The selection of the correct compressor is a critical decision that directly impacts the efficiency, reliability, and capital expenditure of any industrial project, particularly within the challenging domain of natural gas handling and transportation. Engineers and operators are constantly tasked with evaluating the two predominant classes of equipment: positive displacement (reciprocating) and dynamic (centrifugal) machines. Our focus in this comprehensive guide is the Reciprocating and Centrifugal Compressor Comparison for Natural Gas Compression.

- Introduction

- Reciprocating Compressors

- Centrifugal Compressors

- Comparison Between Compressors

- Compressor Selection

- Thermodynamics of Gas Compression

- Real Gas Behavior and Equations of State

- Compression Ratio

- Compression design

- Determining Number of Stages

- Inlet Flow Rate

- Compression Power Calculation

- Compressor Control

- Reciprocating Compressors

- Centrifugal Compressors

- Compressor Performance Maps

- Reciprocating Compressors

- Centrifugal Compressors

Reciprocating compressors are positive displacement machines utilizing a piston’s back-and-forth motion within a cylinder. They are inherently suited for high discharge pressure applications, often exceeding 3 500 bar, and are efficient at managing lower flow rates and variable operating conditions. Conversely, centrifugal compressors are dynamic machines that use impellers to impart kinetic energy to the gas, subsequently converting it into pressure. These units are preferred for very high flow rates, continuous duty cycles, and where minimizing downtime for maintenance is paramount. This article serves as an essential resource, detailing the performance maps, thermodynamic considerations, compression ratio calculations, and design factors necessary to make an informed technical decision regarding your compression needs.

Introduction

“Compression” is used in all aspects of the natural gas industry, including gas lift, reinjection of gas for pressure maintenance, gas gathering, gas processing operations (circulation of gas through the process or system), transmission and distribution systems, and reducing the gas volume for shipment by tankers or for storage. In recent years, there has been a trend toward increasing pipeline-operating pressures. The benefits of operating at higher pressures include the ability to transmit larger volumes of gas through a given size of pipeline, lower transmission losses due to friction, and the capability to transmit gas over long distances without additional boosting stations. In gas transmission, two basic types of compressors are used: reciprocating and centrifugal compressors. Reciprocating compressors are usually driven by either Ship Electrical Systemelectric motors or gas engines, whereas centrifugal compressors use gas turbines or electric motors as drivers.

The key variables for equipment selections are life cycle cost, capital cost, maintenance costs, including overhaul and spare parts, fuel, or energy costs. The units level of utilization, as well as demand fluctuations, plays an important role. While both gas engines and gas turbines can use pipeline gas as a fuel, an electric motor has to rely on the availability of electric power. Due to the number of variables involved, the task of choosing the optimum driver can be quite involved, and a comparison between the different types of drivers should be done before a final selection is made. An economic feasibility study is of fundamental importance to determine the best selection for the economic life of a project. Furthermore, it must be decided whether the compression task should be divided into multiple compressor trains, operating in series or in parallel.

This chapter presents a brief overview of the two major types of compressors and a procedure for calculation of the required compression power, as well as additional and useful considerations for the design of compressor stations. All performance calculations should be based on inlet flange to discharge flange conditions. This means that for centrifugal compressors, the conditions at the inlet flange into the compressor and the discharge flange of the compressor are used. For reciprocating compressors, this means that pressure losses at the cylinder valves, as well as pressure losses in pulsation dampeners, have to be included in the calculation. Additional losses for process equipment such as suction scrubbers or aftercoolers have to be accounted for separately.

Reciprocating Compressors

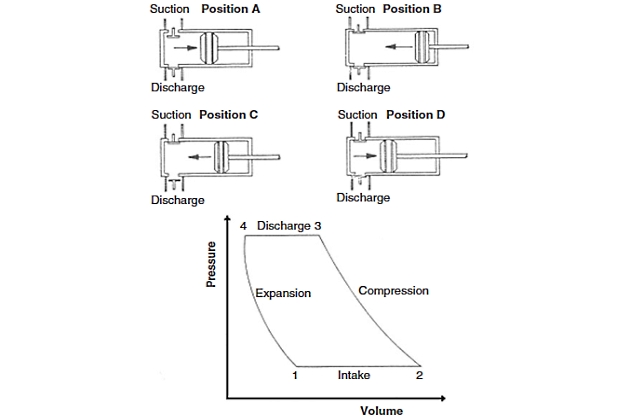

A reciprocating compressor is a positive displacement machine in which the compressing and displacing element is a piston moving linearly within a cylinder. The reciprocating compressor uses automatic spring-loaded valves that open when the proper differential pressure exists across the valve. Figure 1 describes the action of a reciprocating compressor using a theoretical pressure-volume (PV) diagram. In position A, the suction valve is open and gas will flow into the cylinder (from point 1 to point 2 on the PV diagram) until the end of the reverse stroke at point 2, which is the start of compression. At position B, the piston has traveled the full stroke within the cylinder and the cylinder is full of gas at suction pressure. Valves remain closed. The piston begins to move to the left, closing the suction valve. In moving from position B to position C, the piston moves toward the cylinder head, reducing the volume of gas with an accompanying rise in pressure. The PV diagram shows compression from point 2 to point 3. The piston continues to move to the end of the stroke (near the cylinder head) until the cylinder pressure is equal to the discharge pressure and the discharge valve opens (just beyond point 3). After the piston reaches point 4, the discharge valve will close, leaving the clearance space filled with gas at discharge pressure (moving from position C to position D). As the piston reverses its travel, the gas remaining within the cylinder expands (from point 4 to point 1) until it equals suction pressure and the piston is again in position A.

