Sailing Performance Evaluation is crucial for understanding the efficiency and capabilities of a yacht. By analyzing various diagrams and performance metrics, sailors can gain insights into how their vessel performs under different conditions. Key factors such as stability, metacentric height, and engine performance are essential to ensuring a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Trials on the water offer real-time data that complements theoretical evaluations, allowing for better decision-making. Understanding these elements can significantly enhance a sailor’s ability to optimize their vessel’s performance, whether under sail or engine. Ultimately, a thorough evaluation leads to improved sailing skills and a more enjoyable time on the water.

Evaluating diagrams at home

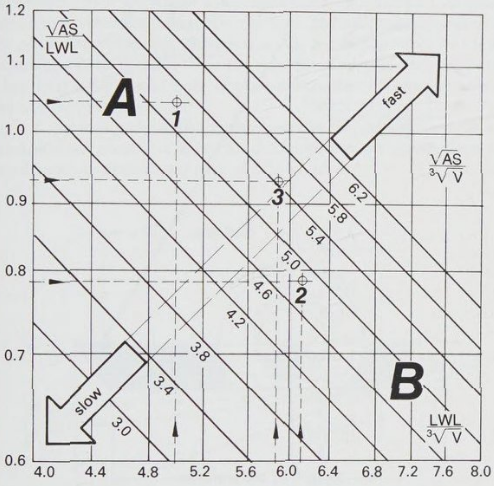

Each ratio-factor makes a statement about each individual characteristic of a boat. A diagram with the parameters waterline length, sail area and displacement puts the three most important factors for a yacht’s performance into relationship: the coefficients of Figs. Understanding Yacht Design – Key Features and Performance Ratios“The waterline in relation to the displacement displays a yacht’s weight in relation to the waterline”, Understanding Yacht Design – Key Features and Performance Ratios“The sail area in relation to the displacement produces a so-called sail-carrying number, i. e. whether a yacht carries a relatively large or small sail area” and Understanding Yacht Design – Key Features and Performance Ratios“The relationship of a boat’s sail area to waterline length indicates the dependency of a yacht’s speed on the LWL” result in the diagram for the sailing performance:

Another diagram, although quite unconventional, represents the attempt to depict a yacht’s characteristics in such a way that the viewer will see them at first glance. Everybody can draw the required sketches.

Sailing Performance Diagram

A yacht’s performance depends on several factors. Its LWL, AS and V are easily determined. Using figures from brochures you can compare the speed to be expected in comparison to that of others by using the sailing performance diagram. This is a lot more realistic than comparing boats purely by their hull speed, as it is generally as valuable as sailing the boats against each other. The theoretical comparison is based on the LWL. On downwind courses with strong winds, the LWL becomes the only speed-limiting factor apart from the rigging. High proportional values of a boat’s sail area to her waterline stand for an optimal exploitation, applied to the vertical axis of the coordinate system in Fig. 1. Another important factor for a boat’s speed is the displacement as already seen in the corresponding coefficients. The length – displacement as a measure for the distributed weight on the waterline was applied on to the horizontal axis of the coordinate system. The only thing missing is the third factor, the relation of the sail area towards the displacement. This so-called sail-carrying ability of a yacht appears again as a ladder of lines (from the bottom left to the top right).

This diagram allows you to determine the sailing performance of any yacht. The higher a boat climbs up the lines because of characteristic features, the faster it will sail in medium wind conditions. The vertical axis indicates when a yacht is fast because of a large sail area and the horizontal axis indicates whether the boat achieves high speeds as a result of light construction. Therefore, you find fast boats at the top right and slow boats to the bottom left; heavy ones on the left, under-canvased boats at the bottom. A good all-rounder will always be in the middle of the coordinate system. You can also see from the diagram whether you are dealing with a boat that is good in light winds (like boat 1 in Fig. 1) or whether the boat requires more wind (like boat 2 in Fig. 1). Boat 3 in this figure displays the best all-round qualities. You will find great similarity if you compare the theoretical values with actual sailing values. Yacht designers proceed the same way: they just do it the other way around.

For the test sails that will follow, the future buyer will in any case already know which probable qualities his trial boat has. He should not even bother to set sail in light winds if the boat reads «bottom night» in Fig. 1.

