailing edge of the transom to the extreme forward edge of the stem. It is measured parallel to the flotation line and excludes any projecting deck fittings. It is always the length of the hull only, and this definition is used by boat builders and designers. A 10 metre boat should be just that – 10 metres – so if there is any doubt, measure it.

Waterline length (LWL). The waterline length is measured at the fore-and-aft ends of the flotation line. The datum (or designed) and actual load waterline lengths frequently differ slightly, but it is the actual load waterline that determines the hull speed in a displacement hull.

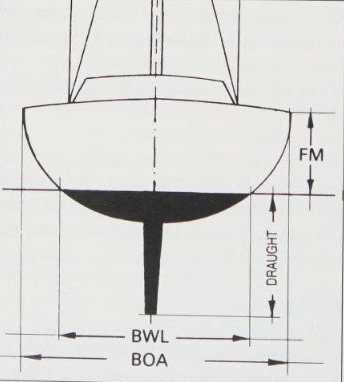

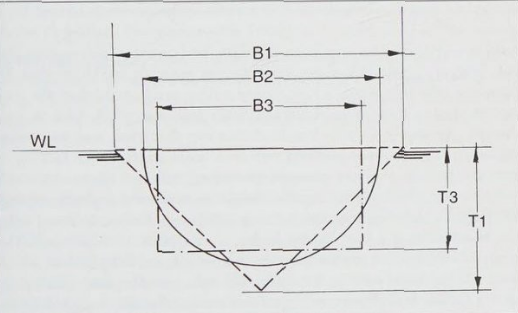

Breadth. A boat’s beam is divided in the same way as its length is: breadth overall and breadth on the waterline. A boat’s breadth gives stability; the beamier the boat, the better is the form stability. Having said this, the breadth also acts as a brake, and designers are therefore concerned with keeping the breadth on the waterline to a minimum.

he cross-section of the boat’s widest part is called «midship section». In vessels with harmonic all-round qualities, it can be found in the middle of the waterline length (0,5 LWL); in small cruisers with wide sterns it is often found in the aft third. This has the disadvantage of giving the boat a lot of weather helm when heeled.

Breadth overall (BOA). The breadth overall defines the largest breadth of the hull, measured from the outer edge of the outer hull, exclusive of rubbing strakes. This measurement, in connection with the hull length, permits assumptions about the enclosed area (volume): the beamier the hull, the more space is below deck.

Breadth in the waterline (BWL). The breadth in the waterline is the breadth of a boat that is ready equipped for sailing, measured on the flotation line. If multiplied with the LWL, it produces a waterline triangle. This is the basis for calculations with regard to the sail-carrying ability of fin-keeler, bilge-keeler and centre boarders. The BWL is responsible for a boat’s initial stability.

Draught. The draught is defined as the vertical distance between the flotation line of a boat equipped ready for sailing and the lower edge of the keel. It contributes to the enlargement of the lateral plan, but hardly at all to the initial stability (stiffness), The draught only produces more buoyancy stability when the boat is heeled sufficiently, i. e. when the ballast becomes effective.

Freeboard. In open boats, the freeboard is the smallest distance between the boat’s flotation line and the upper edge of the gunwale. In craft with a deck it will be measured up to the upper edge of the deck at its lowest part. If a boat’s heeling angle is fairly low, a high freeboard reduces the stability, because a hull that emerges high above the surface of the water also lifts its centre of gravity. The stability increases again through greater buoyancy of the hull, if the heeling is further increased. This becomes especially evident in boats with wide-beamed sections, which have a greater immersed volume when heeled.

Displacement as a weight. A yacht’s displacement weight is the weight equipped for sailing. This weight comprises the dead load, the hull with its fixed parts of equipment, and the extra load. The extra load is the sum total of the:

- persons permitted (approximately 75 kilograms);

- tank contents;

- safety equipment;

- sails;

- personal gear (up to a maximum of 30 kilograms per crew member) and provisions.

Outboard engines and fuel cans are also included in the extra load. Boats are divided into heavy, medium and light displacement. Another term that is common among racing people is «ultralight» – which is pretty much self-explanatory.

Displacement as a volume. The displacement in the water describes the volume of a yacht that is equipped ready for sailing, up to the submerged flotation line. It is the quotient from displacement (D) and density of the displaced water (density of sea water = 0,975). Boatyards often advertise a yacht’s displacement in their brochures, but it generally means the dead weight of the boat without equipment. (If you want to trail your boat, you must know its dead weight and the tow capacity of your car. Beware though – manufacturers’ estimated weights are notoriously inaccurate. If in doubt, head for a public weigh bridge to check.)

