Hull Design Choices play a crucial role in determining a vessel’s performance and stability in the water. Whether you opt for planing hulls that excel in speed or displacement hulls designed for efficiency at lower speeds, each type has unique benefits. Semi-displacement hulls offer a blend of both, making them versatile for varying conditions.

The materials used, such as wood, fiberglass, or composites, further influence durability and maintenance needs. Engine selections, including gas or diesel options, also depend on the chosen hull design. Understanding these elements is essential for making informed decisions tailored to your boating needs.

Hull Designs

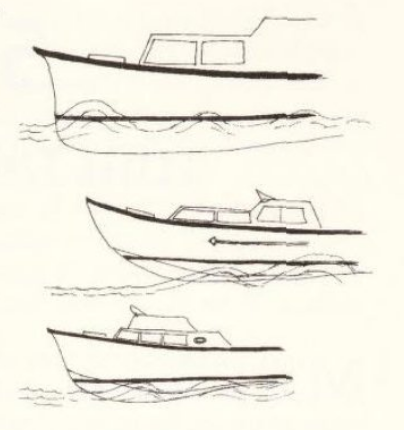

More than any other single factor, the hull design of a powerboat dictates the type of boating you do. While there are hundreds of variations on each theme, hull designs in powerboats consist of three basic varieties:

- planing;

- displacement;

- and semi-displacement hulls.

Planing Hulls

Planing hulls are designed to cause much of the boat to lift above the surface as the vessel’s speed increases. Since air offers less resistance to travel than does water, less wetted surfaces reduce drag on the hull. Ski boats, racing craft, and many trailerable weekend cruisers rely on the planing principle to achieve maximum possible speed. Planing hulls use high-horsepower, high-rpm engines (frequently gasoline burning). They quite commonly incorporate a series of adjustable underwater flaps known as trim tabs. Trim tabs are used to level out and control the ride of a planing boat as it flies through the water’s surface. In the search for greater lift and less resistance, manufacturers are constantly experimenting with combinations of steps, ridges, reverse curves, and strategically placed channels below the waterlines of Basic Hull, Keel, and Rudder Shapesplaning hulls. For boaters requiring maximum possible speed, a planing hull allows a boat to cover the greatest distance in a minimum of time.

The disadvantages of of planing hulls include high fuel consumption, high engine noise levels, and a tendency to bounce and slam across the waves in seas any heavier than a light to moderate chop. Boaters operating a boat at planing speeds learn to keep a sharp eye for logs or debris floating in the water. A log that would simply make an alarming thump against the hull at 8 knots might very easily hole a boat if struck at 20 knots. The characteristics of a planing hull can, in some designs, actually make the craft a little less seaworthy at slower speeds, when the vessel is not up on plane. Planing hull boaters also keep a sharp eye on the weather and use the higher speed of their vessels to get to shelter quickly in the event of rough weather.

There is a practical limit to how large a superstructure can be placed on a planing hull without resorting to multi-hull configurations (such as a catamaran) to support the weight, or having to use monster engines to get an extra heavy vessel up on plane. Because of the generally shallower draft, planing hull vessels tend to be affected more by winds than by currents when maneuvering at slow speeds (as when navigating through a marina or docking).

Displacement Hulls

Displacement hulls are typically found on the largest, most seaworthy vessels and rarely, if ever, on a trailer boat. Displacement hulls feature deep drafts, usually with a full-length keel to improve directional stability. The transom on a displacement hull is typically completely above the normal waterline, thereby reducing the effect of strong following seas that might create steering difficulty or even broaching (turning sideways) in heavy weather. Displacement hulls tend to plow through rather than bounce over wakes and choppy seas. They can support more superstructure above the waterline than any other single-hull design, and are most commonly powered by diesel engines that emphasize high torque output at a lower rpm. As the construction of a displacement hull requires a larger amount of materials and labor, it is more expensive than a planing or semi-displacement configuration on a vessel of the same length. The ride of a displacement hull is more stable than the ride of a planing hull, and it is easier to move around the boat and hold a conversation while underway. Displacement hulls often achieve impressive fuel economy when considered from a gallons-per-hour perspective, but will be the slowest hull design in any given size category due to the drag created by the large mass of hull in the water.