The flow to and from reciprocating compressors is subject to significant pressure fluctuations due to the reciprocating compression process. Therefore, pulsation dampeners have to be installed upstream and downstream of the compressor to avoid damages to other equipment. The pressure losses (several percent of the static flow pressure) of these dampeners have to be accounted for in the station design.

Reciprocating compressors are widely utilized in the gas processing industries because they are flexible in throughput and discharge pressure range. Reciprocating compressors are classified as either “high speed” or “slow speed“. Typically, high-speed compressors operate at speeds of 900 to 1 200 rpm and slow-speed units at speeds of 200 to 600 rpm. High-speed units are normally “separable“, i. e., the compressor frame and driver are separated by a coupling or gearbox. For an “integral” unit, power cylinders are mounted on the same frame as the compressor cylinders, and power pistons are attached to the same drive shaft as the compressor cylinders. Low-speed units are typically integral in design.

Centrifugal Compressors

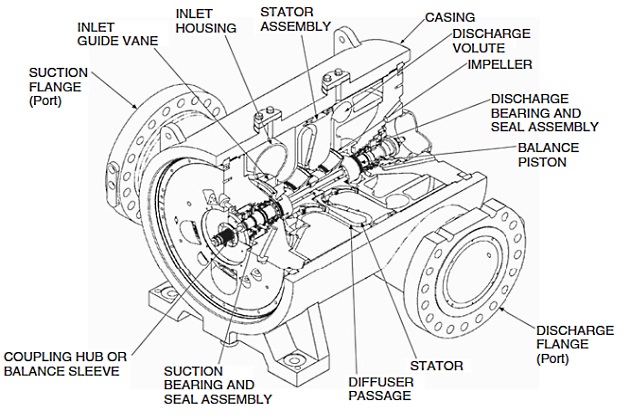

We want to introduce now the essential components of a centrifugal compressor that accomplish the tasks specified earlier (Figure 2).

The gas entering the inlet nozzle of the compressor is guided to the inlet of the impeller. An impeller consists of a number of rotating vanes that impart mechanical energy to the gas. The gas will leave the impeller with an increased velocity and increased static pressure. In the diffuser, part of the velocity is converted into static pressure. Diffusers can be vaned, vaneless, or volute type. If the compressor has more than one impeller, the gas will be again brought in front of the next impeller through the return channel and the return vanes. If the compressor has only one impeller, or after the diffuser of the last impeller in a multistage compressor, the gas enters the discharge system. The discharge system can either make use of a volute, which can further convert velocity into static pressure, or a simple cavity that collects the gas before it exits the compressor through the discharge flange.

Read also: The Role of SIGTTO LNG Safety in Advancing Industry Standards

The rotating part of the compressor consists of all the impellers. It runs on two radial bearings (on all modern compressors, these are hydrodynamic tilt pad bearings), while the axial thrust generated by the impellers is balanced by a balance piston, and the resulting force is balanced by a hydrodynamic tilt pad thrust bearing. To keep the gas from escaping at the shaft ends, dry gas seals are used. The entire assembly is contained in a casing (usually barrel type).

A compressor stage is defined as one impeller, with the subsequent diffuser and (if applicable) return channel. A compressor body may hold one or several (up to 8 or 10) stages. A compressor train may consist of one or multiple compressor bodies. It sometimes also includes a gearbox. Pipeline compressors are typically single body trains, with one or two stages.

The different working principles cause differences in the operating characteristics of the centrifugal compressors compared to those of the reciprocating unit. Centrifugal compressors are used in a wide variety of applications in chemical plants, refineries, onshore and offshore gas lift and gas injection applications, gas gathering, and in the transmission of Understanding the Fundamentals of US Natural Gas Pricing and Market Volatilitynatural gas. Centrifugal compressors can be used for outlet pressures as high as 10 000 psia, thus overlapping with reciprocating compressors over a portion of the flow rate/pressure domain. Centrifugal compressors are usually either turbine or electric motor driven. Typical operating speeds for centrifugal compressors in gas transmission applications are about 14 000 rpm for 5 000-hp units and 8 000 rpm for 20 000-hp units.

Comparison Between Compressors

Differences between reciprocating and centrifugal compressors are summarized as follow.

Advantages of a reciprocating compressor over a centrifugal machine include:

- Ideal for low volume flow and high-pressure ratios.

- High efficiency at high-pressure ratios.

- Relatively low capital cost in small units (less than 3 000 hp).

