This article provides a systematic overview of a Gas Plant Project lifecycle, focusing on standardized management processes and industry-specific execution strategies.

- Introduction

- Project Management Overview

- Industry Perspective

- The Project Management Process

- Defining Business and Project Objectives

- Contracting Strategy

- Conceptual Estimates and Schedules

- Project Execution Planning

- Pre Project Planning Measurement

- The Responsibility Matrix

- Project Controls

- Project Time Line

- Risk Management

- Quality Assurance

- Commissiomimg and Start-up

- Operate and Evaluate

- Project Closeout

- Conclusion

Successful implementation of such projects requires a rigorous approach to defining business objectives, selecting contracting strategies, and maintaining project controls.

Introduction

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities in order to meet or exceed stakeholder needs and expectations of a project. The project manager, sometimes referred to as the project coordinator or leader, coordinates project activities on a day-to-day basis. This is an ongoing challenge that requires an understanding of the broader contextual environment of the project and the ability to balance conflicting demands between:

- available resources and expectations (especially with respect to quality, time and cost);

- differing stakeholder priorities;

- identified needs and project scope;

- and quality and quantity of the project’s deliverables.

Project management for engineering and construction projects requires the application of principles and techniques of project management from the feasibility study through design and construction to completion. Good project management during the early stages of project development greatly influences the achievement of quality, cost, and schedule.

This chapter covers many aspects of managing capital projects in the gas processing business. For the most part, best-practice management for gas plant projects follows generic project management principles applicable to most industrial engineering and construction projects. This chapter reviews many of the standard and accepted practices that lead to successful installations, as well as some of the unique considerations for gas plant projects, which arise from relatively complex processes employed in typically remote locations.

Project Management Overview

One or more parties can perform the design and/or completion of a project. Regardless of the method that is used to handle a project, the management of a project generally follows these steps.

- Step 1: Project definition. Determine the conceptual configurations and components to meet the intended use.

- Step 2: Project scope. Identify the tasks that must be performed to fulfill the project definition. Also clarifies what the project does not include.

- Step 3: Project budgeting. Define the permissible budget plus contingencies to match the project definition and scope.

- Step 4: Project planning. Determine the strategy and tasks to accomplish the work.

- Step 5: Project scheduling. Formalizing the product of planning.

- Step 6: Project execution and tracking. Complete project tasks and measure work, time, and costs that are expended to ensure that the project is progressing as planned.

- Step 7: Project close-out. Final testing, inspection, and payment upon owner satisfaction.

Successful projects require effective management, which means:

- clear objectives,

- a good project plan,

- excellent communication,

- a controlled scope,

- and stakeholder support.

Project management in today’s organizations demands multiskilled persons who can handle and manage far more than their predecessors and requires competencies that span all of the critical management fields.

Industry Perspective

Gas plant project management includes planning, design, engineering, construction, and commissioning of the plant. Key elements are covered under the general headings of engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC). Today in many large organizations there has been a trend away from the owner company performing the whole project management function toward the delegation of EPC in part or whole to engineering consultant organizations. At the same time, smaller companies have almost always subcontracted EPC activities. Most companies, however, specify and procure the major equipment themselves (or at least oversee those activities) to assure technical compatibility and adequate lead times for delivery and so on. For example, the compressors and drivers will be specified and selected by the owner company as a priority.

A successful project in the gas processing industry is not only one that is profitable, but one that leads to the safe, reliable, predictable, stable, and environmentally friendly operational characteristics.

Gas processing is a service to the oil and gas production business. Oil and gas operations desire to produce into a system that has high availability and can produce a salable product in a safe, quality-consistent, and environmentally friendly manner. Gas processors must, of course, provide this service in a profitable manner. Flexibility to operate in various modes to respond to the markets and provide various processing alternatives should provide competitive advantages for a plant.

Read also: The Evolution of LNG Importer Cooperation – Partnerships, Safety, and Future Directions

In many cases, the gas processing facilities are owned by the oil and gas producers as first facilities to enable the production of oil and gas and then as a value-added operation. In some cases, particularly the present state of the business in the United States, independent gas processors compete for gas that can be produced into a number of gas gathering systems. Several types of contracts exist, but the prevalent contract type is a “percent of proceeds” arrangement. Processors, who can offer the greatest revenue to the oil and gas producers, have an advantage in any case. The key is recovery of the greatest percentage of feedstock at the highest availability and at the lowest cost.

The Project Management Process

At the onset of a project, the owner company will undertake the required economic and business analysis regarding new or expanded facilities in order to receive board approval and budget allocation. Based on this approval and funding, the project definition will be refined. The owner company will initiate the project and set out design objectives, usually embodied in the design basis memorandum (DBM), which will lay down the operating parameters and any key design guidelines and specifications.

The owner company will solicit bids from EPC contractors and from these will select the successful bidder. In some cases, owner companies will have a partnership with an EPC contractor for certain types and sizes of projects. Pricing will be prenegotiated according to a range of possible contract models (fixed price, cost-plus, risk-sharing, etc.) or performed on a reimbursable basis. Both parties, owner and contractor, will set up teams to do the work. The EPC company may be asked to be completely responsible for all aspects of engineering, procurement, and construction or may only be required to do engineering and some procurement with the construction carried out by another company.

Source: Unsplash.com

Estimates and schedules will be set up by the EPC company in consultation with the owner. EPC companies can be large, such as Bechtel, or small, such as Cimarron Engineering or Tartan in Calgary. Each company may have somewhat different expertise and experience but tend to operate in very similar ways. Consultants and contract personnel will fill areas where the EPC company lacks resources or expertise. The owner also embeds staff in the contractor to ensure oversight of the management process and also may include specialist engineering personnel to monitor progress against plan, including quality assurance, as well as training of the owner staff on major projects.

