LNG bunkering guidelines are essential for ensuring safe and efficient operations in the maritime industry. These guidelines provide a framework for gas-fueled vessel operators, covering everything from regulatory compliance to operational training requirements.

- Introduction

- What’s New

- LNG Drivers

- Regulatory Summary

- LNG Bunkering Options

- Lessons Learned from Early Adopters

- Decision to use LNG

- Partner Selection & Communication

- LNG Supply Availability

- Engaging with Regulators and Stakeholders

- Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators

- Ship Arrangements and System Design

- Operational and Training Requirements for Personnel

- Basic Training.

- Advanced Training

- United States

- Canada. Marine Personnel Requirements

- Guidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators

- International

- United States

- Canada

- Guidelines for Bunkering Facility Operators

- United States

- Canada

By following these best practices, stakeholders can enhance safety, streamline communication with regulators, and optimize LNG supply availability. As the demand for cleaner marine fuels grows, adhering to LNG bunkering guidelines will be crucial for the successful transition to sustainable shipping practices.

Introduction

Since this report was initially issued in March 2014, significant progress has been made in North America with the use of LNG as a fuel for marine vessels. Of particular note, is the first LNG bunkering and gas-fueled vessel operation in North America. Harvey Gulf International Marine, LLC (HGIM) has conducted the first gas fuel bunkering procedure of their newest Offshore Support Vessel (OSV), HARVEY ENERGY.

HARVEY ENERGY, constructed by Gulf Coast Shipyard Group, is a Dual Fuel Diesel OSV and the first gas fueled vessel to be constructed in North America. It is United States (US) flagged, and classed by ABS. The vessel is powered by three Wärtsilä 6L34DF dual fuel gensets providing 7,5 megawatts of power that are supplied fuel via Wärtsilä’s LNGPac system.

The bunkering event shown in Figure 1 occurred on February 6, 2015, at Martin Energy Services facility in Pascagoula, Mississippi and was supported by HARVEY ENERGY’s crew, Wärtsilä, Martin Energy, Gulf Coast Shipyard Group, Shell, ABS and the United States Coast Guard (USCG).

The bunker transfer included a truck to vessel transfer of Liquefied Nitrogen, used to cool the LNG fuel tank and condition the Type C tank and LNG. LNG was transferred from truck to vessel utilizing pressure differential. Three LNG delivery trucks provided approximately 28 700 gallons of LNG. The duration of the bunkering operation was approximately six hours. After LNG was bunkered, the engines were tuned with gas and have since conducted successful gas fuel trials.

The HARVEY ENERGY LNG bunkering debut has advanced the maritime industry in North America. Gas is now the new marine fuel in the US and has joined the historic vessel power transitions of sail to coal then coal to oil and now oil to gas.

HGIM is completing the final stages to operate the first LNG LNG Bunkering Guide – What It Is and How to Use Itmarine bunkering facility in Port Fourchon, Louisiana. Future gas bunkering evolutions for the HARVEY ENERGY will be conducted at the Port Fourchon facility.

What’s New

This second edition of Bunkering of Liquefied Natural Gas-fueled Marine Vessels in North America was developed to meet the growing needs of industry and to provide guidance and clarification on areas of interest based on feedback received on the first edition. Feedback on the initial version indicates that collectively, people using the report have referenced or used information from the entire report. Accordingly, we are, for the most part, retaining the original structure of the report to maintain familiarity and ease of use and have added and updated material in the appropriate sections. Significant enhancements have been provided, primarily in the areas of:

1 Lessons Learned from First Adopters of LNG-fueled vessels – Insights gained from the first adopters of LNG fueled vessels and bunkering projects help guide future users through the challenges and solutions achieved by existing projects. Several projects in North America are well underway, and in some cases completed, and provide valuable information to complete the value chain of LNG supply, port infrastructure and end user. This information is detailed below.

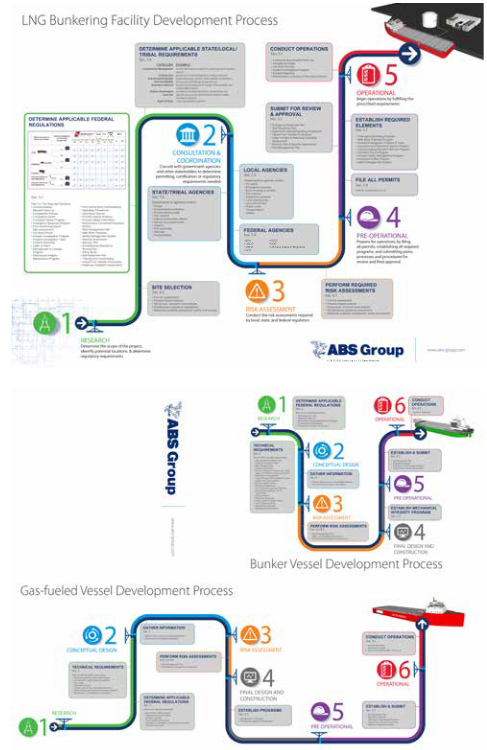

2 Project Guide – This provides a «road map» guide of the regulatory, stakeholder and technical issues associated with developing an LNG bunkering project. The included poster size info graphic provides a comprehensive guide for working through the various issues for a project. The graphic provides input for LNG bunkering facilities, gas-fueled vessels and LNG bunkering vessels.

3 Port Directory and Survey – ABS contacted and visited ports in North America to collect details from stakeholders, Port Authorities, Harbor Safety Committees, regulators (including USCG) and other vested parties interested in LNG and LNG bunkering at their respective port. Questions from these visits and discussions centered on receptivity/plans for LNG development, state/local regulations, ongoing projects (exploratory/pre-production, current production and post-production phases), and local development processes for including LNG within their port.

Stakeholder discussions addressed:

- Current LNG use in the port (if any).

- LNG bunkering projects under way.

- Interest in/study of/planning for future LNG bunkering activities.

- Existing or proposed state/local regulations that would apply to LNG bunkering operations.

- Agencies implementing LNG-specific regulations and/or issuing facility permits.

- Studies done regarding future LNG use.

- Active efforts by the port to make LNG fuel available to support future business plans.

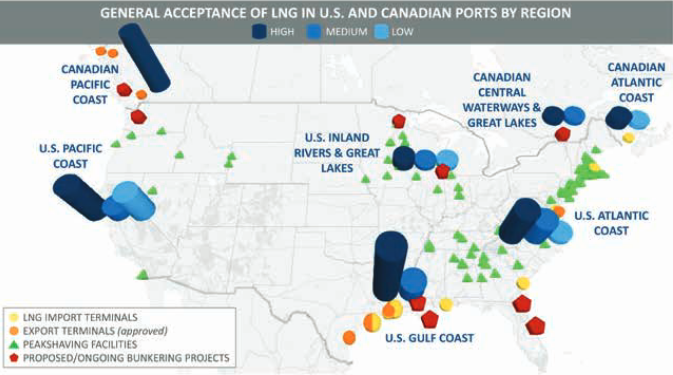

Figure 2 summarizes responses about the general acceptance of LNG in the region and provides the location of potential LNG sources and proposed/ongoing LNG bunkering projects. This information is detailed in Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Sources of LNG and Project Implementation to Make LNG Available for Use as a Marine Fuel” with Section Key Considerations for Successful Bunkering Facility Development“Ports and Infrastructure” providing discussion of the port survey and stakeholder discussions.

ABS also developed a comprehensive listing of North American ports providing key contact information and insights into current LNG activity and interest at each port. The information in this database provides the necessary groundwork for initial research into developing an LNG bunkering project. Insights gained from our direct experience assisting clients on bunkering projects guided the development of this resource listing.

Other updates – “How to Use This Study” provides additional clarification on how to use this study, as well as further guidance on new material provided in this update.

LNG Drivers

Due to increasingly stricter environmental regulations controlling air pollution from ships implemented through International Maritime Organization (IMO) Annex VI and other local air quality controls, together with the potential for favorable price conditions, the use of LNG as a fuel, instead of conventional residual or distillate marine fuels, is expected to become more widely adopted in the future. In anticipation of this trend, the marine industry is looking for ways to provide flexibility and capability in vessel designs to enable a future conversion to an alternative fuel, such as LNG.

Existing USCG regulations address the design, equipment, operations, and training of personnel on vessels that carry LNG as cargo in bulk and address fueling systems for boil-off gas used on LNG carriers. The use of LNG as fuel for ships other than those carrying LNG as cargo is a elatively new concept in North America. USCG policy for vessels receiving LNG for use as fuel are in development to address this option for marine fuel. USCG policy for LNG fuel transfer operations and for waterfront facilities conducting LNG fuel transfer operations are in CG-OES Policy Letters 01-152 and 02-153.

The ABS Guide for LNG Fuel Ready Vessels provides guidance to shipowners and shipbuilders indicating the extent to which a ship design has been prepared or «ready» for using LNG as a fuel. ABS is providing further guidance to assist LNG stakeholders by developing this study, Bunkering of Liquefied natural Gas-fueled marine Vessels in North America. ABS developed the first edition in 2014 to assist LNG stakeholders in implementing the existing and planned regulatory framework for:

- LNG bunkering and to help owners and operators of gas-fueled vessels;

- LNG bunkering vessels;

- and waterfront bunkering facilities by providing information and recommendations to address North American (US and Canada) federal regulations;

- state;

- provincial and port requirements;

- international codes;

- and standards.

