Marine Systems Overview highlights the critical elements that ensure the safe and efficient operation of vessels. This includes propulsion systems, fuel management, and electrical configurations, all of which play vital roles in a boat’s performance. Understanding these components is essential for regular maintenance and troubleshooting. Moreover, an awareness of the various technologies involved, such as inverters and generators, can enhance energy efficiency onboard.

- The Limitations of Advertising

- The Preliminary Survey

- The Benefit of Vocabulary

- Start with the «Heart»

- The Engine Room

- Visually Examining the Engine

- Oil Analysis and Engine Surveys

- Drive Lines, Propulsion, and Holes in the Hull

- Stern Tubes, Cutless Bearings, Stuffing Boxes

- Inboard/Outboard Systems

- Thru-Hull Fittings and Seacocks

- Bilge Pumps

- Bigle Pump Capacities

- Fuel Systems

- Vents, Valves, and Deck Fittings

- Fuel Capacity and Range

- Fuel Aging and Stability

- Water Separation and Fuel Filtering

- Fuel Lines

- Cooling and Exhaust Systems

- Raw-Water Cooling

- Manifold Cooling and Muffling

- Raw-Water Strainers

- Waters Pumps

- Exhaust Systems

- Electrical Systems

- The Battery System

- Distribution Panels

- Wire

- Inverters and Generators

- Electrolysis and Corrosion

Proper fuel management and filtration systems are crucial for preventing operational issues, while effective cooling and exhaust systems ensure environmental safety. By familiarizing yourself with these aspects, you can contribute to the longevity and reliability of marine vessels.

The Limitations of Advertising

Most privately placed ads and a large portion of brokerage ads contain little useful information or tend to emphasize fluff over function – not surprising when one considers that the function of the ad isn’t to sell the boat but to generate phone calls and allow the seller to make appointments with potential prospects. It should be surprising either that many people shopping for their first powerboat suffer from advertising-induced confusion regarding what aspects of a vessel are of greatest importance. Even when attempting to carefully inspect a boat, first-time buyers can have little understanding of what they’re actually looking at. Items or conditions which are important get overlooked or ignored.

The Preliminary Survey

Used boats are ordinarily bought and sold subject to inspection by an independent surveyor. Every boat buyer should insist on a survey when making an offer, especially when purchasing a used boat. Lending institutions will require a survey in order to substantiate value when calculating the maximum loan available on a previously owned vessel. Surveys have even been performed on new boats, turning up such things as wires that have been misrouted, installed items not properly secured, parts installed that are less than spec. No inspection by a boat buyer will ever substitute for a good survey. But since the costs of hauling the boat out of the water and hiring the surveyor (two items that get up into the hundreds of dollars very quickly) are traditionally borne by the prospective purchaser, discovering conditions which are serious problems or shortcomings in a boat prior to making an «offer subject to survey» can save a good deal of time and frustration as well as cash. The surveyor can render an expert opinion regarding the condition of the hull and the equipment but will be operating under the assumption that the buyer has reached an independent conclusion that the boat, if sound, is suitable in the first place.

The Benefit of Vocabulary

Many items found aboard a boat and much of the vocabulary used to describe them are unique to boating. More than a few novice boaters have nodded as if completely understanding while listening to a discourse that might as well have been «the flibbity gibbet has been moved aft to accommodate a larger hockum snocker, and the framus has been refitted with a fresh diogenator upgraded to mofligander standards». Two of the traditional difficulties when trying to communicate on any technical subject is the assumption of one party that «everybody knows what I’m talking about», and the reluctance of another party to appear underinformed which may prevent him from stating, «Could you repeat it in layman’s terms?» Becoming familiar with some of the major systems aboard a powerboat will be of immeasurable assistance in conducting informative discussions with a seller.

Start with the «Heart»

If you were to visit a doctor to have your health your health assessed and the doctor spent most of the appointment examining toe nails and eyelashes, it might be difficult to develop a strict confidence in the comprehensiveness of the exam. You might ask, «Doc, how about my heart? It’s the single organ that will kill me quick if it stops working!» Boat shoppers often act like the absent minded physician described above. It isn’t unusual for prospective buyers to concentrate on the upholstery, the electronics, the appliances in the galley, and whether or not there’s a tub in the head, while completely forgetting to examine the engine room where the «heart» of any powerboat is contained.

While there’s very little point in thoroughly examining a prospective acquisition if it is somehow unsuitable, once an initially favorable impression is established, it becomes appropriate to begin a hard scrutiny of the nuts and bolts of a vessel. It is of course impossible to determine how well a boat will run by visual inspection alone, but certain things seen or not seen in the engine room can give some indications of what to expect. The engine room contains the largest concentration of equipment on a boat, much of which can be almost prohibitively costly to replace. How well it all works will not really be evident until sea trial, and sea trial won’t occur in most instances until there’s a conditional offer and deposit. A boat buyer must initially rely on what he sees to draw preliminary conclusions about the mechanical condition of a vessel.

The Engine Room

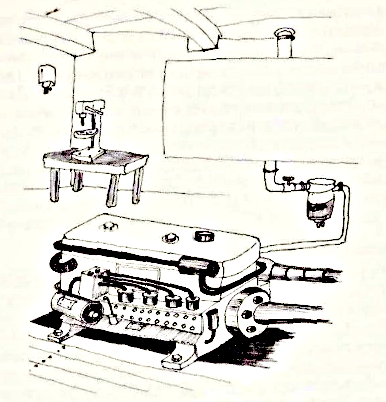

Access to the engine room is typically down through the rear deck on boats with a cockpit, or through the cabin sole on boats with engines mounted more amidships. On larger vessels, some owners enjoy the luxury of walk-in engine rooms with ample space for servicing the machinery, and perhaps even tool-storage lockers and a workbench. Unless you plan to hire out all of the mechanical work, you have to envision a few afternoons each year (possibly on hands and knees) changing oil, filters, zincs, and other routine tasks. Accessibility is an important consideration. On twin-engine installations, some builders have configured the engine assemblies to maximize ease of access to dipsticks, filters, etc., while others have not.