Qualities at a Glance

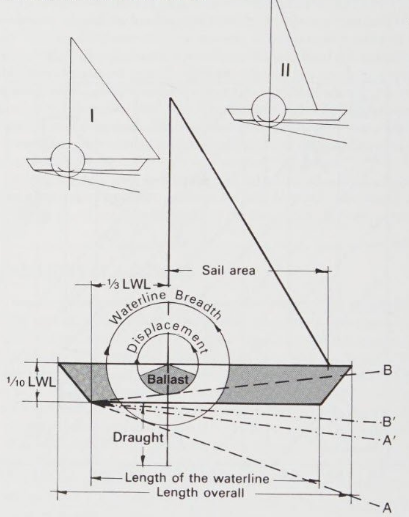

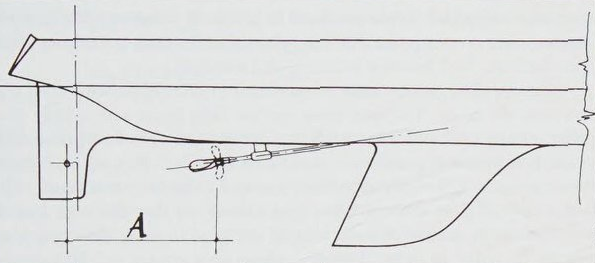

The famous yacht builder and draughtsman Robert Das developed a drawing technique (published 1966 in the magazine Yacht) that allows direction comparisons of yachts in order to detect a Understanding Yacht Design – Key Features and Performance Ratiosyacht’s characteristics at first glance. It is based on basic physical laws and has been refined through experience. You draw the boat’s hull (best scale 1:50) consisting of LOA and LWL with a free board of 0,1 LWL (as seen in Fig Understanding Yacht Design – Key Features and Performance Ratios“If you put the boat’s speed into relationship with the waterline, it results in the Froude’s value, a figure that indicates the boat’s speed”). You then draw a so-called breadth circle with half of the BWL (always use the same scale) and a displacement circle with 0,53√V. You can enter the proportion of ballast in degrees (ballast in relation to the displacement) in this circle. The luff of the sail is drawn from the front with a distance of 1/3 LWL.

Its length I is produced by 2 × 0,75√AS for the sail area; the factor 0,75 for the main sail is only there for optical reasons. The foot of the sail is entered with its simple length of 0,75√AS. The tangent A is drawn from the edge of the LWL to the breadth circle and tangent B on to the displacement circle. The Robert Das «Boat Comparison» is as simple as that!

The sail area triangle denotes whether a yacht is over- or under-canvased or whether the rig is balanced. If the leach of the symbolic sail cuts off with the waterline, her canvasing is suitable for medium wind and sea conditions. The two smaller diagrams show an over-canvased boat (I) and an under-canvased boat (II).

The line A (tangent to the breadth circle) gives a rough impression of the waves. The size of the angle with which it runs aft is determined by the boat’s beam. Therefore, line A permits rough estimations with regard to the yacht’s speed (shallow tangent). It also denotes whether it is narrow or wide, because the more acute the angle, the slimmer the boat.

Line B as a tangent on the displacement circle displays the relationship of the boat’s waterline length to its displacement. It is therefore an indication as to whether the boat is heavy or light, and subsequently determines the possibility of planing. According to Fig. 2, speeds above 2,43√LWL are not possible if line B is below the waterline. Experience has shown that a keel boat is only faster if the displacement in tons is five times or more the waterline in metres.

Of course, a yacht drawn in this symbolic way does not constitute a constructional plan. It is purely for the purpose of comparing boats and simultaneously displaying them optically.

Performance Details: Trials on the Water

If you want to get to know a yacht properly you have to sail it. Everything that has been said so far serves simply to assist the evaluation of a yacht without actually experiencing the performance under way. To sail the yacht eventually is the icing on the cake. With your acquired theoretical knowledge, you will evaluate the boat with your eyes open because you can predetermine some of the characteristics and will therefore experience them more intensively in practice. Whether you change your mind about characteristics that you theoretically determined as negative when you actually sail the yacht is another thing. The important thing is to combine theory and practice.

Under Sail

To understand a yacht’s characteristics such as good speed, height to wind- ward, manoeuvrability and so on, is something that requires experience and time. Seldom can you lay your hands on ‘trial boats’ for a long enough period, be it at boat shows, in their element, or in boatyards. Nine times out of ten there are other customers aboard with you, so that the trial sail is handled by somebody from the boatyard or yacht broker who is familiar with the boat. You therefore need to plan some standard manoeuvres that will reveal the yacht’s character even over a limited period of time.