The study has been widely recognized by both industry and regulators as an information resource to guide users through many of the complex and interconnected requirements for bunkering projects. Therefore, the bulk of the information in the original report has been retained in this revision for reference.

The effect of increasingly stricter air emissions legislation implemented through IMO Annex VI and other local air quality controls, together with favorable financial conditions for the use of natural gas as a bunker fuel is increasing the number of marine vessel owners that are considering the use of LNG as a fuel. Existing USCG regulations address the design, equipment, operations, and training of personnel on vessels that carry LNG as cargo in bulk and address fueling systems for boil-off gas used on LNG carriers. The use of LNG as fuel for ships other than those carrying LNG as cargo is a relatively new concept in North America. As stated previously, US and Canada regulations and USCG policy for vessels receiving LNG for use as fuel are in development to address this option for marine fuel. USCG policy for LNG fuel transfer operations and for waterfront facilities conducting LNG fuel transfer operations are in CG-OES Policy Letters 01-15 and 02-15.

This study was developed to assist LNG stakeholders in implementing the existing and planned regulatory framework for LNG bunkering. This study helps owners and operators of gas-fueled vessels, LNG bunkering vessels, and waterfront bunkering facilities by providing information and recommendations to address North American (US and Canada) federal regulations, state, provincial and port requirements, international codes, and standards.

LNG has different hazards than traditional fuel oil; therefore, operators must clearly understand the risks involved with LNG bunkering. An assessment of various bunkering operations and the associated hazards and risks is provided. Templates are provided for stakeholders to use in conducting appropriate Hazard Identification (HAZID) and analysis.

Details on LNG production in the US and Canada and LNG sources in various geographic regions provide an overview of the current North American infrastructure to support LNG bunkering operations. Local regulations are widely varied in maturity and content. To assist stakeholders in planning and execution of LNG bunkering projects, this study provides a structured process for implementing an LNG project with regard to seeking compliance with local regulations.

Decisions to convert to LNG involve consideration of factors primarily involving:

- Compliance with emissions regulations.

- Economic and cost drivers, including fuel costs, repowering and new builds, availability, and cost of LNG.

- Commitment to environmental stewardship.

Once these factors support the business case for converting to gas- or dual-fueled vessels, then the issues of bunkering infrastructure and reliable supply of LNG come into play.

Emissions Regulations

The IMO has adopted emission standards through Annex VI of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). The emission regulations in Annex VI include, among other requirements, a tiered compliance system introducing increasingly stricter limits on emissions of sulfur oxide (SOx), nitrogen oxide (NOx), and particulate matter (PM). In addition to global requirements, designated areas called Emission Control Areas (ECAs) are subjected to more stringent requirements for the same emissions. Two separate ECAs are currently enforced in the North American region: the North American ECA and the US Caribbean Sea ECA. In addition, two regional regulations limit SOx emissions from ships: California Air Resources Board and European Union Sulphur Directive.

NOx tier II requirements are currently in effect for applicable marine engines, and in ECAs areas, more stringent tier III requirements will be applied to marine diesel engines installed on ships constructed on or after January 1, 2016. Tier III requirements will not apply to marine diesel engines installed on ships constructed prior to January 1, 2021 of less than 500 gross tonnage (gt), of less than 24 meters (m) in length which have been designed and will be used for recreational purposes.

The tiered approach for sulfur means that the existing global maximum sulfur content of 3,5 % mass/mass (m/m) (outside an ECAs) will be reduced to 0,5 % m/m, in 2020. A Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) correspondence group was created to determine the availability of compliant fuel oil and publish a report of its findings by 2018. If the group determines the availability of compliant fuel oil is too limited, then this requirement could be postponed to January 1, 2025. A progress report on the group’s research is expected in 2015. In designated ECA areas, the sulfur fuel requirement has been reduced to 0,1 % effective January 1, 2015.

Complying with the international and US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations requires switching either to a distilled fuel, such as Marine Diesel Oil (MDO) or Marine Gas Oil (MGO), using another alternative fuel such as natural gas, or installing an exhaust gas scrubber system.

Critical among these regulations are the measures to reduce SOx emissions inherent with the relatively high sulfur content of marine fuels. Ship designers, owners and operators have three general routes to achieve SOx regulatory compliance:

1 Use low sulfur residual or distillate marine fuels in existing machinery. Marine fuel that meets the sulfur content requirements can be produced through additional distillation processing. Currently, low-sulfur MDO and MGO fuels are nearly double the cost of the Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO). Switching a ship from HFO to MDO/MGO fuel could result in a significant increase in overall vessel operating costs. In addition, these costs are expected to increase over time as demand for low sulfur fuel increases.

2 Convert or install new machinery to operate on an inherently low sulfur alternative fuel, such as LNG. The sulfur specification of LNG in numerous Sale and Purchase Agreements translates to about 0,004 % m/m, which is well below the 0,1 % limit in ECAs.

3 Install an exhaust gas cleaning after-treatment system (scrubber). The third emissions compliance option is to use a scrubber installed in the exhaust system that treats the exhaust gas with a variety of substances, including seawater, chemically treated freshwater, or dry substances, to remove most of the SOx from the exhaust and reduce PM. After scrubbing, the cleaned exhaust is emitted into the atmosphere. All scrubber technologies create a waste stream containing the substance used for the cleaning process, plus the SOx and PM removed from the exhaust.

While scrubbers offer the potential for lower operating costs through the use of cheaper high sulfur fuels, purchase, installation, and operational costs associated with scrubbers would also need to be considered. These costs should be assessed against the alternatives of operating a ship on low sulfur distillate fuel or an alternative low sulfur fuel, such as LNG. Fuel switching, meaning using higher sulfur fuel where permitted and lower sulfur fuel where mandated, has its own complications and risks, but should also be considered as part of the evaluation of possible solutions to the emissions regulations. Refer to the ABS Fuel Switching Advisory Notice for more information on the issues related to fuel switching.

Economic Factors

Natural gas is increasingly becoming a global issue and less the regional market it has been. Two examples include the 2014 announcement of a deal between Russia and China for pipeline gas previously destined for Europe, and the North American push to export LNG globally. Seemingly overnight, the US has become a swing oil producer, responding swiftly to market selloffs but likely to respond swiftly when demand/supply are rebalanced and prices recover. Assuming a trend toward increased global LNG trade, North America may become a global LNG supplier, as well. Operators considering the option of installing new machinery (or converting existing machinery where possible) designed to operate on an inherently low sulfur alternative fuel are seeing the LNG economic factors move in a favorable direction.

North America shale gas accounts for a significant portion of US natural gas production. Gross withdrawals from shale gas wells increased from 5 Billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in 2007 to 33 Bcf/d in 2013, representing 40 % of total natural gas production, and surpassing production from non-shale natural gas wells. Up from near zero in 2000, shale gas is predicted to account for about half of US gas output by 2040. A significant effect of the fracking revolution has been in LNG. In 2010, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) released estimates putting US natural gas reserves at their highest level in four decades, and in 2012 the US became the number one gas producer in the world.10 The abundant gas supply is leading many utilities and manufacturers to switch from oil to natural gas as their feedstock, and may lead to new manufacturing in energy intensive industries. Given the previous 40 years of US reliance on energy imports, near energy independence has not resulted in swift regulatory approvals for energy export projects.

Asia remains a growing consumer, particularly with (1) China’s latest Five-Year Plan calling for an increase in natural gas usage, (2) Japan replacing lost nuclear capacity with gas-fired plants, and (3) Indonesia committing to increased gas use for power generation, road vehicles, and ships. The Russian-Chinese pipeline gas deal in 2014 will supply 1,3 Trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of gas per year for 30 years starting in 2018, potentially increasing to 2,1 Tcf per year. The contract price is linked to international crude oil prices on a take-or-pay basis.11 China has 1,115 Tcf of technically recoverable shale gas, and development of domestic reserves is an important part of the government’s natural gas strategy, along with imports of LNG. Middle Eastern, Australian, and North American LNG projects are all vying for a projected 3,1 Tcf per year by 2040 of additional LNG imports to China to meet its anticipated demand growth.

Japan was once one of the largest producers of nuclear generated electricity. Following the meltdown of the Fukushima Dai-ichi reactor on March 11, 2011 and subsequent shutdown of Japan’s other reactors, more than 86 % of Japan’s generation mix is now fossil fuels (coal, LNG, and fuel oil). The Japanese government anticipates bringing back online a few nuclear facilities in 2015. After four years of disruption, nuclear power will return to the mix, though not at the pre-2011 level for some time yet. Japan’s current (2014) energy policy emphasizes energy security, economic efficiency, and greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

European demand for LNG is uncertain given its unsteady economic recovery, global leadership on climate change, and cost advantages for coal. In some cases, LNG buyers with take-or-pay contracts have benefitted by taking delivery and re-exporting cargoes to other markets.

Implications of abundant North America gas supply and lower relative costs are leading some vessel operators with a significant portion of their voyages within ECAs to consider US LNG bunker fuel to be a reasonable fuel solution. Small-scale LNG suppliers need assurance that the LNG bunker fuel demand is real before committing to supply projects which are not export driven.

