Bunkering Facility Development is essential for ensuring that fuel supply operations meet regulatory and environmental standards. This process involves navigating complex state, provincial, and local regulations to secure the necessary approvals.

Additionally, effective bunkering facility development requires addressing infrastructure needs, such as port facilities and logistical support, to enhance operational efficiency. Engaging in a thorough consultation and coordination process with stakeholders is crucial for aligning interests and facilitating smooth approvals.

Process for Gaining Approval of a Proposed Bunkering Facility

The LNG industry gained a great deal of experience in attempts to get import terminals licensed and approved in the last decade. LNG bunkering facilities are much smaller investments, smaller facilities, and present lower impacts on communities, both in normal operation and if accidents occur. However, some of the same lessons learned in the approval process for import terminals can be applied to bunkering facilities.

Early leaders in developing Developing LNG Bunkering Facilities in Ports: Governance and Good Practicebunkering facilities are already sharing their recent experience in dealing with regulators and local communities. This section: (1) outlines some of those lessons learned, centering on the federal, state, tribal, and local agencies and organizations with whom coordination may be required (See below) and (2) provides suggestions on how to properly coordinate and communicate (See below). First, however, the following describes some of the unique aspects of bunkering facilities that help shape the approach a bunkering project developer needs to understand.

Regulatory Requirements. Considering regulatory requirements, LNG bunkering facilities have both an advantage and a disadvantage compared to large import or export facilities when it comes to obtaining approval to build and operate a facility. The FERC approval process for LNG import or export facilities can take 1 to 2 years to obtain construction license approval. The FERC approval process does not apply to bunkering facilities. That advantage comes at a price because the regulatory process for the first wave of LNG bunkering facilities is not nearly as well defined as the FERC process. On balance, it seems the flexibility and shorter time frame is a positive for companies that want to develop bunkering facilities. See below documents the types of agencies and permits that will be required to gain formal approval of onshore LNG bunkering facilities. See below outlines considerations for developers as they seek project approval, with the primary strategy being the consultation and coordination required by the project to replace the structured process that FERC uses for import and export facilities.

Lack of Federal Pre-emption. Earlier sections of this study outlined the current status of regulations that are «potentially applicable» to bunkering facilities. Some of them are in draft form and others have policy or guidance under which they will be developed and have not yet been drafted as regulations. This lack of maturity is compounded by the lack of an overall regulatory framework like FERC provides for import and export facilities. As described in the FERC docket for a facility under review, FERC reviews inputs and questions from other federal, state, tribal, and local agencies and organizations. Although somewhat cumbersome, under the Natural Gas Act (NGA), the FERC authority pre-empts the ability of states to disapprove LNG facilities except under specific circumstances defined in the NGA (e. g., if a facility does not adequately satisfy the Coastal Zone Management Act). That pre-emption policy does not apply to LNG bunkering facilities. Developers will have to identify all of the applicable regulations for the specific location, including:

- federal;

- state;

- tribal;

- and local requirements and make sure they are satisfied.

The resources in Chapters LNG Bunkering Guidelines: Comprehensive Insights and Best Practices for OperatorsGuidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators, LNG Bunkering Guidelines: Comprehensive Insights and Best Practices for OperatorsGuidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators, and LNG Bunkering Guidelines: Comprehensive Insights and Best Practices for OperatorsGuidelines for Bunkering Facility Operators of this study help identify federal regulations that apply to gas-fueled vessels, LNG bunkering vessels, and LNG bunkering facilities, respectively. However, that information does not represent all of the requirements that are dependent on the specific location of the bunkering facility and the actual bunkering activities. Again, effective coordination and consultation with appropriate stakeholders are essential.

Risk Perceptions. It is clear that some earlier LNG facility development projects have faced increased costs and delays because of local opposition, some of which is based on perceptions of the risk from LNG that are not realistic. LNG bunkering facilities need to be prepared to address these issues as well, although arguments can be made that the smaller facilities involved in bunkering do not pose similar risks. The primary way to address misunderstanding of risks is to facilitate two-way communication with stakeholders that have concerns and with those that have not yet decided how they feel about an LNG facility in their community. See below addresses communications needs and approaches for LNG development activities.

Awareness of Jurisdictional Bans. The only known, specific ban of LNG activities by a North American city or state is the moratorium on LNG storage and transfer (other than interstate transportation) in New York City (NYC). In response to a 1973 explosion during construction activities at a Staten Island LNG facility, the state enacted a moratorium on siting of new LNG facilities and intrastate transport of LNG under a 1978 statute. On April 1, 1999, the state lifted the moratorium for all locations except NYC, where it has been extended every 2 years. However, new facilities and transportation cannot occur in other areas of the state until new state regulations are developed and certified transportation routes are defined.

Recent pressure by industry has caused the state to move on the need for regulations to facilitate use of LNG as a transportation fuel. On September 26, 2013, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) proposed regulations that would permit siting, construction, and operation of LNG truck fueling stations and storage facilities in the state. DEC emphasized that recent interest from New York State businesses and utilities in LNG projects calls for new regulations conforming to the state Environmental Conservation Law. The proposed regulations would apply to LNG liquefaction and dispensing facilities and would not require permits for LNG-fueled vehicles or vessels. They would not affect the existing statutory moratorium that bans new LNG facilities in NYC. The proposed regulations specify permit requirements and application procedures, including:

- requirements for site inspections;

- fire department personnel training;

- closure of out-of-service LNG tanks;

- spill reporting;

- financial guarantee;

- and permit fees.

It is expected that the new regulations will allow the development of marine bunkering facilities in New York State other than NYC. Until the regulation related to NYC is also changed, the opportunities for LNG bunkering in the city ports are limited to:

- (1) interstate supply of LNG by truck to an NYC location;

- (2) vessel-to-vessel bunkering using a supply vessel engaged in interstate transport of LNG;

- or (3) bunkering at a fixed facility located in another state (e. g., the New Jersey portion of the Port of New York/New Jersey).

State, Provincial, Local, and Port Issues for Bunkering Facility Development

Early bunkering projects have been driven by forward-thinking vessel companies and LNG suppliers. This section first provides insight into LNG facility approval efforts in various ports and then outlines the consultation and coordination process that has been successful for LNG-related projects in the US and Canada.

