Yachts Cooking Solutions are essential for any boating enthusiast looking to elevate their culinary experience on the water. Whether you are preparing a simple breakfast or a gourmet dinner, having the right cooking equipment can make all the difference. From compact stoves to versatile refrigeration units, these solutions are designed with space efficiency and functionality in mind. In addition to cooking devices, essential storage equipment plays a crucial role in maintaining organization and freshness onboard. Ice chests, holding plates, and innovative storage systems help you keep your provisions in perfect condition, allowing you to enjoy delicious meals throughout your journey.

By combining advanced Yachts Cooking Solutions with high-quality storage equipment, you can ensure that every meal is not just a necessity but an enjoyable event, transforming your yacht into a fully equipped kitchen that meets all your culinary needs.

Ice Chests

Needs vary widely with regard to food storage and refrigeration. Whether the goal is to keep a six-pack and a picnic lunch cold for a half-day fishing trip or to adequately provision for a crew of 8 to 10 on a two-week offshore cruise, some prepurchase evaluation of the boat’s systems and capacities for storing fresh, frozen, or packaged food will yield genuine benefits.

For small day cruisers, a portable ice chest might be all of the food storage required. An ice chest is inexpensive to acquire, will demand very little maintenance, and uses no electricity. When secured by deck braces, a stoutly built ice chest can additionally justify its space on a small boat by doubling as another seat. Some enterprising manufacturers sell seat cushions designed to be used atop an ice chest. An ice chest is also useful aboard a boat with a small built-in refrigerator, when temporary demands (such as entertaining a larger-than-normal crowd) exceed the regular capacity for cold storage.

Twelve-Volt Refrigerator/Freezer Combos

Boaters who spend quite a bit of time at various city marinas, or whose cruising habits involve being anchored out for no more than a few days, will be sufficiently served by a 12-volt/110-volt refrigerator/freezer unit. These popular coolers operate either from the 12-volt DC power of the onboard batteries, or by converting available 110-volt AC shore power to 12-volt DC and not taxing the house batteries. The most popular sizes of these built-in units are approximately three cubic feet and six cubic feet. When operating from the house batteries, these refrigeration units draw about one amp per cubic foot per hour (and will actively run about 30 minutes per hour). So the operation of a six-cubic-foot refrigerator/freezer for 48 hours can consume the entire 150-amp recommended maximum discharge of a 300-amp battery. If nothing but the refrigerator were drawing down the house battery, it would be smart to start a generator or run the main engine for a period of time sufficient to recharge the battery every couple of days. Cabin lights, water pumps, radios, heater and vent fans, anchor lights, and so forth usually share the power of the same battery running the refrigerator. In most cases when anchored out with 300 amps or less of house-battery capacity and a six-cubic-foot refrigerator/freezer combo, it is advisable to run a generator or main engine for a brief period everyday to replenish the house-battery bank. On a used boat with this type of refrigerator, make sure that the original unit has not been replaced on the cheap with something from an RV supply store. Appliances sold for use in motor homes are not suitable for a boat as they usually are not constructed from material with adequate corrosion resistance.

Ice Is Nice. Refrigerator/freezer combinations are very popular because they are similar in concept and appearance to home refrigerators. Other than their fairly inefficient use of power, the only serious compromise with these appliances is the paltry freezer capacity, particularly on the smaller sizes. Boaters who entertain a lot and operate an active bar would have a difficult time counting on the combo refrigerator/freezer to provide a reliable quantity of ice. A number of manufacturers build 110-volt AC icemakers which are handy when dockside (or when the generator is running) for keeping the drinks cool or creating a chestful of ice to store the catch of the day until dinner time.

Source: wikipedia.org

Iceboxes and Holding Plates

Built-in iceboxes are found on some older boats and on boats where the accommodations for passengers and crew are extensive enough that a typical refrigerator would not be sufficient to keep a logical amount of food cold. Iceboxes are seldom cooled with ice. Very high efficiency Inspecting the Primary Systems – A Comprehensive Approach to Marine Maintenance and Performance on Yachtscooling systems known as holding plates can, in a well-insulated ice box, create temperatures as low as – 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

A holding plate’s compressor may be powered electrically and/or driven hydraulically by the boat’s engine. Seawater can be pumped through the cooling machinery to more effectively transfer the heat, but many simply transfer the heat removed from the icebox into the bilge, cabin, or out-side air. Engine-driven systems may need to be operated for only an hour or two per day to maintain adequate refrigeration.

Other Refrigeration Options. Larger boats with all-electric galleys and onboard generators often have a standard household-sized refrigerator that operates on AC only. On boats with propane, there are some thermoelectric refrigeration systems which are propane driven. Many of these systems are a three-way affair, combining the possibility of propane-generated power with the options of 12-volt battery or 110-volt AC operation.