Regulatory Summary

To meet the growing demand for LNG bunkering, US and Canadian regulatory bodies and international organizations are working to develop safety and environmental standards to help ensure LNG marine fuel transfer operations are conducted safely throughout the global maritime community. Chapters “Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators“, “Guidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators“, and “Guidelines for Bunkering Facility Operators” provide details of the regulations and guidance on implementation.

US regulations for waterfront facilities handling LNG are in effect; however, they are written primarily to address large quantities of LNG imported or exported as cargo. Nevertheless, there is a robust regulatory framework containing requirements that apply when LNG is being transferred between vessels and shore-based structures, including tank trucks and railcars.

There are no Canadian regulations directly addressing LNG bunkering or use of LNG as fuel for vessels; however, Canada is actively studying the issue. In late 2012, the West Coast Marine LNG project (of which ABS was a participant) was launched to study a variety of issues including:

- technology readiness;

- infrastructure options;

- training;

- regulatory requirements;

- and environmental and economic benefits.

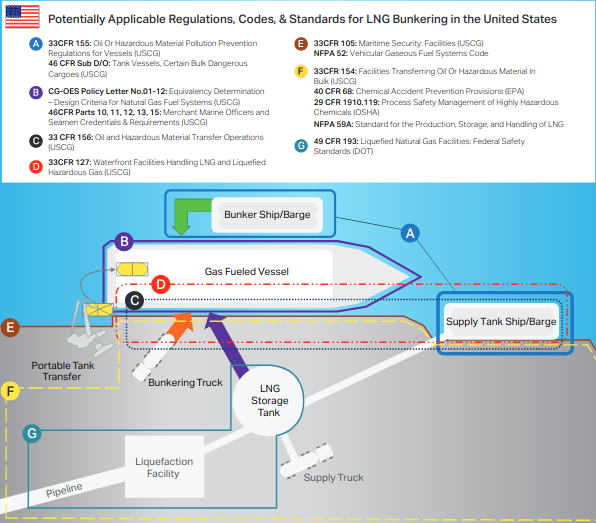

There are international guidelines (e. g., Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators [SIGTTO], Society of Gas as a Marine Fuel [SGMF]) and regulations (e. g., IMOs) that provide guidance for the equipment and operation of natural gas-fueled engine installations on ships. Figure 3 shows potentially applicable regulations, codes and standards for LNG bunkering in the US.

The harmonization of Canadian regulations with international standards has been identified in the Government of Canada’s Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management as a key approach to establishing an effective and appropriate regulatory framework. Transport Canada Marine Safety and Security (TCMSS) is participating at IMOs to ensure Canadian interests are represented as part of the development of international safety requirements. The MSC in their 94th session, approved proposed amendments to make the International Code of Safety for Ships using Gases or other Low-flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code), under Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) with the intent to adopt both the code and SOLAS amendments at the next session, Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) 95, scheduled for June 2015. Until adopted by MSC 95, interim guidance MSC.285(86) will address the safety requirements for these types of vessels. TCMSS is also participating at IMO in the development of a regime for the training and certification of vessel crews and will be taking into consideration the recently released draft International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Bunkering Standard as part of the development of the Canadian domestic regulatory regime. Even without an established Canadian regulatory framework, operators, such as British Columbia Ferries and Chantier Davie Canada, are moving forward with plans to build gas-fueled vessels for operation in Canada.

LNG Bunkering Options

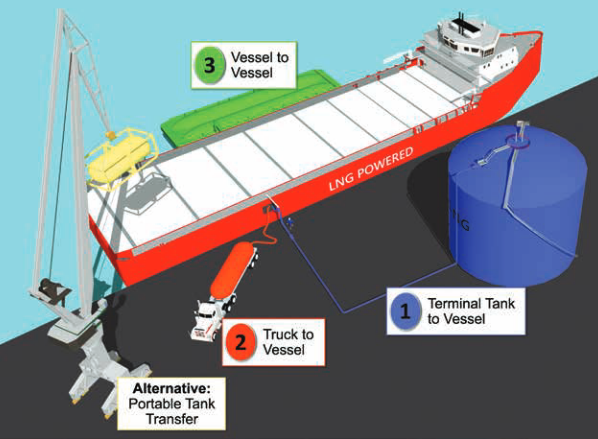

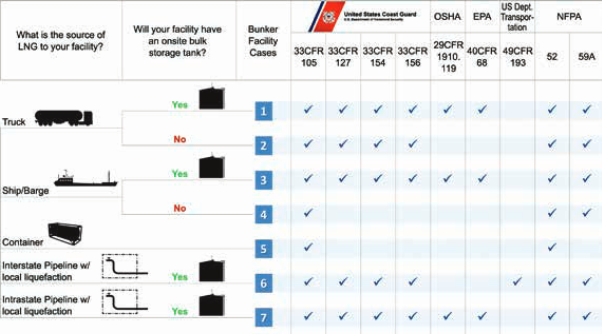

There are multiple options for bunkering LNG on to vessels, depending on how the LNG is sourced and whether or not a bulk storage tank or bunkering vessel is present at the bunkering location. This study considers three general options and an alternative LNG bunkering option (Figure 4).

1 Option 1: Terminal Storage Tank to Vessel: Vessels arrive at a waterfront facility designed to deliver LNG as a fuel to the vessel. Fixed hoses and cranes or dedicated bunkering arms may be used to handle the fueling hoses and connect them to the vessels. Piping manifolds are in place to coordinate fuel delivery from one or more fuel storage tanks

2 Option 2: Truck to Vessel: A tank truck typically consists of a large-frame truck. The mobile facility arrives at a prearranged transfer location and provides hoses that are connected to the truck and to the vessel moored at a dock. Sometimes the hoses are supported on deck and in other arrangements supported from overhead. The transfer usually occurs on a pier or wharf, using a 2-4 inch (0,05-0,1 m) diameter hose.

3 Option 3: Vessel to Vessel: Some marine terminals allow barges to come alongside cargo ships while at their berths, thus allowing cargo to be loaded and the vessel to be fueled at the same time. Vessel fueling can also occur at anchorages. Vessel-to-vessel transfers are the most common form of bunkering for traditional fuel oil.

Alternative Option: Portable Tank Transfer: Some operators are considering using portable LNG tanks (i. e., ISO tanks) as vessel fuel tanks. In this concept, these fuel tanks, when empty, would be replaced by preloaded tanks staged at any facility capable of transferring containers to a vessel moored at the dock. These tanks are modular and can be moved efficiently via truck or rail, and they would be certified to meet the appropriate codes and standards (e. g., American Society of Mechanical Engineers [ASME]/ISO 1496 Pt 3, USCG 46 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] 173).

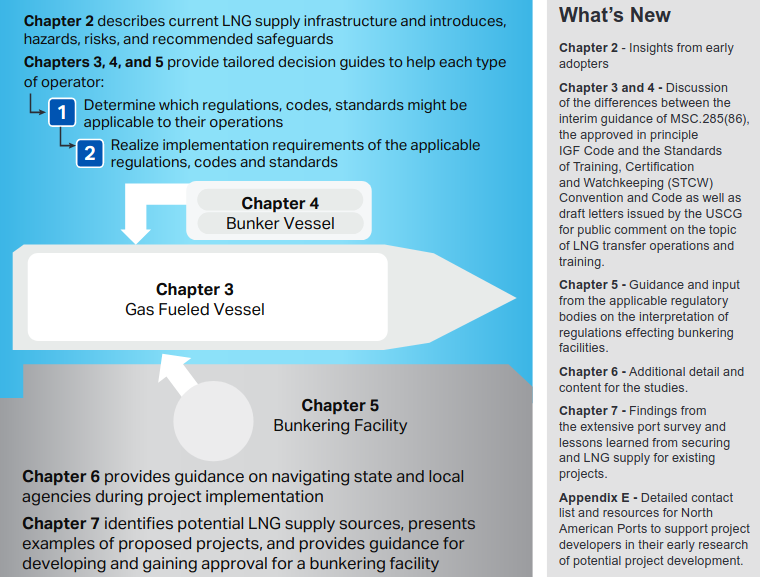

How to Use This Study. This study will help operators and owners of gas-fueled vessels, LNG LNG Operating Regulations Including LNG Bunkering Gothenburg Energy Portbunkering vessels, and waterfront facilities who need background information and guidance to address North American (US and Canada) federal regulations, state/provincial and port requirements, international codes, and standards and potentially waterway requirements or restrictions as well as unique issues such as regional and local restrictions on storing LNG. This section is an overview of the document to help guide owners and operators to the chapter(s) applicable to their operations. It also provides guidance to direct the reader to the new material that is included in this revision of the report.

Chapter 2 is new material for this issue of the report and provides valuable insights and lessons learned from companies that have initiated LNG marine projects and are well underway in their development of LNG-fueled vessels and the corresponding infrastructure for LNG bunkering. LNG bunkering options and LNG hazard and risk information previously included in this chapter are in Chapters “Introduction” above and Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Risk Assessment” respectively.

Chapters “Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators” and “Guidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators“ provide guidelines for vessel operators and project developers. Each chapter provides a decision tree that will guide the user to the applicable regulatory framework. Then for each situation, the specific implementation requirements are tabulated. Chapter “Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators” provides guidelines for gas-fueled vessel operators; Chapter “Guidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators” provides guidelines for bunker vessel operators. The chapters have been updated to highlight and discuss the differences between the interim guidance of MSC.285(86), the approved in principle IGF Code, IGC Code, The Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping (STCW) Convention and Code as well as USCG policy letters issued February 19, 2015 on guidance to the COTP and OCMI’s regarding vessels that use natural gas as fuel and engage in fuel transfer operations as well as guidance to owners of vessels and waterfront facilities intending to conduct liquefied natural gas (LNG) fuel transfer operations.