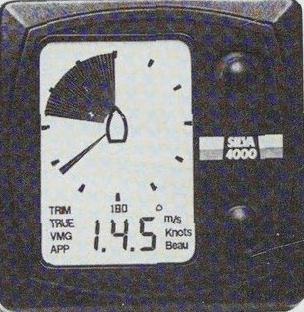

Speed. If you want to establish a boat’s potential speed, in practice you will need a compass and a speedometer. Nowadays, these instruments are standard equipment. Sometimes, the wind makes it more difficult: with a sufficient amount of sail it has to blow strongly enough for a boat to reach hull speed on an off-wind course. You can recognize this on the waves behind the stern; the wake runs smoothly without turbulence from the lower transom. This is when the boat sails at 2,43√LWL knots.

If you compare this speed with that of the speedometer, it produces a correction factor of I if true speed and speed of the speedometer are equal. For different speeds, the correction factor is produced from the quotient Vtrue/Vspeedometer, i. e. from the true speed divided by the speed measured. The speed indicator is therefore not gauged (differences might be slightly variable for other courses and speeds), but it is sufficient for the test. Now you sail three courses: close to the wind, 90 degrees off the wind, and downwind, whereby you need to notice whether an increase in speed is due to a gust or whether the helmsman has fallen off his course. Those three average speeds already display a yacht’s potential speed. If you follow the same procedure in lighter winds or in the same wind force but reefed, you will find out about the boat’s qualities in fair weather.

If you are lucky and the wind increases, you can also check out the qualities in heavy going; a good all-round boat should be able to carry her «windward canvas» with ease up to a force 4.

You can also draw a so-called apple diagram with the speeds of the three courses. More courses would obviously be better. If you assume that the speed of an average boat differentiates by 1 knot between sailing close-hauled (45 degrees) and on a beam reach (90 degrees) and by a maximum of 2 knots between a downwind leg (180 degrees) and a broad reach (135 degrees), you will have two extra points for this polar diagram.

Height to windward. You can easily determine your height to windward by using the compass when tacking: you measure the tacking angle of about five tacks. Divided by two, it will give you your height to windward. It generally lies between 38 and 45 degrees, whereby the smaller angle is for slim boats with a good keel profile (also for a pointed long-keeler), and the higher degrees are for broad motorsailers. All other boat types are somewhere in between.

The optimum height to windward, i. e. the angle to the true wind, which lies between extreme pinching and acceptable forward drive, can be obtained from the polar diagram: it displays visibly how much the boat speed reduces with increasing height to windward. The optimum angle of height is obtained by applying a horizontal tangent to the boat’s speed curve (polar diagram).

Ultimate speed to windward. Measuring the speed of a yacht to windward does not depend on the maximum speed, what is important is ultimate speed made good to wind-ward (as you can read from the polar diagram after applying the tangent). On board a yacht you can obtain the final speed, Vwindward by reading boat’s speed through the water, Vspeed, and simultaneously determine the course angle towards the true wind. By definition, it is the product from speed and cosine of the course angle.

The same applies to the ultimate speed downwind: it also pays to tack in front of the wind (to prevent sailing by the lee). A lot of sailing instruments already calculate speed and course angle on board, so that you might be able to read the final speed of your trial boat. A good performance to windward will be shown by a yacht with a high speed made good to wind- ward at a given speed of the true wind VW. The larger the ratio Vwindward/Vwind the greater are (for example) the chances of success on a triangular course and the more effective – regarding the lateral force – is the keel and rudder, not to mention the sails!

Turning circle. A good option for displaying a Choosing the Right Yacht – Essential Considerations for Every Sailorboat’s manoeuvrability is to turn a circle: from a windward course with maximum speed you put the rudder across without handling the sails and then check the time. Light boats with narrow fin keels and free-hung spade rudders require between 20 and 30 seconds, a fin-keeler with skeg in front of the rudder requires between 30 and 40 seconds, and heavy boats with long keels require between 40 and 60 seconds.

A design problem that occurs over and over again when turning a circle is to find a boat that is highly manoeuvrable and at the same time highly stable. All compromises are somewhere in between. Another factor that appears when turning a circle is the effect of the rudder: if the vertical rotating axis of the hull (usually shortly behind the front edge of the keel) and the rudder’s point of effort are too close together, the boat reacts sluggishly.

