LNG Project Structures play a crucial role in the successful development and implementation of liquefied natural gas projects. These structures can vary significantly, encompassing integrated commercial frameworks, merchant models, tolling agreements, and hybrid approaches. The choice of project structure often depends on various driving factors, including government policies, market conditions, and stakeholder participation.

- Introduction

- Choosing a Project Structure

- Integrated Commercial Structure

- Merchant Structure

- Tolling Structure

- Hybrid Structures

- Driving Factors on Choice of Structure

- Import Project Structures

- Government Role

- Introduction

- Gas Policy and Regulatory Framework

- National Gas Policy as a Key Enabler for Gas Development

- Features of an Effective Policy and Regulatory Framework

- Elements of a Gas Master Plan

- Domestic Gas Obligation and Local Aspiration

- Legislation and Fiscal Regime

- Principles for Developing Country Hydrocarbon Investment Policies

- Key Elements of A Fiscal Regime

- Institutional Framework

- Stakeholder Participation

- Government Participation

- Roles of Regulator

Effective regulatory frameworks and fiscal regimes also influence how these projects are structured and executed. By understanding the complexities of LNG project structures, stakeholders can better navigate the challenges and opportunities within the gas sector. Ultimately, a strategic approach to project structuring contributes to sustainable development and local economic growth.

Introduction

Natural gas liquefaction projects require considerable capital investment and involve multiple project participants. As a result, the projects typically need to have long, productive lives. Risk needs to be properly allocated and functions for the project participants defined in order to allow debt to be paid off and to generate sufficient returns for investors. Each project would be expected to produce LNG over a period which could span 20-40 years, so it is important to structure the project correctly from its inception to anticipate project risks over time and to avoid misalignments between stakeholders and other risks to the project’s success.

As a result of their high costs, LNG projects are typically executed by joint venture entities with more than one sponsor and with multiple project participants. An appropriate structure will enable entities, often with different aims, such as governments or state-owned entities and private sector companies to comfortably participate in the project. Private sector companies could be energy companies, utilities, and, as is increasingly the case, investors from the financial community. A well-structured project will afford participants sufficient protection in their endeavors. A robust and well-thought-out structure can make provisions for changes to ownership and the future addition of facilities. Indonesia LNG Export Companies – Infrastructure, Trends, and Future ProjectsLiquefaction projects are often expanded via the addition of new LNG trains.

The structure of liquefaction projects will have ramifications for the allocation of risk. The structure can determine whether the sponsors are able to successfully sign sales or tolling contracts with buyers or tolling counterparties. It will also have an impact on whether the project is able to attract further equity investors, if needed, and raise debt funding from financiers. If a project’s structure is weak or overly complicated, the sponsors may struggle to attract buyers for their product as buyers will be evaluating project risk when deciding whether to enter into a sales contract. The structure can impact the financing to the extent that the sponsors may be charged a higher price for any debt that is raised or it may even prevent the project sponsors from attracting funding. These structures may be applied to liquefaction projects utilizing floating liquefaction technology.

LNG import facilities, both land-based and FSRU, will cost less to implement than liquefaction projects, but similar considerations apply. They will often operate over a long timeframe and involve multiple partners.

Choosing a Project Structure

Three basic forms of commercial structures have emerged for LNG export projects – integrated, merchant, and tolling. There are hybrid variations of these three models and the potential exists for further changes in the future. But these three structures are reviewed herein because they are the prevailing structures being used in the LNG industry. There is another option for the host government to fully develop the LNG plant, but this option has had limited application since governments generally do not have the experience or access to the necessary capital.

The selection of a particular commercial structure is a matter of sometimes heated debate and negotiations among the investors in the project and the host government, and the outcome is influenced heavily by the driving factors discussed below. The choice of a commercial structure has a significant impact on the success of the project both in the short-term and over the life of the project. With the wrong structure in place, local investors may not be able to participate in an LNG project and the expansion of the LNG project may be prevented or impeded. Since, ultimately, the government must approve the development under most PSAs/PSCs or licenses, the investor is wise to give consideration to government preferences and engage closely and collaboratively with the government when making key decisions on project structure.