For more complex, large projects that involve elements of innovation or requirements to build a gas facility in a region or country where such projects have not been conducted previously it is not unusual for the process to include feasibility studies and front-end engineering and design (FEED) studies conducted prior to awarding the EPC contract. The feasibility and FEED studies usually conducted by competent engineering consulting companies, capable themselves of conducting the EPC work.

The deliverable from a FEED study may form the basis of a competitive tender for the EPC contract in which a number of prequalified contractors may compete.

A successful project requires the owner and EPC company to work together very closely. Typically, the owner will bring in operations staff at an early stage in the project to ensure that these staff members contribute to the project specifications and review deliverables as they unfold.

In this way commissioning and operation proceed without serious problems. Companies with experienced staff often prefer to have the operating people closely integrated with the construction work from the outset.

Similarly, with controls people, it is essential that the owner’s control philosophy is conveyed to the engineers of the contractor and that the machinery suppliers are brought into the loop so that engineering specifications and machine products reflect these perspectives. The owner company will undertake the required economic and business analysis regarding new or expanded facilities to receive board approval and budget allocation. From this the project will be defined.

Defining Business and Project Objectives

The first step in the project management process is to align the business and project objectives. A project can be installed on time and on budget, but if it does not meet the defined business objects, then the project cannot be deemed a success. Some of the questions that the business owners must be asked by the project team include the following.

- How much gas is available for processing (ultimate reserves and daily deliverable quantities)?

- What is the market demand for gas and gas products that can be met by this project?

- What is a realistic gas production schedule?

- What are the production pressure, temperature, and composition of the gas?

- How will the gas pressure, temperature, and composition change over time?

- What products can be sold and at what price?

- What are the product specifications?

- How will the products be delivered to market?

- What are the local environmental policies?

- What are the local safety policies?

- What infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, loading and unloading facilities, and personnel housing are required?

- What is the skill level of available operations and maintenance personnel?

Because most Implementing Advanced Gas Processing Plant Controls for Optimizationgas processing plants are services to the oil and gas producers, collaboration between reservoir and production engineers and gas marketers to obtain answers to these questions is imperative. In cases where processors compete, then collaboration with those responsible for obtaining the processing and sales contracts (e. g., economists, lawyers, and negotiators) can be critical.

The Project Charter

The project charter is a document that demonstrates management support for the project. In particular, it authorizes the project manager to lead the project and allocate resources as required. It simply states the name and purpose of the project, the project manager’s name, and a statement of support by management. Senior managers of the responsible organization and the partner organizations sign it. The project charter should be distributed widely to anyone with an interest in the project. This will help build momentum, encourage questions and concerns early in the project’s evolution, reinforce the project manager’s authority, and possibly draw other interested and valuable stakeholders into the project.

The project owner may be a joint venture of oil and The Resurgence of Liquefied Natural Gas in the Atlantic Basin and Qatargas companies, with one designated as project operator. The project charter is then usually signed off by all joint venture partners together with an authority for expenditure (AFE) approving the project budget and/or initial stages of expenditure.

Project Team Roles and Responsibilities

Project team size and makeup are dependent on the complexity of the project; however, the basic composition of the project team and their responsibilities is recommended for all projects.

- Project manager. The project manager is responsible for project development, developing schedule, budget, and deliverables definitions; evaluation of alternatives; determining return on investment; adherence to company policies; obtaining funding; acquiring internal and external project resources; contractor selection; maintaining project schedules and budgets; evaluating quality of project deliverables as they evolve; identifying and mitigating downside risks; identifying and exploiting upside opportunities; reporting to business owners; and creating project close-out reports.

- Business owner representative. The business owner representative is responsible for assuring that the project adheres to business objectives as objectives may change or require alteration during the project.

- Plant manager. A plant manager should be appointed as early as possible to address operability and maintainability issues.

- Project engineer/construction engineer/start-up engineer. A project/construction/start-up engineer can be one role on smaller projects and multiple roles in larger projects. This engineer (or engineers) is responsible for technical specifications for contract bidding purposes, technical evaluation of contractor bids, owner’s representative during construction, management of construction inspectors, turnover of facility to operations, training of operators, determination of plant performance, and identification of any project deficiencies.

- Purchasing representative. The purchasing representative is responsible for the commercial evaluation of contractor bids and negotiation of contract.

- Process engineer. A process engineer is recommended for evaluating alternative processing schemes during project development, assistance with technical specifications and evaluation of contractor bids, and assistance with operator training and start-up issues.

- Environmental engineer. An environmental engineer is recommended to review and provide advice on environmental issues encountered during the project, including technical specifications and obtaining environmental permits.

- Safety engineer. A safety engineer is recommended to review and advise on safety issues encountered during the project, including technical specifications and participating on hazard analysis evaluations.

- Production or reservoir engineer. A production or reservoir engineer is recommended to be available to evaluate any oil and gas production issues that may be encountered during the project.

- Facilities planner. For larger projects, a facilities planner should be available to assist with project economics and to serve as a liaison for economic premises and marketing issues.

Contracting Strategy

There are several alternative contracting stages and strategies. The first stage of contracting may be a front-end engineering design. With this approach, a contract is entered based on the design objectives for an engineering contractor to evaluate process and construction alternatives, as well as develop technical specifications for the project. In some cases, the owner’s engineers may accomplish the front end engineering design tasks. The second stage of contracting is for engineering, procurement, and construction services. Either stage can be contracted as a lump sum, fixed fee price also known as a turnkey project, or on a reimbursable basis also known as a time and expense contract. In some cases more complex contracts, such as risk sharing or gain sharing, will divide risks and rewards more evenly between contractors and project owners.

Conceptual Estimates and Schedules

Most operating companies have developed estimating tools for budgeting of plants similar to those they are currently operating. Many operating companies have the capabilities and resources to evaluate alternative pro- cess and mechanical designs with budgetary or conceptual level estimates.