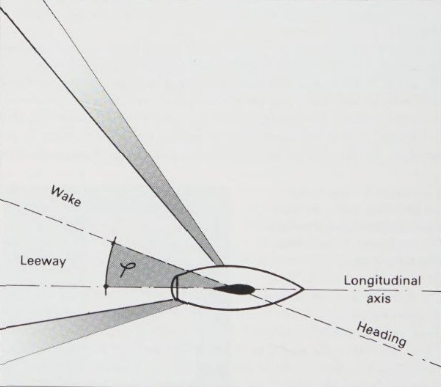

Leeway. A good indication of the effectiveness of the keel and the rudder against the lateral force of the water is the boat’s leeway. The less leeway a boat has the better. For an exact determination of a boat’s speed and true course with induced and true wind, the leeway is as important as the speed made good to windward. Measuring the leeway is quite difficult. You would need to measure in front and far behind the boat in undisturbed water.

At the moment, you have the option of determining the leeway by estimating (or taking a bearing) the angle of the boat’s stern wake to her longitudinal axis. A small angle signifies sufficient lateral area with good height to windward. With large angles you have to be careful when mooring the boat as it tends to drift sideways.

Heeling. In past years it was quite normal for yachts to heel up to the gunwales – even in relatively light winds. Boats with large overhangs (Skerry cruisers or Dragons) are designed to sail heeled, as it elongates the waterline. Modern, wide fin-keelers follow the contrary concept; their lines are perfect if the boat can be sailed upright. Their speed can only be maintained by reefing early. Too much heeling makes the boat unbalanced and difficult to manoeuvre because the rudder comes out of the water too easily.

If you want to avoid spending all your time sitting on the windward side of the boat as a cruising sailor, the boat will need sufficient stiffness. You can immediately recognize the stiffness of a boat if you step on to the side of a 10 metre yacht. Whether a yacht ts tender or stiff is irrelevant to stability as the ballast only becomes effective with increased heeling. Modern cruisers have to put a reef in when the boat is heeled only at about 30 degrees, while slimmer long cut-away keelers can continue to sail up to a heeling angle of about 50 degrees.

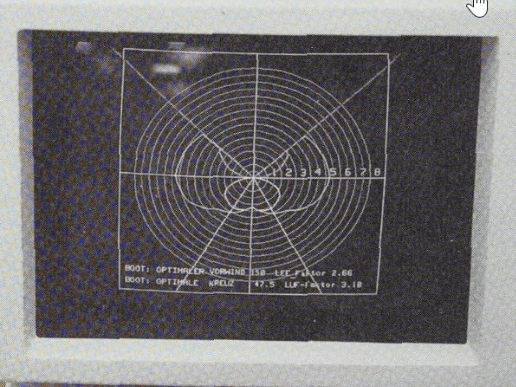

Sailing performance by comparative values. Why can’t a computer come up with a quick estimation of a yacht’s sailing performance? In fact, there is a computer that does just this. Microelectronics have presented a large selection of measuring devices for yacht navigation, but no matter how good they are, once on board these wind- and water-measuring devices are subject to a series of errors. For example, a variable stream flow on different courses, the boat’s yawing and rolling movements at the log, heeling and upwards movement of the air flow due to the sail at the wind indicator are just a few such errors.

Dr Eng H Brandt, Professor of Hydrodynamics at the Technical University in Berlin, has developed a calculation method that allows comparisons to be made between similar boats, and that produces a yacht’s sailing performance by means of a performance-ratio. For this you need details of the:

- boat’s LWL;

- BWL;

- sail area and displacement,

as are also required in the sailing performance diagram (Fig. 1). You also enter two additional correction factors in the computer: these are resistance and sail quality. The program calculates sailing performance, together with the measured values of the log and wind indicator, that is not limited to the determination of the currently sailed speed to windward. It also includes the theoretical boat speed of a comparative boat with identical initial data for boat speed, wind angle and leeway.

As an added feature, you will get additional values for the resistance and forward drive, whose data have been collected in a series of lengthy measuring tests. The computer program considers the aerodynamic force of the sails, the sail-carrying ability, i. e. the yachts stability, and the complete range of resistances such as towing and wind resistance, leeway and heeling. The aim of a sailing performance calculation is that the forward drive corresponds to the yacht’s hydrodynamic resistance and therefore produces a theoretical boat speed. This computer is built by the German instrument manufacturer VDO, but can it replace personal evaluation and intuition?

