Compact Sailing Options offer a perfect blend of efficiency and maneuverability for sailors of all experience levels. These boats are designed to maximize performance while minimizing storage and transportation challenges. Ideal for coastal cruising or weekend getaways, they feature innovative designs that enhance stability and speed.

With lightweight materials and compact dimensions, navigating tight spaces becomes effortless. Whether you’re looking for a solo expedition or a family outing, Compact Sailing Options provide a versatile solution to your sailing needs. Embrace the freedom of the water with these exceptional vessels.

The Day Sailer

In viewing small boats at the winter boat shows, we are astounded by the range of quality offered to the small-boat sailor. In unballasted centerboard or dagger board boats between 10 and 20 feet, the number of poor-quality boats is appalling, which makes it especially important to know how to judge the quality of a small boat.

Perhaps the builders of these small boats assume that their boats will never be tested in rough weather. This assumption is dangerous, first because an unexpected squall can test a boat’s seaworthiness even on the smallest of lakes; and second, because as the small-boat sailor improves his level of skill, he may actually prefer sailing in a strong breeze and testing his boat to its limits. A cheaply constructed boat can literally come apart at the seams in marginal conditions.

There are a few general points to keep in mind when shopping for a small boat. Most of the poorer quality small boats come from smaller builders. This does not mean that all small builders produce poor boats, but give special scrutiny to boats from builders you are not familiar with.

A boat which is a popular one-design racer is often a safe bet, because most of the bugs have been exposed by the rigors of hard racing and hopefully corrected. Another advantage of a popular one-design is that it should be in demand when you want to sell it. Remember, however, that its design may relate to ancient history; ask how long the design has been in existence, and what changes in the class rules have taken place over the years.

In addition to these generalities, here are some of the specifics you should look for:

Design Considerations. Safety is the foremost consideration in choosing a small boat. Realize that, sooner or later, any small boat is going to capsize. When that happens you want to be able to rescue yourself.

A small – should be self-rescuing. For a boat to be self-rescuing, it must have substantial watertight compartments evenly distributed throughout the boat. There are a number of ways to achieve this including a raised cockpit sole or double bottom, or sealing off the cockpit seats and bow and stern compartments. No matter how watertight these compartments may seem, they will always leak slightly. In case leakage should become severe, or if the boat should be holed, you will need additional flotation. This can be achieved with core construction (the core adds buoyancy) or with plastic air bags hidden inside the compartments.

The centerboard or dagger board should be rigged with a preventer to keep it from falling back inside its trunk should the boat turn turtle. A self-rescuing boat can be righted with little or no water in it, so you can climb in and sail away. However it also has a tendency to turn turtle. You cannot right it if you cannot lean on the centerboard, and you cannot lean on the centerboard if it has fallen into its trunk. Also, the rudder should have a lock which prevents it from falling off when you are upside down.

A foam-filled mast is a good idea because it also helps to prevent the boat from turning turtle, although it means that the halyards must be rigged externally.

Automatic self-bailers help keep the cockpit dry in rough weather and, hence, help prevent capsizes. Metal bailers are far more durable than those made of plastic.

Remember that the beamier the boat, the more difficult it is to right from an inverted position, Catamarans are difficult to right due to their extreme beam. With a beamy monohull, it can be hard to break the vacuum formed inside the hull if it turns turtle.

Sails. Many small boats have sails made of lightweight stretch sailcloth. Try to stretch the cloth on its bias (the diagonal between the thread lines), with your fingers. If it distorts and does not return to its original shape, it is too stretchy.

Watch out for small, lightweight corner patches with under-size grommets.

Make sure the mainsail’s bolt rope is hand stitched or attached with a sail slug to the head and clew corner patches.

If the seams are sewn with a single row of stitching, the stitching should be done with a three-throw machine (three holes per zag).

Multicolored sails may look racy, but the dying process weakens the cloth. Different colors stretch at different rates so, after time, the sail can loose its shape.

Rigging. Spreaders should have a limited swing or be fixed in place. A spreader which swings through 180 degrees can allow the mast to over bend in the forward direction upwind, or invert when sailing downwind. Spreader brackets which limit swing must be strongly attached to the mast.