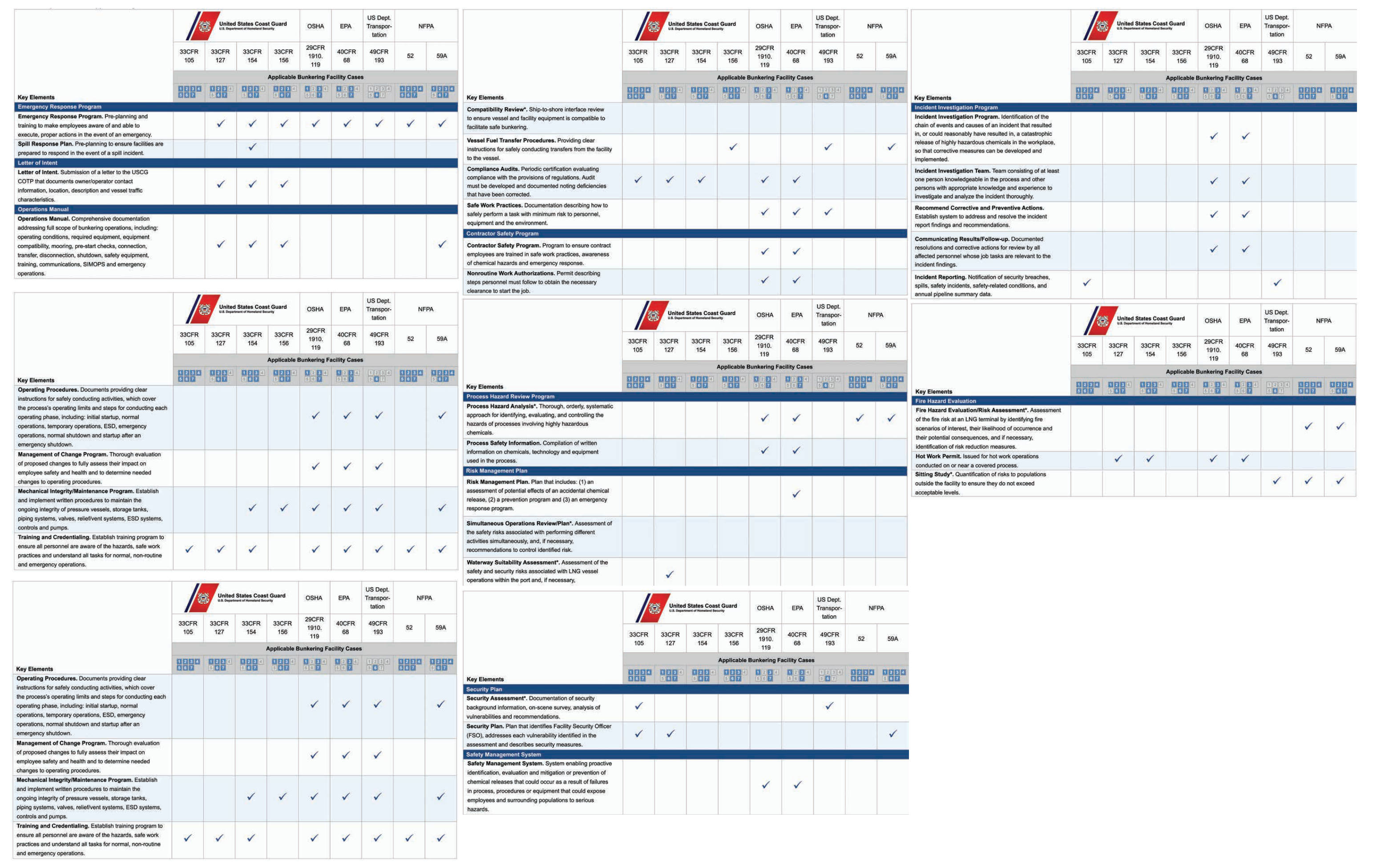

Chapter 5 provides guidelines for bunkering facility operators and has been updated to provide guidance and input from the applicable regulatory bodies on the interpretation of regulations effecting bunkering facilities. Additional clarification on regulatory coverage from OSHA and EPA is provided in this update.

Chapter 6 describes specific studies that, in some cases, may be required in addition to or in support of the regulatory requirements. These studies play an important role in the permitting and approval of LNG bunkering projects and facilities. These sections have been expanded to provide additional detail and content for the studies.

Chapter 7 provides an assessment of the current North American infrastructure to support bunkering operations (1) giving operators information on LNG production in the US and Canada and LNG sources in various geographic regions and (2) providing an overall picture of the present status. It also provides a recommended structured process for implementing an LNG bunkering project, giving consideration to the many local, regional, and port-specific issues that need to be addressed. New material is provided that includes lessons learned and insights gained from securing LNG supply for marine bunkering projects. These include the full range from defining the requirements of the supply to soliciting industry and negotiating contract terms.

Also included in Chapter 7 and Appendix E are the results of a comprehensive survey and discussions with port stakeholders to gain perspectives on the development of LNG projects in North American Ports. Appendix E has been added and provides a comprehensive contact list to support research efforts for potential project developers as they begin the communication tasks with port stakeholders.

Because Canada’s approach to establishing an effective and appropriate LNG bunkering regulatory framework is one of harmonization of Canadian regulations with international standards, an implementation road map, like that of the US, is not currently applicable. For Canada, Chapters 3, 4, and 5 will identify the regulations, codes, and standards that are most relevant to each type of operator, but do not detail the implementation requirements since they do not exist yet.

Project Phases. The primary objective of this report is to provide users with a collection of tools, guidelines and references to aid in the concept and implementation of LNG projects. Included are LNG bunkering facilities, gas-fueled vessels, and LNG bunkering vessels. The enclosed wall-size poster (replicated as Figure 6) provides an overview of the process for each type of project. Cross references to the applicable sections in the report and to key requirements are provided.

Lessons Learned from Early Adopters

Several companies have initiated and are well under way in their development of gas-fueled vessels and the corresponding infrastructure for LNG bunkering. Planning and execution of these projects involved a number of key decisions and resolution of regulatory, commercial and technical issues. The lessons learned from North America’s first adopters of gas-fueled vessels provide valuable insight for future project developers who are considering making an investment in LNG as an alternative marine fuel.

One of the common threads among North America’s early adopters is having gained the awareness that making the switch to LNG requires patience and persistence navigating an uncharted course. When making the decision to build or convert vessels powered by gas, shipowners and operators must consider a number of regulatory factors and address technical challenges associated with applying new technology to their fleets for the first time. The process to develop the first wave of gas-fueled initiatives in North America has required close collaboration, open communication, and shared best practices among classification societies, regulatory bodies such as the USCG and port authorities, vessel designers, and shipyards to establish a baseline for these next-generation vessels.

Key lessons learned from early adopters about making the switch to LNG as a fuel include:

The adoption of LNG as a marine fuel requires a dedicated team. Adoption of the new technologies and addressing the regulations is not a part time job. There is a lot to be considered, reviewed, and engineered and it takes a dedicated team to bring the whole project together.

The drivers for conversion to LNG are both economic and a commitment to environmental stewardship. Economics drive the decision for conversion but the commitment to environmental stewardship on the part of the early adopters weighs significantly in the business case for conversion.

Use trusted advisors and partners to leverage the limited industry experience in gas-fueled vessels. Experience is limited in this emerging industry and the relationships and partnerships used are critical during the transition to LNG fuel.

LNG is readily available for marine bunkering, however, access to (transportation) and traditional bunkering contracts (spot market) are challenges to address when accessing those supplies.

Proper crew training is essential to promote the safe use of LNG as a marine fuel. Just like when making any change within an existing program, training is fundamental. Recognizing this is new technology and personnel are well versed in the old diesel world, resources have to be applied to provide necessary crew training.

Relationship with the Regulators. Early and often dialogue with the regulatory bodies, primarily the USCG, is essential to establishing formal lines of communication at all levels.

Decision to use LNG

The primary drivers for selecting LNG as fuel were competitive pricing in terms of long-term prospects and environmental stewardship and sustainability. Companies view this conversion as a significant step to reduce their carbon footprint, which is a major concern to customers across industry that are prioritizing «greener» ship designs with technology aimed at reducing emissions to the strictest limit within the North American ECA. Because many ships run against demanding schedules requiring no lost time, one of the most effective ways to reduce the carbon footprint is to use fuels that are much more eco-friendly than HFOs.

The amount of time transiting or operating in the ECA is a key factor. Companies are developing specific ECA strategies that consider navigation routes and weather contingencies for gas-fueled fleets. For some shippers, time spent in the ECA ranges from 40 to 100 percent, where calculations indicate that if vessels spend more than 30 percent of their time in the ECA, LNG is worth considering. At least one ship owner envisions LNG fuel capacities large enough to propel vessels in trans-ocean services; eventually eliminating the use of HFO’s altogether.

