LNG Market Dynamics play a crucial role in shaping global energy trends. As demand for liquefied natural gas rises, understanding price fluctuations across regions like the US, Europe, and Asia-Pacific becomes essential. Current developments, including shifts in crude oil prices and evolving agreements, further influence this market.

- Introduction

- LNG Reference Market Price

- The US market

- The European market

- The Asia-Pacific market

- Current developments

- Price Indexation

- Crude Oil Prices

- Oil Indexed Price Formula

- Spot and Short-Term Markets

- Netback Pricing

- Price Review or Price Re-opener

- Recent Pricing Issues

- LNG and Gas Contracts

- Introduction

- PSC v. Licenses

- Preliminary Agreements

- Domestic Gas Sales Agreement

- LNG Sale and Purchase Agreement

- Transportation and Discharge

- Volume

- Level of Commitment

- Cargo Diversions

- Price

- Technical

- Miscellaneous

- Miscellaneous Agreements

- Project Enabling Agreement

- Shareholders Agreement(s)

- Liquefaction Agreement

- Gas Feedstock Agreement

- EPC Contracts

- Financing Agreements

- Transportation Contracts

- Facilities Sharing Agreements (FSA)

- Terminal Use Agreement

Additionally, price indexation and short-term market strategies are key factors that affect pricing. Stakeholders must navigate a complex web of contracts and commitments to optimize their positions in this competitive.

Introduction

As opposed to crude oil, LNG does not feature a harmonized global price. In contracts, the price of LNG is segmented into regional markets, the main ones being:

- the Asian market (Japan, Korea, and China) with the Japan Customs-cleared Crude price index;

- the European market with the National Balancing Point price index;

- the North American market with the Henry Hub price index.

LNG pricing has historically been tied to crude oil, as the replacement fuel to natural gas. Pricing into Japan and much of Asia was based on a percentage of the price of Japan Customs-cleared Crude (JCC), which is the average price of custom-cleared crude oil imports into Japan as reported in customs statistics; nicknamed the Japanese Crude Cocktail. As an example, a pricing formula may be «LNG price = JCC × 0,135» where JCC is further defined as the previous three monthly averages of JCC priced in yen and converted into US dollars. In Europe, Brent has been favored in oil-linked LNG pricing formulas.

LNG pricing in parts of Europe and in North America have relatively recently been tied to readily available natural gas indices. In Europe, a main index is NBP or National Balancing Point, a virtual trading location for the sale and purchase and exchange of UK natural gas. In North America, a main index is Henry Hub, a distribution hub in South Louisiana which lends its name to the pricing point for traded natural gas futures contracts.

LNG Reference Market Price

As noted in the previous section, LNG pricing is following the global trend that has been underway for many decades, whereby instead of being priced relative to oil, it is starting to be priced based on a variety of established and emerging global reference prices. This is generally referred to as «gas-on-gas» pricing as it is a measure of the relative supply and demand in LNG Market Trends in Global Gas Dynamicsnatural gas markets, quite independently of whether the oil market is in balance or not. From an economist’s point of view, this would be the established way to set the appropriate market clearing price for a globally traded commodity.

The US market

The historical rationale for gas reference pricing emerged from the development of a liquids wholesale market in the US, with exchange-traded futures contracts to support a pricing mechanism that was not vulnerable to undue influence from a single buyer or seller, and was derived from a transparent, market-based mechanism. Historically, natural gas prices were fixed by the government, but in 1992, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued its Order 636. Prices were decontrolled and interstate natural gas pipeline companies were required to split-off any non- regulated merchant (sales) functions from their regulated transportation functions. This unbundling of gas contract pricing and transportation contract pricing meant that exchange-traded gas contracts, based on Henry Hub and other secondary hubs, were established, and the industry moved to market-based indices for pricing purposes.

The European market

In Europe, this same trend was first established in the UK, following gas market deregulation in the mid-1990s, and the emergence of National Balancing Point (NBP) pricing, which, though similar to Henry Hub, is not a physical place. In Continental Europe, the so-called Title Transfer Facility (TTF) has now become an equally dependable mechanism for long-term pricing, though Southern Europe is still transitioning to a mechanism of Analyzing the Dynamics of LNG Pricing: Regional Markets, Indexation, and Recent Challengesgas-on-gas pricing, as new hubs start to emerge.

The Asia-Pacific market

The first signs that a new pricing basis was emerging for the Asia-Pacific region occurred in the early 2010s with the signing of Henry Hub-based LNG tolling contracts. At the time, buying gas in the US and paying a tolling fee to put it through one of the emerging LNG liquefaction facilities, represented a lower landed price in Japan and other SE Asian countries, compared to traditionally oil-priced gas.