The Freon Question

To prepare yourself for an eventual expense or to discover that there is one less thing to be concerned about, determine if possible what type of refrigerant gas is used aboard. For decades the standard refrigerant gas was R-12, but due to concerns that R-12 (freon) is a major contributor to the reduction of ozone in the earth’s upper atmosphere, the manufacture of R-12 has been, by law, discontinued in most countries in the 1990s. Refrigerators using R-12 are still legal to own and operate, but when being serviced a technician must take special precautions to capture any freon which might need to be vented from the system. The captured refrigerant is then processed, filtered, and recycled into other refrigerators which need a recharge of coolant. Since freon is no longer manufactured and some R-12 will inevitably escape into the atmosphere through leaky fittings and so forth, the supply of R-12 is disappearing faster than the refrigerators which require it are wearing out. So, freon is scarce and expensive. Many systems originally designed for R-12 can be fairly inexpensively converted to utilize one of the more modern, alternative gases available. New boats, or boats where the refrigeration has been upgraded since 1996, ordinarily use a refrigerant such as HFC-134A which does an excellent job of absorbing heat and at least so far has not been found to have any damaging effects on the atmosphere.

Canned, packaged and freeze-dried storage. The galley lockers on most boats require the cruising chef to rely on a basic selection of cooking utensils. To accommodate sufficient storage for canned and packaged foods in a fairly compact area, many of the specialized pans and appliances taken for granted in the kitchen ashore need to be replaced by a few highly versatile items. If there just doesn’t seem to be enough storage space in the galley, there are probably a number of places aboard where canned, packaged or freeze-dried foods can be stored for extended periods, to be brought to the galley every few days.

Galley Stoves and Fuel Systems

Cooking Properly and Safely Storing Food on a Boatappliances on boats are most commonly fueled by alcohol or propane, or use electricity, Cooking units in the marine environment will quite often feature stainless rails around the perimeter of the cook top or some other system to keep pots of boiling water from sliding off in a beam sea or when the boat encounters a large wake.

Alcohol Stoves

Small boats commonly use a two- or three-burner alcohol stove, with liquid alcohol being stored in a reservoir and used to create controlled flames for heat. With any type of open-flame system, owners of gasoline-powered boats must be especially cautious that there is no buildup of gasoline vapors in the bilge while the stove is in operation. Most boats with alcohol stoves are under 28 feet and properly designed to provide an adequate ventilation for safe operation of an alcohol stove.

Electric galley ranges. Larger boats with onboard generators often use a three- or four-burner electric cook top and oven combination. These marine versions of an electric range operate on 110-volt AC power at sea, and some may also adapt to 220-volt AC when connected to an ample supply of dockside power. A generator producing ample AC current is required to operate an electric galley range when anchored or underway.

Diesel cookstoves. Diesel cookstoves are not unknown, but while somewhat commonplace on tugs or commercial fishing boats, their use is pretty unusual on pleasure boats, A diesel stove uses a flame to heat an iron stove-plate and the exhaust is piped directly out of the boat.

Propane Stoves and Systems

On many boats, galley stoves are fueled by propane (Liquefied Petroleum Gas). Space heaters, deck-rail barbecues, and thermoelectric refrigerators may be powered by propane as well.

Safety Concerns. Propane is a flammable gas which is heavier than air. Any propane which enters a boat (and is not burned) gravitates into the bilge. When properly installed, maintained, and operated, propane systems are of no particular safety concern on most boats, but some prudent mariners resist the use of propane stoves on gasoline-powered boats. Gasoline vapors can conceivably be ignited by the open flame of a propane burner or oven unit, and propane vapors collecting in the bilge can create an explosive condition if ignited by stray current from an engine’s electrical ignition system.

Propane lockers. Propane tanks should be mounted in a dedicated locker on the exterior of the boat. Some boats have propane tanks secured directly to the deck or superstructure without benefit of a container to protect the tanks and valve assemblies from the elements or the possibility of damage from accidental impact. Propane lockers should open directly to open air, and not be located below decks, in a lazarette, or other enclosed area. Propane lockers should be vented from the bottom (remember heavier than air), with the vent line running overboard to a point above the waterline but no closer than a couple of feet from any engine, stove, or furnace exhaust ports.

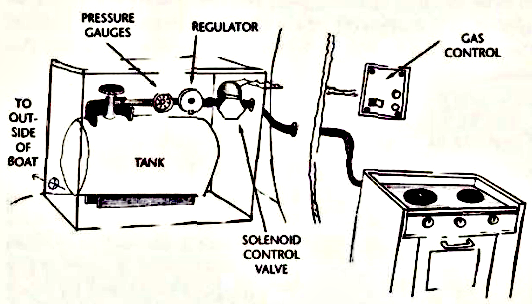

Valves and Solenoids. All propane systems need a shut-off solenoid in the locker to allow the flow of gas to be stopped remotely from the galley by means of an electric switch. It isn’t always practical to close or open the main propane tank valves each time an appliance is turned off or on, but most boaters will shut off the manual tank valves when securing the vessel for the night.

Read also: Cruising in Comfort on a Sailboat

Propane Lines. On a used boat, it can be important to be sure that there have not been any post-manufacture splices made in the propane fuel lines. Each propane appliance should have an individual, unbroken fuel line running directly to it from the propane locker. T-fittings are acceptable as part of the plumbing assembly exiting the propane tanks, but no other joints should be made «downstream» from this point. Most manufacturers would never consider running a propane line through the bilge or engine room, and it might be wise to determine that a former owner hasn’t routed a line through these areas during a previous renovation.

Sniffers. Every boat with propane aboard should have a gas-detecting sniffer installed in the bilge. The sniffer should be connected to a loud audio alarm and may also connect to the electric solenoid control in the propane locker. Most sniffers will have a test position so that a boater can determine that the sniffer is operational and be familiar with the sound of the sniffer’s alarm.