These estimates typically have an accuracy of ±30-40 %. Under other circumstances, such as when proprietary processes are in use, unique locations are to be selected, or there is a lack of available resources, an engineering firm may be hired to evaluate alternatives and determine budgetary estimates. After evaluation and selection of a conceptual process and mechanical design, the operating or engineering company will undertake a front-end engineering design. The detailed specifications and request for proposals will be the deliverable from the front-end engineering design.

Conceptual estimates and schedules should take the following into consideration.

- Location.

- Operators and operability.

- Constructability.

- Special materials.

The availability of fresh water and electricity are considerations in determining location. Port facilities, roadways, and waterways are another consideration. A qualified and available work force is always a consideration when determining location. In some locations, qualified operating personnel are difficult to find so inexperienced and poorly educated operators may be hired. In order to overcome their lack of qualifications, intensive training is required. Generally, it is good to include in the project training using high-fidelity simulators, particularly where inexperienced operators are to be hired. In addition, plants with novel processes with which even experienced and highly educated operators are not familiar should include additional training provisions. Such training will impact the project’s cost and schedule.

Regardless of schedule, the project team’s capability to construct the facility must be addressed. For instance, vessels of large diameter and height will require shop facilities that have appropriate size capacity, as well as trucking and rail facilities that accommodate the finished products.

In some cases, the vessel may require field fabrication or multiple vessels will be needed if shop fabricated. Alternatives for prime mover drivers, such as electric motors, steam turbines, gas turbines, and gas engines, may be influenced by the availability of infrastructure to support these devices. If electrical service is not provided by a utility, then generation or cogeneration facilities may be required. These must be addressed in the project cost estimates and schedules.

Special materials are often required in gas processing plant construction due to components such as hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, mercury, and water. The availability of these materials and their delivery should be considered. Sometimes cladding or linings may be alternatives to expensive and scarce alloys. In addition, approved welding procedures may not be available or the work force may not have the expertise to perform certain procedures. Addressing such obstacles must be part of the project plans.

It will be interesting: Strategies for Effective LNG Bunkering Operations and Their Execution

During the proposal solicitation and award of the construction contract, the cost estimates and project schedule for the prime contractor will be focused on construction activities and therefore fairly detailed and inclusive. However, the overall project schedule from an operating company point of view must consider nonconstruction activities such as permits, licenses, and other government requirements, staffing, accounting, and other internal issues as well as contracts with suppliers and customers to name a few.

As project definition improves so the uncertainties associated with cost estimates should decrease to a funding level of accuracy of approximately +15 %/-10 % with a 10 % contingency identified. A probabilistic approach to cost estimating identifying percentiles (P90, P50, and P10) is also widely used to illustrate cost uncertainties.

Hazards and Operability (HAZOP) Analysis

A HAZOP analysis or equivalent is good practice even when not a statutory requirement. Such an analysis will most likely recommend the addition or deletion of valves, lines, instrumentation, and equipment needed for safe and reliable operation.

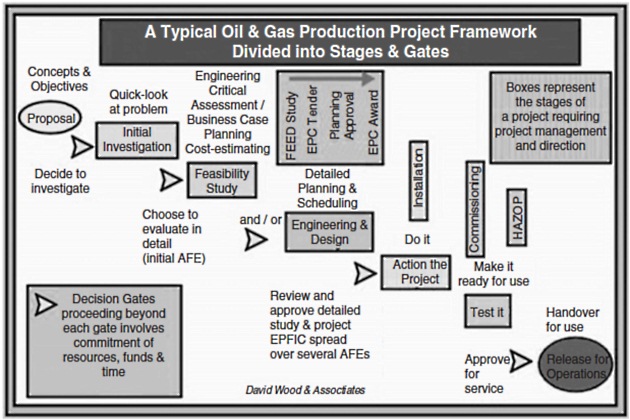

Figure 1 illustrates a stages and gates approach to oil and gas facilities project management that emphasizes the importance of the planning stages (feasibility, FEED) leading into EPC contracting, construction, and fabrication activity onto HAZOP and ultimately plant commissioning.

To move from one stage to another requires a gate to be passed where decisions and approvals have to be made associated with funding, technical design, and project priority. Such approvals are usually structured in the form of AFEs to be signed off by the project owners (and often other stakeholders, e. g., government authorities) as positive approval to proceed under stages of a project budget. Although the diagram for simplicity suggests a linear process proceeding from one stage to another, in practice there are often loops and feedbacks to the work of earlier stages that require adjustments to design and so on.

Scheduling and Cost Estimating Software

Software exists to assist with both conceptual cost and time estimates, as well as detailed estimates and complex project networks involving the optimization of project networks with critical path analysis. Most major engineering, procurement, and construction contractors have their own custom tools. Smaller contractors and operating companies may use products supplied by a vendor specializing in these tools. For larger projects, it is increasingly common for Monte Carlo simulation analysis to be used in conjunction with critical path identification to yield probabilistic estimates of cost and time associated with each project activity and for the project as a whole.

Project Execution Planning

A project must be planned and tracked against the plan to assure successful execution. A project plan sets the ground rules and states them in a clear fashion. The project plan helps control and measure progress and helps deal with any changes that may occur. Previous experience is the best guide for determining the necessary tasks and the time to complete them. Many engineering and operating companies maintain databases that include previous project plans with actual time to completion and costs.

To be able to benefit from such an approach requires good quality record keeping both during a project and following its completion. Although no two projects are identical no matter how similar they appear, these databases of past experience contain valuable information on which to plan. It is necessary to understand any unique requirements that previous projects met and how the current project compares. Some dissimilarities may include the following.