A number of attempts are being made to establish a pricing index for the Asia-Pacific market, including the so-called JKM index (Japan-Korea-Marker) and also the Singapore Gas Exchange (SGX) spot price index known as SLiNG, which is intended to represent an exchange-traded futures market for LNG based on gas being traded at or around the Singapore LNG facilities. At the time of writing, no index exists that is considered sufficiently dependable for use on long-term contract pricing.

Current developments

The LNG sector has been relatively slow to move away from oil-based pricing. There are many reasons for this, but the main brake on pricing change for LNG has been the lack of availability of a reliable, transparent pricing reference for gas, similar to Henry Hub or NBP, in the Asia-Pacific region, which accounts for about two-thirds of LNG consumption.

The other feature of LNG, compared to pipeline gas, is that it is bought and sold in single ship-borne cargoes, instead of being commingled within a pipeline system, and this too has tended to slow down the development of gas on gas mechanisms.

In Europe, over the last decade, the majority of traded gas has now migrated from oil-based to gas on gas based pricing, and some commentators believe that gas-on-gas based pricing will gradually replace oil-based index pricing, particularly as new LNG projects bring additional LNG into the global markets.

An increasing number of African countries are considering moving to LNG imports, or establishing relatively smaller scale projects. Because these are under development and/or negotiations, no pricing has been established as yet.

Price Indexation

Natural gas may be sold indexed to the price of certain alternative fuels such as crude oil, coal and fuel oil. The natural gas feedstock prices into the LNG plants are sometimes indexed on the full revenue stream of the LNG plant including LPG and propane plus (other gas liquids), as in the case of the 2009 amendment of the NLNG contract in Nigeria. Such a pricing mechanism is markedly different from the one found in traded gas markets, where price is determined solely by gas demand and supply at market areas or «hubs».

In the United Kingdom, around 60 % of the gas is sold at the National Balancing Point (NBP) price and the rest at an oil index price based on old long-term contracts. The oil-indexed and hub-priced contracts co-exist.

On the European continent, the case is different. Oil-indexed contracts dominate, with hardly any hub-priced long-term contracts. The continental markets are mainly supplied on a long-term take-or-pay basis. However, a number of short-to-medium contracts do exist which are either fully or partially hub-priced.

Crude Oil Prices

Different crude oil prices are used for the oil index in LNG long-term contracts such as:

Japanese Custom Cleared crude (JCC). JCC is the average price of crude oil imported into Japan and published by the Japanese Ministry of Finance each month. It is often referred to as the Japanese Crude Cocktail. The JCC has been adopted as the oil price index in LNG long-term contracts with Japan, Korea and Taiwan. LNG pricing for China and India is also linked to crude oil prices but at a discount to Korea and Japan. The discount reflects the fact that China and India, although short of natural gas supplies have other sources of natural gas that LNG complements. As a result, China and India have some additional market leverage in negotiating contracting terms.

Average price of Indonesian crude oil (ICP). PERTAMINA uses the average price of Indonesian crude oil (ICP) for the supply of LNG from the Bontang and Arun plants.

Dated Brent Crude. Dated Brent is a benchmark assessment of the price of physical, light North Sea crude oil. The term «Dated Brent» refers to physical cargoes of crude oil in the North Sea that have been assigned specific delivery dates, according to Platts. Kuwait, Pakistan, and many European LNG prices are indexed on Brent.

Coal indexation. In markets where gas is used to fuel power generation, some LNG buyers have pushed for LNG indexing against substitute fuels such as coal. Coal indexation has been used for many years in a Norwegian gas sales contract to the Netherlands and is also an indexation parameter in the Nigeria NLNG contract to Italy. This parameter may become more common if clean coal technologies are used to satisfy incremental baseload electricity demand, or if electricity generators come under increased pressure to reduce carbon emissions under the Kyoto protocol.

Oil Indexed Price Formula

Approximately 70 % of world LNG trade is priced using a competing fuels index, generally based on crude oil or fuel oil, and referred to as «oil price indexation» or «oil-linked pricing». The original rationale for oil-linked pricing was that the price of gas should be set at the level of the price of the best alternative to gas. Historically, the best alternative was heavy fuel oil, crude oil or gas oil. This was especially the case in the Asia-Pacific region, which historically has represented the largest buyers of LNG, including Japan, Korea and Taiwan.