Ballast. The ballast describes the part of the displacement that contributes to the (weight) stability as either external ballast (contained in the keel (or keels) or internal ballast (within the boar). It enables a boat to carry sails. The most common ballast is lead or cast iron, and for a cruising boat the weight should be between 40 and 50 percent.

Sail Area. When comparing sail areas you will generally find the close-hauled sail plan stated: on masthead rigs this is the sum total of mainsail and 150 percent genoa. This represents a fair definition for the narrow mainsail and enormous foresails. It also enables a comparison between masthead-rigged and fractional-rigged (7/8-rig) yachts. For this, you calculate the main and the largest foresail without overlap, which is generally the № 1 jib.

The yacht’s qualities

To the majority of intending boat owners, the performance of the yacht will be of prime importance. Although a boat cannot be assessed in precisely the same way as a car, its behaviour is similarly the result of a number of components designed to work together in harmony. As with a car, your requirements must be clearly set out in your own mind; and (as with cars) there will be certain compromises that must be accepted.

In the case of a sailing boat, such compromises will tend to lead you towards a particular type of yacht: perhaps a motor sailer whose performance under sail alone is secondary to on board comfort and economy and ease of handling under power; or possibly a fine-lined yacht – one that inclines to be tender, but that points high and sails fast (though in so doing, will give the crew a wet ride); or, a third option, the maligned «floating caravan» – this will have above average accommodation for the overall length. This latter option may require a bit of determination by the skipper to persuade the vessel to reach the maximum hull speed, but (though it may tend to slam into head seas) it will, nevertheless, prove quite stiff and dry.

A good deal does depend on your cruising area: if most of your sailing is in the Baltic (in summer, that is!) or in the Mediterranean. lighter construction would be acceptable – and a large cockpit and generous sail plan would be handy. However, if sailing in exposed waters, the boat must be strong, the cockpit small and well protected, and the vessel able to keep to the sea in a gale if necessary. It must also point well enough to windward to be able to claw off a dangerous lee shore. A rig should be easily handled and all the deck hardware must be to the highest possible specification. In tidal rivers and estuaries, the ability to short tack quickly is a real asset, as is a hull form that does not lose way in a short, steep sea. (Shallow or variable draught is often useful in these areas, too.)

Of course, there are some qualities that every yacht should have: the ability to tack clear of a lee shore if an onshore wind threatens to push you on to the coast, and sufficient stability for righting even from extreme heeling angles.

Fast Sailing

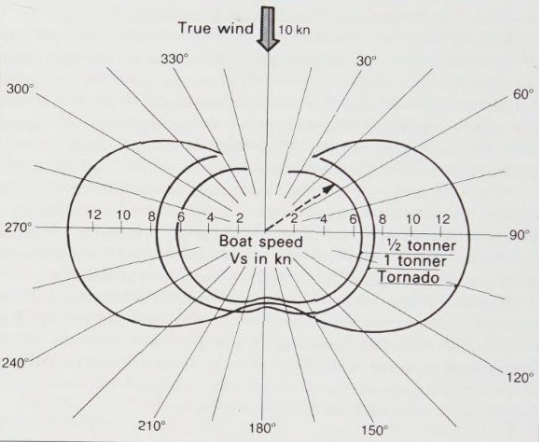

A yachts speed depends primarily on wind force and sail area. We are now talking about qualities that the designer selected in order to make the boat comparatively fast.

The factors that influence a boat’s speed are various, The brochure may already present some factors that can be derived from a boat’s measurements and used for later calculation:

The length of the waterline: The longer the LWL, the higher the maximum speed (see Hull speed higher).

Displacement: The lower the displacement, the flatter can be the hull shape and lines, and it requires less wind to bring the boat up to hull speed. The relationship of the displacement towards the waterline indicates the wave-producing length and also shows whether a boat is light or heavy.

The wetted surface: Defines the area that is submerged in the water and can roughly be estimated from the vessel’s length, beam and draught. A yacht will sail faster in light winds, given a lower wetted surface. In stronger winds, the proportion of the friction resistances (see higher) decreases from the overall resistance, thus it outweighs the wave resistance. Narrow, deep fin-keelers only have a small submerged surface, and are therefore good in light winds.

The next two factors cannot be obtained from the brochure. They need to be calculated; this will be explained in a later chapter, but is worth mentioning at this point in order to complete the list:

The stability is a function of sail area, displacement and breadth on the waterline, The higher the stability, the more sail area can be carried and the faster the boat will sail. The yacht’s sail-carrying ability therefore derives from the relationship between sail area and displacement.

The cylinder coefficient is explained in the Appendix/ (p97), but it also needs mentioning here as there are some boat dealers who boast of it. It is a measure of the distribution of a yacht’s submerged volume across the hull length. The higher this coefficient is, the more wind is required for a yacht to reach the hull speed.

