Safe working practices at the ship/shore interface (STS Interface) are crucial to ensure the integrity and safety of operations, particularly during the purging of loading arms. The background of these practices emphasizes the need for stringent safety measures to prevent accidents and environmental hazards.

Loading arms must meet general requirements, including proper maintenance and inspection protocols, to ensure their reliability during transfer operations. Specifically, loading arms designed for LPG and liquefied chemical gases require additional safety features, such as pressure relief systems and appropriate materials, to handle the unique risks associated with these substances.

Preamble

In order to avoid confusion, it is necessary to define purging at the outset. In this context, purging means the removal of hazardous material – explosive and flammable gases, vapours, and liquids – from a space and replacing them with an inert or safe atmosphere of gas.

The concept of purging being a process which culminates in safe atmospheres is familiar to the seafarer. The purging of void spaces for entry or the purging of boilers before a relight are examples. However, in relation to liquid gas carriers, purging can have a different meaning. The first edition of SIGTTO’s textbook, Liquefied Gas Handling Principles, used the following definition: Purging (or «gassing-up»): to replace inert gas in the cargo tanks, etc. with vapour of the cargo to be loaded.

In order to correct this bewildering situation, the recently revised second edition of the textbook refers to the process of replacing an inert atmosphere with cargo vapours only as «gassing-up» – not as purging. It is recommended that the word purging is no longer used to describe gassing-up operations and that it is restricted to describing processes which make for less dangerous or completely safe spaces.

Background

Discussion amongst SIGTTO members concerning loading arm operations drew attention to the fact that LNG terminals have a limited number of LNGC classes and a single product to handle. On the other hand, LPG and Chemical Gas trades often share terminal facilities and cope with many different types of LPGCs as well as a variety of cargoes. Under these circumstances, procedures for working at the ship/shore interface must be clear and concise for those teams who may be meeting for the first time and who indeed may never work together again.

It was thought that, by concentrating upon purging procedures and the coupling/decoupling process, and circulating the general principles of such critical operations, safe working at LPG/Chemical Gas terminals could be sustained and improved. This Information Paper No.16 is the result of these deliberations.

Loading arms – general requirements

OCIMF’s Design and Construction for Marine Loading Arms gives guidance on how arms shall be purged. They state the following, which is applicable to arms conveying liquefied gases:

Purging Systems

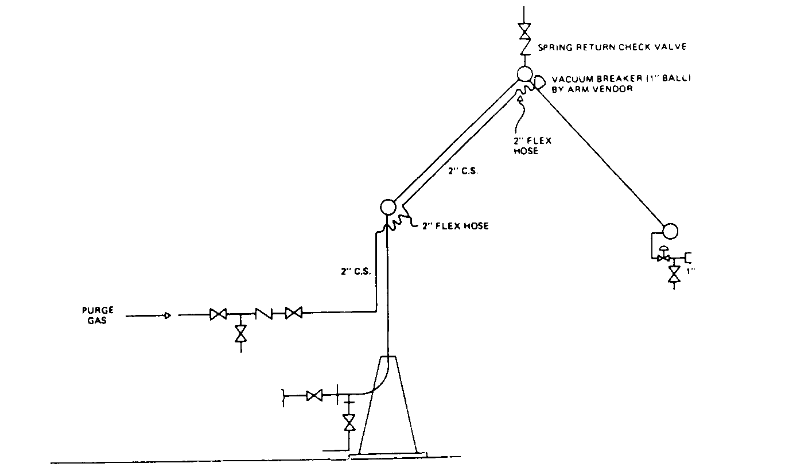

Purging systems are also used for either normal or emergency draining operations. The LNG Transfer Arms and Manifold Draining, Purging and Disconnection Procedurepurging of the arms is accomplished by injecting the purge medium into the outboard arm just past the apex joint. The product is purged from the outboard arm into the tanker and from the inboard arm and riser to the shore piping system. A typical scheme is shown in Figure 1.

