Effective management of Gas Plant Assets requires a transition from traditional isolated operations to a highly integrated performance model. As energy costs rise and market volatility demands greater operational agility, the ability to sustain high plant availability and utilization becomes a critical competitive advantage. This study examines how modern facilities achieve superior returns not merely through technology, but by aligning organizational behavior with sophisticated information strategies. By addressing the “operations wall” – the gap between strategic scheduling and tactical execution – operators can transform raw data into actionable knowledge.

- Introduction

- The Performance Strategy: Integrated Gas Plant

- Strategies for Organizational Behavior and Information

- Organizational Behavior Model

- Information Quality

- Perception of Information

- Capability to Perform

- Organizational Hierarchy of Needs

- Behavior

- The Successful Information Strategy

- The Impact of Living with Information Technology

- Vision of the Modern Plant Operation

- Operations strategy

- Model Based Asset Managment

- Optimization

- Tools for Optimization

- Optimization Alternatives

- Industrial Relevance

- The Technology Integration Challenge

- Scientific Approach

- Other Miscellaneous Initiatives

- Conclusion

This discussion explores a vision for the modern integrated plant, where model-based asset management and scientific optimization provide the foundation for stability. Central to this approach is the recognition that technical risks and business performance are inextricably linked. Through a multidisciplined assessment of information quality, perception, and organizational readiness, the following sections outline a framework for navigating industrial disturbances. This perspective shifts the focus from simple containment to a state of operational agility, ensuring that capital investments in digital infrastructure yield measurable improvements in safety, reliability, and long-term profitability.

Introduction

Maximizing the return on gas plant assets becomes increasingly difficult because of the rising cost of energy in some cases and the increased demand for operations agility in most cases. On top of these demands, there is the constant need to increase the availability and utilization of these plants. It is worthwhile to consider techniques and the profit improvement of some of the world’s best gas plants. This analysis identifies some key manufacturing and business strategies that appear to be necessary and are feasible for many facilities to achieve and sustain satisfactory performance. The essential nature of operating a gas plant is dealing with change. Disturbances such as slugging, trips of gathering compressors, weather changes, and changes in market demands make it challenging to operate reliably let alone profitably. A stabilization strategy is necessary but insufficient for most gas plants; it is necessary to sustain a degree of flexibility. A useful objective can be tracking desired changes and withstanding undesired changes in a manner that is safe, environmentally sound, and profitable.

The main challenges to gas plant profitability are as follows.

- Continuous energy and yield inefficiency due to providing operating margin for upsets and plant swings.

- Continuous energy and yield inefficiency due to not operating at optimum conditions.

- Energy and yield inefficiency due to consumption during plant swings.

- Labor costs to operate and support a gas plant – a poorer performing plant requires more personnel with a higher average salary.

- Plant integrity.

- Process and equipment reliability.

- Poor yield due to low availability.

- Maintenance.

- Safety.

Poorer performance compounds the cost challenges in most gas plants. To ensure that these problems are avoided, it is essential to develop a fundamental understanding of all the technical factors impacting the performance of the plant, how they interact, and how they manifest themselves in business performance. This can only be achieved through the application of an integrated approach utilizing the diverse skills of a multidisciplined team of engineers combined with the application of a robust performance-modeling tool. Technical assessments allow an understanding of technical risks to which the facility is exposed, ranging from deterioration of equipment due to exposure to corrosive environments to poor process efficiency as a result of poor design. Integration of expertise within a single team, which covers the broad range of technical fields involved in the operation of the gas processing plant, ensures that all the technical risks and interactions are identified.

Other business questions that asset managers are asking themselves:

- Are the assets performing to plan, and how do we know?

- Are we choosing the optimal plans for developing the assets over their lifetime?

- Are we achieving the targeted return on capital employed for the assets?

- Are we meeting all of the ever-growing health, safety, and environment guidelines?

- Can we forecast reliably, allocate with confidence, or optimize with knowledge?

- Do we derive enough value from the simulation and engineering model investments?

- How effective is the organization at capital avoidance?

- Are we drowning in data or are we knee deep in knowledge?

Another area of opportunity is optimization of the process to maximize capacity or yields and minimize energy consumption while maintaining product qualities. Many tools have become available in the past decade as powerful, inexpensive computing power has become available to run complex software quickly and reliably.

This chapter describes a vision of the integrated gas plant of the future and methods to identify solutions for attaining operational goals to maximize asset values.

The Performance Strategy: Integrated Gas Plant

Successful gas plants have found that a combination of techniques is necessary.

- A strategy to influence organizational behavior.

- A strategy to integrate information.

- An operations strategy that uses remote operations and support of unmanned plants.

- Process performance monitoring.

- Asset management.

- Process optimization implementation.

Merely adding technology without developing a new organizational behavior and operations strategy has often reduced gas plant performance instead of improving it.

The revolution in digital technologies could well transform the industry. Achieving the vision of the integrated gas plant of the future will require more than new technologies alone. It will require the alignment of strategy structure, culture, systems, business processes, and, perhaps most important, the behaviors of people. Visionary companies who truly want to capture the “digital value” will need to create a climate for change and then maintain strong leadership through the change and employ the skills and techniques from vendors to provide the technologies.

Read also: Plant Operation and Maintenance of Hydrocarbon Containing Equipment and Processes

Gas plant operators are looking to integrate global operations and the energy supply chain into a cohesive picture. A global enterprise resource planning system gives companies the resources they need to better balance supply with demand, reduce inefficiencies and redundancies, and lower the total cost of information technology infrastructures. The challenge is to develop overlay solutions with more domain content that can improve the knowledge inside the enterprise systems that producers depend on most for operations, planning, project management, workflow, document management, executive information and decision support, scheduling, database management, data warehousing, and much more.

The industry must capitalize on the opportunities provided by ever more capable and cost-effective digital technology.

Strategies for Organizational Behavior and Information

Understanding and managing organizational behavior are important elements of effective operations. The effective management and coupling of technology to people are crucial elements in ensuring that the plant’s culture will change to support modern manufacturing strategies.

Four typical organizational cultures have been observed. These cultures vary from cultures very resistant to change to cultures that change for the sake of change.