If you are looking for a cruiser, you should put a lot of emphasis on the length of the waterline and stability, but less on a lower cylinder coefficient – which only makes the yacht more tender. A comfortable but heavier interior layout with an additional 50 kilogram ballast is usually more important for a pleasant sail that 50 kilogram placed in the keel, where it would increase the boat’s stability and allow it to carry more sail.

Boatyards are aware of this, and in most cases only build the first boat of a series fast (minimal interior layout, no equipment). The weights stated in the brochure are subsequently only correct for this one particular vessel. Only a yacht that is empty will float on the designed waterline. If you buy the version with two WCs, aft cabin and fully equipped galley, your boat would lie 4 centimetres deeper in the water and consequently not perform as stated. This is why you should be very cautious of so-called cruiser/racers.

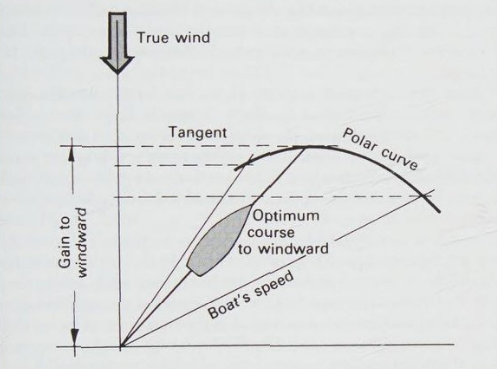

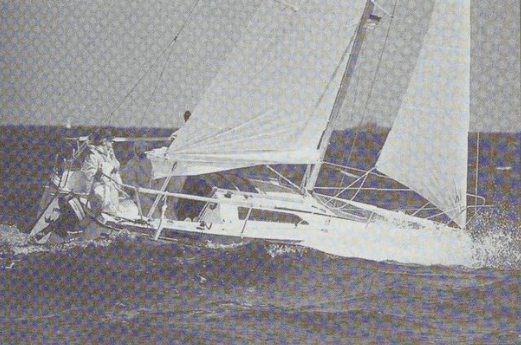

Sailing to Windward

The height to the true wind is defined as the angle that a yacht can sail to windward. In practice, it is the tacking arc measured at the true wind divided by two. Statistics show that a yacht only sails close-hauled for a quarter of her time (though it doesn’t always seem so!). Sailing to wind-ward is nevertheless an important criterion, and one in which rigging and sails also play a part. A cruising yacht cannot generally sail closer than 40 degrees to the true wind, which means sailing nearly a third of the way farther than a motorboat driving directly into the wind. Out at sea, though, the ability to sail close-hauled is not that vital, and it is more important for a yacht to perform well on a beam reach. When tacking in narrow channels or rivers, though, every metre, clawed up to the wind, really counts. Although the expected height to windward depends strongly on the hull’s hydrofoilic qualities, it is a combined effort of hull and sails.

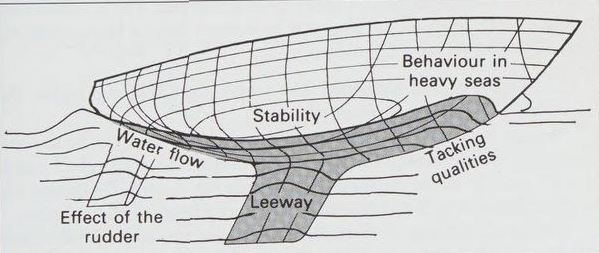

The narrower a boat is, the higher it can point to windward. The origin of this opinion derives from the relatively heavy long-keelers, which have a large lateral area in the water and subsequently make less leeway than a beamy hull. Hydrophilic qualities are also known as lateral buoyancy. A good lateral buoyancy, thus good lateral force, represents smaller drifting angles, i. e. less leeway.

Despite this, there are wide-beamed full hulls that can point just as high, or even higher, than a narrow boat – so long, that is, as they are sailed upright and with caution. These hulls obtain their lateral buoyancy from a profiled fin keel and equivalent fin rudder (these are so-called NACA-profiles that originate from tank testing and are especially suitable for yachtkeels). The following rule applies for these fins (or hydrofoils): the higher their aspect ratio – i. e. the longer and narrower the hydrofoil (fin) is and therefore the larger the draught – the smaller is their drifting angle. A well-sailed yacht can point up to 34 degrees to windward with these fins. One condition that is necessary to obtain such high pointing is a clean water flow at the fin, which requires a smooth transition to the hull (flat bottom) and an often bulged lower edge of the keel (or even a winged keel) as a so-called «endplate». The effect of this is to prevent the flow at a end from drifting away. These boats, though, are more difficult to sail, are very unforgiving of mistakes, and are generally not very course stable.The flow around narrow keels cuts off a lot earlier, so that finding the most efficient course is more difficult. This is why a boat with a Keel Types Comparison and Additional Design Considerations for Sailboatsnarrow fin keel can only sail close to windward when it has sufficient drive: in lighter winds becomes necessary to bear away more in order to keep way on. The following example displays what a good speed, together with good lateral height, means for sailing close to windward (i. e. for the ultimate course to windward). One should consider this prior to buying a yacht: the helms-man of a yacht has no reason to gloat over the dinghy helm because he is able to point 35 degrees to windward and the dinghy only points 45 degrees.