- location, which impacts the government regulatory bodies, remoteness, cost of labor, etc.;

- make-up of the project team, including expertise, time available, geographic dispersion of team members, cultural differences, organizational affiliations/loyalties;

- project scope;

- and current economic conditions, which affect inflation and employee availability.

The project plan should be relevant, understandable, and complete and reflect the size and complexity of the unique project. The project plan should include the following elements.

- A project charter.

- A project time line.

- A responsibility matrix.

- A project plan budget.

- Major milestones with target dates.

- A risk management strategy.

Pre Project Planning Measurement

The project objectives, or the measure for project success or failure, are often defined in terms of cost, schedule, and technical performance. In order to serve as a baseline for project execution, measurements should be in place to identify target completion dates, budgets, and expected technical performance. These measures should be included in a system that allows tracking of actual, target, and projected dates and costs with variances highlighted. The technical expectations should be tracked as well and checked for compliance as the project proceeds.

The Responsibility Matrix

Projects are a collaborative effort between a number of individuals and organizations working together toward a common goal. Managing a diverse team, often spread over several locations (and countries), can present some special challenges. A responsibility matrix is a valuable project management tool to help meet these challenges. The matrix ensures that someone accepts responsibility for each major project activity. It also encourages accountability. The responsibility matrix should correspond with the project time line. An example is shown in Table.

| Typical Responsibility Matrix a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Project team members | ||||

| Contractor | Owner/operator | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 | A | S | P | – | – |

| 2 | – | A | S | P | I |

| 3 | – | A | S | P | – |

| 4 | A | S | P | – | – |

| 5 | A | S | P | I | I |

| 6 | A | S | P | – | I |

| 7 | – | A | S | – | P |

| a S – sign off; A – accountable; P – primary responsible; I – input. | |||||

The left-hand column in Table lists all the required tasks for the project while the team members (e. g., project manager, project engineer, safety engineer, plant manager, purchasing agent) are listed across the top. A code is entered in each cell that represents that team member’s involvement in the task in that row. For example, choose codes appropriate to the project; the key is to clearly identify who has a role in every activity, who is accountable, and who must sign off. Make sure the matrix is included in the project plan so that every participant is clearly aware of his or her responsibilities.

Project Controls

The two main elements of a project plan are the time line and cost control. A time line assures that the project is scheduled properly to meet anticipated and promised dates. For projects that involve several parallel or overlapping activities, the time line becomes a network. Cost control assures that the project meets its budget.

Project Time Line

By dividing a project into the individual tasks required for completion, the project time line:

- Provides a detailed view of the project’s scope.

- Allows monitoring of what has been completed and what remains to be done.

- Allows tracking of labor, time, and costs for each task.

- Allows assigning of responsibility for specific tasks to team members.

- Allows team members to understand how they fit into the “big picture“.

This time line can take on a variety of formats and philosophies. The most prevalent philosophy is to determine the date for project completion and work backward to identify key dates when certain milestones require completion. In practice, the project completion date is first determined through iterations of what is possible going forward with contingencies and identifying an end date. This usually involves establishing a critical path of activities, which must be completed on time for a project not to fall behind its scheduled end date. If this end date is not acceptable, then acceleration plans should be explored. Most methods of acceleration require additional expense to accomplish objectives. These methods may include parallel tasking, overtime, and contractor bonuses for meeting an aggressive date to name a few.

Once the project milestones are set, then subtasks and assignments are identified. On large projects, certain tasks and subtasks will be assigned to an assistant project manager. The overall project manager will become responsible for coordinating the activities of the assistant project managers. The milestones, major tasks, subtasks are commonly shown in a Gantt chart. This type of presentation presents dependencies in a graphic display such as predecessors (tasks that must be completed prior to commencing the next task) and successors (tasks that cannot be started until a previous task is completed). Milestones are significant events in a project, usually the completion of a major deliverable or tied to vendor or contractor payments. A very good method to analyze subtasks is to consult with an expert on accomplishing the subject task, and the very best way is to receive an estimate with commitment from the person responsible for executing the task. This is where contractors and their bids contribute to the best task analysis possible.

Note that as the project progresses, there may be tasks that were not foreseeable in the original plan or tasks that are added to enhance the overall project outcome. The impact of additional tasks, delays, or even acceleration requires consideration of the impact on both the time schedule and resources. When changes to the schedule are warranted and feasible, the project manager should get a written agreement for the revised plan from all the key stakeholders in the project. A regular update of the time schedule is recommended as part of a routine project status report. The time period for such reporting may be weekly or monthly depending on the project or the stage of the project.

Risk Management

Risk is inherent in all projects. In project management terms, “risk” refers to an uncertain event or condition that has a cause and, that if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on a project’s objectives and a consequence on project cost, schedule, or quality. As discussed in previous sections, the measure for project success or failure is defined in terms of cost, schedule, and technical performance. Project risk management is intended to increase the likelihood of attaining these project objectives by providing a systematic approach for analyzing, controlling, and documenting identified threats and opportunities during both the planning and the execution of a project. The application of project risk management will vary from the operator (owner) or the contractor side. The term risk management is used to lump together different activities. These activities may be divided into the following.

- Activities related to the day-to-day identification, assessment, and control of uncertainties, i. e., risk management activities related to understanding and controlling the most important risks threatening the achievement of well-defined project objectives. This type of risk management may be based on a qualitative approach where each risk is assessed separately.

- Activities related to the periodic assessment of achieving project objectives, i. e., assessing the probability of achieving well-defined project objectives with respect to schedule, budget, or performance. The periodic assessment must use a quantitative approach based on the aggregation of most critical uncertainties.

- Activities related to the ranking of a set of alternative decision options/system solutions, i. e., ranking different alternatives with respect to their desirability measured in terms of the corresponding project objectives. Such ranking is typically performed at major decision gates during the conceptual design stage.