Integrated Commercial Structure

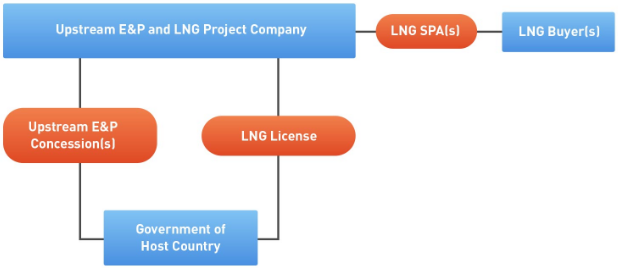

Under the integrated commercial structure, the producer of natural gas is the owner of the LNG export facilities as well as the upstream. The exploration and production project is fully integrated with the LNG liquefaction and export project. The project revenues for both projects are derived from the sale of LNG under one or more LNG sale and purchase agreements (SPAs) entered into by the individual upstream participants or the integrated project company, if one exists. Because the owner of the upstream exploration and production project is the same entity as the owner of the LNG liquefaction and export project, there is typically no other user of the LNG liquefaction and export project. The credit of the LNG buyer or buyers provides the financial underpinning for both the upstream exploration and production project and the LNG liquefaction and export project.

Examples of integrated project structures include:

- Qatar’s Qatargas and RasGas projects;

- Russia’s Sakhalin Island;

- Norway’s Snohvit;

- Australia’s Northwest Shelf and Darwin LNG;

- and Indonesia’s Tangguh.

Merchant Structure

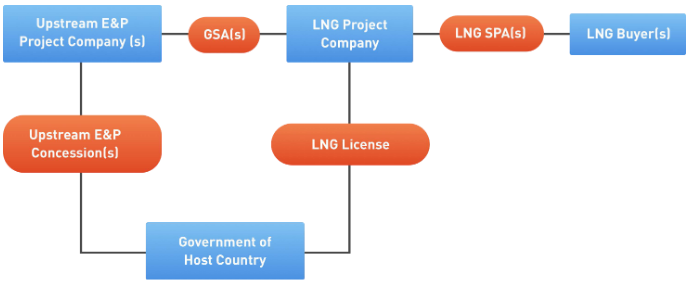

Under the merchant commercial structure, the producer of natural gas is a different entity than the owner of the LNG export facilities, and the LNG liquefaction project company purchases natural gas from the upstream exploration and production project company under a long-term natural gas sale and purchase agreement. The upstream exploration and production project revenues are derived from the sale of natural gas to the LNG liquefaction project company. The LNG liquefaction project profits, in turn, are derived from the amount by which the revenues from LNG sales exceed the sum of the cost of liquefaction (including debt service) and natural gas procurement costs. Because the owner of the upstream exploration and production project is a different entity than the owner of the LNG liquefaction and export project, there may be more than one supplier of natural gas to the LNG liquefaction project company. The credit of both the LNG buyer or buyers and the natural gas producer or producers provides the financial underpinning for the LNG liquefaction and export project.

Merchant structure examples include:

- Trinidad trains 1, 2, and 3;

- Angola;

- Nigeria;

- Equatorial Guinea;

- and Malaysia.

