The reasons for buying a used boat are primarily financial: used boats are less expensive than new boats. How much less usually depends upon the age of the used boat. It also depends upon the cost of a new boat offering the equivalent features of the used boat. In this material we will consider the main aspects: how to buy a used boat and what documents are needed for this.

Thus, if a 1985 XYZ-30 costs $40 000 and $39 000 is being asked for a 1979 XYZ-30 with the same equipment, a used boat buyer would be unlikely to buy the 1979 unless he knew that in 1979 the manufacturer had used platinum for ballast rather than lead.

Barring something of this sort, the informed potential buyer of the XYZ-30 is going to make the owner an offer lower than $39 000, an offer which, to him, represents the point at which he will decide to buy the boat new or look elsewhere.

Therefore, he might offer the owner, say, $32 500 – and the owner would probably agree to sell. In fact, he is very likely to sell because, in 1979, the present owner bought the boat new and complete for $28 500.

Yes, Virginia, the prices of new boats have gone up. As a matter of fact, between the fall of 1973 and the spring of 1974, the prices of new sailboats rose about 30 percent. As I pointed out earlier, read the article «Manufacturing of Fiberglass Boats and Design FeaturesFiberglass Boats and Design Features of Manufacturing Their Parts», most of the cost of a boat is the materials, so boat prices are, naturally, very sensitive to increases in the cost of materials. As we all know, the price of everything has risen, especially petroleum derivatives, of which polyester resin (which is used to glue the fiberglass together) is one.

If you are inclined to be put off and to brood about these facts, pause and reflect upon what has happened to the market value of your house since you purchased it. Sailboats are very close to being real property, too. They are simple and are made of very durable materials.

A recent study of a Coast Guard cutter that had seen twenty years of hard service showed no weakening of the fiberglass sandwich of its hull. The Rhodes Bounty 40-footers that first were built three decades ago are prized boats because they were extraordinarily strongly made due to initial conservatism in the use of a then-untried material, fiberglass. They are overbuilt to a fare-theewell.

I myself have been going happily to sea aboard a friend’s twenty-four-year-old retired ocean racer, a boat that won the Southern Ocean Racing Circuit (SORC) two years running and had really been pushed hard when my friend bought her.

So, fiberglass sailboats are likely to be around for a long time. And, like houses, they are a reasonably good hedge against inflation. You might earn interest by keeping your money in a savings bank, but you won’t have nearly as much fun or adventure.

The Financial Side

If anything, used boats are a better investment than new ones. As I’ve said earlier, the material used for boats is very durable, and only the sails, engine, and electronic instruments wear out at any appreciable rate.

Even then, engines can be replaced quite cheaply ($1 500 at this writing will rebuild and reinstall your present gasoline auxiliary engine). The same is true of sails and electronics. Except on outand-out racing boats, these items are scarcely a significant part of the investment in an auxiliary sailboat.

Still, as the boat gets older, these things do wear out. Therefore, even though the capital part of a used boat becomes a higher percentage of the boat, the expenses are going to be higher, too. In a way, one balances the other: less depreciation than with new, but higher expense.

As with new boats, financing is available for used boats on about the same terms.

What is the down payment when buying a used boat?

A down payment of about 20 percent will let you buy a used boat, assuming your credit history is good. Generally, terms are about the same, too – up to 15 years, depending upon the amount borrowed. As with new boat financing, it is important to check for any prepayment penalties because the odds are you won’t keep the boat very long: you’ll be moving up sooner than you think.

Inflation and the consequent rising prices of new boats are keeping the selling prices of used boats from going down; if anything, they are going up. This is particularly true of certain specific used boats which have stood the test of time and which the market has found to be particularly desirable, for one reason or another. Some of these boats are briefly described in the point «Benchmark Boats» delow.

The Fifteen-Minute Survey

A major difference between the purchase of a new boat and the purchase of a used boat is that the used boat carries no warranty. As a rule, this is explicitly stated on either the listing, which gives the written specifics of the boat, or the Purchase Agreement, which you sign when you make the initial commitment to buy.

Once the money has passed from you to the broker or owner and you have received the Bill of Sale, she’s yours – virtues, vices, wants, and all.

Therefore, it is even more important for you to satisfy yourself that the used boat is structurally sound. Now, normally, when you make an offer on a boat, your offer is contingent upon a marine survey carried out by a competent individual, whom you pay to go over the boat and to alert you, in a written report, of her defects.

Since this is a somewhat expensive procedure, about $10 per foot of overall length, it will help if you can at least make a reasonable appraisal of her yourself to determine whether the boat is sound enough for you to invest in a full-fledged survey.

The techniques for doing this are basically the same as those discussed in the article «Step-by-Step Guide to Choose the Boat for YouHow to Select a Boat: the Main Aspects You Should Pay Attention»; namely, use your eyes and look at certain key areas of the boat.

As with a new boat, look at the lifelines and stanchions, seat lockers, hatches, and hardware on deck. When you are below, open the easily accessible lockers and look at the hull-deck joint, both from the point of view of structure and to spot any signs of leakage.

If the lifeline stanchions (posts) show signs of leaking below, these can be sealed up. But leaking of the hull-deck joint can be a major problem that usually requires lifting the whole deck to fix properly.

A good area to look for leaking is in the hanging locker. No need to rip the boat apart; just look where you readily can. Inside the hanging locker is also a good place to check the secondary bonding of the bulkheads and chain plate attachments.

If the mast is stepped through the cabin, take a look at the mast step for signs of heavy corrosion. If the mast is deck stepped, check for signs of sagging at the bulkhead or separation of bulkhead and compression column; check that the support is continuous, just as you did when looking at new boats.

Check the bilge. This will reveal the general level of housekeeping the boat has had. Diesel-powered boats often have very black bilges, due to the fact that these engines continually exude minute amounts of lubricating oil and diesel fuel from their many highpressure fittings. Keeping the bilge clean keeps down the smell, not only of the diesel fuel itself, but also of the fungus which likes to grow in it.

The condition of the stove and the head will also give clues about prior care. Try the pressure pump on the stove and the pump in the head. The condition of all these items will help you to make an intelligent offer.

Just for a general impression, take a look at the engine. This won’t tell you much except that it’s there and whether it’s a diesel or not (gas engines have spark plugs; diesels don’t). Amazingly enough, some owners don’t know what kind of engine their boat has.

The exterior of the engine won’t tell you much, in all probability, but you can ask some hard questions if it’s badly rusted and shows signs of neglect – although I’ve seen some pretty vile looking engines that ran beautifully and checked out fine on survey. One that looks dead, however, might be dead!

If there are sails below, pull the corner of one out of its bag to see if it seems reasonably clean and serviceable. The corners take the loads and are the best indicators of the probable use the sail has had.

Read also: Key Points for Buying and Selling a Boat

All this doesn’t take much time, but you will have given the once-over to the major aspects of the boat – deck, gear, hull-deck integrity, rig, engine, and sails.

As a general guide, the three things most commonly wrong with used boats (aside from general grubbiness) are frozen (unworkable) seacocks, worn cutless bearings, and misstated model years – that is, the boat is one to three years older than stated in the listing.

You can check this last item by knowing how to read the hull identification number, which, by law, must appear on the transom of boats built for the United States market after November 1972. The hull identification number is a twelve-element string of letters and numbers arranged in the following order: three letters that designate the builder, two numbers or letters or combination that identify the model, three numbers that tell which number this particular hull is in her series, and four numbers or combination of letters and numbers that tell when construction began. Here are several examples:

Deciphered, this says this Pearson (PEA) 30 (48) is boat No. 123 of her model and that construction began in April (04) 1974.

This, of course, is the same boat, but the building date is given in a different code – the «model year» code. Like cars, boats are quite often built in designated model years, which generally begin in August, which is designated Month A. September is Month B, October C, and so on. The «M74I» indicates April (the I month) 1974 also.

Had you been looking at a Pearson 30 built in September 1973 (second month of the 1974 model year), the hull identification number could have been:

I am making something of a point of all this because it is very important to get it right. The buying and selling of a boat includes both money and emotions, so an item like a wrong model year can easily be perceived as misrepresentation, which, at worst, will vaporize the deal. At best, it will cost the seller real money, far more than the model year differential, which, in sailboats, is nominal.

