The LNG sector is experiencing a significant revival in the Atlantic Basin, leveraging new opportunities and technologies for sustainable growth. This article explores how Qatar is redefining the industry through innovative practices, positioning itself as a key player in the global LNG market.

With a focus on supply and demand dynamics, discover the factors driving this transformative decade for liquefied natural gas. Join us as we analyze the future of LNG and its impact on energy solutions worldwide.

Atlantic Basin enjoys a reviving LNG decade

The Atlantic Basin LNG trades enjoyed a rebirth in 1999, with the commissioning of the first new liquefaction plants in the region in 25 years.

As the 20th century drew to a close the LNG industry was rubbing the sleep out of its eyes and about to embark upon a decade of unprecedented growth. Asia was putting behind it the economic crisis of the late 1990s that had temporarily slowed its strong forward progress and the first new Atlantic Basin liquefaction trains in 25 years were about to be commissioned.

In 1999 the global trade in LNG reached 90,8 million tonnes (mt), 8,4 percent ahead of the previous year. The Asian market, namely imports by Japan, Korea and Taiwan, accounted for 76 percent of the world total. Indonesia was the leading exporter, with:

- shipments of 28,3 mt;

- then Algeria with 18,8 mt;

- Malaysia 14,9 mt;

- Australia 7,1 mt;

- Brunei 6,1 mt;

- Qatar 4,9 mt and Abu Dhabi 4,7 mt.

The LNG trade surge in 1999 was abetted by the commissioning of six new production trains. Three of the units were built for two new Atlantic Basin export projects. The first of the pair opened in Trinidad in July. When the 125 000 m3 Matthew loaded the first cargo, for shipment to the Everett receiving terminal in Boston, it marked the commencement of operations at only the second LNG liquefaction plant in the western hemisphere. North America’s first LNG export terminal, at Kenai in Alaska, had come onstream 30 years earlier, in 1969.

The new US $ 1 billion, one-train, 3 million tonnes per annum (mta) LNG liquefaction plant at Point Fortin in southwestern Trinidad, known as the Atlantic LNG project, still represents the largest, single investment in the Caribbean. It was also the first new, baseload LNG project in the Atlantic Basin in 25 years. With the loading of the Matthew cargo, Trinidad became the world’s 10th LNG export nation.

The inaugural Point Fortin cargo represented the culmination of:

- a six-year programme in which adequate gas reserves were proven;

- innovative contracting mechanisms were employed in finalising gas purchase agreements;

- a greenfield LNG export plant was built;

- and shipping arrangements secured.

The then existing LNG projects had taken, on average, twice that long to bring to fruition. Cabot LNG of the US, the operator of the Everett terminal and a company which had recently been acquired by Tractebel, was contracted to purchase 60 percent of the Atlantic LNG Train 1 output, while Enagas of Spain had secured the remaining 40 percent.

The commissioning of the Trinidad plant, coupled with an increase in demand for natural gas in the US, particularly for power generation, and an increase in US natural gas prices, prompted renewed interest in LNG in that country. Decisions were made to reactivate two mothballed US LNG receiving terminals, Elba Island eventually returning to service in 2001 and Cove Point in 2003.

The increasing demand for natural gas and the availability of adequate gas reserves around the coast of Trinidad had already ensured that Atlantic LNG would not be a single-train operation. Even before Train 1 was commissioned, engineering studies had been completed for two further 3 mta trains at Point Fortin and sale and purchase agreements (SPAs) finalised for their output.

Spain had agreed to buy 3,75 mta of the additional Trinidad LNG and contracts had been put out to tender for four 138 000 m3 LNG carriers to serve this trade. Deliveries were to begin in the first quarter of 2002. Under the terms of a second SPA, for output from Trains 2 and 3, 1,5 mta of LNG was earmarked for the reactivated Elba Island terminal in Georgia. As 1999 was drawing to a close, the partners in the Trinidad project were pushing ahead with plans to market the output from a possible fourth 3 mta train at Point Fortin.