Under Engine

As harbours and marinas become more crowded, it is important to manoeuvre under engine, because in most cases you will not be able to come alongside or cast off under sail. You have to use your engine in order to park the boat in a narrow mooring slot. It also helps to be able to over-come a lull and stem a tide.

Whether a sailing yacht benefits from an engine depends as much on performance and the propeller fitted as on the optimal thrust on the rudder. Changes can easily be made if the diameter of the prop is not geared to the engine’s performance and its rotating speed is not suited to the boat’s speed. It becomes more difficult if the prop is situated too far away from the rudder. You need to do major refit if the rudder blade is to be brought into the prop’s thrust.

Speed. Your engine should have two speeds, top speed and cruising speed. Auxiliary propulsion’s first priority should be to achieve the boat’s hull speed, the second should be that it works quietly, economically and without vibration. It is suggested that yachts that sail in open seas have a 10-20 percent performance reserve. Often, the hull speed is not reached, which is largely the result of an incorrect angle of the folding prop rather than the engine’s performance. However, a folding prop has less resistance when sailing in comparison to a fixed prop. Tests in the experimental tank have shown that speed loss is only 0,01 knots at a speed of 5 knots for folding props, while a fixed prop reaches values of 0,8 knots.

The cruising speed is generally defined as 80 percent of the top speed. The boat is sailed on the rev-counter and either measured with a verified log or by sailing a measured mile: course and reciprocal course divided by two in order to eliminate winds and current, Remember, one knot is one sea mile per hour.

Turning circle and reverse drive. A good way to establish a yacht’s manoeuvrability under engine is to turn a circle. You drive the boat to starboard and port at cruising speed and check the time it requires to complete the circle. If you turn the boat to port, it generally requires less time because most boats have right-handed props that reinforce the water flow to the rudder. Turning times between 10 and 30 seconds are acceptable for a yacht. The higher value is more for the cut-away keeler.

The diameter of the circle should not exceed 1 1/2-2 boat lengths. Everything above this requires an inspection of the rudder and propeller. If, for example, a wave comes out straight behind the fin, the rudder of the fin-keeler often does not get enough thrust from the propeller because it is situated too far away, while the propeller may possibly prevent a good stream thrust in a long-keeler. Boats like this can only be manoeuvred with a lot of speed in crowded harbours. An indication of good manoeuvrability is always if the boat’s rudder handles well when reversing. Front-balanced free-hanging rudders are very effective in this case, although dangerous: if the push backward is too large, it easily rips the tiller from the helmsman as it directly oversteers. A rudder with a skeg ts friendlier to handle, although not as effective as the spade rudder. A yacht has good manoeuvrability if it can be reversed into the mooring slot. If the rudder-to-propeller alignment is correct, it will be easier to reverse the boat because boats steer with their sterns.

Stopway. Though a yacht has no brake as such, it should at least be able to stop in reasonable time. The loss of way – or stopway – indicates the period of time that is required before you have to reverse in order to cease to make headway at a certain point. For this, you drive the boat at cruising speed and check the time between reversing and standstill.

The complete process must be measured in calm water with wind and waves on the beam, The time measured for light boats with a large propeller is between 8 and 12 seconds, for heavy boats or boats with folding props, it is up to 20 seconds or more. The formula:

produces the stopway;

- v – is the boat speed in knots;

- t – the time in seconds.

The factor of 0,26 is to convert knots into metres, so that the total loss of way is given in metres. A yacht should not require more than two boat lengths in order to stop. Anything above this results in difficulty in manoeuvring.

Stability and Metacentric Height

First-time buyers in particular are always anxious as to whether the boat is self-righting. With Keel Types Comparison and Additional Design Considerations for Sailboatskeel boats, the answer is generally «Yes». However, the location and amount of ballast carried will affect the stability, and also the behaviour in a seaway: too much righting moment will produce a jerky motion as the hull first heels, then abruptly comes upright. A comfortable cruiser should have only sufficient ballast to ensure that inversion is all but impossible, but not so much as to impart a violent motion in a seaway. Two relatively simple tests display a given boat’s stability in relation to other well-known designs.

Boat builders use the word stable for the balanced condition of the complete boat. A yacht’s safety is the heeling stability that allows it to return upright from extreme angles. A measure of stability is defined as the metacentric height GM, the distance between the metacentre and centre of gravity (see Choosing the Right Yacht – Essential Considerations for Every Sailor«Stability»). It takes considerable effort to calculate the stability, and brochures do not offer all the required details.