You don’t, of course, need to take the time to do this unless the boat truly appeals to you for her looks, layout, finish, rig, or price. If the boat does appeal to you and you go through this process and find her worthy, you will be in a good position to make a realistic offer on the boat and to evaluate the survey report intelligently when you receive it.

Case History

In the fall of 1969, Mr. and Mrs. Jones came into our office looking, they said, for a fairly decent, used 26-footer. After talking with them for a while, I learned that they had a 22-footer with which they had been sailing and cruising for two years. One of the things they wanted to know was whether they could trade in their present boat.

I said our company would take their present boat if they bought a new boat. Since a Used Boats for Saleused boat, however, ordinarily belonged to an individual and not to our company, it was not normally possible to arrange a swap. I suggested that they had a choice to make: to own no boat for a while or to own two boats for a while.

That is, they had either to sell their boat and then look for a replacement or buy their next boat and then sell their present boat.

Well, they decided they would go with the second choice. That way, they would not run the risk of being boatless if they were unable to find a suitable 26-footer by spring.

Having by now spent some time talking with the Joneses about their boat and what they liked and did not like about it and other boats, I had a boat in mind I thought would suit them right down to the ground. It was the used 26-footer I had shown to the Smiths earlier.

Mrs. Jones liked the boat very much and, unlike Mrs. Smith, was not the least put off by the rusty can rings in the icebox. A little Zud, she said, would remove them right away. Mr. Jones liked the boat, too, and wanted to know what was being asked.

When I told him, he was surprised. He had been watching the New York Times ads, and the price I had given him was about $1 000 below the (then) normal asking price of $8 000.

I told him that the boats were actually trading hands for about $7 500 and that it looked to me like this owner really wanted to sell the boat and was simply being realistic.

Mr. Jones seemed to think there might be something wrong with the boat, so I suggested that he and I look at the boat closely together and, essentially, do a fifteen-minute survey.

We did this and the boat looked good to both of us. I then suggested that he buy the boat, since the price asked was more than fair, or that he at least make the owner a slightly lower offer.

At this point, Mr. and Mrs. Jones demurred. It was the first boat they had seen and they just couldn’t decide that fast. I replied (sounding very much like a high-pressure salesman, I’m sure) that that was because I had gone through a process of selection for them and felt that this boat most nearly fit their requirements.

Well, they were still hesitant, so in order to clear the air and let them relax, I suggested that we look at two or three other boats in the same size and price range. We climbed down the ladder, and, as we were walking toward my car, one of the other brokers in our office came by with a nicely dressed young couple and asked for the key to the 26.

You guessed it. In the time it took us to drive around to the other boats, the young couple made an offer $250 lower than the price asked, and the owner agreed to sell. I wasn’t too surprised, because this kind of thing happens daily in our business. But the Joneses were flabbergasted. They had no idea things could happen so fast. Boats, after all, are luxuries not to be snapped up like necessities.

Boats may be luxuries, but after eight years of selling them, I can tell you they carry a heavy emotional freight. Perhaps this is because of the Walter Mitty in all of us, perhaps to other things, but a clean boat, fairly priced, does not sit around ownerless for long. And this is as true in a recession as in a boom. Maybe it’s truer in a recession; pennies may be safer in a boat, especially if the downturn is inflationary.

I eventually found the Joneses another boat of the same type and they bought it for the fair market price. Their indecision cost them about $750, but I don’t think they acted wrongly. They didn’t know me well enough to evaluate my «baloney quotient», if you will, and were simply being conservative by wanting to check the market further before making a decision.

It was frustrating for me because I knew that the 26-footer was the right boat for the Joneses and, in fact, they reached the same conclusion. It was also frustrating for them, as any lost opportunity is.

The main point of this story is, I guess, that sailboats are considered a good thing in this country, and good things have a ready market in the United States.

Buying a Used Boat Step by Step

There are two ways to buy a used boat: directly from the owner or How to Choose a Boat Broker: Tips on Yacht Sales, Consignments, Fees, and Trade-Insthrough a broker. Since I used to be a broker, I propose to discuss this manner in which a used boat sale takes place, since this is the way most used boats are sold.

The principal functions of a broker are:

- to negotiate the terms of the sale and see that they are carried out;

- to act as an escrow agent for the funds delivered by the buyer and for the Bill of Sale delivered by the seller until the terms of the Sales Agreement are complete.

He then delivers the Bill of Sale to the buyer and the funds (less his commission) to the seller.

In carrying out these functions, the broker performs several other services. Chief of these is getting the information on the boat into the marketplace. This is done by means of a form called a listing (see example for ABC Yacht Brokerage below) that contains the written details of the boat’s history, equipment, and asking price.

Type: XYZ 30 AUX. SLOOP

LOA: 29′ 9 1/2″

LWL: 25′

Beam: 9′ 6″

Draft: 5′

Headroom: 6′ 1″

Builder: XYZ Yachts

Designer: M. E. Wellknown

Year: 1974

Engine: Universal Atomic 4, 30 HP gas built in 1974

Tanks: Fuel – 20 gallons Water – 22 gallons

Electrical equipment: Two 12 volt batteries, control panel, battery selector switch, alternator

Electronic equipment: Fathometer, speedometer, log, loran, VHF-FM

Construction: Fiberglass hull and deck; blue haze hull, white deck; №3 560 lead ballast; №8 320 displacement

Sails and Rigging: Main, jib, 150 % genoa

Aluminum mast, stainless steel rigging, two rows jiffy reefing points, mainsail cover, genoa gear, mainsheet traveller, winch handles, Barient №22 genoa sheet winches, two halyard winches

Accommodations: She sleeps six (6) – «V» berths forward, convertible dinette, quarter berth with storage under. She has a marine head with sink. Galley equipped with sink, ice box, stove

General Equipment: Anchor, anchor line, chain, dock lines, fire extinguishers, life preservers, horn, fenders, boat hook, bilge blower, manual bilge pump, curtains, carpeting, fabric upholstery, bulkhead-mounted compass, bow and stern pulpits single lifelines, boarding gate, screen, swim ladder, flag halyard

Location: Westchester

Price: $28 000,00

These listings are usually kept in ring binders arranged according to overall length of the boats. After your initial contact with a broker, he will usually suggest several possibilities to you and show you the written listings of boats he thinks would fit your requirements. Often this process covers several weeks: the broker calls you when he thinks he has something of interest for you or simply sends you a photocopy of the listing of the boat he feels would be of interest.

Brokers also advertise, and you should keep an eye on the ads. Sometimes an advertised boat will excite your interest and yet be in a location or of a type your broker does not have in mind for you. You can have him check it out for you.

Once you have found one or two boats that are particularly interesting, the next step is to go and see them. Be aware that finding a used boat involves a lot of running around. Just because a broker has a listing on a boat does not mean that she is just around the corner – our office had listings from as far away as Australia.

Let’s say you have looked at several boats and zeroed in on one. You do the fifteen-minute survey and the boat looks good. What’s next?

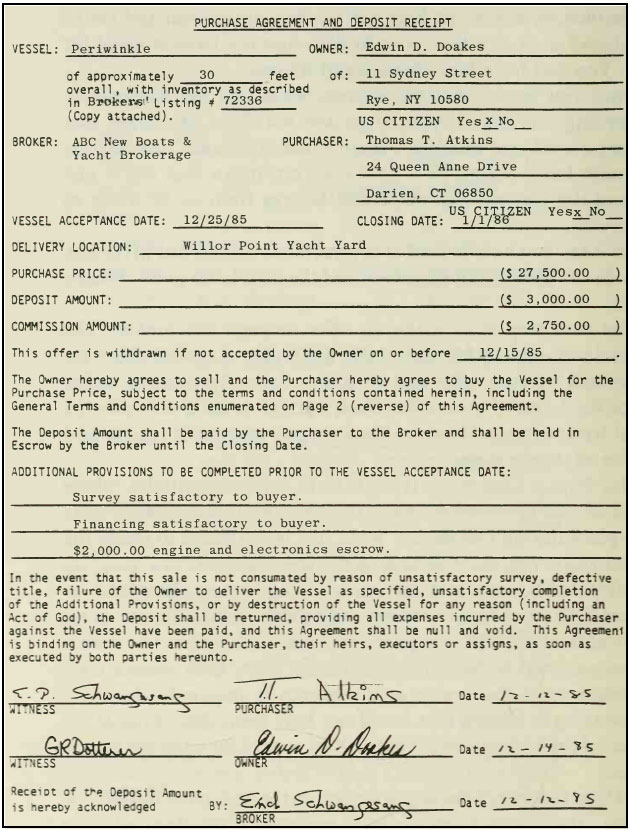

The next step is to make an offer through the broker. The normal procedure is for you to give the broker a deposit check for 10 percent of your offer and to sign a Sales Agreement, which states the terms of your offer. Such a paper is filled out with the usual terms of a used boat, or «brokerage», sale and is reproduced below.