Another deciding factor is the age of the existing fleet. For newer vessels, the life cycle economics favored conversion at the time of consideration. For older vessels, on the other hand, new-build programs provided the opportunity for LNG construction. Jones Act business creates an expectation of a 30-year life for new-builds. That service life is more maintenance driven as opposed to being driven by heavy construction. Companies who adopt LNG as a fuel should expect to invest more time to maintain and care for their vessels to meet that 30-year life cycle. On the positive side, the use of methane, with its lower carbon content, some of the maintenance intervals move out as much as 80 % longer. With carbon as being the major wear component of any engine, less carbon in the engine causes the wear factor to diminish significantly. Some operators are looking at moving maintenance intervals out on major components as much as 50 %.

In terms of obstacles faced following the initial decision, early adopters unanimously agree that one of the biggest challenges has involved learning the myriad complexities of the operation and project work scope, not only technically, but from a regulatory standpoint; thus requiring a full-time commitment to the project.

Partner Selection & Communication

In the case of shifting to gas-fueled vessels, the industry has had to rely on a synergy from which to draw expertise and understanding about LNG technology. No single person or organization has all the necessary expertise, yet; therefore, the key is to draw on multiple people’s areas of expertise and understanding and to spread the information around to lean on a broader audience for the knowledge needed. For Jones Act vessels specifically, owners preferred to work with people who had designed and built LNG fueled vessels, as opposed to individuals who had minimal LNG background experience.

Effective communication during the design and construction phase between the:

- designer;

- shipyard;

- equipment suppliers;

- owner;

- USCG;

- and class society is critical to ensure the applicable requirements are properly addressed and implemented.

The installation of LNG dual fuel engines and associated systems is well understood in many areas of the world where LNG carriers are under construction; however, the experience with dual fuel engines and LNG systems is limited in the US Relative to the standards and requirements applicable to LNG carriers, the requirements for gas fueled ships are in their infancy. Additionally, the requirements established for one part of the world may not be adequate for the expansion of gas as a marine fuel in another part of the world. All LNG stakeholders should acknowledge that the basic requirements have been established for gas-fueled ships, but all aspects of a new design cannot be foreseen. As such, effective communications among all parties is imperative.

Close coordination and open communication among the organizations also promotes consistency between the reviews and ultimately a better understanding by all parties of the systems, associated hazards, and best practices to promote safety. ABS provides a series of technical training programs aimed to enhance the understanding of the design, operational, and regulatory aspects of using LNG as a fuel. ABS also provides surveyors experienced with LNG systems to the US from other divisions to support the installation, testing, and commissioning of the LNG fuel gas systems.

Vessel Decisions. Owners have made strategic decisions to use proven designs as a foundation and modify the designs as little as possible to accommodate the fuel gas systems and equipment. When possible, using a sister vessel design for which one vessel was already delivered, the project can by simplified and allows the USCG, class society, owner and other partners to focus only on the gaps. Another strategic decision was to select a single service provided for the entire natural gas and power systems consisting of a fueling station, LNG fuel storage tank, vaporizers and associated piping within a tank connection space (cold box), gas valve unit enclosures, generator sets for propulsion and auxiliary power, and the associated control system.

LNG Supply Availability

LNG suppliers are plentiful and there is confidence among them that there is an abundant supply of gas. Shippers often work with outside consultants to arrange for LNG supply and availability. In many respects, the single most important consideration in LNG supply for bunkering is lead time. There is currently no developed spot market for LNG for the volumes that most vessel operators/owners require. Unlike tradition bunker fuel supply, LNG supply and bunker decisions need to be made well in advance of the launch of the vessel, particularly, if new build liquefaction and bunkering facilities are required to meet the need for LNG.

Actual experience in arranging for a gas supply revealed a significant number of creative solutions to provide LNG. Options ranging from local plants to railroad car transportation have been proposed and from a logistics standpoint, local suppliers are preferred so that weather issues do not affect supply.

Shippers prefer buying fuel on the spot market whereas the LNG market is pushing for longer term fuel contracts so there are contract issues to negotiate. Companies are confident they will have a reliable supply of gas and believe with the quantities they are proposing to consume that any number of partners will put a program together that gets the gas liquefied, gets it on a barge and gets it alongside.

Section Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Securing LNG Supply for Bunkering” of this report is new material for this update and provides additional information on securing an LNG supply.

Engaging with Regulators and Stakeholders

Companies are being cautious while operating in the current environment since there are policy letters, but there is no adopted regulation to work to. Regulations are going to come after the fact so companies are trying to maintain constant communication with the USCG and the USCG has made a concerted effort to have one voice, a position appreciated by industry. Industry understands there will be some regulatory differences between the ports, but the USCG is making efforts to have one USCG-wide view so companies do not have to worry about different regulations from port to port.

The USCG has been extremely supportive of the move to gas-fueled vessels and LNG bunkering. They recognize gas-fueled vessels and LNG bunkering is the future and is where business is moving. Accordingly, they want to ensure everything is being done properly and with stakeholder involvement. To ensure this effort, the USCG asked for and received industry’s guidance and input into the policies so that best practices are implemented.

One of the key issues for shippers is whether or not the USCG will allow operators to bunker during cargo operations. Project developers may be moving forward at risk. There will be significant negative economic impacts for running LNG vessels without the ability to bunker during cargo operations. USCG Policy Letter 01-15 dated 19 February 2015, Guidelines for Liquefied Natural Gas Fuel Transfer Operations and Training of Personnel on Vessels Using Natural Gas as Fuel, states that a formal operation risk assessment may be conducted to help determine whether the simultaneous operations may be conducted safely.

The recently issued ISO Technical Specification provides guidance for conducting risk assessments to support bunkering during cargo operations and/or bunkering with passengers on-board or embarking/disembarking. Section Comprehensive Overview of LNG Risk Management“Simultaneous Operations” in this study provides additional guidance on conducting risk assessment for Simultaneous Operations (SIMOPS).

Training. Recognizing this is new technology and personnel are well versed in the diesel world, crews will have to be brought up to speed on the gas side. The IMO Human Element, Training and Watchkeeping (HTW) Sub-Committee developed interim guidance on training for seafarers on ships using gases or other low-flashpoint fuels. This interim guidance provides training for different types of seafarers. The guidelines provide basic and advanced training on the risks and emergency procedures associated with fuels addressed in the IGF Code. Basic and advanced training requirements are outlined in Sections “Operational and Training Requirements for Personne” and “Standards for Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers” for gas fueled vessels and bunker vessels respectively.

Summary. Going forward, each gas fueled ship will have unique challenges. Equipment and solution providers will differ, as such; one solution for a particular vessel may not work on another. However, the experience gained by all parties for the first vessels using LNG as a fuel has the potential to make future projects even more successful.

Several lessons have already been learned and will continue to be learned that may assist others as we enter this era of gas with an inevitable growth of LNG as a fuel. It’s important to remember, shipbuilding is a challenging job for the most basic of ships, but adding new technology to the process requires even more reliance on communication, use of lessons learned, solid partnerships and dedication to the process.

Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators

This chapter provides operational and training guidelines for owners and operators of vessels that will use LNG as fuel. Given the various international and North American regulations, a decision tree guides the reader through the applicable regulatory framework, including interim guidelines that have been established. Specific regulatory requirements and guidelines are discussed to provide gas-fueled operators with a comprehensive means to navigate the operational and training requirements.

International guidelines for natural gas-fueled ships are currently being developed by the IMO. In June 2009, the IMO published interim guidelines outlining the criteria for the arrangement and installation of machinery for propulsion and auxiliary purposes using natural gas as fuel. These guidelines also provided operational and training requirements for personnel working on board gas-fueled ships. The interim guidelines were intended to provide criteria that would provide an equivalent level of safety as that which is achieved with new and comparable conventional oil fueled machinery. Following the publication of the interim guidelines, the IMO MSC continued to work on development of the IGF Code with a view towards incorporating the arrangement and system interim guidelines into the IGF Code.

Since the publication of MSC Resolution MSC.285(86), several actions have occurred to fully adopt the interim guidelines into various IMO Conventions and Codes. In November 2013, the Standards of Training and Watchkeeping Sub-Committee agreed to consider the operational and training guidelines contained in the MSC Resolution MSC.285(86) for future incorporation into the STCW Convention and Code. In November 2014, the MSC approved, in principle, the draft IGF Code, and also approved proposed amendments to make the Code mandatory under SOLAS. It is anticipated that MSC will formally adopt the IGF Code and the SOLAS amendments in June 2015. If adopted, the IGF Code will enter into force in January 2017.

In February 2014, the Sub-Committee on HTW, developed interim guidance on training for seafarers on ships using gases or other low-flashpoint fuels. These interim guidelines supersede the training set out in Resolution MSC.285(86), and were published by IMO in December 2014. On February 19, 2015, the USCG published a policy letter providing guidelines for LNG transfer operations and training of personnel on vessels using natural gas a fuel. Until the IGF Code is adopted as new amendments to SOLAS and the STCW Code, and until incorporated by reference into USCG regulations, owners and operators of US flag and foreign flag vessels operating in North America and using LNG as a fuel should follow the USCG guidelines contained in the February policy letter. The new IGF Code requirements will be effected per a schedule discussed in detail below.