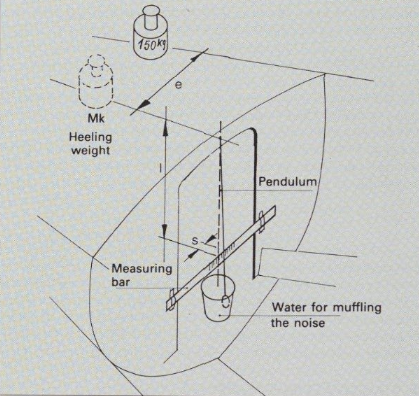

There are two methods for the practical interpretation of GM, both of which are easy to perform even on a yacht that is already afloat. In method l the yacht is heeled on a calm day with all equipment, i. e. gear, crew and half-filled tanks. The boat is tied loosely to the mooring and a weight is placed on to the side deck and shifted from the middle towards the side (you can use the crew!), so that the boat heels visibly. The measuring device for the heeling angle is a pendulum that is installed below deck (string with a small weight). The metacentric height in metres is obtained by using the heeling weight m (about 150 kg for a 10 metre yacht), the length of the shifting way on deck e, the swing of the pendulum s, the length of the pendulum l and the displacement of the yacht V:

The other method is even more simple: you measure the yacht’s rolling time. For this, you heel the boat and measure the time that the top of the mast requires to complete a swing from one side to the other. If several swings are measured, the result becomes more accurate. When the GM is calculated, the result has to be divided by the number of swings. The formula is:

- Bmax – is the largest breadth in metres;

- T – the swinging time in seconds (one swing represents the natural swing ofthe yacht);

- С – a factor for differentiating between heavy and light yachts (1,56 for heavy and 1,24 for light; other boats are somewhere in between).

Depending on the yacht’s stability, you measure between 4 and 16 seconds for her natural swing. Both formulas are approximate and are valid for the initial stability, i. e. for heeling angles up to about 15 degrees.

Stability Comparison

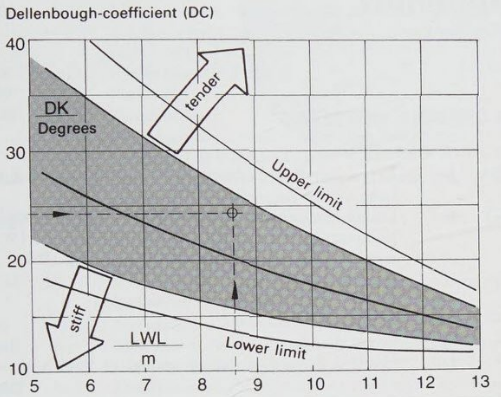

A yacht’s metacentric height on its own does not reveal anything. The lever curve is missing, and this, in most cases, is not obtainable. You can help yourself by comparing the stability of other yachts. Designers use an empirically established value, the Dellenbough-coefficient, because even for them the calculation of the displacement’s centre of effort and the waterline’s momentum of inertia for each heeling angle is quite long- winded. The Dellenbough-coefficient (DC) indicates a yacht’s heeling angle close-hauled in a force 4 with the wind diagonal to the heading(equivalent to a wind pressure on the sail of 4,88 daN/m2). The value is only useful if you are able to make comparisons. These are available withthe aid of a diagram (Fig. 8). It shows the DC-values applied above thewaterline, which have been established from IOR rating certificates of the German Sailing Association (DCV). The calculated coefficient and the waterline offer a good impression of a yachts stability. The Dellenbough- coefficient is calculated as follows:

The wind pressure ρ is thereby equivalent to 4,88 daN/m2, the sail area AS in square metres, the sail’s centre of effort H above the WL in metres, the draught T in metres, the metacentric height GM in metres, and the displacement V in kilograms. The result is the DC in degrees.

The Dellenbough-coefficient is the practical counterpart of the sail- carrying number made up from the sail area and displacement, which also indicates the comparative value as to whether a yacht is tender or stiff.