- The Broker offers details of the Vessel in good faith, but does not guarantee the accuracy of this information nor warrant the condition of the Vessel. The Purchaser may instruct his agents or surveyors to investigate such details as he desires validated.

- The Owner agrees to pay the Broker the Commission Amount on the Closing Date as commission for finding a purchaser for the Vessel. The Commission Amount shall not be affected by any adjustment in the Purchase Price agreed to by the Owner and Purchaser as a result of conditions found during survey.

- The Purchaser may have the Vessel surveyed at his expense and shall give written notice of acceptance or rejection of the Vessel on or before the Vessel Acceptance Date. If written notification is not received by the Broker by said date, it shall be construed as acceptance of the Vessel by the Purchaser. The Purchaser may refuse to complete this purchase if the Owner refuses to repair, at his expense, the essential items of repair as required by the survey or refuses to adjust the Purchase Price to compensate the Purchaser for essential repairs.

- In the event, after written or construed acceptance of the Vessel, the Purchaser fails to pay the balance of the Purchase Price and execute all papers necessary to be executed by him for the completion of the purchase pursuant to the terms of this Agreement on or before the Closing Date, the sum this date paid (Deposit) shall be retained as liquidated and agreed damages, and the parties hereto shall be relieved of all obligations under this Agreement. In this event, one-half of the Deposit shall be retained by the Owner and one-half shall be paid to the Broker, except that the amount paid to the Broker may not exceed the Commission Amount.

- The Vessel is being sold and purchased free and clear of all debts, claims, liens and encumbrances of any kind whatsoever, and the Owner warrants and will defend that he has good and marketable title to the Vessel and the lawful right to sell the Vessel. The Owner will deliver all necessary documents for the transfer of title to the Purchaser or, at the Purchaser’s request, to the Broker on or before the Closing Date.

- If any Sales Tax is applicable, it is the responsibility of the Purchaser to pay it.

- Until the Closing Date, the Owner shall keep the Vessel insured for a sum in excess of the Purchase Price. In the event of any loss, all sums recovered or recoverable on account of said insurance shall be paid over or assigned to the Purchaser on the Closing Date unless the Vessel shall previously have been restored to its former condition by the Owner.

- On or before the Closing Date, the Owner shall deliver the Vessel to the Purchaser at the Delivery Location.

- The terms Vessel, Owner, Broker, Purchaser, Vessel Acceptance Date, Closing Date, Delivery Location, Purchase Price, Deposit Amount and Commission Amount refer to the information identified on the front of this Agreement.

This form is filled out as it might be in northern latitudes, where boats are laid up out of the water from fall until spring. Many sales take place during this period, when it is not possible to check the engine operation or condition of the electronics.

In order that the sale may go forward and the title pass, the broker holds what is known as an «engine and electronics escrow». This is a sum of money withheld from the seller when the proceeds of the sale are paid over to him. If, when the boat is commissioned in the spring, something more than routine commissioning of the engine or electronics is required – that is, if something is broken that could not have been discovered at the time of the survey – repair of the item is paid for from the escrow fund.

Thus, the seller’s liability is limited to the amount of the escrow. If the boat has an unusually large engine or if the electronic gear should be unusually elaborate or complicated, the escrow fund will be larger.

This, too, is a negotiated item. You state what you want when you make your offer and, if the owner balks, you negotiate through the broker until an agreement is reached or not reached.

If there is no agreement because of price, because other terms of the offer are not met, or because you don’t find the survey satisfactory after acceptance of the offer, then the broker returns your money.

If your offer is conditional on a satisfactory survey, say so in writing. Then, if the survey is not satisfactory, you can withdraw or change your offer. After you reach an agreement, which happens about 95 percent of the time, the broker will deposit your check and hold the funds until the survey is carried out.

Assuming the survey is satisfactory to you and you or the broker has been able to arrange financing, the balance of the money is paid to the broker, who, by this time, has a Make the Essential Paperwork for Boat Sellingsigned Bill of Sale from the seller.

He gives the seller his net proceeds and you the Bill of Sale. And there you are, the proud possessor of a new light in your life.

I think this is a good place to say a few words about yacht brokerage. When you get to the point of deciding to buy a used boat, I think there are a few commonsense things you can do to ensure that you get a good view of the market and pay only the fair market price for the boat you decide on.

First off, I think you want to find a company that is genuinely in the used boat business and that sells a sufficient number of boats of all sizes to have a good idea of what the market is, in fact, paying for X, Y, or Z boat.

To do this, look at the ads in the brokerage section of a national magazine such as:

- Cruising World,

- Yachting,

- Sail,

- Motor Boating and Sailing,

to see which companies put forth a respectable list of boats of the size and type you are interested in.

Many companies sell both new and used boats, and a close look at their ads will show you where the emphasis is. Nationally available, in a library if not at a local newsstand, you can look at the boating advertisements in the sports section of the New York Times every Sunday with the same thoughts in mind: who seems to be in the used boat business and who doesn’t?

Further along these lines, you may want to try to assess the broker with whom you are dealing. There is no graduate degree in yacht brokerage, you know, so you won’t see a degree on the wall to attest to his competence. Most states do not require that yacht brokers be licensed. Yacht brokers are self-taught and their degrees of knowledge and experience may differ widely. As you talk with different brokers, try to decide what kind of job he can do for you. Evaluate him the same way you would evaluate a doctor, dentist, lawyer, or teacher – unless you assume competence in those people just because they have embossed paper hanging on the walls.

Remember that, although the seller is paying this individual his commission from the proceeds of the sale, you are, in a sense, able to hire his brain to ferret out the right boat for you from among a wealth of possibilities. This means that you are relying on his experience and integrity to see you safely – and sanely – through the entire process of buying a used boat. Like any other arena of enterprise, the boat business is a collection of people. I don’t think this arena contains more clowns and charlatans than any other. Nor does it contain fewer.

Benchmark Boats

As you undoubtedly realize by now, there is no perfect boat, just as there is no perfect anything else. Like people, boats have warts and have to be accepted (or rejected) as a whole. It is easy to fault individual items on practically any boat, but what you are buying, finally, is a whole complex of many factors. So, you have to come to the conclusion when you select your boat that, on balance, she suits your intended purpose.

The list that follows is made up of brief descriptions of boats that, to my mind, have, in the main, successfully resolved the many elements that go together to make up a total boat. By and large, these boats have passed the tests of time and the market. Their qualities, good and bad, are well known, and it is my feeling that, if you are seriously considering a boat in any particular size range, you would be wise to take a look at the boats on this list in the same general size or price range, because the boats here continue to be sought after in the marketplace. They are not will-o’-the-wisps.

In using this list, please remember that the prices given are approximate and based on sales taking place in the fall of 1984 in the Northeastern United States:

- Bristol 22 Caravelle ($6 000-$7 000). The proportions of this boat are exceptional. She is a handsome little vessel with exceptional room below and a proper-sized cockpit for a cruiser. She sails fast and dry for her size. She comes as near as anything I’ve seen to what used to be called a «tabloid cruiser».

- Columbia 22 ($6 000-$7 000). Her proportions are not quite as pleasant as the Bristol’s, but her design emphasis is a little different: relatively more space is allotted to the cockpit and, so, she is more daysailer/cruiser than an out-and-out cruiser. A realistic choice for the way most people actually use boats in this size range.

- Pearson 22 ($6 000-$7 000). Designed as a MORC (Midget Ocean Racing Club) boat, she is low and light and much less roomy than the Bristol or Columbia. Still, she is very easy to look at and, like many successful racing boats, a real witch under sail.