Lighting. Adequate light in the engine room is a necessity. The lack of it will require the dexterity to juggle a flashlight as well as a wrench or a screwdriver at the same time. A 120-volt light system to back up the 12-volt fixtures is a desirable luxury, as most routine maintenance will occur when the boat is docked and connected to shore power. While it can be difficult on medium-sized and smaller boats to keep even industrial light bulbs from vibrating themselves into a useless state, one or two 120-volt outlets into which a boater can connect a portable «trouble light» will serve as well as a permanent fixture.

The portability of the unit will allow light to be concentrated on particular portions of an engine undergoing adjustment or repair. There is some wisdom in bringing a small flashlight along during the initial examination of a powerboat, and rubber kneepads are found aboard many vessels without room to stand in the engine room, for reasons which can quickly become painfully apparent to boaters who haven’t acquired the kneepads yet.

Ventilation. Gasoline-powered boats should, by virtue of their design alone, have exceptionally good engine-room ventilation with power-driven blowers to eliminate the possibility of explosive accumulations of vapors. Ventilation is also very important on diesel boats, since no engine runs well if starved for air, but on a diesel boat ventilation of the engine room and bilge areas does not need to be fan forced. Engine-room ventilation will remove the acidic fumes that are produced when wet-cell batteries recharge, and it is considered universally desirable to keep as much engine smell out of the interior as possible. Adequate ventilation can help make the engine room a cooler and fresher working environment on hot summer afternoons.

Sound considerations. If a boat has had sound insulation installed, it will be visible in the engine room, on the walls and ceiling, which is of course the underside of the deck or cabin sole above. Look for a layer of material ordinarily 3/8 or thicker which is resilient to the touch and will absorb engine noises. Some boats use a sound insulation which looks more like acoustic ceiling tile. Sound insulation will enhance any power boat – when can you remember a complaint about a boat being too quiet? – but many have been constructed with either an inadequate amount or none. Should you find a boat without adequate sound insulation it might be advisable to carefully scrutinize whether other shortcuts have been taken. Boats built with bulkheads close enough forward and aft of the engine(s) to contain engine noise in a smaller space operate more quietly than vessels where the engine noise can spread unchecked through a more open area below decks.

«Oily» warning. Engine-room surfaces should not be greasy or oily unless there’s a problem with the engine, such as bad crankcase ventilation, or a lot of sloppy mechanical work has occurred there. Either scenario could be cause for some concern, A marine engine and transmission should ordinarily be much cleaner than the engines found under the hoods of most automobiles. Auto engines can become dirty from splashing through mud puddles and the constant exposure to general road scum, but no such problems exist on a boat. Any oil or grease accumulating on the exterior of a marine engine has either been spilled there when adding fluids to the machinery or has leaked through a gasket or seal. There must be no trace of fuel residue around the fuel lines, fuel pump, carburetor, or fuel injectors. Locations which appear dry but have collected a lot of dirt may have leaked in the past.

Looking for spares. An excellent clue to the maintenance habits of a boat’s current owner is the presence or absence of spares in the engine room. Mechanically conscientious skippers will always have a case of engine oil, a spare oil filter or two, a spare drive belt, a grease gun, a couple of spare fuel filters, minor tune-up parts and spark plugs (for gas engines), a few pencil zincs, and so forth stowed somewhere aboard, most often in the engine room. If these items are aboard, it is more than likely because the present owner is mechanically astute enough to consider them important.

Visually Examining the Engine

Oil and fluids. If you thought to bring a paper towel or a rag (and only with the permission of the present owner or broker), a quick pull of the engine and gearbox dipsticks on a used boat can speak volumes to the knowledgeable shopper. Dirty, black, gritty oil in an engine is a problem from two aspects. The first is that it has been allowed to get into a deplorable condition in the first place, and the second is that the present owner is blasé enough about the situation to The Boat Market and Possible Force Majeure Situationsmarket the boat in that state without regard for the importance of clean oil. If the boat is using multi-weight detergent oil, it will get dark very quickly after an oil change but should not be tar-like or gritty. In most engines where regular oil changes have been performed, straight SAE 30- or 40-weight oil should remain fairly transparent on the stick for 20 to 30 operating hours after an oil change. It can be determined what type of oil is being used in an engine if there are a few unopened containers aboard. While the science behind the practice is often debated, many experienced boaters are reluctant to switch the brand of oil being used in an engine. Some convincing arguments have been advanced against switching back and forth between single-viscosity and the high-detergent multi-viscosity oils. A prudent practice is to follow the engine manufacturer’s recommendation regarding the type and viscosity of oil.

Marine transmission fluid should never smell burnt, appear foamy, or be anything but a very transparent, though probably pink- or red-colored liquid. Obviously, both the engine and transmission dipsticks should indicate proper fluid levels.

On a boat with a closed cooling system, there should be no rust or oily appearance to the coolant in the heat exchanger’s expansion tank. This can be inspected by removing (on a cold engine) the radiator cap on the tank.

Dirty bilge water. Check the bilge. Is the water black and oily? Does it smell like diesel or gasoline? There should never be any gasoline or diesel in the bilge unless there’s a leaky fuel system. Gasoline in the bilge can create an explosive situation. A boat with that condition should not be started until the gasoline is removed legally and the boat well ventilated. Is there an oil-absorbing device in the bilge that is saturated with petro-chemical residue? Bilge water gets dirty only after it comes aboard the boat. Rare is the bilge where a tiny quantity of petroleum has never been accidentally spilled during the routine tasks of changing an oil or fuel filter, but a lot of fuel or oil grime in the bilge indicates a present or previous engine leak.

Drip pans. The drip pans under the engines should have little or no oil in them. A drop or two that missed the funnel into the valve-cover cap at the last oil change or top-off could run down the block and wind up in the pan. But any large quantity of oil is most likely the result of a bad oil-pan gasket or, worse, leaky crankshaft seals.