The yacht’s route might only be 22 percent longer than the direct direction into the wind, while the dinghy’s route is 41 percent longer; however, because of the speed, the dinghy will still reach its destination a lot faster – final speed to windward is higher. Speed and height to wind-ward are therefore directly related to one another and cannot be separated. Important for a good performance to windward is therefore the boat’s final speed to windward, generally described as Vwindward, which should be as high as possible in each wind force. This angle is the product of speed and the cosine of course angle. The upper part of Fig. 13 clarifies the relation of speed and course angle. It is therefore not worth your while aiming for a boat that can point extremely high; what you need is the optimal course with the better final speed to windward. It is therefore not vital for a cruiser to have an extremely narrow and deep fin; boats with a medium cut-away keel that have less draught, or even boats with a conventional long keel, will achieve good final speeds – and also have the advantage when approaching shallower harbours.

Manoeuvrability and Course Stability

Many sailors are convinced that to combine good manoeuvrability with acceptable directional stability is an impossibility, In the more extreme examples of fin-keeled racing boats, responsive to the slightest twitch of the rudder, this does hold true – such boats cannot be left to their own devices even for a moment. However, this type is not designed – or, equally important, constructed – with passage-making in mind. To take the other extreme, though, the «traditional», directionally stable, long-keeled cruising boat (which admittedly takes its time in answering the helm) is not the only type of cruiser – nor, arguably, the best all-rounder.

The best all-rounders are generally yachts with medium fins, whose lines, if extended, would be like those of a long keel, but where section aft has been cut away (cut-away keel). This is why one talks about an interrupted lateral plan in connection with these boats. A modern yacht that has such a fin keel (albeit of less extreme form than a racing yacht), with a skeg in front of the rudder, can be both stable and manoeuvrable.

The long, continuous lateral plan of a long keel is definitely less sensitive on the rudder because of its larger inertia. This makes it more suited to ocean cruises. However, for navigating narrow harbours and marinas, you need a boat that is easier to manoeuvre.

Looking at a long keel, you will find that it has a good deal of submerged surface – hence increased friction resistance. The connected braking effect will therefore be especially noticeable in light winds. (Narrow long-keelers with an S-section compensate for this by their lower proportion of wetted surface.) Thus yacht designers shortened the length of the keel, which led to the so-called «interrupted» or «divided lateral» profile. (Subsequent shortening led to the small fin keel with a large draught.)

If such a keel is to assist course stability it must possess a good keel-to-rudder alignment, so that the lateral force and the force of the rudder counterbalance the pressure of the sails, even at different heeling angles. Unfortunately, you will not be able to detect this at first glance. Cut-away keels are more suitable for cruisers, as they are more forgiving of errors – both those made by the designer and, later on, those made by the sailor!

Fin keels are not only effective by virtue of the size of the area, but they also obtain their required lateral force from the profile and thus need more speed through the water. A narrow fin also needs to be correspondingly thin, but there are limits because the attachment must be strong. The keel must also carry the required ballast. Extremely narrow fin-keelers are there-fore not suitable as cruising yachts, since the crew must perch on the windward side; their advantage, though, is very good manoeuvrability. Since this is associated with a very sensitive helm, the tiller cannot be left unattended even for a brief moment.

A narrow fin-keeler can only regain its more user-friendly qualities if it has a skeg in front of the rudder that is about half of the profile area of the rudder blade itself, as well as a slim, deep bow. A long keel obtains its lateral force almost solely from the front half of the lateral plan. Behind that, this is so negligible that it can be dismissed, and so designers cut away this section in order to minimise the wetted surface.

Short-keelers can combine manoeuvrability and directional stability if designed properly, but keels that are particularly shallow have another disadvantage: the buoyancy of the fin is reduced drastically when going about at a low speed (it depends on the square of the speed). The boat loses way – and therefore the fin becomes less effective – if it is not driven with a sufficiently large angle of incidence. You can often observe these yachts drifting sideways in harbour as they attempt to gather speed.