On the other side of the Atlantic the US $ 3,8 billion, two-train Nigeria LNG (NLNG) project finally came onstream in October 1999, some 34 years after it was first proposed by Conch. The 1976-built, 122 000 m3 LNG Lagos departed the Bonny Island export terminal at Finima in Rivers State with the inaugural cargo, for delivery to Montoir in France on behalf of Italy’s Enel.

The other customers of NLNG Trains 1 and 2 were Enagas of Spain, Botas of Turkey and Transgas of Portugal. Over the following years the Enel cargoes were discharged at the Montoir terminal in France due to lack of capacity at Italy’s then only Dynamic Simulation and Optimization of LNG Plants and Import TerminalsLNG import terminal – at Panigaglia terminal near La Spezia. Under this arrangement France made an equivalent amount of pipeline gas available to Italy to compensate.

The original partners in NLNG were the Nigerian government, Shell, Elf and Agip. On commissioning, each of the two trains at Bonny Island had a capacity of 2,7 mta. The growing demand for LNG and the availability of significant gas reserves in the vicinity of Bonny Island ensured that the decision to construct a third train at the terminal was taken six months before the first two came onstream.

In the event the third, similar-sized train was to be commissioned in November 2002, three months ahead of schedule. Once underway, the build-up at Bonny Island was rapid. By February 2001 NLNG had loaded its 100th export cargo and the 400th cargo was discharged at Montoir in September 2003, again by LNG Lagos.

Spain, a major purchaser of LNG from Trinidad and the first two Nigerian trains, also made a major commitment in terms of the output from NLNG Train 3, signing up to take 75 percent of the 2,7 mta that would be produced by the unit. Like their counterparts in Trinidad, the companies behind the Nigerian project were quick to plan even farther ahead, having tabled proposals for Trains 4 and 5 at Bonny before the end of 1999.

In August 1999, as part of the build-up of the fleet needed to carry Nigerian cargoes, Bonny Gas Transport, a subsidiary of Nigeria LNG, ordered two 138 000 m3 spherical tank LNG carriers at Hyundai Heavy Industries. These were the first LNG carriers to be ordered in Korea for foreign owners.

Algeria, the first country to export LNG, also had taken steps to improve its offering to the Atlantic Basin LNG market in the late 1990s. The country’s export volume had dropped to 12,8 million tonnes in 1995 and its ageing production facilities were in need of a revamp. The wide- ranging refurbishment programme implemented by the government in response succeeded in boosting overall production capacity back up to the 21 mta level by 1999. A good level of utilisation was achieved, as Algeria despatched 18,8 mt to customers around the Atlantic Rim and in the Mediterranean over the course of the year.

At the end of 1999 the world LNG carrier fleet stood at 114 vessels while there were 28 ships on order at nine different shipyards. Some of the consultancies specialising in LNG trade forecasting got caught up in the buoyant mood prevailing in 1999 and predicted, in their optimistic case scenario, that there would be a need for a further 100 new LNG carriers over the coming decade, bringing the fleet up to the 250-ship mark by 2010.

In the event the pundits were not optimistic enough, as there were 350 vessels in the global LNG carrier fleet by the end of 2009. To be fair, there was no way of predicting what a topsy-turvy decade it would turn out to be. No one was in a position to fully appreciate either the extent to which the hunger for gas would drive the market or the ability of Qatar’s ambitious export programme to meet that demand. The US shale gas revolution, unforeseen in 1999, turned out to have a bigger impact still.

The Atlantic Basin LNG market did indeed blossom during the first decade of the new millennium. Shipments to the US, Spain and the UK in particular surged and three new liquefaction plants were built – two in Egypt and one in Norway – to help cater for the growing regional demand. Furthermore Qatar brought six new 7,8 mta Super Trains into service and a significant part of the output from these facilities was earmarked for shipment through the Suez Canal to Europe and the US.

The honeymoon was short-lived, however. The exploitation of shale gas resources in the US meant that the country’s imports peaked in 2007, at 16,2 mt, and then fell away sharply. Europe’s imports did not top out until 2011, when they reached 64,8 mt. The continent’s purchases have slumped steadily since then, as the recession following the 2008 banking crisis bit deeply and soaring Asian demand and gas prices sucked available cargoes eastwards. Europe’s LNG imports fell to 33,9 mt in 2013, a nine-year low.