Tolling Structure

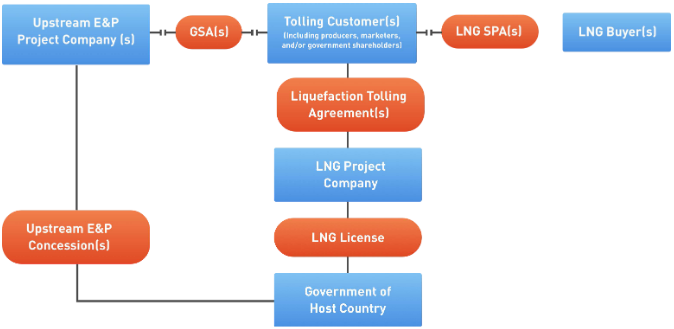

Under the tolling commercial structure – the owner of natural gas, whether a producer, aggregator or buyer of natural gas – is a different entity than the owner of the LNG export facilities. The LNG liquefaction project company provides liquefaction services (without taking title to the natural gas or LNG) under one or more long term liquefaction tolling agreements. The LNG liquefaction project revenues are derived from tariff payments paid by the terminal’s customers. The payments typically take the form of a two-part tariff. Fixed monthly payments cover the project company’s fixed operation and maintenance costs, debt servicing, and return on equity. Cargo payments are designed to cover the project company’s variable costs, such as power. Because the functions of the LNG liquefaction project company do not include a commodity merchant function, the LNG liquefaction project company does not bear commodity merchant risks such as the supply, demand, and cost of natural gas and LNG. The credit of the tolling customer or customers provides the financial underpinning for the LNG liquefaction and export project.

Tolling structure examples include:

- Trinidad’s train 4;

- Egypt’s Damietta;

- Indonesia’s Bontang;

- and the US‘ Freeport LNG;

- Cameron LNG;

- and Cove Point facilities.

Hybrid Structures

Hybrid structures combining some of the attributes of integrated, merchant, and Types of LNG Project Structuringtolling models may be used to tailor LNG liquefaction and export projects to the characteristics and needs of particular host governments and project participants. For example, hybrid merchant-tolling structures have been used in the US by Cheniere’s Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi projects. Here, the project companies provide a marketing service to acquire natural gas and actually take title to the natural gas and sell the LNG to the customer, but also receive fixed monthly reservation charges regardless of whether their customers take LNG.

| Advantages and disadvantages of the different commercial structures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Structure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Integrated | Commercial parties are perfectly aligned between the upstream and LNG liquefaction project No need to determine a | Does not allow for different upstream projects with different ownership to come together in one LNG project Does not allow for other entities, including the host government, to also have ownership in the plant Complex to expand for non-concession production |

| Merchant | Known and commonly used structure familiar with buyers and lenders Flexibility to allow non-concession investors in the LNG plant | Requires additional project agreements with government Potentially different fiscal and tax regime Requires negotiation of gas transfer price |

| Tolling | Known and commonly used structure familiar with buyers and lenders No price or market risk for the LNG project investor | Requires additional project agreements with government Potentially different fiscal and tax regime |

| Government Owned | Owner (government) has full control | Government may lack experience in developing, marketing and operating LNG |

Driving Factors on Choice of Structure

There are a number of key driving factors that influence the choice of an LNG project structure for the host government, the investors, the LNG buyer(s), the project lenders and the other project stakeholders. Some of these key driving factors include:

- Legal Regime and Taxes: The host country legal regime and local taxes often have a major impact on project structure. An LNG project may not be considered as a part of the upstream legal regime in the host country and therefore will need to comply with another legal regime, e. g. general corporate regime, special mid-stream regime or downstream regime. Additionally, the tax rate for the upstream regime may be different (higher or lower) than the legal regime for the LNG project. Both of these factors are considered in selecting a structure.

- Governance: The typical upstream venture is an unincorporated joint venture with the external oversight provided by the host country regulator and internal «governance» provided through an operating committee to the operator, who is generally one of the upstream parties. Day-to-day governance and oversight tend to be less rigid and controlled when compared to an incorporated venture. The government, local stakeholders, lenders and the LNG buyers may desire to have a more direct say in internal project governance and decision making. This needs to be reflected in the structure selected. A poorly governed structure can lead to conflicts among the parties and impact the efficiency and reliability of the LNG Project.

- Efficient Use of Project Facilities: The LNG project structure should encourage efficient use of all project facilities, by the project owners and by third parties. The structure should encourage sharing of common facilities, open access to third parties for spare capacity and reduction of unnecessary facilities and their related costs, thereby making the project more profitable for all stakeholders.

- Flexibility in Ownership: There may be a desire by the government, other local stakeholders, LNG buyers or lenders (e. g. the International Finance Corporation) to have a direct ownership interest in all or specified portions of the LNG project. Alternately, some of the upstream investors may not be interested in owning the liquefaction portion of the LNG project. The choice of a particular structure can enable different levels of ownership in the different components of the LNG project.