Rubber parts. Marine engines use a fair number of hoses and rubber elbows connecting the piping that distributes cooling water to the heat exchanger, engine oil cooler, etc. Many of these shaped rubber parts are only available from the original engine manufacturer. With some of these specialized two-inch pieces of rubber priced non-competitively for as much as $ 60 and more apiece, the condition of these rubber parts on an older boat tells a tale about the maintenance attitudes of the previous owner (s). Rubber hoses, belts, and elbows should not be allowed to develop any cracking or flaking before they are replaced. Rubber hoses through which hot water is running always seem to require replacement before their cold-water counterparts.

Oil Analysis and Engine Surveys

When what appears to be the right boat is identified and the sale progresses to the point where a surveyor is aboard, it is common to request that the surveyor extract a sample of oil from the engine crankcase and submit it to an oil-analysis lab. Fees for this test can be as low as $ 20. By having the engine oil scientifically examined and having the types and amounts of various metal and chemical substances measured, a used-boat buyer can be alerted to problems which would not otherwise be discovered without dismantling the engines. The expenses for oil analysis and engine survey are the responsibility of the prospective buyer. When an offer is made, a buyer will want to be sure to state that the offer is «subject to satisfactory hull and mechanical surveys».

Drive Lines, Propulsion, and Holes in the Hull

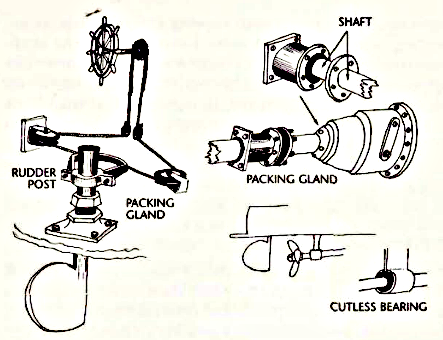

Prop shafts. Most boats larger than trailerable ski boats and day cruisers have inboard engines. Power is transmitted from the gearbox at the aft end of an inboard marine engine to the prop shaft which drives the propeller. As the engine is contained in the hull of the boat and the prop isn’t, it becomes necessary to create a hole in the hull for the shaft to pass through. A system of sealing the hole to prevent the introduction of excessive water into the hull is required. The components and condition of this system are important.

Prop shafts can be as simple as a straight, stainless steel shaft from one to three inches in diameter, or as complex as flexible-drive systems with one or more universal joints. Some fairly unique flexible-drive systems have evolved to reduce vibration transmitted up the shaft from the propeller, or to compensate for engines so positioned in the bilge that a straight drive shaft would not produce a desirable angle of relationship between the prop and the hull. A V-drive system often found on boats where engines are mounted just inboard of the transom is an example of a complex drive system. Prop shafts should not be corroded, cracked, or pitted.

Torque shears and shaft brushes. Some drive lines incorporate non-metallic couplers to connect the prop shaft to the output shaft of the transmission. This coupling disc is designed to sacrifice itself if the prop strikes a log or rock, and helps protects against torque damage to the transmission that might result if the controls were accidentally shifted from forward to reverse at high rpm. Non-metallic shaft couplers also assist in isolating the engine from stray low-voltage electrical currents which could travel up the prop shaft and increase corrosion. A thoughtful addition on any boat is the use of a shaft brush, a light piece of narrow copper sheeting or a stainless strap with copper contacts laid across the top of the rotating shaft and connected to the boat’s grounding system.

Stern Tubes, Cutless Bearings, Stuffing Boxes

The prop shaft passes through the hull via an orifice known as a stern tube or shaft log. To allow the shaft to turn in the stern tube, a tiny amount of clearance is required, thus creating an opportunity for water to come aboard the boat.

Cutless bearings. At the outboard end of the stern tube, the prop shaft is supported by a cutless bearing. Cutless bearings literally require some water to seep between the shaft and the bearing to act as a lubricant when the shaft turns. It is not possible to inspect the cutless bearing until a boat is hauled out for survey, and at that time the surveyor will check for excessive shaft motion at the bearing.

Stuffing boxes. At the inboard end of the stern tube, a stuffing box containing flexible packing material (such as Teflon-impregnated flax) prevents most of the water traveling up the shaft from entering the bilge. Like the cutless bearing, the stuffing box is actually water lubricated, and when properly adjusted, a slow dripping occurs from the stuffing box into the bilge. On boats where the prop shaft turns very rapidly, stuffing boxes often have a fitting by which additional water can be injected into the unit to assure adequate lubrication. Excessive dripping can be reduced by tightening the packing nut, causing the materials in the stuffing box to compress more tightly around the shaft. Some boats feature high-tech shaft seals with a bellows-like apparatus and synthetic gasket materials (often lubricated with hydraulic fluids). It is claimed that these shaft seals can actually eliminate water dripping into the bilge from a prop shaft, and like most boating items, these high-tech shaft seals seem to have attracted both devout fans and ardent critics.

Rudder posts. For each prop shaft there is also a rudder post, a vertical shaft penetrating the hull by which the steering mechanism connects to the rudder blade and controls the rudder angle. Each rudder post has a seal or packing system as well.

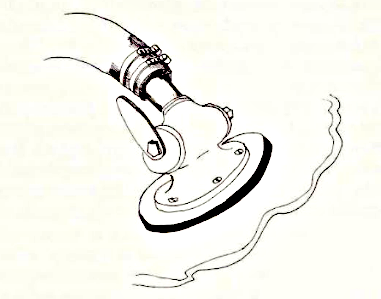

Inboard/Outboard Systems

Smaller craft often incorporate a drive system known as I/O or inboard/outboard. Unlike a true outboard motor where the steering is controlled by adjusting the horizontal angle of the entire engine assembly relative to the stern of a boat, an I/O configuration allows a usually larger engine to be mounted in a fixed position inboard. Steering is controlled by changing the horizontal angle of adjustable transmission and propeller systems known as outdrives. A large rubber boot seals the rather sizable hole in the stern where the outdrive protrudes, and this boot must be in sound condition for the boat to remain watertight. Outdrives are higher maintenance than a fixed propeller, where the steering is controlled by a rudder. During the survey of any boat with an outdrive, seek an expert opinion on the unit’s condition from a marine technician certified by the outdrive manufacturer.

