Marine Sanitation Systems play a crucial role in maintaining hygiene and efficiency on board vessels. These systems include Type I and Type III sanitation solutions, designed to handle waste in various marine environments. High-tech marine toilets and sanitation hoses ensure proper waste management, while freshwater supply systems guarantee access to clean water.

The management of gray water and its effective disposal is essential to prevent pollution. Understanding tank capacity, pressure pumps, and dockside connections is vital for optimal operations. By prioritizing these systems, boat operators can enhance comfort and ensure compliance with environmental standards.

When Nature Calls

While still below decks, the opportunity is ripe (hopefully not too ripe!) to evaluate the boat’s sewage system. Not so many years ago the sewage system on a boat was a pretty simple affair: one simply flushed the head by pumping the contents overboard. Out of sight, out of mind. In our more enlightened modern times, the cleanliness of our waterways has become increasingly emphasized, and there is no group who will benefit more from cleaner, less-contaminated water than recreational boaters. Soapy water from sinks and showers may still be drained directly overboard in most localities. Water containing solid or liquid human waste cannot be pumped out without proper sterilization treatment, unless a vessel is more than three miles from shore, and then only in the open ocean. (Dumping sewage overboard three and a half miles from shore in a seven-mile-wide bay or estuary will leave a boater liable for fines which could exceed the purchase price of a modest boat).

Type I and Type III Sanitation Systems

There are two approaches to the sewage problem: sewage is either treated in a Coast Guard-approved sterilization device and then pumped overboard or is stored aboard the boat in a holding tank which will eventually be emptied at a designated pump-out facility connected to a shoreside Complete Guide to Below Deck Sailboat Systems: Ventilation, Marine Heads, Water Systems and moresewage treatment system. Most boats with a certified treatment system will still utilize a holding tank to contain treated waste awaiting pump out, for those occasions when a boater is anchored in a crowded harbor and would just as soon not send the contents of the head (not withstanding proper disinfection) floating past the other boats anchored there. The certified treat-and-release systems are known as Type I systems, while the holding-tank-only approach is known as a Type III. Technically speaking, waste treated in a Type I system and then stored in Type III holding tank becomes Type III material and should be disposed at a dock-side pump out, since bacteria can re-form as the waste is held in the tank.

Type I. Two commonly available Type I methods are the acid bath and the boiler. An acid-bath system uses the salt in seawater (or salt from a salt tank when operating in freshwater) and electrical current to create hypochlorous acid. The sewage is then soaked in the acid for a few minutes until all traces of fecal coliform bacteria have been eliminated and is then directed either overboard or into a holding tank for more discreet disposal at a later time. The boiler systems don’t actually boil the sewage, but they do raise the temperature of the stuff to a point where the bacteria cannot survive. Both systems use a large amount of 12-volt amperage when operating, and it can be advisable to run an engine or generator while processing waste to ease the load on the batteries.

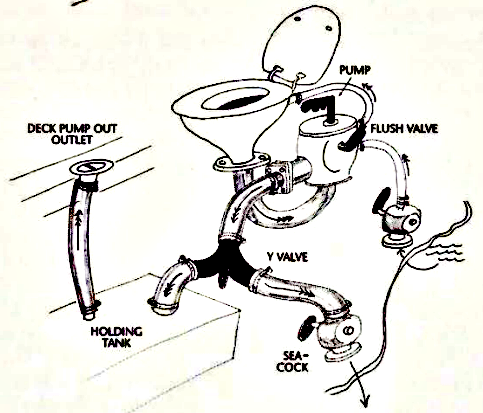

Type III Systems and Y valves. Type III systems usually incorporate a Y valve, which directs sewage either directly overboard where legal or into the holding tank. The position of the Y valve is one of the items often examined when a boat operating less than three miles offshore is boarded by the Coast Guard for a routine inspection. The Coast Guard will expect the valve to be wired or zip-tied into a position whereby waste can only flow to the holding tank. When full, Type III systems are emptied at pump-out facilities which are becoming common at fuel docks and marinas.