- Flexibility for Expansion: A chosen structure may discourage or enable maximum use of common facilities and future expansion trains. For example, an integrated project structure is more difficult to expand if new production comes from third-party gas resources than would be the case with a merchant project or a tolling project. If at some point the upstream does not have enough gas, it may be more difficult to integrate another player with a different gas production model or a different IOCs into an integrated project.

- Desire for Limited Recourse Financing: If the LNG project is going to try to attract limited recourse project financing, a special purpose corporate entity must generally be set up as the finance partner. It is harder to get this sort of project financing with an unincorporated joint venture structure. Consequently, an LNG project looking for financing will typically have a separate corporate structure for the full LNG project or at least for the financing aspect of the LNG project.

- Operational Efficiencies: The integrated structure offers operational efficiencies because only one operator is involved in construction activities. The operational inefficiencies of having two operators can be overcome through transparency and coordination between the operators. Separate projects can lead to project-on-project risk i. e. where one project is ready before the other.

- Marketing Arrangements: The marketer of the produced LNG can be different from the producer, depending on the LNG project structure. The issue is whether there is individual marketing by an investor of its share of LNG production or whether LNG is marketed by a separate corporate entity.

- Regulations: The choice of project structure will affect the required regulations.

- Gas Transfer Price: The gas transfer price is the price of gas being sold by the upstream gas producer to the LNG plant in a merchant structure. This is often a contentious issue, since the major sponsors of the LNG project need to negotiate benefit sharing with the upstream gas producer. In many cases, each segment of the gas value chain may fall under a different fiscal regime. The overall profit of the sponsor may then be maximized by selectively determining where the economic value is to be harvested. When the gas is moved from the upstream (production) to the downstream (e. g. LNG) sector, an «arm’s length» price may be difficult to negotiate. For example, the natural gas production phase of the project may be subject to an upstream fiscal regime which in many countries includes a high tax rate (Petroleum Profit Tax or equivalent). The transportation segment, such as a gas pipeline or conversion of the natural gas to other products such as methanol, usually does not fall under the high tax regime.

Import Project Structures

LNG import projects typically follow the same major project structures utilized with LNG export projects, namely integrated, merchant and tolling. In this context, it should be noted that the Dynamic Simulation and Optimization of LNG Plants and Import TerminalsLNG import terminal itself, whether land-based or floating, can be owned by the LNG import project or leased, often through a tolling mechanism.

- Integrated Structure: the integrated import structure entails the upstream and liquefaction owners extending their reach into the gas market by including a regas terminal. This allows the upstream owners who produce the gas to sell their regasified LNG as gas in a distant market. Examples include the:

- UK’s South Hook LNG receiving terminal;

- Italy’s Adriatic receiving terminal;

- and a number of Japanese and Korean receiving terminals.

- Tolling Structure: in the tolling structure the import terminal provides services, including:

- offloading;

- storage;

- and regasification;

- and charges a fee for such services.

Examples include the US and Canadian import terminals, and Belgium’s Zeebrugge import terminal.

- Merchant Structure: here the owner of the import project buys LNG and sells natural gas, earning a profit on the difference between the price of the LNG and the costs of the import terminal. This structure is exemplified by the various Japanese terminals serving the Japanese utilities.

These structures are discussed in more detail in the chapter on LNG Import Projects.

Government Role

Introduction

In general, the government’s role is to set policies that define development objectives for the gas sector, establish institutions that set priorities, establish legal and fiscal frameworks governing gas and LNG development, and monitor governmental entities and private sector partners to ensure the rules and priorities are followed by all parties during development and operation of infrastructure projects. In some countries, projects are developed and operated by state oil companies, but, typically, LNG projects, whether they are developed by national or foreign investors, require access to specialized knowledge. In some cases, governments also directly participate in developing strategic projects.

Rules, regulations, and procedures should be established, sometimes through the implementation or amendment of legislation or other agreements that have the broad approval of government authorities and its diverse constituencies/stakeholders. Rules, regulations, and procedures should be clear and consistent so that all stakeholders know what to expect from each other. Since it is expensive and difficult to store gas in strategic quantities, plans should also be in place to utilize gas received under domestic supply allocations to promote the development of power and other industrial projects, important for industrialization and job creation.