Depending on the intended usage, the sequence of operations may be manual or automatic. In general, highly volatile products must be purged with nitrogen.

SIGTTO’s textbook Liquefied Gas Handling Principles on Ships and in Terminals gives operational advice based on the OCIMF concept:

Towards the end of the loading operation, loading rates should be reduced to an appropriate rate as previously agreed with shore staff in order to accurately «top-off» tanks. On completion of the loading operation, ship’s pipework should be drained back to the cargo tanks. The liquid remaining can be cleared by blowing ashore with vapour using the ship’s compressor or by nitrogen injected into the loading arm to blow the liquid into the ship’s tanks. Once liquid has been cleared and lines depressurised, manifold valves should be closed and the hose or loading arm disconnected from the manifold flange.

On completion of cargo discharge, liquid must be drained from all deck lines, cargo hoses or hard arms. This can be done either from ship to shore using a cargo compressor, or from shore to ship, normally by blowing the liquid into the ship’s tanks using nitrogen injected at the base of the hard arm for example. Only after depressurising all deck lines should the ship/shore connection be broken.

As can be seen from the foregoing, after cargo operations have been completed, the loading arm contents will be either cargo vapour or nitrogen.

Loading arms for LPG and liquefied chemical gases

In order to give practical guidance, the description of loading arm operations are illustrated by reference to actual instructions provided by LPG/Chemical Gas Terminal Operators to ships working cargoes at their facilities.

Ship/Shore Information Exchange

The advice given in this section should be augmented by reference to SIGTTO’s Information Paper No.5: The Ship/Shore Interface – Communications Necessary for Matching Ship to Berth.

Before arriving at a terminal, it is necessary to establish that the ship can safely handle cargo using the terminal’s installed equipment. Particular attention is paid to the ship’s manifold/loading arm match and the mooring arrangements. It is recommended that this work is done long before the vessel comes alongside in a dialogue between Owners, Charterers and Terminal management.

Upon arrival, the terminal operators board the gas carrier and seek confirmation from the master that the information they have concerning his ship is correct and that he understands the essential features of the terminal installation. A record of the information exchange is retained both by the ship and by the terminal staff. A typical set of documents which serve this purpose are contained in Appendix 1.

Appendix 1

At the same time, the terminal management will establish their position with regard to safety policy. In the case of the organisation which supplied the detail for Appendix 1, this takes the form of handing the master a letter explaining both parties’ responsibilities and obligations. They also provide a ship/shore safety check list and a smoking notice. All documents have to be countersigned by the master or a representative of the master, i. e. chief officer, and a representative of the terminal management. Examples of these papers are contained in Appendix 2. Some terminals produce instruction manuals for this purpose.

Appendix 2

Dear Sir,

Responsibility for the safe conduct of operations on board your vessel whilst at our terminal rests with you as Master. Nevertheless, since our personnel, property, other shipping and port facilities may also suffer serious damage in the event of an incident on board we wish to seek your full cooperation and understanding on the Safety Requirements set out in the Ship/Shore Safety Check Lists.

These safety requirements are based on safe practices widely accepted by the oil and tanker industries. We therefore expect you and all under your command to adhere strictly to the requirements throughout your stay alongside this terminal. We for our part will ensure that our personnel do likewise and cooperate fully with you in the mutual interest of safe and efficient operations.

In order to satisfy ourselves of your compliance with these requirements we shall, before operations commence and thereafter from time to time, instruct a member of our staff to visit your vessel. After reporting to you or a nominated Deputy, he may ask to join one of your Officers in a routine inspection of cargo decks and accommodation spaces.

Should any infringement of the requirements be observed on board, we shall immediately bring this to your attention and we expect corrective action to be taken. If such action is not taken in a reasonable time, we shall adopt measures which we consider to be the most appropriate to deal with the situation, notifying you accordingly.