- Less sensitive to changes in composition and density.

Advantages of a centrifugal compressor over a reciprocating machine include:

- Ideal for high volume flow and low head.

- Simple construction with only one moving part.

- High efficiency over normal operating range.

- Low maintenance cost and high availability.

- Greater volume capacity per unit of plot area.

- No vibrations and pulsations generated.

Compressor Selection

The design philosophy for choosing a compressor should include the following considerations.

- Good efficiency over a wide range of operating conditions.

- Maximum flexibility of configuration.

- Low maintenance cost.

- Low life cycle cost.

- Acceptable capital cost.

- High availability.

However, additional requirements and features will depend on each project and on specific experiences of the Pipelines in Marine Terminals: Key Considerations for Handling Liquefied Gaspipeline operator. In fact, compressor selection consists of the purchaser defining the operating parameters for which the machine will be designed. The “process design parameters” that specify a selection are as follows.

1 Flow rate.

2 Gas composition.

3 Inlet pressure and temperature.

4 Outlet pressure.

5 Train arrangement:

- For centrifugal compressors: series, parallel, multiple bodies, multiple sections, intercooling, etc.

- For reciprocating compressors: number of cylinders, cooling, and flow control strategy.

6 Number of units.

In many cases, the decision whether to use a reciprocating compressor or a centrifugal compressor, as well as the type of driver, will already have been made based on operator strategy, emissions requirements, general life cycle cost assumptions, and so on. However, a hydraulic analysis should be made for each compressor selection to ensure the best choice.

In fact, compressor selection can be made for an operating point that will be the most likely or most frequent operating point of the machine. Selections based on a single operating point have to be evaluated carefully to provide sufficient speed margin (typically 3 to 10 %) and surge margin to cover other, potentially important situations. A compressor performance map (for centrifugal compressors, this would be preferably a head vs flow map) can be generated based on the selection and is used to evaluate the compressor for other operating conditions by determining the head and flow required for these other operating conditions. In many applications, multiple operating points are available, e. g., based on hydraulic pipeline studies or reservoir studies. Some of these points may be frequent operating points, while some may just occur during upset conditions. With this knowledge, the selection can be optimized for a desired target, such as lowest fuel consumption.

It will be interesting: Understanding Liquefied Gas Manifolds – Size Categories, Positioning, and Specific Designs for LPG & LNG

Selections can also be made based on a “rated” point, which defines the most onerous operating conditions (highest volumetric flow rate; lowest molecular weight; highest head or pressure ratio; highest inlet temperature). In this situation, however, the result may be an oversized machine that does not perform well at the usual operating conditions.

Once a selection is made, the manufacturer is able to provide parameters such as efficiency, speed, and power requirements and, based on this and the knowledge of the ambient conditions (prevailing temperatures, elevation), can size the drivers. At this point, the casing arrangement and the number of units necessary or desirable (flexibility requirements, growth scenarios and sparing considerations will play an important role in this decision) can be discussed.

Thermodynamics of Gas Compression

The task of gas compression is to bring gas from a certain suction pressure to a higher discharge pressure by means of mechanical work. The actual compression process is often compared to one of three ideal processes: isothermal, isentropic, and polytropic compression.

Isothermal compression occurs when the temperature is kept constant during the compression process. It is not adiabatic because the heat generated in the compression process has to be removed from the system.

The compression process is isentropic or adiabatic reversible if no heat is added to or removed from the gas during compression and the process is frictionless. With these assumptions, the entropy of the gas does not change during the compression process.

The polytropic compression process is like the isentropic cycle reversible, but it is not adiabatic. It can be described as an infinite number of isentropic steps, each interrupted by isobaric heat transfer. This heat addition guarantees that the process will yield the same discharge temperature as the real process.

It is important to clarify certain properties at this time and, in particular, find their connection to the first and second law of thermodynamics written for steady-state fluid flows. The first law (defining the conservation of energy) becomes:

where:

- h – is enthalpy;

- u – is velocity;

- g – is gravitational acceleration;

- z – is elevation coordinate;

- q – is heat;

- and Wt – is work done by the compressor on the gas.

Neglecting the changes in potential energy (because the contribution due to changes in elevation is not significant for Usage of Natural Gas Compressors in the Gas Production Operationsgas compressors), the energy balance equation for adiabatic processes (q12 = 0) can be written as:

Wt, 12 is the amount of work Physically, there is no difference among work, head, and change in enthalpy. In systems with consistent units (such as the SI system), work, head, and enthalpy difference, have the same unit (e. g., kJ/kg in SI units). Only in inconsistent systems (such as US customary units) do we need to consider that the enthalpy difference (e. g., in Btu/lbm) is related to head and work (e. g., in ft.lbf /lbm) by the mechanical equivalent of heat (e. g., in ft.lbf /Btu).x we have to apply to affect the change in enthalpy in the gas. The work Wt, 12 is related to the required power, P, by multiplying it with the mass flow.