In the Asia-Pacific region, LNG contracts are typically based on the historical linkage to the Japanese Customs-cleared Price for Crude Oil (JCC, or the «Japanese Crude Cocktail»). This is due to the fact that at the time that LNG trade began, Japanese power generation was heavily dependent on oil so early LNG contracts were linked to JCC in order to negate the risk of price competition with oil. The formula used in most of the Asia LNG contracts that were developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s can be expressed by:

Where:

- PLNG = price of LNG in US$/mmBtu (US$/GJ × 1,055);

- α = crude linkage slope;

- Pcrude = price of crude oil in US$/barrel;

- β = constant in US $mmBtu (US$GJ × 1,055).

Historically, there was little negotiation between parties over the slope of the LNG contracts, with most disagreements centered on the value of the constant β. Following the oil price declines of the 1980s, most new LNG contracts incorporated a floor and ceiling price that determined the range over which the contract formula could be applied. Since suppliers had to make substantial investments in LNG liquefaction trains, a pricing model developed that provided a floor price. For suppliers, this floor limits the fall in the LNG price to a certain level, even if the oil price were to continue falling. Conversely, buyers are protected by a price cap, which restricts LNG price rises when oil prices rise above a certain point.

More recently, the historic price linkages to oil have been called into question as more LNG supply comes on the market from new LNG exporters, such as the United States, which developed a pricing mechanism linked to US Henry Hub. At the same time, the traditional LNG buyers, such as Japan, have balked at new contracts linked to oil, claiming they no longer make sense. As the LNG market continues to evolve, there are likely to be more and more creative solutions to pricing LNG.

Spot and Short-Term Markets

In recent years, the LNG markets have seen the emergence of a growing spot and short-term LNG market, which generally includes spot contracts and contracts of less than four years. Short-term and spot trade allows divertible or uncommitted LNG to go to the highest value market in response to changing market conditions. The short-term and spot market began to emerge in the late 1990s-early 2000s. The LNG spot and short-term market grew from virtually zero before 1990, to 1 % in 1992, to 8 % in 2002. In 2006, nine countries were active spot LNG exporters and 13 countries were spot LNG importers.

Due to divergent prices between the markets in recent years, the short-term LNG market has grown rapidly. By 2010, the short-term and spot trade had jumped to account for 18,9 % of the world LNG trade. In 2011, the spot and short-term again recorded strong growth, reaching 61,2 MTPA (994 cargoes) and more than 25 % of the total LNG trade. Asia attracted almost 70 % of the global spot and short-term volumes primarily due to Japan’s increased LNG need following the March 2011 Fukushima disaster, which took Japan’s nuclear reactors offline. This lost power was replaced with LNG. Spot and short-term LNG imports into Korea almost doubled (10,7 MTPA) and almost tripled for China and India with both countries importing a combined 6,5 MTPA of LNG.

By the end of 2011, twenty-one countries were active spot LNG exporters and 25 countries were spot LNG importers. The growing number of countries looking to participate in the spot market is indicative of the increased desire for flexibility to cope with market changes, unforeseen events such as Fukushima, as well as the increased number of countries now participating in the LNG markets.

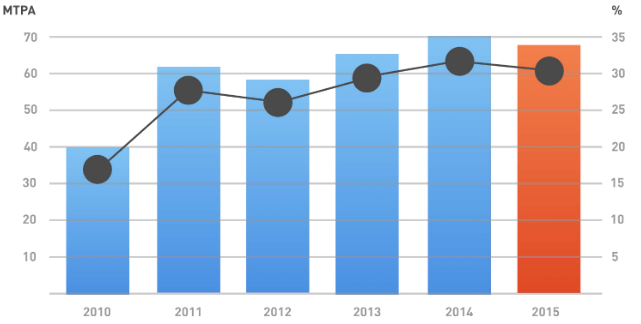

In 2015, global LNG trade accounted for 245,2 MTPA, a 2,5 % increase vs. 2014. There are now 34 countries importing LNG and 19 countries that export LNG. Approximately 28 % of global LNG volumes (68,4 MTPA) were traded on a spot or short-term basis.

The following chart shows the growing importance of spot and short-term sales in global LNG trade.

Netback Pricing

The concept of «netback» pricing is particularly important for producing countries because netbacks allow the countries to understand the varying value of LNG in different destination markets. Netbacks are calculated taking the net revenues from downstream sales of LNG/natural gas in the destination market, less all costs associated with bringing the commodity to market, including pipeline transportation at the:

- destination;

- regasification;

- marine transport and,

- possibly liquefaction;

- and production;

- depending on the starting point of the netback.