Organizational Behavior Model

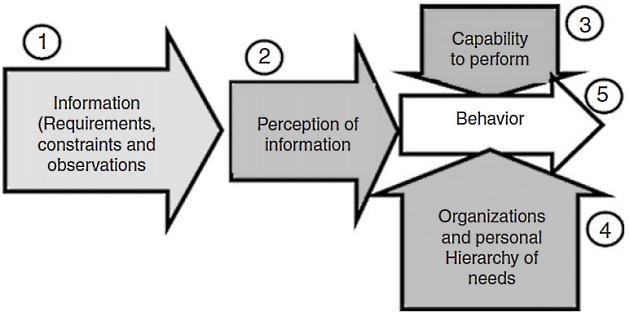

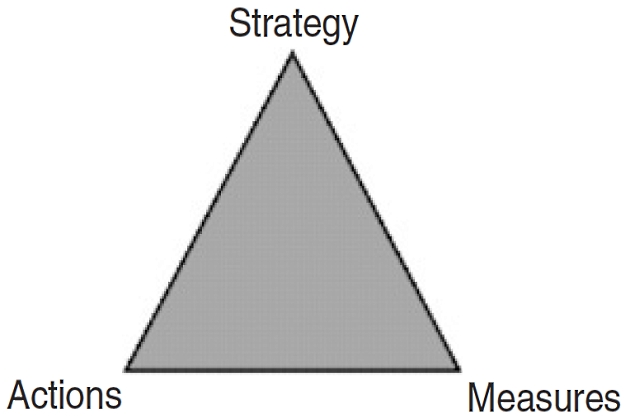

It is worthwhile to review recent modeling attempts for organizational behavior. Two models, each focusing on different aspects of the organization, deserve exploration. Both attempt to explain the influence of information and management activities on organizational behavior. The first model, as shown in Figure 1, attempts to identify and provide a structure for the various major influences on the organization.

This model supports the following observations.

- Unless constrained by their situation, people will improve their behavior if they have better information on which to act.

- Behavior is constrained by their capability to perform. This constraint is tied to the span of their control, their associated physical assets, and what the military calls “readiness“.

- The classical personal hierarchy of needs, which includes “survival“, “hunger“, and “need to belong“, applies to organizations as well.

Information Quality

The Natural Gas Processing and Liquids Recoverynatural gas processing industry is unusual in its high degree of dependence on information technology in order to meet its business goals. With the enormous quantities of data that it generates and processes, an edge is gained by ensuring the quality of data and using the information intelligently. In addition to this problem, the industry is addressing the changes required due to new and evolving working practices that the popularity of interdisciplinary asset teams has brought about.

This organizational model explains in part why people and organizations behave in a rebellious manner, despite receiving “better” information. For example, operators and their supervisors are penalized for “tripping” units and major equipment; however e-business decisions might require them to operate the plant in a manner that would increase the likelihood of trips. Another example is where a plant or unit’s performance is broadcast to a team of marketing and other plants, while the plant or unit is chronically “under performing” based on the other organizations’ expectations.

This motivates the plant’s managers to hide information and resist plans for performance improvement.

This model also points to a key issue in managing technology. Poor-quality information will be discarded, and information that is harder to use will not be used. This points to the need to define the quality of information. Suggested attributes of information quality include the foloowing.

- Available (is the information chain broken?).

- Timely.

- In the right context.

- Accurate.

- To the right place.

- Easy to understand.

It may be helpful to imagine a fuel gauge in the dashboard of a car. If the fuel gauge is working 75 % of the time, the driver will not trust it – the gauge will be ignored. In process plants, information has to be much more reliable than that to be trusted.

Gas plants struggle to convert supply chain schedules into actual plans. Too often, the marketing department does not have appropriate feedback that equipment has failed or that a current swing in recovery mode is taking longer than expected to complete. Conversely, the operations department often lacks the tools to plan which resources and lineups to use, while avoiding poor utilization of equipment. This gap between strategic and tactical scheduling is sometimes referred to as the “operations wall“. Much attention is given to networking information and knowledge software. So much attention is given to making as many components as possible accessible via the Web to support virtual private networks and restructuring knowledge software using application service providers.

This work is worthwhile, but the underlying information reliability issues are chronic and damage the credibility of major network and software installations.

The old expression “if garbage goes into the computer, then garbage will come out” is especially true for modern information technology strategies that end up with more than seven layers of components that process information. It is extremely important to note the following.

- Much of the information used to enhance and change plant performance, as well as support supply chain management decisions, is based on sensors that degrade in accuracy and “fail” due to stresses or material that reduces their ability to produce a reliable measurement. A modern hydrocarbon processing plant uses hundreds of these to support advanced control and advanced information software. Simply connecting digital networks to these sensors does not improve information reliability if the sensors do not have enough “intelligence” to detect and possibly compensate for failure or inability to measure.

- Most components and software packages process online diagnostic information that gives some indication of the reliability of the information. However, most installations do not integrate these diagnostics with the calculations. If the information reliability of each of seven components from the sensor to the top e-business software is 95 %, then on average the overall information reliability is no better than 69 %. Raising the component reliability to 99 % still only yields a maximum overall information reliability of 93 %, which is unacceptable for supply chain management.

Therefore, it is important to use as much “intelligence” as possible at all levels and to maintain the integration of online quality statuses to maximize the quality and minimize the time to repair the failures.

Perception of Information

Tables of menus and numbers do not help when a downsized team is asked to open multiple applications and “mine” for information. Most information displays are essentially number tables or bar graphs superimposed on plant flowsheets. Several plant examples exist to show how this interferes with improved performance.

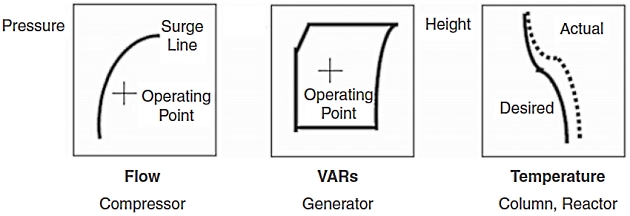

Two-Dimensional Curves and Plots

As an example, compressors can be the main constraining factor in major hydrocarbon processing facilities, and it is important to maintain the flow sufficiently high through each stage of compression to avoid surge. Too low a pressure increase is inefficient and limits production throughput. The most efficient is at higher pressure increases, but yields operation closer to surge. Operators are normally given a pair of numbers or bar graphs for pressure and flow, and they need to recall from experience where the “operating point” is compared to the “surge line“. To make matters worse, the “surge line” changes position as the characteristics of the gas change. To solve this, plot the moving surge line and the operating point in real time. This is a suitable solution for distillation and reactor temperature profiles as well (Figure 2).