Should you or your staff observe any infringements by Terminal personnel, whether on the jetty or on board your vessel, please bring this to the notice of our representative nominated as your contact throughout the stay of the ship. Should you feel that any immediate threat to safety arises from any action on our part, or from equipment under our control, you are fully entitled to demand an immediate cessation of operations.

IN THE EVENT OF CONTINUED OR FLAGRANT DISREGARD OF THESE SAFETY REQUIREMENTS BY ANY VESSEL WE RESERVE THE RIGHT TO STOP ALL OPERATIONS AND TO ORDER THAT VESSEL OFF THE JETTY TO ENABLE APPROPRIATE ACTION TO BE TAKEN BY THE CHARTERS AND OWNERSCONCERNED.

Please acknowledge receipt of this letter by signing and returning the attached copy.

| On behalf of the Terminal | On behalf of the Ship Receipt of this letter is acknowledged | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signature | – | Signature of Master | – |

| Name | – | LPG Carrier | – |

| – | Date and Time | – | – |

CALOR Gas Felixstowe Terminal

| Ship/Shore Safety Check List | |

|---|---|

| Ship’s Name: | |

| For Ship | For Terminal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Is there safe access between ship and shore? | ||

| 2. | Full information on the ship/shore cargo transfer connection has been supplied and the extreme positions of the Marine Loading Arm (MLA) operating envelope have been plotted on the diagram supplied. Are you satisfied that a safe connection has been made? | ||

| 3. | Has the Terminal’s portable VHF radio set been supplied/tested and are the agreed methods of communication fully understood? | ||

| 4. | Is the ship ready to move under its own power at short notice? | ||

| 5. | Are smoking, naked lights and galley restrictions in force and being observed? | ||

| 6. | Are all torches, portable VHF sets, etc., of an approved type for use in hazardous atmospheres and is all portable electrical equipment isolated? | ||

| 7. | Are ship’s main transmitting aerials switched off and earthed? | ||

| 8. | Is the ship’s firefighting main pressurised or ready for immediate use and is the water spray protection ready for immediate use? | ||

| 9. | Are fire hoses and firefighting equipment on board and ashore ready and positioned for immediate use? | ||

| 10. | Are void spaces correctly inerted and/or isolated from cargo systems? | ||

| 11. | Are ventilation systems and positive pressure protective systems functional? | ||

| 12. | Are all ports and external doors closed and are air conditioning intakes designed to prevent the ingress of cargo vapours? | ||

| 13. | Are all cargo transfer valves and remote control valves sound and fully functional? | ||

| 14. | Are all cargo tank relief valves correctly set and functional? | ||

| 15. | Are the required cargo transfer pumps, compressors and reliquefaction units functional? | ||

| 16. | Is the fixed gas detection system correctly set for the cargo being carried, calibrated and in good order? | ||

| 17. | Are all cargo systems gauges and alarms correctly set and functional? | ||

| 18. | Are ali unused cargo, ballast and bunker connections fully blanked off with suitable drip trays in position? | ||

| 19. | Are the Emergency Shut Down systems both ashore and on board fully functional and has information concerning valve closure times been exchanged and the discharge rates agreed? | ||

| 20. | Is there an effective deck watch in attendance on board and adequate supervision on the terminal, jetty and shop? | ||

| 21. | Are sufficient personnel on board and at the terminal to deal with an emergency? | ||

| 22. | It is strongly recommended that a lifeboat on the offshore side be swung out and lowered to embarkation level to provide means of emergency escape. Is this being done? | ||

| 23. | Is sufficient and suitable Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) available for immediate use? | ||

| 24. | Has information on cargo quality and quantity been exchanged? | ||

| 25. | Is the ship securely moored and are towing off wires positioned correctly? | ||

| 26. | Are the ship and jetty hazardous warning lights on and functioning? | ||

Declaration

We have checked, where appropriate jointly, the items on this Check List and have satisfied ourselves that the entries made are correct to the best of our knowledge and that arrangements have been made to carry out repetitive checks as necessary.

| For Ship | For Terminal | Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Name | |||

| Rank | Position | Time | ||

| Signature | Signature | |||

One aspect of these early exchanges concerns the language to be used during the cargo handling period, when ship and shore are actually working together. Obviously, if shore and ship personnel share a common nationality there is no problem. However, as more and more ships are staffed by an ever increasing diversity of nationalities, understanding at the ship/shore interface becomes progressively more difficult.