Netbacks allow the producer and producing country to assess the relative attractiveness of different destination markets for exported LNG.

There is no single formula for determining the netback price as it depends on specifics of the deal and is determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the start and delivery point of the LNG sales contract and the particular destination market involved. The starting point for calculating a netback price can be at the well, at the inlet to a liquefaction plant, or at the exit of the liquefaction plant. The delivery point of the LNG sales contract can be at the liquefaction facility (a free on board (FOB) sale, or a costs, insurance and freight (CIF sale)), or at the destination market (a delivered at terminal (DAT) sale, or a delivered at place (DAP) sale). The terms DAT and DAP have replaced the term delivered-ex-ship (DES), although some parties continue to use the DES reference term.

To determine costs in netback pricing, the following terms are relevant:

- Free On Board (FOB) Pricing: contemplates that the buyer takes title and risk of the LNG at the liquefaction facility and the buyer pays for LNG transportation from the liquefaction facility to the destination market.

- Delivered at Terminal (DAT), Delivered at Place (DAP) and Delivered Ex Ship (DES) Pricing: contemplate that the seller retains title and risk of the LNG until the receiving terminal in the destination market and the seller pays for LNG transportation from the liquefaction facility to the destination market.

- Costs, Insurance and Freight (CIF) Pricing: is a hybrid which contemplates that the buyer takes title and risk of the LNG at the liquefaction facility but the seller pays for transportation from the liquefaction facility to the destination market. The significance of the delivery point is that costs are shifted between the seller and buyer.

The calculation of marine transportation and regasification costs are specific to the ship and receiving terminal to be used.

The destination market pricing is specific to the destination market. For example, US netbacks come from an average of the closing price taken from the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) on the 3 trading days before and including the date reported for delivery at Henry Hub. A local adjustment may be required for pipeline transportation costs depending on the location of the LNG receiving terminal. The calculation of United Kingdom netbacks comes from an average of the closing price on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) futures contract for delivery at National Balancing Point (NBP). Japanese netbacks are derived from the official average ex‐ship prices for the most recent month. A World Gas Intelligence European Border Price table is used to estimate the most recent ex‐ship prices for Spanish market netbacks.

Price Review or Price Re-opener

As previously discussed, unlike crude oil, LNG is not yet priced on an international market basis and most LNG is priced on a long-term basis of 20 years or more. The contractual and confidential nature of LNG pricing, coupled with a lack of transparency of individual cargo prices, means that a wide range of prices might exist even within the same country or region. For example, an LNG contract entered into many years ago may still be in effect under far different pricing structures than those that existed at the time it was first agreed.

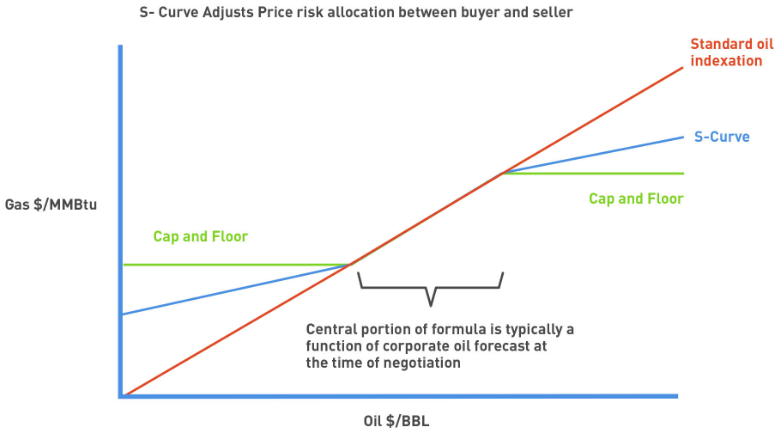

Historically, some Asian buyers have been able to introduce price caps or «S-curves» into their pricing mechanisms, which protect them against very high oil prices and in return, protect sellers against very low oil prices.

An S-curve is so-called because the relationship between the oil price and the gas price is altered to give the seller relief in a low oil price market (a higher price than would apply from strictly applying the oil index – 14 % JCC as an example), and to give the buyer relief in a high oil price market (a lower price than the oil index would generate). Thus in a plot of gas price against oil price, the start and end of the line has a flatter slope than the middle and the resulting line has an S-shape which gives rise to the name. Sometimes, the S-curve approach can be used to derive a price floor at low oil prices, and a price ceiling at high oil prices. The graphic below illustrates a generalized S-curve.