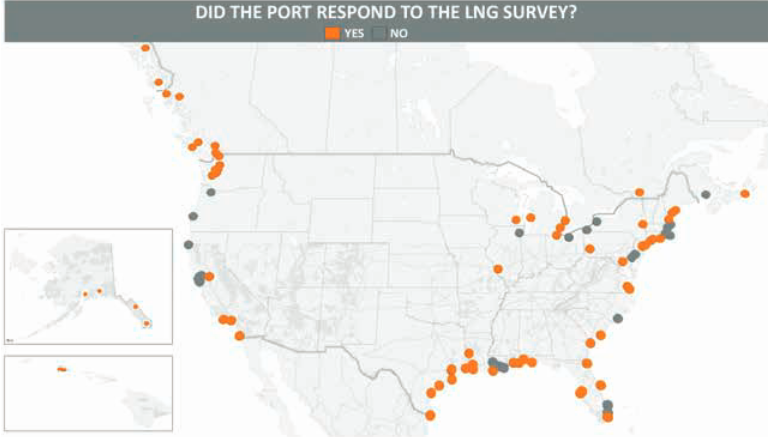

Port Survey. ABS contacted and visited ports in North America to collect details from stakeholders, Port Authorities, Harbor Safety Committees, regulators (including USCG) and other vested parties interested in LNG and LNG bunkering at their respective port. Questions from these visits and discussions centered on receptivity/plans for LNG development, state/local regulations, ongoing projects (exploratory/pre-production, current production and post-production phases), and local development processes for including LNG within their port.

Using World Port Source as a guide for varying sizes of ports, categorized as Very Small, Small, Medium, Large and Very Large, as well as interest in LNG and LNG bunkering based on media reports and other sources, ABS leveraged a tiered system based on HIGH, MODERATE and LOW interest in LNG and LNG bunkering in a particular port. These contacts and visits provided a «boots on the ground» perspective as to what is going on in North America based on stakeholder views, perspectives and, more broadly, what each particular region of the US and Canada feels and needs to consider when looking into LNG and LNG bunkering projects. In these stakeholder engagements it is important to note that these were opinions of those stakeholders and may not necessarily reflect federal, state, provincial and local regulations or public position. However, based on the Process Map & Organization of the LNG Bunkeringbunkering projects that are being pursued, port organizations are supportive of LNG bunkering projects when the companies that operate vessels in their port and/or potential LNG suppliers propose such projects. LNG availability is expected to be a potential competitive advantage for ports working to attract new shipping operations in the near future.

Stakeholder discussions addressed:

- Current LNG use in the port (if any).

- LNG bunkering projects under way.

- Interest in/study of/planning for future LNG bunkering activities.

- Existing or proposed state/local regulations that would apply to LNG bunkering operations.

- Agencies implementing LNG-specific regulations and/or issuing facility permits.

- Studies done regarding future LNG use.

- Active efforts by the port to make LNG fuel available to support future business plans.

Figure 1 shows the ports contacted and those where stakeholder discussions were conducted.

Figure 2 summarizes responses about the general acceptance of LNG in the region and provides the location of potential LNG sources and proposed/ongoing LNG bunkering projects. See below provides additional discussion of the port survey and stakeholder discussions.

In these discussions, the local representatives generally confirmed what ABS had learned from LNG bunkering project developers and what is conveyed in the port consultations. Port authorities are generally taking a wait-and-see approach, and projects in development have been driven by the developers themselves as opposed to port organizations. From a state/local regulatory standpoint, outside of the New York state moratorium on LNG facilities (see above), none of the representatives from the other states were aware of any state or local LNG-specific rules. The potential federal, state, and local regulatory agencies currently have some uncertainty as to which agencies will be responsible for permitting and authorizing facilities, but all see the USCG and the state and/or local fire marshal as playing key roles.

All of the representatives, including those from regulatory agencies, were supportive of potential LNG bunkering projects if developers propose projects for their port, and they clearly recognize the differences in the scale and regulatory authority between LNG bunkering facilities and LNG import/export terminals. In short, evidence the ABS team gathered suggests that developers should not be dissuaded from pursuing projects in maritime markets due to fear of regulatory impasses.

Table 1 provides a general list of potential regulatory agencies and organizations with whom a developer should consult and coordinate during a facility development process. The list will vary by location because of differences in state, provincial, county, municipal, and port/maritime organizations.

| Table 1. Organizations for Consultation and Coordination Efforts | |

|---|---|

| Organization | Comments and Areas for Discussion |

| Potential Regulators | |

| USCG/Transport Canada | ✔ Current USCG/Transport Canada HQ policies and regulatory status |

| COTP/Transport Canada Regional Authority or designees (for facility locations and for bunkering vessel transit areas) | ✔ USCG/Transport Canada safety, security, and environmental requirements |

| Headquarters (HQ) organizations (if recommended by sector/regional personnel) | ✔ Local requirements |

| ✔ Other local agencies and organizations to contact | |

| DOT PHMSA/National Energy Board | ✔ DOT/National Energy Board regulations (if any) that apply to a bunkering facility connected to a natural gas pipeline |

| ✔ Where the regulatory boundaries will occur | |

| ✔ Any hazardous materials transportation issues (when truck transportation of LNG is involved | |

| State/Provincial Pipeline Inspection Agency | Some states have been delegated selected federal regulatory authority for interstate pipelines (i. e., Arizona, Michigan, Ohio, Connecticut, Minnesota, Washington, Iowa, New York, West Virginia). Also, state pipeline inspection agencies are responsible for in-state pipelines |

| ✔ Applicable state/provincial requirements and regulatory procedures | |

| US Army Corps of Engineers (COE) | The COE has responsibilities in the area of waterfront facilities, wetlands protection, and other aspects of the shoreline that a bunkering facility may need to address |

| ✔ Regulatory procedures, including: – Information that must be submitted – Permits/approvals that are required | |

| State, Provincial and/or Local Fire Marshal Office | ✔ Codes and standards the fire marshal expects the facility will meet (e. g., NFPA 59A, NFPA 52, CSA Z276) should be discussed |

| ✔ Local fire codes may also be relevan | |

| State or Provincial Natural Gas Regulator | Some states have natural gas regulations that apply to «LNG facilities». However, those regulations are typically designed to apply to companies supplying natural gas to utilities and distributors in the state. Massachusetts is an example of a state with an LNG facilities regulation that would apply to bunkering facilities that store LNG |

| ✔ Relevance of state/provincial natural gas regulations (if any) to bunkering facilities | |

| EPA/Environment Canada | The EPA has a 2 006 document that describes its involvement in «LNG facilities;» however, that document only addresses facilities subject to FERC or MARAD review processes (i. e., import and export facilities, either onshore or at deepwater ports). Some standard EPA requirements will apply based on legislation such as: |

| ✔ Clean Air Act | |

| ✔ Clean Water Act | |

| ✔ Resource Conservation and Recovery Act | |

| ✔ Other requirements depending on the technology involved | |

| One reason to coordinate with EPA/Environment Canada is to determine whether they or a local agency has these responsibilities for the area in which the project is proposed | |