A deck fitting with a hose connected to the holding tank will facilitate pump out and eliminate the fairly unpleasant task of dragging the pump-out suction hose down into the bilge and manually opening an access port on the tank itself. On an extended offshore voyage in unrestricted waters, a Type III system may be legally emptied by onboard pumps moving the sewage directly overboard. The two most common pumps are the electric macerator style or a manual diaphragm-type unit.

Holding-Tank Capacity. In general, boaters must be aware that the laws regarding sewage discharge from vessels are likely to become even stricter with time. Some localities currently and soon many more may prohibit the discharge of all waste from a boat without any distinction between treated and untreated. An adequately sized holding tank is an important consideration. A family of four anchored out for the weekend, each using the head a half-dozen times a day can easily fill a 25-gallon holding tank, and a larger size is called for if cruising plans include being away from a marina for several days at a time. It can make sense to draw a parallel between the cruising range of a boat and the size of the holding tank which would be appropriate. Most boaters pump out at fuel docks. A high-speed, short-range boat can justify a some- what smaller tank (unless long, camped-out anchorages are a predominant cruising pattern) by virtue of the fact that the boat may be fueling up near a pump out station every couple of days or so anyway.

Many new boats are equipped with truly inadequate holding tanks as the manufacturers are concerned with meeting the letter of the law at the cheapest possible cost. On a boat any larger than a simple runabout (where portable toilets are usually found rather than any permanent sanitation plumbing), a 10-flush holding tank about the size of a breadbox may simply be one of the more visible indicators of a boat built to a budget instead of a standard. There are new boats on the market where the holding tank isn’t even properly fastened down!

Sanitation Hoses

The type and condition of the hoses which connect the head to the treatment device or the holding tank as well as the hose from the holding tank to the discharge ports on deck and at the thru-hull should be examined. The best available hose is a Heavy black hose clearly labeled for use in a sanitation system. This hose can be a little difficult to bend and costs several dollars a foot more than other available sewer hoses. Many of the other hoses in use are similar to a vacuum-system hose, but need to be made out of waste-resistant materials, as the chemicals found in human waste tend to break down many varieties of plastic and rubber fairly quickly. The cheaper hoses require replacement every few years to control both leakage and the escape of odoriferous gas. The better grade of hose doesn’t last indefinitely either, but will probably be the less expensive hose overall on a per-year-of-service basis in spite of a much higher initial cost. On a used boat, look carefully at the apparent age of the hoses as well as for signs of cracking or brittleness and for the presence of any suspicious-looking stains beneath hose connections or under the low point of any dip or loop in the hose. There should be no discernible sewage smell on a properly operating and maintained system.

High-Tech Marine Toilets

On some boats there may be a large vacuum tank incorporated into the plumbing for the head(s) as part of a vacuum-flushing system. Such systems take up some space and will add to the cost of a boat, but they offer the advantage of low-water-volume flushes which can increase the number of days a less-than-generously sized holding tank will function without requiring a trip to the Marine Plumbing – Systems and Materialspump-out station. Marine heads which flush by push-button are popular as well, and many of these macerate, or grind up, any solids as they evacuate the bowl.

Gray Water and Sumps

Gray water draining from sinks and showers will drain over-board, by gravity, where the sink or shower drain is above the waterline. Shower drains particularly are very often below the waterline, and water will drain into a small, few-gallon-capacity sump from which it will have to be dis- charged by a designated pump. A boat with a well-designed shower sump will leave little or no standing water in the sump when the pump cycle has finished. Odors from soapy shower water left to cook in a warm engine room can waft back up through the shower drain and into the formal berthing spaces.

Freshwater Supply

«Water, water everywhere but not a drop to drink…» or shower with, shave, do dishes, make soup, cook shellfish, make coffee, or wipe down the refrigerator, unless there’s adequate freshwater aboard and it’s conveniently available where and when needed.