Risk management is a key to success for project execution, but is often constrained by inadequate work processes and tools. An overall understanding of the different Financing LNG Export Projects – Navigating Finance Risksrisk factors and how these affect the defined project performance goals is critical for successful project management and decision making. Project risk management is a systematic approach for analyzing and managing threats and opportunities associated with a specific project and will increase the likelihood of attaining project objectives. The usage of project risk management will also enhance the understanding of major risk drivers and how these affect the project objectives. Through this insight, the decision makers can develop suitable risk strategies and action plans to manage and mitigate potential project threats and exploit potential project opportunities. Project risk management is based on a number of different analysis techniques. The choice between these techniques is dependent on the quality of the information available and what kind of decisions project risk management should support. Day-to-day usage of project risk management is typically based on using risk matrices, accounting for both threats and opportunities. With sufficient uncertainty information, the project risk management analysis can be extended to provide more direct decision support through probabilistic cost-benefit analyses.

Application of Dynamic Simulation in Gas Processing Facility Design and OperationGas processing projects are often characterized by large investments, tight time schedules, and the introduction of technology or construction practices under unproven conditions. These challenges can result in a high-risk exposure but also opportunities that bring great rewards.

Project Risk Management Methodology

It is important to perform risk management in a structured manner. Indeed transparent risk management frameworks are becoming statutory requirements for many companies, obliging them to demonstrate how they are managing risks throughout their organizations (ERM) or on an enterprise-wide basis (e. g., the COSO framework in the United States). It is important to ensure that the project risk management methodology is consistent with ERM frameworks. The project risk management process is often broken down into the following five general steps.

- Initiation and focusing: initiate risk management process, including identify project objectives. The initiation should also assign personnel to the main risk management roles such as risk manager.

- Uncertainty Identification: identify risks affecting the project objectives. Assign responsibility for assessing and mitigating each risk.

- Risk analysis: assess for each risk the probability of occurring and the corresponding objective consequences given that the risk occurs. Based on the risk assessment, classify each risk in terms of criticality.

- Action planning: identify risk-mitigating actions so that the most critical risks are mitigated. Assign responsibility and due dates for each action.

- Monitoring and control: review and, if necessary, update risk assessments and corresponding action plans once new and relevant information becomes available.

The “initiation and focusing” step is normally performed once at the start of the project, whereas the four other steps are performed in an iterative manner. The initiation of project risk management in projects has the following set of goals.

- Identify, assess, and control risks that threaten the achievement of the defined project objectives, such as schedule, cost targets, and performance of project delivery. These risk management activities should support the day-to-day management of the project, as well as contribute to efficient decision making at important decision points.

- Develop and implement a framework, processes, and procedures that ensure the initiation and execution of risk management activities throughout the project.

- Adapt the framework, processes, and procedures so that the interaction with other project processes flows in a seamless and logical manner.

The project risk management process should be assisted by a set of tools that supports these processes.

Risk Response Planning

A risk response plan can help maximize the probability and consequences of positive events and minimize the probability and consequences of events adverse to the project objectives. It identifies the risks that might affect the project, determines their effect on the project, and includes responses to each risk. The first step in creating a risk response plan is to identify risks that might affect the project. The project team members should collaborate referring to the project charter, project time line, and budget to identify potential risks. Those involved in the project can often identify risks on the basis of experience. Common sources of risk include the following.

- Technical risks, such as unproven technology.

- Project management risks, such as a poor allocation of time or resources.

- Organizational risks, such as resource conflicts with other activities.

- External risks, such as changing priorities in partner or contractor organizations.

- Construction risks, such as labor shortages or stoppages and weather.

Developing Risk Response Strategies

There is no preparation for mitigating all possible risks, but risks with high probability and high impact are likely to merit immediate action. The effectiveness of planning determines whether risk increases or decreases for the project’s objectives. Several risk response strategies are available.

Avoidance – changing the project plan to eliminate the risk or protect the objectives from its impact. An example of avoidance is using a familiar technology instead of an innovative one.

Transference – shifting the management and consequence of the risk to a third party. Risk transfer almost always involves payment of a premium to the party taking on the risk. An example of transference is using a fixed price contract.

Mitigation – reducing the probability and/or consequences of an adverse risk event to an acceptable threshold. Taking early action is more effective than trying to repair the consequences after it has occurred. An example of mitigation is seeking additional project partners to increase the financial resources of the project.

Acceptance – deciding not to change the project plan to deal with a risk. Passive acceptance requires no action. Active acceptance may include developing contingency plans for action should the risk occur. An example of active acceptance is creating a list of alternative vendors that can be supply materials with little notice.

Because not all risks will be evident at the outset of the project, periodic risk reviews should be scheduled at project team meetings. It is also important not to view risk with a negative mind set. In addition to the downside consequences associated with many risks lie opportunities, which should be identified and strategies developed to exploit them where possible. Risks that do occur should be documented, along with their response strategies in a risk register that assigns responsibilities for specific risks.

Qualitative Project Risk Management

The routine day-to-day identification, assessment, and control of project risks are similar to hazard and operability identification techniques.

The identification of risk consists of collecting and examining information on potential events that may influence the achievement of the project objectives. Each such event is categorized as a risk or an opportunity.

It will be interesting: Key Considerations for Successful Bunkering Facility Development

The identification of these events should involve expertise from all main project competencies to reduce the possibility of important risks being overlooked. These risks will normally be prioritized so that only the most likely and consequential risks will be entered into a formal risk management process. The prioritization of risk should only be performed after thorough assessments and discussions among the project team. New information could mean that risks that have been determined previously as a lower likelihood must be inserted into the risk management process.