At the time of completion of the Check List, both ship and shore must demonstrate that they have sufficient numbers of key personnel who can communicate clearly and accurately for both routine and emergency situations throughout the period the vessel is alongside. If the parties concerned do not have a common language, it is preferred that they use English when working together.

Most terminal instructions to ships’ staff clearly define who is required to perform those routine tasks associated with cargo movements. As far as possible the work is split into separate tranches, the performance of which becomes the responsibility of either ships’ personnel or shore operators. In this way the need to work directly together is held to a minimum, offering the least opportunity for misunderstanding.

Instrument checks during loading and discharging

When considering operational practice, the differences between LNG and LPG are marked. LNG is essentially a single product trade with a limited cargo volume range between vessels. LPG and Environmental management of ships during transportation of LNG/LPG gaseschemical gases are materials having widely different properties and parcel sizes. At times, the liquefied petroleum and chemical gases share facilities handling other bulk liquids. Table 1 illustrates both the variety of products which can be handled in such a port and the physical conditions under which they are held.

| Table 1. Example of Product Loading Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Product | Temp Range °C | Max Pumping Pressure |

| Crude oil | 10/30 | 4,5 |

| N-BUTAN Pressurised | 0/20 | 7,72 |

| Refrigerated | 0 | 3,6 |

| Spiking crude | 0 | 10,4 |

| ISO-BUTANE Pressurised | -11/20 | 8,77 |

| Refrigerated | -11 | 3,3 |

| Spiking crude | -11 | 10,4 |

| PROPANE Pressurised | -10/16* | 20,3 |

| Refrigerated | -42 | 2,8 |

| Blower Return | – | – |

| ETHANE Refrigerated | -90 | 5,7 |

| Blower Return | – | – |

| BUNKERS Diesel | Ambient | 4,0 |

| *Proven minimum limit – 11,5 °C | ||

| This data pertains only to the port in question and results from the process that manufactures these export products. They do not in any way represent any standard for conditions of storage and handling. | ||

Despite these differences, the work methods employed at the LPG ship to shore interface have much in common with LNG arrangements.

As an example, the procedures set out below are given for a twin jetty liquefied gas export facility situated in Scotland, handling liquefied propane, butane and ethylene.

Operational procedures

The Terminal Staff will be responsible for connecting/disconnecting loading arms/hoses to the agreed ship’s presentation flanges as indicated by the responsible ships officer.

The Loading Arms are normally purged and remain under Nitrogen between loading operations. Vessels must, therefore, be prepared to receive a small volume of Nitrogen vapour at the commencement of loading operations. (0,5 m3 at the East jetty, 10 m3 at the West jetty).

With regard to the second paragraph, gaseous nitrogen (GN2) is less of a problem for LNGCs when it enters the cargo spaces than it is for fully and semi-refrigerated LNGCs. In the case of the latter, it affects the refrigeration systems by increasing the non-condensible element which in turn reduces the efficiency of the refrigeration plant. For LNGCs, nitrogen in the boil-off gases (BOG) merely affects the calorific value of BOG when it is burned under the ship’s boilers.

However, it would appear that this practice is acceptable to ship operators at this particular LPG ExportTerminal. The instructions continue:

- The responsible terminal representative and ship’s officer will agree that systems are correctly lined up before transfer operations begin.

- The terminal staff will pressurise the loading arm with Nitrogen against the ship’s manifold valve and the loading arm connection will be tested for leaks. When manifold has been proven «tight», the loading arm will be depressurised and transfer commenced at the agreed starting rate.