- Sailstar Corsair 25 ($7 000-$8 000). A very unusual boat. She has nearly 6 feet of headroom and, yet, the overall look of the boat is traditionally pleasing. Her roominess is achieved by a quite deep and full underwater hull shape, but the price paid is tenderness. She heels to a rather large angle quickly before stiffening up – remember the soft drink can.

- Islander Excalibur 26 ($8 000-$9 000). Very light, very fast, great fun to sail. The house is low and so is the headroom below – 4 feet 11 inches. But you have excellent visibility from the cockpit. Generally, sailing qualities are weighted more heavily in this design than creature comforts. In our area, she was top MORC boat for several years until the advent of the Ranger 26.

- Pearson 26 ($12 000-$15 000). Introduced at the New York Boat Show in 1970, this boat, to date, has reached hull number 1 300. The chief reasons for this astounding success are the fact that most women can stand up in it (headroom, 5 feet 8 inches); it has a sensible layout, which includes a private head; and it marked a turn on the part of the manufacturer to a less expensive type of interior, thereby saving money and resulting in a price advantage, in 1970, of a solid $1 000.

- Pearson Ariel 26 ($8 000-$10 000). Headroom is achieved in this boat by raising the after portion of the cabin above the forward part into what is called a doghouse. As a result, the hull form is a stiffer one than the Corsair’s. Like the Corsair, she has a full-run keel of the modern type. Some have inboard engines, and these generally sell for $500 to $1 000 more than the outboard-powered models. She will outsail the Corsair, but not the Excalibur.

- Ranger 26 ($9 000-$11 000). Like the Excalibur, this boat is somewhat shy of headroom (5 feet 5 inches) and, as in the Excalibur, the view from the cockpit is excellent for this reason. The boat has had quite a successful racing career and, while not at the top anymore, she is a good all-around boat that has the advantage of being very good looking.

- C & C 27 ($21 000-$28 000). A totally modern fin keel, spade rudder boat, which somehow gets 6 feet 1 inch of headroom into this size while keeping visibility from the cockpit, stiffness, speed, and striking beauty of line. There are actually two versions of this model. The first, introduced in 1971, is a little short in the cockpit. Later models have nearly a foot added at the stern and are actually 28-footers. This is the reason for the wide spread in price. Traditionally, the C & C 27, Pearson 30, and Sabre 28 are considered together, as they are in roughly the same price and quality category.

- Tartan 27 ($13 000-$18 000). At the other end of the spectrum from the C & C, this little keel/centerboarder has a full-run keel with attached rudder. Her shallow draft makes her desirable in bay areas. Introduced in the early 1960s, this boat continues to sell steadily, year after year. Our office had the happy chance to sell boat number 600. Despite my general attitude toward split rigs, I find this boat particularly appealing as a yawl.

- Pearson Triton 28 ($11 000-$15 000). Production began in 1959 on this very conservative design. She has a full-run keel with attached rudder and offers 6 feet of headroom, enclosed head, and inboard power. When production ceased in 1967, more than 750 Tritons had been sold. The boat is narrow by today’s standards, but an awful lot of people have sailed many miles in Tritons. I doubt there will ever cease to be a market for Tritons.

- Sabre 28 ($25 000-$30 000). Like the C & C 27, a handsome boat with good headroom and fine finishing. She has a skeg-hung rudder rather than the pure spade of the C & C 27 and Pearson 30.

- Allied Seawind 30 ($25 000-$35 000). The first fiberglass boat to sail around the world, this boat is usually rigged as a ketch. Her hull form is conservative, shortended, and full. As a result, she is initially somewhat tender, but this probably promotes an easy motion at sea, and the boat is an excellent all-around boat, even if she’s on the slow side.

- Dufour Arpege 30 ($20 000-$25 000). A strikingly original boat at the time of her introduction (about 1967) and still so. By placing the head all the way forward in the bow of the boat, the designer was able to create an interior layout that includes a large, sit-down chart table and berths located so that all are usable when the boat is under way. If you plan to do much sailing at night, look at this boat.

- Pearson 30 ($22 000-$28 000). Like the C & C 27, a fin keel, spade rudder boat and an even bigger market success. Introduced in 1971, there are now lots of Pearson 30 owners. With this boat, the manufacturer capitalized on the lessons learned from their 26: people did not necessarily judge a boat solely by its interior. You could go to a plainer interior, provided you did not strip the essential boat and did pass the savings along. The boat is big, strong, good looking, wellmannered, and fast, and has a thoroughly sensible layout.

- Bristol 32 ($27 000-$32 000). This boat, like the two that follow, has the modern full-keel, attached-rudder underbody and, while on the slow side, she’s a handsome, traditional-looking craft, well suited to leisurely cruising.

- Pearson Vanguard 32 ($22 000-$27 000). When first introduced in 1964, a Vanguard equipped to race cost about $21 000; cruise equipped, about $18 000. This is a good illustration of the fact that money invested in a fiberglass sailboat is just that-an investment, not an expense.

- Allied Luders 33 ($32 000-$37 000). This boat has a fuller underbody than either the Vanguard or the Bristol 32 and is highly prized among cruising sailors. She has a reputation for being very strongly made – a point upon which you can satisfy yourself.

- Morgan 34 ($28 000-$33 000). Designed by an avid sailor, this boat has wide decks, low house for good visibility from the cockpit, and very good looks. She is the shoalest of the keel/centerboarders, drawing only 3 feet 3 inches with the board housed. The normal underbody is full run with attached rudder, although a few were made in 1968 with spade rudders separated from the keel. Introduced in 1967, the earlier boats are prized because they have bronze centerboards. Two layouts were made and both are popular, although I personally prefer the aft galley model.

- Tartan 34 ($31 000-$37 000). Like the Luders, Tartans have a reputation for great strength. This boat has been in production for about ten years. The underbody is the more modern fin with a large skeg in front of the rudder. The Tartan is a keel/centerboarder and, due to her shoal draft, is highly prized by shoal-water sailors and gunkholers.

- Allied Seabreeze 35 ($33 000-$38 000). Very similar to the Pearson in looks, the interior is richer: Allied continued with teak bulkheads when Pearson switched to Formica after 1968. Also a keel/centerboarder with full-run underbody.

- C & C 35 ($35 000-$40 000). This was a true breakthrough boat that demonstrated that it was possible to have a fast, highly competitive boat that was a superb cruiser due to strength and good, sensible layout. To top it all, she’s beautiful – not in a traditional way, but in a modern way all her own.

- Hinckley Pilot 35 ($45 000-$75 000). A very traditional design with low topsides and sweeping sheer line. While somewhat narrow and cramped by today’s standards for a 35-footer, this boat, like all Hinckleys, is very strongly made, and is beautifully and lavishly finished with varnished natural woods.

- Pearson 35 ($34 000-$55 000). One of the few traditional-looking, full-keel boats remaining in production, she has reasonably shoal draft, thanks to a centerboard. Her distinctive characteristics are the largest cockpit of any boat her size, greatest headroom (6 feet 4 inches throughout), and a truly private forward cabin. After fifteen years, she’s still in production, which accounts for the wide price range.

- Pearson Alberg 35 ($25 000-$30 000). Big brother to the Ariel and Triton, very much like the Luders in hull form, this is the boat that introduced hot – and cold-pressure water and showers to small cruising boats. Like the Luders, although no longer built, they are much sought after by conservative sailors.

- Chris Craft Apache 37 ($33 000-$38 000). This is an early fin keel, spade rudder design. The keel is made of cast iron and is bolted into the canoe body of the boat. The boat is very good looking and has a reputation for strength. Close reaching in fresh breezes, a well-sailed Apache can keep up with many of the more modern designs.

- C & C 38 ($65 000-$70 000). A boat in which, to my eye, everything comes together. Just looking at her makes me feel good. Her size is just right for a coastal cruiser for two to four or a family, the layout practical, and the construction light, but strong.

- Pearson 39 ($60 000-$75 000). This is a modern keel/centerboarder with a separated rudder mounted on a large skeg. Like the Pearson 35, she has a nice private cabin forward and her layout includes a sit-down chart table aft, opposite the galley. Also like the 35, she has an unusually large cockpit, which promotes comfort under sail and later, at anchor, when the cocktail flag is hoisted.