Spreaders should deflect the shrouds outboard, not inboard. Many boats have spreaders that are too short.

Shrouds should be terminated in a swage, not a Nicopress sleeve. If a Nicopress is used, it should be doubled. Boats heavier than 600 pounds, or longer than 18 feet should have shrouds of 1/8-inch wire, not 3/32-inch wire.

Be wary of masts with flimsy sections. With the rigging taut, grab the mast at the gooseneck and shake it sideways. If it’s a «noodle», it will be obvious.

Goosenecks, boom vang, and their fittings are almost universally too light. The boom vang is essential for proper control of the boat in a strong breeze, both upwind and downwind. A tight vang puts tremendous stress on the gooseneck.

The gooseneck should be securely fixed, not sliding in the sail groove; it should be constructed with long welds, not simply with tack welds. The vang must be attached to the boom and to the mast with equal strength. Aluminum pop-rivets will soon pull out. The vang’s boom strap should be wide enough to distribute the load.

Hulls. Watch out for flexible mast partners on boats with keel-stepped masts. The partner should be strong enough for you to stand on.

Chain plates are commonly attached to eyes traps which are bolted through a rolled gunwale. Washers on the nuts are not sufficient; the bolts must have a long backing plate or they will tear through the gunwale.

The hull-to-deck joint, where exposed on a rolled gunwale, should be checked for voids. Poke a knife into the compound in the seam; it should be slightly flexible but should not flake out. Rigid glues will crack as the boat bangs against a dock and leaks will develop.

If you plan to launch the boat off of a beach, ask yourself how easy it is to carry it. Rolled gunwales provide a good handhold.

If the centerboard or dagger board trunk stands unsupported in the cockpit, check its strength by pulling on it sidewaysas hard as you can. It should not move.

To check hull stiffness on a stayed rig, grab the head stay, put your foot on the bow and pull hard. If the hull dimples under the chain plates it is not very stiff.

Manufacturers’ published hull weights are sometimes on the optimistic side. With the cheaper boats, hull weights can vary up to 25 percent from the published weight. If you plan to race, or if you are buying a one-design and may some day sell it to a racer, it is a good idea to weigh a selection of boats and choose the lightest one.

Deck Hardware. The rudder should fit snug in its rudder head, and the center-board or dagger board should be snug in its trunk. They should both be stiff and preferably of airfoil section. Watch out for thin, bendy aluminum plates.

Rudder heads should be made of aluminum, rather than wood. They should cover as wide an area of the rudder as possible, yet the rudder head should not be so heavy that the rudder will no longer float if it is dropped overboard.

Rudder pintles and gudgeons are often undersized and poorly secured to the rudder and transom. Compare fittings with those on a boat of known quality. Remember, the Jess experienced a sailor you are, the more strain you put on a rudder and its fittings, so you cannot skimp here.

Watertight buoyancy compartments must have drain plugs because water will inevitably get into them. The screw-in type plug works better than the lever-handle type or the half-turn bayonet type.

Plastic clam cleats usually do not last a full season. Aluminum clam cleats or cam cleats are much more durable.

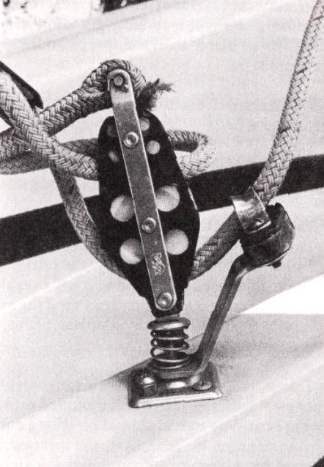

Look for quality blocks and cleats. You cannot go wrong with Harken fittings, but most manufacturers use cheaper hardware.

Take a look at the jib sheeting arrangement. Are there tracks or is the lead fixed? A cam cleat mounted on the leeward rail is the simplest cleating system to operate, providing it is mounted on an inflexible base and angled so it will operate properly from the windward rail. Sit in the boat and see if the angle is right. Beware of cleats mounted on thin stainless plates, because the plates bend easily.