Prediction Trends

The same operators who avoid trips tend to shut off advanced control software when the software is driving the plant toward undesirable states.

However, often the software is only using a spike to accelerate the transition to best performance, and the top of the spike still keeps the plant in the desirable state. Prediction trends allow operators to see the remainder of the curve so that if the curve looks safe, they will allow the software to continue with the spike.

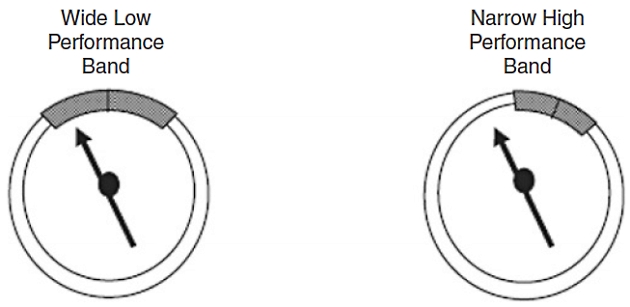

Dynamic Performance Measures

Operators and their supervisors are given performance information and targets, but often the information is not “actionable“, i. e. they cannot influence the information directly (Figure 3). Furthermore, as manufacturing strategies change, they receive e-mails with a set of numbers.

Ideally, the senior operators and their chain of management are seeing the targets and acceptable bands along with each actionable performance measure. In this way, coordination of a change in a manufacturing tactic is faster and easier. A common example is changing from maximum throughput (at the expense of efficiency) to maximum efficiency (at the expense of throughout) to take advantage of market opportunities and minimize costs when the demand is reduced.

Performance Messages

Operators who monitor long batches, especially batches that cover a shift change, tend to have lower productivity, especially during times that the main support staff is not available. Ingredients that exhibit quality problems can be used in applications such as in-line blending of fuels and batch blending with on-line analyzers to support a performance model with a set of messages and procedures that allow operators to modify the batch during the run and avoid a rework.

Capability to Perform

When the organization can perceive their performance and the distance away from targets, more accurately, they can develop a culture of learning how to improve. This is different than monthly accounting reports that show shadow costs and prices. This requires a condensed set of reliable information that supports factors that they can change. Examples include reliability, yield, quality, and throughput, and often it might be expressed in a different way. For example, reliability may be more “actionable” when expressed as “cycle time“, “turnaround time“, etc. Cutting the setup time from an overall 5 to 2,5 % is actually cutting the time by 50 %; this is far more vivid than showing availability changing from 95 to 97,5 %.

It will be interesting: Offshore terminal for transshipment of liquefied gas

Research has been conducted on complex operations where a unit is several steps away from the true customer, and attempts to establish internal costs and prices of feedstock, utilities, and internal products have had insufficient credibility or even ability to affect a change. Some attempts at activity-based costing have tried to increase the percentage of direct costs, with the result that the cost per unit of product is so weighted with costs outside of the unit that the unit manager cannot affect a useful improvement or is motivated to maximize throughput. Maximizing throughput is the only degree of freedom because the “costs” are relatively fixed. This is incompatible with modern manufacturing strategies that require precise, timely changes in prioritization of throughput, efficiency, and specific formulations to attract and retain key customers and more lucrative long-term contracts.

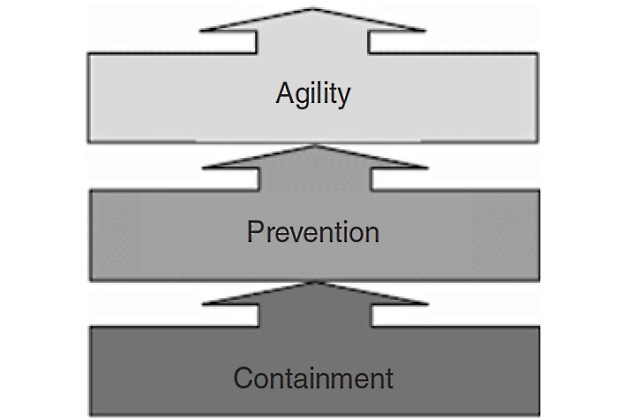

A key element of an organization’s capability to perform is its ability to handle both planned and unplanned disturbances. Modern manufacturing strategies become a nightmare if the organization and facilities cannot cope with the accelerated pace of change brought on by the tight coupling with suppliers and customers. The following model, as shown in Figure 4, helps describe different levels of readiness.

Containment is the lowest level of readiness, and at this level, unplanned disturbances stop production or cause product rework, but the damage is “contained” – no injury, equipment damage, or environmental release. Unplanned disturbances include operator errors, equipment failures, and deviations in feedstock quality as well as other factors. This level of readiness can be achieved with conventional information strategies.

- Loose or no integration between components, from sensors to supply chain software.

- Minimal integration of diagnostics of information quality.

- Minimal performance information.

- Minimal coordination between units or assets to withstand disturbances.

- Reactive or scheduled maintenance strategies.

Prevention is a level of readiness where unplanned disturbances rarely affect production availability or product quality. However, this operation cannot consistently support planned disturbances to production rates, feedstock quality, or changes in yield or product mix. It is usually a case of stabilizing the plant as much as possible in order to achieve this level of performance. This level of readiness requires more advanced information strategies.

- Moderate integration between components and a reliable connection to supply chain software.

- Good management of information quality.

- Good coordination between units and assets.

- Scheduled maintenance at all levels.

- Better performance information.

Agility is a level of readiness where the plant can consistently support wider and faster changes in feedstock quality, production rates, and output mix without reducing production availability or quality. This operation consistently achieves “prevention” readiness so that it can outperform other plants because of its agility. This level of readiness requires the most advanced information strategies.