- C & C 40 ($90 000-$105 000). Very successful in the racing circuit, this 14 000-pound 40-footer would be a suitable cruiser, but only for experienced sailors, since the rig can be quite a handful.

- Cal 40 ($40 000-$55 000). This is the boat that really blasted a hole in the theory that a light boat could not be strong and seaworthy. In the ten years following her introduction, she dominated racing; as a result, the Cal 40 is thoroughly tested in the school of hard knocks – ocean racing. The boat weighs only 15 000 pounds and has a fin keel (which is conservatively long, by today’s standards) and a freestanding spade rudder. With the racing rule change from CCA to IOR, so many Cal 40s came on the market that there was a glut and, for a while, you could buy a used one for about $20 000.

- Hinckley Bermuda 40 ($85 000 and up). This boat has been in production so long that it is hard to indicate a price: $120 000 is about what boats built in the early 1970s have been bringing. Earlier vintages may bring less, but it is difficult to imagine even the oldest selling for less than $85 000 if it’s at all well kept; new Bermuda 40s approach $200 000. These boats are superbly built and finished and have been thoroughly wrung out by hard racing and long-distance voyaging. The hull configuration is traditional, with sweeping sheer and low cabin trunk. She is a keel/centerboarder with attached, barn-door rudder.

- Olson 40 (around $90 000). At 10 000 pounds displacement, she is about the lightest 40-footer around, as well as one of the most carefully built. Constructed more like an airplane than a boat, she’d be my handsdown choice for coastal cruising because she’s truly fast and easily handled due to the fact that her rig (because of her lightness) is small and simple.

- Rhodes Bounty 41 ($50 000-$60 000). One of the earliest boats to be built in fiberglass in the United States and, as a result, they tend to be overbuilt. For this reason, they are sought by super-conservative sailors and those with serious intentions of cruising oceans. By today’s standards, they are too narrow to allow spacious accommodations and the cockpits are small. But these are actual virtues in the eyes of an incipient ocean voyager.

- Rhodes Reliant 41 ($85 000-$105 000). With this boat, Phil Rhodes took a layout that had previously been used only in much larger boats and adapted it to a 40-footer. This layout has an aft cabin and an aft cockpit and is exceedingly flexible. In normal cruising, it means there are two private cabins in the boat, one forward and one aft. At sea, there is a private cabin aft, but not so far aft that the bunks are unusable in rough weather. In appearance, she is quite traditional and the underbody is full run with attached rudder.

The Formal Survey

Having done a fifteen-minute survey and reached agreement on price with the seller of the boat, the next step is to have her formally surveyed by an individual who is competent to do this work.

Obviously, the broker who is handling your negotiations can’t do the survey: conflict of interest.

Your broker, of necessity, knows who the local surveyors are and keeps a list of their phone numbers, so selection can begin with him. If you feel your broker has dealt with you in a competent and aboveboard manner, you may feel inclined to ask him for a Recommendations for Choosing the Type of Boatspecific recommendation or even let him select the surveyor, in addition to scheduling the haul.

If you would prefer to poke around yourself, his recommendations are a place to start, and below are a few other ideas to help you on your way. Before you leave the broker, however, ask this question: «To whom does the survey have to be satisfactory?»

There is only one answer: to you.

The same thing is true about the surveyor. Here, then, are some suggestions:

- If your broker is also in the new boat business, ask who surveys his trade-ins.

- Refer to the membership list of the National Association of Marine Surveyors (86 Windsor Gate Drive, North Hills, NY 11040).

- Ask a broker from whom you did not buy.

- Ask the manager of the yard or marina where you plan to keep the boat.

- Ask the financing company.

- Ask the insurance company.

- Ask your buddies who are boat owners and have had surveys done.

If you do a few of the above, several things will soon be clear:

- the boat business is a small world;

- everybody knows everybody.

Surveyors are a tiny subset of this microcosm. The same names will keep turning up and the inflections with which they are discussed will enable you to decide who the likeliest is for you. So call and chat with the fellow.

Marine surveying also is not a field for which degrees are conferred or boards issue certificates, so questions about background, years of experience, etc., are very much in order, as are questions about fees, which are usually based on the length of the boat – $8 to $10 per foot currently in the Northeastern United States. Any conversation like this is going to turn up not only specifics, but a lot of incidental information and an overall impression as well; by the end of it, you should be able to decide whether or not this particular man will address himself to your concerns about the boat in a way that will be satisfactory and intelligible to you.

Okay, then, you’ve hired the surveyor. What should you expect Basically, a very thorough and more extensive examination of the areas into which you looked during your fifteen-minute examination of the boat. Having done the fifteen-minute survey yourself, you should have a good idea of what to expect; you will have taken this into account in the price you offered. What you want from the surveyor is an indication of anything surprising.

As a rule, your concerns (and those of the insurance and financing outfits) at this penultimate stage of the game are:

- Is the boat structurally sound?

- Is it suited to your kind of boating?

- How does it stack up against other boats of the same type and age in your general area?

Obviously, these are all questions of judgment and these judgments follow from observations that the surveyor makes when he inspects the boat. The bulk of the survey report, therefore, consists of the data upon which the conclusions rest. You, in assessing the report, need to be satisfied that a sufficiently thorough examination of the boat was made – that enough observations were made to ensure sound deductions.

To avoid oversights and to indicate to you what he has inspected, most surveyors use a checklist. The form varies quite a lot, as does the manner of its organization. Some surveyors arrange things into:

- functional groups (mechanical, plumbing, electrical);

- some group things by their physical location (deck, interior, underbody);

- some use a combination.

The briefest glance through the report will show the system.

In any event, a surveyor works by looking for anomalies and this is what he’ll call attention to in his notes and comments. It’s the exceptions that you’re interested in, too, because these are the things that you’ll probably want to get fixed:

- the valves that don’t work;

- the smoky engine;

- the sag in the deck near the mast step.

These are the items in the data string that lead to the final assessment of the boat and may be clues to larger, underlying problems.

To give you a feel for all this, let’s take an imaginary walk around, on and through a boat, beginning when she is hanging helpless, out of her element, in the slings of the yard crane.

Underbody

Ideally, the underwater part of the boat should be as smooth and fair as an egg. This is rarely the case, of course, due usually to uneven buildup of the anti-fouling bottom paint over the course of the years. Often, the places where the support pads of poppets or cradles touched the hull will be ridged with old paint; this is innocuous and tolerable in a cruising boat.

Other conditions, also detectable by eye, may not be so benign.

Water is a great penetrant and, given time, will work its way under any covering surface and lift it. This lifting shows up as bubbles or blisters, first in the paint and then in the outer layer of fiberglass (the gel coat) itself. The blisters can be any size and can be thinly scattered or densely packed, looking often like a severe rash. Bad cases are rare; light and random scatterings of pea- to quarter-sized bubbles are fairly common. In any case, it’s up to the surveyor to call attention to the condition and decide what, if anything, should be done about it.

Once the visual examination is done, a surveyor will usually examine the underbody aurally by tapping it all over with a mallet. What he is listening for are voids – areas in which air bubbles were trapped when the boat was originally molded. Again, depending upon the size, number, and location of these, a judgment must be made to fix or ignore them.

In the vast majority of boats, neither blisters nor voids are present to a significant degree. Problem areas practically never concern the basic shell of the boat, but rather the appendages and running gear:

- the keel,

- rudder,

- struts,

- propellers,

- shafts.

The most common underwater anomaly by far is worn cutless bearings. This bearing is a rubber-lined tube through which the shaft passes and is located near the propeller end of the shaft to support it. After several years of use, it is natural for the rubber to become worn and for a gap to develop between the shaft and bearing surfaces. Sometimes a shaft will pick up a nylon fishing line and this will severely lacerate the soft lining of the bearing. In any case, the bearing or bearings are looked at and a judgment made. In a sailboat with a solid prop, some play is tolerable; in a sailboat with a folding prop, there should be virtually none.

Shafts, props, struts, and rudders also need to be examined for various kinds of corrosion and mechanical damage, as do the through-hull drain fittings and electronic transducers.