The Atlantic Basin LNG trades over the coming decade will be very much different from those envisaged when the plants in Trinidad and Nigeria commenced operations. The US is poised to become a major LNG exporter while Europe is struggling to rediscover its appetite for LNG. No doubt European imports will revive but, failing a geopolitical crisis of some sort, it will be a long, drawn out process.

Qatar Redefines the Art of the Possible

Qatar started out ambitiously in its drive to provide a world-class LNG delivery capability, and went on to set new standards in LNG production and transport.

Superlatives are required to describe every aspect of Qatar’s involvement with LNG. The country possesses the largest single concentration of gas yet discovered, the North Dome field, and has built the world’s biggest LNG export complex, at Ras Laffan, to bring that gas to world markets.

The cargoes are transported by Nakilat, owner and operator of the world’s largest fleet of LNG carriers. Furthermore that fleet features 31 Q-flex ships of 216 000 m3 and 14 Q-max ships of 266 000 m3, the only LNGCs over 200 000 m3 in size.

Read also: Terminal Operations for LNG or LPG Carrier after Arriving in Port

Amongst the 14 liquefaction units operating at Ras Laffan on behalf of Qatargas and RasGas, the country’s two LNG exporters, are six Super Trains, each able to produce 7,8 million tonnes per annum (mta) of LNG. This is the highest capacity of any such production facility in the industry. Ras Laffan is able to produce an aggregate 77 mta, three times more than Malaysia, its next nearest rival at the top of the LNG exporters league. The port has been operating at, or close to, capacity in recent years, despatching approximately 1 000 LNG cargoes per annum to customers worldwide.

The Gulf emirate’s LNG adventure began in December 1996 when the 135 000 m3 LNG carrier Al Zubarah loaded Ras Laffan’s first export cargo. Al Zubarah is the lead tanker of a 10-ship fleet of spherical tank vessels built to deliver 6 mta of Qatari LNG to Japan over a contracted period of 25 years. Delivered by Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding, Al Zubarah was the 49th LNG carrier to be built to the Kvaerner Moss spherical tank design out of a world fleet of 90 such ships in service at the time.

Chubu Electric signed up for the full output but 2 mta of the total was purchased on behalf of seven other Japanese utility companies. Although this scheme, dubbed Qatargas 1, was the world’s most ambitious LNG shipping project at the time, it represented only the beginning of Qatar’s plans to capitalise on the North Dome gas reserves.

Even before the US$800 million Qatargas 1 grassroots complex, which featured three 2 mta liquefaction trains and three 85 000 m3 storage tanks, was in service another Ras Laffan project had been agreed. In October 1995 Korea Gas Corp (Kogas) signed a contract with Ras Laffan LNG Co (RasGas) for the purchase of 2,4 mta of Qatari LNG for 25 years commencing in 1999, and later exercised an option to purchase an additional 2,4 mta, beginning in the year 2000. The RasGas 1 complex was to feature two 3,3 mta liquefaction trains and two 140 000 m3 LNG storage tanks at the port to service the initial contract levels.

The RasGas 1 project is a 70/30 joint venture between Qatar General Petroleum Co and Mobil. The Mobil share was to become an ExxonMobil share when the two energy majors merged in 1999. ExxonMobil is also one of the shareholders in the Qatargas 1 scheme and was to hold stakes in several subsequent Ras Laffan LNG export projects mounted by Qatargas and RasGas. Qatar Petroleum possesses a controlling share in all the Qatargas and RasGas LNG export projects.

The shipping arrangements for the RasGas 1 project were to be similar to those for Qatargas 1 in that they would be the responsibility of the gas purchaser. In August 1996 orders were placed, against Kogas charters, for six 135 000 m3 LNG carriers at four Korean shipyards:

- Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) was to build two ships for Hyundai Merchant Marine;

- Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME) one ship for Korea Line and one for Yukong Line;

- Hanjin Heavy Industries one ship for Hanjin Shipping;

- Samsung Heavy Industries (SHI) the final vessel for Yukong Line.