Combining enthalpy and velocity into a total enthalpy (

), power and total enthalpy difference are thus related by:

If we can find a relationship that combines enthalpy with the pressure and temperature of a gas, we have found the necessary tools to describe the gas compression process. For a perfect gas, with constant heat capacity, the relationship among enthalpy, pressures, and temperatures is:

where:

- T1 – is suction temperature;

- T2 – is discharge temperature;

- and Cp – is heat capacity at constant pressure.

For an isentropic compression, the discharge temperature (T2s) is determined by the pressure ratio as:

where:

- k = Cp/Cv, p1 – is suction pressure;

- and p2 – is discharge pressure.

Note that the specific heat at constant pressure (Cp) and the specific heat at constant volume (Cv) are functions of temperature only for ideal gases and can be related together with Cp − Cv = R, where R is the universal gas constant. The isentropic exponent (k) for ideal gas mixtures can also be determined as:

where:

- Cpi – is the molar heat capacity of the individual component;

- and yi – is the molar concentration of the component.

The heat capacities of real gases are a function of the pressure and temperature and thus may differ from the ideal gas case. For hand calculations, the ideal gas k is sufficiently accurate.

If the Chemical Composition and Physical Properties of Liquefied Gasesgas composition is not known, and the gas is made up of alkanes (such as methane and ethane) with no substantial quantities of contaminants and whose specific gravity (SG) does not exceed unity, the following empirical correlation can be used.

Combining Equations 5 and 6, the isentropic head (∆hs) for the isentropic compression of a perfect gas can thus be determined as:

For real gases [where k and Cp in Equation 9 become functions of temperature and pressure], the enthalpy of a gas, h, is calculated in a more complicated way using equations of state. These represent relationships that allow one to calculate the enthalpy of gas of known composition if any two of its pressure, its temperature, or its entropy are known.

We therefore can calculate the actual head for the compression by:

and the isentropic head by:

where entropy of the gas at suction condition (s1) is:

The relationships described can be seen easily in a Mollier diagram (Figure 3).

The performance quality of a compressor can be assessed by comparing the actual head (which relates directly to the amount of power we need to spend for the compression) with the head that the ideal, isentropic compression would require. This defines the isentropic efficiency (ηs) as:

For ideal gases, the actual head can be calculated from:

and further, the actual discharge temperature (T2) becomes

The second law of thermodynamics tells us:

For adiabatic flows, where no heat q enters or leaves, the change in entropy simply describes the losses generated in the compression process. These losses come from the friction of gas with solid surfaces and the mixing of gas of different energy levels. An adiabatic, reversible compression process therefore does not change the entropy of the system, it is isentropic.

Our equation for the actual head implicitly includes the entropy rise ∆s, because:

If cooling is applied during the compression process (e. g., with intercoolers between two compressors in series), then the increase in entropy is smaller than for an uncooled process. Therefore, the power requirement will be reduced.

Using the polytropic process for comparison reasons works fundamentally the same way as using the isentropic process for comparison reasons. The difference lies in the fact that the polytropic process uses the same discharge temperature as the actual process, while the isentropic process has a different (lower) discharge temperature than the actual process for the same compression task. In particular, both the isentropic and the polytropic processes are reversible processes.

The isentropic process is also adiabatic, whereas the polytropic processes assumes a specific amount of heat transfer. In order to fully define the isentropic compression process for a given gas, suction pressure, suction temperature, and discharge pressure have to be known. To define the polytropic process, in addition either the polytropic compression efficiency or the discharge temperature has to be known. The polytropic efficiency (ηp) is constant for any infinitesimally small compression step, which then allows us to write:

where:

- v – is specific volume, and the polytropic head (∆hp) can be calculated from:

This determines the polytropic efficiency as:

For compressor designers, the polytropic efficiency has an important advantage. If a compressor has five stages, and each stage has the same isentropic efficiency ηs, then the overall isentropic compressor efficiency will be lower than ηs. If, for the same example, we assume that each stage has the same polytropic efficiency ηp, then the polytropic efficiency of the entire machine is also ηp. As far as performance calculations are concerned, the approach either using a polytropic head and efficiency or using isentropic head and efficiency will lead to the same result:

We also encounter energy conservation on a different level in turbomachines. The aerodynamic function of a turbomachine relies on the capability to trade two forms of energy: kinetic energy (velocity energy) and potential energy (pressure energy), as was outlined earlier.

Real Gas Behavior and Equations of State

Understanding gas compression requires an understanding of the relationship among pressure, temperature, and density of a gas. An ideal gas exhibits the following behavior:

where:

- ρ – is the density of gas;

- and R – is the gas constant.

Any gas at very low pressures (p → 0) can be described by this equation.

For the elevated pressures found in natural gas compression, this equation becomes inaccurate, and an additional variable, the compressibility factor (Z), has to be added:

Unfortunately, the compressibility factor itself is a function of pressure, temperature, and gas composition.

A similar situation arises when the enthalpy has to be calculated. For an ideal gas, we find:

where:

- Cp – is only a function of temperature.

This is a better approximation of the reality than the assumption of a perfect gas used in Equation 5.