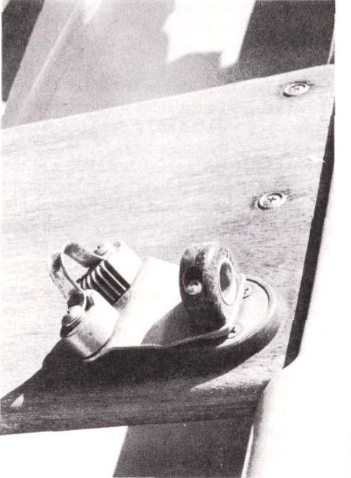

Take a look at the main sheet arrangement. There should be a cam cleat with a ratchet block mounted on a swivel in the center of the boat. The swivel should be strong enough not bend even if you stand on it. Otherwise, the increased main sheet tension caused by a strong puff can bend the swivel’s arm upwards, making it impossible to uncleat the sheet, promising a sure capsize. The main sheet should dead end on the stern, rather than on the boom. Mid boom sheeting is inefficient and causes the boom to bend excessively, especially with a loose-footed main-sail. On a small boat, the vang can be used to hold leech tension as you ease the main in a puff. Therefore a strong vang is far more important than the existence of a mainsheet traveler.

If the boat has hiking straps, check how well they are attached. Grab the strap and try to rip it out of the boat. Hiking straps attached with screws usually tear out. A strap with a grommet in it, tied to the floor with line, is better.

Check the running rigging to make sure it is long enough. The manufacturers of cheap boats often skimp on this.

The tiller should have a tiller extension, and the extension should be long enough so you can hike out. Most tiller extensions are too short. The extension should be attached to the tiller with a universal joint.

Following these guidelines you should be able to get a pretty good idea of a small boat’s quality. Don’t be embarrassed to tug on this and pull on that to ascertain the strength of a small boat. If you don’t want it to fall apart at a later date, it should be able to take everything you give it.

The Trailer-Sailer

There are no boats on the market more common than those between 20 and 25 feet. These are the so-called trailer-sailers, though many are not really trailerable, and none are large enough to be called a cruiser. Trailer-sailers such as the O’Day 22 and 23, the Venture (MacGregor) 25, the Cal 22, the Catalina 22, the Balboa 22, and the like typically weigh from 2 000 to 3 500 pounds. They are shoal draft, usually with a weighted swing keel or centerboard, and most use an outboard motor as auxiliary power.

The Keel Types Comparison and Additional Design Considerations for Sailboatscost of the boats we are talking about seldom exceeds $ 10 000 and they are likely to be available on the used boat market for prices far below that figure. This opportunity to become involved in sailing for a minimal outlay is what makes these boats so appealing. However, big dollars or not, there are factors any buyer should keep closely in mind. Let’s start with some assumptions and presumptions:

Originally boats of this type were built with price being the foremost consideration, designed to compete in the new-boat market against higher priced counterparts. As a result, the quality of the finish and the cruising amenities are not apt to be their best features.

The limitations on size, draft, and cost are likely to affect performance; most trailer-sailers are not lively boats to sail although they can be safe, maneuverable, comfortable, and fun.

The limits on the cockpit size, the number of berths, and the amount of elbow room restrict the number of crew these boats can handle. For anything other than day sailing, they are best suited for a couple or a small family.

Trailering a boat over 2 500 pounds (the total weight of boat, trailer, equipment, outboard motor, etc.) requires a proper car, trailer, and hitch plus some experience with launching, hauling, and driving.

A trailer-sailer is likely to have been owned by a sailor for whom this was a first boat. As a result, the boat may have been neglected or even abused; at best, it probably has not had careful routine maintenance.

Trailer-sailers are customarily sold by the owner rather than a broker, although they are frequently offered through new-boat dealers who have taken them in trade.

Typically, the equipment offered with used boats of this type is limited, but might include such extras as an outboard motor or trailer that can drastically effect the price.

First Considerations. Any buyer in the The Boat Market and Possible Force Majeure Situationsmarket for a boat of this size and type should outline his priorities just as the buyers of larger, more expensive boats would. For instance, if trailering is to be an integral part of cruising with the trailer-sailer, then weight and draft could be more important than sailing performance and livability. Similarly, if obtaining experience and skill in sailing and boat handling are top concerns, then simplicity and easy maintenance move to the top of the list. There is no easy way to set priorities, but fortunately, there is a wide variety of boats in this size and price range to meet a wide variety of needs. The best approach is to list your priorities, then look for a boat to suit them. To start with, decide where you will sail, with whom, and how often.