Ship Arrangements and System Design

The MSC approved, in principle, the Code of Safety for Ships Using Gases or Other Low-Flashpoint Fuels, IGF Code, as well as two amendments to SOLAS Chapter II-1:

- One amendment introduces a new Part G which mandates the application of the IGF Code to cargo ships ≥ 500 gt and passenger ships using natural gas fuel; and

- A second amendment revises Part F Regulation 55 to account for the IGF Code requirement that ships using other low-flashpoint fuels (methanol, propane, butane, ethanol, hydrogen, dimethyl ether, etc.) need to comply with the functional requirements of the Code through the alternative design regulation based on an engineering analysis. Operationally-dependent alternatives are not permitted.

If adopted at MSC 95 in June 2015, it is expected that the mandatory provisions will enter into force on January 1, 2017 and will apply to new ships:

- With a building contract placed on or after January 1, 2017; or

- In the absence of a building contract, the keel of which is laid or which is at a similar stage of

construction on or after July 1, 2017; or - Regardless of the building contract or keel laying date, the delivery is on or after January 1,

2020.

Ships which commence a conversion on/after January 1, 2017 to use low-flashpoint fuels or use additional or different low-flashpoint fuels other than those for which it was originally certified, will need to comply with the IGF Code. IMO plans to develop additional parts of the IGF Code to provide detailed requirements for other specific low flashpoint fuels, such as methanol, LPG, etc., at a later date and as industry experience develops. It was clarified the IGF Code is not intended to apply to gas carriers. Currently, low-flashpoint fuel means gaseous or liquid fuel having a flashpoint lower than 60° Celsius (C). However IMO agreed to ask the Sub-committee on Ship Systems and Equipment to review the flashpoint requirements for oil fuel considering a proposal to lower this to 52 °C. That proposal was made by the US and Canada in light of the permissible sulphur content for oil fuels being reduced to 0,10 % m/m for ships operating in any of the four designated ECAs as of January 1, 2015 and that low-sulphur fuels are known to have flashpoints slightly less than 60 °C. Despite the debate around the SOLAS threshold of 60 °C for low flashpoint fuels, it has been recognized by the IGF Code working group that it is not the intent to apply the IGF Code to conventional liquid low flashpoint fuels, such as those permitted under SOLAS II-2/4.2.1.2 in emergency generators at the 43 °C threshold.

The more significant provisions of the Code include:

Risk assessment – is to be conducted to ensure that risks arising from the use of gas-fuel or low-flashpoint fuels affecting persons on board, the environment, the structural strength or the integrity of the ship are addressed. Consideration is to be given to the hazards associated with physical layout, operation and maintenance, following any reasonably foreseeable failure. The scope and methodology of this risk assessment remains to be clarified and individuals authorized access to the CMS Computer Services (IACS) is in the process of developing a unified requirement on this.

Machinery spaces – are to be either «gas safe» (a single failure cannot lead to release of fuel gas) or «ESD–protected» (in the event of an abnormal gas hazard, all non-safe equipment/ignition sources and machinery is automatically shut down while equipment or machinery in use or active during these conditions is to be of a certified safe type). Engines for generating propulsion power and electric power shall be located in two or more machinery spaces.

Fuel system protection – the IGF Code includes deterministic tank location criteria requiring

that tanks are not to be located within:

- B/5 or 11,5 m, whichever is less, from the side shell;

- B/15 or 2,0 m, whichever is less, from of the bottom shell plating; and

- 8 % of the forward length of the ship.

The IGF Code also includes a probabilistic alternative that may permit tank location closer to the side shell with different acceptability threshold values for passenger and cargo ships of 0,02 and 0,04, respectively. As previously decided by the IMO, the location of fuel tanks below accommodations is not excluded, subject to satisfactory risk assessment. Fuel pipes are not to be located less than 800 millimeter (mm) from the ship’s side. Single fuel supply systems are to be fully redundant and segregated so that a leakage in one system does not lead to an unacceptable loss of power.

Limit state design – structural elements of the fuel containment system are to be evaluated with respect to possible failure modes taking into account the possibility of plastic deformation, buckling, fatigue and loss of liquid and gas tightness.

Air locks – direct access between non-hazardous and hazardous spaces is prohibited except where necessary for operational reasons, through a mechanically ventilated air lock with self-closing doors. Such an air lock is also required for accesses between ESD-protected machinery spaces and other enclosed spaces.

Hazardous areas – the IGF Code applies International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) principles for the classification of hazardous areas. It should be noted that the hazardous areas associated with tank relief valve vents are smaller than those in the IGC Code.

Gas detection – is required at ventilation inlets to accommodation and machinery spaces if required by the risk assessment.

Operational and Training Requirements for Personnel

The IMO HTW Sub-Committee developed interim guidance on training for seafarers on ships using gases or other low-flashpoint fuels. This interim guidance provides training for different types of seafarers. All seafarers serving on board ships subject to the IGF Code should receive appropriate ship and equipment specific familiarization as currently required in STCW regulation I/14.5. The guidelines provide additional basic and advanced training on the risks and emergency procedures associated with fuels addressed in the IGF Code. Basic and advanced training should be given by qualified personnel experienced in the handling and characteristics of fuels addressed in the IGF Code. These basic and advanced training requirements are outlined in Table 1.

| Table 1. Crew Member Training Levels | |

|---|---|

| If crew members are… | Then the following training should be conducted |

| Responsible for designated safety duties | Basic Training |

| Masters, engineer officers and all personnel with immediate responsibility for the care and use of fuels and fuel systems | Advanced Training |

Competencies for basic and advanced training, contained in draft amendments to the STCW Code, are found in Table 2.

| Table 2. Standards of Competence | |

|---|---|

| Level of Training | Standards of Competence |

| Basic Training | Receive basic training or instruction so as to: |

| Contribute to the safe operation of a ship subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Take precautions to prevent hazards on a ship subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Apply occupational health and safety precautions and measures. | |

| Carry out firefighting operations on a ship subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Respond to emergencies. | |

| Take precautions to prevent pollution of the environment from the release of fuels found on ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Provide evidence of having achieved the required standards of competence to undertake their duties and responsibilities through: | |

| Demonstration of competence in accordance with the methods and criteria for evaluating competence determined by the Administration; and | |

| Examination or continuous assessment as part of a training program. | |

| Advanced Training | Receive advanced training or instruction so as to: |

| Gain familiarity with physical and chemical properties of fuels aboard ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Operate remote controls of fuel related to propulsion plant and engineering systems and services on ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Be able to safely perform and monitor all operations related to the fuels used on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Plan and monitor safe bunkering, stowage, and securing of the fuel on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Take precautions to prevent pollution of the environment from the release of fuels from ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Monitor and control compliance with legislative requirements. | |

| Take precautions to prevent hazards. | |

| Apply occupational health and safety precautions and measures on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Have knowledge of the prevention, control and firefighting and extinguishing systems on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Provide evidence of having achieved the required standards of competence to undertake their duties and responsibilities through: | |

| Demonstration of competence in accordance with the methods and criteria for evaluating competence determined by the Administration; and | |

| Examination or continuous assessment as part of a training program. | |

Appendix below contains detailed information on the specific knowledge, understanding, and proficiencies being considered by the IMO for each of the competencies listed in Table 2.

Basic Training.

This appendix contains detailed information on the specific knowledge, understanding and proficiencies being considered by the IMO Correspondence Group in Development of the International Code of Safety for Ships using Gases or Log-Flashpoint Fuels, Development of Training and Certification Requirements for Seafarers for Ships Using Gases or Low-flashpoint Fuels for each of the competencies listed in LNG Bunkering Guidelines: Comprehensive Insights and Best Practices for OperatorsSection “Guidelines for Gas-fueled Vessel Operators”, section LNG Bunkering Guidelines: Comprehensive Insights and Best Practices for Operators“Operational and Training Requirements for Personnel” and Table 2.

Table 1 below provides recommended specification of minimum standards of competence in the basic training of personnel aboard ships subject to the IGF Code. These standards are being recommended for all seafarers responsible for designated safety duties on board vessel subject to the IGF Code.

| Table 1. Recommended Minimum Standards of Competence – Basic Training | |

|---|---|

| Competence | Knowledge, Understanding and Proficiency |

| Contribute to the safe operation of a ship subject to the IGF Code | Design and operational characteristics of ships subject to the IGF Code |

| Basic knowledge of ships subject to the IGF Code, their fuel systems and fuel storage systems: | |

| 1. Fuels addressed by the IGF Code | |

| 2. Types of fuel systems subject to the IGF Code | |

| 3. Atmospheric, cryogenic or compressed storage of fuels on board ships subject to their IGF Code | |

| 4. General arrangement of fuel storage systems on board ships subject to the IGF Code | |

| 5. Hazard and Ex-zones and areas | |

| 6. Typical fire safety plan | |

| 7. Monitoring, control and safety systems aboard ships subject to the IGF Code | |

| Basic knowledge of fuels and fuel storage systems’ operations on board ships subject to the IGF Code: | |

| 1. Piping systems and valves | |

| 2. Atmospheric, compressed or cryogenic storage | |

| 3. Relief systems and protection screens | |

| 4. Bunkering systems | |

| 5. Protection against cryogenic accidents | |

| 6. Fuel leak monitoring and detection | |

| Basic knowledge of the physical properties of fuels on board ship subject to the IGF Code, including: | |

| 1. Properties and characteristics | |

| 2. Pressure and temperature, including vapour pressure/ temperature relationship | |