Gas Policy and Regulatory Framework

Gas development would typically require:

- a national gas policy;

- a gas act or law that provides the overall legal basis for the gas industry;

- a gas master plan that develops an overall plan for gas utilization in the country.

National Gas Policy as a Key Enabler for Gas Development

One of the key challenges in the gas sector is the enactment of effective policies that define policy objectives for the sector and address and help prevent shortfalls in access and supply for both domestic and export markets. The government should provide an enabling environment to promote connecting infrastructure both to meet domestic demand and facilitate export.

Important outcomes that must be generated by a good gas policy include:

- Gas deliverability: the government must ensure that key gas infrastructure across the value chain is properly planned and built in concert with planned power and industrial consumers. This can be achieved via non-discriminatory regulations to enable investment by domestic as well as foreign investors in gas infrastructure.

- Affordability of gas: ensure equitable gas pricing both in the local market and the international (LNG export) markets if necessary to support government priorities. The government should also evaluate the need to establish floor prices to grow the domestic market by incentivizing gas suppliers.

- Commercialization of supply: creating a policy that

- addresses the commercial requirements of gas supply for both local and export markets;

- enables willing buyers to contract with willing sellers;

- allows and protects commercial structures which enable alignment along the value chain;

- facilitates secure offtake with long term back-to-back bilateral contracts that pass obligations and liabilities through to sub-contractors and partners and/or use of integrated business models throughout the value chain with creditworthy parties.

- Availability of gas: balancing available gas resources in line with demand in domestic, regional and international markets and in line with key strategies in the gas master plan.

- Access to market: supporting the right, but not the obligation, to directly access or invest in all parts of the market.

- Regulations: need to be clearly defined and agreed among all parties with regard to issues such as third party access, pipeline ownership, and tariff structures.

The above criteria will set the tone for necessary regulatory and policy frameworks for domestic and export gas supply through the gas master plan as well as the national gas policy. An effective policy and regulatory framework should start with clear objectives as captured in the gas master plan. The plan needs to provide directions for development of the legal and regulatory frameworks via the national gas policy such that the sector can align with gas master plan objectives. The plan needs to allocate gas utilizations across various gas sectors, such as domestic or export, so it can serve as a basis for investment decisions.

Features of an Effective Policy and Regulatory Framework

- Facilitate effective project development/operation for all stakeholders: Both project development and operations for stakeholders are enabled through well-defined government policies and regulations. The government should seek to facilitate participation by local stakeholders such as communities, local government, and other entities.

- Provide transparency, clarity of roles/responsibilities and ease of doing business: Business investment and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows for gas/LNG development are supported by government legislation backing the provision of transparency, clarity of roles and clear responsibilities. The ease of doing business will continue to be a factor for private investment decisions in countries with very large gas resources. It is expected that the government should provide a conducive environment for gas project investment.

- Minimum complexity: A good policy framework requires minimum complexity in term of definition, application and usage. Minimum complexity is achieved when there are clearly defined gas policies that do not contradict or duplicate provisions in other gas documents such as the gas master plan.

- Monetary policy (exchange rate/repatriation of profits, etc.): Government must provide the necessary assurance that movement of profit from invested capital for gas projects or LNG projects are not subjected to restrictions. Repatriation of profits must be allowed if countries want to attract FDI or investors for their gas resource development.

- Facilitate local gas utilization projects: Promotion of critical local gas utilization projects is vested within the gas master plan and is needed to ensure fast acceleration of the domestic gas market. It is, therefore, imperative for government to facilitate local gas utilization programs and policies.

- Facilitate development of local infrastructure, either by government, public/private partnership, or private investors: Regulations should allow multiple options for developing gas infrastructure, either by government, public/private partnership (e. g. build-operate-transfer) or private investors.

- Economic and social development outcomes for local communities: an important consideration for project sustainability.

- Stakeholder consultation: an important role of government is to engage and consult stakeholders in order to take into account their expectations and build a national consensus.