A few priorities that commonly affect the choice of a boat of this size are listed below with no attempt to rank them by importance:

- Cost.

- Performance.

- Livability (comfort belowdecks).

- Cockpit size and comfort.

- Suitability for racing.

- Shoal draft.

- Light weight (for ease of trailering).

- Stability (the resistance to heeling).

- Seaworthiness (the inherent safety of the boat).

- Builder’s reputation.

- Availability.

- Resale value.

- Ease of maintenance.

- Aesthetics (appearance, finish, etc.).

Of course, each of these priorities can be subdivided. For instance, «livability» might represent the number of berths, a fully appointed galley, an enclosed head, or even some other single feature a buyer regards as crucial. Similarly, performance might be more precisely defined as the ability to sail in heavier winds if those are the typical conditions in the area where the boat will be used most.

What to Look For. Woe to the boat buyer, even one with his priorities straight, who blindly plunges into the marketplace with no idea of what he is looking for in the way of makes or models. This is where the buyer of a new boat has an advantage; he can readily see what is available in boat shows and dealer showrooms. The used-boat buyer has to be more organized, more patient, and more creative in his search, but he will have more choices (far more models of boats are on the used-boat market than are available as new boats), so he is in a better position to find a suitable boat to fit more exacting priorities.

Nevertheless, the search for a boat invariably introduces the matter of compromise. New or used, the «perfect boat» is impossible to find, in large part because priorities tend to change as buyers become more familiar with actual boats. For instance, a top priority may be traditional styling and quality finish, but in the realities of the marketplace such styling is expensive and thus may conflict with another priority, moderate cost.

To search out a good used trailer-sailer takes time and effort to answer ads, and to amble through boatyards and marinas. Since boats of trailerable size are often kept in backyards and garages, the search may not be easy.

When You Find a Possibility. Buyers of large boats wisely hire a surveyor to assess a potential purchase. As the price of a boat falls much below $ 8 000 or so, the economy of a $ 150 to $ 200 survey becomes less justifiable, albeit still worthwhile if the buyer is not sure of his own ability to assess the condition of a boat or its suitability for his needs.

Above all, in looking at a possible purchase, do not be swayed by mere cosmetics – the shine on the topsides, the smoothness of the bottom paint, the pattern of the upholstery. Any smart seller will take pains to create a favorable first impression and will set his price to take advantage of it.

Start by asking for a detailed background on the boat – year built, number of owners, how the boat has been used, what has been done to upgrade the boat, declared insurance value – and ask for a basic inventory of what is included in the sale price. The inventory should include the normal equipment aboard the boat such as:

- working sails;

- ground tackle;

- fenders;

- dock lines;

- USCG-required safety gear, and so forth.

It may or may not include such items as a head, galley facilities, outboard motor and fuel tank, extra sails, trailer, dinghy, or paid-up yard storage bill. Until you have such an inventory, the asking price means little. After all, the difference in price between a «bare» boat and one that is well equipped may be far less than the cost of outfitting the poorly equipped boat.

Source: wikipedia.org

A careful assessment of the boat requires looking closely at the condition of the boat and the equipment included in the sale. In assessing the boat’s condition, start with the mechanical systems. The centerboard (or keel) lifting system is one that needs special examination, as repair may be difficult and expensive. Similarly, the rig deserves close scrutiny, as do molded fiberglass components such as hatches. The most vulnerable moving part of most boats of this size is the rudder. Remember, the boat may no longer be in production, and the builder may no longer be in business, eliminating a source for replacement parts and information.

Assuming the condition of the boat passes muster, the next step is to assess the extras. In general, items such as sails, outboard motors, and trailers have a useful life far shorter than the usual life of the boat itself. With proper care, a fiberglass boat has an indefinite life span; boats built 30 years ago are still hale and hearty. The same cannot be said for sails whose life expectancy with normal use is perhaps seven to ten years. Outboard motors more than three years old have to be suspect; you might find an older motor that is perfectly serviceable at five or six years old, but the chances are slim. It is better to be prepared than surprised if the motor you buy with a boat needs replacement.