In addition, a price review or price «re-opener» clause is found in many long-term contracts. An example of the language typically used is as follows:

«If . . . economic circumstances in the [buyer’s market] . . . have substantially changed as compared to that expected when entering into the contract for reasons beyond the parties’ control . . . and the contract price . . . does not reflect the value of natural gas in the [buyer’s market] . . . [then the parties may meet to discuss the pricing structure]»

Price review clauses have been a feature of continental European long-term pipeline gas sale contracts for a long time. Lawyers from other regions and legal traditions are often uncomfortable with such clauses because when they are invoked, the parties usually find that their interests are more divergent than expected.

Nonetheless, price review or reopener clauses still remain a key clause of most long-term LNG SPAs and many, if not all, LNG suppliers and buyers enter into negotiations without fully grasping how difficult it is to negotiate such clauses, especially if they are to be enforceable if invoked. As such, the following are key elements that must be addressed with negotiating a price reopener clause:

- The trigger event or conditions entitling a party to invoke the clause must be defined. Usually, this is a change of circumstances beyond the control of the parties.

- The elements of the price mechanism which are subject to review must be defined and usually include:

- The base price.

- Indexation.

- Floor price.

- Ceiling price.

- Inflection points of the S-curve formula.

If a requesting party has satisfied the trigger event or criterion, then there is the challenge of determining which benchmark should be applied to determine the revised price mechanism and often the buyer’s and seller’s view of the relevant market differ significantly. Moreover, since the LNG market is still mostly long-term negotiated contracts that are not public and transparent, the parties may not always be able to access the information and data needed in relation to the broader market for the price-reopener negotiations.

If the parties cannot agree on a revised price mechanism, then the parties should consider referral of the matter to a third-party or arbitration. However, many LNG contracts contain «meet and discuss» price review clauses that do not allow for such referral, leaving the parties without recourse unless some specific recourse is specified. For example, the parties could provide that if the parties are unable to agree on the revised price mechanism, then the seller has the right, upon written notice, to terminate the long-term LNG SPAs.

Recent Pricing Issues

Given the volatility and significant variations in regional gas pricing over the last few years, both LNG sellers and LNG buyers are becoming increasingly focused on how to develop gas pricing mechanisms which give sellers a revenue which reflects the global value of their product, in a manner that will support project development. These pricing mechanisms also provide buyers with a market clearing price, which will enable them to supply gas to their customers at a competitive rate.

With the increasing power of buyers in the currently over-supplied market, new pricing mechanisms are emerging which give the buyer a choice or mix of pricing indices. This new flexibility is sometimes coupled with short-term volume and destination flexibility, with the ability to turn back cargoes that are priced at what the buyer may consider an uncompetitive level.

These increasingly complex price-and-volume provisions are leading sellers to more complex hedging and risk management strategies. New pricing provisions are also supporting the LNG aggregator business model, where an intermediary, either an IOCs or an LNG trading entity, takes on the role of accommodating both buyer and seller pricing concerns and manages a portfolio of gas sources and destinations in order to appropriately manage risk.

LNG pricing formulas are evolving at the moment from pure oil-linked pricing to pure gas-linked pricing, although the full evolutionary process is still underway. As a result, there are various mixed pricing formulas in use at the moment, including pricing techniques that modulate fluctuations in oil pricing, such as an «S» curve which bends the percentage of a crude price at extreme highs and lows.

Another consideration in pricing is the emergence of «pricing review» clauses in LNG SPAs, where the LNG price can be examined and changed at periodic intervals if specified market conditions are triggered. While the intent of these clauses is to preserve a link between a long-term contract and the actual market pricing, such clauses can be very contentious and lead to disputes between sellers and buyers.

LNG and Gas Contracts

Introduction

Gas projects require different types of contracts at different stages of the project development, from upstream to midstream through to downstream. While a significant amount of these contracts are negotiated between private parties, some of the most important ones involve host governments. The ability of governments of resource-rich countries to effectively steward the exploitation of natural resource wealth is predicated upon a number of factors. One of these is the ability to represent the interests of current and future generations in negotiations with private investors and regional partners involved in cross-border natural resources projects.

In that context, an understanding of the different types of contracts, their place in the value chain, and the development of the project, are important. Particular attention should be paid to the technicality and complexity of these contracts. The objective is that governments can prepare effectively for these negotiations, build necessary knowledge to make informed decisions and create dedicated negotiations teams. In addition, contract implementation is equally important and host governments should also build capacity and dedicate resources.

This section aims at providing an overview of the different types and categories of contracts in order to enable governments to prepare accordingly.

PSC v. Licenses

The way in which the upstream contractual arrangements are configured is a complex matter, the basics of which are summarized as follows.