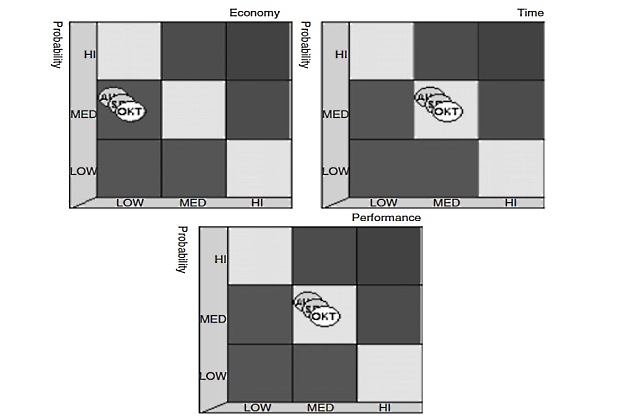

The assessment of each risk or opportunity is made in terms of scores for probability of occurrence and for consequence, given that it occurs, for each project objective. Based on the probability and consequence scores, the criticality of each risk with respect to achieving the project objectives can be assessed. Typically, a classification consisting of several possible probability scores and several possible consequence scores leads to several different classes of criticality, e. g., “critical“, “significant“, and “negligible“. Figure 2 is an example of how risk can be classified in relation to probability, project cost (economy), project effort or duration (time), and project performance.

The control of each risk event is normally based on its risk classification. A risk that is classified as “critical” will normally result in actions being identified in order to reduce the risk classification to either “significant” or “negligible“. The risk reduction can be caused by either preventive measures (reducing the probability that the event will occur) or corrective measures (lessening the consequences of the event) or both.

Quantitative Project Risk Management Assessment

A periodic assessment of the probability of meeting project objectives must be based on quantitative calculation of the aggregated effect of the most important risks on the project objectives. The aggregation must also take into account sequences of scenarios and risk events, as well as the project structures given by the budget, schedule, and operability. Several methodologies exist with supporting tools that can be used for LNG Bunkering Risk Assessment Worksheet Templatesrisk assessment of the total budgets and schedules. The challenge is to apply a methodology and to find a tool that supports this methodology so that the integration of risks in the different domains can take place, their mutual independence can be represented, and their aggregate effect on the project objectives can be assessed. Fortunately, the usage of influence diagrams enables such a methodology and several influence diagram tools exist.

In an influence diagram, each risk is represented as a symbol (or “node“) in a graphic diagram. The diagram represents the structural relationship between the different risks and their aggregate effect on the project objectives. In this manner, influence diagrams are well suited to represent risk scenarios. The mathematics used for assessing the aggregate effect is hidden away “behind” the diagram. In this way the influence diagram also represents a methodology to split a risk management model into two:

- the structural relationship between the various risks and;

- the mathematics of the risk model, such as probabilistic distribution functions for the risks.

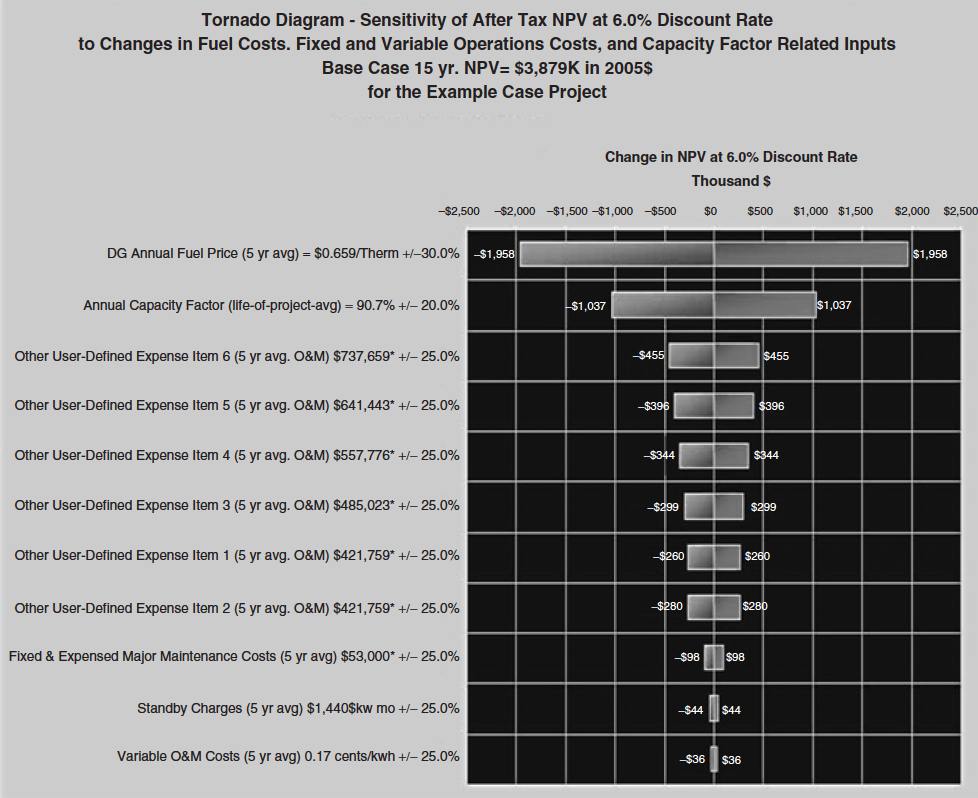

Other quantification methods to identify criticality and rank risks include Monte Carlo simulations and presentation through “tornado diagrams“. Tornado diagrams (an example shown in Figure 3) help identify which input parameters, if they were to change, would have the biggest consequential impacts on the analysis.

They help to establish materiality of potential outcomes and to illustrate how the project will be impacted by changes, in order or significance, of those selected inputs. This provides valuable insight into which parameters might warrant further investigation to determine how changes would impact the objectives.

Risk Process Modeling

The model of the general risk management process is by no means complete. The two most important omissions are as follow.

- No direct representation of the interaction with external organizations and their processes.

- No direct representation of the interaction with other internal processes.