| State, Provincial, and Local Environmental Regulators (e. g., Division of Environmental Quality, Department of Ecology, State EPA) | Environmental regulations at the state, provincial, local level can vary greatly. Reaching out to the applicable organizations early is important |

| ✔ Applicable environmental agencies and regulations | |

| ✔ Extent of EPA/Environment Canada versus local permitting | |

| Local planning/zoning commission | ✔ Discussion of local planning/zoning requirements |

| Local Maritime Community | |

| Port Authority | Port authorities may have specific requirements regarding bunkering within the port |

| Marine Exchange | Marine exchanges can help identify issues and provide a conduit for communication to other maritime stakeholders (e. g., vessel and terminal companies that operate in the port area) |

| ✔ Experience with regulators | |

| ✔ Concerns from other users of the port | |

| Marine Pilot Associations | ✔ Types of port entries and exits that currently require pilot involvement |

| ✔ Input regarding appropriate locations/times for bunkering of vessels | |

| Other Local Organizations | |

| Local Fire Department | ✔ Concerns/requirements for facility access and fire response planning |

| ✔ Coordination of training regarding LNG hazards | |

| Emergency Medical Services Agency | ✔ Concerns/requirements for facility access and medical response planning |

| ✔ Coordination of training regarding LNG hazards | |

| State/Provincial/Local/Port Law Enforcement Agencies | Security assessments, plans, and coordination requirements |

As an example, Table 2 presents the state and local permitting agencies identified for the Long Beach LNG Import Project proposed for Long Beach, CA.

| Table 2. Example of LNG Terminal Coordination Efforts for One State (California) | |

|---|---|

| Agency | Permit/Approval |

| Project: Long Beach LNG Import Project (Long Beach, CA) | |

| State | |

| California Coastal Commission | Federal Coastal Zone Management Consistency Determination |

| California Department of Transportation | Encroachment and Crossing permits |

| California State Historic Preservation Office | Consultation |

| Native American Heritage Commission | Consultation Note: Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to consider the effects on historic properties of any project carried out by them or that receives federal financial assistance, permits, or approvals, and provide the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation an opportunity to comment on these projects prior to making a final decision.x |

| Regional Water Quality Control Board, Los Angeles Region | National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Storm Water Discharge Permit, Hydrostatic Testing, Water Quality Certification, Dredging Spoils (disposal) |

| Local | |

| City of Long Beach Engineering/Public Works | Encroachment Permit |

| City of Los Angeles Engineering/Public Works Department | Encroachment Permit |

| County of Los Angeles Health Hazardous Materials Division | Hazardous Materials Business Plan |

| Risk Management Plan | |

| Port of Long Beach | Harbor Development Permit |

| Port of Long Beach Development Services/Planning Department | Building Permit |

| Port of Los Angeles Engineering/Public Works Department | Encroachment Permit |

| South Coast Air Quality Management District | Permit to Construct/Permit to Operate |

Providing this information for LNG import/export terminals does not imply that bunkering facilities will have to meet the same requirements as those large, federally approved facilities. For example, coordination with historical preservation agencies and tribal organizations representing Native Americans is required for federally approved facilities as part of the environmental impact assessment process they undergo. Whether similar requirements (or recommendations) apply to smaller, bunkering facilities will depend on local regulations and conditions. By presenting all of the stakeholders, the tables provided here give a developer a starting point in identifying what coordination may be required.

Ports and Infrastructure

This section summarizes the findings of each region of the US and Canada. In the previous version of this study, ABS reviewed more than a dozen port regions in the United States and Canada in attempt to identify LNG bunkering interest, ongoing LNG bunkering projects, political climate as it related to potential LNG bunkering projects and public interest or concerns. In this updated revision of the study, ABS focused on similar LNG bunkering related issues and reached out to more than 100 federal, state and local regulators, port authorities, harbor safety committees, and industry representatives in the US and Canada. Of the 100 initial inquiries, ABS actually interviewed 73 respondents. The information in this database provides the necessary groundwork for initial research and port-specific considerations when developing an LNG bunkering project.

The United States

ABS engaged with stakeholders within the USCG, including two of the USCG Centers of Expertise that can be contacted for assistance with LNG related issues; the Liquefied Gas Carrier National Center of Expertise (LGCNCOE) and the Towing Vessel National Center of Expertise (TVNCOE). These two organizations and their subject matter experts are available to assist interested parties in navigating the LNG process. The LGCNCOE maintains trained experts on the liquefied gas shipping industry to serve as in-house consultants to the USCG and as participants in technical forums and decision-making collaborations, provide technical advice to both the industry and the USCG, and increase and maintain the USCG’s collective competency and capacity to professionally engage with the liquefied gas shipping industry. While the LGCNCOE is not an approval authority, it can support industry in navigation of applicable requirements and approval procedures, as well as interact with and support Sector Prevention staffs and USCG Program offices for projects involving liquefied gas carriers, liquefied gas facilities, and use of liquefied gases as a fuel or bunkering operation. The TVNCOE maintains trained experts in the towing vessel industry to serve as in-house consultants to the USCG and as participants in technical forums and decision-making collaborations, provide technical advice to both the industry and the USCG, and increase and maintain the USCG’s collective capacity, competence, and consistency to professionally engage with the towing vessel industry. While the TVNCOE is not an approval authority, it can support industry members in navigation of applicable requirements and approval procedures for towing vessels, as well as interact with and support Sector Prevention staffs and USCG Program offices for projects involving towing vessels.

The Pacific Coast, Alaska and Hawaii

The Pacific Coast of the US, including Alaska and Hawaii, is showing moderate interest in the use of LNG as a marine fuel. In particular, the Seattle/Tacoma region is where there is high interest in LNG. Representatives from ports that were contacted expressed interest in building an LNG bunkering infrastructure, but they highlighted a common dilemma that has stalled progress. Acknowledging that there are a couple of exceptions for those projects that are moving forward in North America, there is still the sense that vessel operators are waiting for LNG suppliers or bunkering operators to build the shore side or waterside infrastructure to ensure a reliable supply of LNG. Bunkering operators likewise are waiting for LNG suppliers and vessel operators to initiate development before making the financial commitments to build LNG bunkering vessels. The state and municipal governments are, in most areas, in favor of bringing LNG as a marine fuel to their ports, though there has been some in some areas. Port Authorities and local level governments play a critical role in the project approval process and in most ports; it is required to seek initial concept, interim and final approval for any LNG project and in most cases the primary approving authority will be at the state or local level. Most of the ports responding to the survey indicate that they have not been approached regarding LNG bunkering projects. The few that had been approached characterized the exchanges as preliminary.