The four contractual structures that have been adopted comprise:

- Production sharing contracts.

- Licenses/Concession.

- Joint ventures.

- Service contracts.

Typically a PSCs would involve lower risk for the investor in that costs are sometimes recovered in a more timely and efficient manner. However, the mechanisms can be complex and entail longer-term risks and cost recovery in economics. In upstream environments that are more stable and sustainable, concessions may offer a better long-term balance.

In the context of LNG projects, the upstream contractual arrangements are not a primary determining factor and have been developed around the world using both primary types of arrangements. Examples of LNG projects under licenses can be found in Qatar, Australia, and the US LNG projects under a PSCs/PSAs can be found in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Angola. Nigerian Australia LNG Export Companies – Infrastructure, Trends, and Future ProjectsLNG projects are based on upstream joint venture arrangements.

Regardless of the upstream structure selected, other legislation (laws), regulations and/or contracts will likely be required for liquefaction and new large-scale natural gas development since many pre-existing host government contracts do not address the specifics of natural gas development. Some of these other contracts are discussed below in the section on Miscellaneous Agreements.

Preliminary Agreements

The negotiation process for the LNG sale and purchase agreement (SPAs) can often be quite lengthy and detailed. Given the multi-year timeframe, it is often necessary to demonstrate progress in the negotiating process. Some sort of preliminary document between the parties is therefore often desired to build confidence in the project and, perhaps, document acceptance of specific terms for the government or the investors’ management.

Preliminary documents can include:

- Term Sheet.

- Letter of Intent (LOI).

- Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

- Heads of Agreement (HOA).

These documents are listed in their progression of detail and completeness, with an HOA typically representing one step below a full definitive agreement, such as an SPAs.

The key issue in all preliminary documents is whether the parties involved are legally bound by the provisions of the preliminary document or whether the parties are still free to negotiate other or different terms, and this may often be a complex matter on which legal counsel would advise. For example, local law may treat some or all of a preliminary document as legally binding even where the preliminary document states otherwise.

Even if a preliminary document is clearly not legally binding, it can lead to disputes if one party later deviates from the provisions of the preliminary document.

Consequently, care should be exercised in entering into any preliminary documents and their use should be limited to only situations where deemed commercially essential.

Domestic Gas Sales Agreement

The domestic Strategic Approaches to LNG Import Project Commercial AgreementsGas Sales Agreement (GSA) follows the typical pipeline gas sales agreement format, with the following key points.

Commitment. The issue is whether the domestic buyer will have a firm « take or pay» commitment under which they are required to pay for supply even if they are unable to accept delivery, or a softer reasonable endeavors commitment. If it is only a reasonable endeavors obligation, the question arises whether the domestic buyer forfeits the right to the committed volumes if delivery is not taken on schedule. By contrast, the LNG plant developer will want to secure gas supply for the liquefaction plant. This includes a take or pay commitment and reserves certification. The commitments of the seller and the buyer should be balanced.

Price. Pricing of natural gas going to the liquefaction plant may depend on the structure of the LNG chain, whether it is integrated, merchant or tolling. The price may be indexed or may be fixed, with or without escalation. If the structure of the LNG export project is integrated, there is generally not a transfer price between the upstream and LNG plant for the gas feeding the LNG plant. Similarly, the domestic gas price can be fixed and/or regulated, or negotiated between buyers and sellers.

Payment. Domestic gas contracts can be priced in the local currency and this can give rise to foreign exchange risk for the investors involved. Payment currency risk analysis should be an ongoing process. Gas sales for exported LNG are typically priced in dollars, however, the trend in domestic gas sales worldwide has been that payment is typically made in the local currency.

Other elements of a standard GSA include:

- Definitions and Interpretation;

- Term;

- Delivery Obligation;

- Delivery Point and Pressure;

- Gas Quality;

- Facilities and Measurement;

- General Indemnity;

- Dispute Resolution;

- Force Majeure;

- Suspension and Termination;

- General Provision;

- Warranty;

- and Indemnities.

LNG Sale and Purchase Agreement

The LNG Sale and Purchase Agreement (SPA) is the keystone of the LNG project bridging the liquefaction plant to the receiving regasification terminal.

Read also: Domestic market for relationships on LNG sales

There is no worldwide accepted model contract for a SPAs, with most major LNG sellers and LNG buyers having their own preferred form(s) of contract. Some international groups, including The International Group of LNG Importers (GIIGNL) and the Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN), have prepared Model Form short-term contracts, e. g. AIPN has a Model Form LNG Master Sales Agreement.