Additionally, it gives rough details about the Recommendations for Choosing the Type of Boattype of boat. The metacentric height of an upright position is used. It does not consider the additional influence of the shape.

| Beaufort Wind Scale | ||

|---|---|---|

| General description | Wind speed (knots) | Sea state |

| Calm | Less than 1 | Sea like a mirror |

| Light air | 1-3 | Ripples: no foam crests in open sea |

| Light breeze | 4-6 | Small wavelets with crests that do not break |

| Gentle breeze | 7-10 | Large wavelets; crests begin to break: some white horses |

| Moderate breeze | 11-16 | Longer waves with white horse |

| Fresh breeze | 17-21 | Moderate waves; many white horses; some spray |

| Strong breeze | 22-27 | Large waves with white foam crests; spray |

| Near gale | 28-33 | Sea heaps up; white foam blown in streaks |

| Gale | 34-40 | Moderately high waves; some spindrift: visible foam streaks |

| Strong gale | 41-47 | High waves; crests begin to topple and tumble; dense foam streaks; spray affects visibility |

| Storm | 48-55 | Very high waves with crests: sea surface becomes almost white; visibility badly affected |

| Violent storm | 56-63 | Exceptionally high waves; sea covered in foam; visibility badly affected |

| Hurricane | 64+ | Air filled with foam and spray; sea white; visibility seriously affected |

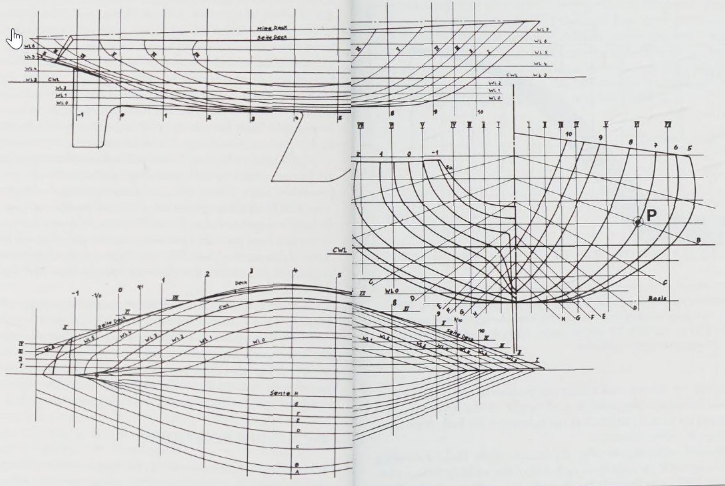

Reading Lines Plans

Though there are still individually built yachts, most these days are factory- produced. Their hulls are made from a mould, which is used for all subsequent hulls. A lines plan is only required for production of the mould. In spite of this, the resultant cast shows the lines that characterize the yacht’s hull. At boat shows, if one looked at hulls whose shapes would be eligible for industrial design awards, it would be those with the most eye- catching lines plans. A lines plan’s detailed information regarding a boat’s hull is much better than looking at a photo. Very often you get more information about a yacht’s character by looking at the lines plan than if you saw the vessel standing on land. Even if you walk around the boat, you will not see all the qualities as well as if you studied a plan.

Read also: Maintaining and Modifying Your Sailboat

With a little bit of practice, you will soon develop a feeling for the beautiful lines of a yacht. Except for IOR hulls, all lines run smoothly without bumps and dents. Boat builders in Germany call this «A line of strakes». This derives from the low German and means «stroking». If you watch how a wooden hull is cleaned and polished you soon understand the meaning: the boat builder runs his hand over the hull in order to recognize uneven lines that do not «strake» – or, to put it another way, are not fair.

The lines should strake so that the water flow glides along the yacht when sailing and does not produce resistance through turbulence. This leads to the conclusion that a good straking yacht is also a fast yacht, and because more yachts today are built to sail fast by lessening displacement, a heavy yacht with a smooth underwater line is at least not slow. You will understand this if you look at the lines plans of older boats (very rarely will you be able to see plans of newer factory-built boats). A trained eye will soon be able to differentiate and this will make the choice of the right boat simpler.

A yachts lines are curved, not straight, and both halves of the hull must be exactly symmetrical and have equally straking lines if the performance is to be acceptable. This requires an accurate drawing plan whose measurements are later scaled up. In times when such design was not computer-aided, at least the strake was correct because the points on the drawing were connected by using a strake batten, which only permits fair lines and curves. A plotter, in comparison, does not realise if a curve is too sharp or whether a line has a bump. Sometimes, in any case, bumps and dents are actually required, so that the boats conform to the IOR ratings.