This disadvantage is reduced by building deeper keels, because the lateral buoyancy also increases with the square of the draught. In contrast to this, though, are the desires of sailors to be able to enter any harbour: the draught of a cruising yacht should therefore not be allowed to exceed 1,6 metres. Extremely short keels tend to tilt on to their noses when dried out – and are also very sensitive to contact with solid ground. This results in a requirement for a cruising yacht that is as easy to manoeuvre as a fin-keeler, but at the same time directionally stable; and this can be a difficult compromise for the designer – and the buyer.

Stiffmess

A «stiff» boat is also a boat with good stability; but, despite this, stiffness should be defined differently. A stiff boat does not heel quickly in a gust of wind and hardly moves when somebody steps on to the deck. Both of these factors seem positive at first glance, because they give a feeling of security. However, the question that should be asked is whether a tender boat (the reverse of stiff) does not have the better qualities at sea.

The stability of a boat comprises, as already mentioned, form stability and buoyancy stability, interpreted as the heeling angle up to the point of capsize. The stiffness depends mainly on the boat’s initial – and therefore form – stability. This is because the ballast only becomes effective in heeling angles with sufficient leverage. At heeling angles of up to 30 degrees, the form stability determines the stiffness of a boat. With beamier boats, the stiffness is further increased with a correspondingly higher metacentre M above the water surface. The actual factor for the form stability is the shape of the hull. The beamier the sections, the more additional volume is brought into the water – thus the stiffer the boat. This quality, which was initially judged as positive, leads to uncomfortable behaviour at sea. The consequence of too much stiffness is jerky movements and smashing into waves, which is demanding upon both hull and crew.

Slim boats with a large amount of ballast might heel more quickly, but their deep hulls (more buoyancy stability) react more sluggishly. This makes them more comfortable for the crew at sea.

Wet or Dry?

One desirable quality of a cruising boat is that it should, even when sailing hard, refrain from scooping up water and throwing it over the long-suffering crew. Whether or not it does this depends upon the stability and also the buoyancy at the bow and stern (which should be balanced to a large extent, for otherwise a pitching moment will be exaggerated). A narrow boat, with low initial stability, will heel sharply and put the gunwale under with great alacrity – although given a cockpit, well protected by high coamings, this may not bother the crew unduly; after all, not much in the way of solid water will actually reach them. A yacht with a high freeboard will, naturally, have correspondingly less water on deck even at a high angle of heel.

However, a good deal of the water that may come aboard is the direct result of the boat sailing fast and burying the bows in the waves; this is the result of a lack of buoyancy forward – and boats with a fine entry coupled with deeply vee’d sections forward are very prone to «undercut», especially in a head sea. A certain amount of «flare» – an outward curve to the top-sides, so that the beam at the gunwale is greater than it is on the waterline – will tend to fling water clear, and it also increases the buoyancy forward as the vessel heels. It does, however, increase drag, since the deck edge, along with the toe rail, stanchions, etc may be immersed as heeling increases. Sometimes a knuckle is moulded into the topsides to serve the same purpose (and also to stiffen the topsides of a fibreglass boat), but this hardly enhances the appearance – and, once again, can create additional resistance.

Simplistic though it is, the basics hold true: fast boats wet, slow boats dry. However, in strengthening winds, there will come a point when a beamy boat, sailing at maximum hull speed, will be as wet as any fine-lined boat – although high freeboard and superstructure may keep the crew more comfortable.

Seaworthiness

Every prospective buyer is entitled to expect his or her yacht to be safe at sea ~ in other words, to be seaworthy. How is seaworthiness defined, though?

Well, clearly, it is more than a matter of bull design; for a start, the yachts construction must be strong and structurally in a sound state. The design of the cockpit must be carefully thought out: it must be large enough to seat the crew on watch, protect them so far as is possible from the elements, and allow them good all-round visibility; it should also (preferably) be self-draining. Windows and hatches must be watertight and, where necessary, capable of being secured against a capsize or total inversion (many «cruising boats» have hatches and skylights that are insubstantial and far too large for safety). Deck fittings and ground tackle must be adequate for the size of the vessel and, of course, the rig must be strong, well supported and easy to handle under any circumstances. Such a boat should be able to withstand heavy weather and ought to be capable of making some progress to windward in all but the very worst conditions. It would be expected to remain controllable and to lie hove-to in a gale – hopefully, too, it should be blessed with an easy motion in a seaway, though there are some circumstances in which this might seem a bit over-optimistic. Needless to say, to be regarded as seaworthy, any yacht must also possess sufficient stability and righting ballast to recover from a knock-down.