Elements of a Gas Master Plan

The Domestic Gas Infrastructure – Unlocking the Potential of LNG and Gas Value ChainsGas Master Plan falls under the National Energy Policy that aims, among other objectives, to ensure energy security for the country. The elements of a Gas Master Plan may include:

- Objective of the Gas Master Plan.

- Gas resource evaluation.

- Gas utilization strategy and options consistent with country’s energy policy.

- Domestic supply and demand analysis (power and non-power sector).

- Identification of other domestic «priority» projects.

- Infrastructure development plan/formulation.

- Institutional, regulatory and fiscal framework.

- Development recommendations about the volumes and revenues from gas finds and future gas production.

- Identification of possible mega or «anchor» projects. For example, a country with a large natural gas find might consider an LNG export project, or other similar industrial scale plant such as methanol, ammonia production, gas-to-liquids (GTL) projects and dimethyl ether (DME).

- Formulation of a roadmap for implementation of projects.

- Gas sector regulatory reforms.

- Socioeconomic and environmental issues associated with development.

- Gas pricing policy.

Domestic Gas Obligation and Local Aspiration

A tool to ensure appropriate allocations of gas resources for domestic and export use can be the establishment of a domestic gas obligation. Reasonable and equitable domestic supply obligations to promote gas utilization should be carefully specified in the Gas Master Plan and aligned to the country’s national development plan. This should be based on a proper analysis of the national and regional demand for gas together with a plan to develop the transmission infrastructure. The domestic supply obligation (DSO) is a major provision available to countries with gas resources to stimulate the development of the domestic gas market. The policy can allow domestic supply for the needs of gas as industry feedstock as well as fuel for power generation to support the economy. The percentage of DSO varies from country to country and should have the flexibility to allow for any unplanned delay in infrastructure development.

For gas producers to satisfy DSO objectives:

- Mechanisms should be developed to allow for gas producers to meet or otherwise allocate (not meet) their domestic obligations when the infrastructure is not available in their operating area.

- Obligations should be reviewed on a regular basis.

Pros and cons of DSO

Pros:

- A DSO provides opportunities for domestic gas market development.

- A DSO helps to stimulate the economy through provision of energy supply. Energy supply is directly proportional to GDP growth.

- A DSO helps to meet domestic demand of gas-based industries

Cons:

- Depending on the mechanisms adopted, a DSO may constrain the development of a sustainable gas market if the DSO institutionalizes high subsidies or the development of infrastructure that would not otherwise be economic.

- Local obligation supplies often come at the expense of export market revenues.

Legislation and Fiscal Regime

The host Government first needs to define long-term policy objectives for the exploitation of natural gas resources. These could include sustaining government revenues, increasing access to the generation of power, establishing industrial developments, and so on. For investors considering potential investments in the gas/LNG sector of a developing country, a critical element in the investment decision is the country’s hydrocarbon legislation. That legislation creates the legal environment within which investors may explore, develop and produce the country’s hydrocarbon resources.

In some countries, legislation is more general and broad and leaves details of the fiscal, taxation, and other pertinent terms to be addressed in the agreements between the host government and the investors via instruments such as production-sharing contracts or other agreements. In other countries, legislation is more detailed, in which case the agreements may be less comprehensive and still adequately cover the required fiscal and regulatory framework. In cases where the country’s legislation is in early development stage or does not adequately cover the gas/LNG sector, a specific project law is often put in place or the law must be amended in addition to the above-mentioned agreements in order to ensure stability and enforceability of the fiscal and regulatory terms agreed among the government and the investors (e. g. PNG, Qatar, Australia). For LNG projects, such project-specific law authorizes the export of gas as LNG, and facilitates and incentivizes investment in the LNG plant and related export facilities. Regardless of the approach (via a combination of legislation and agreements), the objective is to create a stable and viable investment climate to underpin substantive and continued investments, usually spanning decades, in the country’s hydrocarbon sector.

A number of non-profit organizations have developed guidelines that can be accessed online for policy and regulatory framework formulation. Some of these organizations also provide technical assistance.

Principles for Developing Country Hydrocarbon Investment Policies

The overall fiscal and regulatory structure should begin with an alignment on valuing and recovering resources in a manner consistent with the country’s framework for economic development.