Hull speed. Naval architects refer to hull speed when they discuss the speed potential of a boat’s design. It is computed by multiplying 1,35 times the square root of the boat’s waterline. Hull speed is the speed at which the hull design itself begins to resist traveling any faster. It can be as little as 5 or 6 knots on a displacement-hull pleasure craft, and it would be unusual to have a displacement hull speed of over 10 or 11. It is possible to push a vessel beyond hull speed by equipping it with monster engines and leaning heavily on the throttle, but most old salts (who seem to comprise a high percentage of the boaters gravitating to a displacement-hull craft) are likely to enjoy the passage as much as the arrival at a destination. They are willing to accept the slowest type of hull by virtue of its superior sea-keeping abilities. Single engines are very common on displacement hulls. Unless adorned with a mammoth superstructure, displacement hulls are more affected by tide or current than by normal winds when cruising or docking.

Semi-Ddisplacement Hulls

Semi-displacement hulls are fairly common in medium-sized powerboats of 30-45 feet. The design goal of a semi-displacement hull is to incorporate some of the speed of planing hulls with some of the seaworthiness of displacement varieties. Depending on design variations, some semi-displacement hulls behave more like a true planing or displacement craft than others. Some semi-displacement hulls may even have trim tabs, while others may feature a modified keel design. Many How To Choose Your First Powerboatsemi-displacement hulls will have small steps built into them like planing hulls, to encourage greater lift as speeds increase. At the upper end of the speed range, some semi-displacement hulls may actually put little or none of the hull clear of the water. But in general the waterline will move down the hull enough to significantly reduce wetted surface and thereby reduce aquatic resistance.

Semi-displacement hulls are powered by either gasoline or diesel engines, with twin-engine configurations common. With large gasoline engines, semi-displacement hulls can achieve impressive speeds of 25 knots or more, but skippers who operate larger vessels at such speeds will spend a significant portion of their time, not to mention their family fortune, at the fuel dock. Semi-displacement hulls are a good choice for boaters who feel the need to break the 9-knot barrier, but want a larger, more open-water boat than a true planing hull.

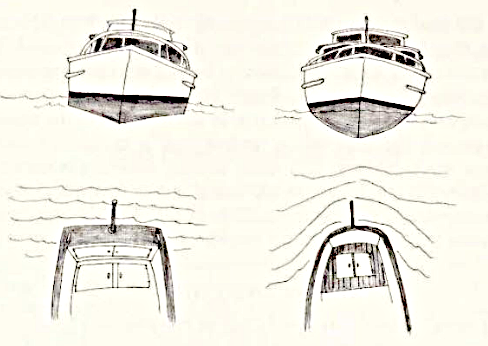

Bows

The design of a boat’s bow has a great effect on its ability to either achieve maximum speed or withstand heavy sea conditions, Boats built for speed will feature a bow with as little wind resistance as possible, often fairly low to the water. While making the boat more aerodynamic, such a design does little to keep the deck dry when splashing through a large wall of water. A vessel with a higher bow, flaring outward above the waterline, is more suited to absorb the shock of larger waves or wakes, and will have a tendency to direct much of the spray away from the boat when settling into a trough between waves, With displacement hulls, special attention is paid to designing an entry angle in the hull shape to allow the boat to make forward progress with as little initial water resistance as possible.

Sterns and Chines

Two other important aspects of hull design that bear on a boat’s handling characteristics are whether the boat has a hard or soft chine, and the shape of the stern. The chine is where the boat’s side meets the bottom. A hard chine has a definite angled or corner like appearance, and creates a flat plane of resistance to help control rolling motion when the hull is subjected to a beam sea. A soft chine has a more rounded, bowl-like shape that tends to continue to curve outward above the normal waterline. As a soft-chine boat rolls to either side, it relies on the increasing amount of wetted surface to create the buoyancy to help right the boat again. Sailboats are the epitome of a soft chine design. A hard chine will provide more resistance to rolling in the light to moderate seas prevailing when most pleasure boaters should venture out, but a seriously designed soft-chined craft with a low center of gravity might have its advantages in heavy storm conditions.

The shape of the stern dictates how much effect a following sea has on a boat’s steering and stability underway. Most sterns on modern powerboats feature large, flat transoms to allow greater room in cockpits and aft cabins – creating a little «more boat for the buck» from many perspectives. These large transoms often have square corners which tend to catch a following sea. The result is that the stern gets pushed to either starboard or port and steering corrections must be made to stay on course and to avoid broaching into the oncoming waves. A stern with a round shape or at least rounded corners allows following seas to pass under the transom with less effect on the boat’s course and steering.