Thru-Hull Fittings and Seacocks

Another important consideration below decks is the system of thru-hull fittings and seacocks. In addition to stern tubes, Choosing the Right Boat – Your Ultimate Guide to Selecting the Ideal Vesselrudder posts, etc., a boat will have several other «holes in the hull», some located below the waterline. Each engine usually has a raw-water intake port through which cooling water is allowed to enter the boat, directed by means of a filter and a hose to the engine. There will be one or more discharge ports for bilge water, one or more inch and a half openings for sewage discharge, and discharge ports for «gray water» from sinks and showers. Rubber hoses connect each of the thru-hull fittings to the engine, bilge pump, or plumbing system as the case may be. As per the theory that a chain is no stronger than its weakest link, even the stoutest hull afloat depends on the integrity of the rubber hoses connected to thru-hull fittings to keep water from entering the hull at a disastrous rate. As rubber hoses may break or leak and require occasional replacement, a valve known as a seacock will be fitted to each thru-hull to close the intake or discharge port in the event of an emergency or when changing a hose.

Seacock maintenance. Hoses connected to seacocks should be double clamped at both ends for an extra margin of safety. Some seacocks are made of plastic materials (and there are undoubtedly some who might claim advantages for the plastic above and beyond lowest possible cost). But the closer any boat approaches to becoming a «yacht», the more likely the thru-hull fittings and seacocks will be bronze. Prudent boaters lubricate all of the seacocks twice a year and test them for proper operation. On a used boat you might see round, tapered, wooden plugs fastened by a line to each thru-hull, indicating the previous owner has prepared dealing with the emergency of a hose failure combined with a seacock stuck in the open position. When inspecting a boat under serious consideration, ask the owner or broker to operate a few of the seacocks to evaluate whether they are working properly. Frozen seacocks can often be dismantled, cleaned, lubricated, and returned to service, but for sea-cocks at or below the waterline this can only be done with the boat hauled out.

A boater was once heard to remark that he didn’t bother to service his thru-hull fittings since most of them were above the waterline. A second boater replied, «How long would they be above the waterline if you began to sink?» The first boater spent the rest of the afternoon freeing up and greasing the seacocks.

Bilge Pumps

Number of pumps. While in the engine room area, use this opportunity to inspect for adequate bilge pumps. As with most systems on a boat, redundancy is very desirable in bilge pumps. One electric and one manual pump are a bare minimum. Either pump should be able to remove water at a rate sufficient to maintain flotation in all but the most disastrous circumstances. A second 12-volt pump is not extravagant, and for boats which will spend most of the time at the dock connected to shore power (possibly without inspection for up to several days at a time), a high-capacity AC pump will assist in keeping a boat afloat in the event that the 12-volt pumps burn out or the batteries become exhausted. In the event of serious flooding underway, the boat’s engines can actually assist in pumping the bilges if a boater closes the seacocks for raw cooling-water intake, disconnects the intake hose from the thru-hull, and draws the engine cooling water from the bilge instead. No boat should rely on a single bilge pump. Bilge pumps on most pleasure craft are too few and of too-small a capacity to adequately evacuate bilge water in the event of a serious hull breach. But they can assist in remaining afloat while emergency repairs are made – i. e., a seacock closed or a piece of canvas or plastic secured across the out-side of a ruptured hull) – or at the very least slow the rate of sinkage, buying time for rescue or evacuation.

Bigle Pump Capacities

The failure of a hose attached to a one-inch thru-hull fitting a couple of feet below the waterline will bring water aboard a vessel at about 28 gallons a minute (1 680 gallons/hour). The rated capacity of any bilge pump is subject to reduction if you have to pump water either higher or farther than the standard under which the pump has been tested. So a bilge pump rated at anything less than 2 000 gallons per hour will have a difficult time keeping the boat afloat. A small boat does not call for a small bilge pump; in fact the reverse is true. While a medium-sized boat might remain afloat with a few thousand pounds of water in the bilge, a small runabout or day cruiser would often have settled to the bottom with far less. It is even more critical that the small boat’s bilge pump keep pace with incoming water. Water comes aboard through a given-sized hull breach very democratically, with absolutely no handicap awarded to various sizes of boats.

Discharge ports. Well-plumbed bilge pumps will pump bilge water overboard above the waterline. Some boats are designed with discharge ports for bilge water at or below the waterline, in which case there must be a loop in the discharge line to prevent water from entering the bilge through the very hose intended to remove it. The loop and longer hose length reduce significantly a bilge pump’s efficiency in the gallons per hour claimed by the manufacturer.

Switches. A well-designed system will have both manual and automatic switches for each electric pump. The automatic or float switches are placed in the bottom of the bilge and activate a pump when the water level reaches a predetermined depth (usually about two and a half or three inches) and shut it off when the water drops to a level of less than an inch or so, The simplest of these switches feature a hinged, hollow plastic arm which floats into a horizontal position as bilge water accumulates. These switches contain a large globule of mercury which flows back and forth as the arm’s angle changes and through which electrical contact is made. (A point to note in the event that a float switch ever becomes physically broken and must be handled: mercury is dangerously toxic). The more deluxe float switches often incorporate such features as a sensor to shut off the pump if oil is being pumped overboard, and guards or screens to protect the float from becoming jammed in the «on» position by a bit of stray debris floating in the bilge.

Manual switches allow a boater to turn on a bilge pump in spite of a malfunctioning float switch or to drain the bilge more completely than an automatic switch might. In days of greater environmental apathy it was common for boaters to routinely pump the entire contents of their bilge overboard at frequent intervals (often waste-water holding tanks as well), and the manual switch was used for this purpose. More enlightened boaters today confine the pumping of the bilge while underway to the frequency dictated by the float switches and will await an opportunity at a sewage pump-out facility to suck the bilge completely dry.