In a real gas, we get additional terms for the deviation between real gas behavior and ideal gas behavior:

The terms [h0 – h(p1)]T1 and [h0 – h(p2)]T2 are called departure functions because they describe the deviation of real gas behavior from ideal gas behavior. They relate the enthalpy at some pressure and temperature to a reference state at low pressure, but at the same temperature. The departure functions can be calculated solely from an equation of state, while the term ∫ CpdT is evaluated in the ideal gas state.

Equations of state are semiempirical relationships that allow one to calculate the compressibility factor as well as the departure function. For gas compression applications, the most frequently used equations of state are Redlich – Kwong, Soave – Redlich – Kwong, Benedict – Webb – Rubin, Benedict – Webb – Rubin – Starling and Lee – Kessler – Ploecker.

Kumar et al. and Beinecke and Luedtke have compared these equations of state regarding their accuracy for compression applications. In general, all of these equations provide accurate results for typical applications in pipelines, i. e., for gases with a high methane content, and at pressures below about 3 500 psia. It should be noted that the Redlich-Kwong equation of state is the most effective equation from a computational point of view (because the solution is found directly rather than through an iteration).

Compression Ratio

The compression ratio (CR) is the ratio of absolute discharge pressure to the absolute suction pressure. Mathematically

By definition, the compression ratio is always greater than one. If there are “n” stages of compression and the compression ratio is equal on each stage, then the compression ratio per stage is given by:

If the compression ratio is not equal on each stage, then Equation 26 should be applied to each stage.

The term compression ratio can be applied to a single stage of compression and multistage compression. When applied to a single compressor or a single stage of compression, it is defined as the stage or unit compression ratio; when applied to a multistage compressor it is defined as the overall compression ratio. The compression ratio for typical Velocity Criteria for Sizing Multiphase Pipelinesgas pipeline compressors is rather low (usually below 2), except for stations that feed into pipelines. These low-pressure ratios can be covered in a single compression stage for reciprocating compressor and in a single body (with one or two impellers) in a centrifugal compressor.

While the pressure ratio is a valuable indicator for reciprocating compressors, the pressure ratio that a given centrifugal compressor can achieve depends primarily on gas composition and gas temperature. The centrifugal compressor is better characterized by its capability to achieve a certain amount of head (and a certain amount of head per stage). From Equation 9 it follows that the compressor head translates into a pressure ratio depending on gas composition and suction temperature. For natural gas (SG = 0,58 – 0,65), a single centrifugal stage can provide a pressure ratio of 1,4. The same stage would yield a pressure ratio of about 1,6 if it would compress air (SG = 1,0). The pressure ratio per stage is usually lower than the values given earlier for multistage machines.

Read also: LNG Developments – Key Milestones and Challenges in the Sector

For reciprocating compressors, the pressure ratio per compressor is usually limited by mechanical considerations (rod load) and temperature limitations. Reciprocating compressors can achieve cylinder pressure ratios of 3 to 6. The actual flange-to-flange ratio will be (due to the losses in valves and bottles) lower. For lighter gases (such as natural gas), the temperature limit will often limit the pressure ratio before the mechanical limits do. Centrifugal compressors are also limited by mechanical considerations (rotordynamics, maximum speed) and temperature limits. Whenever any limitation is involved, it becomes necessary to use multiple compression stages in series and intercooling. Furthermore, multistage compression may be required from a purely optimization standpoint. For example, with an increasing compression ratio, compression efficiency decreases and mechanical stress and temperature problems become more severe.

For pressure ratios higher than 3, it may be advantageous to install intercoolers between the compressors. Intercoolers are generally used between the stages to reduce the power requirements as well as to lower the gas temperature that may become undesirably high. After the cooling, liquids may form. These liquids are removed in interstage scrubbers or knockout drums.x Theoretically, a minimum power requirement is obtained with perfect intercooling and no pressure loss between stages by making the ratio of compression the same in all stages. However, intercoolers invariably cause pressure losses (typically between 5 and 15 psi), which is a function of the cooler design.

In the preliminary design, the pressure should be on the order of 10 psi for coolers (especially gas-to-air coolers, where the economics may be out of balance for lower pressure drop).

Note that an actual compressor with an infinite number of compression stages and intercoolers would approach isothermal conditions (where the power requirement of compression cycle is the absolutely minimum power necessary to compress the gas) if the gas were cooled to the initial temperature in the intercoolers.

Interstage cooling is usually achieved using gas-to-air coolers. The gas outlet temperature depends on the ambient air temperature. The intercooler exit temperature is determined by the cooling media. If ambient air is used, the cooler exit temperature, and thus the suction temperature to the second stage, will be about 20 to 30 °F above the ambient dry bulb temperature. Water coolers can achieve exit temperatures about 20 °F above the water supply temperature, but require a constant supply of cooling water. Cooling towers can provide water supply temperatures of about wet bulb temperature plus 25 °F.