- Loading must be commenced slowly to avoid rapid pressure build up.

- When liquid flow is established, the terminal will increase rate as requested by the ship, up to the agreed maximum bulk rate.

This particular port does not seek to purge out air and check for oxygen levels since it is normal to maintain an atmosphere of GN2 during those periods when cargo is not being transferred.

When loading is completing, at least 15 minutes’ notice must be given of transfer rate changes. A typical subsequent sequence of events is given below:

After loading has stopped, all arms must be cleared of product and vapour by nitrogen purgingbefore being disconnected.

1 Confirm the following:

- Loading has stopped.

- Jetty motor operated valves (MOVs) open.

- Ship’s liquid and vapour manifolds closed.

- Surge drum dump valves open.

2 Set nitrogen pressure controller to 2,0 bar(g).

3 Connect nitrogen hose to base of stand pipe on selected loading arm and slowly open the nitrogen valve.

4 Allow nitrogen to purge gas out of the arm back to the surge drum for 5 minutes, then close the nitrogen supply valve.

5 Close MOV on line being purged.

6 With nitrogen pressure still set at 2,0 bar(g), re-open the nitrogen supply valve on the arm to be purged.

7 Allow nitrogen pressure to reach 2,0 bar(g) in the arm being purged then shut off nitrogen supply valve.

8 Request ship to open manifold valve on arm connected to line being purged.

9 Purge to ship until pressure in loading arm is zero then close Manitold.

10 Steps (6) to (9) will normally be repeated two or three times to clear liquid cuty loading arms.

NOTE: Each ship will need to be considered separately for the pressure set, i. e. ships with Cargo pipework below the connected flange level will purge clear with a pressure of 2,0 bar(g) or less whilst others, where cargo pipework is higher than the manifold will require a pressure of up to 3,0 bar(g).

11 To check that the arm is successfully purged, ensure that all personnel are standing clear and carefully open the drain valve at the base of the triple swivel joint.

12 Leave drain valve at base of arm open.

13 Repeat above steps (1) to (12) in sequence for each arm.

14 Nitrogen hose to be disconnected after use to ensure positive isolation.

After this process has been completed the arms are disconnected. This procedure gives no instruction for checking the arms for hydrocarbons in the internal nitrogen atmosphere. The process is regarded as being sufficiently reliable to assume all hydrocarbons have been swept clear of the arms.

Purging with nitrogen is not always required. In the LPG trades, as SIGTTO’s Liquefied Gas Handling Principles states, «The remaining liquid can be blown ashore with vapour using the ship’s compressors….». Recent enquiries indicate that, despite having GN2 available on the jetty, one organisation uses warm gases in the manner described.

Checks to ascertain that lines are liquid-free, involve cracking open the drain valves at the base of the swivel joint on the loading arm being purged. The type of effluent from the drain will indicate if any liquid remains. When no liquid is detected, the arm is isolated and the pressure within gently released before the arm is disconnected from the ship’s manifold.

There are some limitations to this practice. if cargo vapours used in purging have a low degree of superheat and/or lines to be cleared are at all long, then cargo vapours will tend to condense; the purging process is thus rendered ineffective. In general terms, vapours generated from fully-refrigerated and semi-pressurised cargoes will possess sufficient superheat to be able to avoid condensing. However, as pressures rise and ambient temperatures approach the vapour saturation temperature, the risk of condensing increases.

This practice inevitably releases some hydrocarbon when ship and shore are disconnected. Whether such a procedure will be permitted in the future is open to question. Alternatively, GN2 can be used such that only GN2 is released when decoupling.

Again, no tests are required since the sequence followed in no way permits anything other than atmosphere of hydrocarbon vapours and gases to develop.