The trailer should also be examined carefully. Fortunately the basic condition of a trailer is easy to assess, probably easier than the boat itself. Keep in mind, too, that if trailering is not part of your plans for the boat, a trailer as part of the sale price is a liability. You are paying for an extra you do not need and will have trouble selling by itself.

In evaluating the prospective boat, be armed with information, not only about what sisterships are selling for, but with the price and degree of difficulty of replacing major components or of adding those the boat lacks. These have to be considered with the sale price to get a reasonable approximation of what the boat is worth. Small boats of this type, unlike larger boats, seldom make extensive refurbishing practical or economical. It is a safe guideline that for smaller boats, additional expenses more than 20 percent of the sale price to get sailing are not worthwhile, and the total outlay should never exceed the fair market value of the boat. In our opinion, it is better to pay more for a boat that is in better condition or one that is better equipped.

At the same time, there are many genuine bargains available. Often the owners of boats of this type are anxious to sell. They may be moving up in size, out of sailing, or whatever. What they are selling is a boat for which there is a crowded market and a modest dollar value. They may have less idea what the buyers are paying for sisterships than you do. Cash in hand may be crucial. All these factors are to the advantage of the buyer. Let the satisfaction you have in your new vessel start with favorable negotiations for her purchase.

How to Pay for the Boat You Choose. Our suggestion to prospective buyers is to try to pay cash for boats such as these. Unlike larger, more expensive boats that represent more solid equity, small boats rarely appreciate in value, or cost enough to justify interest or finance charges (banks typically do not regard used boats of this size and value as suitable collateral anyway).

This does not mean that your boat should not be considered an investment. It should; someday its value on the market may be a solid contribution to a down payment on another boat. This is why good maintenance is important. Nevertheless, beware of large capital outlays unless you plan to keep the boat for a reasonable time to amortize the cost. The need for new sails, a new motor, a new trailer, a new mast or boom, or more powerful winches, should all be reasons for a bit of thought, since these items do not appreciably increase the value to the next buyer. Rather than buying the new gear, it may be time to put that money toward the next boat, precipitating the decision to sell. Knowing when to sell is just as important as knowing when and how to buy.

Buying a small boat is an exercise identical to Buying and Selling Making – a Sound Investment In a New or Used Boatbuying a large boat. So too is the effort, and yes, the satisfaction of owning one. The difference is a matter of scale. Because owning any boat should not represent a hardship – financial or otherwise – many sailors would be better off with a 22-footer that costs $ 6 000 than a 30-footer that costs $ 26 000. However, the validity of this assumption is based on its being a good, safe boat that fulfills one’s needs or desires.

Any buyer should know the limitations of a small boat. They are not meant for sailing in unprotected waters and they need a modicum of skill both in handling and maintenance. At the same time, their trailerability gives them versatility that may not be available in a larger boat—hence their appeal.

The Transition Yacht

At what point does a trailer-sailer cease to be a glorified day sailer with minimal accommodations and become a cruising boat with genuine livability? At what size does a boat become a seakindly craft with small boat handling and large boat performance? We ponder this question every time we look over a small boat.

The more boats we look at, the more clearly we perceive a transition point where a boat becomes, if you will, a yacht. For example, although the O’Day 25 is the same length as the MacGregor 25, the O’Day is clearly more of a «yacht» than the MacGregor; she weighs twice as much, she costs twice as much, and in our opinion, she offers the promise of twice the comfort, cruising range, and value.

It is easy enough to identify boats on the ends of this continuum, but there is a range of small cruisers in the middle with a mix of these characteristics. We call them «transition yachts».

Historically, transition boats are a creation of the market-place, developed with evolving technology to meet consumer demand. As the boom in production fiberglass boat building developed during the last 25 years or so, boat buyers indicated they wanted boats with more and more accommodations and better seaworthiness for a modest price. To answer that demand, the waterline became longer, the beam wider, and the topsides higher. At the same time, builders found that fiberglass reduced the amount of hull structure needed for strength. As a result, interior volume increased without commensurate increases in either overall length or displacement.

By the mid-1970s, the most popular boat in the marine market-place became the smallest boat that had the space, amenities, and comfort of a larger yacht. Today they are more popular than ever.