For applications where the compressor discharge temperature is above some temperature limit of downstream equipment (a typical example is pipe coatings that limit gas temperatures to about 125 to 140 °F) or has to be limited for other reasons (e. g., to not disturb the permafrost), an aftercooler has to be installed.

Compression design

Compressor design involves several steps. These include selection of the correct type of compressor, as well as the number of stages required. In addition, depending on the capacity, there is also a need to determine the horsepower requirement for the compression.

Determining Number of Stages

For reciprocating compressors, the number of stages is determined from the overall compression ratio as follows.

- Calculate the overall compression ratio. If the compression ratio is under 4, consider using one stage. If it is not, select an initial number of stages so that CR < 4. For initial calculations it can be assumed that the compression ratio per stage is equal for each stage. Compression ratios of 6 can be achieved for low-pressure applications, however, at the cost of higher mechanical stress levels and lower volumetric efficiency.

- Calculate the discharge gas temperature for the first stage. If the discharge temperature is too high (more than 300 °F), either increase the number of stages or reduce the suction temperature through precooling. It is recommended that the compressors be sized so that the discharge temperatures for all stages of compression be below 300 °F. It is also suggested that the aerial gas coolers be designed to have a maximum of 20 °F approach to ambient, provided the design reduces the suction temperature for the second stage, conserving horsepower and reducing power demand. If the suction gas temperature to each stage cannot be decreased, increase the number of stages by one and recalculate the discharge temperature.

Note that the 300 °F temperature limit is used for reciprocating compressors because the packing life gets shortened above about 250 °F and the lube oil, being involved directly in the compression process, will degrade faster at higher temperatures. The 350 °F temperature limit pertains to centrifugals and is really a limit for the seals (although special seals can go to 400 to 450 °F) or the pressure rating of casings and flanges. Because the lube oil in a centrifugal compressor does not come into direct contact with the process gas, lube oil degradation is not a factor.

If oxygen is present in the process gas in the amount that it can support combustion (i. e., the gas-to-oxygen ratio is above the lower explosive limit), much lower gas temperatures than mentioned earlier are required.

In reciprocating machines, oil-free compression may be required (no lube oil can come into contact with the process gas). This requires special piston designs that can run dry. Also, a special precaution has to be taken to avoid hot spots generated by local friction.

Inlet Flow Rate

The compressor capacity is a critical component in determining the suitability of a particular compressor. We can calculate the actual gas flow rate While the sizing of the compressor is driven by the actual volumetric flow rate (QG), the flow in many applications is often defined as standard flow. Standard flow is volumetric flow at certain, defined conditions of temperature and pressure (60 °F or 519,7 °R and 14,696 psia) that are usually not the pressures and temperatures of the gas as it enters the compressor.x at suction conditions using:

where:

- QG represents an actual cubic feet per minute flow rate of gas;

- T1 represents the suction temperature in °R;

- p1 represents suction pressure in psia;

- and QG, SC represents the standard volumetric flow rate of gas in MMSCFD.

Note that using the value of actual gas volumetric flow rate and discharge pressure, we can roughly determine the type of compressor appropriate for a particular application. Although there is a significant overlap, however, some of the secondary considerations, such as reliability, availability of maintenance, reputation of vendor, and price, will allow one to choose one of the acceptable compressors.

Compression Power Calculation

Once we have an idea about the type of compressor we will select, we also need to know the power requirements so that an appropriate prime mover can be designed for the job. After the gas horsepower (GHP) has been determined by either method, horsepower losses due to friction in bearings, seals, and speed increasing gears must be added. Bearings and seal losses can be estimated from Scheel’s equation. For reciprocating compressors, the mechanical and internal friction losses can range from about 3 to 8 % of the design gas horsepower. For centrifugal compressors, a good estimate is to use 1 to 2 % of the design GHP as mechanical loss.

To calculate brake horsepower (BHP), the following equation can be used.

The detailed calculation of brake horsepower depends on the choice of type of compressor and number of stages. The brake horsepower per stage can be determined from Equation 30:

where:

- BHP – is brake horsepower per stage;

- Zave – is average compressibility factor;

- QG,SC – is standard volumetric flow rate of gas, MMSCFD;

- T1 – is suction temperature, ◦R;

- p1, p2 are pressure at suction and discharge flanges, respectively, psia;

- E – is parasitic efficiency (for high-speed reciprocating units, use 0,72 to 0,82; for low-speed reciprocating units, use 0,72 to 0,85; and for centrifugal units, use 0,99);

- η – is compression efficiency (1,0 for reciprocating and 0,80 to 0,87 for centrifugal units).

In Equation 30, parasitic efficiency (E) accounts for mechanical losses, and the pressure losses incurred in the valves and pulsation dampeners of reciprocating compressors (the lower efficiencies are usually associated with low-pressure ratio applications typical for pipeline compression). Many calculation procedures for reciprocating compressors use numbers for E that are higher than the ones referenced here. These calculations require, however, that the flange-to-flange pressure ratio [which is used in Equation 30] is increased by the pressure losses in the compressor suction and discharge valves, and pulsation dampeners. These pressure losses are significant, especially for low head, high flow applications.x

Hence, suction and discharge pressures may have to be adjusted for the pressure losses incurred in the pulsation dampeners for reciprocation compressors. The compression efficiency accounts for the actual compression process. For centrifugal compressors, the lower efficiency is usually associated with pressure ratios of 3 and higher. Very low flow compressors (below 1 000 acfm) may have lower efficiencies.