Fortunately, most pleasure boaters will never face a situation where the Safety Equipment for Safeguarding Life at Seabilge pumps are all that maintains flotation, but every boater must be mentally prepared and adequately equipped for just such an event.

Fuel Systems

If the engine is the heart of a powerboat, the fuel is the blood. While in the engine room (aren’t you glad you came down here?), you usually have the best opportunity to visually evaluate the fuel system of a boat.

Fuel tanks. Because of the weight of fuel (350 gallons weighs well over a ton), the location of fuel tanks on a vessel is an important element of initial design. Commonly, fuel is stored in equal quantities and drawn simultaneously from separate port and starboard tanks, or in some smaller boats from a single tank centered in the bilge area.

Fuel tanks typically are made of aluminum, but on many older boats they are constructed of black iron, Iron fuel tanks present the risk of failure through corrosion. Older aluminum tanks will fail on rare occasions as well, typically as the result of inadequate welding or the use of an improper alloy by the manufacturer. When a fuel tank fails aboard a boat, the loss of a few hundred dollars worth of fuel will be the least of a skipper’s worries. Any fuel leaked into the bilge may be pumped overboard by the bilge pump (in the absence of smart switches which will shut the pump off when high concentrations of gas or oil are detected in the bilge water). Any oil pumped overboard must, by law, be reported to the Coast Guard. The discharged fuel becomes the boater’s responsibility to contain and clean up, and failure to adequately clean up spilled fuel or oil can result in a fine of up to $ 20 000. While the cost of purchasing a replacement tank may be hundreds of dollars, the cost of dismantling and reassembling enough of the boat to allow the new tank to be installed will frequently be thousands.

Plastic fuel tanks. On some newer boats, plastic fuel tanks are becoming common. Some experts opine that plastic tanks are superior to aluminum because there is no opportunity for the welds to fail or for any metal disintegration whatsoever. Plastic has no tendency to rust or corrode, is lighter in weight and less costly to produce. Plastic tanks can be custom molded to fit into many of the irregularly shaped spaces on a boat and could conceivably allow more elbow space in the engine room. Someday we may all be boating with plastic fuel tanks, but then again we may not.

Vents, Valves, and Deck Fittings

All fuel tanks must be vented so that air can escape as it is displaced by incoming fuel. A metal fuel tank must be grounded. Tanks should have valves at the point where the fuel supply line to the engine connects so that fuel can be shut off in the event of downstream leakage or when servicing fuel filters. Fuel will normally be pumped aboard through a separate deck fitting for each fuel tank. When back on deck, it will be interesting to note whether the deck fit- tings are labeled or not. Sometimes deck fittings for totally different systems are located side by side and the lack of a label cast into the base of the fitting can be confusing. A veteran boater of my acquaintance once pumped a hundred gallons of gasoline into the freshwater tank of his boat early one foggy morning through an unlabeled freshwater deck fitting located inches away from the also unlabeled fuel deck fitting. Some labels are on the threaded cap of the fitting itself. In such a case it is very helpful if the deck fittings are of differing diameters to prevent the accidental replacement of a labeled cap into an improper opening!

Fuel Capacity and Range

Fuel capacity will help determine the adaptability of a boat for certain types of cruising. Boaters who venture into remote areas may find it necessary to plan a cruise from fuel dock to fuel dock – where they will have to pay what-ever price is being asked – if they burn dozens of gallons of fuel per hour and only have a few hundred gallons ofcapacity. Some boaters can cruise all season on 300 gallons, while others will use that much in a three-day weekend. For boaters planning extended offshore cruises the range of a vessel becomes important.

Range is calculated by dividing fuel capacity by gallons per hour consumed times cruising speed. A boat which travels at 12 knots while burning 9 gallons of fuel per hour would have a range of 396 nautical miles if she carries 300 gallons of fuel. A boat which cruises at 25 knots while burning 40 gallons per hour would need 600 gallons of fuel capacity to achieve a range of 375 nautical miles, while an 8-knot vessel with 300 gallons of fuel burning at 2 1/2 gallons per hour has a range of almost 1 000 nautical miles. A practical skipper will try to refuel before exhausting more than three quarters of the fuel supply, so the effective practical range of a boat is actually only about 75 percent of the theoretical range established by the fuel capacity.

Fuel Aging and Stability

Too much fuel aboard can have drawbacks as well, making a boat unnecessarily heavy and allowing the fuel to become so old that it destabilizes. Gasoline allowed to sit for an extended period will lose some of its more volatile components through evaporation, resulting in greater difficulty when starting a cold engine. Diesel fuel in particular can become a little quirky when allowed to age for too long, from both destabilization of the original fuel chemistry as well as a tendency to foster the growth of a filter-clogging «fuel fungus». Various miracle goops and additives are sold to prevent destabilization of fuels and to kill off diesel scum bugs, but keeping a fresh rotation of fuel through the tanks is the recommended method of prevention. Keeping fuel tanks fairly full will reduce the amount of water forming from condensation on the inside of a partially emptied tank, so the temptation to purchase less than a tankful should be avoided, even at the risk of possibly having to deal with an overaged fuel supply.

Conscientious boaters try to purchase fuel from established, high-volume suppliers whenever possible to help assure a fresh and fairly contamination-free fill-up. Many boaters who must fuel up outside of the US or Canada carry Baja filters, large funnel-like devices placed at the fuel intake port while filling up, and intended to trap much of the water, rust, and dirt which often contaminates fuel in less-developed countries.