The Hyundai ships were built with Moss spherical tanks while the four other ships sported membrane tanks of either the Technigaz or Gaz Transport type. All the vessels were constructed for the then-competitive price of approximately US $220 million each and were delivered over the 1998-2000 period. These RasGas 1 vessels were the first LNG carriers to be built in Korean yards. A seventh Korean-built and operated ship was later ordered to meet the transport needs of the full 4,8 mta Kogas contract.

The RasGas 1/Kogas agreement was inaugurated on schedule in August 1999 when the 135 000 m3 SK Summit loaded the first of 1 900 cargoes scheduled for delivery to the Korean utility over the 25-year life of the scheme.

In those early days Qatar was also negotiating a possible LNG export deal with Enron, the self-styled “world’s first gas major”. Enron was seeking to purchase 5 mta for the Dabhol power plant it was building in India. However, Enron was already running into trouble with the Maharashtra state government over energy pricing, and the LNG terminal adjacent to the power plant was not completed at that time. Enron filed for bankruptcy in late 2001, the biggest collapse in US corporate history.

It was not long before an Indian LNG project did emerge. In March 2001 a third Qatari LNG company – RasGas 2 – was established to supply 7,5 mta of LNG to the Indian utility Petronet for 25 years, commencing in late 2003. RasGas 2 built two LNG production trains, each of 4,7 mta, at Ras Laffan to meet the needs of this new agreement. At the time, the Petronet deal was the world’s largest LNG sale with a single customer, while the two RasGas 2 trains were to be the world’s largest, at least for a short period.

Even then there were no plans to ease back. Qatargas was pressing ahead with a proposal to add a fourth liquefaction train and boost its production capacity to 9,2 mta by 2003. In April 2001 Qatargas announced a one-off deal with Spain for the sale of up to 1,5 mt of LNG, and a few months later RasGas signed a sales agreement with Italy calling for the supply of 3,5 mta of LNG for 25 years to a new offshore LNG receiving facility in the North Adriatic, beginning in 2005.

The latter arrangement represented the first long-term LNG sales contract signed between a Middle East supplier and a European importer. The Adriatic LNG terminal was an offshore gravity-based structure, the industry’s first such facility, and Qatar Petroleum and Exxon Mobil were to become the major shareholders in the venture.

By 2000 LNG shipments to overseas customers of Qatargas and RasGas had climbed to 10,4 mt. Within the space of four years Qatar had become the fourth largest LNG exporter in the world and was achieving annual gas sales revenues of US $2,5 billion. This was only an initial step in the growth curve, however. The country was targeting production levels of 30 mta by 2007, at which point it would be the top LNG export nation and LNG revenues would exceed those from oil for the first time.

The Adriatic LNG project also marked the first in which Qatar was to secure control of the full supply chain, including making deliveries ex-ship. In addition to its majority shareholding in the receiving terminal, RasGas made arrangements to charter four Rules and Regulations for LNGCLNGC newbuildings to transport cargoes to Italy.

Qatar Gas Transport Co Ltd (QGTC), or Nakilat, was established as a joint stock company in 2004 by the state of Qatar to provide shipping and marine-related services, including in the transport of the country’s gas exports. Nakilat took an ownership interest in the four Adriatic LNG ships as well as five further conventional size LNG carriers built for other Ras Laffan export projects. Amongst the marine services provided by Nakilat, in tandem with foreign partners, are a harbour towing and mooring operation and a ship repair yard at Ras Laffan.

Of the 45 Q-flex and Q-max ships mentioned above, 25 are wholly owned by Nakilat and 20 are part-owned. The three Korean yards of DSME, HHI and SHI recorded a remarkable shipbuilding achievement by delivering the full complement of Q-flex and Q-max vessels within the space of 34 months, between October 2007 and August 2010.

The 45 LNG carriers were constructed at a cost of US $12,5 billion and three societies – ABS, DNV and LR – were involved in classing the fleet. The 19 DSME-built ships have GTT No 96 membrane tanks while the eight vessels constructed by HHI and 18 by SHI have Key Characteristics of Membrane Tanks SystemsGTT Mark III membrane tanks.