- The tightest integration of all levels of software and sensors.

- Good models that drive performance information and online operations advice.

- A reliability-centered maintenance strategy for information technology.

- Good coordination with knowledge workers, who will likely come from key suppliers of catalysts, process licensors, information and automation technologies, and workers at other sites of the company.

There is a tendency in many operations to try to jump from “containment” to an “agility” level of readiness by adding more information technology, but with the characteristics of “containment” (minimal integration, etc.). This is potentially disastrous. Supporting modern manufacturing strategies can mean that the quality of integration is as important or more important than the quality of the information components themselves.

Due to the complexity of the interactions between technical factors affecting asset performance and the difficulty in converting technical understanding into a business context, the traditional approach has been to try and simplify the problem. Application of benchmarking, debottlenecking studies, maintenance, and integrity criticality reviews have all been applied to enhance process plant performance.

Each of these approaches tends to focus on a particular element of an assets operation. As a result, enhancement decisions are made without a full understanding of the impact on the assets performance and the overall business impact. This can result in opportunities being missed, capital being poorly invested, and delivery of short-term benefits, which are unsustainable. In the worst cases, this can result in a net reduction in plant performance and increased life cycle costs.

Organizational Hierarchy of Needs

Attempts to evolve plant culture by transplanting methods and equipment have not only failed but actually eroded performance. Key observations include the following.

- Personnel may not associate performance or knowledge with increased security, wealth, and sense of belonging or esteem. They observe promotion and compensation practices and evaluate the effectiveness of improving their situation against new expectations for better performance.

- Risk-adverse cultures dread the concept of visual management, benchmarking, or any other strategy that is designed to help a broader teamwork together to continually improve performance. Information that shows performance can be used to support rivalries rather than inspire teams to improve.

- Organizations and personnel worry about surviving – will the plant be shut down? Will the staffing be reduced? Efforts to change behavior using information have to be coupled to the hierarchy of needs and then the information can evolve as the organization evolves (and performance improves).

Research on dynamic performance measures has uncovered an effective model of organizational behavior that is especially appropriate for manufacturing. Two of the key issues that have been addressed are overcoming over 85 years of traditional organization structure that tries to isolate units and departments and the 20 years of cost and performance accounting.

The challenges with cost accounting are assigning costs in the correct manner. A plant manager or operations manager might face an insurmountable fixed cost. This motivates him/her to maximize production, which might be opposite to the current manufacturing requirements.

Read also: Common Hazards and Risk Assessment in Oil and Gas Industry

The poor credibility of internal prices for utilities, feedstocks, and products also has motivated middle management to drive performance in the wrong way. These point to the need to redefine key performance indicators (KPIs). The group of research efforts to deal with this is called dynamic performance measures. The US Department of Labor and many large corporations embrace dynamic performance measures.

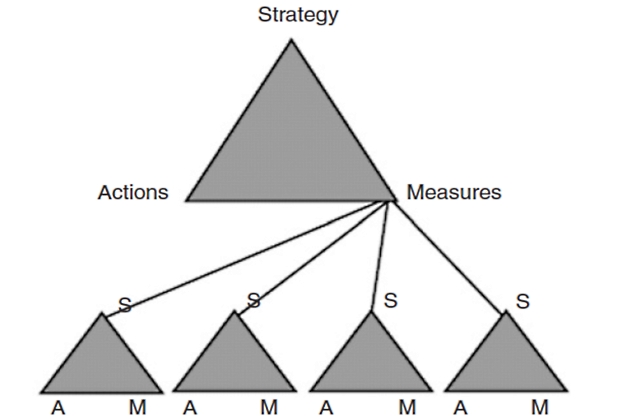

Vollman et al. have developed a model that associates the manager’s strategy and actions to their measures of performance. This combination is called the Vollman triangle, as shown in Figure 5.

The manager’s subordinates will develop their own triangles to support their supervisor’s measures, within the constraints of their capability to perform and so on as outlined in Figure 6. This occurs at all levels of the organization. The goal is to ensure that a small group of measures (no more than 4), which can be consistently affected by that level of operations, are maintained with suitable quality. If this structure is maintained, then it is easier for top management and modern manufacturing strategies to affect change.

The “actionable” measures tend to conflict with each other. Higher throughput or quality often comes at the expense of efficiency, or each has a different optimum. Each person learns how these interact. Discussions on performance improvement become more effective because personnel can now describe this behavior. The discussion is vastly different than reviewing monthly reports. As far as operations are concerned, something that occurred several days or weeks ago is ancient history.

Behavior

The most important variables for performance are work culture, job security, and career mobility. In many parts of the world, knowledge, experience, or skill is not sufficient to achieve promotion. Many cultures do not embrace an openness of sharing performance information, visual management techniques, etc. Therefore the information strategy needs to by adjusted to reflect the current human resources strategy and ideally both will evolve in phases to achieve world-class performance.

Another strong issue is traditions at the plant. It is often much easier to initiate new teamwork and performance initiatives to a new plant with a new organization. Nevertheless, the right information strategy becomes a catalyst of change. Everyone can see the performance against the current targets, and everyone can understand the faster change of priorities, such as changing from maximum production to minimum, where maximum efficiency is desired.

The Successful Information Strategy

Technology makes it easier to measure variables such as pressure, speed, weight, and flow. However, many operations achieve profitability with very complex equipment, and the key characteristics are properties, not basic measurements. A notable example is found in oil refining. The basic manufacturing strategy is to improve yield by converting less valuable components from crude oil (molecules that are too short or too long) into valuable components (medium-length molecules). However, the essential measurement to determine the proportion of different molecules is chronically unreliable. New technology now exists to reliably indicate a property called “carbon aromaticity“, which helps the operations team ensure that the process will be effective and that the feedstock will not degrade the expensive catalyst materials and erode production.

Reliable property measurement is the key. This also helps to evolve the plant culture from thinking about pressures and flows to thinking about properties. The information strategy becomes the following.

- Assess the organization’s readiness to support the desired manufacturing strategy and use of information to evolve the plant culture.

- Depending on the organization’s hierarchy of needs, develop a phased evolution of the information strategy.