Interaction with other processes should be designed so that the (new) risk management process is integrated as seamlessly as possible into the existing organizations and its already existing other processes (e. g., ERM framework). Any required modifications should be as small as possible.

Read also: Understanding the Fundamentals of US Natural Gas Pricing and Market Volatility

Hence, this risk management process is integrated into the organization by having the already existing weekly management meeting also assessing the weekly risk report. Hence, no new forum for management review of risk is established, only an additional item is added to an existing agenda.

Because different parties in the risk management process have different interest, these interests should correspond to different views into the risk management process. Risk mitigation (and/or exploitation) strategies themselves involve costs to instigate and may lead to secondary risks. It is important to reconcile such costs and secondary risks with the risk management objectives, materiality of the risks being addressed, the project budget, and resources available.

Project Risk Management in Interaction with other Management Processes

It is important to note that risk management has major similarities with other common management processes. Examples of such processes are as follow.

- Management of project changes.

- Management of public permits.

- Management of health, safety, and environmental issues.

- Management of decision gates.

Similarities exist in the identification of items, the assessment of their criticality, the identification of corresponding mitigating actions, and the follow-up of criticality assessment and corresponding mitigation plans. These similarities should be exploited when setting up the risk management processes and establishing the tools for the management of these processes.

The risk management process will remain constant over the different project phases throughout the life cycle of a construction project. The different risk management techniques for assessing day-to-day risks, calculating the ability to meet defined project objectives, and ranking different decision alternatives will also remain the same. In the ranking of different investment opportunities for a Natural Gas Processing and Liquids Recoverygas processing project, a number of issues will in general need to be looked into.

- Revenue.

- Costs (costs of different activities: capital expenditures, operational costs).

- Schedule (of project tasks and completion of milestones).

- Taxes and depreciation.

- Health, safety, and environment (meeting regulations and company requirements).

- Structural reliability (design that meets requirements).

- Onstream factor (design that meets availability requirements).

What will vary, however, over the life cycle is the quality of the available risk related information, the kind of competence that is needed to compile and prioritize this information, and the kind of decisions that are supported by the risk management activities. A believable risk management process must be conducted by personnel with domain knowledge of the project phase in which decisions are to be made.

Because the required competence will vary with the project phase, it is unlikely that the same person can fill the risk manager role throughout the project. Whether one or more risk managers or a team is involved in managing risks it is crucial that analysis, actions, and outcomes are documented in a risk register and widely communicated both within the project team and to project stakeholders.

Other Risk Mitigation Concepts

Other methods of risk mitigation include the following.

- Cost overrun protection. Cost overrun insurance can be purchased. This insurance is used most often for infrastructure such as bridges and islands that may be required to access or locate the facility.

- Regulatory risk. A wide-ranging political or regulatory risks form of insurance is available. This is designed to provide an indemnity in the event that any changes occur to the regulatory requirements or political stance perceived at conception of the project during construction and into commercial operations.

- Revenue stream stabilization. In addition to the historic insurance market places, capital markets are available that enable industry to transfer risks to financial vehicles and through structures different from traditional insurance policies. This market convergence has produced a wide range of creatively devised financial products, which can be applied to uninsurable risks. Hedging the sale prices for specific volumes of products is now widely used, particularly in the initial years of plant production prior to project payback to help reduce project finance risks.

- Blended risk solution. These are integrated risk solutions, which result in a more comprehensive package of protection than the traditional set of policies providing limited but specific coverage addressing different areas of risk.

Quality Assurance

An important part of defining the result and performance of the project is the specification of its quality-related features, which the project must then aim to deliver. Quality assurance has been an issue at the forefront of organizational concerns for decades. The development of quality-conscious construction practices has been identified as being of the utmost importance in gaining and retaining a competitive edge. In the context of a project that aims to deliver a complex result, the quality aspects of that result will need to be planned, designed, aspired, and monitored. Quality assurance is a term used to incorporate the quality policy, quality management, and quality control functions, which combine to assure that the end result will be consistently achieved to the required condition. Its aim is to attain and assure quality through the adoption of a cost-effective quality control system and through external inspections and audits. Quality planning is an integral part of the planning activity. It manifests itself in the descriptions and in the scheduling of quality-related activities. Results of the quality planning activities are reflected in the resource and technical plans at each level of the project. Quality control is concerned with ensuring that the required qualities are built into all of the tasks throughout their development life cycles. Quality control utilizes measurable quality criteria and is exercised via quality reviews, by project reviews, and by the testing of products. Quality assurance requires agreement on the level of quality controls to be adopted, both specifically relating to the project and to the overall organizational policy. It is important that all three interests represented by the project owner are taken into account when deciding the mechanisms to be adopted.

The task descriptions should describe the purpose, form, and components of a task. It should also list, or refer to, the quality criteria applicable to that task. Task descriptions should be created as part of the planning process to shadow the identification of the tasks that are required by the project. Each task description may either apply to a specific item or to all the tasks of a given type. The component tasks of a complex task may be described in separate descriptions, giving rise to a hierarchy of task descriptions for that task.

It will be interesting: LNG Bunkering: Technical and Operational Advisory

Quality criteria should be used to define the characteristics of a task in terms that are quantifiable, and therefore allow it to be measured at various points in its development life cycle, if required. The criteria effectively define quality in the context of the product and are used as a benchmark against which to measure the finished task. Quality criteria should be established by considering what the important characteristics of a result or task are in satisfying the need that it addresses, and they should always be stated objectively. Subjective or descriptive criteria such as “quick response” or “maintainable” are unsatisfactory as they do not permit meaningful measurement.

Quality planning should ensure that all quality-related activities are planned and incorporated into the project schedule. The tasks required to ensure the quality of the delivered result are often overlooked, with the result that the project schedule fails to represent quality-related work.

This can have serious consequences for the quality levels achieved, the overall budget, or both.