| Knowledge and understanding of safety requirements and safety management on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Take precautions to prevent hazards on a ship subject to the IGF Code | Basic knowledge of the hazards associated with operations on ships subject to the IGF Code, including: |

| 1. Health hazards | |

| 2. Environmental hazards | |

| 3. Reactivity hazards | |

| 4. Corrosion hazards | |

| 5. Ignition, explosion and flammability hazards | |

| 6. Sources of ignition | |

| 7. Electrostatic hazards | |

| 8. Toxicity hazards | |

| 9. Vapour leaks and clouds | |

| 10. Extremely low temperatures | |

| 11. Pressure hazards | |

| 12. Fuel batch differences | |

| Basics knowledge of hazard controls: | |

| 1. Emptying, inerting, drying and monitoring techniques | |

| 2. Anti-static measures | |

| 3. Ventilation | |

| 4. Segregation | |

| 5. Inhibition | |

| 6. Measures to prevent ignition, fire and explosion | |

| 7. Atmospheric control | |

| 8. Gas testing | |

| 9. Protection against cryogenic damages (LNG) | |

| Understanding of fuel characteristics on ships subject to the IGF Code as found on a Safety Data Sheet (SDS). | |

| Apply occupational health and safety precautions and measures | Awareness of function of gas-measuring instruments and similar equipment |

| 1. Gas testing | |

| Proper use of safety equipment and protective devices, including: | |

| 1. Breathing apparatu | |

| 2. Protective clothing | |

| 3. Resuscitators and equipment | |

| Basic knowledge of safe working practices and procedures in accordance with legislation and industry guidelines and personal shipboard safety relevant to ships subject to the IGF Code, including: | |

| 1. Precautions to be taken before entering hazardous spaces and Ex-zones | |

| 2. Precautions to be taken before and during repair and maintenance work | |

| 3. Safety measures for hot and cold work | |

| Basic knowledge of first aid with reference to an SOS | |

| Carry out firefighting operations on a ship subject to the IGF Code | Fire organization and action to be taken on ships subject to the IGF Code. |

| Special hazards associated with fuel systems and fuel handling on ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Firefighting agents and methods used to control and extinguish fires in conjunction with the different fuels found on board ships subject to the IGF Code. | |

| Firefighting system operations | |

| Respond to emergencies | Basic knowledge of emergency procedures, including emergency shutdown |

| Take precautions to prevent pollution of the environment from the release of fuels found on ships subject to the IGF Code. | Basic knowledge of measures to be taken in the event of leakage/spillage of fuels from ships subject to the IGF Code, including the need to: |

| 1. Report relevant information to the responsible persons | |

| 2. Awareness of shipboard spill/leakage response procedures | |

| 3. Awareness of appropriate personal protection when responding to a spill/leakage of fuels addressed by the IGF Code. | |

Advanced Training

Table 2 provides recommended specifications of minimum standards of competence in the advanced training of personnel aboard ships subject to the IGF Code. These standards are being recommended for masters, engineers, officers, and all personnel with immediate responsibility for the care and use of fuels and fuel systems on board vessels subject to the IGF Code.

| Table 2. Recommended Minimum Standards of Competence – Advanced Training | |

|---|---|

| Competence | Knowledge, Understanding and Proficiency |

| Familiarity with physical and chemical properties of fuels aboard ships subject to the IGF Code | Basic knowledge and understanding of simple chemistry and physics and the relevant definitions related to the safe bunkering and use fuels used on board ships subject to the IGF Code, including: 1. The chemical structure of different fuels used on board ships subject to the IGF Code 2. The properties and characteristics of fuels used on board ships subject to the IGF Code, including: 2.1. Simple physical laws 2.2. States of matter 2.3. Liquid and vapour densities 2.4. Boil off and weathering of cryogenic fuels 2.5. Compression and expansion of gases 2.6. Critical pressure and temperature of gases and pressure 2.7. Flashpoint, upper and lower flammable limits, auto-ignition temperature 2.8. Saturated vapour pressure/ reference temperature 2.9. Dewpoint and bubble point 2.10. Hydrate formation 2.11. Combustion properties: heating values 2.12. Methane number/knocking 2.13. Pollutant characteristics of fuels addressed by the IGF Code 3. The properties of single liquids 4. The nature and properties of solutions 5. Thermodynamic units 6. Basic thermodynamic laws and diagrams 7. Properties of materials 8. Effect of low temperature, including brittle fracture, for liquid cryogenic fuels Understanding the information contained in a Safety Data Sheet (SDS) about fuels addressed by the IGF Code |

| Operate remote controls of fuel related to propulsion plant and engineering systems and services on ships subject to the IGF Code | Operating principles of marine power plants and ships’ auxiliary machineryGeneral knowledge of marine engineering terms |

| Ability to safely perform and monitor all operations related to the fuels used on board ships subject to the IGF Code | Design and characteristics of ships subject to the IGF Code Knowledge of ship design, systems, and equipment found on ships subject to the IGF Code, including: 1. Fuel systems for different propulsion engines 2. General arrangement and construction 3. Fuel storage systems on board ships subject to the IGF Code, including materials of construction and insulation 4. Fuel-handling equipment and instrumentations on board ships: 4.1. Fuel pumps and pumping arrangements. 4.2. Fuel pipelines and 4.3. Expansion devices 4.4. Flame screens 4.5. Temperature monitoring systems 4.6. Fuel tank level-gauging systems 4.7. Tank pressure monitoring and control systems5. Cryogenic fuel tanks temperature and pressure maintenance 6. Fuel system atmosphere control systems (inert gas, nitrogen), including storage, generation and distribution 7. Toxic and flammable gas-detecting systems 8. Fuel ESD system Knowledge of fuel system theory and characteristics, including types of fuel system pumps and their safe operation on board ships subject to the IGF Code 1. Low pressure pumps 2. High pressure pumps 3. Vaporizers 4. Heaters 5. Pressure Build-up UnitsKnowledge of safe procedures and checklists for taking fuel tanks in and out of service, including: 1. Inerting 2. Cooling down 3. Initial loading 4. Pressure control 5. Heating of fuel 6. Emptying systems |

| Plan and monitor safe bunkering, stowage and securing of the fuel on board ships subject to the IGF Code | General knowledge of ships subject to the IGF Code Ability to use all data available on board related to bunkering, storage and securing of fuels addressed by the IGF Code Ability to establish clear and concise communications and between the ship and the terminal, truck or the bunker-supply ship Knowledge of safety and emergency procedures for operation of machinery, fuel and control systems for ships subject to the IGF Code Proficiency in the operation of bunkering systems on board ships subject to the IGF Code including: 1. Bunkering procedures 2. Emergency procedures 3. Ship-shore/ship-ship interface 4. Prevention of rolloverProficiency to perform fuel-system measurements and calculations, including: 1. Maximum fill quantity 2. On board quantity (OBQ) 3. Minimum remain on board (ROB) 4. Fuel consumption calculations |

| Take precautions to prevent pollution of the environment from the release of fuels from ships subject to the IGF Code | Knowledge of the effects of pollution on human and environment |

| Monitor and control compliance with legislative requirements | Knowledge and understanding of relevant provisions of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and other relevant IMO instruments, industry guidelines and port regulations as commonly applied. Proficiency in the use of the IGF Code and related documents. |

| Take precautions to prevent hazards | Knowledge and understanding of the hazards and control measures associated with fuel system operations on board ships subject to the IGF Code, including: 1. Flammability 2. Explosion 3. Toxicity 4. Reactivity 5. Corrosivity 6. Health hazards 7. Inert gas composition 8. Electrostatic hazards 9. Pressurized gasesProficiency to calibrate and use monitoring and fuel detection systems, instruments, and equipment on board ships subject to the IGF Code Knowledge and understanding of dangers of noncompliance with relevant rules/regulations Knowledge and understanding of risks assessment method analysis on board ships subject to the IGF Code Ability to elaborate and develop risks analysis related to risks on board ships subject to the IGF Code. Ability to elaborate and develop safety plan and safety instructions for ships subject to the IGF Code. |

| Application of leadership and teamworking skills on board a ship subject to the IGF Code | Ability to apply task and workload management, including: 1. Planning and coordination 2. Personnel assignment 3. Time and resource constraints 4. Prioritization 5. Allocation, assignment and prioritization of resources 6. Effective communication on board and ashoreAbility to ensure the safe management of bunkering and other IGF Code fuel-related operations concurrent with other on board operations, both in port and at sea. |

| Apply occupational health and safety precautions and measures on board a ship subject to the IGF Code | Proper use of safety equipment and protective devices, including: 1. Breathing apparatus and evacuating equipment 2. Protective clothing and equipment 3. Resuscitators 4. Rescue and escape equipmentKnowledge of safe working practices and procedures in accordance with legislation and industry guidelines and personal shipboard safety, including: 1. Precautions to be taken before, during, and after repair and maintenance work on fuel systems addressed in the IGF Code 2. Electrical safety (refer to IEC 600079-17) 3. Ship/shore safety checklist Basic knowledge of first aid with reference to a Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for fuels addressed by the IGF Code. Basic knowledge of first aid with reference to a Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for fuels addressed by the IGF Code. |

| Prevent, control and fight fires on board ships subject to the IGF Code | Methods and firefighting appliances to detect, control and extinguish fires of fuels addressed by the IGF Code. |

| Develop emergency and damage control plans and handle emergency situations on board ships subject to the IGF Code | Ship construction, including damage control Knowledge and understanding of shipboard emergency procedures for ships subject to the IGF Code, including: 1. Ship emergency response plans 2. Emergency shutdown procedure 3. Actions to be taken in the event of failure of systems or services essential to fuel-related operations 4. Enclosed space rescue 5. Emergency fuel system operationsAction to be taken following collision, grounding or spillage and envelopment of the ship in toxic or flammable vapour including: 1. Measures to keep tanks safe and emergency shutdown to avoid ignition of flammable mixtures and to avoid rapid phase transition (RPT) 2. Initial assessment of damage and damage control 3. Safe maneuverer of the ship 4. Precautions for the protection and safety of passengers and crew in emergency situations including evacuation to safe areas 5. Controlled jettisioning of fuel Actions to be taken following envelopment of the ship in flammable fluid or vapour Knowledge of medical first-aid procedures and antidotes on board ships using fuels addressed by the IGF Code reference to the Medical First Aid Guide for Use in Accidents Involving Dangerous Goods (MFAG). |