Taking another example, the port in Northern England, whose export products are listed in Table 1, gives general guidance that the ship’s tanks are to be purged of air prior to loading. For this port, terminal representatives will be satisfied if the oxygen content of tank atmospheres does not exceed 5 % by volume. Crude oil and other oil products are loaded over jetties within this establishment. Terminal requirements, therefore, simply reflect tank atmospheric conditions which competent oil tanker operators set for themselves. In this particular situation, the port authorities wish LPGCs to perform to the same limits.

The prescriptive nature of this local rule implies oxygen readings from tank atmospheres will be taken before loading begins. Measurements will probably be undertaken by competent terminal personnel accompanied by ship’s staff.

With regard to disconnecting loading arms, the port instructs as follows:

- Cargo loading arms to be completely cleared of liquid and all pressure removed before disconnecting.

- Nitrogen is connected to the loading arms for purging prior to removal of the arms.

Again, no request is made to check for hydrocarbons in the nitrogen atmosphere. No doubt the same reasons hold good as those given for the first example of terminal operations – namely that the GN2 purge process will not permit any significant hydrocarbon vapours and gases to remain in the loading arms.

Purging of lines from the loading arms back to storage does not occur at most LPG terminals. In general, propane from fully-refrigerated storage will quickly evaporate, ending as vapour in the storage vapour spaces. Butane, under similar circumstances, will not evaporate at anything approaching the rates propane achieves and will frequently form pockets of liquid which have an appreciable life expectancy.

Other instrument checks made at, and adjacent to LPG/chemical gases shore manifolds

LPGCs are capable of carrying a variety of different cargoes. In this, they are far more flexible than the single cargo LNGCs, some of which do have scantlings permitting the carriage of LPG. However, very few have ever been engaged upon such trade.

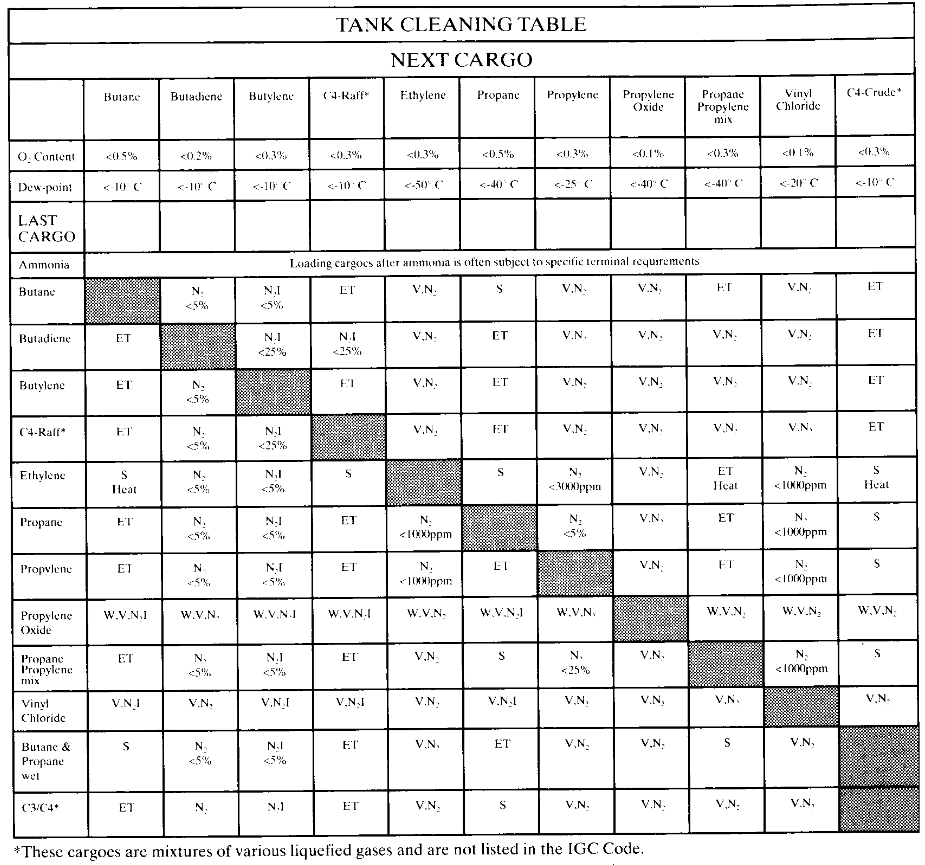

Table 2 shows different cargoes which can be carried by LPGCs and illustrates typical loading conditions which avoid contamination when switching from one cargo to the next.