Quality control is concerned with ensuring that the required qualities are built into all of the tasks throughout the construction cycle. It defines the method of inspection, in-process inspection, and final inspection to determine if the result has met its quality specification. Quality control utilizes measurable quality criteria and is exercised via change control, quality reviews, project reviews, and by the testing of products.

Reviews should be scheduled prior to key decision dates and important milestones such as shipment of rotating equipment and major equipment. For instance, modifications to a gas turbine are made more easily in the shop prior to shipment rather than in the field after transit. Modifications required that could have been found with shop inspections can cause significant delays.

Many of the top engineering consulting companies operate integrated quality, health, safety, and environmental (QHSE) management systems, which they apply generically across their operations. This is appropriate as it makes clear to their staff that all four of its components are important to ensure successful outcomes and that QHSE all influence each other as well as the budgetary, schedule, and risk issues that drive project decisions. The adage that one should expect what you inspect applies to gas processing project management. Management and technical peer reviews are good practice. Inspection reports monitor not only quality but progress and should be used liberally for best results.

Commissiomimg and Start-up

Commissioning and start-up of a new facility or unit are very important phases of any processing project. These activities can be very expensive from a standpoint of project costs as well as deferral of operating revenues if delays are encountered. For this reason, it is good practice to assign a start-up engineer to plan and coordinate these activities. Operators and maintenance personnel should be hired well before the start-up date and trained on the equipment and process basics.

Familiarity with the particular control system can be accomplished through the use of operator training simulators. These simulators can pay off easily by reducing start-up time. More detailed training on particular aspects of the Safe Start-up and Shut-down of Hydrocarbon Containing Equipment and Processesequipment and process can be given to select individuals. Indeed, many now argue that it is important to have operations and maintenance personnel involved in the design and engineering phase of a project as it is much easier to sort out operational control logistics at the planning stage than later on.

Thorough checkout of the equipment should be conducted by the owner and operator of the facility. Punch lists of all deficiencies should be prepared, reviewed with the constructor, and updated on a daily basis.

Purging of the equipment is quite important for safe start-up. Process gas or an Inert Gas Generatorinert gas, such as nitrogen, can be introduced to remove pockets of oxygen, which could lead to explosions. All high point vents should be opened and checked with a portable oxygen analyzer. These vents should only be closed when oxygen is no longer detected. Excess water and other liquids should also be removed from the system by opening low point drains until purge gas escapes through the drains.

Start-up should be a joint effort among the constructor, operator, and process designers. The constructor should be advised of any deficiencies in the equipment and instrumentation as they are identified by operations and have personnel readily available to resolve the issues. It is not uncommon for construction contracts to include a retention portion of the plant cost that the owner will withhold for a period (e. g., 6 months or 1 year) following start-up to motivate the contractor to deal promptly with any teething problems.

Operate and Evaluate

The final phase of a processing plant project is continuous operation and evaluation of the project results, including plant capability over a finite period of time. Before the plant is turned over to operation, the performance of the plant should be measured. Sometimes this is required by the contractor or process licensor to meet performance guarantees. The capability of each process and equipment should be calculated and become the baseline for operation. At this point you may discard the design capability as this was used only as a basis for sizing equipment. Many times equipment is sized with a contingency giving better than design capability.

Source: AI generated image

Other times, the equipment may not be capable of design. For example, a difference in the actual inlet Chemical Composition and Physical Properties of Liquefied Gasesgas composition from the design basis is a common culprit.

After detailed measurement of the plant’s capabilities and deficiencies, these items should be well documented. The capability information is valuable should the plant require expansion in the future, and deficiencies become the basis for possible debottleneck and retrofit projects.

Project Closeout

In addition to the evaluation activities mentioned in the previous section, project activities should be reviewed. This review should comprise:

- What worked well?

- What did not work well?

- What were the actual costs?

- What was the actual schedule?

- What assumptions need revision?

- What risks materialized and required attention (as documented in the project risk register)?

- Did risk mitigation strategies employed achieve their objectives?

- What are the project economics as constructed and operated?

As a result of this review or project post mortem, the project manager should write a project closeout report that includes the results of the project closeout review and recommendations for future similar projects.

Conclusion

Planning is critical to project success. Detailed, systematic, teamnvolved plans are the foundation for such success. When events cause a change to the plan, project managers must make a new one to reflect the changes so continuous planning is a requirement of project management. Project managers must focus on three dimensions of project success. Project success means completing all project deliverables on time, within budget, and to a level of quality that is acceptable to sponsors and stakeholders.

The project manager must keep the team’s attention focused on achieving these broad goals and the stakeholders aligned to the project objectives.

It is essential that the project team be composed of all key disciplines who create or use the deliverables. The responsibilities of all team members should be clearly defined. Project managers must feel, and transmit to their team members, a sense of urgency. Because projects are endeavours with limited time, money, and other resources available, they must be kept moving toward completion. Because most team members have many other priorities, it is up to the project manager to keep their attention on project deliverables and deadlines. Regular status checks, meetings, and reminders are essential. All project deliverables and all project activities must be visualized and communicated in vivid detail. The project manager and project team must create a picture of the finished deliverables in the minds of everyone involved so that all effort is focused in the same direction. Avoid vague descriptions and make sure everyone understands what the final product will be.

Projects require clear approvals and sign-off by sponsors. Clear approval points, accompanied by formal sign-off by sponsors and key stakeholders, should be demarcation points in the evolution of project deliverables. Anyone who has the power to reject or to demand revision of deliverables after they are complete must be required to examine and approve them as they are being built.

Risk management is an essential responsibility of project management. All risks should be identified and a contingency plan should accompany all critical risks. A gas processing project is not complete until the plant, unit, or equipment is placed in service. An evaluation of the operability should be a deliverable upon completion of the project.

test