Water Separation and Fuel Filtering

The old cliché states that «oil and water do not mix», but they will certainly make one heck of an effort to do so in the fuel systems of most boats. Some water may be pumped into the fuel tanks at the fuel dock, and some may form as a result of condensation. Warm fuel being pumped back into a cool fuel tank from the return line of a diesel injection pump will accelerate condensation, As water accumulates it settles to the bottom of the fuel tank and is drawn off through the fuel line. Between the fuel tank and the engine on most boats is a filtering system which incorporates a water-separation feature. Water accumulates in a bowl below the fuel filter. Frequently this bowl is transparent so that by means of visual inspection it is possible to tell when enough water has accumulated that the bowl must be drained off.

By checking the appearance of the collecting bowl on fuel/water separators, a prospective purchaser can determine whether there is a lot of water being removed from the fuel system or at least how recently the bowl may have been emptied. Water will appear clear, while gasoline is typically slightly yellow looking, and diesel fuel is commonly dyed red. Some boaters prefer trying to flush the water through the engine rather than filtering it out and will use fuel-drying additives. Most of these additives rely on alcohol to emulsify any water trapped in a fuel system, and alcohol is a chemical that most experts recommend against introducing into an engine.

Primary and secondary filters. Fuel should be filtered through both primary and secondary filters, with the secondary or final filter often mounted on the engine itself. Initial filtering can be as coarse as 30 microns (30/100 of a millimeter) allowing emulsified water and foreign particles smaller than this to pass through, although 10 microns is more common. Secondary filters are frequently as fine as 2 microns. All engines require clean fuel, but diesel boaters must be particularly conscious of having an adequate fuel-filtering system and maintaining it regularly. How easy will it be to service the filters on the boat under consideration? If filter changing appears to be a serious problem (perhaps the engine was configured with the secondary filter buried behind a lot of plumbing), there may have been an inadequate number of filter changes in the past.

Fuel Lines

Copper tubing is the material of choice for fuel lines. Copper resists corrosion and can be shaped to fit the available space between fuel tanks and primary filters. The flexibility of copper allows it to avoid becoming brittle and cracking due to continual engine vibrations, It should be possible to follow the run of a fuel line by eye from the tank to the primary and secondary filters, and there should be no leaks at any of the joints. A well-designed fuel line does not contain splices in the middle of a run.

Cooling and Exhaust Systems

Most people are familiar with the cooling of automobile engines through a radiator which transfers heat removed from the engine into the air. Air radiation requires an enormous amount of air to pass across the cooling fins. While a sufficient amount of air can pour through the grille of an automobile, no such phenomenon exists in the engine room of a boat. Provisions must be made to remove the heat in another manner, and a boat has the advantage of operating while immersed in a fabulous heat-absorbing medium: water.

Closed cooling systems. Marine engines with closed cooling systems are cooled by constantly pumping water aboard the boat, where it is circulated around a series of tubes known as the heat exchanger. A permanent engine coolant or antifreeze circulates through the engine block and heads, and flows through the heat exchanger’s tubes. The heat exchanger performs much the same function as an automobile radiator, transferring heat collected by the engine coolant to the much lower-temperature raw water introduced from out- side of the hull. The raw water will also circulate through any oil coolers or turbo after coolers installed on the engine. Oil coolers use a heat exchanger to reduce the temperature of engine oil and will assist in maintaining adequate oil pressure and proper lubrication qualities. Turbo after coolers refrigerate air after it is compressed by the turbo charger, increasing its density so that more oxygen molecules are contained in a given cubic volume, enhancing the combustion process in the engine. Most higher-horsepower diesels are turbo charged, but no gasoline engines for marine applications would ever utilize a turbo.

Raw-Water Cooling

Raw-water cooling systems pump fresh- or saltwater from outside the hull directly through the entire engine cooling system, including the block and heads, without a heat exchanger or an antifreeze coolant. Engines subjected to higher operating temperatures may be more efficiently cooled with a raw-water approach.

Manifold Cooling and Muffling

After circulating through the various heat exchangers found in the engine and through water jackets built into the exhaust manifold (nobody wants a red-hot exhaust manifold in an engine room), the cooling water is pumped back overboard through the exhaust system. Water flowing through the exhaust pipes acts as a muffler to quiet the exhaust and keeps the exhaust tubing from becoming overly hot as well. To make sure that the cooling system is working, boaters develop the habit, each time the engine is started, of watching for the splash of cooling water discharged from the exhaust system.

Raw-Water Strainers

Each engine should be equipped with a raw-water intake strainer to remove seaweed and other debris from the cooling water before it is circulated through the engine. Often these filters are contained in a transparent housing. When inspecting a boat for potential purchase, note the condition of the strainers and whether or not they appear to have been kept clean. A vessel on the market with a green salad in the raw-water strainer may have been operated in a condition where the engine was not adequately cooled, an indication that the previous owner did not pay enough attention to maintenance.

Waters Pumps

A marine engine with a closed Engines and Their Systems – Key Pointscooling system has two pumps that require occasional service to insure that an engine will cool properly. The first is the raw-water pump which circulates water brought aboard for cooling purposes and then pumps it out again. The raw-water pump is the only cooling pump found on a boat with a raw-water cooling system. This pump is ordinarily gear driven, and contains a rubber impeller that is subject to eventual wear, requiring occasional replacement. If a maintenance log has been kept on a used boat, see how recently the raw-water impeller was changed. Some experts recommend changing this impeller annually. Others favor «leaving well enough alone», unless some indication – such as a reduced flow of cooling water from the exhaust pipe or a higher-than-normal reading on the temperature gauge – creates grounds to suspect a deteriorating component.

The second pump is the usually belt-driven engine coolant or water pump which circulates the freshwater and antifreeze mix through the block and heads, absorbing the heat transferred to the raw water at the heat exchanger. The water pump on a marine engine is similar in design and application to that found on the family car. Boaters who venture far offshore will usually have a spare water pump aboard and be confident that somebody aboard has the knowledge to install it if the need arises. When overhauling a gasoline engine, or after about 2 000-3 000 hours on a diesel (check the manufacturer’s recommendations), it’s a good idea to replace a water pump as a preventive measure.