Fin keel sailboats are particularly vulnerable to damage from grounding incidents. The worst damage often occurs not at the point of impact on the lower front corner of the fin, but at the back upper corner where it joins the bottom of the boat, because this part is driven upward when the fin hits. Evidence of a grounding, therefore, means that the surveyor must also look carefully at the area inside the boat that is above the back edge of the keel.

Topsides

The criteria for the topsides of a fiberglass boat are generally the same as for the bottom: they should be smooth and fair (curved in even arcs without lumps, hollows, or flat spots). Their appearance should be appropriate to the age of the vessel, ranging from virtually new to a normal collection of superficial scuffs, scratches, and mars, which any boat is going to acquire from routine use, docking, and anchoring. Past repairs should be holding well and should not be violently obtrusive to the eye. How your boat looks is, after all, important.

Sounding the topsides with a mallet is particularly important if the hull is not simply a laminate of layers of fiberglass cloth, but also contains a central core of balsa wood or synthetic material, as the glass sometimes parts company with the coring. If separation (called «delamination») exists, the surveyor needs to decide whether it should be fixed, watched, or ignored. This judgment will depend upon the extent and location of the delaminated areas.

Deck

While hulls may be cored, virtually all decks are cored. So, again, it’s a case for the surveyor’s hammer and judgment.

In contemplating a fix in either the deck or the topsides, you need to keep in mind the need for artful workmanship. To repair a delaminated area, holes are drilled to the core and new resin or epoxy glue is run in. This binds the surfaces back together all right, but leaves the problem of blending the holes unobtrusively back into the exterior surface; this requires an artful eye and a skillful hand. It is best to defer a fix until a proper job can be done.

After the deck has been sounded, the on-deck equipment (lifelines, winches, stanchions, etc.) needs to be examined and a list made of things that aren’t working or need some sort of attention. In sailboats, common items here are cracked fittings at the ends of the lifelines and loose mooring cleats and chocks. It is also not unusual to discover that a wheel-steered sailboat’s emergency tiller isn’t on board, is difficult to use, or is otherwise unfunctional.

Interior

The interior of a boat contains the structures that stiffen the skin, which is what we’ve been looking at so far. The principal stiffeners are vertical plywood panels, called bulkheads, that divide the boat up into compartments. These panels are attached to the inside of the hull by means of fiberglass tape, which is run along their outside edges and laps from two to six inches onto panel and hull alike. Since the heaviest stresses on this hull/bulkhead connection come from the impact of waves at the bow, a surveyor will usually start there and work his way aft, examining as much of the taping as he can see over and under and around the rest of the cabinetry. This is a slow process, as it means moving cushions, removing drawers, and unloading lockers and closets.

This is also the time in the survey when the toilets and drains and other minor subsystems and their seacocks are checked. If worn cutless bearings are the most common fault in the exterior of boats, frozen (locked up or corroded so that they won’t turn) seacocks are far and away the most common item needing attention in the interior. Seacocks exist so that you can stop the water flow at a through-hull if its hose happens to pop off or otherwise begins to leak. Like fire extinguishers, they really must be ready for use at all times.

Sailboats with deck-stepped masts quite commonly have problems with the interior support structure and this area is sure to be on the surveyor’s checklist. Sometimes the problem is water finding its way through the mast step fastenings into an underdeck wood cross member and softening it. Surprisingly often, though, a subsidence is caused by the fact that there is no continuous, unbroken line of support from the underside of the step to the bottom of the boat. A vertical teak two-by-four will be in place all right, but it will stop at the floor and, lifting a floorboard, the surveyor will find he can put his hand between the top of the keel and the bottom of this column that is supposed to transfer the load of the mast from deck to keel (you may remember hearing this litany before).

Now, obviously, as a surveyor looks through a boat this intimately, he’ll notice a lot of other things – whether the bilge is dirty or clean, the general cleanliness of the head and galley areas, condition of the miscellaneous gear, etc. – from which he will form an opinion about the quality of the general housekeeping and routine maintenance the boat has been given. But let’s stick to the big picture and wrap things up with a look at the power plants, wind, and iron.

Although surveying is a specialized activity, in assessing sails and engines most surveyors have to take the stance of knowledgeable generalists, because both these items are the products of a more intricate and subtle technology than is the Self-Survey Criteria for the Basic Boatbasic boat.

Sails

The parts of a sail that take the wear and tear are the corners and the edges – particularly the back edges, which get chafed by the boom topping lift or the spreaders and shrouds. By looking at these areas and taking a random paw through the body of the sail, a judgment can be made about the type of use and care the sail has had (or hasn’t) and whether it is usable as is or in need of a going-over by a sailmaker. For a boat that is simply going cruising, this is usually sufficient knowledge – the probable condition of the sails being of more moment than their shape (shape in its aerodynamic sense). About this, only a practicing sailmaker could rule and then only by seeing the sails in action on the boat.

Engines

As a general rule, the shortcomings that turn up on survey are not, strictly speaking, due to the engines themselves. Possibly this is due to the fact that, once they are assembled, humans can no longer routinely get their mitts into the engines’ innards. In any case, the things that turn up are usually items such as these:

- Filters and plugs that appear to be overdue for changing.

- Coolant water pumps that leak.

- Hoses and wires that are led close to moving or hot parts of the engine and which are being chafed, scorched, or melted.

- Fuel lines that are made up in a makeshift manner with questionable connectors.

- Fuel tanks of mild steel, which are mounted so that water is held against their outside undersurface.

Obviously, many of these items stem from casual routine maintenance and are flaws in the care of the engine; the poor beast itself is not to blame. Equally obvious is the fact that these things can be spotted without running the engine.

The running trial of the engine in a sailboat can usually be carried out – once the boat is relaunched – at the dock, as it is a rare vessel that is underpowered. A quick way to check, though, is to take the weight of the boat (displacement) in tons and multiply by three. Thus, the dear old Atomic 4 (30 HP) will adequately power a sailboat weighing up to 10 tons, which is about what 40-footers displace.

During the trial, the surveyor expects to see the following:

- Gauges in the normal range.

- Good flow of cooling water from the exhaust.

- Adequate power patently developed.

- Rated RPM reached; cruising RPM maintained.

- No leaks or weeps from engine or exhaust system.

- No Smoke.

Smoke comes in three basic colors – blue, white, and black. It is an infallible sign of ill health and can, in human terms, mean flu or funeral. Most of the time the ailment is non-lethal. A slightly overfilled crank case can cause blue smoke (minor), but so can worn piston rings (major). Black and white smoke are often traceable to props that are too large or too small, respectively. Here again, the surveyor will have to form an opinion and make a recommendation to you.

Once the smoke, so to speak, has cleared and you have the written report from the surveyor, you have to decide if the boat – now seen through the eyes of another – is essentially what you bargained for or if there are things about it that trouble you. In other words, you have to decide if the survey is «satisfactory». If it isn’t, you should make a list of items that you find not satisfactory and discuss them with your broker. Any survey is going to produce a string of comments, observations, and suggestions; many surveyors will conclude their reports with a list of those items they deem most important. You, however, in going through the whole report, may give things a different weighting and come up with another list. Remember, it’s you that has to be satisfied with this purchase. So, if the boat seems a little less desirable after the survey but there are things that can be done to put the glow back, say what they are so that the deal can finally be truly struck and you can get on to the fun of boating.

To better fix this in your mind, I have selected three surveys that appear on the following pages.

Survey One is a bad survey and, obviously, the boat has been badly abused and horribly neglected. The person who bought her was in the market for a reconstruction project, had the skills (and time) necessary, and was able to make a serviceable vessel out of her after about three months of hard, continuous labor.

Survey Two is a mildly alarming survey, but, upon examination, it consists of a collection of items that are fairly readily fixable. It’s of particular interest because it shows that an engine can tell its story even if it can’t be run. As you see from the date and location, the boat had been hauled and laid up for the winter. The price of this boat was negotiated downward, buyer and seller agreeing to split the costs. An eminently reasonable solution, since the buyer was going to enjoy the major benefit of those repairs.

Survey Three reflects an unusually well-loved boat and the items noted are normal and considered part of the routine Technical Recommendations for Inspecting Your Boatmaintenance of the boat.

As a final note, I should say that most surveys are more like Survey Three than the other two. Boat Three is unusual mainly in her degree of cleanliness. Most used fiberglass boats have been very gently used and, therefore, are structurally sound and in need of nothing more than:

- soap,

- water,

- and wax.