- Develop appropriate measures that will directly support the actions needed to implement the strategy at all levels.

- Develop the appropriate information to maximize its quality, reliability, and perception.

- Manage the quality and reliability of information.

Data integration and visualization will continue to be a key area of focus throughout the next few years in digitizing the asset. Many new applications will bring knowledge gleaning ability from the data collected.

The Impact of Living with Information Technology

If the organization invests in “intelligent” components that enable advanced maintenance strategies, such as reliability-centered maintenance or performance monitoring centers, then the organization is committing to the advanced strategy. Otherwise the flood of extra information will be disruptive. Intelligent sensors deliver up to 10 times as much information as conventional ones; a typical down-sized organization, with as little as one-fifth the staffing of 10 years ago, would have to deal with 50 times the volume of information – too much. The information is only useful if it is coupled with appropriate software and methods to use the information to optimize the maintenance and maximize overall information and plant availability.

It will be interesting: Liquefied Natural Gas Commercial Considerations

If the organization invests in supply chain management technology, then the organization is committing to an “agility” level of operations readiness and a team-based performance culture. The organization is also committing to business measurement changes – cost per unit of product gets in the way of profitability measures of reducing procurement costs or increasing return on sales using modern manufacturing strategies.

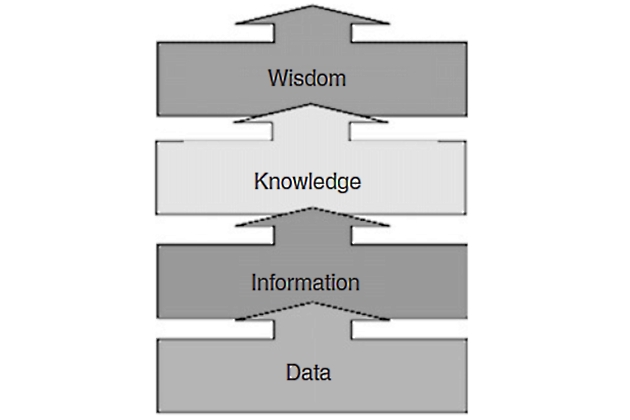

The organization develops a new language and starts to use new terminology. Furthermore, managers start focusing on managing the higher levels of information. The following model, as shown in Figure 7, suggests a new terminology for dealing with information.

This terminology can be defined as follows.

- Data: raw information from sensors and personnel keyboard entry.

- Information: validated data, using diagnostics and techniques to enhance the quality and reliability of information.

- Knowledge: a comparison of information to targets and constraints. This answers the set of “how are we doing?” questions.

- Wisdom: guidance for best practices, customer satisfaction, supply chain management, and any other performance guidelines.

Many organizations have managers spending much of their time dealing with the “Information” function rather than focusing on “knowledge” and “wisdom“. It is extremely important to maximize the quality and type of information to ensure that management can support the “agility” demands of modern manufacturing strategies.

Vision of the Modern Plant Operation

There are four different groups of activities that require consistent information for most effective operations.

- Operational decisions on an hourly or more frequent basis by operators, shift supervisors, or engineers.

- Tactical decisions on a 1- to 30-day basis by shift supervisors, engineers, purchasing, trading, and accounting.

- Strategic decisions made on a 1-month to 5-year basis by plant management, purchasing and accounting.

- Monitoring on at least an hourly, weekly, and monthly basis by all parties involved.

Operational decisions include determination of set points for the equipment and switching equipment on or off. These decisions need to consider current pricing for commodities such as fuel and electricity, equipment availability, and environmental constraints. Furthermore, environmental constraints might be accumulative.

Tactical decisions include maintenance scheduling, demand forecasting, production planning, and emissions forecasting and trading. Strategic decisions require evaluation of future investment, budgeting, and longerm contract negotiations with suppliers and customers. Monitoring requirements include tracking plan versus target versus actual performance such as process energy use, cost accounting based on real costs, emissions accounting, and performance monitoring of utilities equipment.

Given that the quality and perception of information have to be improved in order to be used effectively to change an organization’s culture, there are five key issues highlighted by the aforementioned model that must be addressed.

- Capability to perform.

- Operations readiness.

- Organizational hierarchy of needs.

- Establishing “actionable” information to act as a catalyst of change.

- Measuring the right things.

Technology can be the most effective tool to evolve plant culture. The speed of distributing reliable, timely, and easy-to-use performance and supply information changes the level of discussion and the dynamic behavior of the organization. However, the organization needs to have the right set of performance measures, a persistent effort to enhance operations readiness, an appropriate human resources strategy, and, above all, appropriate quality of information. The impact of these on changing a plant culture can be dramatic – as soon as the team realizes the ability and need to improve, they learn quickly how to evolve their work methods to achieve it.

Modern manufacturing strategies are viable, and information technology strategies can transform the plant culture to achieve manufacturing success. The evidence of a change in the level of dialog and team dynamics confirms the success, but several key strategies must be maintained consistently in order to sustain this success.

Operations strategy

Major installations have been able to consolidate up to 10 control rooms and improve plant output by up to 15 %. The goal was not to reduce personnel – the goal was to improve flexibility because it is easier for a small team to drive change than a large one. This has been proven consistently in remote jungle sites in southeast Asia, remote mountain sites in the united states. and Canada, and remote sites in northern Africa.

There are several techniques necessary to make this feasible.

- Remote, secure, online computer access to all control and monitoring equipment.

- Advanced alarm management that dynamically filters alarms during upsets so that “alarm showers” are avoided that blur the visibility to key cause-and-effect alarms.

- Stabilization techniques to help units withstand upstream and downstream disturbances.

Model Based Asset Managment

Facility simulation has developed quickly over the last several decades. The integrated oil and gas field with production facilities is a complicated system with a high degree of interaction and dynamics that make it impossible for the human mind to control and optimize both technical and business parameters. Integrated discipline workflow and the development of model-based asset management are necessary to deal with these complexities effectively.

Model-based asset management techniques will begin to play a major role in the integrated Automation and Process Control of Liquefied Natural Gas Plants and Import Terminalsgas plant of the future in bringing the predictive power of the production engineering tool set to real-time data platforms. Process and production simulation models will move from the domain of the engineering expert to be used by managers, operators, business development, contracts, and finance. The analysis and prediction of near real time and future asset performance become a reality in the world of model-based asset management. For this the complete integrated asset will be modeled dynamically in real time for both slow rigorous and fast proxy loop modes.