The Q-flex and Q-max ships, which are all chartered by either Qatargas or RasGas, have enabled Qatar to achieve improved economies of scale in the delivery of LNG to its customers. The four Qatargas and two RasGas Super Trains in place at Ras Laffan have also contributed to this capability. These facilities have built Ras Laffan’s production capacity to today’s level of 77 mta from 14 trains.

The technical management of the 25 Q-flex and Q-max ships fully owned by Nakilat is the responsibility of Shell International Trading and Shipping Company (STASCO). Under the master services agreement signed by Nakilat and Shell, STASCO is assisting the Qatari owner in managing its LNG carrier fleet and recruiting and training seafarers. Further, the partnership agreement calls for Nakilat to assume full responsibility for the management of the fleet within a timeframe of 8-12-years.

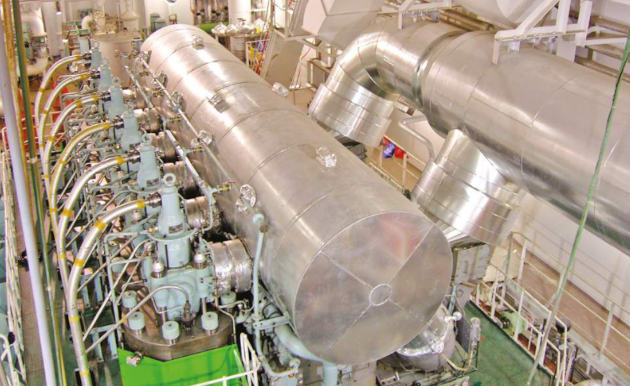

The Q-flex and Q-max vessels were designed and ordered when oil prices were low and those for gas high. The situation resulted in a ship design which is unique for LNG carriers, i. e. a pair of conventional, oil-burning, low-speed diesel engines for each vessel in tandem with a powerful reliquefaction plant which processes cargo boil-off gas and returns it to the tanks as LNG.

Hamworthy provided the reliquefaction plants for the Q-flex ships and Cryostar those for the Q-max vessels. It was decided at the design stage that each of the large ships had to be provided with two reliquefaction plants to provide a full measure of redundancy. Because the reliquefaction plants are computer-controlled when in service rather than operated manually, additional redundancy is provided through back-up monitoring and control systems. For emergencies, to dispose of excess gas if the full cargo reliquefaction capability is down, each vessel is provided with a gas combustion unit (GCU).

All the Q-flex and Q-max ships are built with five cargo tanks, in contrast to the four tanks on conventional size LNG carriers. As many of the conventional size LNG ships now being ordered are of 170 000 m3 and above, there is not much difference in cargo-carrying capacity between an individual cargo tank on one of these ships and one on a Q-flex vessel. Amongst other things, the five-tank arrangement reduces the risk of cargo sloshing damage. The longitudinal strength of the big LNG carriers is such that the ships are capable of handling any combination of full or empty cargo tanks.

As is the case with several of the liquefaction projects at Ras Laffan, the key principals behind the development of the designs for the Q-flex and Q-max ships were ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum. The pair established the Qatargas Operating Company Ltd to oversee the design and supervise the construction of the Q-flex and Q-max fleet. At the busiest time of the newbuild project Qatargas Operating Co had 150 people on its payroll.

Qatargas Operating Co believed that one of the key advantages of providing high-capacity reliquefaction plants for the Q-flex and Q-max vessels was that it disentangled the issue of cargo tank pressures from the ship’s fuel cycle. Nevertheless fuel is the major cost item for Qatargas and RasGas, as charterers of the vessels. Oil bunkers are now expensive relative to natural gas, to the extent that conversion of the existing MAN engines on the Q-flex and Q-max ships to dual-fuel running is being considered.

In 2015, as a test case, the two engines on one of the Q-max vessels will be converted in a project likely to require 40 days in drydock to complete and an expenditure of US $15-20 million. The results of this trial will determine whether the conversion of the whole or a further part of the 45-ship fleet is feasible.

In the meantime most new LNG receiving terminals coming onstream worldwide are designed to accommodate ships of up to the Q-max size and many existing facilities not previously sized for such vessels have now been suitably modified. In recent years one-third of all LNG moving by sea originated in Qatar and in 2013 shipments from Ras Laffan reached 25 of the world’s 29 LNG-importing countries.