In Alaska, Hawaii and Washington, the political climate is favorable to new LNG projects. Lower fuel costs, environmental advantages of a smaller carbon footprint and the potential availability of LNG are the primary driving factors for the high interest. All three states are currently in the initial research and planning phases of an LNG project for import/export, LNG as a fuel source for utility power generation, or LNG as a marine bunkering fuel.

Three notable projects in Washington are the Washington state ferries planned conversion of six of the Issaquah class ferries to LNG, Puget Sound Energy’s (PSE) planned multi-model peakshaving and distribution facility in Tacoma and TOTE planned conversion of its two Orca Class Roll-on/Roll-off (RO/RO) cargo ships with service between Washington and Alaska. The WSF ferry conversion project is moving forward slowly while still awaiting funding for the project. PSE plans to break ground on construction of their peakshaving facility in 2015 with plans to supply LNG to the local economy during peak energy needs, supply LNG for trucking, buses and other vehicles, as well as supply LNG as a marine fuel.

In Alaska, there is a long standing history of success with LNG. This has led to strong government and public support for the use of LNG as an energy source and proposed LNG projects. There is a proposed Trans-Alaska gas pipeline being considered from the North Slope to the tide water in Cook Inlet that would link up with a proposed facility in Nikiski. The Alaska Marine Highways is looking into the use of LNG as a fuel for the ferry Tustumena replacement. There are design considerations to be evaluated such as; fuel tank placement, tank design in accordance with USCG regulations and capacity to carry fuel for one week. These issues are being evaluated during the ships design phase and will determine if LNG will be used as the fuel source. Due to the vast geographic expanse of Alaska and the remote locations of many of the small towns and villages and potential complications with safe navigation due to cold and icy conditions, LNG bunkering operations are less viable particularly in the Northern waterways. The South Eastern ports could potentially see LNG bunkering operations in the future but this potential will be driven by supply and demand. The USCG Sectors that had been approached about potential LNG bunkering project characterized the exchanges as preliminary.

Hawaii’s interest in LNG centers on using LNG as a potential alternative power generation source. Hawaiian Electric Company, Inc. (HECO) is looking into the possible use of LNG as lower cost alternative for power generation and as a cleaner fuel source to comply with environmental standards. Jones Act requirements, finding suppliers willing to ship relatively small volumes and developing infrastructure to support LNG use are factors currently being addressed.

Hawaii Gas (HI Gas) is the Hawaiian Islands only franchised public gas utility. In 2014, HI Gas began shipping LNG in 40 foot specialized cryogenic tank containers transported out of Los Angeles via Matson, Inc. Ocean shipment. HI Gas uses this low volume LNG to supplement production of Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG) but expects LNG to replace SNG in the future which would require large LNG volumes. There is currently no LNG bunkering projects proposed in Hawaii. Jones Act restrictions and geographic location are significant challenges facing Hawaii and its availability to LNG sources. If LNG were to become available in Hawaii in large quantities, bunkering operations could become an option if demand required it. According to stakeholder interviews, LNG bunkering does not seem likely in the foreseeable future in Hawaii.

LNG project developers have shown interest in Oregon and California but the political climate, public acceptance and lack of LNG bunkering infrastructure or demand have forced potential projects to stall. As such there has been little movement beyond consultations. This finding is also supported by the observations from interviews with the USCG Sectors in California. Most contacted for this study indicated that they have not been approached regarding potential LNG bunkering operations. The few Sectors that had been approached about potential LNG bunkering projects characterized the exchanges as preliminary.

The Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast region has numerous sources of LNG, and a receptive political and social climate that make it ideal for early adoption of LNG as a marine fuel. Yet interviews with stakeholders in the region reveal that there is limited activity that LNG bunkering projects are moving forward at this time.

The one notable exception is Harvey Gulf International Marine, who will soon have in operation the first of its two ABS classed dual fueled LNG-powered OSVs. The first of these vessels has been bunkered and will soon be in operation at the Port Fourchon facility. These vessels will be among the first to be classed under the ABS Guide for Propulsion and Auxiliary Systems for Gas Fueled Ships. The vessels have received environmentally-friendly notations from ABS, including an ENVIRO+ notation which denotes vessels that adhere to enhanced environmental standards. In addition to providing LNG fueling for its own vessels, Harvey Gulf sees their facility as the first step to building an LNG supply infrastructure for other OSVs in the oil and gas industry. Harvey Gulf plans to make the facility capable of supporting over-the-road trucks that operate on LNG as well.

There have been some recent public announcements of potential LNG bunkering projects in the Gulf Coast region. In November 2014, Tenaska NG Fuels announced that they will construct a natural gas liquefaction and fueling facility along the New Orleans-Baton Rouge Mississippi River corridor with access to the Gulf of Mexico. In October 2014, LNG America announced they had reached an agreement with Buffalo Marine Service, Inc. to cooperate on the design of an LNG bunker fuel network for the US Gulf Coast region. There are potential markets for LNG bunkering services in the Gulf Coast region, such as towing vessels and OSVs. According to US Army COE’s report Waterborne Transportation Lines of the United States, Volume 1, 2012, there are approximately 3,500 towing vessels that operate on the Mississippi River and Gulf Intercostal Waterways. There are also approximately 1 600 OSVs operating in the US, of which the vast majority operates out of the Gulf Coast region. As a result of the increasing market, USCG Sector Mobile issued a Policy Letter, dated May 9, 2014, providing guidelines for the transfer of LNG as a marine fuel, largely drawing off of 33 CFR Parts 105, 127 and 156. The letter states that the recent need for a Policy Letter is a result of the COTP wanting to, «help owners, operators, and Coast Guard personnel understand the regulations that apply to specific types of LNG marine fuel transfer operations that are viable within the Mobile COTP Zone». In particular, the letter notes that waterfront facilities that handle LNG are regulated by 33 CFR 127 and that as a general policy for the Mobile COTP Zone, vessels transferring LNG fuel, to or from a fixed LNG facility will be regulated by this provision. As a result of this Policy Letter, in June of 2014 the COTP developed a Bunkering Checklist for USCG Sector Mobile using 33 CFR as its basis. However, there remain logistical and technical challenges with providing LNG to towing vessels and OSVs. Some of the challenges noted are unproven concepts and technology for midstream refueling, space restrictions for LNG fuel tanks in vessels, tight financial margins particularly for bulk agriculture commodities that do not support the return on investment, transient marine traffic patterns, and uncertainty about regulations or restrictions for LNG bunkering operations that may impede operational schedules.

The Atlantic Coast

The interest and activity associated with LNG bunkering on the Atlantic Coast can be roughly divided into three large geographic regions:

- North Atlantic;

- Middle Atlantic;

- and South Atlantic.