Free Local Advice

When pondering options of hull design (and most other nautical subjects as well), boat owners can be an excellent resource. Boaters you know will normally be happy to share their opinions about the advantages and disadvantages of their particular boats. Ask specific questions about how their boats handle in the conditions common to the local cruising area. Don’t know any boaters? Not a problem. By heading down to the local dock and opening a conversation with a compliment about how great a boat looks, it’s easy to strike up conversations with the majority of boaters. They never tire of the opportunity to pontificate on the particulars of their nautical pride and joy.

Hull Materials

Historically, boats have been made from any number of materials including:

- leather;

- steel;

- cement;

- aluminum;

- reeds;

- tree bark;

- bamboo;

- every type of wood (with the possible exception of petrified);

- plywood;

- and fiber-glass

During the last half of the 20th century, the construction of pleasure boats changed from almost exclusively wood to almost exclusively fiberglass. Shoppers looking at new boats will see an all-fiberglass array except for the products of a few custom or semi-custom builders. When shopping for an older boat, you will find both wood and fiberglass options, with wooden boats being either traditional plank- or plywood-style construction.

Pros and Cons of Wood

Simply because fiberglass technology is newer does not mean it is therefore superior in every aspect to wood. Wooden boat aficionados insist that wood is somehow «homier and warmer» than fiberglass, and many feel that a wooden hull absorbs engine vibrations better to create a quieter boat as well. Builders of fiberglass boats often rely on wooden cabin interiors and exterior trim pieces to increase the charm of their vessels (while owners of wooden boats are not usually seen rushing out to acquire plastic trim pieces to dress up their craft). Wood is an organic material, subject to rot and decay. Fastidious maintenance will control or postpone the rotting process, but it cannot be eliminated entirely. Wooden boats operated in saltwater tend to maintain the integrity of the wood in their hull longer than freshwater wood boats, due to the preservative qualities of sea salt. Some fresh-water wooden boaters have been known to keep a little rock salt in the bilge in an attempt to create the same preservative effect. Traditionally constructed wooden hulls incorporate a number of planks fastened with screws to underlying ribs. When a section of planking or even a rib begins to get soft from rot and decay it is possible to partially dismantle a wooden hull and replace the affected portions. Every so often a wooden-planked hull must be re-fastened in order to maintain structural integrity, with the screws used to hold the planking to the ribs being completely replaced. Wood in the marine environment must be protected by either paint or varnish to repel rot-promoting moisture, and this protective coating must be relentlessly maintained and renewed.

Beware of «Wood Boat-itis». Wooden boats are typically older than comparable fiberglass models and some large, old wooden boats can be available for purchase at what seems to be a bargain price. A prudent shopper will look past the «Wow!» factor at least far enough to realize that maintenance costs, in time and money, on a 20- to 50-year-old wooden hull are a significant factor. Some disclosures by sellers may mean little to an inexperienced boat buyer with palpitating heart and dollar signs in his or her eyes – and who might perhaps react, «So what if it needs to be hauled out and completely refastened, whatever that means. This boat’s twice as big as anything else we’ve been able to consider buying!»

Characteristics of Fiberglass

When introduced, fiberglass was touted as a nearly miraculous boat-building material. Here at last was a material which could be formed into any number of curved surfaces, had high structural integrity, and was not subject to rot and decay. As fiberglass boats are now commonplace and have aged, some limitations have become apparent. Fiberglass boats are constructed by sandwiching together many layers of fiberglass cloth impregnated with resin to form a solid, plastic-like structure. As a boat ages, it is not uncommon for the fiberglass to delaminate and/or blister. Delamination can be cured by drilling into the affected area of small sections, injecting some resin-type compounds formulated for such repairs, and clamping the material back together until cured and resecured.

Blisters. On fiberglass boats, blisters can form on the outside of the hull below the waterline. Most blisters are gelcoat blisters which bubble up under the smooth upper layer of the fiberglass sandwich when water chemically reacts with certain elements of the fiberglass resin. Some hull experts advise that so long as a blister is confined to the gelcoat layer, it can be safely ignored. Another school of thought opines that any blistering must be dealt with immediately and decisively. Blisters can be cured by hauling the boat, grinding down the blister, drying the hull, filling, fairing, and re-gelcoating the affected area. The drying process can be lengthy, and a boat can be laid up for several weeks, resulting in a whopping yard bill.

Maintaining the Appearance of Fiberglass. The smooth, shiny gelcoat finish on a new boat must be cleaned and waxed regularly to prevent oxidization. On older Manufacturing of Fiberglass Boats and Design Featuresfiberglass boats where the gelcoat has been allowed to become chalky to the point of no return, painting the boat with a top-quality yacht enamel is the only method to restore the appearance; and painting a 36-foot boat can cost as much as purchasing an economy car. Some manufacturers of upper-end yachts who can utilize virtually «perfect» molds actually paint the hulls at the time of initial construction rather than rely on gelcoat to create and maintain the beauty of their high-dollar product.