- Create the greatest overall value from the country’s resources by generating:

- Value through the maximum life-cycle economic recovery of resources consistent with the most efficient, safe and environmentally sound development and decommissioning/restoration.

- Growth in local economies as part of value creation via development of local infrastructure, industries, jobs, and training.

- Revenues for the country (including all governmental stakeholders) to reinvest.

- Be equitable both to government and investors:

- Ensure the government, as ultimate steward of the resources, receives for the country an equitable share of the benefit from those resources.

- Provide that investors receive a share reflecting all of their contributions and commensurate with the overall risks they bear.

- Align government and investing companies through project life:

- The regime should be responsive such that equitable sharing of value is realized through all stages of a project life-cycle and across ranges of outcomes and market conditions.

- Recognize that projects and relationships are long-term and thus seek ways to promote partnership and mutual trust.

- Promote a stable and sustainable business environment:

- Country and investors should be able to plan ahead and rely on terms agreed upon.

- Investors should be willing to manage and accept business risks (e. g., exploration, technical, project execution, operation, market, price, and costs) and the country should seek to provide maximum possible certainty on rights and economic terms (e. g., rule of law, contract terms, legal framework, land access or ownership, and fiscal terms).

- Country and investors should operate in good faith to solve potential disputes quickly and efficiently and adopt mutually-agreed dispute resolution procedures, such as mediation and/or arbitration practices, which lead to principles-based, timely resolved and satisfied outcomes.

- Be administratively simple:

- Provide a clear, practical, enforceable, and non-discriminatory framework for the administration of laws, regulations, and agreements.

- Adopt programs promoting cooperation and trust between tax administrators and taxpayers.

- Be competitive:

- Should be competitive with other countries, given the relative attractiveness and risks of resource development.

- Should attract the widest range of potential investors to ensure a country maximizes competition for its resources.

Specific proposals and policies, including the structure and administration of taxation, percentage comprising other government take, and legal requirements, should be tested in terms of whether they further the general objectives above.

Read also: The role of the government in ensuring the development of the gas sector, key factors and principles

Finally, it is worth noting that the overall legal framework of the host country, including bilateral investment treaties, regional and other multilateral treaties and free trade agreements, are all part of the framework within which an agreement between a host country, its broader constituencies, and an investor resides. The legal standing of a contract in relation to a country’s laws is an important consideration. Contract and revenues stability are paramount in establishing a viable investment in gas/LNG, which is generally the case for large-scale, long-term investments.

Key Elements of A Fiscal Regime

The objective of the fiscal regime is to provide a framework for an equitable sharing of revenues between the investors and the host government. The key elements of a fiscal regime governing the exploration, development, and production of a country’s hydrocarbons are covered either in legislation or agreements between the host government and the investors. Such elements may include the following but are not limited to:

- Signature bonuses.

- Production bonuses.

- Royalties.

- Corporate income taxes.

- Sharing of production.

- Special petroleum taxes incentive.

- Custom and import duties.

- Value added tax.

- Pioneer status.

- Tax holiday.

While there are different types of fiscal agreements, such as Production Sharing Contracts and Concession Agreements, the basic objective is the same, which is to provide certainty on how costs are recovered and profits are divided between the host government and the investors.

Institutional Framework

An effective gas industry governance and institutional framework is required to ensure good governance and will be a crucial step to promote investor confidence in the development of gas resources, whether for LNG or for the domestic market. The government needs, through legislation, to define clear institutional arrangements to effectively manage the sector. Particular consideration should be given to clarity of roles among the various institutions. In some countries, there is a need for innovative institutional arrangements or reform. One potential beneficial institution is a one-stop shop for visas, permits, licenses, and approvals. An alternative to a one-stop shop is reform that streamlines these processes. Particular attention should be given to streamlining the number of institutions responsible for:

- managing funding/finance;

- permits and authorizations;

- local content;

- community development;

- sustainability;

- contracts;

- fiscal regimes;

- and regulation.

This requires the government to also clarify roles without merely creating new institutions to compensate for the ineffectiveness of old structures. Requirements for visas, permits, licensing and approval must be transparent for all investors.