Most LNG SPAs have become lengthy and very detailed documents.

Commitment. The commitment made in a SPA, in its broadest sense, is epitomized by the following statement:

«…the Seller commits to sell and the Buyer commits to purchase …»

The elements of the commitment are term, transportation, volume, level of commitment and ability to divert LNG cargoes.

Term. Historically, LNG SPAs have been long-term contracts with terms of 20-25 years. These long-term contracts were needed by both the seller and the buyer to justify the significant investments required by the liquefaction project and by the receiving terminal and the natural gas end-users. The majority of the throughput of the liquefaction plant needs to be tied into these long-term contracts to enable the developer (see the chapter Financing an LNG Export Project) to secure project finance. As the LNG industry has grown and LNG supplies have become more readily available, there are now some shorter term contracts (5-10 years) for a minority percentage of throughput, but long-term SPAs are needed to underpin financing, described in detail in that section of this book. Additionally, a growing spot market for LNG has developed as a result of several unforeseen factors:

- the development of many global LNG export projects to meet expected US demand (at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s) where the cargoes were subsequently available to other global markets;

- the availability of re-exported LNG cargoes from the US and other countries due to reduced demand.

- the development of tremendous quantities of shale gas in North America and the resulting reversal of a large import destination to an emerging exporter;

- the Fukushima nuclear accident following the 2011 tsunami and earthquake, the consequent increased demand for LNG in Japan and the uncertainty of the timing of the re-start of their nuclear power plants;

- the collapse in oil prices in 2014/2015.

Transportation and Discharge

LNG sales can be done on a FOB (free on board) basis, with the buyer taking title and risk at the liquefaction facility and being responsible for transportation of the LNG; CIF (cost, insurance and freight) basis, with the seller being responsible for delivering the LNG to the tanker at the liquefaction plant. The buyer assumes title and risk, but the seller is responsible for the costs of transportation to the destination or DAT (delivered at terminal) or DAP (delivered at place), with the seller retaining title and risk until the LNG is delivered and the seller being responsible for transportation. The terms DAT and DAP replace the delivered ex-ship (DES) terminology that may still be encountered in some forums.

Volume

The SPAs will specify the volume of LNG that the seller is obligated to deliver, and the volume the buyer is obligated to take, each contract year (generally a calendar year), and provide a process for scheduling and delivering this volume in full cargo lots aboard, agreed upon shipping. The SPA will provide for certain permitted reductions to the committed volume. For example, this would include:

- volumes not delivered due to force majeure;

- volumes not delivered due to the seller’s failure to make them available;

- and volumes which are rejected because of being off specification.

Level of Commitment

It is important to understand the level of commitment being taken on by both the seller and the buyer. If the commitment is «firm», a failure by the seller to deliver or by the buyer to take the LNG would result in exposure to damages. If the commitment is «reasonable endeavors», damages would probably not result.

LNG SPAs are almost always founded on a «take or pay» commitment, where the buyer agrees to pay for the committed volume of LNG, even if it is not taken, subject to the right of the buyer to take an equivalent make-up volume at a later time. Take or pay has been the cornerstone of an LNG SPA since the beginning of the industry and likely will continue into the future. However, some LNG SPAs now use a mitigation mechanism, whereby the seller sells cargos not taken and charges the buyer for any reduction in price, plus the costs of sale.

Similarly, the seller seeks to limit its exposure in a shortfall situation – where the seller does not deliver the full commitment – to something less than full damages. Often the seller will be responsible for a shortfall amount calculated as a negotiated percentage (15 %-50 %) of the value of LNG not delivered, with this amount paid either in cash or as a discount on the next volumes of LNG delivered.

These features, although detailed in nature, can typically involve financial commitments of hundreds of millions of dollars, and are therefore to be negotiated carefully, with the benefit of expert advisors.

Cargo Diversions

Recent LNG SPAs contain the right to divert a cargo to a different market. Where the seller or the buyer diverts a cargo, it is generally done to obtain a higher price. Two key points to address in situations of cargo diversions are the allocation of non-avoidable costs between the parties (e. g. receiving terminal costs, pipeline tariffs, damages for missed natural gas sales) and whether and how the parties should share in the profit obtained through the diversion sale. This later point may entail anti-competition exposure in some countries.

Price

At the time of writing this handbook, LNG pricing formulas are evolving from largely oil-linked pricing to largely gas-linked pricing, although the full evolutionary process is still underway. As a result, there are various mixed pricing formulas in use, including pricing techniques that modulate fluctuations in oil pricing, such as an «S» curve which bends the percentage of a crude price at extreme highs and lows.