Plywood and Fiberglass Composites

Some boats are built with plywood covered with fiberglass, and some boats with fiberglass hulls have cabin structures built this way. Experience has shown that this combination is often more trouble prone than all-wood or all-fiberglass configurations. The hull of a boat flexes slightly when pounding through a head sea. It also expands or contracts with exposure to heat or moisture, Dissimilar materials react differently. When dissimilar materials are fastened together, internal stresses develop as a result. Plywood can begin to delaminate beneath the fiberglass. Any water trapped between the wood and the fiberglass layers will accelerate the process. Fiberglass-over-wood superstructures have been known to keep boat owners busy chasing rainwater leaks which can be difficult to find and cosmetically or even structurally damaging. For most boaters, all-wood or all-fiberglass construction is less prone to trouble than fiberglass bonded to plywood.

Engine Choices

One Engine or Two?

On most boats under 32 feet there is no debate on this issue. Small boats are typically built with only a single engine or in some cases no engine at all (leaving it up to the purchaser to supply an outboard power plant). Small single-engine boats are commonly an inboard/outboard design with the engine mounted below deck at the stern of the vessel connecting to a drive mechanism mounted on the transom. Steering is accomplished by turning the drive unit to starboard or port while underway, to power the stern in the opposite direction. Owners of such boats often report experiencing as many problems with the out-drive as with the engine itself, with comparable costs for maintenance and repair. By about 30 feet, nearly every manufacturer switches to an inboard-mounted engine and a fixed propeller, with steering accomplished by a movable rudder. Occasionally at about 32 feet and commonly at 36 feet and above, one of the decisions a boat buyer will con- sider is whether to select a boat with a single or dual engines.

Single-Engine Advantages. Single-engine vessels are less costly and time consuming to maintain than twin-engine, consuming fewer:

- oil filters;

- zincs;

- hoses;

- belts;

- starters;

- alternators, etc. (not to mention less lubricating oil, gasoline, or diesel).

In single-engine boats the engine is in the center of the hull. Since most hulls are deepest in the middle, the engine can be set a little lower in relationship to the waterline than an installation of two engines mounted equidistant from the centerline. Setting the engine lower can result in a more favorable angle at which the drive shaft protrudes through the hull, increasing propeller efficiency. An engine placed lower in the bilge may also improve balance and ballast characteristics of a boat. A single engine in the center of the hull can allow better access to both the starboard and port sides of the engine to facilitate routine servicing. And if it follows that an item more easily serviced will be serviced more often, a single-engine installation has a notable advantage in this respect. Single-engine installations achieve the best fuel economy. A single engine is often used in conjunction with an auxiliary engine that drives a generator and in some cases can be used to turn the prop shaft and allow a slow return to harbor, should the main engine fail. The disadvantages of a single engine include reduced close-quarters maneuverability (requiring the development of some docking and boat-handling skills unique to single-engine skippers) and the reliance on a single power plant for motive power.

Why Twin Engines Are Popular. Redundancy is a major safety factor on a boat, especially a vessel operating far offshore. A prudent skipper has a contingency plan to deal with the failure of any major system on board. Nothing could be more redundant than an extra engine with which to limp back to the dock in case the other engine should fail. Single-engine boaters achieve a measure of redundancy by keeping an adequate supply of spare parts (rubber v-belts, raw-water pump impellers, spark plugs, distributor cap and rotor, etc.) aboard to effect emergency repairs of common failures at sea. Boaters should keep an adequate selection of tools and spare parts aboard a boat at all times and develop an understanding of elementary mechanics, but single-engine boaters must be particularly prepared to make minor repairs while underway. Some diesel engine fans could argue that a single diesel engine is as reliable as two gasoline engines, but even if true, two diesel engines would be more reliable yet.

Adding a second engine offers a few advantages beyond simply having spare propulsion potential. A boat with twin engines will usually achieve greater speed than the same hull with a single screw, but in practical terms the speed will never double. The weight of the second engine will cause the hull to settle a little deeper in the water, increasing the wetted surface and creating additional drag. The concept of hull speed applies, regardless of the number of engines, and a boat with displacement hull characteristics that might cruise at 9 knots with a single engine will often do no more than 11 or 12 knots with twin engines while consuming twice the fuel per hour. A second engine will be of no particular advantage under many of the conditions that lead to mechanical failure on a boat. A boater out of fuel (or with contaminated fuel) or a boater with dead batteries will be just as stuck with two engines as with one.