Stakeholder Participation

Aligning the interests of stakeholders is a key to the success of any major project. Stakeholders in a project include the host country represented by the Government, as well as potentially by the participation of the National Oil Company, private investors, project contractors, and the local community. The greater the number of stakeholders in the project, the greater the effort that will need to be devoted to ensuring alignment of interests and expectations, and this may lead to complexities, delays and cost overruns. It is, therefore, desirable to manage the number of core project stakeholders to ensure that the project can be developed in a timely manner. Clear policy guidance from the government is also required so all stakeholders understand the basic expectations they should have of the project partners and of local and national government authorities.

The local community generally participates by taking advantage of the opportunity to provide goods and services and by benefiting from training and employment opportunities in the construction and operational phases. The government should ensure that social responsibility agreements and policies are implemented. Local community participation can also take the form of community input generally provided in the regulatory permitting process. On some occasions, if the government and community desire, the community can participate as an investor. In addition to initial input, generally, there are other opportunities made available for ongoing community input at various points, such as at scheduled community forums.

The government also plays a role, in conjunction with the project company, in managing local expectations by providing information on the timing and status of project implementation, from the planning stages on through to final implementation. The government plays an important role through the creation of a national consensus in favor of the project and its implementation.

Government Participation

Strategic government participation in the project is crucial. Government support in many countries is critical to gaining access to land and proper approvals. Government participation in a gas project, especially an LNG export project, may be of significant assistance in all phases of the project, improving project credibility by visibly showing government support, and perhaps also improving alignment along the value chain.

Many governments require government participation in LNG export projects. Government equity participation is generally through the national oil company owning a share in the LNG company that has been established for the project. Some countries also may invest directly in projects without creating a national oil company. Examples include Qatar Petroleum Company (QPC) ownership participation in Qatargas and Ras Laffan Liquefaction (Ras Gas) companies in Qatar and Sonangol in Angola LNG. In these cases, the government entity provides its share of the investment and participates in the financing and profits from operations after the project is completed. Often the government share can be financed by partners but that may also influence the distribution of profits since this carried share must be repaid over time by the government. If the government is unable to pay its share, this can cause misalignment with project partners later in the project. Governments may also receive revenues from the projects through percentages of sales, taxes and/or fees as outlined in the agreements.

For domestic gas and power projects, government investment may also be required to provide an initial platform for subsequent growth. Infrastructure investments such as gas transmission pipelines and gas distribution systems typically require initial government investment, particularly in countries with minimal existing infrastructure. Generally, power generation and electric distribution systems are initiated by government entities. However, some power generation projects, such as IPPs, are done with private participation. When the sector and regulations are more developed, private companies can build and operate whole integrated systems, at which point the government participation may be reduced to regulation and the collection of taxes and fees.

As projects for which government has provided the initial investment mature to the point of becoming economically self-sustaining, there is then the opportunity for the government to divest the project through privatization. However, projects that are subsidized by the government will often require legislative reforms and removal of subsidies before they can be successfully privatized. This is due to the difficulty in attracting private parties to an asset that may not be self-sustaining economically or which might have previously suffered from under-investment.

Roles of Regulator

The government ideally should empower an independent regulator to oversee, supervise, monitor and advise the government on project approval and implementation. The regulator should play a key role in monitoring industry players to ensure that government objectives and established rules and regulations are followed. The regulator may also help to formulate incentives for sector development in coordination with the legislature and other parts of government and would monitor their implementation. A further role may also include the provision of data sources and information as a way of facilitating development within the sector.

The independent regulator should have a role monitoring the sector across the whole value chain. If there are separate regulators for upstream, downstream, midstream, and/or electric power, they should coordinate closely and roles and responsibilities of each should be clear. The regulator often has a role in setting tariffs across the value chain. Tariff formulas must be reviewed frequently by expert staff with sufficient public consultation to account for changes in the market and to allow for the maximum alignment of stakeholders. The regulator may also have a role in setting and monitoring the collection of taxes and fees but the nature and extent of these taxes and fees must be clear and consistent and not arbitrarily or randomly imposed.