The North Atlantic Region includes the coastal states of:

- Maine;

- Massachusetts;

- New Jersey;

- New York;

- Pennsylvania;

- Connecticut and Rhode Island.

The Middle Atlantic Region is comprised of the coastal states of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. The South Atlantic Region is made up of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

The North Atlantic region can be characterized as having virtually no activity regarding LNG bunkering projects. Politically and socially LNG has not been generally accepted, even to potentially small scale bunkering operations. Most stakeholders expressed the opinion that LNG as a marine fuel will have to be proven elsewhere before it progresses in this region. The USCG Sectors in this region confirmed this sentiment. None of them have been approached by potential LNG bunkering projects for consultation. The one exception has been conversations between Staten Island Ferries and USCG Sector New York regarding the potential conversion of one of two Alice Austen Class ferries.

The activity and interest in LNG bunkering in the Middle Atlantic region can be characterized as a moderate level of interest but very limited activity. The public climate is rather neutral towards LNG bunkering operations. As long as the operations were located away from population densities or heavy marine traffic, LNG bunkering would probably not meet with much opposition. In some areas, DoD is a major port stakeholder. Consistent with the recommended approach for any port, consultation with DoD is advised for an LNG project. The most likely early adopters of LNG as a fuel in this region would be ferries, harbor tugs and coastal towing vessels on dedicated routes. Vessels that have dedicated routes of limited durations make it an ideal market for potential LNG bunkering operations because of their predictable schedules and short logistical lines. The United States Navy has a growing interest with a «wait and see» approach for LNG as a maritime fuel. The Navy’s interest in LNG is centered primarily on Secretary of the Navy, Ray Mabus, and his «Green the Fleet» initiative to find cleaner energy alternatives across all commands. Currently exploring bio-fuels, the Navy’s future interest in LNG could involve MSC vessels, but also as a conversion to electricity capability for all ships in the fleet. Although underway replenishment capabilities would be a concern, particularly for warships, the fact that LNG is being discussed within Department of Defense (DOD) circles demonstrates its future potential.

The South Atlantic region is the most promising East Coast region for the development of LNG bunkering, and both activity and interest in this area can be characterized as high. The political and social environment is accepting of LNG and actively seeking LNG bunkering infrastructure. The large ports of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida have long been engaged in a dynamic competition to attract and retain container and RO/RO cargoes. Some of the stakeholders expressed the sentiment that having a robust LNG bunkering infrastructure would provide a competitive advantage. The USCG Sectors in this region also indicated that there is active ongoing engagement from potential LNG bunkering projects.

By far the most advanced LNG bunkering project in the region is being jointly developed by WesPac Midstream, Pivotal LNG, and TOTE in the Port of Jacksonville. The first phase of the project is primarily focused on providing LNG to fuel TOTE’s two new dual-fuel Marlin-class containerships. In October of 2014, WesPac Midstream purchased 36 acres of industrial waterfront near the Jacksonville Port Authority’s Dames Point Marine Terminal. The plan is to have the facility operational in 2016. The facility will also supply other customers in Jacksonville and regional markets.

Though not directly related to LNG bunkering projects but indicative of the positive political and social climate toward LNG in the region, there are other projects related to the marine application of LNG that have been approved. Crowley Maritime was recently awarded two multi-year contracts to supply containerized LNG to major manufacturing facilities in Puerto Rico. The LNG will be transported in 10 000 gal, 40 foot intermodal containers to the Crowley’s Jacksonville, FL, terminal, where they will be loaded onto Crowley vessels for shipment to Puerto Rico. Additionally, in September of 2014, Pivotal LNG announced a long-term agreement to sell LNG to Crowley Maritime.

In January 2015, Florida East Coast Industries announced that it proposes to build a $ 250 million LNG facility near Titusville, which is 40 miles due east of Orlando, FL. Florida East Coast Industries states that it hopes to be operational by 2016. The facility will have a five million-gallon storage capacity and the capability to load to truck or rail. Florida East Coast Industries states that they plan to make their LNG available for trucking, maritime, electrical generation and space applications.

In-Land Rivers and Great Lakes

The Inland Rivers and Great Lakes regions can be characterized as having medium interest regarding LNG bunkering projects. Politically and socially there is no opposition to LNG and some of the utilities companies have shown interest in LNG as a potential energy source. Interviews revealed that there are numerous logistical and technical challenges with providing LNG to towing vessels. Some of the challenges highlighted were unproven concepts and technology for midstream refueling, space restrictions for LNG fuel tanks in vessels, tight financial margins that do not support the return on investment, and uncertainty about regulations or restrictions for LNG bunkering operations that may impede operational schedules. This sentiment was confirmed by the USCG. Most of the USCG Sectors in this region have not been approached by potential LNG bunkering project developers. The Towing Safety Advisory Committee (TSAC) organized an LNG working group to study LNG bunkering interest on the Western Rivers. A draft report (Recommendations for Mid-Stream Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) Refueling of Towing Vessels) was posted for distribution on the USCG Homeport web site on September 16, 2014 to allow further subcommittee review and provide public access.

The intent of the study was to identify gaps in current USCG policy and regulations of LNG mid-stream fueling operations, and to identify operational requirements, procedures, and parameters necessary to support consideration for allowing these types of refueling operations to be conducted safely. The final report will be published following official TSAC review and approval.

The Great Lakes region has expressed interest in LNG bunkering operations but there has been little discussions regarding development of LNG bunkering projects. Discussions with stakeholders identified key factors including the current state of the economy (depressed), age of the fleet in both the towing industry and the Lakers association, lack of LNG infrastructure and supply and the economic risks of retro-fitting the existing fleet or building new vessels. Most of the USCG Sectors in the region have not been approached regarding potential LNG bunkering operations. The Sectors or industry representatives that had been approached about potential LNG bunkering project characterized the exchanges as preliminary.

In regards to LNG and LNG bunkering options in the Great Lakes region of the US, the concept of LNG fueled ships has strong support, especially as Canada continues to progress in LNG export and LNG powered vessel operations. BLU LNG, which is making headway into its remote LNG refueling station operations in Central Canada, currently has two LNG bunkering permits under review for Duluth and South Lake Michigan. In anticipation of growing LNG fueled vessels operating in both US and Canadian waterways, industry stakeholders have identified three bunkering locations that could support Great Lakes traffic: Detroit, South Lake Michigan and Duluth.