Mr. Michael Smith

123 Drury La.

Monhegan, NY 10544

Dear Mr. Smith:

Here is the written report of the survey I did for you of the Waveaway 33 sloop, «Moxie», at your New London yard on Saturday, March 26, 1983.

Identification

- Manufacturer’s Serial №: 303 057.

- Label glassed to hull inside port seat locker indicates construction began July 10, 1972.

- Registration/Documentation №: None seen.

- Hailport: None seen.

Underbody

Procedure: inspect underwater area for smoothness and adhesion of anti-fouling paint, current or past damage from grounding; check struts, props, shafts, thru-hulls, cutless for dezincif ication, crevice corrosion, mechanical damage or excessive wear; pull rudder through full range, check for smoothness and excessive play; sound hull for voids or delaminations. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Salt water trails from hull/keel seam one day after haul indicates keel bolts are leaking. Due to manner of construction, judge only thing to do is plan on dropping keel and rebedding every other season or so. Installation of larger backing plates might help.

- Forward face of skeg and aft edge of rudder blade chewed up; probably due to tangle with mooring chain/cable or similar incident.

- Numerous small spots of «osmotic» penetration of gel coat scattered all over underbody. When punctured (see area around bow), red liquid squirts out; this judged to be salt water colored by «tracer» strands in first layer of mat. Condition judged to be an on-going maintenance item; annoying, but not lethal.

- Area of dry laminate (marked with yellow crayon) should be disced off and faired up prior to launch.

- Long and deep scratch in port side underbody amidships; fair up with epoxy filler.

Topsides

Procedure: inspect for general fairness and evidence of past repairs; sound for voids and delamination; mark for repair any scratches or dings which penetrate the gel coat. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Numerous deep, long scratches, dents, scuffs and dings; only thing for it is to refinish with Awlgrip or similar.

- Transom is just plain ugly; looks like lettering was done with a leaf rake.

- Stern light shines straight down rather than aft.

- Teak toe rail split and loose port side amidships.

Deck

Procedure: sound for evidence of delaminations and mark any for repair; inspect lifelines, stanchions, winches and all fittings generally for excessive wear, breakage or malfunction. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Mild steel bolts in tiller yoke; for on-going directional control, replace with stainless.

- Stern ladder very loosely mounted.

- Cowl missing from port vent at transom.

- Backstay does not lead fair; bears on stern rail.

- One corner of spinnaker pole chock split.

- Delamination:

- Entire port walkway between first and third stanchions.

- Three large areas around port forward lower.

- One dozen small voids (red circles) scattered randomly around; judged as built; not of concern.

- Large broken void starboard side on cabin trunk; should be filled and faired up.

- Forward hatch hinges loose.

- Starboard side stern rail brace loose.

- Port turning block frozen.

Interior

Procedure: in so far as ceiling and liners permit, examine bulkheads and partial bulkheads, chain plate knees, mast step or support structure for soundness and integrity of attachment to hull; check thru-hull valves for function, hull/deck joint for voids or leaks; check toilet and stove for function. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Layered mild steel backing plate for stemhead fitting very corroded, but judged sound.

- Numerous dark trails and patches on liner, shelving and berths port and starboard indicate many leaks from hull/deck joint and toe rail fastenings.

- Aft end of riser on port «V» berth loose.

- Door into head compartment may need trimming for fit; check when boat is afloat.

- Bulkheads at aft end of port and starboard «V» berths loose from headliner.

- Taping break at inboard face of starboard fore and aft bulkhead in head compartment.

- Sole in head compartment warped and lifting in area around keel bolt.

- Formica surface lifting from shelf over hanging locker.

- Sliding panels to locker outboard of head could use trimming for easier fit.

- Toilet: Raritan «Compact» manual unit connected via a Y-valve under forward end of port settee to discharge either overboard or into a 2 gallon plastic jug:

- Y-valve set to discharge into tank.

- Pump and selector feel okay.

- Needs cleaning.

- Shut-off to forward water tank frozen.

- Head sink drain seacock frozen; free up prior to launch in Spring.

- Taping separating port and starboard through much of the boat along lower joins of bulkheads and hull, floor pan and hull; run in new epoxy and draw up with screws as appropriate.

- As built, neither of the two compression columns under the deck-stepped mast run through to the hull; the aft column (which takes most of the load) has shifted aft and torn the main bulkhead from its deck and hull attachments; remove mast, re-align bulkhead and column, insert chocks between bottom of boat and under-surf aces of columns, refasten bulkhead.

- Backing block over port settee leaking.

- Two main cabin fire extinguishers need refill/replacement.

- Stove: Homestrand Model 206 two-burner, recessed, gimballed, pressure alcohol unit with cutting board cover:

- Everything badly corroded; dirty.

- Pump not working.

- Gimbal latch frozen.

- Needs complete reconditioning.

- Trim inboard of stove split.

- Sliding panels missing from locker outboard of stove.

- Galley pump feels shot.

- Veneer lifting on outboard back corner of chart table lid.

Rig

Procedure: examine spars for excessive wear and tear; check terminals for cracks, rigging for broken strands, sheaves for free running, running rigging for excessive wear. If boat is rigged, indicate manner in which upper rig checked; check turnbuckles for clevis and cotter pins; examine visible parts of chain plates for excessive wear, broken welds or cracks. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Mast:

- Upper area inspected with 20X telescope.

- Jib halyard sheaves appear to be riding on a long pin or bolt whose ends are taped over with duct tape.

- Connectors for antenna and wind instruments hanging loose and unsecured.

- Otherwise, normal superficial wear and tear.

- Boom:

- Rather corroded, but appears serviceable.

- Mainsheet pretty ratty.

- Spinnaker pole:

- Heavy, but superficial wear and tear.

Sails

Procedure: inspect corners, edges (as feasible) and random sample of bunt as working conditions permit. If vessel is rigged and wind conditions permit, unfurl roller furling headsails. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Eleven bags counted, but sails not inspected. Little bit I saw of the main looked like it could use a wash and going over by a sailmaker.

Engine

Procedure: note make, model, type and serial number (if possible to locate and read); check beds for attachment to hull, mounts for integrity; visually inspect for signs of leaks and weeps; check vital fluids for level and condition; start engine, check gauges for function, note readings after warm-up; try controls, check that normal power is patently developed, monitor stuffing box for proper level of weeping and any indication of misalignment; watch for smoke and any leaks or weeps from engine; recheck all vital fluids after shut-down. If visible, check fuel tank material and appearance, manner of tie-down, location of fill and take-off spuds, shut-offs and type of fuel line. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Universal «Atomic 4» 4 cylinder, 4 cycle, raw-water cooled gasoline; model and serial number illegible:

- Like everything else on vessel, looks completely neglected.

- Hour meter shows 885.

- Condition of top of block and exhaust manifold indicate engine overheated at some time in the past.

- Condition of top of block indicates something may be weeping excessively now.

- Starter motor has been replaced; this, plus other indications elsewhere, may mean boat was flooded at some time in the past.

- Oil full, brown (normal).

- Alternator belt very loose.

- Salt water pump grease cup frozen.

- Salt water pump probably leaking.

- Fuel line leaking at pump filter.

- Glass bowl at pump filter should be replaced with metal.

- Shift lever frozen.

- Starts readily enough, but with great cloud of black soot.

- Cooling water flow judged adequate.

- After warm-up, gauges read:

- Temperature: 90° (probably gauge, as thermostat housing feels normal to touch).

- Oil pressure: №15 (very low; accords with smoke noted below).

- Amps: +25 (high; check regulator).

- After warm-up, black smoke changes to generous cloud of blue.

- The dear old thing is trying, but mercy is reccommended.

- Exhaust system:

- Appears quite elderly; very corroded.

- Hot part should be wrapped in asbestos.

- Fuel tank: cylindrical monel unit (est. 20 gallons) strapped athwartships to wood chocks aft of engine.

- No signs of leaks or weeps.

- No perceptible movement.

- Line from filter on starboard bulkhead to engine is copper tube; should have section of jacketed flexible high-pressure hose with flared or compression fittings.

- Check for water shows traces at bottom of tank; add some «dry gas».