United States

Existing USCG regulations cover the design, operation and manning of certain type of US flag vessels. However, the USCG has not developed new regulations for the operations and training of personnel on vessels that use LNG as a fuel. The USCG has issued guidance on the design criteria for natural gas fuel systems as well as guidelines for fuel transfer operations and training of personnel on gas-fueled vessels. When the IMO makes the IGF Code mandatory, the USCG may consider requiring full compliance with this Code by incorporating the IGF Code into US regulations. This section lists and describes the current guidelines, rules and codes applicable to US flag gas-fueled vessels and foreign flag gas-fueled vessels operating in US in addition, USCG may define requirements for foreign flag vessels operating in the US in the near future. The current understanding is that for foreign flag vessels the USCG would not require full compliance with the requirements applicable to US flag vessels. However, the USCG would perform an evaluation of the vessel, including the design standards used and approvals obtained by the vessel’s flag state and classification society.

Table 3 lists the current guidelines, rules, and codes related to the use of LNG as a fuel that may be applicable for US flag gas-fueled vessels. In addition to these guidelines, codes and regulations, the owners and operators of vessels using LNG as a fuel will need to comply with existing requirements based on the type of vessel.

| Table 3. Guidelines, Regulations, Codes and Standards unique to Gas-fueled Vessels | ||

|---|---|---|

| IMO | USCG | ABS |

| International Code of Safety for Ships using Gases or other Low flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code) | CG-521 Policy Letter 01-12 Equivalency Determination: Design Criteria for Natural Gas Fuel Systems | Guide for Propulsion and Auxiliary Systems for Gas Fueled Ships |

| IMO STCW.7 Circular 23 – Interim Guidance on Training for Seafarers on Ships using Gases or other Low-flashpoint fuels | CG-OES Policy Letter No. 01-15 Guidelines for Liquefied Natural Gas Fuel Transfer Operations and Training of Personnel on Vessels using Natural Gas as Fuel | Guide for LNG Fuel Ready Vessels |

These existing regulations govern the design, inspection, maintenance, and operations of these vessels, as well as prescribe standards for training, certification of mariners, and the manning of vessels. Additional pollution prevention regulations are contained in Title 33 CFR Subchapter O, which outlines requirements for pollution prevention, especially during transfer operations. These existing requirements, outlined in Table 4, are based on the type of vessel and not necessarily applicable due to the use of LNG as a fuel.

| Table 4. Existing US Coast Guard Regulations for Certain Vessel Types | |

|---|---|

| Vessel Type | US Coast Guard Regulations |

| Towing Vessel | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter C – Parts 24-28 | |

| Fishing Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter C – Parts 24-28 |

| Tank Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter D – Parts 30-39 | |

| Passenger Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter I – Passenger Vessels – Parts 70-80 | |

| Cargo Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter I – Cargo and Miscellaneous Vessels – Parts 90-105 | |

| Small Passenger Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter K – Small Passenger Vessels carrying more than 150 passengers or with overnight accommodations for more than 49 passengers – Parts 114-122 | |

| Offshore Supply Vessels | 46 CFR Subchapter B – Merchant Marine Officers and Seaman – Parts 10-16 |

| 46 CFR Subchapter L – Offshore Supply Vessels – Parts 125-134 | |

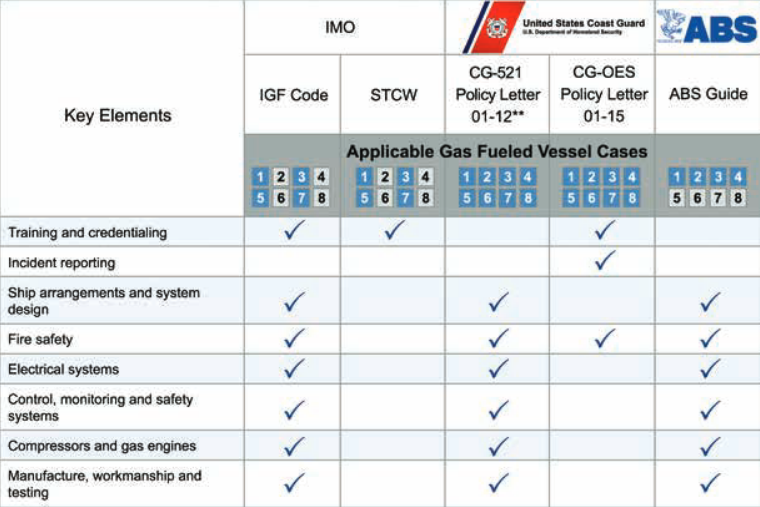

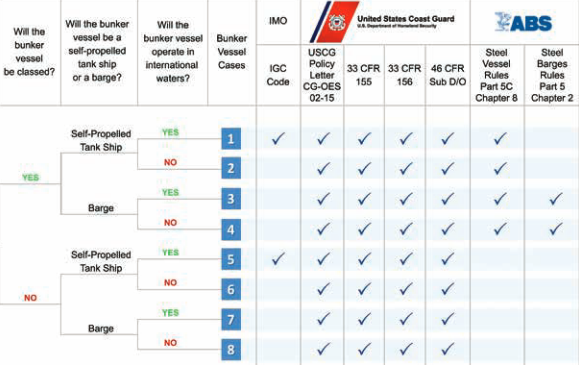

Figure 7 is a simple decision tree to assist vessel operators in identifying the regulations, codes, and standards that may be applicable to their vessels specifically related to the use of LNG gas fuel based on whether the vessel (1) will be classed, (2) will be inspected by the USCG, and (3) will operate in international waters. Note that gas carriers fueled by cargo boil-off are currently regulated by the International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk (IGC Code) and are not a primary focus of this study, with the exception of bunker vessels, which are discussed in Chapter “Guidelines for Bunker Vessel Operators“. Answering those three simple questions categorizes a prospective vessel into one of eight unique gas-fueled vessel cases.

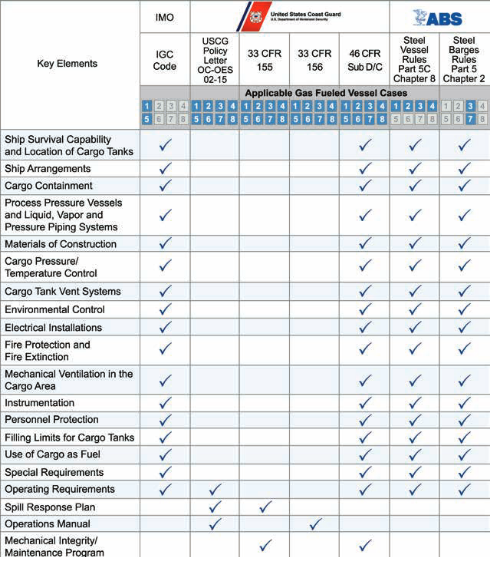

Table 5 presents key elements required under each code, standard, or guideline, and identifies which of the eight gas-fueled cases from Figure 7 are applicable to each key element.

USCG Regulations and Guidelines Specifically for LNG Fueled Vessels

As discussed above and shown in Table 5, certain US flag vessels are subject to existing USCG regulations. However, the use of LNG as a fuel is relatively new among US flag vessels and foreign vessels operating in US waters. While existing USCG regulations apply to LNG fuel transfer operations, the USCG has established equivalency guidelines and has developed interim operating and training guidelines for vessels using LNG as fuel.

US flag vessels that use LNG as a fuel are subject to USCG regulations outlined in various Subchapters of Title 46 CFR. The specific regulations governing these vessels depends on the:

- type of vessel;

- such as towing vessel;

- fishing vessel;

- tank vessel;

- cargo vessel, etc.

The USCG has not established specific regulations for vessels that receive LNG as fuel. In the interim, the USCG published guidance on February 19, 2015 for fuel transfer operations and training of personnel work on vessels that use natural gas as fuel and conduct LNG fuel transfers.

Equivalency Determination: Design Criteria for Natural Gas Fuel Systems – CG-521 Policy Letter 01-12

Existing USCG regulations address the design, equipment, operations, and training of personnel on vessels that carry LNG as cargo in bulk. The regulations also address the fueling systems for boil-off gas used on LNG carriers. However, there are no US regulations explicitly addressing gas-fueled vessels.