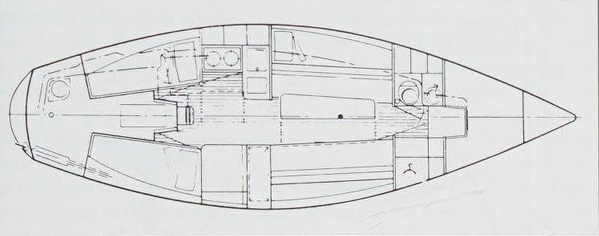

A sound cruising yacht must also have a well-planned layout below; this does not mean accommodation that is crammed full with luxuries, but rather one that provides a fixed berth for each off-watch crew member, an efficient cooker (preferably fiddled and hung in gimbals), and enough space to use it safely (much the same goes for the WC, incidentally.). There should also be a stable chart table – ideally one that is large enough to spread out a complete chart.

Such qualities are a lot to expect from any boat, yet working craft such as sailing crawlers, the Bristol Pilot Cutters and the famous Colin Archer-designed rescue boats have all managed to combine them – and without the benefit of modern technology and computers. The design of these craft is not only functional but also beautiful, both above and below the waterline – with soft sections merging into the long keel and well-balanced ends. (Well-balanced, in this context, means that the fullness of the under-body is amidships and the sections of bow and stern are reasonably – and this is important – similar to one another in volume.) Hulls undistorted by rating rules and free from the extremes of sawn-off transoms, snubbed bows and peculiar midships bulges represent the best of cruising boat design and are unlikely to exhaust the crew by violent motion in a seaway. Also, a hull with harmonious ends is less likely to develop lee or weather helm when heeled, and so should maintain a course easily – without tearing the helmsman’s arm from its socket, or flattening the battery of the autopilot.

In comparison to boats like this, there are extreme racing boats whose hulls are very light and intended for speed and nothing but speed (though usually each is designed to perform optimally within a given range of wind strengths, few are outstanding all-rounders). All these types are very hard to control and cannot therefore be regarded as seaworthy – even when they are strongly constructed, which is rarely, if ever, the case.

With practice, you will be able to recognise a yacht whose shape is well balanced and harmonious. Of course, back in the days when most boats were constructed of wood, such was nearly always the case – indeed, the nature of the material itself forced designer and boat builder to produce vessels with sweetly flowing lines. Timber planks, after all, do not take kindly to distortion and it is all but impossible to build the type of form currently engendered by the rating rules in carvel or even clinker strakes, although it is possible with moulded veneer.

However, along came computers – and high-tech boatbuilding – and sections and sterns sprouted bumps, blisters and bustles, all in order to improve the rating. The pity of it is that cruising boats followed suit for no logical reason other than fashion. Many of these boats, more or less directly derived from competitive craft, were (and are) designed without any consideration of the waters and wave systems in which they will sail. Neither are these boats pleasing to look at – and there’s a lot of truth in the old maxim: if she looks right, she’ll sail right!

In comparison to these boats, you find extreme designs for racing, whose hull shapes increase their sail area. They are fitted out with all possible features simply to increase speed. These boats are hard to control and therefore not seaworthy.

With a little bit of practice you will be able to recognise a boat with well-balanced lines: in the days of wooden yachts, these lines came naturally. Planks of wood bend in curves – and only in curves! These curves seem pleasant to look at because of their even and harmonious proportions. The flow of the water is harmonic too. A beautiful and well-balanced hull also sails well. To recognise the beauty of a boat’s hull is part of its evaluation.

Behaviour at Sea

Wind and waves deal harshly with a boat: they accelerate it, slow it down, and cause it to dance on the water – the rougher the sea and the smaller the boat, the worse it is. Unfortunately, not every boat can be built as large as an owner might wish: financial considerations and ease of handling are also limiting factors. However, there are design features that allow a smaller yacht to counteract these unpleasant movements – or at least do not exaggerate them, e.g., a slightly higher displacement, well-balanced stability, and not too flat a hull shape.

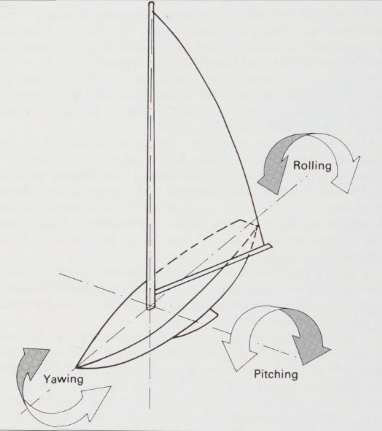

The main oscillations of a boat in heavy seas are pitching, rolling and yawing. A boat is rolling when it moves from side to side along its length axis. (This is often supplemented with diving movements that further increase the angle of rolling.) The designer can restrain this by building a hull shape with more lateral buoyancy, as this counteracts the rolling to a certain extent.

A pitching boat moves rhythmically around the cross axis (up and down), which becomes worse the more it integrates into the wave system. A well-designed yacht can reduce the pitching by concentrating as much weight as possible around the centre of gravity and with a finer bow area that cuts more smoothly into the water.