- Blower switch in port seat locker, but no blower.

- Vent hose has fallen off starboard transom vent.

Batteries

Procedure: check manner of installation; note type and make (if possible to read labels); estimate age; check each cell with hydrometer. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Two Exide M-84 automotive units in plywood compartment at foot of companionway ladder; estimated two to three seasons old.

- Addition of acid-proof cases would be a good idea.

- Hydrometer check indicates two serviceable units at 50 % state of charge.

Electrical

Procedure: check all items for function. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Light at chart table not working.

- Powering light not working.

- Deck light not working.

- Port running light not working.

Electronics

Procedure: list units, model and serial numbers (if legible without demounting); check for function (if practicable):

- Ray Jefferson 1225 VHF-FM; serial №C04832; okay.

- Kenyon KL 100 log; Serial №C4104; could not check function.

- Kenyon AW 300 analog apparent wind indicator; Serial №23135; okay.

- Kenyon KS 300 analog knotmeter; Serial №14144; could not check function.

- Kenyon WS 100 analog anemometer; Serial №23126; okay.

- Seafarer MK III neon flasher depth finder on swing bracket:

- Transducer wire broken.

- No battery or external power supply.

- Danforth bulkhead-mounted compass; Serial №H42551.

- Dome and fluid oxidized; card unreadable.

Essential Items of Repair/Maintenance

Review notes and list items judged necessary to repair or set right prior to using boat:

- Rebed keel; install largest and thickest backing possible for bolts.

- Dress up the skeg and rudder; disc out and reglass area of dry laminate in underbody.

- Aim stern light correctly.

- Refasten stern ladder.

- Repair delaminated port walkway and area around port lower chain plate.

- Recondition stove.

- Redo the mast support structure.

- Repair/replace galley pump.

- Check out jig halyard sheave pin.

- Replace main sheet.

- Replace engine.

- Fix port running, steaming light.

- Hook up depth finder.

Recommendations per National Fire Protection Association

- Carry three fire extinguishers – one in forward cabin, one in main cabin, one in cockpit seat locker. (NFPA 302-49; Table 9)

- Install a blower. (NFPA 302-6; 132)

Conclusion

In my opinion, once the deck delaminations are repaired, the mast supports redone and the keel reset, «Moxie» will be structurally sound enough for coastal cruising and racing in the conditions generally prevailing along the United States East Coast during the normal boating season.

Her condition, as I found her, can only be described as desperate and appeared the result of many years of continual hard use and virtually no routine maintenance or general housekeeping.

It is the intent of this report to provide an unbiased judgment of the vessel and her equipment in the light of her intended use. A conscientious effort was made to inspect the entire vessel. However, since this report is based on a visual examination of the vessel, it is not rendered as a warranty or guarantee of the performance or condition of this vessel or her machinery, but solely as my opinion based on what I observed. Defects not discoverable without opening up or removing sheathing, joinerywork, fittings, tanks and/or disassembling machinery or other parts of the boat are not covered by this survey.

Sincerely _____________________ signature

Hewitt Schlereth

Mr. Rbt. Perry

131 E. Prospect Ave.

Salem, NY 10553

Dear Mr. Perry:

Here is the written report of the pre-purchase survey I did for you of the New Way 30 sloop, «Baby’s Legacy», at Greenpoint Yacht Yard, Westport, Connecticut, on Thursday March 10, 1983.

Identification

- Manufacturer’s Serial №: 143 (on plate in cockpit).

- As of November, 1972, boats built for United States Market are required to have twelve-digit serial number molded into transom. Query builder regarding model year.

- Registration №: NY 9742 DM.

- Hailport: Larchraont, NY.

Underbody

Procedure: inspect underwater area for smoothness and adhesion of anti-fouling paint, current or past damage from grounding; check struts, props, shafts, thru-hulls cutless for dezincif ication, crevice corrosion, mechanical damage or excessive wear; pull rudder through full range, check for smoothness and excessive play; sound hull for voids or delaminations. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Play in rudder judged within normal range for this model; not of concern.

- Knuckle and aft upper corner of fin keel should have application of new glass to repair minor damage from past grounding(s).

- Bottom paint applied with a brush; generally smooth and adhering well; needs only routine preparation prior to fresh coat in the Spring.

- Several spots on keel where filler is lifting; could use routine attention.

* Cutless bearing and propeller shaft quite worn; best replace.

Topsides

Procedure: inspect for general fairness and evidence of past repairs; sound for voids and delamination ; mark for repair any scratches or dings which penetrate the gel coat. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Usual collection of superficial scuffs, scratches, dings and mars to be expected in a used boat; routine compounding and waxing should maintain satisfactory appearance.

- Old repair to nick at port transom edge a little crude, but holding well.

- Vinyl rail could use routine cleaning.

- Vinyl rail has been cut away around stem, probably due to interference with mooring rodes; doesn’t offend my sense of esthetics, but you may feel differently.

Deck

Procedure: sound for evidence of delaminations and mark any for repair; inspect lifelines, stanchions, winches and all fittings generally for excessive wear, breakage or malfunction. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Cover plate for bilge pump missing.

- Small amounts of crazing scattered randomly around deck and cockpit; judged within normal range; not of concern.

- Forward end of starboard handrail could use tightening.

- Seam at join of deck and hull on port side of area where vinyl rail removed should be filled with GE 5200 or equivalent; may be source of some of the water entering rode locker (noted later in Interior section of this report).

Interior

Procedure: in so far as ceiling and liners permit, examine bulkheads and partial bulkheads, chain plate knees, mast step or support structure for soundness and integrity of attachment to hull; check thru-hull valves for function, hull/deck joint for voids or leaks; check toilet and stove for function. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Pulpit-base and bow-chock fastenings leaking into rode locker; lift and rebed when feasible.

- Filler material at base of stem stiffener has pulled away from rode locker bulkhead; not judged of concern.

- Molding around forward hatch a little chewed up from relocating lift arm.

- Wing nut on lift arm frozen, but arm serviceable as is.

- Toilet: Wilcox-Crittenden «Head-Mate» manual unit connected to discharge overboard through a seacock located under aft end of port «V» berth.

- Pump feels normal; no signs of excessive leaks or weeps.

- Head door may need trimming for fit; check when boat is launched and rigged.

- Velcro peeling off head compartment portholes.

- Hinges loose at aft end of port settee extension/seat flap.

- Stove: Horaestrand Model 206 recessed, non-gimballed, two-burner unit with hinged, stainless steel cover:

- Tank holds pressure; fuel flow normal.

- Bilge somewhat oily.

- Bilge pump pick-up line could use bronze strainer to ensure maximum drainage of shallow bilge.

- Chart table hold-back hook broken.

- Taping separation at divider in lazarette; not judged of concern.

* Discharge seacock frozen.

* Intake seacock frozen (under forward end of port settee).

* Head sink drain gate valve frozen.

Rig

Procedure: examine spars for excessive wear and tear; check terminals for cracks, rigging for broken strands, sheaves for free running, running rigging for excessive wear. If boat is rigged, indicate manner in which upper rig checked; check turnbuckles for clevis and cotter pins; examine visible parts of chain plates for excessive wear, broken welds or cracks. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Mast:

- Normal superficial wear and tear.

- Boom:

- Tack shackle not on boom.

- Otherwise, normal superficial wear and tear.

- Spinnaker Pole:

- Otherwise, normal superficial wear and tear.

- * One piston frozen.

Sails

Procedure: inspect corners, edges (as feasible) and random sample of bunt as working conditions permit. List comments, observations, suggestions:

- Main: Ulraer – normal use indicated; good.

- Mainsail Cover: Ulmer – label tattered; otherwise, minor normal wear and tear.

- Roller Furling Genoa: Ulmer – normal use indicated; good.

- Roller Furling Genoa: Hild – older than above, but judged serviceable.

- Jib: Hild – meat hooks in one pennant eye; otherwise, ditto above.

- Spinnaker: Ratsey – normal use indicated; good.

- Awning – appears virtually unused.

* Heavy-Weather Jib: Ratsey – little use indicated; still has piston hanks, so will not work with roller furler.

Engine

- Medalist Industries «Universal Atomic 4» 4 cylinder, 4 cycle, raw-water cooled gasoline; Model UJ; Serial №176833.