Read also: List of the Emergency Situations which can happen on the Liquefied Gas Carrier

Facility simulation has come of age. The ability to predict very complex facility simulations in both steady state and dynamic mode has been achieved by continued integration of thermodynamic methods, hydraulic simulations, and unit operations. Facility simulation has progressed such that dynamic start-up and shutdown simulations have become routine and trusted among the engineering community. One can begin to think of dynamic simulation as a “virtual plant” for operational, advanced process control and business analysis by a number of different departments.

Facilities simulation, control, optimization, operator training, collaborative engineering and planning disciplines, have a rather fragmented application of a number of associated technologies. To overcome this fragmentation, the first step is the adoption of integrated asset models that use comprehensive existing applications that are integrated together by a common “glue” layer allowing a full model of the entire operation.

New concepts are appearing from the software community in the form of workflow solutions that enable assets to be modeled from a suite of selected software adaptors and can bring data from disperse and thirdparty tools into one common environment, creating the integrated asset model. One can then apply engineering and business applications to identify asset-wide improvement opportunities.

A portal environment can be built that will allow multiple asset models to be visualized, compared, and analyzed with distributed data sharing and events management via proven and accepted enterprise platform message bus technologies. Key visualization and workflow technologies required include look-forward analytics, production scorecard, workflow management, production reporting, capital planning and scheduling that can be performed on a uniform, company wide, basis and allow for rapid, informed decision making.

Optimization

Maximizing the profit contribution of Application of Dynamic Simulation in Gas Processing Facility Design and Operationnatural gas processing facilities is challenging given the fluctuating economics, changing ambient conditions, and feed variations that processors must address. New dynamic markets for gas components lead to a need for stronger analytical capabilities of decision support tools. Also the supply situation becomes more variable as the gas companies respond to market opportunities. The result is a more rapidly changing environment and, as a consequence, processing plants need to be reconfigured more often. There is a need for better understanding on how to make plant-wide production plans and implement these through process management.

Decision support tools have to combine both optimization and simulation capabilities in order to analyze the consequence of different scenarios. Advanced modeling and optimization are needed in order to address the new following challenges in plant control and optimization systems, which have an impact on the optimal design of Implementing Advanced Gas Processing Plant Controls for Optimizationgas processing plants.

- Many of the processing plants are short of capacity. It is more important than before to maximize flow through the plants or the profit from final products.

- New opportunities exist because of recent advances in modern control technology, e. g., model predictive control lifts the level of automation and gives better opportunities for process optimization systems at higher levels.

- Integration of tasks and systems in operation support centers. E-fields give a new perspective on operation of the oil and gas production, and this mode of operation must be prepared for in the gas processing plants.

- The man technology organization perspective, which provides relevant information for the personnel involved.

- The use of models for planning and process control plays a central role.

- Modeling the dynamics of the markets and incorporate it in contingent plans. The plans should reflect capacities and production possibilities of the plant. This again depends on the design and operation of the plant control system.

- Structuring of the information flow between layers and systems in the process in the process control hierarchy, real-time optimization level, and planning and scheduling levels.

- Self-regulating and robust systems, which optimize the other parameters.

- Limitations imposed by process design.

Tools for Optimization

Many of the tools mentioned in article “Implementing Advanced Gas Processing Plant Controls for OptimizationGas Processing Plant Controls and Automation” could become integral elements of the operations strategy for maximizing profitability. A steadystate process model is necessary to determine the capability and current performance of the operation. Ideally, a dynamic model would be available to train operators and investigate control options. These models can then be used in a real-time mode to report the capability of the plant under different conditions.

Predictive equipment models can be used to determine when maintenance will yield long-term benefits that more than offset the short-term costs. These models can be a extension of existing steady-state models. These steady-state models can also be key elements of an online optimization strategy.

Real-time control models can be constructed from perturbations of a high-fidelity dynamic model. It is necessary to validate these models constructed from models against actual plant data. Often the control models require detuning to provide adequate and robust control.

Optimization Alternatives

Some optimization alternatives for natural gas processing plants include the following.

- Advanced regulatory control.

- Multivariable predictive control.

- Neural network controllers.

- Off-line process simulators.

- Online sequential simulation.

- Online equation-based optimization.

- Linear programs.

- Web-based optimization.

Advanced regulatory control and multivariable predictive control are discussed in article “Implementing Advanced Gas Processing Plant Controls for OptimizationGas Processing Plant Controls and Automation“.

Neural network-based controllers are similar to multivariable controls except that they gather plant data from the DCS and use the data to “learn” the process. Neural network controllers are said to handle nonlinearities better than multivariable controllers and are less expensive to commission and maintain.

Neural network-based models are only valid within the range of data in which they were trained. Changes inside the process, such as a leaking JT valve, would be outside of the range in which the model was trained and therefore the results may be suspect.

Refining and chemical companies have attempted using neural networks for control many times since the mid-1990s. The technology has not proven to be viable compared to the other approaches, such as advanced regulatory control and multivariable control.

It will be interesting: LNG Panel Erection and Sealing Techniques

Off-line process simulators are used to develop a rigorous steady-state or dynamic model of the process. They are used by process engineering personnel to design and troubleshoot processes. Off-line simulations allow for what-if case studies to evaluate process enhancements and expansion opportunities.

Off-line simulators are typically not used to support daily operational decisions. They must be updated and calibrated to actual plant conditions for every use. They are not as robust as equation-based optimizers and can have difficulty converging large problems reliably and quickly.

A few of the off-line simulation companies offer an inexpensive, sequential-based optimization system. The optimizer is based on a rigorous steady-state model of the process and is typically less expensive than equation-based systems. They leverage the work done to develop the off-line model for online purposes. The extended convergence times inherent in these systems bring into question the robustness of the technology.

The sequential nature of the solving technology also can limit the scope of the system. These systems require hardware and software to be purchased, installed, commissioned, and maintained onsite and require specialized resources to support them.