Exhaust Systems

Exhaust manifolds and heat exchangers will have sacrificial zinc anodes. These zincs must be replaced regularly, often three times a year or more, to prevent corrosion of critical internal components and manifold baffling. Exhaust manifold corrosion can, in some cases, lead to complete engine failure. Boats listed for sale often advertise «new exhaust manifold», as he manifold is the component most often requiring replacement due to exposure to heat and corrosive elements. The presence of a few spare zincs in the engine room may indicate that the previous owner took this task seriously. Zincs should be changed frequently enough so that the zinc material on the end of the installation nut will remain in adequate quantity and condition to be effective. In most cases, this will be of sufficient frequency that the brass nut on the end remains clean and bright looking. A zinc nut which has been painted over might be cause for major concern.

Exhaust Elbows and Hose. An engine installed below the waterline will direct exhaust

gases upward to a point above the waterline, then through an exhaust elbow and back down to bilge level, to eventually exit just above the waterline at the stern. The elbow above the waterline helps prevent a following sea from rushing up the exhaust pipe and entering the engine. A well-designed exhaust system incorporates some type of support to bear the weight of the exhaust elbow and relieve strain on the manifold. Connections between the elbow and the exhaust hose should be tight, and there should be no sooty-looking patches on the underside of the deck above the exhaust system. Carbon monoxide can enter a boat through a compromised exhaust hose, so it’s an excellent idea to see that the hose runs unrestricted to the stern and has not developed any rusty or sooty patches along its length.

Dry Stack Exhaust. Most commercial vessels and a few pleasure boats use a dry-stack exhaust system in which the exhaust gases exit through a vertical exhaust pipe terminating well above the cabin top level. The disadvantage of a dry stack is that the exhaust cloud then tends to settle over any boat which might be moving slowly on a calm day.

Read also: Marine Plumbing – Systems and Materials

Electrical Systems

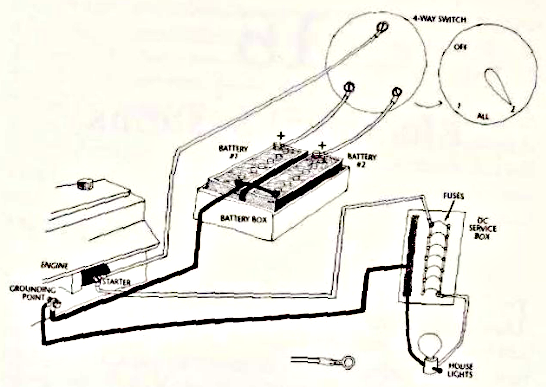

If the engine is the heart of a powerboat and the fuel is the blood, the 12-volt batteries must roughly correspond to an important part of the central nervous system. Without adequate 12-volt power to crank and start an engine, a powerboat is totally disabled. While below decks on a powerboat under consideration for purchase, spend some time evaluating the adequacy, convenience, and condition of the battery system.

The Battery System

Battery Types. Marine batteries have historically been of the wet-cell variety, which requires the occasional topping off with distilled water. When you look into a battery cell, it becomes quickly evident whether the battery has been sufficiently maintained. Batteries in which the electrolyte has been allowed to dissipate to the point where the plates have become partially dry are candidates for replacement in the near future. Many neglected wet-cell marine batteries are allowed to be maintenance free in practice, in spite of the fact that the battery manufacturers never intended them as such. Some of the more costly marine batteries today are of the gel-cell variety, completely sealed units with a gelled electrolyte instead of a liquid. Gel-celled batteries could theoretically be installed sideways or upside down without danger of leakage, and some battery companies claim that their gel cells can be discharged to zero capacity and then recharged with virtually no loss of electrical potential.

A prospective purchaser should note the type of batteries installed on a vessel, and their relative ages. Most batteries will have 2 date-of-sale tag attached for warranty purposes. It is good boating practice to replace entire groups of batteries at a time as having batteries of various ages connected to the same charging system can result in some peculiar recharging irregularities. Gel-cell and wet-cell batteries should never be mixed on a boat as they accept current quite differently when recharging from the alternator or the 110-volt A/C battery charger.

Battery isolation. Any powerboat large enough to have electrically operated accessories should have a minimum of two batteries, with one engine battery reserved strictly for providing power to crank the engine. The 12-volt lights, refrigeration, stereo systems, navigation electronics, ect. then operate from the second, or house battery. These two batteries are isolated from one another by a battery-selector switch which allows a boater to access either the house or engine battery independently(or both at once to facilitate recharging from the engines alternator while underway). This switch is sometimes located in the bilge area near the batteries – probably to reduce the amount of time and wire needed to install it – but it is far more convenient if it is located near a helm station. If the selector switch is in the engine room, it will be necessary for the skipper to visit the engine room after starting the boat on the engine battery to rotate the switch to the «all» or «both» position while underway and to enter the engine room again upon reaching the destination to Switch the selector to the «house» position.

Battery-selector switches also have an «off» position to disconnect the batteries from the boat’s electrical system. Care must be taken that the «off» position is never selected while an engine is running, as severe alternator damage (blown diodes) will most likely result.

Battery banks. Many boats have more than two batteries. Twin-engine boats often have a Starting battery for each engine, and boaters who anchor out for extended periods of time with-out a generator or access to shore power will frequently use a bank of house batteries. A battery bank is created when batteries are connected in such a manner that the positive and negative terminals are wired to the identical terminals on the other batteries in the bank. Connecting the opposite terminals (positive to negative) of two 12-volt batteries creates a 24-volt system which would fry the electrical system of most pleasure craft.

Battery Boxes. Batteries onboard should be contained in battery boxes. A battery box captures any spilled electrolyte, and the cover of the box protects the terminals from coming into accidental contact with a wrench or other metal object, which could conceivably result in a dangerous or damaging electrical short circuit. Battery boxes must be secured by bolts, screws, or straps to prevent batteries from shifting and sliding around the bilge as a boat pitches and rolls in heavy seas.