It will be interesting: Comprehensive Guide to Local Content Policies and Infrastructure Development

The total horsepower for the compressor is the sum of the horsepower required for each stage. Reciprocating compressors require an allowance for interstage pressure losses. It can be assumed that there is a 3 % loss of pressure in going through the cooler, scrubbers, piping, and so on between the actual discharge of the cylinder and the actual suction of the next cylinder. For a centrifugal compressor, any losses incurred between the stages are already included in the stage efficiency. However, the exit temperature from the previous stage becomes the inlet temperature in the next stage. If multiple bodies are used, the losses for coolers and piping have to be included as described previously.

Example

Given the following information for a centrifugal compressor, answer the following questions.

Operating Conditions

- Ps = 750 psia;

- Pd = 1046,4 psia;

- Ts = 529,7 °R;

- Td = 582,6 °R;

- QG, SC = 349 MMSCFD.

Gas Properties

- SG = 0,6;

- k = 1,3;

- Zave = 0,95

Questions

- What is the isentropic efficiency?

- What is the actual volumetric flow rate?

- What is the isentropic head?

- What is the power requirement (assume a 98 % mechanical efficiency)?

Solution

1 With rearranging Equation 15, we find:

2 Mass flow is:

and thus the volumetric flow becomes

3 The isentropic head follows from Equation 9 with Cp = (53,35/SG) Z k/(k−1)

4 The power can be calculated from Equation 30

Compressor Control

To a large extent, the compressor operating point will be the result of the pressure conditions imposed by the system. However, the pressures imposed by the system may in turn be dependent on the flow. Only if the conditions fall outside the operating limits of the compressor (e. g., frame loads, discharge temperature, available driver power, surge, choke, speed), do control mechanisms have to be in place. However, the compressor output may have to be controlled to match the system demand.

The type of application often determines the system behavior. In a pipeline application, suction and discharge pressure are connected with the flow by the fact that the more flow is pushed through a pipeline, the more pressure ratio is required at the compressor station to compensate for the pipeline pressure losses. In processelated applications, the suction pressure may be fixed by a back pressure-controlled production separator.

In boost applications, the discharge pressure is determined by the pressure level of the pipeline the compressor feeds into, whereas the suction pressure is fixed by the process. In oil and gas field applications, the suction pressure may depend on the flow because the more gas is moved out of the gas reservoir, the lower the suction pressure has to be. The operation may require constant flow despite changes in suction or discharge pressure. Compressor flow, pressure, or speed may have to be controlled.

The type of control also depends on the compressor driver. Both reciprocating compressors and centrifugal compressors can be controlled by suction throttling or recirculating of gas. However, either method is very inefficient for process control (but may be used to protect the compressor) because the reduction in flow or head is not accompanied by a significant reduction in the power requirement.

Reciprocating Compressors

The following mechanisms may be used to control the capacity of reciprocating compressors:

- suction pressure,

- variation of clearance,

- speed,

- valve unloading,

- and recycle.

Reciprocating compressors tend to have a rather steep head versus flow characteristic. This means that changes in pressure ratio have a very small effect on the actual flow through the machine.

Read also: Mastering Natural Gas Fundamentals Properties Sources and Transport Insights

Controlling the flow through the compressor can be accomplished by varying the operating speed of the compressor. This method can be used if the compressor is driven by an internal combustion engine or a variable speed electric motor. Internal combustion engines, along with variable speed electric motors, produce less power if they operate at a speed different from their optimum speed. Internal combustion engines allow for speed control in the range of 70 to 100 % of maximum speed.

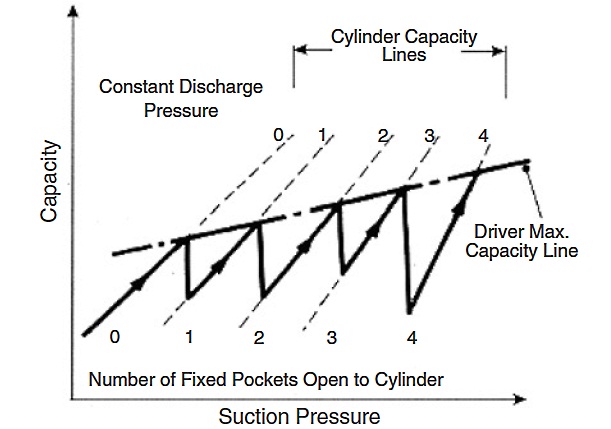

If the driver is a constant speed electric motor, the capacity control consists of either inlet valve unloaders or clearance unloaders. Inlet valve unloaders can hold the inlet valve into the compressor open, thereby preventing compression. Clearance unloaders consist of pockets that are opened when unloading is desired. The gas is compressed into them at the compression stroke and expands back into the cylinder on the return stroke, thus reducing the intake of additional gas and subsequently the compressor capacity. Additional flexibility is achieved using several steps of clearance control and combinations of clearance control and inlet valve control. Figure 4 shows the control characteristic of such a compressor.