Canada

LNG and LNG bunkering interest in Canada is positive due mostly in part to general Canadian public sentiment being receptive to LNG, as well as existing guidance and support from provinces and the Federal government. Provincial authorities and the Federal Canadian government are the lead points of contact and work together in regards to LNG projects, both existing and proposed. Currently, Canada has one existing import terminal at St. John in New Brunswick, Canaport LNG which is a facility run by Repsol/Irving. There is over a dozen other proposed LNG export terminals and one LNG bunkering opportunity being discussed as well. The Canadian Ministry of Transportation, Transport-Canada, oversees the 18 port authorities under its jurisdiction and through the Canadian Ministry of Natural Resources; the Canadian Government has been tracking existing, proposed and potential LNG import and export terminals around the country. The main regulatory guidance/standard for proposed LNG project is through CSA, particularly through CSA-Z27666, but Canadian LNG regulatory guidance is still in its development stages and the Canadian government is in the process of developing LNG bunkering specific regulations. Canadian stakeholders indicate that Canadian regulators are waiting on the international community to develop regulatory guidance, through the IMO and the IGF Code. Aside from lack of strong regulatory guidance, other challenges include funding and supply issues in regards to LNG and facility construction.

Concerns within the provinces, if any, is in regards to the impact on rights such as the right to fish, the right to hunt, the right to gather, and other personal rights of Canadian «First Nation» citizens. A helpful tool that is currently being utilized by Transport-Canada, and could serve as a best practice for industry and local authorities, is a voluntary TERMPOL review. TERMPOL reviews are done with specific guidance in mind, which may include polling local sentiments, but also includes as part of its submission:

- Transit and Site Planning;

- Cargo Transport Assessment;

- Berth Procedures Assessment and an overall Risk Assessment Study.

The details are filled out by project stakeholders through a TP-743 Guidance form that is available through Transport-Canada. According to Transport-Canada, there are 7 TERMPOL’s being performed for proposed LNG Facilities. These TERMPOL’s help identify gaps and review local «endorsements» with few regulatory impacts. However, in regards to mandatory reviews for an LNG project, there are two different Environmental Assessments: the Canadian Federal government performs one through the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) and; the Provincial authority does one through its environmental agency, for instance, the British Columbia Environmental Assessment Agency.

Aside from Transport-Canada and provincial authorities, including port authorities, other notable regulatory agencies that organizations interested in developing LNG and LNG bunkering projects should consider engaging include:

- the Canadian Department of Fisheries;

- CEAA;

the Canadian Department of Fisheries, CEAA, the Canadian Coast Guard and the Canadian Marine Pilots Association. In regards to approving of LNG fueled vessels themselves, which is influencing the LNG export terminal and LNG bunkering discussions, the class societies in Canada would be the lead, in coordination with Transport-Canada.

Canada’s Marine Liquefied Natural Gas Supply Chain Project is a joint industry project focused on the use of LNG. The project involves:

- marine classification societies;

- technology and services providers;

- standards development groups;

- federal and provincial governments;

- and natural gas producers and suppliers.

Stringent emissions regulations coming into force in 2015-2016 mean that vessel owners operating within 200 miles of the East and West Coast of Canada will need to use lower sulphur distillate fuel, install exhaust after treatment technologies, or switch to LNG in order to comply. The project focus is on technology readiness, training, safe operations and regulatory requirements, and environmental and economic benefits from a Canadian point of view. The project approach is to be conducted in 3 phases:

- Phase 1 – West Coast (Nov 2012 – Apr 2014);

- Phase 2 – Great Lakes and St. Lawrence;

- and Phase 3 – East Coast.

Phase 2 and 3 final reports are expected September 2015. The Phase 1 report, Liquefied Natural Gas: A Marine Fuel for Canada’s West Coast, summarizes project results related to identifying and addressing barriers to the establishment of a LNG marine fuel supply chain on Canada’s West Coast. The project contributed to the development of a thorough understanding of key issues and how to design approaches that will encourage the use of LNG as a marine fuel in Canada.

The Pacific Coast

Many of the current LNG and LNG bunkering talks in Canada are occurring on the Pacific Coast (i. e., British Columbia [BC]). Numerous proposed or potential export terminals are being discussed and developed by stakeholders as well as monitored by Transport-Canada in many regions of the province (see Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Table Proposed/Potential Canadian LNG Export Terminals”). Most of these LNG projects are targeting large scale exportation.

Currently the WesPac Midstream – Vancouver, LLC (WPMV) project, which is a subsidiary of WesPac, is the only project that is proposing LNG bunkering operations. The terminal would be located on Tillbury Island, which is located south of Vancouver, BC, on the Fraser River. There is an existing LNG storage facility on the island owned by Fortis BC Energy, Inc., called the Tillbury LNG Plant. FortisBC currently uses this facility to provide gas supplies during periods of peak demand. However, the facility does not have a marine terminal. WPMV is planning a new marine terminal adjacent to the Tilbury LNG Plant to accommodate export of LNG by barges or ships. The Tillbury LNG Plant, which currently has only one LNG storage tank, will be expanded to meet the increased demand.

Despite only one of these projects explicitly showing interest in pursuing LNG bunkering, all of these proposed or potential terminals could have LNG bunkering in their future and have expressed interest. This is especially true as a result of many BC coastal ferries beginning to convert from diesel to LNG, thus having the potential need for future LNG bunkering terminals. There are two companies in BC currently building LNG fueled vessels, British Columbia Ferries and Seaspan Ferries Corporation. In particular, British Columbia Ferries is not only retrofitting its fleet for dual LNG and diesel oil, but will be the first domestic fleet to also be building vessels that will solely run on LNG. Both of these companies have structured phases of LNG conversion and implementation to occur between January 2015 and September 2015.

The Atlantic Coast

Although not as many as the Pacific Coast, there are LNG projects on the Atlantic Coast, primarily in Nova Scotia. These LNG projects, all being monitored by Transport-Canada, include:

- proposed and potential LNG facilities at Guysborough;

- Nova Scotia;

- including Goldboro LNG and Melford LNG (see Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Table Proposed/Potential Canadian LNG Export Terminals”).

proposed and potential LNG facilities at Guysborough, Nova Scotia, including Goldboro LNG and Melford LNG (see Table 21). A challenge with these East Coast projects is the marine supply chain and getting the gas/LNG to those ports and regions of the country. In particular, the Bear Head LNG project would be looking for a supply from the Scotian shelf, Western Canada and shale gas from the US The Bear Head LNG has had discussions of its potential for LNG bunkering.