Battery Capacity. A fair-sized powerboat can easily use 150 or more amp hours of 12-volt power a day, and to maximize battery life it is important not to draw most wet-cell batteries down below 50 percent of rated capacity. A 150-amp-hour-per-day boat (without an onboard generator) anchored out for three days requires a house battery bank of two 450-amp batteries or three 300-amp batteries to avoid discharging beyond the 50 percent level, or the engine needs to be operated at regular intervals to restore battery power. When considering a powerboat, determine whether it has adequate battery capacity for your anticipated usage and, if not, whether there is room available to add additional batteries.

Distribution Panels

With the possible exception of a high-water alarm or a bilge pump, no accessories should be wired directly to the house battery, and nothing should draw from the engine battery except the engine’s starting motor. Wiring circuits for accessories should all terminate at a distribution panel from which either AC or DC current can be switched on or off with circuit breakers. On any boat, but particularly an older boat lacking many of the modern electronic navigation devices, see whether any additional breakers can be added to the panel. If a panel has no room for additional breakers, circuits can sometimes be made available by eliminating obsolete equipment, i. e., a radio direction finder circuit could be used to power a modern GPS chartplotter. (Such changes may have already been made by the previous owner of a used vessel, with or without the benefit of properly relabeling the breakers.) Another option on a boat without adequate electrical capacity at the distribution panel is to install an additional panel elsewhere on the boat. Most distribution panels will incorporate AC and/or DC amp or volt meters to assist the boater in monitoring electrical system conditions.

Wire

One area in which a boat builder’s dedication to quality and craftsmanship is visually apparent is in the type of wiring used and how it is organized. Wire should be of marine grade, typically a high-quality stranded (not solid) wire, to better withstand vibration without breaking. Hot wires, negative wires, and ground wires should all follow a consistent color scheme for easy identification. Well-built boats always have wires arranged on wire looms or conduits, wrapped in bundles and well secured. Lack of basic wire organization could indicate a hurry-up attitude in a vessel’s construction or subsequent modification. The wires behind the service panel should not look like a rat’s nest. Wire nuts so commonly used in household wiring have no place in the marine environment, where wire connections should be crimped or swaged with proper fittings and sealed against moisture. Heat-shrink tubing is becoming commonplace for sealing electrical connections. Although electrician’s tape can be used for sealing a properly fastened connection, it should never be used to wrap two wires that are just simply twisted together.

Inverters and Generators

While most electrical items on board are operable in 12-volt DC mode, occasions arise when it is desirable to operate power tools, microwave ovens, or other 120-volt AC electrical items when not connected to shore power. An inverter or motorized generator can be used, depending on the space available and the amount of power required.

Inverters. An inverter is like a battery charger operating in reverse. Instead of using AC power to make DC current for purposes of charging a battery, an inverter discharges a battery by withdrawing DC amperage and changing it to 110/120-volt AC current. An inverter takes up very little space and can be accommodated on practically any sized boat. Since inverters are solid-state electronic devices, they operate quietly and unobtrusively. Inverters are primarily suitable for intermittent or occasional AC usage, such as running a TV/VCR for a few hours in the evening or plugging in a pot to brew breakfast coffee. Inverters will ultimately draw the house battery down to the point where it will need to be recharged by an onboard generator, running the main engines to activate the alternators, or connecting to shore power and allowing the onboard battery charger to restore potential amperage. Most inverters incorporate a system to shut the inversion process down when the battery level becomes critically low.

Generators. For high electrical loads such as electric space heaters, hot-water tanks, and all-electric galleys (as well as for boats which will be anchored out a lot), a gasoline or diesel generator makes a lot of sense. Boats with all-electric galleys need a system which will supply 110-volt power to refrigerators and stoves while underway. A high-output alternator driven as an accessory by the main engine or a separate AC generator may be used to create large amounts of 110-volt current. Some boats incorporate very small one-cylinder diesel engines, consuming about a quart of diesel per hour, dedicated to the sole task of running a DC generator and creating a source with which to recharge the battery banks.

Generators do occupy precious space on a boat and add to the costs of acquisition and maintenance, which may explain why generators are almost never found on boats less than 32 feet. At 38-40 feet and above, it is fairly rare for a boat not to be equipped with a generator. Generators are available in either gas or diesel versions and can draw fuel from the main fuel supply. A gasoline generator in an enclosed space will need to have a blower fan operating fairly constantly when the vessel is not underway or has slowed to the point where the normal air flow through the engine room may not be sufficient to expel fuel vapors. A well-installed generator is properly grounded, properly vented and exhausted, well mounted (not too close to the main stateroom if possible), and contained within a sound shield to control noise. Noise is the number one generator-related complaint. Many boaters have bitter memories of nights spent in what should be pristine wilderness anchorages listening to the chugging exhaust of a neighboring boater’s generator. Some generators installed in engine rooms can be rigged to provide «get home» power to a prop shaft and allow a vessel to limp in, should the main engine fail.

Electrolysis and Corrosion

Whenever two diverse metals are connected by a conductive medium such as water or battery acid, the more noble metal will extract electrons from the less noble metal, and corrosion will occur. Corrosion on a boat is controlled by the use of ground wires and sacrificial zinc anodes. Zinc is one of the least noble of metals, and by attaching zinc fittings to prop shafts, rudders, trim tabs, etc., the electrical charges which must absorb electrons from other metals obtain these electrons from the zinc rather than from the critical and incredibly expensive structural components of the vessel.

Grounding. Electrical systems on boats are grounded to the water surrounding the hull (except when operating on shore power). Metal fittings which contact water, such as bronze seacocks, should have a ground wire running from each fitting to a grounding strap. This ground wire will absorb stray electrical currents which accelerate corrosion. Bronze fittings which are turning green and covered with a crumbling, powder like residue are not properly grounded and may need to be replaced if the corrosion process cannot be arrested in time. As previously noted, grounding the prop shaft is an excellent idea, accomplished by placing a flat, metal shaft brush where it will ride across the top of the shaft as it turns, and connecting the brush to the grounding system.