Essentially, these are small cruisers that try to offer the accommodations and performance of larger boats. They tend to have a minimum length of about 25 feet and a displacement of about 4 500 pounds. Some are touted as trailerable, but many, if not most, owners treat them like larger boats and seldom trailer them except perhaps home for off-season storage. Many come in shoal-draft and deep-draft versions, and offer inboard auxiliary power as an option to the Inboard and Outboard Enginesstandard outboard.

In general, their styling and proportions are those of larger boats. They have full accommodations below and an «offshore» type rig rather than a «one-design» type. For amenities, they have a galley with a stove, sink, utensil storage, and built-in icebox; an enclosed head; fixed water tankage; and an electrical system – all normal features found on larger boats.

In addition, an owner with the cash and the inclination can add goodies that larger boats boast as standard:

- spinnaker and gear;

- wheel steering;

- refrigeration;

- a shower;

- a stove with oven, even a pressure water system.

Intrigued with their promise, we set about to define the trade-offs, the compromises, between small size, full accommodations, price and performance inherent in transition cruisers.

The Performance Compromise. To a large degree, maximizing livability and performance is an exercise in contradiction. This is the main reason why boxy, shoal-draft boats with small rigs often sail slowly or handle poorly in a breeze or a seaway. Conversely, high-performance boats are often light and quick, but have only spartan accommodations and cockpit comfort.

To complicate the choice between spacious accommodations and sparkling performance, designing for shoal draft works against both. A shallow keel configuration, with or without a centerboard to alter draft, is less efficient than a deep keel, particularly a high-aspect fin. In addition, to provide comparable stability, the shoal-draft keel must weigh more than a deep keel, increasing displacement and trailering weight.

Don’t forget to consider the aspect of performance under auxiliary power. Clearly a boat 25 feet long and weighing over 3 500 pounds is pushing the limit of capability of an outboard motor mounted on a transom bracket. A 10-horse power out-board, barely adequate for smooth water powering, weighs almost 100 pounds, drinks fuel like a sot guzzles booze, does little to slow a boat of this weight in reverse (let alone permit her to back down), and pulls out of the water with any pitching (to which its weight on the stern contributes). Outboards do have advantages; namely, ease of servicing, and cost. The motor can be carried to a service center and it carries a price tag about 30 percent of that of an inboard installed.

By contrast, inboard engines, notably small diesels, are generally powerful, dependable and efficient. They typically are tucked away under the cockpit in a space that is otherwise likely to be fairly inaccessible. Their fuel is safer and better stored. And a small diesel can produce what should be more than adequate electrical power.

For all that convenience and effectiveness, the inboard engine is costly, perhaps $ 4 000 or more. While it may be hard to justify such a price tag, adding perhaps 20 percent to what might be an affordable base price, the inboard does prove to be a reaonably good investment. Boats with inboard power sell faster as used boats than boats with outboard power, recovering much of the initial outlay. An outboard motor more than three or four years old puts a potential buyer of your boat in an excellent negotiating position.

One alternative seemingly suited to boats of this size is the so-called sail drive – essentially an outboard motor mounted through the hull so that it acts like an inboard. However, we hear many complaints about corrosion in the lower units of these systems, so we think they should be considered only for fresh-water installations.

When looking at a boat where there is a reasonable choice between outboard and inboard power, the buyer must face a compromise between cost and performance; it is not an easy choice to make.

Less a compromise but well worth mentioning is the matter of the safety and seaworthiness of the transition cruiser. There is little question that for a given length, the transition yacht, as a junior version of a larger boat, will be a more seaworthy vessel than a «grown-up» version of a day sailer. The latter may have lighter displacement, retractable ballast, an open cockpit, lower freeboard, and a less versatile rig, all of which makes her less suited to exposed waters than a transition boat of the same overall length.

In contrast, the transition yacht will have a self-draining cockpit, a seat-level bridge deck to prevent water from going below, a companionway that can be secured, cockpit lockers with positive latches, and a lifeline system. Fuel for the auxiliary is in a fixed tank if the engine is an inboard or there is a separate vented locker for a portable outboard tank.

In short, the proper transition yacht has adopted many of the characteristics of safety and seaworthiness that are typical of larger boats. This may not make her suitable for offshore passages, but the transition yacht should offer a much wider cruising range than her smaller, cheaper, lighter counterparts.