In Nova Scotia, public sentiment is favorable to LNG. Local authorities in Nova Scotia, when presented with an LNG project or proposal, poll its people to get their views or concerns. Working with industry proposing the project (such as Pieridae Energy Canada, H-Energy and Liquefied Natural Gas Limited representing the big three LNG projects), provincial authorities build consensus in advance and hold discussions on LNG planning with the local community way before a project gets underway, thus increasing its favorability with the public. The LNG facility regulatory process (typically taking 18 months and facilitated by Transport-Canada) includes the results of these public polls for all Project Study reports submitted for a public hearing before a panel of Canadian stakeholders/regulators. As a result of this advanced planning, local municipalities have already performed «pre-zoning» assessments of the coastline in their county for LNG use. Due to its unique location, the Halifax municipality requires a Coastal Pre-Zoning Assessment to be conducted before any proposed project gets off the ground.

Central Waterways and Great Lakes

Although there are a few notable projects and developments in the region with LNG, much like the East Coast, one of the main challenges is the supply chain of getting gas/LNG. In addition, one of the LNG projects being discussed in the region, which has LNG bunkering potential, recently announced a pause in further project development. In particular, the Great Lakes Corridor project being developed by Royal Dutch Shell and its liquefaction units in Sarnia, Ontario has been temporarily put on hold. The proposed terminal on the St. Clair River near Sarnia, Ontario and the shores of Lake Huron would have allowed Shell to supply LNG fuel to marine, rail and truck customers on both sides of the border along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway. Royal Dutch Shell hoped to pump natural gas into Great Lakes freighters, as it was seeking new ways to lift demand for the fuel. LNG fuel was to be provided to marine traffic, as well as trucks and trains through Sarnia, Ontario since it is an important refueling hub on the Great Lakes, where some 65 US flagged and 80 Canadian flagged ships regularly make port calls. Most of the US vessels are too big to move through the St. Lawrence Seaway, meaning they are essentially a captive fleet on the lakes, which appeared as an ideal place for Shell to offer a new type of fuel as LNG. The St. Lawrence Seaway, has faced obstacles from the beginning such as lack of rules and regulations, as well as the need for detailed permits and standards. The need was identified as an Ohio based company, Interlake Steamship, was developing LNG fueled ships that they were converting fuel capability, which the Sarnia facility would have served. Royal Dutch Shell’s announcement in Spring 2014 of the pausing of development of the Great Lakes Corridor project was described as a move to allow the company to review broader LNG-for-transport opportunities in North America and to ensure a more flexible and competitive portfolio. It is unclear whether this is just a pause in development, or leading towards a complete cancellation.

According to stakeholder input, in regards to Quebec, aside from the early stages for the GAZ Metro LNG project which is also supplying energy to remote areas of the province, there are no other LNG projects being proposed or discussed in this region. However, interest can be categorized as HIGH in the region, with strong public support, as GAZ Metro has been aggressively pursuing two LNG projects, one land based and one maritime. The land based project is called the Blue Highway Project (BLU LNG Project), overseen by Transport-Canada through their risk assessments, which involves a partnership with the largest trucking fleet in Canada, as well as the company BLU LNG, to provide gas fueling stations in remote areas of Quebec, as well as between Quebec and Ontario. The maritime project is based on an agreement between GAZ Metro and a Quebec ferry company called Société des Traversiers du Québec (STQ), which is currently building two LNG fueled ships. As a result, and possibly in anticipation of these LNG ship projects, GAZ Metro’s actual LNG facility is located at Port of Montreal. Stakeholder’s discussions with ABS have even gone so far as to state that Port of Montreal is very serious in exploring the option of LNG bunkering and is in discussions with potential industry clients, revealing that early conceptual phases are being explored (possibly 18-24 months out).

With the LNG market being so strong in Quebec, local stakeholders have turned and followed trends coming out of Europe for guidance. In fact, stakeholders in Quebec also have a Memorandum of Understanding with Antwerp, Belgium regarding LNG and energy best practices. In addition to STQ, European companies are also developing LNG fueled vessels that would operate within the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway in Quebec. Hoegh Shipbuilding Company, based out of Norway, is developing a floating LNG platform project for maritime refueling within Quebec as well as a Belgium company, Anglo Belgian Corporation Container lines, that is making dual-retro-fitted tanks, both diesel and LNG, for their container ships. Finally, an Italian company, Fincantierri, is building a dual-fueled LNG ferry that is scheduled for delivery and cross the St. Lawrence Seaway in mid-2015, which will be the first LNG ferry in Canada. These dual-fueled vessels switch to diesel when doing their landing approach, however when they are underway, they will switch to LNG.

Due to the high demand, Port of Montreal as well as other Quebec and Central Canada stakeholders comprise a group, organized by the Canadian Natural Gas Vehicle Alliance, currently working on developing a study and report on LNG in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway. In talking with Central and Eastern Canadian stakeholders, it was interesting that while LNG and LNG bunkering were so heavily considered, in regards to the US Great Lakes stakeholders, there was little interest expressed.

Consultation and Coordination Process for Bunkering Facility Development

The consultation and coordination process involved in developing a successful bunkering facility can vary based on the developer’s experience in the local area where the bunkering facility is proposed. In this discussion, the «development process» is considered a coordinated effort, including any of the following project participants that exist at the time:

- Project sponsor/organization.

- Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) firm(s).

- Law firms involved in local or federal (if any) licensing efforts.

- Environmental compliance and services consultant.

- Safety and security compliance consultant.

- Other regulatory compliance consultants.

- Media/communications consultants.

In some cases, the project organization will have one or more people on staff that can provide some of the expertise listed above; however, the list does not imply that a contract firm has to be hired for each of the specialties listed. The specific participants supporting the project will depend on the scope of the project and the experience of the people on the project staff and its major contractors (e. g., EPC firm, lawyers, and environmental consultant).

Communication with affected parties is always an essential element in project management activities, but for LNG activities, it is even more critical. When a company is considering development of an LNG bunkering facility or using LNG as a fuel for its fleet of vessels, it has to be aware of, and deal with, public and some regulatory perceptions of LNG as higher risk than other fuels and other cargoes (even other liquefied gases). This calls for communication efforts beyond those for other types of project developments.

This need has been clearly demonstrated in ABS experience supporting LNG facility development projects and USCG safety and security analyses in all regions of the US and Canada. Those types of efforts have often required public meetings, workshops, and meetings with representatives from individual agencies and groups of agencies to explain the nature of LNG, its properties, hazards, benefits, and how the project is designed to provide safe, reliable, and secure handling of LNG in the city, county, and state involved. Often, these communication activities required efforts that exceeded the level of public interaction required to obtain a specific federal agency approval or license. Because bunkering projects are smaller facilities, involving smaller LNG cargo vessels (if at all), and much lower inventories of LNG, the need for strong communication and the issue of public perception may be somewhat less of an issue, but companies proposing bunkering activities need to be prepared to address such issues throughout the development process.