The lines plan displays hulls from three different angles: longitudinal elevation, horizontal section and profile. In the longitudinal and horizontal section the bow is always on the right and the after part always to the left; the horizontal section and the profile generally display only one half of the boat, while the other half is the mirror image. In order to obtain a complete drawing plan, the hull is cut open several times in different directions. The borderlines of these cuts are curves that are known as sections waterlines, cuts and centrelines.

Sections created when the hull is cut into equal slices (cross-sections) from the stern to the bow. The largest section is the midship section. Because it is so important, both port and starboard sides are displayed. On the right of the centreline are the sections of the forepart, on the left those of the stern. The profile section of the drawing plan is the section. Here, the sections are shown as straight lines. The lines are numbered consecutively from aft from 0 onwards.

Waterlines are shown when the hull is cut into horizontal slices. The borderlines are the waterlines. The upper part of the horizontal plan represents the waterline section. The most important waterline is the construction waterline CWL. It is the calculated waterline on which the boat should float. Because the underwater hull is mostly responsible for a yacht’s performance, the waterlines are taken at closer intervals.

Cuts are for checking the section and waterlines; longitudinal sections are placed parallel to the midship area and these divide the hull into perpendicular slices. These curves are found again in the longitudinal plan.

Centrelines are cuts taken from the midship area, so that as many sections as possible are cut vertically. They are drawn into the section plan as straight lines and their border-curves are placed in the horizontal plan below the waterline plan. The centrelines are vital when actually building the hull. If they are fair, the seams are all right. Errors can be localised with the centrelines.

Section and waterline plans are of special importance when evaluating a yacht. They provide information about the yacht’s cross-section and there fore about stability, draught and breadth. They also offer information about the boat’s displacement and form resistance, which is important for the speed. The waterline plan offers details about the fullness of the boat’s underwater hull and about the shape and size of keel and rudder, etc. It also gives you an idea about the water flow around the hull.

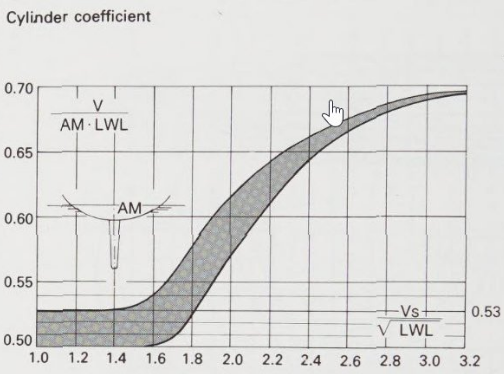

Cylinder Coefficient

At boat shows, dealers sometimes use the boat’s low cylinder coefficient as a selling point. When dealing with cars, one nowadays talks about the low CW-value, which the buyer cannot easily prove. It is similar to the hydrodynamic shape of a boat. A hydrodynamically favourable shape has always been obligatory for a yacht, although nobody knows the exact definition: today we try to give it a definition that comes pretty close to the cylinder coefficient.

The following is a brief explanation so that you know what it is a about. Because shallow wave systems use less energy than steep ones at equal length, the fullness of the hull’s ends (bow and stern) in relation to the midship section plays a vital role in the evaluation of a sailing yacht. The fullness influences the position and height of the waves and the dynamic buoyancy that is produced at the bottom of the hull. Both combined produce the wave resistance.

The cylinder coefficient describes the fullness of the hull, by dividing the overall resistance V through the length AM of the midship section multiplied by the LWL. The formula for the cylinder coefficient is therefore: V/AM × LWL. If it is applied to the speed-to-length ratio, the optimal values first produce a shallow curve and then a steep rising curve, as a criterion for the wave-producing resistance. The cylinder coefficient is between the value of 0,50 and 0,70, depending on the relative speed (VS/√LWL) the boat was designed for. Heavy displacement yachts have narrow ends, which correspond to a low coefficient, while modern light displacement yachts, which achieve higher speeds on a broad reach or on a run, have fuller ends and therefore a higher coefficient. Pure fair-weather yachts that sail with slow speeds have a value of between 0,50 and 0,53. Cruisers with values between 0,53 and 0,55 have good all-round qualities. Each speed had its corresponding cylinder coefficient: high values (up to 0,7) if the ends have a large displacement, as do light displacements with wide aft sections for planing. Unfortunately, the cylinder coefficient is not easily established, at least not at boat shows, but if some dealers use it for advertising they should at least state it in their brochure.