Tank Capacity and Location

The location of the freshwater storage tank is important in the design of a boat, since at eight pounds per gallon, 150-300 gallons adds up pretty quickly. Since the weight of the tank’s contents drops as the water is consumed, it isn’t practical to simply balance a large tank by placing it opposite, say, four 8D batteries and a generator. The lower in the bilge and the more central the location of the tank, the better. Because of the need to locate a water tank low in the bilge, water will need to be pumped to any location where it is desired for use. Some boats have two water tanks directly abeam of one another and draw water from them simultaneously. The size of tank needed on a boat is determined in part by the vessel’s cruising patterns. A boat anchored out for a week with a family of five aboard would require a 300-gallon capacity to supply 8,5 gallons per person per day. A couple who cruises strictly from city marina to city marina could get by with far less.

Venting and Grounding. Freshwater tank needs to be vented so that, as the water level in the tank rises and falls, air can be inducted or displaced as necessary and no vacuum or pressurization allowed to build up in the tank. Ideally, the vent should be well above the waterline (or a loop will need to be placed in the line) to prevent possible contamination of the freshwater supply by seawater finding its way into the vent through wave action or a thoughtless nearby boater’s excessive wake. A metal water tank will also need to be connected to the vessel’s grounding system. A drain valve on a water tank is a handy feature to empty the tank for winterization or drain water which may have become contaminated and allow the tank to be cleaned.

Pressure Pumps

Water pressure is achieved by a 12-volt pump. Some systems also incorporate pressure-regulation tanks which maintain steady water pressure to open faucets without the typical fast-hammer cycling experienced on water systems without a regulator tank. Once activated by a manual switch, a pump will run as required to maintain a pre-set water pressure in the lines on the pressurized side of the pump.

Read also: Mastering the Boat Buying Process – Essential Steps from Negotiation to Ownership

Hot-Water Tank

The 12-volt pump directs water to both the cold-water faucets and to the hot-water tank. A marine hot-water tank heats water by 110-volt electrical elements when connected to shore power or a generator, or by extracting heat from the engine coolant (which is piped through a heat exchanger inside the tank). As small tanks recover heat fairly quickly, the hot-water tank on most boats does not need to be much over a 10- or 20-gallon capacity. Some larger boats with 50- to 80-gallon soaking tubs in the head will need a proportionately larger hot-water tank (as well as jumbo-capacity freshwater storage). The output side of the hot-water tank supplies all of the hot-water faucets aboard. Noting the accessibility of the hot- water tank will give a boater an idea of just how large a chore it will be when the tank inevitably requires removal and replacement.

Freshwater Makers

Boats intended for extended Cruising in Comfort on a Sailboatoffshore cruising will typically use a water purifying system to filter or distill seawater, insuring an endless supply of freshwater (as long as the system is working). A water-making system is another case where redundancy is desirable. A permanently installed system could be backed up by a hand-operated life raft-type device, or enough spare parts and technical knowledge to rebuild the system while at sea.

Dockside Hose Connections and Water Lines

Boaters who spend large amounts of time docked at marinas appreciate a freshwater inlet which allows the boat to connect (through a water hose) to the municipal water supply. Hose bib-type freshwater inlets have a pressure regulator to prevent excess water pressure dockside from bursting freshwater hoses or otherwise damaging the plumbing. Water lines throughout the vessel may be either copper or plastic and should be leak free at all connections.

Some things to look for. On a used boat, signs of present or previous leakage, such as stains under plumbing connections or warped cabinet bottoms under galley or head sinks, can alert a prospective owner to areas which, if not in need of urgent repair, may well be worth closely observing in the future. Many boats use freshwater pumps which switch on automatically as water pressure downstream from the pump drops, such as when a faucet is opened and water is drawn off. If all of the faucets are completely closed, this pump will not switch on unless there is a water leak on the pressurized side of the pump. If, during the inspection process, the freshwater pump circuit breaker is on and a water pump is heard cycling in occasional two- or three-second intervals there is either a dripping faucet or a leak from a hose or connection. Neither a plumbing leak nor a dripping faucet is acceptable on a vessel with a finite freshwater supply and will need to be corrected. While boats are designed to be used in water, it is truly amazing the amount of time that boaters spend keeping water contained where desired aboard and out of places where they would rather the water not be!