Yawing is a rhythmic rolling movement around the vertical axis (around the mast, so to speak). Yawing subsequently leads to broaching. Good course stability reduces the yawing movement – for this you require good alliance between keel and rudder. Long-keeled yachts display a reduced tendency to yaw – short-keeled boats should therefore have a skeg. You should pay attention to these features if purchasing a cruising boat. A cruiser should be expected to reduce these three oscillating movements by using the slowest possible acceleration – it is the abrupt changes of speed that make a yacht unpleasant to sail. If these movements cannot be endured, the crew will not be able to sail the boat safely, let alone enjoy the sailing. Today’s modern yachts, which are generally flat and bowl-shaped, are exposed to the forces of the sea because of their tendency to skitter along the surface of the water.

While earlier yachts had roughly two-thirds of their hull submerged in the water, the cruiser/racer concept seems today to favour the reverse. These boats might have become faster, but their rolling and pitching movements are so short and undiminished that the boat often accelerates far too fast. Under such circumstances, seasickness is likely even in light winds. The best cruising yacht is the one with the smoothest movements: these can only be founding yachts with harmonious hull shapes.

Accommodation

An additional safety aspect is a modicum of comfort aboard, because only a rested crew can sail safely over long periods. In comparison with racing yachts, cruising yacht interiors are generally fitted out with teak or mahogany. Most of these layouts are only practical when in harbour, and are unsuitable for sailing. They feature double bunks that are useless when the boat is heeling, galleys with ill-fitted attachments for the cooker – not to mention the seating spaces below deck whereby the crew sit on each other’s laps even when still in harbour. The sailing performance also frequently suffers because of too much internal weight: two WCs, a shower, an over sized cool-box (possibly a generator) and other shore comforts, none of which is strictly necessary. A limit should be placed on interior fittings, otherwise performance may be affected.

The ideal layout should be functional for passage-making and habitable in a harbour. When buying a yacht, you should choose the layout that fits your own personal requirements. It depends on the type of boat, but even mass-produced boats are subject to change – within limits, of course.

Some people are under the impression that the interior layout is designed by sailing people; unfortunately this is seldom the case. More often than not, functionality has to give way to more bunks, and boatyards reduce the bilge section in favour of sufficient headroom. By limiting the bunks to the number actually required, a sensible layout could be designed so that areas where headroom is required, i. e. galley, WC and passageways, can be placed where headroom is available: next to the companionway. Other concepts can be achieved through wider beam, cambered decks or even raised decks. Sitting headroom is sufficient above bunks and seats. Because of the lower hull depth of modern light constructions, the height of the freeboard has been increased, which is no disadvantage for larger boats as it raises the buoyancy. However, to try and create headroom on a 6 metre boat and then sell it as a cruising yacht is irresponsible. If you are thinking of purchasing a mini-cruiser, you should be sceptical.

Even on larger yachts, the interior layout can influence a boat’s qualities. It is always a disadvantage if too much solid wood has been used for the interior as this only lifts the boat’s centre of gravity. Extra attention should also be given to the fact that there are heavy bunks in the forepeak, and the nowadays common double bunks in the aft cabin, cause unnecessary pitching when under way; always remember that as much weight as possible should be concentrated around the boat’s centre of gravity, i. e. in the middle.

Double bunks have become increasingly popular at boat shows. They might be very comfortable for the nights spent in harbour, but narrow bunks are required when under way so that the sleeper can be wedged in. Double bunks should only be tolerated in the forepeak, and even then they should be designed as light pipe cots. The forepeak is not generally ideal for sleeping under way because of loud noises and uncomfortable movements. All other bunks should be single bunks, which should be already made up (no lowering of tables and so on).

Most suitable for sailing yachts are pilot berths on the sides and quarter berths, although they should be easy to get in and out of.

Read also: Popular Types of Yacht

Diagonal berths are totally unnautical as they are highly impractical: when the boat is heeled, the occupant is either standing on their head or on their feet. If double berths cannot be avoided, they should be separated with a lee cloth. Even if you do not intend to set out in a gale, your boat should still be furnished sensibly. Whether the interior design is to your personal taste is often only determined after a holiday afloat. By looking at a few details, though, one can normally quickly establish whether the boat has been designed by sailors (handrails, fiddles, seagoing berths, etc). A good interior design contributes towards good sailing performance if it is of fairly light weight, and preferably placed around the centre of gravity.