Equation-based optimizers use a rigorous steady-state model of the process as the basis for optimization and include an automatic calibration of the model with each optimization run. The equation-based solving technology allows optimizers to execute quickly and robustly, making them viable for larger-scale problems, i. e., multiplant load optimization for plants on a common gathering system.

Equation-based optimizers require a hardware platform, a costly software component, and highly specialized The Essential Role of Power Supplies in Electrical Engineering on the Shipengineering services to install, commission, and maintain the technology. Closed loop implementation requires a multivariable controller to be installed to effectively achieve the optimal targets.

On-line equation based optimizers, when coupled with a multivariable controller, represent the standard in optimization technology for refining and petrochemical industries. Most refiners and petrochemical companies are deploying this technology rapidly to improve the profit contribution of their larger scale processing facilities. Unfortunately for gas processors, this technology is justifiable only for very large gas processing facilities and is not scalable across their asset base. Linear programs are used for evaluating feed and supply chain options. Linear programs are an off-line tool that allows for what-if case studies and evaluation of supply chain alternatives. They are relatively inexpensive. Linear programs provide a linear representation of the plant process and do not provide guidance for operators.

Web-based optimization has been applied to cost effectively supply equation-based optimization to the natural gas processing industry. However, the time lag in collecting data, calculating the optimum, and providing advice to the operators to implement the advice may not be fast enough to keep up with the constantly changing conditions experienced in natural gas processing plants.

Another option is on-line performance monitoring tools that predict the optimum operating point under all conditions. These tools usually provide dashboards and graphical indicators to show the operator the gap between current plant performance and optimum performance. They may or may not provide advice on what parameters to change to reach optimum performance.

Industrial Relevance

In the upcoming decade there will be large investments in gas production and in facilities for transportation and processing. Optimal utilization of all these facilities is vital in order to maximize the value from produced natural gas. Advanced process control and operation have raised the level of automation in the process industry significantly in the last decades.

For example, in the refinery industry, methods such as model-based predictive control (MPC) and real-time optimization (RTO) have become widely used. The focus on these technologies has given large benefits to the industry in the form of increased throughput and more robust operation. The improvements obtained by the use of better control and decision support tools ends up directly on the bottom line for the operating companies. The substance of these tools is in fact software realization of process knowledge, control, and optimization methods.

MPC and RTO are now more or less off the shelf products, although for complex processes the adoption of this technology requires specialist competence. However, there are significant potentials for further improvements in this area. One challenge for the gas processing plants is being able to quickly adapt the plant operation to dynamic changes in the markets, thus the plant flexibility and ability to perform rapid production changes becomes more important. It is also required to know accurately the plant production capability, both on very short term (today-tomorrow) and on weekly, monthly, and even longer horizons.

This requires the use of advanced optimization tools and efficient process calculations. It is important to consider these issues related to dynamic operation also in the design of new processing plants and for modification projects. Investments in this type of project have typically a short payback time.

A combination of individual units into an integrated plant gives a large-scale control problem that is more than just the sum of the units. Cross-connections, bypasses, and recycling of streams give more flexibility, but at the same time, the operation becomes significantly more complicated, and it is almost impossible to utilize the full potential of a complex plant without computer-based decision support tools. Thus there is a need for the development of new decision support tools that combines optimization technology, realize process calculation models at a suitable level of speed and accuracy, and structure the information flow, both from the process measurements and deduced variables and from the support tool down to the manipulated variables in the control system. It is also needed to develop further the methodology related to plan-twide control in this context.

The Technology Integration Challenge

There are three likely scenarios of the deployment of the integrated gas plant.

- Business as usual. Digital technology, information, data, and models are used in an incremental way to reduce costs, increase recovery, and improve production, but no fundamental changes are made in business models, competitive strategies, or structural relationships.

- Visionary. Those who can best adopt and apply digital technologies, and concepts, will use them to gain significant competitive advantage. This will involve significant investment in software and information technologies along with culture and management change. The industry will need to demand leaders in the highly technical processes and modeling software contribute new and innovative solutions.

- Symbiotic relationships. Those who use the availability of turnkey solutions to optimize production and leverage into larger industry positions. This will involve the use of third-party technology consultants and solution partners in an unprecedented way.

For most companies, an evolution approach that blends all three scenarios may well be the chosen route.

The foundation of the integrated gas plant of the future is engineering simulation, with integrated asset models and portfolio views of the business built on top. At the heart of the digital revolution in the upstream energy industry is a shift from historic, calendar-based, serial processes to real-time, parallel processes for finding, developing, and producing oil and gas assets. Real-time data streams, combined with breakthrough soft-ware applications and ever-faster computers, are allowing the creation of dynamic, fast-feedback models. These dynamic models, running in conjunction with remote sensors, intelligent wells, and automated production and facility controls, will allow operators to visualize, like never before, what is happening in the facility and predict accurately what needs to happen next to maximize production and efficiently manage field development.

Scientific Approach

Optimal operation of gas processing plants is a challenging multidisciplinary task. Large-scale process optimization is challenging in itself. Thus, when we also consider dynamic conditions in the market and on the supply side the operation will most certainly run into problems that must be solved. Some will arise from the size of the problem, some from complex process behavior and from requirements to solution of complex optimization problems.

The starting point in this project is the need for decision support as seen from the personnel in a plant operating company. This defines a set of tasks that require optimization calculations, process calculations, and measurement data handling. The personnel in question can be plant operators, production planners, sales personnel, maintenance planners, process engineers, managements, etc. Experience from other applications such as gas transportation will be utilized.

The inclusion of market factors, capacity planning, and scheduling shall be focused, as this sets new requirements to vertical integration of process control and the optimization layers. We may, in fact, have several such layers, where, for example, the classical real-time optimization is just one element. In planning and capacity assessment, the RTO layer may be accessed by superior layers in order to compute the optimal process targets over a certain horizon.

Read also: Types, Layouts and Designs of the Liquefied Gas Carriers (LNG/LPG)

The requirements to process calculations for each type of task shall be classified. This may result in a set of optimization problems with different properties and requirements to solution approach and to the underlying process calculations and data handling, e. g., one approach from the planning side is to start with empty or extremely simple process models and to refine the models based on the requirements to the planning.