The conclusion that early and continuous communication is a key element to LNG bunkering project success was re-emphasized at the second annual LNG as Fuel conference held in Seattle on January 27, 2015. The conference was attended by more than 200 representatives from every interest group in the LNG community. One of the strongest messages re-emphasized by each of the presenters related to the need for companies to communicate their project intentions early and often. This communications theme was echoed by conference attendees from:

- Federal regulators from the USCG in Washington, DC.

- USCG COTP in Seattle.

- USCG COTP MSU Houma, LA.

- USCG Liquefied Gas Carrier National Center of Expertise.

- Industry representatives from PSE, Washington State Ferries, Gas Technology Institute, GTT North America, Wärtsilä North America, ABS, DNV and Lloyd’s Registry.

PSE, WSF and other industry representatives in the development phases of various LNG projects continue to emphasize and acknowledge that communicating their intentions and seeking feedback from any and all regulatory, safety, environmental, tribal, or land owner entity are critical throughout the process.

Every region or port is different and the agencies and stakeholders in each state and port will vary. Communicating with the local USCG COTP regarding the intention to develop an LNG bunkering project is a key starting point. The listing includes:

- environmental regulators;

- natural gas/pipeline regulators;

- fire marshals;

- port authorities;

- pilot associations;

- and marine exchanges.

Communications efforts need to start with the discussions described in the previous section on coordination and consulting; however, that section largely focused on understanding requirements for getting a facility approved. This section is more concerned with getting a facility «accepted» which, depending on the locality, can have great influence on whether or not the facility will be approved.

Issues that need to be addressed in communications efforts regarding the project may include:

- Impacts on the community, including:

- Disruption during construction.

- Pollution (air, water, noise, light).

- Effects on fisheries.

- Maritime restrictions (if any) due to safety/security zones.

- Risks to the community and users of the waterways:

- Potential for LNG accidents.

- Increased vessel traffic.

- Increased vehicle traffic.

- Benefits to the community:

- Jobs (short term and long term).

- Potentially attractive pay scales for facility jobs.

- Taxes the project will pay to the local municipality and state.

- Reduced pollution from ships that use natural gas fuel.

This list will vary based on the nature of the community and to what portion of the public the communication effort is addressed. A few important concepts for communications efforts include:

Do Not Wait Until Controversial Issues Are Raised. When people know of the project, have met people involved in the project, and understand at least some information regarding the project plans, they are less likely to jump to unsupported conclusions. Good prior communication also gives them a chance to reach out to the developer representatives they have met to say, «I heard this. Is it true?»

Be Inclusive. Try to reach out to as many different organizations and segments of the population as practical.

Accept People’s Concerns as Valid. If people have concerns, do not dismiss them because they are not a concern you deem viable. Treat their concerns as valid and provide explanations to their concerns, explaining what the situation really is.

Good communications cannot guarantee a successful project, but effective communication has contributed to much wider acceptance and support for many of the LNG projects that have succeeded. Table 3 lists some of the kinds of communications efforts and organizations with whom a developer may want to communicate.

| Table 3. Opportunities for Effective Communications Efforts | |

|---|---|

| Organizations/Locations | Considerations |

| Municipal organizations – city and county boards | This is a primary place to stress benefits to the community. |

| School staff and students | Providing educational sessions for schools and providing literature for students to take home to parents can reach a significant fraction of a community |

| Police and fire departments | These organizations are trusted by their communities and their understanding of your project and involvement when appropriate carries a lot of weight with members of the public. |

| Public meetings sponsored by the project | Public meetings by the project may be required and can play an important role, but unless there is a large controversial issue, attendance tends to be light. Specific efforts to reach out to nearby property owners can be valuable. |

| Public meetings or areas of congregation for other reasons (i. e., not sponsored by the project) | Going to where people are for other reasons and making presentations or staffing a booth/display can often reach many more people than sponsored public meetings. Example of meetings sponsored by others include Chamber of Commerce, port authority, service clubs, economic development agency, marine exchange, etc. |

| Waterways user organizations | These can include fishing associations, boat/yacht clubs, marinas, etc. |

Conclusion

This study has been widely recognized by both industry and regulators as an information resource to guide users through many of the complex and interconnected requirements for bunkering projects. Therefore, the bulk of the information in the original report was retained in this revision for reference; however, additional information is also included that should be useful to interested LNG and LNG bunkering stakeholders.

Read also: Security Zones in LNG Bunkering: A Guide to Meaningful Protection

Opportunities for LNG projects in North America have grown since the first publishing of this study. The port visits and discussions revealed not only progress with previously identified LNG and LNG bunkering projects, but also found preliminary stages of project exploration by ports and port authorities within the US and Canada. Nevertheless, there remains some level of a «wait and see» attitude in some regions. Also of note is the growing interest by the United States Navy in LNG as a maritime fuel. The Navy’s interest in LNG is centered primarily on the Navy’s «Green the Fleet» initiative to find cleaner energy alternatives across all commands. The Navy’s position is also one of «wait and see».

The overall use of LNG as fuel for ships, other than those carrying LNG as cargo, is still a relatively new concept in North America. The US’s regulations, including current USCG policy for vessels receiving LNG for use as fuel, as well as Canadian regulations, continue to be in the developmental stages to appropriately address the options for marine fuel. Existing The ABS and USCG Additional Rules and GuidesUSCG regulations address the design, equipment, operations, and training of personnel on vessels that carry LNG as cargo in bulk and address fueling systems for boil-off gas used on LNG carriers. However, engagement with stakeholders indicates some hesitancy to move forward on projects until Federal Regulations are in place. In addition, the timing of this report coinciding with the significant drop in crude oil prices has lessened the economic advantages of LNG.

Regardless of the hesitancy in some cases, several companies have initiated and are well under way in their development of gas-fueled vessels and the corresponding infrastructure for LNG bunkering. Planning and execution of these projects involved a number of key decisions and resolution of regulatory, commercial and technical issues. The lessons learned from North America’s first adopters of gas-fueled vessels provide valuable insight for future project developers who are considering making an investment in LNG as an alternative marine fuel.

One of the common threads among North America’s early adopters is having gained the awareness that making the switch to LNG requires patience and persistence navigating an uncharted course. When making the decision to build or convert vessels powered by gas, shipowners and operators must consider a number of regulatory factors and address technical challenges associated with applying new technology to their fleets for the first time. The process to develop the first wave of gas-fueled initiatives in North America has required close collaboration, open communication, and shared best practices among classification societies, regulatory bodies such as the USCG and port authorities, vessel designers, and shipyards to establish a baseline for these next-generation vessels. LNG fueled marine vessels and LNG bunkering will continue to be a part of discussions on energy efficiency and environmental stewardship in the maritime industry.