Livability. It is truly remarkable how much in the way of accommodations and cockpit space the designers and builders of many of these boats have managed to provide. Routinely there are berths for at least four, often five. The head is fully enclosed. There is a small but fully serviceable galley, room to store plenty of sails, and abundant locker space for clothes, stores and utensils. Cockpit seats may exceed six feet in length; headroom is usually five feet, eight inches or better.

At the same time, the packaging may be more impressive than the product. There may be five full-size berths, but five adults is clearly too many aboard a 25-footer. The cabin table will seat two better than four (let alone five). The water tankage – 10 or 15 gallons – will hardly be enough for overnight with more than three crew members.

Limited, too, is the capacity of clothes lockers, the icebox, and food storage space for a cruise of any duration. Perhaps worst of all, there is simply too little space aboard such a small boat for privacy. In short, the number of berths should not be used for judging crew capacity; in fact, if cruising with more than three (four, if the crew includes young children) the additional berths may be a waste of valuable space.

Read also: Choosing the Right Boat – Your Ultimate Guide to Selecting the Ideal Vessel

In that space, designers and builders could make forward V-berths that do not disappear into a point where feet are supposed to fit; the galley could have some usable counterspace; the icebox could be made larger. There might be room for clothes lockers rather than the all-too-prevalent scuttles that open into the bilge under the berth.

Source: wikipedia.org

A Few Things to Look For. It is, of course, difficult to delineate what boat will best suit any sailor, but there are guidelines worth keeping in mind when considering boats of this size and type.

Define as well as possible her intended use. If primarily for day sailing, look at cockpit space and performance. If for trailering, consider weight and draft as well as what will be needed to tow the boat and handle her on the launching ramp. If for cruising, set realistic limits on the number of people who will be aboard and the duration of the cruise.

Buy a boat that has a good resale market in your area. For many buyers, this boat will be an interim step before trading up to a larger boat. With this a consideration, the boat they buy should have a resale value (and buyer demand) at least commensurate with the initial investment.

Performance, construction, and seaworthiness are top priorities; decor, cosmetics, and styling are less important. Folding cabin tables look neat but are invariably flimsy. Fiberglass hull liners may look antiseptic compared to wood joiner work but they are rugged and practical.

Choose a boat you can abuse, not one you have to coddle. Boats are meant to be fun, not unrelenting work. This is one of the best aspects of owning a smaller boat.

Don’t buy on impulse or first impressions. Try the berths for size and comfort. Measure the icebox capacity. Feel inside lockers for dryness. Open hatches and ports to check ventilation. If fitted with an inboard, take apart the engine box to see what is required to pull the dipstick. On deck, go through the routine of setting sail and reefing to see how efficient the system is.

Think carefully about options. Dealers place a large markup on fancy electronics, extra sails, wheel steering, and the like; most of these can be fitted at a later date when you will be more familiar with your boat and your needs.

The Bottom Line – Cost. Make no mistake about it; a small yacht can be a large investment. They can cost up to twice what other boats of the same length – the so-called trailer-sailers – cost. In that respect, they demand the same careful consideration any yacht deserves before purchase, new or used. And they require maintenance to protect the investment they represent.

For a couple or small family, the transition yacht offers a great deal for her price. For those on a modest budget and with a modest amount of leisure time, she can be a better value than a larger boat, both because of less initial outlay and because of lower annual upkeep costs.

In addition, many boats of this type are popular on the used boat market, appealing as they do to new, budget-conscious sailors. They are, more than other boats larger and smaller, an asset that should be capable of being turned back into cash fairly quickly if necessary.

Furthermore, these boats are the smallest and cheapest ones that interest marine finance companies. The cost makes a worth-while transaction, the boat represents a solid form of collateral, and ownership entails a firm commitment by the owner.

The bottom line is thus a form of encouragement. On the one hand, the transition yacht can give a sailor the type of sailing enjoyed by the owner of much larger craft at a much more economical cost.

On the other hand, buyers of boats of this size should shop carefully and thoughtfully for the most suitable boat and the best value. There are, however, plenty to choose from – about 60 different models by our latest count.