Safety

When questioning the safety of a yacht, the thought uppermost in the mind is usually «Will the craft capsize?» Hard on the heels of this, an intending purchaser might well ask, «Will it sink?» With boats there are no absolutes, of course, but it is certainly possible to design and build a yacht that is, theoretically, unsinkable. In the case of a light displacement boat, whether of timber or fibreglass, buoyancy tanks can be inbuilt, and it does not need much positive buoyancy to counteract the relatively small amount of ballast on such a craft. Given a displacement cruising boat witha ballast keel – perhaps accounting for just under half the total weight – and an engine, cooker and all the paraphernalia of passage-making, it can be seen that the equation is more complex. However, it is possible – or, more accurately, it is possible with a fibreglass boat and at the time of construction. Foam is injected between inner and outer hull skin, under berths, and often in the bilge space. Foam or balsa core construction also add some positive buoyancy. Integral foam entails a sacrifice of stowage space, but this is a small price to pay for peace of mind. However, it is difficult (if not impossible) to fill and bond foam to cavities once the hull has been built and, for constructional reasons, not advisable to do so in a timber boat (certainly not with one of «traditional type»). Later on, if there is any injury to the external hull, the presence of the foam will make repairs both difficult and expensive. Air bags are another alternative; however, they must be carefully sited and attached to strong points so that they cannot break loose and (literally) tear apart the hull and deck of a waterlogged boat.

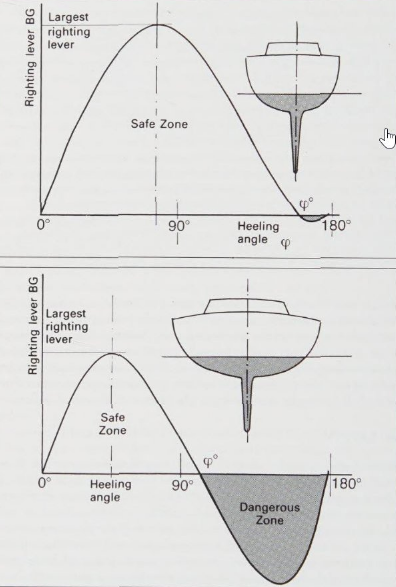

As for capsizing – well, it is a fact that there are circumstances under which any boat can be knocked down (a knock-down is where the boat is flat on its side, with the hull at 90 degrees to the surface of the water). Indeed, this is not even an uncommon occurrence, particularly where racing boats are concerned. Far more serious is complete inversion, though this is usually the result of freak conditions and is fortunately far less common. Although, as has already been said, it is impossible to give an absolute guarantee that such disasters will never occur, they are very unlikely in a well-designed cruising boat with good lateral stability and a high reserve of buoyancy inherent in topsides and superstructure. A keel boat, whose hull measurements are within normal parameters, will (so long as the ballast calculations are correct) always right itself from a knock-down and even after a complete inversion (but in either case this is dependent upon a watertight hull with hatches and flushing boards remaining in place). The speed with which the boat returns upright depends on the position of the centre of gravity G and the centre of buoyancy B for every heeling angle. This is the basis of the so-called «still water stability», displayed as a curve. Applied above the heeling angle, it displays the height of uprighting moments.

When the curve cuts through the line of the heeling angle it is divided into two zones, the one above the heeling angle is the safe zone and the other one the dangerous zone. The intersection is known as the «negative stability» (point of capsizing). It is easy to establish a yacht’s stability by using this curve, but unfortunately you will not be able to obtain it as a buyer, you have to rely on the designer. Generally speaking, it can be said that boats with long keels and a low centre of gravity (which can roughly be estimated from the proportion of ballast) are far less prone to capsizing than modern designs with flat underwater hulls and fin keels. Cut-away keels and long-keelers are also generally capable of righting themselves if they turn turtle. This is precisely what wide-beamed boats with a shallow bottom do not do; they remain upside down for minutes and only the impetus of a wave or something similar will turn the boat back vertically. A structure of large volume that supplies buoyancy after the capsize would change this. Many cruiser/racers have flush decks (thanks to their origination from racing yachts) and this makes things worse.

So much for the static stability that is important in still water – unfortunately, the dynamic stability is harder to detect. Consequently, little is known about it. One thing, though, seems definite; the larger the yacht, the more force is needed by the breaking sea in order to capsize it. In order to capsize a 9 metre boat, you would in theory need a 6 metre high wave. Light yachts are especially susceptible to capsizing as they accelerate faster. A high freeboard, which is an advantage for the static stability, offers a larger attacking area for the waves. What about the fin keel? Dynamically, it has the advantage of stalling less in breaking seas than a long keel does (as described in many experience reports), but once the yacht has been knocked down, the static stability takes over and thereby it is important for a yacht to return to its normal sailing position. These aspects should also be criteria for consideration when you are deciding which boat to buy. A light fin-keeler, in spite of its size, should only be recommended for sailing along safe coasts in the hands of experienced sailors.