Reciprocating compressors generate flow pulsations in the suction and discharge lines that have to be controlled to prevent over- and underloading of the compressors, to avoid vibration problems in the piping or other machinery at the station, and to provide a smooth flow of gas. Flow pulsations can be reduced greatly by properly sized pulsation bottles or pulsation dampeners in the suction and discharge lines.

Centrifugal Compressors

As with reciprocating compressors, the compressor output must be controlled to match the system demand. The operation may require constant flow despite changes in suction or discharge pressure. Compressor flow, pressure, or speed may have to be controlled. The type of control also depends on the compressor driver. Centrifugal compressors tend to have a rather flat head versus flow characteristic. This means that changes in pressure ratio have a significant effect on the actual flow through the machine.

Compressor control is usually accomplished by speed control, variable guide vanes, suction throttling, and recycling of gas. Only in rare cases are adjustable diffuser vanes used. To protect the compressor from surge, recycling is used. Controlling the flow through the compressor can be accomplished by varying the operating speed of the compressor. This is the preferred method of controlling centrifugal compressors. Two shaft gas turbines and variable speed electric motors allow for speed variations over a wide range (usually from 50 to 100 % of maximum speed or more).

Virtually any centrifugal compressor installed since the early 1990s in pipeline service is driven by variable speed drivers, usually a two-shaft gas turbine. Older installations and installations in other than pipeline services sometimes use single shaft gas turbines (which allow a speed variation from about 90 to 100 % speed) and constant speed electric motors. In these installation, suction throttling or variable inlet guide vanes are used to provide means of control.

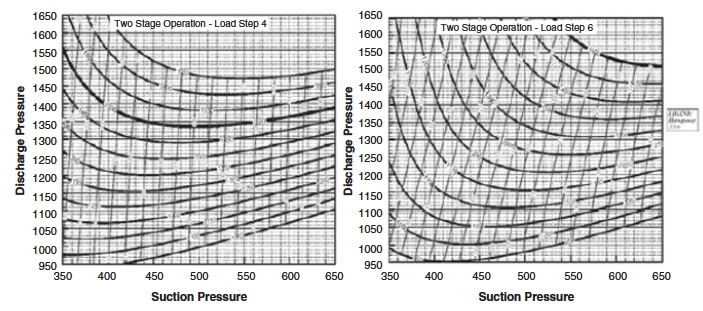

The operating envelope of a centrifugal compressor is limited by the maximum allowable speed, the minimum allowable speed, the minimum flow (surge flow), and the maximum flow (choke or stonewall) (Figure 5).

Another limiting factor may be the available driver power. Only the minimum flow requires special attention because it is defined by an aerodynamic stability limit of the compressor. Crossing this limit to lower flows will cause pulsating intermittent flow reversals in the compressor (surge), which eventually can damage the compressor. Modern control systems can detect this situation and shut the machine down or prevent it entirely by automatically opening a recycle valve. For this reason, virtually all modern compressor installations use a recycle line (Figure 6) with a control valve that allows the flow to increase through the compressor if it comes near the stability limit. Modern control systems constantly monitor the operating point of the compressor in relation to its surge line and automatically open or close the recycle valve if necessary.

The control system is designed to compare the measured operating point of the compressor with the position of the surge line (Figure 5). To that end, flow, suction pressure, discharge pressure, and suction temperature, as well as compressor speed, have to be measured.

Compressor Performance Maps

Reciprocating Compressors

Figure 7 shows some typical performance maps for reciprocating compressors.

Because the operating limitations of a reciprocating compressor are often defined by mechanical limits (especially maximum rod load) and because the pressure ratio of the machine is very insensitive to changes in suction conditions and gas composition, we usually find maps depicting suction and discharge pressures and actual flow. Maps account for the effect of opening or closing pockets and for variations in speed.

Centrifugal Compressors

For a centrifugal compressor, the head (rather than the pressure ratio) is rather invariant with the change in suction conditions and gas composition. As with the reciprocating compressor, the flow that determines the operating point is the actual flow as opposed to mass flow or standard flow.

Head versus actual flow maps (Figure 5) are therefore the most usual way to describe the operating range of a centrifugal compressor.

It will be interesting: Phase Separation: An Essential Process in Hydrocarbon Production

These maps change very little even if the inlet conditions or the gas composition changes. They depict the effect of changing the operating speed and define the operating limits of the compressor, such as surge limit, maximum and minimum speed, and maximum flow at choke conditions. Every set of operating conditions, given as suction pressure, discharge pressure, suction temperature, flow, and gas composition, can be converted into isentropic head and actual flow using the relationships described previously. Once the operating point is located on a head flow map, the efficiency of the compressor, and the required operating speed, as well as the surge margin, can be determined.