Table 2 shows that for a ship to present itself to a terminal in a fit state to cope with a cargo change, quantitative measurements of Cooldown of Cargo System on the Liquefied Gas Carrierscargo system atmospheres are frequently required.

| CODE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| W | Water wash |

| V | Visual Inspection |

| N2 | Inert with Nitrogen only |

| N2I | Inert with Nitrogen or Inert Gas |

| ET | Empty Tank: which means as far as the pumps can go |

| S | Standard Requirements: cargo tanks and cargo piping to be liquid free and 0,5 bar overpressure (ship-type dependant) prior to loading, but based on terminal or independent cargo surveyor’s advice. |

| Note. Before any inerting starts the tank bottom temperature should be heated to about 0 °C. Note: A cargo tank should not be opened for inspection until the tank temperature is close to ambient conditions. | |

To make measurements such that conditions specified in Table 2 can be achieved, the instruments listed in Table 3 will be required:

| Table 3. Instruments for LPG cargo operations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measured gas, liquid or quality | Atmosphere in which measurement is made | Typical measuring instruments currently in use |

| O2 % by vol. | N2 | O2 meter Servomex 570A Servomex 262A Keiki OX227 Riken NKE252B MSA O2 meter Draeger O2 meter Gas/O2 Riken Keiki GX85N |

| Liquid presence | N2 | Visual |

| LPG | N2 | Industrial Scientific CMX270 Tankscope Riken Keiki NP273H Riken Gas Indicator Type 1B Riken Keiki GX85N & GX-7 Keiki Interferometer MDD 17M |

| Dewpoint | Air | Shaw award Dewpoint Meter Type 1-2 Shaw award Dewpoint Meter Type S.A.D.P. Alnor Dewpointer 7000 U Mini-Thermohygrometer (digital) TESTO 610 |

| Dewpoint and O2 | Inert Gas | As for Dewpoint As for O2 |

| NH3 | Dry Air | Draeger Multi Gas Detector 21/31 |

| Chemical gases | N2 | Draeger Multi Gas Detector 31/31 |

Paradoxically, although more measurements are required when working LPG and chemical gas cargoes, these tend not to be made at the loading arms or the manifold spool pieces during the actual cargo transfer operations.

Read also: Cargo Handling Systems and Specialised Equipment on LNG LPG Carriers

A typical practice for a vessel presenting to transfer cargo would be for the shore side to take samples of the cargo or tank atmospheres for detailed analysis. These would usually be made by cargo surveyors, subsequent cargo movements would be dependent upon the outcome of these checks. However, once the transfer operation is set in motion, measurement of atmospheres in ship’s piping and shore loading arms does not occur. The process is such that it is assumed the contents of these systems can only be liquid cargo, cargo vapours, N2 or a combination of all three. Apart from checking that liquids have been removed, no other measurements are taken.

Commentary on comparison of purging systems

Cargo sampling apart, the practice of taking actual measurements during loading arm operations seems to be restricted to the transfer of LNG rather than LPG/liquefied chemical gases.

For all intents and purposes, LNG transfers take place with no release of NG at all, either in the gaseous or liquid form. If proof of this condition is required, measurements should be taken which record and substantiate this work practice.

For LPG/liquefied chemical gas cargo movements which involve GN2 purging, the same claim can be made, although general practice does not require records to prove there have been no releases.

For LPG/liquefied chemical gas cargo movements which use warm gases as the purge medium, release of some gases or vapours into the atmosphere is unavoidable. Eventually, this practice may become unacceptable to regulatory authorities.