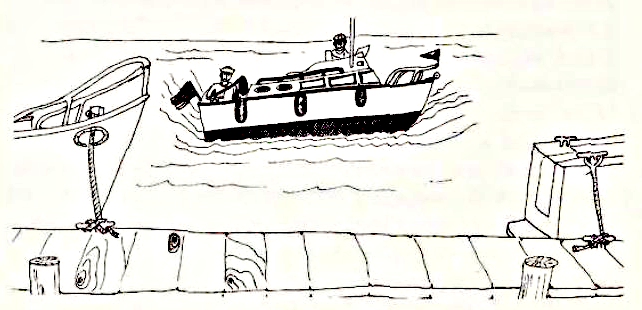

Maneuverability. For many boaters, the primary advantage of twin engines is the additional flexibility of close-quarters movement when docking. With one engine in forward and the other in reverse, it is possible to turn a boat on the spot. Without the addition of a bow thruster even the most highly skilled single-engine boater would have a difficult time duplicating the maneuvers of the average twin-engine operator. Should the hydraulic or mechanical steering system fail (a very rare occurrence), a twin-engine boat can steer by adjusting the speed and the direction of the engines. Twin-engine boats can be steered more easily in reverse than a single-engine vessel as well.

Bow and Stern Thrusters. Single-engine craft that are frequently operated in crowded conditions such as busy marinas and locks, or occasionally operated by a single individual without benefit of a deck crew, will benefit from the addition of a bow thruster. A bow thruster consists of a single, reversible propeller mounted athwartship below the waterline in a tunnel running through the bow, or two propellers with one facing star-board and the other port. On boats under 40 feet, most bow thrusters are electrically driven, while on larger vessels hydraulic units are more common. The bow thruster’s function is to move the bow of the vessel to port or starboard independently of any influence from the prop and rudder in the stern. When docking or undocking either in windy conditions or when single handed, a bow thruster can help a boater avoid some embarrassing moments.

Read also: Stern Gear – Technical Recommendations for Inspection and Maintenance

In addition to, or sometimes instead of a bow thruster, many boaters have installed stern thrusters. A stern thruster operates under the same principle as a bow thruster, but mounted in the stern. It pushes the stern to starboard or port without any of the forward or reverse momentum which would result from using the rudder and prop. With both bow and stern thrusters aboard, a single-engine boater with the benefit of a little practice can practically move a vessel side-ways into or out of a crowded dock.

almost sideways into a slip

Cost and Resale. A factor that cannot be overlooked is the effect on purchase cost and resale value of a second engine. New diesel engines typically sell for prices that represent many months’ income for most boat owners, and gasoline engines can be costly as well. A second engine could make a sizable difference in the monthly boat payment, requiring other compromises in order to make a boat affordable. Some of the cost of a second engine will be recovered when and if the boat is resold, as used twin-engine boats also bring more dollars than similarly sized and equipped used single-engine vessels.

Gas or Diesel?

When shopping for a small day cruiser or runabout, it is unusual to see anything other than gasoline engines. Boats in the 50-foot and over range will almost certainly be powered by diesel. Between 26 and 50 feet, the choices include both gasoline- and diesel-powered boats, with many manufacturers offering gasoline engines as standard equipment and charging extra for diesel engines as an optional upgrade.

Gas Engine Characteristics. Gasoline engines typically operate at higher rpms than diesels, which can be desirable when the function of the engine is to turn a propeller. By virtue of these higher rpms as well as a much lighter weight, gasoline engines will often achieve greater speed than diesel in the same hull. Most boaters drive gasoline-powered cars or trucks, so there is something comfortable and familiar about the concept of a gasoline engine. In the event of mechanical problems a boater would perhaps feel a little more comfortable attempting to troubleshoot the situation. Gasoline engines are much cheaper to buy, new or used, than diesels. The cost advantage is offset by the much shorter life expectancy of gasoline engines. Twenty-five hundred hours on marine engines is equivalent to operating a vehicle on land for 150 000 miles at 60 mph uphill. A gasoline engine with that many hours could soon be a candidate for replacement or rebuilding. Prudent skippers will overhaul a gasoline engine at even fewer hours for safety and reliability or because some mechanical bad luck has befallen it. While there is no scientifically established standard for the number of engine hours a boater will accumulate in a year, 150 to 400 engine hours covers the range of annual usage for most weekend and vacation boaters.