Segmentation into suitable process sections and control hierarchies are central issues. Here we can apply methods from plant-wide control in order to structure the control of the plant units in a way so that the influence from unknown disturbances and model uncertainties are minimized. A very important output in the first phase is to define high-level targets for the process control. The next important issue is to develop methods to select the variables that should be exchanged between the optimization and the process control layers. This is a control structure design task where the focus is on selecting the variables that are best suited for set point control in order to fulfill the process optimization targets in the presence of unknown disturbances and model parameters and measurement errors. Segmentation of the control into suitable sections and layers is also a part of this task.

Recent advances in process control technology also give a new perspective. For example, with an active MPC controller, information about active and inactive process constraints is high-level information that can be exchanged with the optimization layer instead of representing the constraint equations at the optimization layer.

Efficient use of models is such a wide area that this issue can be subject to extended research in separate programs. For example, in process design it is industrial practice to use quite detailed process models, including rigorous thermodynamics and representation of detailed phenomena within each process unit. In operator training simulators, detailed dynamic models are used, but these are rarely the same models as used in design, and the built-in process knowledge in the form of model configurations and parameters is usually not interchangeable because of different modeling approaches and different model data representation. The models used in MPC are normally captured from experiments on the process itself and are not connected to the other two types of models. For real-time optimization, steady-state models are normally used, and in some cases model tools with rigorous models are also used there. For capacity assessment, correct representation of potential bottlenecks is important.

Other Miscellaneous Initiatives

Maintenance management, field information handling, work process optimization, compensation design, and procurement initiatives are several of the current gas processing management initiatives.

In field information projects, companies considering an upgrade should understand that technical support must also be upgraded and that care should be taken to select systems with an eye toward ensuring the ongoing availability of support over a reasonable period.

In an effort to determine how they are doing against the competition, as well as discovering new areas for potential, some processors have become involved in industry benchmarking activities. Benchmarking tools with a reasonable level of analytical content provide benchmarking against a select peer group as well as individual analysis of various cost components. Most organizations that persevere in the benchmarking process and are diligent following up on findings testify that benchmarking is a useful tool.

A company that fully utilizes second-wave technologies to streamline its back office and process support technologies could reap a reduction in selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs in the range of 8 to 10 %. For a typical, large firm, SG&A costs represent an estimated 10 % of the total enterprise costs. Thus, a 10 % reduction in SG&A outlays would reduce overall corporate spending by 1 % a major gain, given that these savings would drop to the bottom line.

Conclusion

The goal of an integrated operations environment is to enable direct translation of management strategies into manufacturing performance. The vision is that:

- Utilization of raw materials is optimal.

- Overall margin and yield of product(s) are maximized.

- Planning, operational, and monitoring cycles are fully integrated.

- Identification and correction of problems occur rapidly.

- Operational (short and long term) factors are fully understood.

- The work force is well informed and aligned for a common purpose.

The system envisioned is an integrated platform for computing and information processing at the production level. It is built around the premise that information is not to be isolated and that better information, when made widely available, will help people operate the facility closer to the optimum. A key principle is to empower everyone to maximize the value of his activities. The production management system provides the tools to help personnel do their job better.

A fully functional system will enable the quality cycle of planning, measuring, analyzing, correcting, and then planning again. To make improvements the staff must be able to see and measure progress.

The integrated production/management system provides data and the means to analyze situations, define solutions, and track progress. It is an integrated platform of computers, networks, and applications. It brings together the many individual automated systems that exist today and fills any gaps to bring the overall system to a high level of performance.

The production/management system spans the gulf between process control and corporate business systems to support the day-to-day operations.

To achieve these goals, the production management system must:

- Be a single, comprehensive source of real-time and business data addressing all operations and available to all appropriate personnel. This means providing long-term storage of all data (e. g., historical process, laboratory, plan, production, and shipment data), merging of these data, and retrieving data.

- Provide information retrieval tools for the full range of users. This usually means highly graphical tools that provide ease of use and a consistent look and feel to minimize the burden of finding and accessing information.

- Integrate a wide range of computer systems and applications. No one system or set of tools will provide all the functionality needed. Instead, the production management system should allow for the use of the best products from different vendors.

- Provide standard screens and reports that focus attention on problems and opportunities. The system should report by exception, highlighting the unusual, the exceptions, and the opportunities. It should compare actual results with the established plans and economic KPIs.

- Maximize information content while minimizing data volume. This is achieved by the use of performance indices and other numerical, measurable indicators, and the presentation of this information in graphical form whenever possible.

- Present operational data in economic terms whenever possible. Opportunities, problems, and deviations from an operating plan should be prioritized based on their impact on overall profitability and, where possible, include an indication as to the action or follow-up activity that alleviates the deviation.

- Provide analytical tools that enable users to explore and pursue their own ideas. Much of the value of integrated operations comes not from presenting data about current operations, but from people looking for ways to improve current operations.

- Facilitate plant-wide communications and work flow. For instance, plans and economic KPIs set in the planning group should flow automatically to operations to help operate the plant. Beyond the manufacturing issues, implementing a project with the scale and complexity of an integrated production/management system creates several management of technology issues.

These create the need to:

- Balance the selection of individual applications with the need to integrate applications across departmental boundaries.

- Provide a single, accessible, look and feel. This is particularly important for users accessing data that originate in systems that belong to other departments (“single pane of glass”).

- Employ the latest proven information system technology as it becomes available and at the pace the operator can assimilate and manage.

Integration is a true example of the total being greater than the sum of the parts. A gas plant can profoundly affect the nature, quality, and profitability of its operations throughout the life of the gas plant with a truly integrated production management system.

It will be interesting: Basic Knowledge of Safe Working Practices and Procedures in Accordance with Legislation and Industry Guidelines Relevant to Liquefied Gas Tankers

Several operations have adopted some or all of the discussed strategies to improve their performance. A couple of these plants are discussed in Kennedy et al. Other examples include gas processing operations in Tunisia, Norway, Nigeria, and Indonesia.

The future seems to belong to those who will be able to mix vision, intelligence, and understanding of human nature, technology, and the processing business into a formula for success in the new world of natural gas gathering and processing!