One important trend in pricing is the emergence of «pricing review» clauses in LNG SPAs, where the LNG price can be examined and changed at periodic intervals if specified market conditions are triggered. While the intent of these clauses is to preserve a link between a long term contract and the actual market pricing, such clauses can be very contentious and lead to disputes between sellers and buyers.

Technical

Technical provisions to be included in an LNG SPAs include provisions on minimum and maximum specifications for LNG (including heating value and non-methane components), measurement and quality testing of LNG, LNG vessel specifications and requirements, receiving terminal specifications and requirements and provisions for nomination and scheduling of cargos.

Miscellaneous

Aside from the above key components, an LNG SPAs would typically include:

- Provisions for invoicing and payment.

- The mechanism for delivering gas feedstock into the liquefaction facility.

- Currency of payment.

- Security for payment, including prepayment, standby letters of credit and parent company or corporate guarantees.

- Governing law of the LNG SPAs, which typically will be England or New York.

- Dispute resolution through international arbitration.

- Conditions precedent.

- Definitions and interpretation.

- LNG quality.

- Testing and measurement.

- Transfer of title and risk.

- Taxes and charges, liabilities.

- Force majeure.

- Confidentiality.

Miscellaneous Agreements

There are a number of other key agreements that might be necessary for an LNG project, depending on the structure selected. The following is a representative list.

Project Enabling Agreement

Unless specifically authorized by legislation (law) or enabling regulations, a liquefaction project will require some sort of project enabling agreement between the host government and the project sponsors. This project enabling agreement will describe in detail:

- the scope of the liquefaction project to be undertaken;

- the legal regime and the tax regime to which the liquefaction project will be subject, including any tax incentives or exemptions benefiting the liquefaction project;

- the ownership of the liquefaction project, including any reserved local ownership component;

- the governance and management of the liquefaction project;

- fiscal requirements applicable to the liquefaction project;

- local content requirements and procurement procedures applicable to the liquefaction project;

- government assistance including in connection with acquiring land and other licenses and permissions;

- any special local terms and provisions.

Shareholders Agreement(s)

If an incorporated special purpose vehicle (SPV) is to be used, it will be necessary to document the agreement of the shareholders regarding governance and management in a Shareholders Agreement. The Shareholders Agreement complements and expands on the Articles of Incorporation or other constitutional documents of the SPV.

Liquefaction Agreement

If a tolling structure is selected, it will be necessary for the liquefaction tolling entity to have a contract outlining the services to be performed, the tolling fee structure for such services and other provisions regarding risks, etc. with the natural gas customer. This agreement may go by many names, including Liquefaction Agreement and Tolling Agreement.

Gas Feedstock Agreement

If a merchant structure is selected, the merchant liquefaction entity will need to purchase the natural gas to be liquefied in the liquefaction facility. The most contentious issues in the Gas Feedstock Agreement are:

1 the transfer price for natural gas, with the gas seller typically wanting a net-back price and the liquefaction entity wanting a fixed price,

2 and the liability of the natural gas supplier for any shortfall in deliveries, with the gas supplier wanting to limit liability and the liquefaction entity wanting a pass-through of its LNG SPAs liabilities.

EPC Contracts

The engineering, procurement, and construction contract(s) for the upstream facilities and the liquefaction facilities will need to be negotiated and entered into by the appropriate entity, depending on the project structure. See chapter on LNG Development.

Financing Agreements

If project financing is used, a large number of financing and security agreements will need to be entered into.

Transportation Contracts

Either the seller or the buyer will need to contract for LNG vessels to transport the LNG to the market. The options are:

- own the LNG vessels;

- or charter the LNG vessels.

In a vessel-ownership model, an LNG vessel Global Shipbuilding — 2024 Results and 2025 Trendshipbuilding agreement will be required.

A vessel-leasing model will typically be either a bareboat charter (charterer provides crew and fuel), voyage charter (owner provides crew and fuel for a single voyage), or a time charter (owner provides crew and fuel for a set period of time).

Facilities Sharing Agreements (FSA)

This applies to LNG complexes with multiple LNG trains and differing ownership between trains. When any new train is built, in addition to the cost of the train itself, the new entrants are required to enter into facilities sharing agreements. These provide for payment for their share of common facilities, such as:

- LNG storage;

- power generation;

- and LNG berths, etc.

Terminal Use Agreement

In an LNG import project, depending on the project structure, the user of the terminal will enter into a terminal use agreement with the terminal owner. There are a wide variety of titles for this agreement, although they accomplish the same purpose – use of the terminal for a fee.